Abstract

In the present study, we examined the relationships between adult identity, strength of identity commitments, and their potential determinants: number of adult social roles undertaken and psychosocial maturity. A total of 358 emerging adults aged 18 to 30 participated. Structural equation modelling analyses indicated that psychosocial maturity dimensions served as intervening variables between adult roles on the one hand and adult identity and identity commitments on the other. The results suggest that vocational and familial adult roles can be related to different aspects of psychosocial maturity. Implications and suggestions for future research are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In recent years the transition to adulthood has become an increasing area of research interest. Young people entering adulthood indeed face several challenges connected to various role transitions due to the switch between dependence of childhood and adolescence and the roles typical for adults: completion of education, entrance to the job market, managing a separate household, selecting a partner and starting a family (Hogan and Astone 1986). Most young people also face the task of developing the psychosocial maturity that will help them to function as adult members of society. Greenberger (1984; Greenberger and Steinberg 1986) defined psychosocial maturity as comprising two major domains: autonomy (the ability to independent functioning) and social responsibility (relating well to others, social commitment, contributing to the well-being of society). This psychosocial context entails one of the most important developmental task for young people on the verge of adulthood – the development of one’s own identity understood as establishing a stable self-definition in important domains (Vignoles et al. 2011). Examining the relationships between these different areas of development (i.e., adult roles, psychosocial maturity, and identity) in emerging adulthood (Arnett 2000) was the main goal of this study. We were particularly interested in verifying whether, in line with the life course perspective (Hopwood et al. 2011), engagement in undertaking adulthood roles will turn out to be a predictor of psychosocial maturity and identity of emerging adults, and whether maturity dimensions function in this case as mediators.

Role Transitions in Emerging Adulthood

Currently, young people manifest a marked tendency to postpone full entrance into adulthood defined as undertaking social roles typical of the adulthood period. One of the main reasons for taking up the adult roles later than was the case in the past may be the increasing duration of the education period and the need, thereafter, to spend a few more years developing a career that would ensure relative stability (Arnett 2000; Buhl and Lanz 2007).

A number of studies conducted in the United States (Nelson and Barry 2005), Western Europe (Sirsch et al. 2009), Southern Europe (Galanaki and Leontopoulou 2017), and Central Europe (Oleszkowicz and Misztela 2015; Macek et al. 2007) also suggest that the majority of people at the age of 20-something do not consider themselves as entirely adult. Arnett (2000) called this group of young people, especially those in their twenties, ‘emerging adults’. It has been shown that the majority of emerging adults do not perceive objective, traditional criteria – i.e., fulfilled social roles of adulthood – as crucial for being an adult (Arnett 2000, 2001; Krings et al. 2008). However, the assumption that fulfilling adult roles can in fact be related to their further development has been supported.

Role Transitions and Psychosocial Maturity

Role transitions can be seen as opportunities to develop psychosocial maturity. Early motherhood, for example, is associated with problems in social functioning and in adopting other roles in the professional realm (Rönkä and Pulkkinen 1998), but parenthood in adulthood is more often associated with positive subsequent changes in personality, especially when parents are able to cope with the demands of parenthood (Antonucci and Mikus 1988; Hutteman et al. 2014). Other studies have also demonstrated that people who no longer live with their parents and manage their own households are characterised by more mature levels of personality development, better relationships with their parents, and an increased sense of personal success (Flanagan et al. 1992; Jordyn and Byrd 2003; Seiffge-Krenke 2016). These findings mirrored those for people in long-term relationships (Adamczyk 2017; Årseth et al. 2009).

Role Transitions and Psychosocial Maturity in Identity Development

Studies suggest (e.g. Johnson et al. 2007; Piotrowski 2018) that both crucial areas of development in emerging adulthood, that is, role transitions and psychosocial maturity, may contribute in turn to identity development. Shanahan et al. (2005) found that those who have reached all three transition markers in family life (establishing an independent household, getting married or cohabiting, and having a child) were twice as likely to feel like an adult (a crucial feature of adult identity; Côté 1997), when compared to those who were lacking even one of these transitions. Adamczyk and Luyckx (2015) found a positive relationship between being in a stable intimate relationship and identity commitment (i.e. the degree of personal investment in important domains; Marcia 1966). Also completing formal education and getting a job were found to facilitate identity commitments and hinder exploration of alternatives (Luyckx et al. 2008b), while experiencing difficulties in the job market were more often related to problems with identity commitment formation (Danielsen et al. 2000; De Goede et al. 1999).

These studies suggest that adult role transitions can have a significant impact on identity formation in different domains. This thesis is also supported by the longitudinal study of Benson and Furstenberg (2007), which showed that disengaging from adult roles can decrease one’s sense of adulthood over time. However, as Andrew et al. (2007) have argued, being in an adult role does not automatically confer adult status. It rather acts as a “platform” to adulthood by providing structure for internal changes in the direction of being more responsible, self-reliant, and capable of giving support. Factors mentioned by them are similar to indicators of psychosocial maturity listed by Greenberger (1984) and are also related to the development of identity (Ǻrseth et al., 2009; Kroger 2007; Zimmer-Gembeck and Petherick 2006). Taken together, above mentioned studies suggest close relationships between all areas of development included in the present study.

The Current Study

Research Questions and Hypotheses

The focus of the present study was to examine for the first time the joint influence of adult roles and psychosocial maturity on different spheres of identity (adult identity, i.e. a subjective sense of being an adult as well as on identity commitment). We hypothesized that undertaking adult roles can constitute a contextual factor predicting level of psychosocial maturity, adult identity and personal identity commitments in line with the life-course model of personality development (Hopwood et al. 2011).

We tested a mediational model reflecting relationships between study variables.

Path from Independent Variables to Dependent Variables

Identity can be seen as adaptation to the changing psychosocial context of the developing individual (Baumeister and Muraven 1996; Bosma and Kunnen 2001). In this case, adopting particular adult roles, which is still under the influence of social norms and developmental timetables (Settersten Jr 2004), can change the context of individual’s development and can lead to a transformation in one’s identity. In line with this approach we hypothesized that undertaking adult roles would be positively related to both analysed identity spheres, i.e. adult identity and identity commitments.

According to the life-course perspective on personality development during the transition to adulthood (Hopwood et al. 2011) the increasing maturity observed between adolescence and adulthood occurs, at least partly, as an effect of interactions with the environment and of attempts to adapt to contextual conditions like work activity and romantic relationships. Taking up adult roles (contextual changes) could increase psychosocial maturity (internal changes) by requiring individuals to deal with tasks related to those roles. When individuals finish their education and/or start to work they also change their lifestyle and everyday activities. Vocational activity is usually related to an increase in financial independence, which can be an important step towards autonomous functioning, but which can also be a factor increasing subjective readiness for building a stable, intimate relationship (Caroll et al. 2009). A similar situation could be with familial roles as these could stimulate the development of personal responsibility, the ability to maintain a romantic relationship, or the building of close relationships with children. Those positive changes in maturity following undertaking adult roles can be, subsequently, engaged in the development of identity. Such a direction of change could suggest that psychosocial maturity can be a mediator between undertaking adult roles and changes in identity. In line with this approach:

Path from Independent Variables to Mediators

We hypothesized that undertaking adult roles would be positively related to psychosocial maturity indicators (Andrew et al. 2007; Antonucci and Mikus 1988; Hutteman et al. 2014; Jordyn and Byrd 2003; Seiffge-Krenke 2016).

Path from Mediators to Dependent Variables

We hypothesized that maturity indicators would be positively related to identity formation (Ǻrseth et al., 2009; Kroger 2007; Zimmer-Gembeck and Petherick 2006).

Mediational Hypothesis

We hypothesized that psychosocial maturity would constitute a mediating variable between adopting adult roles on the one hand and identity (i.e. adult identity and personal identity commitment) on the other. In such a case, relationships between adult roles and dependent variables would be reduced (totally or in part) after taking into account psychosocial maturity dimensions as mediators.

Shanahan et al. (2005) argue that a different direction is also possible and that individuals with well-developed personal qualities may select themselves into adult roles that may contribute to their further development. Also, Erikson (1950) stated that intimacy requires a well-developed identity, which suggests that changes in some areas of psychosocial maturity follow identity development. However, the diverse results obtained in this area also suggest mutual, bi-directional relationships between intimacy and identity, with intimacy also serving as a potential precursor of establishing an adult identity (Årseth et al. 2009). The goal of the present research was to verify those different assumptions by considering the main indicators of the transition to adulthood in one study.

Method

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Participants

A total of 358 Poles aged 18 to 30 (Mage = 22.48; SD = 3.59) participated in the study, the majority of whom were women (67.9%, n = 243). All participants were Caucasian. A total of 70% (n = 251) of participants were studying in general secondary schools (Mage = 18.70; SD = .61) or universities (full-time studies; Mage = 23.52; SD = 1.83) at the time of the study. The remainder of the participants had completed formal education. In the non-student group (Mage = 26.42; SD = 1.89), 85% had completed tertiary education and 15% only had a graduation certificate from a secondary school. The participants of the study lived mainly in cities (43% lived in Warsaw, the biggest city in Poland; 1.7 million inhabitants), and only 5% of them lived in the countryside. Most of the participants declared that their financial situation was good: 64.5% (n = 231) said that they could afford most of what they want without having to deny themselves much; 22.6% (n = 81) said that they could afford most things thanks to being frugal; 12.8% (n = 46) gave responses indicating that their income was insufficient to meet some everyday needs.

Measures

Adult Roles

Five adult roles were used in the study: (1) completing formal education, (2) working full-time or part-time, (3) having a close, intimate relationship (marriage or committed relationship), (4) moving out from parents’ household, (5) having children. Fadjukoff et al. (2007) and Shanahan et al. (2005) have suggested that transitions related to family and to working life can be differently related to identity development, hence, should be examined as two different indicators of the transition to adulthood. In line with this suggestion two summary quantitative indexes were constructed to indicate how many of the social roles of adulthood the participants had taken up (Shanahan et al. 2005): (1) vocational life: respondents were assigned a score of 1 every time he or she stated that they had taken up one of the first two adult roles (school completion = 1 and full-time or part-time employment = 1) and a score of 0 if respondents stated that they had not taken up those roles (were studying in a school or university at the time of the research = 0, did not have a job = 0). As a consequence a variable ranging from 0 – no vocational roles, through 1 – one vocational role, to 2 – two vocational roles was constructed; (2) family life: respondents were assigned a score of 1 every time he or she stated that they had taken up one of the three other adult roles (marriage or committed relationship = 1, independent living, i.e. living with peers, partner or alone = 1, parenthood = 1) and a score of 0 if respondents stated that they had not taken up those roles (not married or not in a committed relationship = 0, living with parents = 0, and having no children = 0). As a consequence a variable ranging from 0 – no family roles, to 3 – three family roles was constructed.

Psychosocial Maturity

The study included the Independence and Intimacy Scale (Brzezińska and Piotrowski 2010a), that allows for a rating of participants on two dimensions of psychosocial maturity (Greenberger 1984; Greenberger and Steinberg 1986): (1) a sense of independence (6 items): the level to which an individual takes responsibility for his/her actions, makes independent decisions about his/her life, is independent of others (e.g. I myself decide which actions to engage in), this dimension is similar to the individualistic criteria postulated by Arnett (2000); and (2) intimacy (3 items): the degree to which an individual thinks he/she is ready to engage in and keep a close and intimate relationship with a partner (e.g. I am ready for a long term commitment to one partner). All items were rated on a six point Likert scale from 1 – strongly disagree, to 6 – strongly agree. CFA indicated that the two-factor structure fitted the data well: X2 (23, N = 358) = 79.88, CFI = .94, RMSEA = .08. Cronbach’s alphas were .70 and .81 respectively.

Adult Identity

The Polish version of the Adult Identity Resolution Scale, a part of the Identity Stage Resolution Index (ISRI) by Côté (1997; Piotrowski and Brzezińska 2015) was used to measure adult identity. This scale consists of three items pertaining to a sense of being an adult (e.g. You consider yourself to be an adult), rated on a scale from 1 – not at all true, to 6 – entirely true and comprising a single index. Cronbach’s alpha was .81.

Identity Commitments

Two subscales from the Polish adaptation of the Dimensions of Identity Development Scale (Luyckx et al. 2008a; Brzezińska and Piotrowski 2010b; Piotrowski and Brzezińska 2017) were used to measure two dimensions of identity commitments: (1) commitment making, i.e. the extent to which an individual made choices and commitments important for the development of identity (5 items; e.g. I have decided on the direction I want to follow in my life) and (2) identification with commitment, which defines the level to which an individual identifies with the choices and commitments made (5 items; e.g. My plans for the future match with my true interests and values). The statements were rated on a Likert-type scale from 1 – strongly disagree, to 6 – strongly agree. CFA indicated that the two-factor structure fitted the data well: X2 (33, N = 358) = 110.03, CFI = .95, RMSEA = .08. Cronbach’s alphas for the scales were, respectively, .87 and .76.

Procedure

Data for the study were collected by associates of the first author, mainly psychologists and PhD students of psychology. In secondary schools and among undergraduates, the questionnaires were completed in groups, during classes, and they were undertaken in three different Polish cities. In the case of secondary schools, the researcher would first contact the school headmaster and ask for consent to conduct the study, and then would randomly choose 2–3 senior classes (so that the students were of age, 18 years old in Poland, and could independently decide about their participation) in order to conduct the study. Next, the researcher would present the participants with the aim of the study and ask them whether they wanted to take part in it. In the case of groups of university students, the researcher would ask lecturers whether he/she could conduct the study during the lecturers classes. Three Polish universities were involved in the study and it was undertaken among students who were majoring in psychology, sociology or social work. In these group measures, none of the pupils or undergraduates refused to participate in the study.

In the case of individuals who had already completed education, the study was undertaken individually, either during direct contact or by sending questionnaires via e-mail. In order to reach these individuals, the researchers availed themselves of their private contacts and the snowball method. The participants, and in the case of the secondary schools students their headmasters, were informed about the aim of the research and signed a consent of participation. In the instructions for the participants there was a request to give answers to all the questions included in the questionnaire. It was explained that this would be helpful in further data analysis.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analyses

Descriptive statistics of the variables describing the roles of adulthood are shown in Table 1.

Table 2 shows descriptive statistics and correlations for the study variables. Correlations were in line with expectations and the results of other studies (e.g. Luyckx et al. 2008b). The strengths of the relationships were weak to moderate. The number of adult roles, sense of independence, intimacy, adult identity, as well as commitment making were positively correlated with age. The dimensions of psychosocial maturity, sense of independence and intimacy, were moderately correlated with an adult identity and moderately correlated with one another. Also, the number of vocational and familial adult roles correlated positively. An adult identity correlated positively and significantly with each of the analysed dimensions. For the identity commitment dimensions, those relationships had a similar character although they were weaker, apart from the relationship between commitment making and identification with commitment (strong, positive relationship r = .72).

Mediation Analyses

Structural equation modelling was conducted using AMOS 24.0 software to test the hypothesised mediational models. In order to measure the goodness-of-fit of the tested models, commonly used indicators were used: Chi-square should be as small as possible, and preferably non-significant; comparative fit index (CFI) should be greater than .95; and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) should be lower than .08, and preferably lower than .06 (Hu and Bentler 1999). Because the correlation between commitment making and identification with commitment was strong, those variables were treated as indicators of a more general, latent variable named strength of commitments. In addition, we controlled for biological age and gender in all primary models.

To begin with, the direct effect model was tested (model A). This model assumed a direct effect of the number of fulfilled familial and vocational adult roles on an adult identity and strength of commitments. In this model the number of vocational roles positively predicted an adult identity (β = .16; p < .05) and strength of commitments (β = .16; p < .05), whereas, familial roles were not significantly related to either of the dependent variables. This model fitted the data well: X2 (5) = 10.23; p > .05; CFI = .98; RMSEA = .05. This model explained 12% of the variance in adult identity and only 2% of the variance in strength of commitments. Despite the fact that familial roles did not have a direct effect on an adult identity and strength of commitments it is not precluded that there is a relationship between them. Even in the absence of direct effects indirect effects can still occur (see Hayes 2009 and Zhao et al. 2010) so it is possible that familial roles have an impact on adult identity and identity commitments through maturity dimensions.

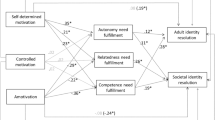

The full-mediation model (B) with maturity dimensions as intervening variables fitted the data very well: X2 (11) = 17.21; p > .05; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .04. The initial direct effect of vocational roles on an adult identity and strength of commitments was fully mediated. There were significant indirect effects (the bootstrapping approach was applied; 1000 bootstrap samples were performed) of vocational roles on an adult identity and strength of commitments through a sense of independence (adult identity: estimate: .09, standard error: .03, 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals from .02 to .15; p < .01; identity commitments: estimate: .03, standard error: .02, 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals from .01 to .07; p < .01) and familial roles on an adult identity through intimacy (estimate: .06, standard error: .02, 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals from .02 to .11; p < .01). The model (B) explained 32% of the variance an adult identity and 5% of the variance in strength of commitments.

Because a different direction of influence has also been suggested, that is identity influencing the development of psychosocial maturity, e.g. intimacy (Beyers and Seiffge-Krenke 2010) and maturity influencing entering adult roles (Shanahan et al. 2005) alternative full mediation models were tested. In the first alternative model (C), an adult identity and strength of commitments mediated between adult roles and psychosocial maturity dimensions. These non-nested models (B and C) were compared using Akaike information criterion (AIC): the lower the AIC value (a difference of more than 10 points suggests a large difference between models; Burnham and Anderson 2004), the better the model fits the data. Based on this criterion, model B was favoured over model C (ΔAIC = 20.64). We also tested a full-mediation model (D) in which the number of adult roles were an intervening variables between psychosocial maturity dimensions and an adult identity and identity commitments. This model, after comparison to the model B, was also rejected (ΔAIC = 92.93).

Finally, the direct paths from the number of fulfilled adult roles to an adult identity and strength of commitments were included in the model B to test a partial mediation model (E). This model also fitted the data well: X2 (7) = 10.62; p > .05; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .04, but the chi-square difference test indicated that, when compared to model B, there was no significant improvement in model fit. The final model (B) is shown in Fig. 1.

Final model of full mediation linking adult roles with adult identity and strength of commitments through psychosocial maturity dimensions of sense of independence and intimacy. For purposes of clarity insignificant paths were not shown. Also paths from control variables were omitted (age correlated significantly with vocational roles, r = .79, with familial roles, r = .58, and with adult identity, r = .24; gender, 0-men, 1-women, correlated significantly only with number of vocational roles (r = .11) and with number of familial roles (r = .14). CM – commitment making, IC – identification with commitment. * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001

Discussion

It was hypothesized that taking up adult roles would be positively related to adult identity and strength of identity commitments through psychosocial maturity (understood here as being independent of others in everyday situations and of being subjectively ready to engage in a stable intimate relationship). In general, those hypothesised assumptions were supported to some extend when the effects of age and gender were controlled for.

Adult Roles and Identity Formation in Emerging Adulthood

The present study divided adulthood roles into two categories: vocational roles (accomplishment of education, activity in the labour market) and familial roles (leaving the family home, being in a committed relationship or marriage, parenthood). Research carried out by Shanahan et al. (2005) and Fadjukoff et al. (2007) showed that both categories of adulthood roles can be differently connected with the identity dimensions. The present study found that a direct relation between adulthood roles and identity was only observed with regard to vocational roles. The more roles belonging to this category that were entered by individuals, the stronger their adult identity and strength of identity commitments were. In the case of familial roles such an association was not observed, which can indicate that the transition from school to work is a process of much greater importance in terms of identity development in emerging adulthood. However, the impact of adult roles was found to operate mainly through the level of psychosocial maturity.

The Role of Psychosocial Maturity in the Link between Adult Roles and Identity Formation

Our results suggest that vocational and familial roles can exert an impact on different aspects of psychosocial maturity. Completion of education and taking a job is mainly connected with a stronger sense of independence, which was found to be the main predictor for an adult identity and the only direct predictor for strength of commitments. One’s situation with regard to familial roles predicted self-assessment in terms of readiness to establish a partnership and long-term relationship, but it had no significant impact on a sense of independence. It could suggest that undertaking vocational roles with their increase in the sense of independence and undertaking familial roles with their increase in the relational abilities are interrelated, but somehow separate processes in emerging adults development (Inguglia et al. 2015). This hypothesis requires further analysis in longitudinal studies.

Some theoretical and empirical-based assumptions state that identity crisis resolution precedes the ability to establish intimate relationships (Beyers & Seiffgke-Krenke, 2010; Erikson 1950) or that they go hand-in-hand throughout the emerging and early adulthood periods (Årseth et al. 2009). However, studies in this area have led to conflicting results, including the idea that there is no relationships between those contructs at all (Sneed et al. 2012). In our study intimacy and identity commitments did not predict one another. Even though there was a weak, positive correlation between intimacy and identification with commitment, it was not revealed in the multivariate model. The mixed results derived from research into the intimacy-identity interplay may be caused by dynamic changes in the role of intimacy and intimate relationships among young people in post-industrial societies. Increasing access to education and diversified career opportunities give emerging adults a greater number of options for defining themselves. That is why a significant number of emerging adults would be more willing to rely on categories such as independence, self-development and self-reliance rather than social connectedness when forming identity commitments. However, intimacy turned out to be an important predictor of an adult identity, which suggests that it is still related to other aspects of self-definition.

Implications for the Emerging Adulthood Theory

The particularly important role of a sense of independence shown in our study is in line with Arnett’s results (2001). He concludes that individualistic criteria are essential for the conception of adulthood shared by people. Our results suggest that also on the level of subjective adulthood and identity commitments, seeing oneself as autonomous and responsible for one’s own actions is crucial in dealing with identity issues in different spheres and domains. Role transitions can be seen, in turn, as important factors contributing to an increase in these personal competences. As claimed by Côté (2000), adulthood is currently influenced by psychosocial development achieved through individual strivings, rather than by classical adulthood markers. The question that could be posed here is: ‘what are the starting points of these individual strivings in emerging and early adulthood’? Our results suggests that an influential source for these strivings can be role transitions. Engaging in them is most often connected to a significant change in functioning (Antonucci and Mikus 1988; Benson and Furstenberg 2007; Kroger 2007) and, as a consequence, young people’s maturity could increase and they could deal with forming their identity more effectively. It is well documented that young people do not see adulthood roles as important elements in their own definition of adulthood (Arnett 2000; Gurba 2008). However, people who engage in these roles are likely to go through a series of psychological changes leading subsequently to both feeling like an adult and strengthening identity commitments. The reason for the discrepancy between the subjective concept of adulthood and the actual determinants of a sense of adulthood may be the lack of appropriate experience that frequently occurs among young people and who in fact avail themselves mainly of personal beliefs about social roles and their meaning. Such a conclusion can be drawn from the study of Aronson (2008), who observed that individuals who have children consider this fact as an important marker of adulthood more frequently than do their peers who do not have children.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

First, the conclusions that have been presented here stem from a single cross-sectional study. Similarly to all other studies on development, the present findings need to be confirmed in longitudinal studies in which reciprocal relationships can be examined. Although we have rejected alternative models, only longitudinal research can give us a more reliable answer to the question about relationships between the analysed constructs. The results of the cross-sectional study presented here do not exclude that other models, which assume different directions of effects, can also be true. Hence, the relationships found in the model should not be treated as proof that the relations between the model’s elements are exactly as shown – they should only be treated as plausible. Second, mainly people who were relatively well-off and well-educated or still studying took part in this study. This is a serious limitation for the generalisation of the results. Third, another limitation is relying only on self-reported data. Fourth, a very general manner of measuring the undertaking of adult roles has been applied in the study. We only checked which of the adult roles were undertaken by the investigated individuals at the time of the study. Unfortunately, neither data pertaining to past engagement in their fruition nor information on the duration of engagement in the present roles were collected. The only exception was checking whether the investigated individuals had ever been divorced (there were no such individuals in the investigated sample). In future studies it would be highly recommended to collect more information on the issues mentioned above, as they may turn out to have a significant influence on the results (Fadjukoff et al. 2007). Finally, the study was conducted in Poland, a country where some adult roles, mostly those connected with family life, are taken up a little earlier than in the majority of West European countries (Mynarska 2010). Thus, the period of psychosocial moratorium may be shorter here and the context in which those processes are submerged may be slightly different. Future research would also profit from a longitudinal study with different indicators of psychosocial maturity and other domains of identity commitments. Readers should note that the lack of a significant relationship between intimacy and identity commitments could also be due to the identity domain assessed in our study. General future plans can be a domain more strongly associated with the transition from school to work and the level of sense of independence than with development of relational abilities.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, our results suggest that both individual and demographic factors could have an important role in forming one’s identity in emerging adulthood. Undertaken adult roles seem to influence psychosocial maturity which, in turn, directly predicts adult identity and identity commitments in emerging adults.

The results that we have obtained suggest that undertaking different roles of the adulthood period can lead to the development of different areas of psychosocial maturity. Our results indicate that there exist two developmental processes in the period of emerging adulthood that result in an increase of sense of adulthood and stabilization of identity. The first of these processes is associated with transitioning from school to labor market, and its effect seems to be, in the first place, an increase in the subjective sense of independence. The second process is related to changes in family life, i.e. leaving home, creating a stable relationship, starting a family. Consecutive steps in this second process lead to an increase in emotional and social competences, enabling the individual to build close relationships in an increasingly more mature manner. These two achievements of emerging adulthood, the conviction about being independent and self-reliant and the conviction about being able and ready to create lasting intimate relationships seem to constitute the basis on which young people who enter adulthood build their overall sense of identity.

References

Adamczyk, K. (2017). Development and validation of a polish-language version of the satisfaction with relationship status scale (ReSta). Current Psychology. Online first. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9585-9.

Adamczyk, K., & Luyckx, K. (2015). An investigation of the linkage between relationship status (single vs. partnered), identity dimensions and self-construals in a sample of polish young adults. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 46, 616–623. https://doi.org/10.1515/ppb-2015-0068.

Andrew, M., Eggerling-Boeck, J., Sandefur, G. D., & Smith, B. (2007). The “inner side” of the transition to adulthood: How young adults see the process of becoming an adult. Advances in Life Course Research, 11, 225–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1040-2608(06)11009-6.

Antonucci, T. C., & Mikus, K. (1988). The power of parenthood: Personality and attitudinal changes during the transition to parenthood. In G. Y. Michaels & W. A. Goldberg (Eds.), The transition to parenthood. Current theory and research (pp. 62–85). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066X.55.5.469.

Arnett, J. J. (2001). Conceptions of the transition to adulthood: Perspectives from adolescence through midlife. Journal of Adult Development, 8, 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026450103225.

Aronson, P. (2008). The markers and meanings of growing up: Contemporary young women’s transition from adolescence to adulthood. Gender & Society, 22(1), 56–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243207311420.

Årseth, A. K., Kroger, J., Martinussen, M., & Marcia, J. E. (2009). Meta-analytic studies of identity status and the relational issues of attachment and intimacy. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 9, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283480802579532.

Baumeister, R. F., & Muraven, M. (1996). Identity as adaptation to social, cultural, and historical context. Journal of Adolescence, 19, 405–416. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.1996.0039.

Benson, J. E., & Furstenberg, F. F. (2007). Entry into adulthood: Are adult role transitions meaningful markers of adult identity? Advances in Life Course Research, 11, 199–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1040-2608(06)11008-4.

Beyers, W., & Seiffge-Krenke, I. (2010). Does identity precede intimacy? Testing Erikson’s theory on romantic development in emerging adults of the 21st century. Journal of Adolescent Research, 25, 387–415. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558410361370.

Bosma, H. A., & Kunnen, E. S. (2001). Determinants and mechanisms in ego identity development: A review and synthesis. Developmental Review, 21, 39–66. https://doi.org/10.1006/drev.2000.0514.

Brzezińska, A. I., & Piotrowski, K. (2010a). Formowanie się tożsamości a poczucie dorosłości i gotowość do tworzenia bliskich związków. [identity formation, sense of adulthood and readiness to establish close relationships]. Czasopismo Psychologiczne, 16, 265–274.

Brzezińska, A. I., & Piotrowski, K. (2010b). Polska adaptacja Skali Wymiarów Rozwoju Tożsamości (DIDS). [Polish adaptation of the Dimensions of Identity Development Scale]. Polskie Forum Psychologiczne, 15, 66–84.

Buhl, H. M., & Lanz, M. (2007). Emerging adulthood in Europe: Common traits and variability across five European countries. Journal of Adolescent Research, 22, 439–443. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558407306345.

Burnham, K. P., & Anderson, D. R. (2004). Multimodel inference: Understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociological Methods Research, 33, 261–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124104268644.

Caroll, J. S., Badger, S., Willoughby, B. J., Nelson, L. J., Madsen, S. D., & Barry, C. M. (2009). Ready or not? Criteria for marriage readiness among emerging adults. Journal of Adolescent Research, 24, 349–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558409334253.

Côté, J. E. (1997). An empirical test of the identity capital model. Journal of Adolescence, 20, 577–597. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.1997.0111.

Côté, J. E. (2000). Arrested adulthood: The changing nature of maturity and identity. New York: New York University Press.

Danielsen, L. M., Lorem, A. E., & Kroger, J. (2000). The impact of social context on the identity-formation process of Norwegian late adolescents. Youth Society, 31, 332–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X00031003004.

De Goede, M., Spruijt, E., Iedema, J., & Meeus, W. (1999). How do vocational and relationship stressors and identity formation affect adolescents mental health. Journal of Adolescent Health, 25, 14–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(98)00136-0.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. New York: Norton.

Fadjukoff, P., Kokko, K., & Pulkkinen, L. (2007). Implications of timing of entering adulthood for identity achievement. Journal of Adolescent Research, 22, 504–530. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558407305420.

Flanagan, C., Schulenberg, J., & Fuligni, A. (1992). Residential setting and parent-adolescent relationships during the college years. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 22, 171–189.

Galanaki, E., & Leontopoulou, S. (2017). Criteria for the transition to adulthood, developmental features of emerging adulthood, and views of the future among greek studying youth. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 13(3), 417–440. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v13i3.1327.

Greenberger, E. (1984). Defining psychosocial maturity in adolescence. Advances in Child Behavioral Analysis and Therapy, 3, 1–37.

Greenberger, E., & Steinberg, L. (1986). When teenagers work: The psychological and social costs of adolescent employment. New York: Basic Books.

Gurba, E. (2008). The attributes of adulthood recognised by adolescents and adults. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 39(3), 129–137. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10059-008-0020-9.

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76, 408–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750903310360.

Hogan, D. P., & Astone, N. M. (1986). The transition to adulthood. Annual Review of Sociology, 12, 109–130. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.12.080186.000545.

Hopwood, C. J., Donnellan, M. B., Blonigen, D. M., Krueger, R. F., McGue, M., Iacono, W. G., & Burt, S. A. (2011). Genetic and environmental influences on personality trait stability and growth during the transition to adulthood: A three-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100, 545–556. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022409.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis. Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Hutteman, R., Hennecke, M., Orth, U., Reitz, A. K., & Specht, J. (2014). Developmental tasks as a framework to study personality development in adulthood and old age. European Journal of Personality, 28, 267–278. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.1959.

Inguglia, C., Ingoglia, S., Liga, F., Coco, A. L., & Cricchio, M. G. L. (2015). Autonomy and relatedness in adolescence and emerging adulthood: Relationships with parental support and psychological distress. Journal of Adult Development, 22, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-014-9196-8.

Johnson, M. K., Berg, J. A., & Sirotzki, T. (2007). Differentiation in self-perceived adulthood: Extending the confluence model of subjective age identity. Social Psychology Quarterly, 70, 243–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/019027250707000304.

Jordyn, M., & Byrd, M. (2003). The relationship between the living arrangements of university students and their identity development. Adolescence, 38, 267–278.

Krings, F., Bangerter, A., Gomez, V., & Grob, A. (2008). Cohort differences in personal goals and life satisfaction in young adulthood: Evidence for historical shifts in developmental tasks. Journal of Adult Development, 15, 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-008-9039-6.

Kroger, J. (2007). Identity development: Adolescence through adulthood (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Luyckx, K., Schwartz, S. J., Berzonsky, M. D., Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Smits, I., & Goossens, L. (2008a). Capturing ruminative exploration: Extending the four-dimensional model of identity formation in late adolescence. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 58–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2007.04.004.

Luyckx, K., Schwartz, S. J., Goossens, L., & Pollock, S. (2008b). Employment, sense of coherence and identity formation: Contextual and psychological processes on the pathway to sense of adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Research, 23, 566–591. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558408322146.

Macek, P., Bejček, J., & Vaníčková, J. (2007). Contemporary Czech emerging adults: Generation growing up in the period of social changes. Journal of Adolescent Research, 22(5), 444–475. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558407305417.

Marcia, J. E. (1966). Development and validation of ego – Identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3, 551–558. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0023281.

Mynarska, M. (2010). Deadline for parenthood: Fertility postponement and age norms in Poland. European Journal of Population, 26, 351–373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-009-9194-x.

Nelson, L. J., & Barry, C. M. (2005). Distinguishing features of emerging adulthood. The role of self-classification as an adult. Journal of Adolescent Research, 20(2), 242–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558404273074.

Oleszkowicz, A., & Misztela, A. (2015). How do young poles perceive their adulthood? Journal of Adolescent Research, 30, 683–709. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558415569727.

Piotrowski, K. (2018). Adaptation of the Utrecht-Management of Identity Commitments Scale (U-MICS) to the measurement of the parental identity domain. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 59, 157–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12416.

Piotrowski, K., & Brzezińska, A. I. (2015). A polish adaptation of James Côté’s identity stage resolution index. Studia Psychologiczne, 53, 33–44. https://doi.org/10.2478/V1067-010-0138-7.

Piotrowski, K. & Brzezińska, A. I. (2017). Skala Wymiarów Rozwoju Tożsamości DIDS: Wersja zrewidowana [The Dimensions of Identity Development Scale: Revised Polish adaptation]. Psychologia Rozwojowa, 22, 89–111. https://doi.org/10.4467/20843879PR.17.024.8070.

Rönkä, A., & Pulkkinen, L. (1998). Work involvement and timing of motherhood in the accumulation of problems in social functioning in young women. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 8, 221–239.

Seiffge-Krenke, I. (2016). Leaving home: Antecedents, consequences, and cultural patterns. In J. J. Arnett (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of emerging adulthood (pp. 177–189). New York: Oxford University Press.

Settersten Jr., R. A. (2004). Age structuring and the rhythm of the life course. In J. T. Mortimer & M. J. Shanahan (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp. 81–98). New York: Springer Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-306-48247-2_4.

Shanahan, M. J., Porfeli, E. J., Mortimer, J. T., & Erickson, L. D. (2005). Subjective age identity and the transition to adulthood: When do adolescents become adults? In R. A. Settersten Jr., F. F. Furstenberg Jr., & R. G. Rumbaut (Eds.), On the frontier of adulthood: Theory, research, and public policy (pp. 225–255). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sirsch, U., Dreher, E., Mayr, E., & Willinger, U. (2009). What does it take to be an adult in Austria? Views of adulthood in Austrian adolescents, emerging adults, and adults. Journal of Adolescent Research, 24, 275–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558408331184.

Sneed, J. R., Whitbourne, S. K., Schwartz, S. J., & Huang, S. (2012). The relationship between identity, intimacy, and midlife well-being: Findings from the Rochester adult longitudinal study. Psychology and Aging, 27, 318–323. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026378.

Vignoles, V., Schwartz, S. J., & Luyckx, K. (2011). Introduction: Toward an integrative view of identity. In S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. L. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 1–30). New York: Springer.

Zhao, X., Lynch Jr., J. G., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37, 197–206. https://doi.org/10.1086/651257.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., & Petherick, J. (2006). Intimacy dating goals and relationship satisfaction during adolescence and emerging adulthood: Identity formation, age and sex as moderators. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 30, 167–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025406063636.

Funding

This study was funded by the European Social Fund grant number WND-POKL-01.03.06–00-041/08.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (the Polish Code of Professional Ethics for the Psychologist; Polish Psychological Association) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

Konrad Piotrowski declares that he has no conflict of interest. Anna I. Brzezińska declares that she has no conflict of interest. Koen Luyckx declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Piotrowski, K., Brzezińska, A.I. & Luyckx, K. Adult roles as predictors of adult identity and identity commitment in Polish emerging adults: Psychosocial maturity as an intervening variable. Curr Psychol 39, 2149–2158 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9903-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9903-x