Abstract

The current investigation examined the association of perceived playfulness in same-sex best friendships with happiness. Study 1 (N = 1009) showed that playfulness was related to and accounted for unique variance in subjective well-being even when controlling for the Big Five dimensions of personality, relationship quality and conflict. Study 2 (N = 277) showed that personal sense of uniqueness mediated the association of playfulness with affect balance. The findings suggest that perceived playfulness is a reliable correlate of individual happiness, and directions for future are provided.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Betcher (1977) developed PQ II to assess perceived playfulness in romantic relationships. While it is not clear how the item pool was created, a factor analysis of 28 items (N = 100) produced six factors, with the sixth factor failing to reveal “any consistent factor” (p. 60). The other five factors were labeled as novelty-spontaneity, control-dominance, asynchrony, rigidity, and in-phase. Importantly, Betcher (1977) argued that the items on PQII were measuring a single construct and he created a total playfulness score. However, he removed four items from this composite that had lower loadings. The other studies using PQII in romantic relationships relied on a composite global playfulness score and none reported a factor analysis (Aune and Wong 2002; Mount 2005; Lutz 1982). As explained in the text, Baxter’s (1992) study is the only one in which PQII was used to assess playfulness in same-sex friendships. This study modified the items assessing sexual play and added two more items. Thus, testing the factor structure of the PQII as used in this study was necessary.

Multiple group CFAs were conducted to test measurement invariance across gender at the configural, metric, and scalar levels. These analyses revealed support for measurement invariance and can be requested from the author.

The association of playfulness with LS, PA and NA were .22, .33, and − .16, respectively (p < .001). Importantly, playfulness accounted for an additional 2% of the variance in LS and PA when taking personality into account. Playfulness did not explain any unique variance in NA above and beyond personality. However, playfulness was positively related to affect balance (PA - NA) (r = .28), and explained and additional 1% of the variance when controlling for personality.

The sample size across the analyses varies due to missing data and outliers. Specifically, 2 and 10 participants did not complete the happiness and friendship measures, respectively. Also, there were a total of 10 and 15 univariate and multivariate outliers in the analyses addressing H3 and H4, respectively. These cases were removed from the final analyses reported.

Gender was positively associated with the original PQII (r = .17, p < .01). Women had higher scores (M = 3.77, SD = .39) when compared to men (M = 3.60, SD = .39), and the difference was significant (t (1006) = 5.35, p < .001, d = .44). The correlation between the original PQII and SWB was .34 (p < .01) in men (n = 183) and .30 (p < .01) in women (n = 815). Among men, PQII explained an additional 2 and 1% of the variance in happiness above and beyond the friendship dimensions (F (1, 179) = 3. 11, p = .08) and personality (F (1, 173) = 2.83, p = .09), respectively. However, these steps were not significant. PQII also did not account for any variance in SWB when personality and friendship were controlled (F (1, 171) = .09, p = .77). Among women, PQII accounted for an additional 2 and 1% of the variance in SWB when controlling for the friendship dimensions (F (1, 800) = 17.02, p < .001) and personality (F (1, 805) = 15.51, p < .001), respectively. Finally, although PQII entered in the last step controlling for the other predictors was significant (F (1, 792) = 4.99, p < .05), the ΔR2 was .003.

The associations of playfulness with positive emotions and negative emotions were .31 and − .15 (p < .01), respectively.

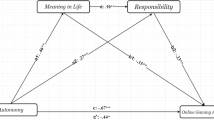

Analyses controlling for gender yielded similar findings (R2 = 20; B = .15, 95% BCa CI = [0.10, 0.22]). Also, the alternative model when controlling for gender was not supported (B = .04, 95% BCa CI = [−0.00, 0.10]).

References

Alberts, J. K. (1990). The use of humor in managing couples’ conflict interactions. In D. D. Cahn (Ed.), Intimates in conflict: A communication perspective (pp. 105–120). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Anglim, J., & Grant, S. (2016). Predicting psychological and subjective well-being from personality: Incremental prediction from 30 facets over the Big 5. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17, 59–80.

Asendorpf, J. B., & Wilpers, S. (1998). Personality effects on social relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1531–1544.

Aune, K. S., & Wong, N. C. (2002). Antecedents and consequences of adult play in romantic relationships. Personal Relationships, 9, 279–286.

Barnett, L. A. (1990). Development benefits of play for children. Journal of Leisure Research, 22, 138–153.

Barnett, L. A. (2007). The nature of playfulness in young adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 949–958.

Barnett, L. A. (2011). Playful people: Fun is in the mind of the beholder. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 31, 169–197.

Baxter, L. (1987). Symbols of relationship identity in relationship cultures. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 4, 261–280.

Baxter, L. A. (1992). Forms and functions of intimate play in personal relationships. Human Communication Research, 18, 336–363.

Berscheid, E. (1983). Emotion. In H. H. Kelley, E. Berscheid, A. Christensen, J. H. Harvey, T. L. Huston, G. Levinger, E. McClintock, L. A. Peplau, & D. R. Peterson (Eds.), Close relationships (pp. 110–168). New York: W. H. Freeman.

Betcher, R. W. (1977). Intimate play and marital adaptation: Regression in the presence of another. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Boston University.

Betcher, R. W. (1981). Intimate play and marital adaptation. Psychiatry, 44, 13–33.

Betcher, R. W. (1987). Intimate play: Creating romance in everyday life. New York: Viking.

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York: Guilford Press.

Busseri, M. A. (2015). Toward a resolution of the tripartite structure of subjective well-being. Journal of Personality, 83, 413–428.

Busseri, M. A., & Sadava, S. W. (2011). A review of the tripartite structure of subjective well-being: Implications for conceptualization, operationalization, analysis, and synthesis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15, 290–314.

Cavanaugh, A.F. (2006). Exploring the role of playfulness, social support and self esteem in coping with the transition to motherhood. Unpublished thesis, University of Maryland, College Park.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1975). Play and intrinsic rewards. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 15, 41–63.

Demir, M., & Davidson, I. (2013). Toward a better understanding of the relationship between friendship and happiness: Perceived responses to capitalization attempts, feelings of mattering, and satisfaction of basic psychological needs in same-sex best friendships as predictors of happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14, 525–550.

Demir, M., & Özdemir, M. (2010). Friendship, need satisfaction and happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 257–277.

Demir, M., & Weitekamp, L. A. (2007). I am so happy ‘cause today I found my friend: Friendship and personality as predictors of happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 8, 181–211.

Demir, M., Özdemir, M., & Weitekamp, L. A. (2007). Looking to happy tomorrow with friends: Best and close friendships as they predict happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 8, 243–271.

Demir, M., Şimşek, Ö. F., & Procsal, A. (2013). I am so happy ‘cause my best friend makes me feel unique: Friendship, personal sense of uniqueness and happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14, 1201–1224.

Demir, M., Orthel-Clark, H., Özdemir, M., & Özdemir, S. B. (2015). Friendship and happiness among young adults. In M. Demir (Ed.), Friendship and happiness: Across the life-span and cultures (pp. 117–136). New York: Springer.

Demir, M., Haynes, A., Orthel-Clark, H., & Özen, A. (2017). Volunteer bias in research on friendship among emerging adults. Emerging Adulthood, 5, 53–68.

Demir, M., Tyra, A., & Özen-Çıplak, A. (2019). Be there for me and I will be there for you: Friendship maintenance mediates the relationship between capitalization and happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9957-8

DeVellis, R. F. (2003). Scale development: Theory and applications (2nd ed.). Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Diener, E., Suh, E., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276–302.

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D. W., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97, 143–156.

Dodgson, M., Gann, D. M., & Phillips, N. (2013). Organizational learning and the technology of foolishness: The case of virtual worlds at IBM. Organization Science, 24, 1358–1376.

Efron, B. (1987). Better bootstrap confidence intervals. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 82, 171–185.

Elkind, D. (2007). The power of play: Learning what comes naturally. Philadelphia: DeCapo Lifelong Books.

Frost, J. L., Wortham, S. C., & Reifel, S. (2012). Play and child development (4th). Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

Furman, W., & Buhrmester, D. (1985). Children’s perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology, 21, 1016–1102.

Gable, S. L., Reis, H. T., Impett, E. A., & Asher, E. R. (2004). What do you do when things go right? The intrapersonal and interpersonal benefits of sharing positive events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 228–245.

Ginsburg, K. R. (2007). The importance of play in promoting healthy child development and maintaining strong parent-child bonds. Pediatrics, 119, 182–191.

Glynn, M. A., & Webster, J. (1992). The adult playfulness scale: An initial assessment. Psychological Reports, 71, 83–103.

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. New York: Harper & Row.

Guitard, P., Ferland, F., & Dutil, E. (2005). Toward a better understanding of playfulness in adults. Occupational Therapy Journal of Research, 25, 9–22.

Harris, K., & Vazire, S. (2016). On friendship development and the big five personality traits. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10, 647–667.

Holmes, R. M. (1999). Kindergarten and college students’ views of play and work at home and school. In S. Reifel (Ed.), Play & culture studies (Vol. 2, pp. 59–72). Stamford: Ablex Publishing.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cuto criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Huizinga, J. (1955). Homo ludens: A study of the play-element in culture. London: Routledge.

Jensen-Campbell, L. A., & Malcolm, K. T. (2007). The importance of conscientiousness in adolescent interpersonal relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 368–383.

John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 102–138). New York: Guilford.

Kennedy, S. C., & Gordon, K. (2017). Effects of integrated play therapy on relationship satisfaction and intimacy within couples counseling: A clinical case study. The Family Journal, 25, 313–321.

Kenny, D. A., & Cook, W. (1999). Partner e ects in relationship research: Conceptual issues, analytic difficulties, and illustrations. Personal Relationships, 6(4), 433–448.

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford.

Koydemir, S., Şimşek, Ö. F., & Demir, M. (2014). Pathways from personality to happiness: Sense of uniqueness as a mediator. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 54, 314–335.

La Guardia, J., Ryan, R. M., Couchman, C. E., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Within-person variation in security of attachment: A self-determination theory perspective on attachment, need fulfillment, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 367–384.

Lauer, J. C., & Lauer, R. H. (2002). The play solution: How to put the fun and excitement back into your relationship. Chicago: Contemporary Books.

Lieberman, N. J. (1977). Playfulness: Its relationship to imagination and creativity. New York: Academic Press.

Lu, L. (1999). Personal or environmental causes of happiness: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Social Psychology, 139, 79–90.

Lutz, G. W. (1982). Play, intimacy and conflict resolution: Interpersonal determinants of marital adaptation. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Northwestern University.

Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005). Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology, 9, 111–131.

MacKinnon, D. P., Fairchild, A. J., & Fritz, M. S. (2007). Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 593–614.

Mallinckrodt, B., Abraham, W. T., Wei, M., & Russell, D. W. (2006). Advances in testing the statistical significance of mediation effects. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 372–378.

Mandler, G. (1975). Mind and emotion. New York: Wiley.

Mandler, G. (1984). Mind and body: Psychology of emotion and stress. New York: Norton.

Marshall, S. (2001). Do I matter? Construct validation of adolescents’ perceived mattering to parents and friends. Journal of Adolescence, 24, 473–490.

Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality. New York: Harper & Row.

Mendelson, M. J., & Aboud, F. E. (1999). Measuring friendship quality in late adolescents and young adults: McGill friendship questionnaires. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 31, 130–132.

Miao, F. F., Koo, M., & Oishi, S. (2013). Subjective well-being. In S. A. David, I. Boniwell, & A. Conley Ayers (Eds.), Oxford handbook of happiness. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Mount, M. K. (2005). Exploring the role of self-disclosure and playfulness in adult attachment relationships. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Maryland, College Parks.

Neff, K. D., Rude, S. S., & Kirkpatrick, K. (2007). An examination of self-compassion in relation to positive psychological functioning and personality traits. Journal of Research in Personality, 41, 139–154.

Playfulness (2006). In Oxford English dictionary online (3rd ed.). Retrieved from http://www.oed.com.libproxy.nau.edu. Accessed Jan 2018.

Powers, W. G., & Glenn, R. G. (1979). Perceptions of friendly insult greetings in interpersonal relationships. Southern Speech Communication Journal, 44, 264–274.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891.

Procsal, A., Demir, M., Doğan, A., Ozen, A., & Sumer, N. (2015). Cross-sex friendship and happiness. In M. Demir (Ed.), Friendship and happiness: Across the life-span and cultures (pp. 171–186). New York: Springer.

Proyer, R. T. (2011). Being playful and smart? The relations of adult playfulness with psychometric and self-estimated intelligence and academic performance. Learning and Individual Differences, 21, 463–467.

Proyer, R. T. (2012a). Development and initial assessment of a short measure for adult playfulness: The SMAP. Personality and Individual Differences, 53, 989–994.

Proyer, R. T. (2012b). Examining playfulness in adults: Testing its correlates with personality, positive psychological functioning, goal aspirations, and multi-methodically assessed ingenuity. Psychological Test and Assessment Modeling, 54, 103–127.

Proyer, R. T. (2013). The well-being of playful adults: Adult playfulness, subjective well-being, physical well-being, and the pursuit of enjoyable activities. European Journal of Humour Research, 1, 84–98.

Proyer, R. T. (2014). To love and play: Testing the association of adult playfulness with the relationship personality and relationship satisfaction. Current Psychology, 33, 501–514.

Proyer, R. T. (2017a). A new structural model for the study of adult playfulness: Assessment and exploration of an understudied individual differences variable. Personality and Individual Differences, 108, 113–122.

Proyer, R. T. (2017b). A multidisciplinary perspective on adult play and playfulness. International Journal of Play, 6, 241–243.

Proyer, R. T., & Jehle, N. (2013). The basic components of adult playfulness and their relation with personality: The hierarchical factor structure of seventeen instruments. Personality and Individual Differences, 55, 811–816.

Ramsey, M. A., & Gentzler, A. L. (2015). An upward spiral: Bidirectional associations between positive affect and positive aspects of close relationships across the life span. Developmental Review, 36, 58–104.

Reis, H. T., O’Keefe, S. D., & Lane, R. D. (2017). Fun is more fun when others are involved. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12, 547–557.

Rogers, C. (1961). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. London, England: Constable.

Schaefer, C., & Greenberg, R. (1997). Measurement of playfulness: A neglected therapist variable. International Journal of Play, 6, 21–31.

Selcuk, E., Gunaydin, G., Ong, A. D., & Almeida, D. M. (2016). Does partner responsiveness predict hedonic and eudaimonic well-being? A 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 78, 311–325.

Selfhout, M., Burk, W., Branje, S., Denissen, J., van Aken, M., & Meeus, W. (2010). Emerging late adolescent friendship networks and big five personality traits: A social network approach. Journal of Personality, 78, 510–538.

Sheldon, K. M., & Hoon, T. H. (2007). The multiple determination of well-being: Independent effects of positive traits, needs, goals, selves, social supports, and cultural context. Journal of Happiness Studies, 8, 565–592.

Shen, S., Chick, G., & Zinn, H. (2014). Validating the adult playfulness trait scale (APTS): An examination of personality, behavior, attitude, and perception in the nomological network of playfulness. American Journal of Play, 6, 345–369.

Şimşek, Ö. F., & Demir, M. (2014). A cross-cultural investigation into the relationships among parental support for basic psychological needs, sense of uniqueness, and happiness. The Journal of Psychology, 148, 387–411.

Şimşek, Ö. F., & Yalınçetin, B. (2010). I feel unique, therefore I am: The development and preliminary validation of the personal sense of uniqueness (PSU) scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 49(6), 576–581.

Steel, P., Schmidt, J., & Shultz, J. (2008). Refining the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 138–161.

Thoemmes, F. (2015). Reversing arrows in mediation models does not distinguish plausible models. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 37, 226–234.

Van Vleet, M., & Feeney, B. C. (2015a). Play behavior and playfulness in adulthood. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 9, 630–643.

Van Vleet, M., & Feeney, B. C. (2015b). Young at heart: A perspective for advancing research on play in adulthood. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10, 639–645.

Vanderbleek, L., Robinson, E. H., Casado-Kehoe, M., & Young, M. E. (2011). The relationship between play and couple satisfaction and stability. The Family Journal, 19, 132–139.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070.

Weiss, R. S. (1974). The provisions of social relationships. In Z. Rubin (Ed.), Doing unto others (pp. 17–26). Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Wilson, R. E., Harris, K., & Vazire, S. (2015). Personality and friendship satisfaction in daily life: Do everyday social interactions account for individual differences in friendship satisfaction? European Journal of Personality, 29, 173–186.

Zhang, J. W., & Howell, R. T. (2011). Do time perspectives predict unique variance in life satisfaction beyond personality traits? Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 1261–1266.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 102 kb)

Appendix

Appendix

Play Questionnaire III-Friendship

For each of the following items please indicate the extent to which the item accurately refers to your perceptions of yourself and your relationship with your same-sex best friend.

1 stands for “definitely not true for me” or “strongly uncharacteristic of the relationship.”

5 stands for “very true for me” or “strongly characteristic of the relationship.”

The middle numbers in the scale stand for intermediate degrees between “very true” and “definitely not true.”

-

1.

I enjoy my best friend’s sense of humor.

-

2.

We have our own unique and creative ways of having fun together.

-

3.

Our play is often stimulating and refreshing.

-

4.

I enjoy being spontaneous with my best friend.

-

5.

I am happiest when we have time to relax and be spontaneous with each other.

-

6.

Sometimes the same humorous thought crosses our minds at the same time.

-

7.

I have fun acting silly with my best friend.

-

8.

I find that our play is often meaningful and rewarding for me.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Demir, M. Perceived playfulness in same-sex friendships and happiness. Curr Psychol 40, 2052–2066 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-0099-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-0099-x