Abstract

Fatalism has been shown to predict several health behaviors, but researchers often find inconsistent results for the same behaviors across studies. This may be partially attributable to the diversity of fatalism measures that have been used in previous studies. A review of the literature revealed 51 different scales, all purported to measure fatalism, but often with heterogeneous content (Esparza 2005). A study done by Esparza (2005) retrieved 29 scales, including the most frequently used scales, and performed an exploratory factor analysis, obtaining as a result five factors: fatalism, helplessness, internality, luck, and divine control. The purpose of this study was to develop a multidimensional fatalism scale based on the previous findings by Esparza (2005). This scale was developed simultaneously in English and Spanish in order to linguistically “decenter” item content. The factor structure was cross-validated and measurement invariance was assessed across language versions. According to the measurement invariance analysis, this test is invariant across English and Spanish in its factor structure, loadings, variances, and covariances. This study results suggest that this scale may be used interchangeably in both English and Spanish.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Fatalism has been a construct of increasing interest in personality and health psychology over the past thirty years. A literature review performed with the PsycINFO database using the term “fatalism” returned 80 published studies from 1985 to 1994, 169 studies from 1995 to 2004, and 334 studies from 2005 to 2014. However, in this extensive body of work, fatalism has been defined and operationalized in many different ways. For example, it has been defined as the belief that outcomes are predetermined by external forces (Ross et al. 1983). Futa et al. (2001) defined it as the acceptance of one’s situation. Fatalism has also been interpreted as a potentially adaptive response to uncontrollable life situations experienced by minorities (Parker and Kleiner 1966). Wheaton (1983) stated that fatalism is a tendency to believe in the efficacy of environmental rather than personal forces in understanding the causes of life outcomes, including both “success” and “failure” outcomes. Scheier and Bridges (1995) focused on the pessimistic aspect of fatalism, claiming that fatalism and pessimism share a common core that involves negative expectations regarding future outcomes. According to these definitions, fatalism has been variously characterized as external locus of control, belief in predetermination, acceptance of reality, or a coping skill. While the term has been usually imbued with negative connotations, there have been at least some definitions that suggest a positive perspective.

Merriam-Webster’s collegiate dictionary (1993) defined fatalism as “the doctrine that all events are subject to fate or inevitable predetermination; the acceptance of all things and events as inevitable; submission to fate” (p. 517). However, there has not been a comprehensive theory of fatalism in the psychology literature. In an initial effort to identify some structure in the field, Acevedo (2005a) reviewed several findings regarding fatalism. He noted that from the sociological perspective, fatalism could be viewed in the context of theories by Durkheim and Marx (Acevedo 2005b) who focused on the over-regulation by social structures, though Acevedo (2005a) also proposed a fatalism theory that included a cognitive factor. He held that fatalism could be the result of social structures, like slavery, but it could also be a cognitive orientation in people.

Acevedo (2005a) distinguished between two types of fatalism: structural and cosmological. Structural fatalism was defined as “a sense of powerlessness that results from a combination of over regulation combined with a lack of exit option into the collective body in which the subject lacks the necessary voice and/or exit option to alter their social position, status, rank, or living conditions” (Acevedo 2005a, p. 75). Structural fatalism could result from feeling powerless due to social structures, like slavery or poverty, which overregulate the lives of people, but structural fatalism could also involve powerlessness due to a perceived lack of self-efficacy, which has been associated with lack of control or mastery (Acevedo 2005a). Cosmological fatalism was defined as “the extent to which a given individual or collective group grants control and decision making authority over life’s outcomes to cosmological or metaphysical powers” (Acevedo 2005a, p. 73). Most frequently, this type of fatalism has involved a voluntary resignation of aspects of one’s life to divine control. Cosmological fatalism has involved “internalization” of one’s fate, while structural fatalism has only involved “acceptance,” rather than internalization of fate. Acevedo emphasized that the types of fatalism he described are different, but not mutually exclusive.

Acevedo’s two types of fatalism parallel, to some extent, work on secondary control, initially outlined by Rothbaum et al. (1982), and more recently reviewed and refined by Morling and Evered (2006). Morling and Evered defined secondary control as “…adjust[ing] some aspect of the self and accept[ing] circumstances as they are” (2006, p. 272). They distinguished between “adjustment” of the self to improve fit with environmental circumstances (a term closely related to Acevedo’s concept of “internalization”), and mere “acceptance” of events, suggesting that both characteristics were necessary to achieve secondary control. Thus, it would seem that Acevedo’s conceptualization of fatalism included secondary control expectations, but focused primarily on acceptance of current and future circumstances, without requiring that adjustment or internalization took place. While Acevedo’s work has begun to outline important theoretical distinctions in the area of fatalism, the area has remained largely undirected by theory, with many researchers using various, and often little-overlapping, measures to assess what they term “fatalism.”

Different Fatalism Scales

A literature search done by Esparza (2005), using the PsychInfo database and the search terms “fatalistic” and “fatalism,” revealed 51 different scales, all explicitly purported by researchers to measure fatalism. Some scales were used quite often, like Rotter’s Internal-External Locus of Control Scale (Rotter 1966), but other scales were constructed and used only for a single study. In addition, some researchers have simply used measures of other constructs as proxies for fatalism. Many researchers have measured fatalism as locus of control (e.g., Joiner et al. 2001; Schedlowski et al. 1995; Wade 1996). Fatalism has been conceptualized as a coping skill in different scales (e.g., Akechi et al. 2001; Classen et al. 1996; Moneyham et al. 1997). Measures of mastery have included fatalism in their subscales (e.g., Green and Rodgers 2002; Neff 1993; Pearlin and Schooler 1978). Other scales and articles have equated fatalism with learned helplessness (Clarke et al. 1982), lack of activism (Chandler 1979; Farris and Glenn 1976), world views (Goodwin et al. 1999; Peck 1981), facets of personality (Wheaton 1983), belief in a just world (Lipkus 1991), perceptions and attitudes about safety (Rudomo and Hale 2003; Williamson et al. 1997), cultural values or constructs (Cuéllar et al. 1995a; b; Sanchez and Garriga 1996), pessimism (Scheier and Bridges 1995), death threat (Moore and Neimeyer 1991), and views and expectations for the future (De Brabander et al. 1999; Somlai et al. 2000).

Recently, the most used fatalism scale has been the Powe fatalism Inventory (Powe 1995). Several cancer studies have used this scale (e.g., Davis et al. 2002; Dettenborn et al. 2004; Farmer et al. 2007; Gonzalez 2007; Gorin 2005; Greiner et al. 2005; Gullatte et al. 2010; Lawsin et al. 2006; Magai et al. 2004; Mayo et al. 2001; Pines 2002; Powe et al. 2006; Russell et al. 2006; Talbert 2007), that has assessed several components of cancer fatalism including belief in divine control and predetermination, pessimism, resignation, and the perceived inevitability of death associated with a cancer diagnosis. All of the items of this scale were related to cancer, for example “I believe if someone gets cancer, it was meant to be”. However, although these constructs have been described by researchers as representing fatalism, it is unclear whether they have had any semantic similarity. In their review of the measurement of fatalism, Abraído-Lanza et al. (2007) mentioned that there has been a lack of established and reliable scales, limited evidence of the validity of existing measures and that the different scales may have tapped different fatalism constructs, suggesting a need to develop complex, valid and reliable fatalism measures.

There have been two new fatalism scales developed recently, but they are specific to health beliefs and diabetes. Shen et al. (2009), developed a scale in which they conceptualized fatalism as a set of health beliefs. Their scale was composed of 20 items divided in three dimensions: predetermination, luck and pessimism. These factors are similar to the factors proposed in the present study but the difference is that Shen et al. (2009) adapted all of their items to health beliefs, for example, “I will get diseases if I am unlucky”. Egede and Ellis (2010) developed a 12-item diabetes fatalism scale with three factors: emotional distress, religious and spiritual coping and perceived self-efficacy. All of their items were related to diabetes, for example, “I get frustrated with having to live with diabetes”.

Analysis of Several Fatalism Scales

In an attempt to bring order to the construct of fatalism and its measures, Esparza (2005) did a literature search and found 51 different scales, all purported to measure fatalism. Twenty-nine of the most commonly used scales were used to analyze the construct. An exploratory factor analysis was performed on 239 items that were obtained from the 29 fatalism scales. Items loaded onto five main factors. The content of the first factor was labeled “fatalism” because it most clearly reflected the belief that events are fixed in advance. Examples of items that loaded on this factor were “When something bad happens, I accept it as unavoidable,” and “If bad things happen, it is because they were meant to be.” This factor appeared to define the core of the fatalism construct and related more closely than the others to the definition given by Merriam-Webster’s collegiate dictionary (1993)—“a doctrine that events are fixed in advance so that human beings are powerless to change them” (p. 517).

Items from the second factor were related to perceptions of helplessness and pessimism, and thus the factor was labeled helplessness. Examples of items that loaded on this factor were “Every time I try to get ahead, something or somebody stops me,” and “I often feel helpless in dealing with the problems of life.” Items that loaded onto the third factor were all related to expectancies of internal control over important life events. They were all reverse coded in an effort to measure fatalism. Examples of items that loaded on this factor were “When I get what I want, it's usually because I worked hard for it,” and “What happens to me in the future mostly depends on me.” Almost all items that loaded on the fourth factor included the words “luck” or “fortune.” Examples of items that loaded on the fourth factor were “Luck plays a big part in determining how soon I will recover from an illness,” and “Many of the unhappy things in people's lives are partly due to bad luck.” All of the items that loaded on the fifth factor included the word “God.” Examples of items that loaded on this factor were “Whether or not my health improves is up to God,” and “Everything that happens is part of God's plan.” This factor, dubbed “divine control,” was highly internally consistent. Finally, there were 108 items that did not load on any of the five factors, for example “Whenever I don’t feel well, I should consult a medically trained professional” and “I’ve had a good life, what’s left is a bonus.”

Items from these scales did not measure a single fatalism construct but rather five different, but correlated, factors. The lowest correlations were between the factors of helplessness and divine control (r = 0.05), the factors of externality and divine control (r = 0.10), the factors of luck and divine control (r = 0.20), and the factors of ineluctable destiny and externality (r = 0.27). The highest correlation was between the factors of ineluctable destiny and helplessness (r = 0.48). The divine control factor had small correlations with most of the other scales. In addition, many items did not load on the five factors. The findings suggested a need to elaborate a fatalism instrument that brings unity in its measure. This type of scale would help us advance the understanding of the construct of fatalism and its relationships to other variables.

The Present Study

The present study was undertaken to develop a new multidimensional measure of fatalism and related constructs informed by Esparza (2005). In the development of new instruments there is a risk of ethnocentric bias that may threaten cross-cultural validity (Tanzer 2005). The term “centering” refers to the origination of a scale in one language and culture, embedding it in that linguistic and cultural context to an extent that it is difficult or inappropriate to transfer the scale to a new context. Tanzer (2005) pleads for simultaneous development of scales to maximize cultural and linguistic “decentering,” in an attempt to reduce biases across cultures from the beginning. The process of simultaneous development involves constructing items for a scale in two languages at the same time. Because of the likelihood that a new fatalism measure would be used in cross-cultural and multilingual research, a simultaneous development approach was used in the current study, and measurement invariance analyses were employed to assess the equivalence of the two versions of the instrument.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 791 participants recruited from Introduction to Psychology classes at the University of Texas at El Paso. Participants were 64.6 % females and 35.4 % males, with a mean age of 20.34 (σ = 4.65). Most of the sample was Hispanic (86.2 %), with non-Hispanic White participants making up 7.5 % of the sample. In regard to marital status, 90.5 % were single and 7 % were married or living with a romantic partner. The mean socioeconomic status for the head of household, measured by the two-factor Hollingshead socioeconomic status index, was 42.58, which reflects a social stratum comprising medium business, minor professional, and technical workers (Hollingshead 1965). The sample was divided randomly into two subsamples: One of the subsamples was used for the exploratory factor analysis (n = 400) and the second subsample for the confirmatory factor analysis (n = 391). There were 513 participants who answered the fatalism items in English during the first administration and 278 in Spanish.

In discussing power analyses for factor analysis, MacCallum et al. (1999) note that sample size should be related to item communalities, number of factors, and number of items per factor. MacCallum et al. (1999) suggest that “if results show a relatively small number of factors and moderate to high communalities, then the investigator can be confident that obtained factors represent a close match to population factors, even with moderate to small sample sizes” (p. 97). In this study, communalities for the exploratory factor analysis ranged from 0.63 to 0.90 and the items were written to load on the expected factors.

Materials

Demographics

Participants were asked about their age, gender, ethnicity, and proficiency in English and Spanish.

Two-Factor Hollingshead Socioeconomic Status Index

This index is typically computed from occupation and education of the participant (Hollingshead 1965). However, because participants in this study were students, they were asked to provide the information on the current head of their household. Hollingshead (1975) reported that the two factors accounted for 98 % of the variance in sociologist’s ratings of social status, suggesting that the index has adequate construct and content validity. Hollingshead ratings were completed by a rater (the first author) who was trained to an inter-rater reliability correlation of r = 0.98. Scores ranged from 11 to 77, with smaller scores corresponding to higher socioeconomic status.

Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans II (ARSMA-II)

This instrument measures the construct of acculturation to the Mexican and the Anglo cultures. The ARSMA-II contains two independent scales that measure Mexican Orientation and Anglo Orientation separately. The Mexican Orientation Subscale (MOS) is composed of 17 items and the Anglo Orientation Subscale (AOS) is composed of 13 items that are answered on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Almost Always/Extremely Often” to “Not at all.” Higher scores on the subscales mean greater identification with the culture each is measuring. The MOS has an internal consistency score of α = 0.88 and the AOS has an internal consistency of α = 0.83 (Cuéllar et al. 1995a; b).

Attributional Style Questionnaire (ASQ)

The Attributional Style Questionnaire was developed to assess dispositional attributions hypothesized to lead to learned helplessness and depressed mood (Peterson et al. 1982). The ASQ measures three dimensions: Internality, Stability, and Globality. For purposes of this study, only the Internality dimension was used to analyze its relationship with the internality factor of our fatalism scale. Higher scores are related to more internal locus. Although widely used by researchers in the past, the internality scale has the lowest internal reliability of the three dimensions, with a Cronbach alpha of 0.50 for positive events and 0.46 for negative events (Peterson et al. 1982).

Belief in Good Luck Scale (BIGL)

This measure reflects a belief in a stable and personal good fortune, distinct from the concepts of optimism, self-esteem, or locus of control (Darke and Freedman 1997). The instrument is composed of 12 items with a five-point Likert type response scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree” (1) to “Strongly Agree” (5). Higher scores mean participants believe more strongly that life has been good to them—that they have good luck. The internal consistency of this scale is α = 0.85, and the 1–2 month test-retest reliability is r = 0.63 (Darke and Freedman 1997).

Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

This is a self-report measure from the Prime-MD (Spitzer et al. 1994) that consists of nine items assessing self-report depressive symptoms from the DSM-IV from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). According to the authors, PHQ-9 scores of 5, 10, 15, and 20 represented mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe depression, respectively. The reported internal reliability (alpha) of the PHQ-9 has ranged from 0.86 to 0.89 (Kroenke et al. 2001).

Life Orientation Test- Revised (LOT-R)

This instrument measures optimism for the future. This is a six-item measure with four filler items. Higher values imply optimism. The answer format is a five-point Likert type scale ranging from “I agree a lot” (1), to “I disagree a lot” (5). Its Cronbach alpha is 0.82 (Scheier and Carver 1992) and its 28-month test-retest reliability is r = 0.79 (Scheier et al. 1994).

Duke Religion Index (DRI)

This is a five-item instrument of religiosity with internal consistency of α = 0.91 (Storch et al. 2004). The scale was developed to assess beliefs, practices, and personal devotions.

Design and Procedure

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects at UTEP. Participants rendered informed consent, and group seating and data collection efforts were structured to maximize confidentiality and anonymity of responses. For the first phase, items were generated in English and Spanish using the simultaneous development approach proposed by Tanzer (2005). This procedure involves a “committee approach” which includes bilingual people with the experience of both cultures and with experience in mainstream psychology, psychometrics, test construction techniques, cultural psychology, cross-cultural psychology, and linguistics (Tanzer 2005). When items are written in two languages simultaneously, idioms specific to one language or culture are generally avoided, leading to decentering of the measure and easier translation to other linguistic and cultural contexts.

For the second phase of the study, an empirical item selection approach was applied. Exploratory factor analysis was used to test the hypothesized factor structure and obtain the items with the highest loadings on each of the factors. Once items were selected, the factor structure was cross-validated through a confirmatory factor analysis with a second sample. The confirmatory factor analysis assessed model fit of the new multidimensional fatalism measure.

The third step was to analyze measurement invariance and structural invariance across the English and Spanish versions of the fatalism measure (Byrne et al. 1989). Measurement invariance included invariance of factor loadings, regression intercepts, and error/uniqueness variances, while structural invariances included invariance of factor variance-covariance structures and factor means (Byrne et al. 1989).

Convergent and discriminant validities were assessed in the fourth phase. From literature review, a list of brief and well-established measures conceptually associated with the hypothesized factors was obtained. Pessimism (the LOT-R) and depression (the PHQ-9) were used to assess the convergent validity of the helplessness factor (Anderson 1990; Burns and Seligman 1991; Luten et al. 1997: Peterson and Vaidya 2001). The internal attribution subscale of the ASQ was used to assess convergent validity of the internality factor The BIGL was selected as the most conceptually similar to the luck factor. The divine control factor was paired with the Duke Religion Index. The fatalism factor has, in past research, been the first and strongest factor from items used in other fatalism scales; it is the factor that best reflects the core concept of fatalism as defined by the Merriam-Webster’s collegiate dictionary (1993). Since no existing measure assesses that single factor, it was decided to only assess discriminant validity of this factor.

Results

Item Generation and Selection

Items were elaborated by two bilingual/bicultural content experts in both English and Spanish simultaneously for each factor of the five factors identified in the first phase. Items were required to have a similar meaning in English and Spanish using a comparable vocabulary and avoiding idioms. Each expert created a list of 20 items per factor based on the factor definitions and sample items from the study done by Esparza (2005). After eliminating identical items from this original list of 40 items per factor, the fatalism factor had 31 items, the helplessness factor had 36 items, the internality factor had 30 items, the luck factor had 37 items, and the divine control factor had 37 items. To further reduce the number of items (and the required sample size for factor analysis) the authors chose the best 18 items per factor, based on face validity. Items that addressed the construct in a broad manner were kept (e.g., If bad things happen to me in life, it is because of God's will), and items with more topic- specific content were rejected (e.g., It doesn't matter who is in political power, since it's God's will what happens in a country). The pool of items was then revised in both languages by a bilingual group of graduate students and undergraduate students in psychology. A final revision of the translations was done by a certified translator.

The readability of the scales in English and Spanish was analyzed. For the English form, the Flesh-Kincaid Grade Level (FKGL) value was 5.67, indicating a reading level of 5th grade. The Flesh Reading Ease (FRE) value was 79.18, indicating a reading level of a 7th grade. For the Spanish form, the Huerta Reading Ease (HRE) index was 91.73, indicating a reading level of 5th grade.

Two different versions (Form A and Form B) of the fatalism questionnaire were generated, with items ordered randomly to control for order effects. Order effects were assessed following the procedure by Panter et al. (1992). Invariance was assessed across Form A and Form B, and no order effects were found. The sample size for Form A was 398 and for Form B it was 393.

Exploratory Factor Analysis and Cross-Validation—Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Missing Data

There were missing data on the fatalism measures. Out of the 71,190 data values from the fatalism measures, 134 (0.19 %) were missing. Since all participants answered most or all of the items, and since the percentage of missing data was low, it was decided to impute missing data. Data imputation was performed using the expectation maximization algorithm (Dempster et al. 1977) with the computer program NORM 2.03 (Schafer 2000).

Exploratory Factor Analysis

Our initial group of 862 participants was randomly divided into two samples. The exploratory factor analysis was performed with all 90 items and with a sample size of 400. Five factors were extracted using generalized least squares with a Promax rotation. Eigenvalues for the five factors ranged from 16.21 for the divine control factor to 2.22 for the fatalism factor. The percent of the variance explained by each factor ranged from 18.01 % for the divine control factor to 2.47 % for the fatalism factor. Items loaded on the expected factors. Based on the factor loadings, six items per factor were selected for scale inclusion. The selected items were those with the highest loadings that did not have a higher loading on other factors (Table 1). Loadings for the selected items ranged from 0.50 to 0.88 and the communalities of the selected items ranged from 0.63 to 0.90.

Normality of Data

For the confirmatory factor analysis, normality for the data was assessed by analyzing the ratio of the skewness statistic and the standard error of the skewness per item (Curran et al. 1996; West et al. 1995). There were 23 skewed items, so since our data were not normally distributed, the diagonally weighted least-squares (DWLS) method was used to analyze the models for this study. The DWLS method outperforms the weighted least-squares (WLS) when sample sizes are limited (Flora and Curran 2004).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

A sample of 391 participants was used to cross-validate the factor structure of the fatalism measure. The confirmatory factor analysis included five factors and each factor included six items, for a total of 30 items (Table 2). In order to calculate the model, the variance of the item with the highest loading per factor had to be constrained to one. Model fit was evaluated with the following results: The SBχ2 with 395° freedom was equal to 647.41 (p < 0.01). The rest of the values were: NNFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.04, CFI = 0.97, NFI = 0.94, GFI = 0.96, and SRMR = 0.05. Using Hu and Bentler (1999) criteria, all indices indicate a good model fit except for the SBχ2. Loadings for this model ranged from 0.37 to 0.87 (Table 3).

The factors were intercorrelated (see Table 4). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients (α) indicating internal consistency of the scales across samples were acceptable for all subscales: fatalism (α = 0.76), helplessness (α = 0.76), internality (α = 0.80), luck (α = 0.82), divine control (α = 0.92). Some shrinkage was observed upon cross-validation, as expected.

Test-Retest Reliability

One week test-retest reliability was assessed by correlating factors scores derived from the first session with the factor scores from the second session. Five hundred seventy-eight participants completed the fatalism form for Time 2. The Pearson product–moment correlation for the fatalism factor was r = 0.71, for helplessness it was r = 0.73, for internality it was r = 0.63, for luck it was r = 0.77, and for divine control it was r = 0.87.

Measurement Invariance

Because the χ 2 and the Δχ2 indices are sensitive to sample size and to non-normal data (Cheung and Rensvold 2002; Little 1997; Marsh et al. 1997), we used the difference in the comparative fit index (ΔCFI) as an index to assess invariance between nested models and the baseline model. A ΔCFI of less than or equal to 0.01 suggests similar model fit (Byrne et al. 2007; Cheung and Rensvold 2002).

Since our confirmatory factor analysis indicated a good model fit, measurement invariance was assessed across English and Spanish. A confirmatory factor analysis was done for each of the samples. Both the English and Spanish models had good fit indices (Table 5). Thus, configural invariance was analyzed. The configural invariance model is the baseline model to which the rest of the nested models were compared using the ΔCFI value (Byrne et al. 2007; Cheung and Rensvold 2002). The configural invariance model showed good fit (Table 5), so loadings were constrained to equality across samples (metric invariance). The model fit well and the ΔCFI value was less than 0.01 (Table 5). Next, item intercepts were constrained to equality (scalar invariance), and good fit was once again observed (Table 5). Finally, the item errors were constrained to equality (strict factorial invariance). The ΔCFI value was less than 0.01 and all of the fit indices (Table 5) were in the range recommended by Hu and Bentler (1999). To test structural invariance, factor variances and covariances were constrained to equality across language. Again, the model was a good fit and the ΔCFI value was less than 0.01 (Table 5).

Since the scale had strict configural invariance and structural invariance in its factor variances and covariances, it was possible to calculate differences in factor means across the English and Spanish samples. Following Byrne (1998), the factor means of the English sample were permitted to vary and the factor means of the Spanish sample were fixed at zero. Item intercepts in the Spanish sample were also held invariant (Byrne 1998). The analysis indicated significant differences in the fatalism factor, the internality factor, the luck factor, and the divine control factor and the difference estimates were 0.20, −0.14, 0.06, and 0.08, respectively. Even though the differences are significant, each difference is less than a point of the scale.

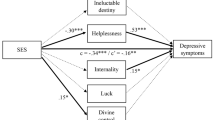

Convergent and Discriminant Validity

To assess convergent and discriminant validity, the fatalism factors were correlated with the selected criterion measures. Table 6 shows the correlation between the fatalism factors and measures of optimism, internality, belief in good luck, depression, and religiosity. As predicted, the helplessness factor had its highest correlations with optimism and with depression, the luck factor had its highest correlation with belief in good luck, the divine control factor had the highest correlation with religiosity, and the internality factor had its highest correlation with the internality dimension of the ASQ. The correlations with the ASQ were low, probably due in part to the low internal reliability of the criterion measure in this sample (α = 0.36). Discriminant validity was evidenced by lower correlations between the scales and criterion variables with which associations were not hypothesized. The fatalism factor was not expected to correlate highly with any of these measures, though it correlated significantly with all of them, most highly with depression.

Finally, the associations between socioeconomic status, acculturation, and the fatalism factors were tested. Socioeconomic status did significantly correlate with the fatalism factors. The only factor to be correlated with acculturation was internality (r = −0.13, p < 0.01 with the Mexican Orientation Scale and r = 0.12, p < 0.01 with the Anglo Orientation Scale).

Discussion

The factor structure of the study done by Esparza (2005) was well-replicated in our study with items written specifically for that purpose. Although some items had shared loadings, especially those on the fatalism factor, there were enough items per factor to choose those that would provide distinct measure of the constructs in question. Six items were selected for each subscale to balance concision with internal reliability. The confirmatory factor analysis cross-validated the structure of the fatalism measure in an independent sample, and there was relatively little shrinkage in internal consistency upon cross-validation. One-week test-retest reliabilities were acceptable, except for the internality factor, which had an r = 0.63.

The multidimensional fatalism measure developed has the potential of bringing unity in the measurement of fatalism and clarity in the findings. The developed scale is a reliable and valid measure with good psychometric properties that can be used interchangeably in English or in Spanish.

It seems clear that the first factor encompasses the core of the fatalism construct as defined in the modern lexicon. It reflects a tendency to view all events (whether positive or negative) as fixed in advance and inevitable, while not necessarily anticipating a particular outcome.

The second factor to emerge, labeled “helplessness,” is similar in content to what Acevedo (2005a) refers to as structural fatalism. It reflects a pervasive pessimistic outlook and is strongly linked to depression. However, in psychology this construct has its own rich literature separate from work on fatalism (e.g., Seligman 1975) and has been most frequently studied in the context of psychopathology, rather than normal personality. It may be best to distinguish it from fatalism in future research.

The divine control factor is similar to the concept of cosmological fatalism that Acevedo proposes, and also reflects secondary control expectations, as defined by Morling and Evered (2006). However, this factor was the least well correlated with the others, and virtually uncorrelated with helplessness and internality. Content of the items, while reflecting a strong belief in divine intervention, did not generally make reference to predetermination of events. The strong internal consistency of the factor suggests that belief in divine control is an important variable in its own right, and the present results suggest that it should be measured separately from fatalism. Indeed, work such as that by Wallston et al. (1999) has advanced the study of divine control beliefs.

Even further removed from the core construct of fatalism are the factors of luck and internality. The existing conceptualizations of luck in the psychological literature have ranged from that of a random and unpredictable variable (e.g., Weiner 1974) to a relatively stable individual difference (e.g., Darke and Freedman 1997; Wagenaar and Keren 1988). Items loading on the current luck factor reflect these two extremes, from “To a great extent my life is controlled by accidental happenings,” to “Some people are just born lucky.” However, again this literature has developed independently of work on fatalism (e.g., Pritchard and Smith 2004) and may be best identified as a separate domain.

As for internality, it is perhaps surprising that this factor emerged distinctly from the other four factors and had the lowest correlation with the core fatalism factor. Multiple researchers in the past have assumed that low internal locus of control is indicative of high fatalism (Cole et al. 1978; De Brabander, et al. 1999; Joiner, et al. 2001). However, the present results suggest that the two concepts do not necessarily define opposite ends of a single dimension.

Of the five factors proposed by Esparza (2005), the first and largest factor is the only one that is not already well established under a different name in the “nomological net” of psychological constructs, with a corresponding supportive literature. We believe that this reflects the fact that this factor best defines the concept of “fatalism,” and should be the primary target of future fatalism research. It is essential that researchers define more clearly the nature of the variable they wish to study when conducting work on fatalism. Indeed, it is possible that diversity in previous measures of fatalism might help explain the inconsistency across existing studies of the construct.

This is the first report of measurement invariance data from an instrument developed simultaneously in two languages. Following the guidelines by Tanzer (2005), simultaneous development in English and Spanish resulted in a decentered instrument that is invariant across language in its factor structure, loadings, item intercepts, item uniqueness, and factor variances and covariances. Indeed, the highly consistent results of the language comparisons are atypical in the measurement invariance literature, lending support to the simultaneous development approach.

Once measurement invariance was established and latent mean differences were evaluated, there were significant differences between the English and Spanish samples on all of the factors, except for helplessness. However, although the differences were statistically significant, none of them exceeded one point on a scale from 6 to 30. The greatest difference (on the fatalism factor) was two-tenths of one point, there does not appear to be a practically significant effect of language on latent means.

The convergent and discriminant analyses shows how the five related but distinct factors behave differently with other constructs. Each factor, except for the internality factor, correlated strongly and uniquely with its designated construct in the hypothesized manner. However, other correlations varied not only in magnitude, but also in direction, depending on the factor under consideration. For example, while religiosity correlated positively with divine control and fatalism, it was negatively associated with the luck factor. Past studies in which these factors have been conflated in a single fatalism measure have been unable to detect such subtleties.

Although the majority of the current sample was Hispanic (86.2 %) this may not have greatly impacted the factor structure identified. Cole et al. (1978), compared fatalistic attitudes of Mexicans and Chicanos with participants from the US, Ireland, and West Germany, and found no difference in fatalism indicators. Future directions include analyzing the factor structure of the fatalism measure in other populations that are not college students, with other ethnic groups, with different age groups, in different parts of the country or other countries.

One limitation of this study is that there was no control for Type 1 error since there were numerous analyses done with the data. While explicit directional hypotheses were stated in most cases, there remains the possibility that some bivariate associations in the current study may have been exaggerated due to unique sample characteristics. Also, due to concern about overburdening student participants, no health measures could be included in this study to analyze their relationships with the fatalism factors. For future studies, another internality instrument should be used to compare it to the internality factor of the scale. Even though the highest correlation of the internality factor was with the ASQ, the correlation was not strong (r = 0.24) since the internality dimension of the ASQ had a poor internal consistency (α = 0.36).

The present study contributes to the clarification of the constructs that have been assessed in past research on fatalism. The new measure of fatalism and related constructs may further advance understanding in the domain. We propose to use the fatalism factor of this measure to analyze the relationship between fatalism and other behaviors. The other four factors (helplessness, internality, luck, and divine control), even though some have used to measure fatalism, they should be analyzed separately and not to be confused with fatalism. For example, a study reports a significant correlation of r = 0.19 between fatalism and a cardio-metabolic dysfunction score (Espinosa and Gallo 2013). They use a fatalism measure from Cuéllar et al. (1995a)b that include the following items: “People can’t really do much to change what happens in life. You just have to accept things”, “It’s more important to enjoy life now than to plan for the future”, “I live for today because I don’t know what will happen in the future”, “I don’t plan ahead because most things in life are a matter of luck”. According to our findings, the only item that reflects the construct of fatalism is the first one, but in the Cuéllar fatalism measure all of these items are included in their fatalism factor. If the same analysis was done using our scale, then the relationship between fatalism and cardio-metabolic dysfunction would be more precise. Also the other four factors of our scale could be correlated to analyze those relationships, which are different from fatalism.

This measure may be used to test theoretical associations between the proposed constructs and important health behaviors. There are several studies in which fatalism has been related to health behaviors. Some examples include cardio-metabolic dysfunction (Espinosa and Gallo 2013), cancer screening (Espinosa and Gallo 2011), HIV and AIDS prevention (Gwandure and Mayekiso 2012), protective sun behaviors (Coups et al. 2014), and adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy (Vyas et al. 2014). We expect to have more exact results using this scale in health related behavior studies since it has a factor that is purported to measure specifically the fatalism factor without having items that represent other constructs like luck, helplessness, divine control or internality.

References

Abraído-Lanza, A. F., Viladrich, A., Flórez, K. R., Céspedes, A., Aguirre, A. N., & De La Cruz, A. A. (2007). Commentary: Fatalismo reconsidered: A cautionary note for health-related research and practice with Latino populations. Ethnicity & Disease, 17(1), 153–158. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3617551/.

Acevedo, G.A. (2005a). The structure and function of fatalism as a social belief system: A cross-national study of collective consciousness (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 3168847).

Acevedo, G. A. (2005b). Turning anomie on its head: Fatalism as Durkheim’s concealed and multidimensional alienation theory. Sociological Theory, 23(1), 75–85. doi:10.1111/j.0735-2751.2005.00243.x.

Akechi, T., Okuyama, T., Imoto, S., Yamawaki, S., & Uchitomi, Y. (2001). Biomedical and psychosocial determinants of psychiatric morbidity among postoperative ambulatory breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 65(3), 195–202. doi:10.1023/A:1010661530585.

Anderson, S. M. (1990). The inevitability of future suffering: The role of depressive predictive certainty in depression. Social Cognition, 8(2), 203–228. doi:10.1521/soco.1990.8.2.203.

Burns, M. O., & Seligman, M. E. P. (1991). Explanatory style, helplessness, and depression. In C. R. Snyder, D. R. Forsyth, & R. Donelson (Eds.), Handbook of social and clinical psychology: The health perspective. Elmsford: Pergamon Press.

Byrne, B. M. (1998). Structural equation modeling, with LISREL, PRELIS, and SIMPLIS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Byrne, B. M., Shavelson, R. J., & Muthen, B. (1989). Testing for the equivalence of factor covariance and mean structures: The issue of partial measurement invariance. Psychological Bulletin, 105(3), 456–466. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.105.3.456.

Byrne, B. M., Stewart, S. M., Kennard, B. D., & Lee, P. W. (2007). The Beck Depression Inventory-II: Testing for measurement equivalence and factor mean differences across Hong Kong and American adolescents. International Journal of Testing, 7(3), 293–309. doi:10.1080/15305050701438058.

Chandler, C. R. (1979). Traditionalism in a modern setting: A comparison of Anglo- and Mexican Americans value orientations. Human Organization, 38(2), 153–159.

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 233–255. doi:10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5.

Clarke, J. H., MacPherson, B. V., & Holmes, D. R. (1982). Cigarette smoking and external locus of control among young adolescents. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 23(3), 253–259. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.15.1.25.

Classen, C., Koopman, C., Angell, K., & Spiegel, D. (1996). Coping styles associated with psychological adjustment to advanced breast cancer. Health Psychology, 15(6), 434–437. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.15.6.434.

Cole, D., Rodriguez, J., & Cole, S. (1978). Locus of control in Mexicans and Chicanos: The case of the missing fatalist. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 46(6), 1323–1329. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.46.6.1323.

Coups, E. J., Stapleton, J. L., Manne, S. L., Hudson, S. V., Medina-Forrester, A., Rosenberg, S. A., & Goydos, J. S. (2014). Psychosocial correlated of sun protection behaviors among U.S. Hispanic adults. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. doi:10.1007/s10865-014-9558-5.

Cuéllar, I., Arnold, B., & González, G. (1995a). Cognitive referents of acculturation: Assessment of cultural constructs in Mexican Americans. Journal of Community Psychology, 23(4), 339–356. doi:10.1002/1520-6629(199510)23:4<339::AID-JCOP2290230406>3.0.CO;2-7.

Cuéllar, I., Arnold, B., & Maldonado, R. (1995b). Acculturation rating scale for Mexican Americans-II: A revision of the original ARSMA scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 17(3), 275–304. doi:10.1177/07399863950173001.

Curran, P. J., West, S. G., & Finch, J. F. (1996). The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 1(1), 16–29. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.16.

Darke, P. R., & Freedman, J. L. (1997). The belief in good luck scale. Journal of Research in Personality, 31(4), 486–511. doi:10.1006/jrpe.1997.2197.

Davis, S. N., Thompson, H., Gutierrez, Y. E., Boateng, S. G., & Jandorf, L. (2002). Breast cancer fatalism: ethnic differences and association with cancer screening. Annals of Epidemiology, 12(7), 491–492. doi:10.1016/S1047-2797(02)00294-6.

De Brabander, B., Hellemans, J., & Boone, C. (1999). Selection-pressure induces a shift towards more internal scores on Rotter's I-E locus of control scale. Current Research in Social Psychology, 4(1), 103–112.

Dempster, A. P., Laird, N. M., & Rubin, D. B. (1977). Maximum-likelihood estimation from incomplete data via the EM algorithm (with discussion). Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B, 39(1), 1–38. doi:10.2307/2984875.

Dettenborn, L., DuHamel, K., Butts, G., Thompson, H., & Jandorf, L. (2004). Cancer fatalism and its demographic correlates among African American and Hispanic women: effects on adherence to cancer screening. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 22(4), 47–60. doi:10.1300/J077v22n04_03.

Egede, L. E., & Ellis, C. (2010). Development and psychometric properties of the 12-item diabetes fatalism scale. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 25(1), 61–66. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-1168-5.

Esparza, O.A. (2005). Factors derived from fatalism scales and their relationship to health-related variables (Master’s Thesis). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 1430930).

Espinosa, L., & Gallo, L. C. (2011). The relevance of fatalism in the study of Latina’s cancer screening behavior: A systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 18(4), 310–318. doi:10.1007/s12529-010-9119-4.

Espinosa, L., & Gallo, L. C. (2013). Fatalism and cardio-metabolic dysfunction in Mexican-American women. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 20(4), 487–494. doi:10.1007/s12529-012-9256-z.

Farmer, D., Reddick, B., D’Agostino, R., & Jackson, S. A. (2007). Psychosocial correlates of mammography in older African American women. Oncology Nursing Forum, 34(1), 117–123. doi:10.1188/07.ONF.117-123.

Farris, B. E., & Glenn, N. D. (1976). Fatalism and familism among Anglos and Mexican Americans in San Antonio. Sociology and Social Research, 60(4), 393–402.

Flora, D. B., & Curran, P. J. (2004). An empirical evaluation of alternative methods of estimation for confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data. Psychological Methods, 9(4), 466–491. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.9.4.466.

Futa, K. T., Hsu, E., & Hansen, D. J. (2001). Child sexual abuse in Asian American families: An examination of cultural factors that influence prevalence, identification, and treatment. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 8(2), 189–209. doi:10.1093/clipsy.8.2.189.

Gonzalez, P. (2007). The design, construction, and testing of an instrument to measure Latina’s health beliefs about breast cancer and screening (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis database. (UMI No. 3279515).

Goodwin, R., Nizharadze, G., Luu, L. A. N., & Emelyanova, T. (1999). Glasnot and the art of conversation. A multilevel analysis of intimate disclosure across three former communist cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 30(1), 72–90. doi:10.1177/0022022199030001004.

Gorin, S. S. (2005). Correlates of colorectal cancer screening compliance among urban Hispanics. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 28(2), 125–137. doi:10.1007/s10865-005-3662-5.

Green, B. L., & Rodgers, A. (2002). Determinants of social support among low-income mothers: A longitudinal analysis. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29(3), 419–442. doi:10.1023/A:1010371830131.

Greiner, K. A., James, A. S., Born, W., Hall, S., Engelman, K. K., Okuyemi, K. S., & Ahluwalia, J. S. (2005). Predictors of fecal occult blood test (FOBT) completion among low-income adults. Preventive Medicine, 41(2), 676–684. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.12.010.

Gullatte, M. M., Brawley, O., Kinney, A., Powe, B., & Mooney, K. (2010). Religiosity, spirituality, and cancer fatalism beliefs on delay in breast cancer diagnosis in African American women. Journal of Religion and Health, 49(1), 62–72. doi:10.1007/s10943-008-9232-8.

Gwandure, C., & Mayekiso, T. (2012). Internal versus external control reinforcement in health risk and HIV and AIDS prevention. Journal of Applied Psychology, 42(7), 1599–1624. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00897.x.

Hollingshead, A. B. (1965). Two-factor index of social position. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Hollingshead, A. B. (1975). Four-factor index of social status. New Haven: Department of Sociology, Yale University. Unpublished manuscript.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118.

Joiner, T. E., Perez, M., Wagner, K. D., Berenson, A., & Marquina, G. S. (2001). On fatalism, pessimism, and depressive symptoms among Mexican-American and other adolescents attending an obstetrics-gynecology clinic. Behavior Research and Therapy, 39(8), 887–896. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(00)00062-0.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x.

Lawsin, C., DuHamel, K., Weiss, A., Rakowski, W., & Jandorf, L. (2006). Colorectal cancer screening among low-income African Americas in East Harlem: a theoretical approach to understanding barriers and promoters to screening. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 84(1), 32–44. doi:10.1007/s11524-006-9126-6.

Lipkus, I. (1991). The construction and preliminary validation of a global belief in a just world scale and the exploratory analysis of the multidimensional belief in a just world scale. Personality & Individual Differences, 12(11), 1171–1178. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(91)90081-L.

Little, T. D. (1997). Mean and covariance structures (MACS) analyses of cross-cultural data: Practical and theoretical issues. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 32(1), 53–76. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr3201_3.

Luten, A. G., Ralph, J. A., & Mineka, S. (1997). Pessimistic atributional style: Is it specific to depression versus anxiety versus negative affect? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35(8), 703–719. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(97)00027-2.

MacCallum, R. C., Widaman, K. F., Keith, F., & Zhang, S. (1999). Sample size in factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 4(1), 84–99. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.4.1.84.

Magai, C., Consedine, N., Conway, F., Neugut, A., & Culver, C. (2004). Diversity matters: Unique populations of women and breast cancer screening. Cancer, 100(11), 2300–2307. doi:10.1002/cncr.20278.

Marsh, H. W., Hey, J., Roche, L. A., & Perry, C. (1997). Structure of physical self-concept: Elite athletes and physical education students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(2), 369–380. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.89.2.369.

Mayo, R. M., Ureda, J. R., & Parker, V. G. (2001). Importance of fatalism in understanding mammography screening in rural elderly women. Journal of Women and Aging, 13(1), 57–72. doi:10.1300/J074v13n01_05.

Merriam-Webster’s collegiate dictionary (1993). (10th ed.) Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster.

Moneyham, L., Seals, B., Sowell, R., Hennessy, M., Demi, A., & Brake, S. (1997). The impact of HIV on emotional distress of infected women: Cognitive appraisal and coping as mediators. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice: An International Journal, 11(2), 125–145.

Moore, M. K., & Neimeyer, R. A. (1991). A confirmatory factor analysis of the Threat Index. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(1), 122–129. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.60.1.122.

Morling, B., & Evered, S. (2006). Secondary control reviewed and defined. Psychological Bulletin, 132(2), 269–296. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.269.

Neff, J. A. (1993). Life stressors, drinking patterns, and depressive symptomatology: Ethnicity and stress-buffer effects of alcohol. Addictive Behaviors, 18(4), 373–387. doi:10.1016/0306-4603(93)90054-D.

Panter, A. T., Tanaka, J. S., & Wellens, T. R. (1992). The psychometrics of order effects. In N. Schwarts & S. Sudman (Eds.), Context effects in social and psychological research (pp. 249–264). New York: Springer.

Parker, S., & Kleiner, R. (1966). Mental illness in the urban Negro community. New York: Free Press.

Pearlin, L. I., & Schooler, C. (1978). The structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 19(1), 2–21.

Peck, D. L. (1981). A comparison of the worldview of older and younger persons. Corrective & Social Psychiatry & Journal of Behavior Technology, Methods & Therapy, 27(1), 62–68.

Peterson, C., & Vaidya, R. S. (2001). Explanatory style, expectations, and depressive symptoms. Personality and Individual Differences, 31(7), 1217–1223. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00221-X.

Peterson, C., Semmel, A., von Baeyer, C., Abramson, L., Metalsky, G., & Seligman, M. (1982). The attributional style questionnaire. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 6(3), 287–300. doi:10.1007/BF01173577.

Pines, E.W. (2002). The effect of cancer fatalism on African American women’s compliance with mammography screening (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses databases. (UMI No. 3055818).

Powe, B. D. (1995). Fatalism among elderly African americans: effects on colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Nursing, 18(5), 385–392. doi:10.1097/00002820-199510000-00008.

Powe, B. D., Hamilton, J., & Brooks, P. (2006). Perceptions of cancer fatalism and cancer knowledge: a comparison of older and younger African American women. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 24(4), 1–13. doi:10.1300/J077v24n04_01.

Pritchard, D., & Smith, M. (2004). The psychology and philosophy of luck. New Ideas in Psychology, 22(1), 1–28. doi:10.1016/j.newideapsych.2004.03.001.

Ross, C. E., Mirowsky, J., & Cockerham, W. C. (1983). Social class, Mexican culture, and fatalism: Their effects on psychological distress. American Journal of Community Psychology, 11(4), 383–399. doi:10.1007/BF00894055.

Rothbaum, F., Weisz, J. R., & Snyder, S. S. (1982). Changing the world and changing the self: A two-process model of perceived control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42(1), 5–37. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.42.1.5.

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs, 80(1), 1–28. doi:10.1037/h0092976.

Rudomo, T., & Hale, A. R. (2003). Managers’ attitudes towards safety and accident prevention. Safety Science, 41(7), 557–574. doi:10.1016/S0925-7535(01)00091-1.

Russell, K. M., Perkins, S. M., Zollinger, T. W., & Champion, V. L. (2006). Sociocultural context of mammography screening use. Oncology Nursing Forum, 33(1), 105–112. doi:10.1188/06.ONF.105-112.

Sanchez, W., & Garriga, O. (1996). Control theory, reality therapy and cultural fatalism: Towards an integration. Journal of Reality Therapy, 15(2), 30–38.

Schafer, J.L. (2000). NORM: Multiple imputation of incomplete multivariate data under a normal model (version 2.03) [Computer software]. Retrieved from http://www.stat.psu.edu/~jls/misoftwa.html.

Schedlowski, M., Fluge, T., Richter, S., Tewes, U., Schmidt, R. E., & Wagner, T. O. F. (1995). B-endorphin, but not substance-P is increased by acute stress in humans. Psychoneuroendrocrinology, 20(1), 103–110. doi:10.1016/0306-4530(94)00048-4.

Scheier, M. F., & Bridges, M. W. (1995). Person variables and health: Personality predispositions and acute psychological states as shared determinants for disease. Psychosomatic Medicine, 57(3), 255–268.

Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1992). Effects of optimism on psychological and physical well-being: Theoretical overview and empirical update. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 16(2), 201–228. doi:10.1007/BF01173489.

Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S., & Bridges, M. W. (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A re-evaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal Personality and Social Psychology, 67(6), 1063–1078. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1063.

Seligman, M. E. P. (1975). Helplessness: On depression, development, and death. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman.

Shen, L., Condit, C. M., & Wright, L. (2009). The psychometric property and validation of a fatalism scale. Psychology and Health, 24(5), 597–613. doi:10.1080/08870440801902535.

Somlai, A. M., Kelly, J. A., Heckman, T. G., Hackl, K., Runge, L., & Wright, C. (2000). Life optimism, substance use, and AIDS-specific attitudes associated with HIV risk behavior among disadvantaged innercity women. Journal of Women’s Health & Gender-Based Medicine, 9(10), 1101–1111. doi:10.1089/152460900446018.

Spitzer, R., Williams, J., Kroenke, K., Linzer, M., de Gruy, F., Hahn, S., & Johnson, J. G. (1994). Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care: The PRIME-MD 1000 study. Journal of the American Medical Association, 272(22), 1749–1756. doi:10.1001/jama.1994.03520220043029.

Storch, E. A., Roberti, J. W., Heidgerken, A. D., Storch, J. B., Lewin, A. B., Killiany, E. M., & Geffken, G. R. (2004). The Duke Religion Index: A psychometric investigation. Pastoral Psychology, 53(2), 175–181. doi:10.1023/B:PASP.0000046828.94211.53.

Talbert, P.Y. (2007). An analysis of the relationship of fear and fatalism with breast cancer screening among a selective target population of African American middle class (AMMC) women (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis database. (UMI No. 3252461).

Tanzer, N. K. (2005). Developing tests for use in multiple languages and cultures: A plea for simultaneous development. In R. Hambleton, P. Merenda, & C. D. Spielberger (Eds.), Adapting educational and psychological tests for cross-cultural assessment. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Vyas, K. J., Limneos, J., Qin, H., & Mathews, W. C. (2014). Assessing baseline religious practices and beliefs to predict adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected persons. AIDS Care, 26(8), 983–987. doi:10.1080/09540121.2014.882486.

Wade, T. J. (1996). An examination of locus of control of control/fatalism for blacks, whites, boys, and girls over a two year period of adolescence. Social Behavior and Personality, 24(3), 239–248. doi:10.2224/sbp.1996.24.3.239.

Wagenaar, W. A., & Keren, G. B. (1988). Chance and luck are not the same. Journal of Behavioural Decision Making, 1(2), 65–75. doi:10.1002/bdm.3960010202.

Wallston, K. A., Malcarne, V. L., Flores, L., Hansdottir, I., Smith, C. A., Stein, M. J., & Clements, P. J. (1999). Does God determine your health? the God locus of health control scale. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 23(2), 131–142. doi:10.1023/A:1018723010685.

Weiner, B. (1974). Achievement motivation and attribution theory. Morristown: General Learning Press.

West, S. G., Finch, J. F., & Curran, P. J. (1995). Structural equation models with non-normal variables: Problems and remedies. In R. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues and applications (pp. 56–75). Newbury Park: Sage.

Wheaton, B. (1983). Stress, personal coping resources, and psychiatric symptoms: An investigation of interactive models. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(3), 208–229. doi:10.2307/2136572.

Williamson, A. M., Feyer, A. M., Cairns, D., & Biancotti, D. (1997). The development of a measure of safety climate: The role of safety perceptions and attitudes. Safety Science, 25(1–3), 15–27. doi:10.1016/S0925-7535(97)00020-9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Esparza, O.A., Wiebe, J.S. & Quiñones, J. Simultaneous Development of a Multidimensional Fatalism Measure in English and Spanish. Curr Psychol 34, 597–612 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-014-9272-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-014-9272-z