Abstract

By most measures, the impact of international human rights law ratification in the Arab Gulf region primarily in the 1990s and 2000s has been minimal. Scholars have found little evidence of correlation between ratification of the core human rights conventions with the minimal improvements in human rights practice in the region. Ratification of most human rights instruments Arab Gulf states in recent decades has, however, offered new cases from which to explore the impact of international human rights law in countries where human rights monitors find protections to be most limited. Using the case of Kuwait’s ratification of the Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), this article examines the impact of ratification in 1994 on discourses on discrimination against women in national press on human rights in the country. Through analysis of reporting in national newspaper Al-Anba, the article identifies how ratification has shaped the language used in national press reporting on women’s rights to increasingly reference the convention and frame rights violations in the language of “discrimination.” In tracing these connections between the convention and related content in local press, the article identifies new avenue to explore the “impact” of human rights treaty ratification, even when formal changes in laws and policies so far have been limited.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

When the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was introduced at the United Nations in 1948, proponents of a global human rights agenda entered an era of optimism. Delegates such as Charles Habib Malik, Lebanese philosopher and diplomat, expressed great hope in a new future for the protection of human rights globally with this new “potent ideological weapon” for the protection of human rights (Darraj 2010, p. 83). Since then, the records of international human rights instruments in substantially improving human rights, globally as well as particularly in the Arab world, have been limited. Despite widespread ratification of core human rights treaties primarily in the 1990s and 2000s, Arab states, and most markedly, the states of the Arab Gulf including Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Oman, and Kuwait, continue to score the lowest in global human rights rankings.Footnote 1

There is substantial evidence in the Arab Gulf to disappoint optimistic proponents of the impact of international human rights law. However, this article offers a more optimistic view. Kuwait’s ratification of CEDAW in 1994 and broader engagement with the UN CEDAW Committee since ratification offers evidence of correlation to the increased use of the language of preventing discrimination against women in the local press reporting. Drawing on the concepts of norm localization (Acharya 2004) and vernacularization (Levitt and Merry 2009), I argue that these changes evidence the translation and embedding of global norms, as global human rights language has been connecting with language employed to shape specific debates on Islam and women’s rights in Kuwait. In illustrating how CEDAW and associated women’s rights language is being incorporated in domestic press coverage of policies affecting women in Kuwait, this article helps illustrate the nature of global human rights norm diffusion in states where traditional measures of impact have shown minimal results.

Since Kuwait ratified CEDAW in 1994, some progress enhancing women’s rights has been achieved, suggesting the treaty may at least be correlated with reforms, although evidence of the direct connection has been limited. This has been evident most prominently in three areas: reforms granting women the right to vote and stand in parliamentary and local elections in 2005; legal reform to enhance women’s autonomy, most prominently reflected in the 2009 amendment to the passport law allowing women to obtain passports without spouse consent; and the growth of reform initiatives to enhance women’s rights, such as the Abolish 153 campaign to end discriminatory laws governing honor crimes. A law against domestic violence has also been proposed in January 2018. Despite considerable opposition, there is an active women’s rights movement in Kuwait, with various reform efforts supported by Islamists and liberal human rights activists alike. I argue that this recent history of women’s rights activism in Kuwait has been marked by the increased use of the term “discrimination against women” in human rights discourse since ratification of CEDAW including through media outlets, and suggest how an understanding of this trend can offer new avenues for understanding the impact of international human rights law. While not the only factor, CEDAW is part of this overall framing process of human rights beyond the government’s own actions in direct relation to the treaty and reflects an impact most substantially visible in the realm of subtle changes in language: this is indicated by the increased incorporation of the terminology of “non-discrimination” alongside the growing discussion of CEDAW in the context of women’s rights reporting in Kuwaiti press.

Literature in international relations drawn primarily from political science perspectives on state power and incentives, and which analyzes the relationships between domestic and international politics, has grown to address questions about the impact of international law and broadly frames the theoretical basis for this analysis. A scholarship has intensified to assess the expansion of the international legal realm into a multiplicity of international treaties, conventions, agreements, and declarations aiming to influence and regulate the conduct of individual states contributing to a growing codification, or “legalization,” of the international sphere (Abbott, Keohane, Moravcsik, Slaughter and Snidal 2000, pp. 115–130). The study of international law has taken particular prominence among political scientists over the past decade, as, along with globalization, the field has grown increasingly interested in work on “the development, spread and impact of international legal norms, agreements, and institutions” on state power brokering and political contestation and development (Hafner-Burton et al. 2012, p. 47). The body of literature crosses disciplines but includes work on human rights norms (Wiener 2004, 2007; Barnett and Finnemore 2004) examining where international law consolidates global human rights norms and is interpreted variously in domestic settings. However, because the international sphere lacks direct coercive enforcement mechanisms, political scientists have also fundamentally challenged the “strength” of international law—and even its status as “law” at all (Goldsmith and Posner 2005).Footnote 2 The ability of these international documents to have an impact and to shape individual and state behavior remains debated. For those concerned with human rights, an area of high state commitment but sometimes relatively low compliance, any evidence of the real force of these instruments remains difficult to gather and prove.

I argue that international human rights law has been important despite the challenges in achieving compliance and, even if not directly improving human rights conditions, international human rights law has had other effects in helping solidify and promote the international language of human rights in local discourses, a particularly powerful tool in spaces in which channels for human rights advocacy are otherwise limited. Existing international relations theories have weaknesses in accounting for the nuanced and complex impacts of international law, particularly in cases where states fail to comply with their international legal commitments. I address these weaknesses by considering the subtle dynamics of impact through its impact on local press.

Newspapers, in the sense of the topics and perspectives they cover and language they employ, provide useful sites for examining political contestation and uptake of human rights concepts in different contexts. Although the media landscape is shifting towards new media, online formats both globally and in the Gulf (an area discussed further in the paper including as an area ripe for further research), newspapers have long been and continue to serve as an important site for examining a diversity of political contexts and, particularly, as a format reflecting political change processes in varied contexts where tracking debate in the domestic space is otherwise limited. Their examination requires contextualization based on the political environment. Ban et al. (2019), for example, identify newspaper coverage (or the “relative amount of space devoted to particular subjects in newspapers”) as a key measure of political power in varied contexts (Ban et al. 2019, p. 661). Traditional newspapers increase and improve public knowledge about politics and other societal issues (and research suggests that online media, including non-paper news sites, is seen to similarly improve political awareness but with some differing and more diffuse effects). While political bias is strong in contexts of authoritarianism and state-controlled media landscapes, these sites can still prove useful areas for tracking policy priorities and understandings in domestic framings of issues through the use of language, selection of topics, and political framing and focus of newspaper coverage to shed some light on the domestic political environment (De Waal and Schoenbach 2008).

Using online available information, I illustrate the use of CEDAW and its language in Kuwaiti human rights discourse by demonstrating the increased use of the phrase “discrimination against women” [al-tamyīz ḍidd al-mar’ah] alongside the growing use of direct references to the CEDAW in Al-Anba, a prominent, conservative, and pro-government Kuwaiti Arabic-language newspaper, to reflect some shift in domestic framing and understanding of women’s rights issues over time. This is observed primarily since 2006, a period of greater press freedom in Kuwait, and as such, this time period is the focus of analysis for this article to view how a generally more free press has shaped and covered the topic of women’s rights in new and changing ways. The period starting with 2006 was selected for a number of reasons, including the availability of a full online database of the newspaper starting this year, the correspondence to some significant shifts in the women’s rights movement at this time (including the 2005 withdrawal of reservations and enfranchisement of women), and this provided a key turning point from which to considered the ways in which women’s rights discourse and debate have developed as women’s rights reforms were unfolding most significantly in the period following ratification. This newspaper in particular was selected because of its conservative slant; in this newspaper, the adoption of global women’s rights vocabulary was not the norm previously and women’s rights coverage has been less prominent than the language and content contained in some more liberal newspapers. References to CEDAW as well as use of the terminology of preventing “discrimination” against women in press coverage of women’s issues have together gained prominence in articles in Al-Anba over time, suggesting CEDAW has contributed at least in some ways to the spread of the terminology contained in the Convention in vernacular in Kuwait on human rights, among the influences of wider global, regional, and national women’s rights activism. The articles identified indicate several key issue areas specific to the Kuwaiti context in which CEDAW and the concept of non-discrimination have been particularly relevant: the rights of women (and their children) who marry non-Kuwaitis (including the Bidun community), women’s rights in the family (as they relate to custody and divorce and legal autonomy from fathers and husbands), women’s labor rights (including regulations governing the hours in which women can work and the positions they can hold), and women’s political representation. Reports in Al-Anba conveying ideas supportive of CEDAW principles around these issue areas sometimes discuss CEDAW directly and sometimes indirectly, and occasionally discuss respect for CEDAW with the caveat of needing to ensure compatibility with Islam, framing CEDAW concepts of non-discrimination as they fit within a particular legal and social context and as they relate to particular issues in Kuwait.

Growing direct mentions of CEDAW and the concept of non-discrimination as they relate to these issues in Al-Anba articles suggest that CEDAW has increasingly become an important tool in local press for discussion about women’s rights in Kuwait. This indicates that CEDAW should be further explored for its impact on national human rights discourses, the possibilities of which are discussed in the concluding section. Avenues for further research and possible methodologies to apply are also discussed in concluding comments.

Contextualization

The concepts of norm diffusion, norm vernacularization, and localization can help scholars establish whether—and, if so, to what extent—international human rights laws play a role in the development and spread of human rights norms in different local contexts, and how they travel from the global to the local spaces. Such concepts have been the subject of increasing scholarly attention. Margaret Keck and Kathryn Sikkink argue that, while human rights norms are well institutionalized in today’s collection of international regimes and organizations, international human rights institutions often fail to “diffuse” these norms to state practice because (1) international norms about human rights are highly contested and (2) these norms challenge state rule over society and national sovereignty. Because of these challenges to diffusion, it is not human rights institutions alone, they argue, but the existence of transnational advocacy networks (TANs) that enhance and often help facilitate norm diffusion to succeed in areas of human rights. The successful diffusion of human rights norms internationally “crucially depends on the establishment and the sustainability of networks among domestic and transnational actors who manage to link up with international regimes…,” when this process succeeds, international norms can be “internalized and implemented domestically” in a “process of socialization” (Keck and Sikkink 1999, pp. 4–5.)

The problem with this literature is that it focuses almost exclusively on the impact of norms in the sense of the success of transnational advocates and norms entrepreneurs to achieve compliance measured in the form of the implementation of laws and policies. Finnemore and Kathryn Sikkink, for example, define the process in which norms diffuse as based on a “norm life cycle”—consisting of “norm emergence,” “norm cascade,” and “norm internalization” (Finnemore and Sikkink 1998, pp. 887–917; 895). The idea is that norms are “internalized” (or successfully diffuse to become cemented shared expectations) when they “acquire a taken-for-granted quality and are no longer a matter of broad public debate” (Finnemore and Sikkink 1998, p. 895). The suggestion is therefore that broad public debate on a norm indicates the norm has not been internalized and remains in the “cascade” phase in which norms are still being contested, and this does not account for cases, such as those discussed in this paper, in which the public debate has shifted in nature or tone—a possible form of “diffusion” too subtle to fit into these existing understandings of internalization.

A useful contribution to the scholarship on norm diffusion has been the work of Amitav Acharya, who coined the term “norm localization” in a 2004 article arguing using cases in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) that international norms “diffuse” (or spread) most successfully when “local agents reconstruct the norms to ensure a better fit with prior local norms” (Acharya 2004, pp. 239–275). This paper orients its perspective on norm diffusion around Acharya’s contribution by building on his theory that “localizing” norms is key to the diffusion of human rights norms. By extension, in order for norms to localize, norms must be adapted to a vocabulary that resonates with a specific context.

Further developing ideas about how human rights norms can travel and even take on new meanings in new contexts, Peggy Levitt and Sally Engle Merry have developed the concept of “vernacularization” to discuss the appropriation and local adoption of global human rights normsFootnote 3 (Acharya 2018, p. 58). In their 2009 study of local uses of global women’s rights norms in Peru, China, India, and the USA, Levitt and Merry describe this process of vernacularization as a process of norm translation in which norms do not simply transfer from one context to another, but indeed as they localize, they take on new contours. They write: “As women’s human rights ideas connect with a locality, they take on some of the ideological and social attributes of the place, but also retain some of their original formulation” (Levitt and Merry 2009, pp. 441–461; 446). In their view, instead of seeing diffusion as the direct transfer of international human rights ideas as contained in UN conventions to local contexts supported by international and transnational movements and advocates, the so-called vernacularizers (the leaders and staff in local organizations) re-define and adapt these concepts to assimilate the norm into local discourse (Levitt et al. 2008). This can potentially promote international support for local human rights activists and growing national acceptance of an international norm, while it can also, sometimes simultaneously, prompt national resistance to accepting a global norm.

Evidence in support of the concept of vernacularization is documented, for example, in Koh et al.’s 2017 article on vernacularization in labor rights in Singapore, where civil society actors were able to advocate for a day off work for migrant domestic workers by adapting global labor rights norms and appealing to local morality and appealing to local Singaporean business culture (Koh et al. 2017, pp. 89–104). Through this process, the meanings of human rights extend and change beyond their original legal meanings, which should be expected in the context of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), as is clear in instances when the language of rights and equality in Islamic contexts sometimes take on new meanings, to converge with existing language of duties, responsibilities, and other local framings of rights. It is reasonable to assume that the process whereby meanings of human rights as they are vernacularized is necessary in order to facilitate some implementation of international legal standards, even if as a result these understandings of human rights are changed to fit local contexts (Levitt and Merry 2009, p. 460).

As Beth Simmons suggests, the ratification of an international human rights treaty holds “unique features” compared with broad international norms. “A ratified treaty recommits the government to be receptive to rights demands. Ratification is not just a costly signal of intent; it is a process of domestic legitimation that some scholars have shown raises the domestic salience of an international rule” (Simmons 2008, p. 144). Simmons argues that in certain cases, local populations can anchor their activism around ratification to hold their government to account. The power of international law to help bolster activism to support human rights norms is visible, she claims, for example, in Japan, where CEDAW ratification without reservations helped social groups in Japan mobilize to advocate for greater respect for women’s rights, ultimately reflected in landmark domestic legislation on women’s rights including protections for equal employment “that likely would not have existed were it not for the external negotiation of the CEDAW” (Simmons 2009, p. 240).

I find that the ratification of CEDAW in the case explored attributes particularly legitimacy to the human rights norms addressed in this analysis, which can, at times, help frame and support local activism. The GCC states’ ratification of core human rights treaties such as CEDAW has, as Simmons would suggest, helped raise the domestic salience of some of the norms enshrined in these treaties, even if the norms broadly contained in these treaties are not fully internalized and enforced in the Kuwait and its GCC neighbors.

Kuwait and CEDAW

Kuwait holds a comparatively progressive constitution compared to its Gulf neighbors. First drafted in 1962, Article 29 of the Constitution provides for all people to be “peers in human dignity,” with “equal public rights and obligations” (Kuwait Constitution). Kuwait acceded to CEDAW in 1994, before any other GCC state. After this point as the rest of the Gulf states ratified CEDAW primarily in the 2000s, all six states made some mention of possible conflict with Islam in reservations, understandings, and declarations (RUDs) submitted upon ratification, suggesting the treaty, though formally accepted in the region, was viewed as standing at odds with some of the key features of the Gulf states’ interpretations of Islamic faith.

The GCC states are not alone in entering concerns to CEDAW related to Islam. Some 16 UN states mentioned concern related to compatibility with Islam in initial RUDs.

Saudi Arabia entered a single, sweeping reservation upon ratification saying,

In case of contradiction between any term of the Convention and the norms of Islamic law, the Kingdom is not under obligation to observe the contradictory terms of the Convention.Footnote 4

Oman also entered a sweeping reservation citing Islam.Footnote 5

The United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Bahrain, and Qatar’s reservations were more specific (covering issues including marriage, voting, and nationality).

Kuwait’s initial reservation stated,

Reservations: [concerning equal rights to hold office],

1. The Government of Kuwait enters a reservation regarding article 7 (a) inasmuch as the provision contained in that paragraph conflicts with the Kuwaiti Electoral Act, under which the right to be eligible for election and to vote is restricted to males.

2. Article 9, paragraph 2 [concerning equal right to pass nationality]

The Government of Kuwait reserves its right not to implement the provision contained in article 9, paragraph 2 of the Convention, inasmuch as it runs counter to the Kuwaiti Nationality Act, which stipulates that a child's nationality shall be determined by that of his father.

3. Article 16 (f) [concerning children’s rights]

The Government of the State of Kuwait declares that it does not consider itself bound by the provision contained in article 16 (f) inasmuch as it conflicts with the provisions of the Islamic Shariah , Islam being the official religion of the State.

4. The Government of Kuwait declares that it is not bound by the provision contained in article 29, paragraph 1 [concerning right of referral to the ICJ].

Eight months later, the government of Kuwait withdrew its reservation on 9 December 2005 related to Article 7(a) concerning Kuwait’s Electoral Act, citing changes to the law allowing women to vote.Footnote 6 Nisrine Abiad identifies this change as important for recognizing the variance in the ways in which Muslim countries communicate their positions on women’s rights. For example, Pakistan reserved to various parts of the CEDAW without referencing Islam, using secular law “as an excuse to place limitations to CEDAW which are really motivated by Sharia” (Abiad 2008, p. 92). Kuwait’s initial statement about electoral rights, not directly linked to Sharia but perhaps implicitly related, clearly illustrates the possibility for certain interpretations of Islam and women’s rights as initially expressed in reservations to be open to change.

Kuwait’s initial report to the CEDAW committee (due 1999, submitted 2004) contained a number of assurances that women are treated equally in Kuwait and, particularly, under Islamic law. However, the meetings also included statements about the inflexibility of Islamic law, and Kuwait’s representatives claimed that numerous requests from the CEDAW committee to reform the law could not be followed because Islamic law could not be changed.

The initial 2004 report claimed Kuwaiti law was compatible with principles of equality by issuing assurances of equality provided for in the Kingdom’s system of law based on Islam, saying,

Under the Kuwaiti Constitution, the principles of equality and nondiscrimination are fundamental constituents of Kuwaiti …

It is clearly evident … that the State is committed to the achievement of equal rights and obligations for women and men in a manner consistent with the nature of Kuwaiti society and the provisions of Islamic law which regulate personal status in Kuwait (CEDAW/C/KWT/1-2, 13).

Kuwait’s second report in 2010 started by framing an understanding of Kuwait’s law informed by Islam as being “naturally” compatible with CEDAW principles of equality and non-discrimination (although there is no specific gender equality clause in the Constitution). The statement begins,

The Kuwaiti Constitution is based on well-established principles, which naturally include those of equality and non-discrimination between men and women in the light of the provisions of Islamic law, as is clear from the following: All people are equal in human dignity and in rights and duties before the law, without distinction as to colour, language or religion, as stated in article 29 of the Constitution (CEDAW/C/KWT/3-4, 4).

Still, despite assurances of compatibility, Kuwaiti officials claimed, again, that certain aspects of law that concern the CEDAW Committee cannot be changed because of Islam, saying,

Mr. Almutairi (Kuwait) said that, in the light of the fact that Kuwaiti law drew on the principles of Islamic law, which governed all matters relating to personal status, marriage, divorce and inheritance, the legal provisions pertaining thereto could not be amended. Muslims were expected to abide by those principles (CEDAW/C/SR.1012, 9)

Kuwaiti representatives have, at the same time, suggested these rules under Islam could, in fact, be changed, and introduced the concept of the necessity for social change to take place gradually in a 2010 CEDAW Committee hearing,

Mr. Razzooqi (Kuwait) Said that...Nothing in Islam stood in the way to the achievement of equality between men and women. However, it took time for society to change. .... (CEDAW/C/SR.1012, 11)…Kuwaiti society was gradually embracing the modern world. That process of change was most apparent among the younger generation of Kuwaitis, as was demonstrated by a low marriage rate and parents electing to have fewer children in order to guarantee them a better quality of life (CEDAW/C/SR.1012, 9).

These discussions of a “gradually” “modernizing” Kuwait have continued. In a 2019 report, more specific reforms were explored; for example, Kuwait representatives raised an “ongoing discussion in the Kuwaiti National Assembly of a draft act concerning the Ja’fari interpretation of personal status matters…in keeping with the desire of the State of Kuwait to move forward with the development of its legislation” (CEDAW/C/KWT/CO/5/Add.1, 4) suggesting “modernization” of some laws to comply with CEDAW was a gradual, ongoing process.

These CEDAW dialogues must be understood in the broader context of politics in Kuwait. Strong conservative opposition against the complete “equality” among genders in Kuwait is being balanced alongside significant domestic women’s rights activism in support of most equal rights clauses contained in CEDAW—these dynamics are explored in the following section, to support the contextual grounding of the newspaper analysis on the concept of discrimination against women in Kuwait in the later section of the paper.

Reforms and Activism in Kuwait in Relation to CEDAW

To explore how CEDAW has been enacted and taken form more specifically within domestic political settings, this section begins by laying the relevant history of the women’s rights movement in Kuwait—including the extension of the right to vote to women, the resultant partial withdrawal of Kuwait’s reservation to CEDAW, and other women’s rights progress—as illustrative of broader changes in the integration of global human rights norms related to CEDAW ratification in Kuwait. Ratification has been part of this story; it is both reflective of normative change occurring in Kuwait and a factor in the broader integration of global women’s rights norms in Kuwait. Below, the changes in the period before and after ratification will be briefly outlined and then the nature of press reporting on women’s rights since 2006 is discussed.

Women’s rights advocacy in Kuwait long predates CEDAW ratification. In the early 1960s, a number of women’s societies formed in Kuwait, including the Arab Women Development Society (AWDS) and the Women’s Cultural and Social Society (WCSS) (and affiliated group Nadi al-Fatat (Girls’ Club)), under the umbrella of the Kuwaiti Women’s Union. The AWDS was more liberal and advocated particularly for women’s political rights. Nouria Al-Sadani, the AWDS president, was the first to submit a complaint to the National Assembly demanding the right to vote in 1971, but faced resistance, and the AWDS was eventually shut down (Shultziner and Tetreault 2011, pp. 1–25).

CEDAW ratification took place at the beginning of a gradual period of political and social change in Kuwait. As Kuwait’s Amir Jaber was balancing the growth of Islamist groups in Kuwait, he ratified CEDAW by Amiri decree in 1994, attempted to grant women the right to vote and stand for office by decree in 1999, but this was overturned by conservative and Islamist forces in the National Assembly. As one interviewee working as an academic and government advisor in Kuwait explained, this failed initial attempt to enfranchise women in 1999 demonstrates the power of the traditional and tribal power contestation in the Assembly with Islamists and conservatives holding onto power.Footnote 7 It was only six years after the Amir initial attempt to grant female suffrage that women were granted the right to vote in 2005 by an extremely close vote in the National Assembly of 25-23.

When women eventually gained the right to vote in Kuwait in 2005, some 10 years after CEDAW ratification, the hard-won reform was met with virulent Islamist pushback. Upon announcement of the reforms, Kuwaiti women’s activist Lullala al 426 Mulla proclaimed, “it’s about time.” International audiences lauded the reform as an 427 end to “decades-long struggle” promising to “redefine the city-state’s political landscape. Still, after this period of change, women were eligible and stood as candidates for election, but progress was slow – women did not win in the next two parliamentary elections, the first in April 2006 and the next in May 2006. The WCSS campaigned to encourage women to vote, framing this as a ‘right,’” with posters reading “For your voice to rise…Use your right (haqq): Get involved, vote, participate in the 2006 elections” (Global Fund for Women). Despite women turning out to vote and initiatives promoting women’s right to vote and stand for elections, only later in May 2009 were the first four women elected to parliament and a number of women have been elected since in elections in 2012, 2013 and 2016 (Shalaby 2015). (Fattah 2005) Since gaining the right to vote and run for office, a number of prominent women have gained positions and have contributed to ongoing debate on women’s rights in Kuwait. Massoma Al Mubarak, a former Kuwaiti cabinet minister, criticized Islamists’ views publicly in parliament, calling equal treatment of citizens. Aseel Awadi served in the National Assembly from 2009 to 2012 and advocated for equal treatment of all citizens and freedom of conscience; however, she was targeted by Islamists, led by Mohammed Haief, who accused her of insulting Islam and committing apostasy. (Olimat 2011) Islamists are not, however, monolithic in their views on women in Kuwait: there is a split among Sunni Islamists and Muslim Brotherhood members, some of whom strongly support women’s movements in Kuwait, while Salafi-Islamists strongly oppose women’s political activity as a violation of their views grounded in Islam.Footnote 8 In 2009, a landmark reform to the passport law was enacted to allow women to gain passports without the consent of their husbands (Reform to Article 15 of the Kuwaiti Law on Passports). The country’s commitment to the treaty has been used to anchor some of these local arguments for greater equality. The ratification of CEDAW could be seen as correlated with the momentum and frequency of movements for change, and a set of real reforms achieved enhancing women’s rights since ratification, for example, related to women’s gaining the right to vote and run for office in 2005 as well 2009 reforms to the passport law. The question remains as to how significant CEDAW was to these changes, and whether or not it could lead to more extensive reforms, as many areas of discrimination against women remain in Kuwait. For example, Kuwaiti women married to non-Kuwaitis, unlike Kuwaiti men, cannot pass citizenship to their children or spouses, and the law does not prohibit domestic violence or marital rape and restricts certain hours and roles that women can work. Advocates continue to call for reforms to prevent discrimination against women across these areas.

The momentous passage of women’s suffrage in Kuwait in the years following CEDAW ratification could be more clearly attributed to domestic political dynamics in Kuwait than directly to international factors such as the CEDAW, although the CEDAW is one factor among many contributing to framing and supporting both government and grassroots reform efforts. Despite some grassroots movement and the recognition of the KSHR, the women’s suffrage bill seemed to have passed 2005 due to the concerted efforts in the government to advance a top-down change. Doron Shultziner and Mary Ann Tetreault argue that the Amir was motivated to pass the bill in 2006 to “avoid another humiliating defeat in parliament.” They suggest that the Amir succeeded thanks to concerted efforts including the government promotion of the bill on national television, lobbying in parliament, and advocacy from elites such as Mohammad al-Sager, head of the Foreign Affairs Committee, supported by global liberal advocates, and even alleged payouts for government employees who supported the cause (Ibid, 3). Shultziner and Tetreault also attribute the victory to the government’s efforts alongside the activism of a relatively small number of Kuwaiti middle- and upper-class women, supported by personal motivation, international support, and transformative contextual events (Ibid). Here, CEDAW is part of this larger picture, perhaps providing language and framing for international and domestic movements, without clearly serving as the direct causal link to women’s suffrage.

Women’s rights movements including the suffrage movement also incited resistance and backlash in Kuwait where a welfare state funded by oil and patriarchal and tribal social structure helped bolster the strength of the idea of a traditional family structure. As Tetreault and Schultziner claim, “Arguments for women’s political rights couched in the language of human rights were often seen as threatening and resulted in more opposition than support by Kuwaiti women: conservative women also organized to curtail suffragist campaigns, for example, by collecting hundreds of signatures on petitions opposing women’s suffrage” (Ibid, 6). In this context, women’s rights efforts succeeded when they appealed not to international sentiments but to nationalist sentiment that tied the idea of women’s rights with the idea of a bright future for Kuwait, attacking opponents as being anti-progress. As argued by Haya al-Mughni, Islamist women and men became key to the success of women’s rights movements, where Islamist women played a formative role in interpreting women’s rights in Kuwait, often partnering with liberal women activists, engaging in the process of reinterpreting Islamic sources through the concept of ijtihad (Al-Mughni 2010).

In 2005, the hizb al-ummah Islamist group in Kuwait declared support for women’s political participation, weakening the authority of religious opposition (Al-Mekaimi 2008). The Islamist group the Islamic Constitutional Movement in Kuwait announced support for women’s right to vote, but not for women to run for office, citing the need for gradual change (Al-Mughni 2010). Some Islamists seemingly pushed for improving women’s legal status in Kuwait as part of their support for the position of the marginalized Bidun population. These Salafi supporters of women’s rights have been labeled “reluctant feminists,” who support the idea of certain patriarchal norms such as male dominance over the family and the home, but as a result of their larger interests have supported a broad swath of initiatives leading to strengthened female citizenship rights and even expanding labor rights for women (Maktabi 2016, p. 25).

CEDAW remains clearly a piece of the picture. Kuwait’s human rights organizations refer to the country’s commitment to CEDAW as part of their advocacy. These domestic advocacy groups have participated directly in CEDAW’s monitoring by submitting shadow reports directly to the CEDAW Committee alongside a number of international human rights advocacy organizations and networks (such as Musawah, the International Disability Alliance, and Human Rights Watch) to supplement the government’s 2010 and 2015 CEDAW reports. The Kuwait Society for Human Rights (KSHR) noted in its 2011 Shadow Report a number of areas of law requiring reform to comply with CEDAW, for example, arguing that “Article 29 of Kuwaiti Constitution states ‘All people are equal in human dignity, and in public rights and duties, without distinction as to race, origin, language or religion.’ But, the Kuwaiti Penal Code does not include any article to criminalize and punish those [who] practice discrimination based on gender.”(Kuwait Society for Human Rights 2011) The Kuwait Society for the Basic Evaluators of Human Rights (KABEHR) used its shadow report in 2015 to urge the government to “necessarily publicize” the CEDAW report and its comments to “improve the public awareness of CEDAW” to help advance women’s rights in Kuwait.(Kuwaiti Society for the Basic Evaluators of Human Rights 2015) In this way, CEDAW has been a specific tool that local and international human rights groups use to promote women’s rights agendas in Kuwait, at times directly engaging with the Convention through shadow reporting to call for government reform and action.

This section has demonstrated that CEDAW is a part of a broader story of domestic change in Kuwait. The question remaining to be explored is the degree to which CEDAW has been a factor linked to these changes. I will now argue that the enhancement of women’s rights in Kuwait, partial though it has been, has also been supported by the increased framing of women’s rights issues as a fight against “discrimination” alongside the increased relevance of CEDAW across both conservative and liberal voices in Kuwait. This is demonstrated in analysis of a prominent Kuwaiti newspaper in the section that follows.

The Terminology of “Discrimination” and Reference to CEDAW in Al-Anba Women’s Rights Reporting

The terminology of preventing “discrimination” (tamyīz) as it relates to the rights of women is just one formulation of language used in contemporary women’s rights advocacy in Kuwait (other formulations include terminology of musawah, equality or of haqq, rights). It is telling that Massouma Al Mubarak, female member of the royal family who has been a minister and member of parliament, in 2005 saying “discrimination [against women] cannot continue….,” going on to mention the “good intentions of the State’s political leadership” and that “the laws against discrimination of women must be supported by all.” (Gulf News (translation)/Al-Anba, 2005). This excerpt illustrates a tension in play during the period reviewed in this paper—while some focused on the implementation of existing laws, others argued for more reforms and legal changes. I argue that the concept and terminology of non-discrimination as it relates to gender is gaining in prominence in Kuwait’s press reporting on women’s rights across political elites in Kuwait—employed both by more conservative voices or those aligned with those in power to suggest more minor efforts to support equality, as well as employed by more progressive advocates in favor of substantial legal reform and change, which may be correlated with the ratification of CEDAW and related global human rights activism. The terminology of non-discrimination is increasingly used by government officials, Islamists, and liberal activists alike in Kuwait in the context of women’s rights activism. It is used in Kuwait to discuss women’s rights as a general concept embedded in related discourses on “rights” and “equality,” and also has particular usage in the press coverage most prominently related to women’s political participation, equal rights in marriage, and the elimination of other discriminatory areas of law such as that of the labor law and in criminal law.

I illustrate that the use of the term “discrimination” (tamyīz) as it relates to the rights of women in these areas has been increasing in Al-Anba articles particularly in the period between 2006 and 2010, and also suggest that this has been explicitly linked to the CEDAW as illustrated by an increase in articles directly mentioning CEDAW. Importantly, the articles analyzed where an increase in this terminology is observed were published after Kuwait’s National Assembly approved a new press and publication law in 2006 (Kuwaiti Law No. 3 of 2006). The new law “responded to civil society pressures” for increased freedom of the press, easing restrictions on licenses and preventing the government from what previously were simple avenues for shutting down media, ending a “de facto monopoly” of the government on the private dailies in Kuwait (Selbik 2011, pp. 477–496; 477). After the 2006 changes to the law, Arabic language dailies grew in number, reshaping the media landscape in Kuwait and, arguably, expanding the political space for more robust reporting on human rights in Kuwait by way of ensuring greater freedom of the press.

Al-Anba was specifically selected as one of the widely read Arabic language daily newspapers in Kuwait and also selected for its moderate, slightly conservative, and pro-government stance. It was selected to help illustrate change among the more conservative voices in Kuwait not to exclude other perspectives and papers that would also be useful for consideration (see section on “future research”). In 2006, Al-Anba was “one of the most widely read newspaper(s) in Kuwait” and was labeled in 2012 as one of Kuwait’s “top three” newspapers. Other widely read daily newspapers in Kuwait are Al-Qabas, Al-Watan, Al-Siyassah, and al-Rai al-Am, as well as a number of weekly and periodical magazines and newspapers (Wheeler 2006, p. 80). Al-Anba was launched in 1976 and is owned by Khalid al-Marzouq, an elite businessman. The articles in the newspaper range from more neutral reporting on news and events, to interview-based profiles of individuals and organizations, to op-ed style opinion pieces on political and social issues. Al-Anba is sometimes described as “conservative” and somewhat “pro-government.”Footnote 9 Other top Arabic dailies such as Al-Qabas and Al-Siyassah have a more liberal stance and often cover the activities of liberal women’s groups, while Islamist women’s activities are covered more extensively in Al-Anba and Al-Watan (Al-Mughni 2005).

I searched Al-Anba’s online archive of newspaper reports for articles containing the terminology of discrimination (tamyīz) addressing the rights of women and identified an increase in number of articles using this language in relation to women’s rights in Kuwait since 2006. I then searched these articles for whether or not they directly mention CEDAW itself, observing an increase in these articles directly discussing CEDAW as well. Not all articles were supportive of CEDAW and its principles. These articles were also analyzed for their topics and angle, to gauge how CEDAW and the vocabulary of non-discrimination are used in the context of this reporting.

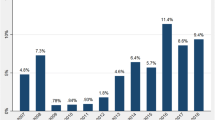

The findings firstly reveal a clear increase in the usage of the phrase al-tamyīz or close variations) in Al-Anba articles supportive of reforms to advance women’s rights particularly between the period of 2006–2010 to advocate for reforms in Kuwait. In 2006, no articles were identified using the terminology of non-discrimination in reporting on women’s issues, and in 2007, two articles were identified that used this term. The first was a July 2007 report on a group of former female candidates for the national assembly calling on government to reconsider the labor law in the private sector to stop discrimination on the hours and roles (tamyīz) in which women can work, and the second was an article reporting research from by a legal firm indicating the nature of gender discriminatory laws across a number of legal areas in Kuwait.(Al-Anba2007a, b) The July 2007 article, for example, discussed the Labor Law as clearly a case of “discrimination against women” and condemned the National Assembly for failing in its duty to “defend women’s rights” and “eliminate discrimination” (employing the terminologies and concepts of rights and non-discrimination somewhat interchangeably).

In 2008, the number increased—five articles used the term in discussing women’s issues. Most of these 2008 articles similarly mention discrimination in articles calling for reform to law, prominently around women’s rights in the family and women’s political representation, although one simply mentions the discrimination in a report that praises the government for upholding the rights of women and praises it for preventing discrimination. (Al-Anba2008) In one case, an article applauded Kuwait’s leadership in the Gulf through its work to comply with all international conventions, and the “significant progress” experienced by Gulf women. In another, the “working hours for women” were reported to raise “suspicion of discrimination.” In the same article, the language of “rights” (haqq) and “equality” (musawah) is also employed to discuss more generally the issues of social justice, but the terminology of “discrimination” is used a more specific concept to discuss the matter of inequality in employment law and practice. By 2009, 18 articles discussed discrimination against women, some praising the government, for example, for its commitment to CEDAW by fighting discrimination in the reform to the 2009 passport law, but more calling for reform to prevent and eliminate discrimination against women and uphold more equal rights. For example, an October 2009 article continued discussion on the importance of reforming labor law to remove restrictions on the hours and roles in which women can work to counter discrimination against women, reflecting ongoing debates in this time surrounding reforms to the private sector labor law in Kuwait framed as an issue of “discrimination” requiring redress.(Al-Anba2009a) This trend continued, as by 2010, the number of articles referring to discrimination against women increased yet again to 22. The topics and content in these growing numbers of press stories on gender issues remained somewhat similar, but coverage on the concept of discrimination against other groups, notably the disabled, also increased during this period—“discrimination” against all persons including those protected under UN frameworks (the disabled, women, and racial minorities) is a framing of growing prominence globally, and the evidence suggests similar trends in the coverage contained in Al-Anba.Footnote 10 This increase in the use of the term suggests that as a term itself, “discrimination” is increasingly used in reporting in the paper as a framing for articles calling for greater rights and freedoms for citizens across Kuwait, not just in the area of women’s rights.

The second grouping of findings indicates that the CEDAW itself is also increasingly mentioned in Al-Anba articles in the period following the observed increase in the terminology of non-discrimination against women. This indicates that increasing use of this terminology of CEDAW in local vernacular is correlated with growing significance of the CEDAW, but that this process is gradual and related to the importance of broader vernacularization of language of non-discrimination in Kuwait as it relates to women’s rights issues. Only one July 2007 Al-Anba article mentioned CEDAW, as discussed above, reporting on activists calling on the government to reform the code because it is discriminatory, and also because it violates Kuwait’s own commitment to the CEDAW.(Al-Anba2007c) CEDAW was only directly mentioned in Al-Anba next in 2009, in an article discussing the rights of citizenship particularly of the disabled including disabled women, loosely connecting the issue to Kuwait’s broader obligations under international law, including the ICESR, the ICCPR, the CERD, and the CEDAW.(Al-Anba2009b) By 2010, the number of articles mentioning CEDAW increased to eight. Several of these articles mention the CEDAW in neutral articles reporting on Kuwait’s commitments, and yet several of these 2010 articles praise the government for upholding commitments to the Convention, and at least two mention CEDAW as part of broader reporting on calls for domestic reform to improve women’s political representation and reform personal status, criminal law, and other areas of law discriminating against women including upholding the rights of the Bidun community. As an example of using CEDAW in calls for reform, an October 2010 article discusses lawyer Najla Al-Naqi’s call for a law to help protect against sexual harassment in universities, claiming several laws and practices in Kuwait violate Kuwait’s commitments to the CEDAW. (Al-Anba2010)

Notably, however, there are exceptions in which the concept of non-discrimination as a global norm and as enshrined in the CEDAW has also been discussed in Al-Anba in a negative light in articles criticizing the United Nations and the Convention. For example, in a June 2011 article reporting on the meeting of the Women’s Committee of the League of Islamic Scholars of the GCC states, a professor Amina Al-Jaber is quoted as criticizing the CEDAW and the broader United Nations organizations as being harmful to Islam and contrary to Sharia. (Al-Anba2011) Over the period studied, three articles raised some negative views criticizing CEDAW and its potential pitfalls for Kuwaiti society as a harmful influence, two of which were focused on the problem of “positive discrimination” and possible harms to men, suggesting a degree of pushback against the women’s rights agenda (Table 1).

Conclusions: Towards New Understandings of Impact

Through the analysis presented on reporting in Al-Anba, women’s rights discussions in Kuwait sometimes incorporate a global women’s rights language, which, among many factors, is supported by the country’s commitment as party to CEDAW. While CEDAW is not necessarily changing language directly, it must be understood as part of a broader set of factors shaping social and political discourse in Kuwait, which may, potentially, open the door for future legal and policy reform.

This analysis of articles in Al-Anba reporting which relate to women’s rights issues helps illustrate how global norms of preventing discrimination against women are localized and vernacularized in local press coverage sometimes, but not always, around the discussion of the treaty itself. The 2005 withdrawal of reservations to CEDAW spurred by Kuwait’s enfranchisement of women helped create a new space in which CEDAW was likely perceived as falling closer in line with the treaty and global women’s rights principles—the newfound presence of women in the political sphere helped, perhaps, create a context in which further discussion women’s more full achievement of equal rights might be possible, from which a growing discussion of preventing discrimination as it relates to various specific rights areas has emerged. A new area of debate has emerged since 2015 with the Abolish 153 campaign to reform Kuwait’s penal code that provides only minor sentences for women who kill female kin for committing adultery, or “honor crimes” (the campaign also aims to advocate for the abolition of similar laws across the GCC and Arab world).Footnote 11 The Abolish 153 campaign, founded by a number of Kuwaiti activists and scholars, has been successful in gaining international and domestic support, including some support from members of Kuwait’s National Assembly since 2016. The campaign has framed its advocacy partially around the CEDAW and the language of abolishing a “discriminatory law,” suggesting CEDAW’s possible role in framing these debates is important, but the law has not yet been overturned.

Despite the relatively closed civic space, CEDAW’s relevance has also been hinted at in other settings of public domestic debate on women’s issues. In May 2017, dozens of Kuwaitis gathered in the Promenade Mall in Hawally Kuwait for a “Niqashna” debate among local human rights activists over the right of Kuwaiti women to pass nationality to their children.(Al-Shuaibi 2017) This series of debates was led by Kuwaitis Mohammed Nuseibah and Nezar Al-Saleh in an effort to engage local citizens in public debate on an array of social and political issues. Those not in favor argued that the extension of the right to women “could be detrimental to the concept of Kuwaiti identity.” Arguments in support used Kuwait’s commitment to international law to support expanding rights to women, for example, Sara Al-Mutairi, president of the Constitutional Law Society in Kuwait University, who argued “Kuwait is among only 25 countries that do not grant this right. The state of Kuwait has signed all provisions of the CEDAW, but refused to sign the article granting women the right to extend citizenship to the children,” and argued the right should be extended to all women.

One interviewee for this paper working as an advisor to women’s rights associations in Kuwait suggested that the language of international human rights, particularly the framing of equality, is at times “at odds” with the authentic political discourse in Kuwait.Footnote 12 Another interviewee suggested it is comfortable and “in vogue” to work on “discrimination” issues in Kuwait, although certain issues, such as the rights of non-Kuwaitis, remain controversial.Footnote 13 While it might be more and more consistent in Kuwait to say that women “should not be discriminated against” in law, the interviewees agreed that women are still not “equal.” They may work, vote, and become educated (all areas of non-discrimination and equality covered in CEDAW), but still cannot be “head of household” (a conceptual area not covered within the text of CEDAW, but to some, central to its spirit).Footnote 14

A prominent female Kuwaiti academic interviewed suggested that tensions between Islam as a source of law in Kuwait and international human rights standards still exist.Footnote 15 To some, CEDAW’s full implementation is linked to these unresolved debates on the interpretation of Islamic principles of social order in Kuwait, drawn out in different fora depending on the area of women’s rights being considered. Regardless, as drawn out in the interviews, it seems that overall CEDAW itself is “not questioned” in Kuwait—as a ratified treaty in Kuwait “it is known to be the law.”Footnote 16 It is in the small areas of its implementation that debates emerge rather than in the idea of its application in general, which most parties when pressed would agree to in principle (notwithstanding some conservative opposition which remains empowered across Kuwait’s public and religious elite). It is increasingly more common, however, for most public officials to play lip service to support for the CEDAW and its core concepts, and few express a resistance to it in principle.

Future research to build on this should consider these questions across longer time periods, in other newspapers. Research should consider other Arabic daily newspapers with different political slants and readerships, such as more liberal papers including Al-Qabas and Al-Rai Al-Am. Other media (including social media, TV, radio, magazines, and other channels) would also be useful to analyze to broaden the findings across a range of CEDAW concepts to understand the extent to which they may be becoming adopted in local debates, including the ways in which they may be prompting resistance.

Given the findings in this article on the nature of women’s rights discussions in Al-Anba, it would be useful to trace how local advocacy efforts have galvanized CEDAW and international women’s rights norms to frame their domestic human rights advocacy around specific issues and topics of law and policy, and how these may apply differently depending on the topic. For example, it seems clear that efforts to pursue “non-discrimination” may take on a different tone from efforts framed around concepts of “equality.” There are also specific issues as they relate to CEDAW norms in the Islamic legal system. It would be useful for future research to consider these specific areas in the legal system and how advocates might frame arguments about women’s rights that adapt international human rights concepts to uniquely fit in local understandings of Islam and human rights.

It would be useful to consider the ways in which discrimination as a legal concept across various UN human rights conventions including the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD), and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) is applied in local human rights discourse including on press converge on rights issues across Arab signatory states beyond the term’s relevance to debates on the rights of women. Non-discrimination is also used in Kuwait to discuss a range of other rights areas, such as the rights of racial and national minorities and the rights of children and the disabled. Preliminary scoping of more recent articles in 2016 and 2017 in Al-Anba suggests that the treaty still maintains at least some continued relevance in local press coverage on women’s issues. Further research could consider these trends up to present day across the various areas discussed above and could explore the links between the language used in women’s rights reporting and trends in domestic politics. Although its direct impact on any legal and policy change is difficult to measure, as this discussion indicates, international human rights instruments including the CEDAW are certainly a piece of the landscape worthy of further scholarly analysis in Kuwait and across the wider GCC.

Notes

For example, in the human rights CIRI database measuring annual records of governments’ respect for a number of internationally recognized human rights areas, Saudi Arabia’s CIRI “torture” rating has not significantly improved since ratification of the UN Convention Against Torture (CAT) in 1997 (in 1997, the rating was 0 (frequently practiced), and the latest figure (2011) is also 0 (frequently practiced), although this rating slightly improved to 1 (occasionally practiced) in several years in between). In another example, when Bahrain ratified CEDAW in 2002, its CIRI rating for women’s economic participation was 1 (moderate discrimination), and this rating has vacillated between 1 and 2 in available data since then (a slight improvement of some rights with effective legal protections), more frequently at 1, indicating no steady improvement in practices following ratification. CIRI database available at http://www.humanrightsdata.com/. Similarly, Freedom House’s “freedom scores” for GCC states measuring political rights and civil liberties (which evaluate freedoms of expression, association, and belief, as well as respect for the rights of minorities and women) relevant to provisions of the human rights conventions ratified in the GCC states including the ICCPR and CEDAW have stayed relatively consistent over the past three decades at “not free,” with the exception of Kuwait at “partly free,” suggesting minimal impact of the ratification of relevant human rights treaties. Freedom House scores available at https://freedomhouse.org.

Also see critique of human rights law with the argument that despite growing ratification of human rights treaties, there has been no significant decrease in human rights abuse in Eric Posner (2014) The Twilight of Human Rights Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Amitav Acharya has noted that norm localization and “vernacularization” are similar terms, explaining “Some scholars prefer the term ‘vernacularization’ to describe the transmission of ideas and norms from one context to another” and considers “vernacularization to be similar to constitutive localization.” Debates remain open, he explains, as to the key actors in these processes, as scholars take different approaches as to which agents to focus on in tracing how norms localize. Amitav Acharya (2018) Constructing Global Order: Agency and Change in World Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 58.

CEDAW: reservations. Available at http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/reservations-country.htm

Oman’s reservation to CEDAW: Oman reserves to “All provisions of the Convention not in accordance with the provisions of the Islamic sharia and legislation in force in the Sultanate of Oman.”

Kuwait: reservations, understandings, and declarations. Available at http://www.bayefsky.com/html/kuwait_t2_cedaw.php.

Interview with female Kuwaiti political advisor, London UK, 15 October 2019.

Ibid.

See descriptions of Al Anba’s political slant in Selbik (2011), p. 482, and New York Times (1990) “Kuwait Vote Seen as Essential to Democracy,” 10 June. Available at http://www.nytimes.com/1990/06/10/world/kuwait-vote-seen-as-essential-to-democracy.html.

Note that the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CPRD) entered at the UN in 2006, but Kuwait did not accede the convention until August 2013 (see UN Treaty database, https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/TreatyBodyExternal/Treaty.aspx?CountryID=92&Lang=EN).

See information on Kuwait’s Abolish 153 campaign in “About us” at www.abolish153.org.

Interview with Kuwaiti advisor to civil society organizations, by phone, 15 October 2019.

Interview with female Kuwaiti political advisor, London UK, 15 October 2019.

Ibid.

Interview with female Kuwaiti academic by phone, 10 November, 2020.

Ibid.

References

Abbott, Keohane, Moravcsik, Slaughter and Snidal (2000) The Concept of Legalization. International Organization 54:3, 401–419.

Abiad N (2008) Sharia, Muslim States and International Human Rights Treaty Obligations: A Comparative Study. London: British Institute of International and Comparative Law.

Acharya A (2004) How Ideas Spread: Whose Norms Matter? Norm Localization and Institutional Change in Asian Regionalism, International Organization, 58; 2Spring:239-275.

Acharya A (2018) Constructing Global Order: Agency and Change in World Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Al-Anba (2007a) “Shabakat al-mar’ah tunāshid al-qiyādah al-siyāsiyyah radd al-ta‘dīlāt ‘alā qānūn ‘amal al-nisā’” [The Women’s Network Implores the Political Leadership to Reject the Amendments to the Women’s Labor Code] 2 July. Available at http://www.alanba.com.kw/ar/kuwait-news/13357/02-07-2007-شبكة-المراة-تناشد-القيادة-السياسية-رد-التعديلات-على-قانون-عمل-النساء

Al-Anba (2007b) “Al-Naqī: Al-Tashrī‘āt lā tazāl taḥmil al-kathīr min jawānib al-tamyīz ḍidd al-mar’ah al-Kuwaytiyyah” [Al-Naqi: Legislation Still Contains Many Aspects of Discrimination Against Kuwaiti Women] 4 August. Available at http://www.alanba.com.kw/ar/kuwait-news/14809/04-08-2007-النقي-التشريعات-تزال-تحمل-الكثير-جوانب-التمييز-ضد-المراة-الكويتية

Al-Anba (2007c) “Shabakat al-mar’ah tunāshid al-qiyādah al-siyāsiyyah radd al-ta‘dīlāt ‘alā qānūn ‘amal al-nisā’” [The Women’s Network Implores the Political Leadership to Reject the Amendments to the Women’s Labor Code] 2 July. Available at http://www.alanba.com.kw/ar/kuwait-news/13357/02-07-2007-شبكة-المراة-تناشد-القيادة-السياسية-رد-التعديلات-على-قانون-عمل-النساء

Al-Anba (2008) “2008 ‘ām ‘ālamī li-al-mar’ah al-khalījiyyah wa-al-Kuwaytiyyāt fī al-muqaddimah” [2008 is a Women’s Year for Gulf Women, and Kuwaiti Women are at the Forefront] 21 January. Available at http://www.alanba.com.kw/ar/kuwait-news/22183/21-01-2008-عام-عالمي-للمراة-الخليجية-والكويتيات-المقدمة

Al-Anba (2009a) “Ta‘dīlāt ghurfat al-tijārah ‘alā qānūn al-‘amal fī al-qiṭā‘al-ahlī tataḍamman mulāḥaẓāt ‘alā 16 māddah min al-qānūn” [The Chamber of Commerce’s Amendments to the Private Sector Labor Code Contain Remarks on 16 Articles of the Code] 5 October. Available at http://www.alanba.com.kw/ar/kuwait-news/parliament/69410/05-10-2009-تعديلات-غرفة-التجارة-على-قانون-العمل-القطاع-الاهلي-تتضمن-ملاحظات-على-مادة-القانون

Al-Anba (2009b) “‘Al-Khārijiyyah’ tarfuḍ wujūb manḥ al-jinsiyyah li-al-mu‘āq: haqq siyādī li-al-dawlah lā yattafiq ma‘a qānūn al-jinsiyyah” [The Ministry of Foreign Affairs Rejects Obligation to Grant Citizenship to the Disabled: A Sovereign Right of the State Inconsistent with Nationality Law] 26 July. Available at http://www.alanba.com.kw/ar/kuwait-news/58641/26-07-2009-الخارجية-ترفض-وجوب-منح-الجنسية-للمعاق-حق-سيادي-للدولة-ولا-يتفق-قانون-الجنسية

Al-Anba (2010) “Al-Naqī: Nuṭālib bi-sann qānūn li-al-taḥarrush al-jinsī wa-tawḥīd nisab ba‘ḍ al-kulliyyāt al-‘ilmiyyah” [Al-Naqi: We Call for a Law Against Sexual Harassment and for Gender Parity at Some Academic Institutions] 29 October. Available at http://www.alanba.com.kw/ar/kuwait-news/146707/29-10-2010-النقي-نطالب-بسن-قانون-للتحرش-الجنسي-وتوحيد-نسب-بعض-الكليات-العلمية

Al-Anba (2011) “Al-Jābir: ‘Sīdāw’ tata‘āraḍ ma‘a al-Sharī‘ah wa-qiyamihā wa-mabādi’ihā al-samḥah” [Al-Jaber: The CEDAW Treaty is Contrary to Sharia and its Benevolent Values and Principles] 6 June. Available at http://www.alanba.com.kw/ar/kuwait-news/201899/06-06-2011-الجابر-اتفاقية-سيداو-تتعارض-الشريعة-وقيمها-ومبادئها-السمحة

Al-Mekaimi H (2008) Kuwaiti Women’s Tepid Political Awakening, Arab Insight, 2.1: 53–59.

Al-Mughni H (2005) Kuwait in Sameena Nazir and Leigh Tomppert (eds.) Women’s Rights in the Middle East and North Africa: Citizenship and Justice. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Al-Mughni H (2010) The Rise of Islamic Feminism in Kuwait Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerranée [Review of Muslim Worlds and the Mediterranean], December. 128: 167–182.

Athoob Al-Shuaibi (2017) “Should Kuwaiti Women be Able to Pass Nationality to their Children? - The Niqashna Debates,” March 30, Kuwait Times. Available at http://news.kuwaittimes.net/website/kuwaiti-women-able-pass-nationality-children-niqashna-debates/.

Ban P, Fouirnaies A, Hall A and Snyder J (2019) How Newspaper Reveal Political Power, Political Science 844 Research and Methods, 7.4: 661–678.

Barnett M and Finnemore M (2004) “Rules for the World: International Organizations in Global Politics.” Ithaca: Cornell UP.

CEDAW Committee (2004) Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 18 of the Convention of Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, Kuwait: CEDAW/C/KWT/3–4.

CEDAW Committee (2019). Concluding observations on the fifth periodic report of Kuwait. CEDAW/C/KWT/CO/5/Add.1

Darraj SM (2010) The Universal Declaration of Human Rights. New York: Infobase Publishing

De Waal E and Schoenbach K (2008) Presentation Style and Beyond: How Print Newspapers and Online News Expand Awareness of Public Affairs Issues, Mass Communications and Society, 11, 2:161–176.

Hassan M. Fattah (2005) “Kuwait Grants Political Rights to Its Women.” 17 May. The New York Times. Available at http://www.nytimes.com/2005/05/17/world/middleeast/kuwait-grants-political-rights-to-its-women.html?_r=0.

Finnemore M and Sikkink K (1998) International Norm Dynamics and Political Change, International Organization, 52.4:887–917.

Goldsmith J and Posner E (2005) The Limits of International Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hafner-Burton E, Victor D and Lupu L (2012) Political Science Research on International Law: The State of the Field. The American Journal of International Law. 106.1:47–97.

Keck and Sikkink (1999) The Socialization of Human Rights Norms in Stephen Ropp and Kathryn Sikkink, The Power of Human Rights. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Koh CY, Wee K, Goh C and Yeoh B (2017) Cultural Mediation Through Vernacularization: Framing Rights Claims Through the Day-off Campaign for Migrant Domestic Workers in Singapore, International Migration, 55, 3:89–104.

Kuwait Society for Human Rights (2011) “Shadow Report of the Kuwait Society for Human Rights,” p. 1.

Kuwaiti Society for the Basic Evaluators of Human Rights (2015) “Shadow Report on the Implementation of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women by the State of Kuwait,” p. 8.

Levitt P and Merry SE (2009) Vernacularization on the Ground: Local Uses of Global Women’s Rights in Peru, China, India and the United States, Global Networks, 9,4:441–461.

Levitt, P, Merry SE, Alayza R and Meza MC (2008) Vernacularization in Action: Combining Global and Local Ideas About Women’s Rights in Peru (draft version), Working Paper, The Graduate Institute Geneva.

Maktabi R (2016) Female Citizenship and Family Law in Kuwait and Qatar: Globalization and Pressures for Reform in Two Rentier States. Nidaba, 1:20–34.

Mohamed Olimat (2011) “Women and the Kuwaiti National Assembly,” Journal of International Women’s Studies, March. Vol. 12, No. 3, pp. 76–95.

Selbik K (2011) Elite Rivalry in a Semi-Democracy: The Kuwaiti Press Scene, Middle Eastern Studies, 47, 3:477–496.

Shalaby M (2015) Women’s Political Representation in Kuwait: An Untold Story. Rice University. Report. Baker Institute for Public Policy.

Shultziner D and Tetreault MA (2011) Paradoxes of Democratic Progress in Kuwait: The Case of the Kuwaiti Women’s Rights Movement, Muslim World Journal of Human Rights, 7,2:1–25.

Simmons S (2008) Mobilizing for Human Rights: International Law in Domestic Politics. New York: Cambridge UP.

Wheeler D (2006) The Internet in the Middle East: Global Expectations and Local Imaginations in Kuwait. New York: SUNY Press, p. 80 and Anti-Defamation League (2012) “Arab Media Review,” January–June, Available at https://www.adl.org/sites/default/files/documents/assets/pdf/anti-semitism/Arab-Media-Review-January-June-2012.pdf. Accessed 15 March 2018.

Wiener A (2004) “Contested Compliance: Interventions on the Normative Structure of World Politics.” European Journal of International Relations. 10 (2):189–234.

Wiener A (2007) “Contested Meanings of Norms: A Research Framework.” Comparative European Politics. 1(5): 1–17.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

George, R. The Impact of International Human Rights Law Ratification on Local Discourses on Rights: the Case of CEDAW in Al-Anba Reporting in Kuwait. Hum Rights Rev 21, 43–64 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12142-019-00578-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12142-019-00578-6