Abstract

In this paper, I argue that the phenomenon of faultless disagreement for predicates of taste may be fruitfully explained by appealing to the vagueness of predicates of taste and the epistemicist reading of vagueness as defended by Timothy Williamson (1994). I begin by arguing that this position is better suited to explain both the “faultless” and “disagreement” intuition. The first is explained here by appealing to the necessary ignorance of the predicate’s boundaries and a plausible account of constitutive norms of taste assertions, while the second by insisting on classical, absolutist semantics for judgments containing predicates of taste. Furthermore, I analyze the arguments against the reading of taste predicates as vague based on the alleged epistemic privilege concerning one’s taste and on the lack of definite cases. Responding to these objections, I develop a plausible account of constitutive norms of taste assertions, comment on the assumed epistemic privilege concerning taste ascriptions and provide a more detailed account of sources of the vagueness of predicates of personal taste, which I dub “super-vagueness.”

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Despite the prevalence of the well-known Latin phrase, it seems that we do get sometimes into arguments on matters of taste. Also, although this old wisdom claims that such disputes, when they already happen, are irrational, we certainly do not often feel that they are when we participate in them; moreover, such disputes can be elaborate and contain a variety of reasons supporting the claim of each involved party. Consider the following conversation:

A: This chili is tasty.

B: No, it is not. It’s too sweet, not spicy enough, and certainly lacks a good amount of juicy beef.

or:

A: This movie was not fun.

B: No, it was actually. The characters were developed and the script was full of well-thought and enjoyable plot twists.

We can imagine similar exchanges to continue for a long time and become more and more elaborate, and probably, we did enter at least one of those in our lifetime. Sometimes they may end with a recognition of mutual position (It seems that we will not agree on this, but I respect your opinion), sometimes in the change of mind (You’re right, this movie was quite good actually), sometimes in violent outbursts or profound confusion. They are, however, not merely an exercise in mischievous persuasion—when engaging in them, we usually enter them with sincere intentions and hope that the arguments we make will change the mind of our interlocutor and make them retract their previous assertion.

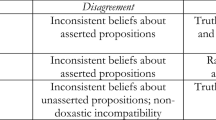

I believe that this fact is overlooked, at least in debates concerning predicates of taste and so-called faultless disagreement (Kölbel, 2004). Faultless disagreement is usually understood as arising in cases similar to the above conversational patterns (more precisely, their not-italicized part), which in turn had been thought to have profound consequences for our understanding of the semantics of predicates such as “tasty,” “fun,” or “delicious.” The debates in question are fueled by the urge to accommodate two intuitions that seemingly remain in tension: (a) the intuition that in such cases A and B are genuinely disagreeing—which seems to entail that their assertions stand in contradiction, and (b) the intuition that both A and B are entitled to saying that the movie was fun or not and none of them is at fault for, say, not thinking their assertion through or drawing it from inaccurate premises. These intuitions were usually approached in three different modes, contextualist (e.g. Schaffer, 2011; Stojanovic, 2007, 2017; Zakkou, 2019a, 2019b), relativist (e.g., Kölbel, 2004; Lasersohn, 2005, 2008, 2009; MacFarlane, 2014), and absolutist (e.g., Moltmann, 2010; Pearson, 2013; Wyatt, 2018); some also argued that the phenomenon of faultless disagreement is merely a mirage and the very concept is, at its core, self-contradictory (Iacona, 2008).

I do not intend to offer decisive arguments against the abovementioned stances nor argue that any of the abovementioned strategies are doomed to fail.Footnote 1 I will aim at showing, however, that the “vagueness” form of absolutism—the stance that calls for an objective and absolute reading of predicates of personal taste and treats these predicates as vague—had been overlooked unjustly and as such it provides a more coherent and attractive view of the meaning of taste judgments than its competitors. I will argue that the account of such predicates as vague (or rather super-vague—a term I will introduce later) along the lines of epistemic accounts of vagueness can provide us with a semantics for predicates of taste worthy of consideration and an explanation of both intuitions.

In the following, I will provide more detailed arguments for treating predicates of taste as vague and the way it could account both for the (a) disagreement and (b) faultlessness intuitions (Sections. 2 and 3). Then, I will counter two objections to this view: the first is coming from the alleged epistemic privilege of a person judging something as “tasty” or “fun” (Lasersohn, 2005, p. 656), and the second from the apparent lack of definite cases of “tasty” which is thought to be characteristic of vague predicates in general. Responding to these objections, I develop a plausible account of constitutive norms of taste assertions and comment on the assumed epistemic privilege concerning taste ascriptions (Section. 3) and a more detailed account of sources of the vagueness of predicates of personal taste, which I dub “super-vagueness” in Section. 4. For the sake of brevity, I focus exclusively on the predicate “tasty,” although I will hint at how similar analyses could be developed for other similar predicates.

2 The Vagueness of “Tasty” and the Disagreement Intuition

Ideas that seem to support the absolutist reading of predicates of personal taste may be interpreted in two ways. One tempting option, which was usually pursued by absolutists, is to read taste judgments of the form “That chili is tasty” as expressing a generic statement, true only if a normal user, or most of the ordinary users of language would judge that chili tasty (Moltmann, 2010; Pearson, 2013). These views, however, have problems with accounting for the (b) intuition—for they predict that there is an empirically verifiable fact that the chili is tasty or not (although, perhaps, it is very hard to verify—but this difficulty does not amount to impossibility), which means that either A or B is at fault. Similarly, such positions are unfit to explain the reason-giving data mentioned at the beginning. When B tried to justify why they regarded chili as not tasty or the movie to be fun, they clearly were not pointing out the statistical data or the experience of other people. The following conversation should also, I take it, be interpreted at best as a case of ad populum persuasion rather than providing actually convincing reasons:

-

A: This movie was not fun.

-

B: No, it was actually. It has a 92% audience-approval score on Rotten Tomatoes.

Another way to provide an absolutist account is to appeal to vagueness displayed by predicates of taste. Although this view had certain support in the literature (see e.g. Wyatt, 2018; Barker, 2013 for elaboration), the epistemicist route of explaining faultless disagreement had not been, to my knowledge, given any serious and detailed treatment in the literature, despite being explicitly mentioned as a possible view (although criticized) as early as in Lasersohn’s (2005) seminal discussion and later evoked by some absolutists (Barker, 2009). In the following two sections, I will first argue that there are sufficient reasons to think that predicates of taste are vague and then discuss how the epistemicist view on vagueness could provide us with a good explanation of the faultless disagreement data.

Let me start by observing that (a) and (b) intuitions seem to be also elicited by cases of disagreement over applying vague predicates. Consider the following exchange:

-

A: Wow, John is rich!

-

B: No, John is not rich. He barely affords to pay the rent in San Francisco!

Though such discussion may not be as elaborate, they similarly seem to be cases of actual disagreement over John’s wealth (a), and both A and B do not seem to be at fault for their respective evaluations if John is a borderline case of “rich” (b) (see: Wright, 2001; Odrowąż-Sypniewska, 2021). If faultless disagreement may arise in such cases, then it seems plausible that standard contextualist (indexical) or relativist responses to disagreement do not generalize well to all faultless disagreements,Footnote 2 since vague predicates are not, in the normal sense, indexical expressionsFootnote 3 or in need of a perspective-based evaluation.

But are such cases merely another species of faultless disagreement or could they be thought to be the paradigmatic examples, at least when it comes to disagreements about taste?

To put forth such a hypothesis, we need to establish whether disagreements about taste involve the use of vague predicates—in other words, whether “tasty” or “fun” is vague. A good way to test whether the predicate is vague is to check whether they are sensitive to the sorites inference, most universally thought (Bueno and Colyvan 2012) to be the defining feature of vague predicates, regardless of whether we take into account a particular perspective. When disagreeing about whether chili is tasty, B provided several reasons for why it is not: namely, that it is (a) too sweet, (b) not spicy enough, and (c) not beefy enough. Let us assume for a moment that A, thinking that the chili is in fact tasty, disagrees with B on these grounds and finds the chili tasty precisely because it is just sweet, spicy, and beefy enough in their evaluation. Given that all of these evaluations contain, in effect, ascriptions of vague predicates to the chili, we might expect that by utilizing their vagueness, we could construct the sorites argument for “tasty.” Consider now only one of these dimensions, say, spiciness, and assume that we add bit by bit a grain of cayenne spice to the dish, while the other parameters are set at a moderate level. It seems clear that for A, the chili containing m grains of cayenne (the actual number of grains in the chili) is tasty, and adding a minuscular grain of spice to the dish would not change our overall evaluation of tastiness:

-

(1)

The chili containing m grains of cayenne is tasty

-

(2)

If a chili containing n grains of cayenne is tasty, then a chili containing n + 1 grains of cayenne is tasty

Accepting (1) and (2) straightforwardly leads us to reproduce the sorites reasoning for “tasty.” We might think of a bizarre experiment, in which we place two chilis judged respectively tasty and not tasty by A, and a number of similar plates of chili between them, each with a slight and undetectable difference in the abovementioned parameters. By sorites reasoning mentioned above, we should conclude that both chilis are tasty to A or that they both are not.

This observation leads to the following hypothesis: irresolvable disputes about taste are, in effect, a species of faultless disagreements concerning the application of a vague predicate.Footnote 4 But may this observation suffice to explain the intuitions (a) and (b)? Of course, merely pointing out an analogy will not suffice by itself: for we have yet no independent reason to think that faultless disagreement intuition is anyhow generated by the vagueness of the predicates used. However, an independently plausible and widely defended theory of vagueness, epistemicism, may, by describing the mechanisms underlying vagueness, provide us with some tools to understand the phenomenon of faultless disagreement about taste. Or so I will argue.

Let us first note that by assuming an epistemic view of vagueness along with its absolutist semantics and treating predicates of taste as vague, the disagreement intuition (a) is straightforwardly dealt with. According to epistemicists, vague predicates have sharply delineated, albeit unknowable boundaries. Unlike contextualists or those willing to apply non-classical logic to sentences containing vague predicates (super- and subvaluationists), the epistemicist claims that the sentence “a is F,” where F is a vague predicate, is absolutely true or false—but we necessarily fail to know which. Since the statement “That chili is tasty” is absolutely true or false, then A’s and B’s assertions stand in a genuine semantic contradiction; only one of them speaks truly.

This straightforward understanding of a contradiction between what is said by both speakers stands in sharp contrast to ways in which the (a) intuition is proposed to be dealt with by contextualists and relativists. Since the founding texts of Lasersohn and Kölbel, the contextualist approach, which analyzes assertions containing predicates of taste of the form “x is F” as meaning “x is F (for A)” (A being the agent of the context or some contextually salient judge), had been thought to have problems with accounting for the disagreement intuition. For if two speakers are faultless and express “x is (not) F” from their respective perspectives, they are expressing two propositions that are not mutually contradictory (since one speaker states that x is F for A, while the other that x is not F for B). As noted however by, e.g., Isidora Stojanovic (2007, 2017, p. 10–11), a relativist approach only puts the problem one step further. If the fact that taste judgments have relativist semantics is a piece of common knowledge among speakers (as we would expect if this fact were to account for our semantic intuitions), then engaging in disagreement is in no way more rational. Since we all presumably know that in this context the proposition that x is F should be evaluated according to some (usually egocentric) perspective, disagreeing would not be regarded as directly contradicting your interlocutor but rather introducing some other evaluative perspective into the conversation. There is then simply no point in disagreeing, let alone trying to convince someone.Footnote 5

Contextualists may, of course, argue that (a) intuition should be modeled not at the level of contradiction in semantic content but as a contradiction or a conflict at the level of incompatible beliefs or attitudes (e.g., Huvenes, 2014; Zouhar, 2018) or presuppositions concerning relevant standards the speakers imply are in place (Silk, 2016; Zakkou, 2019a, 2019b). Though I shall not offer anything close to a knock-down argument against these or any other possible extensions of either contextualism or relativism, they seem to be nevertheless ill-equipped for the task of explaining why we engage in providing reasons for our evaluations of taste once we recognize that our opinions diverge. If either the contextual or relativist nature of taste judgments were to be publicly available, it would seem infertile to provide non-practical, epistemic reasons for our evaluation to change someone else’s, since their perspective may be essentially different from ours and hence—the truth of what they say would remain secure. Such disputes would be exercises in essentially irrational persuasion, for, given the non-absolutist semantics of predicates of taste, there is no non-practical reason for the compatibility of attitudes to be achieved. If B disagrees with A about the taste of chili and justifies their position by providing reasons transparently concerning the way the chili tastes, it is superficial to claim that in fact such reasons are meant only to change conversational standard of tastiness or influence other person’s non-doxastic attitude. Although it is certainly possible that our taste judgments have some justification under the contextual or relativist reading of taste predicates, this justification is essentially private and therefore probably not persuasive for other people. But if this were the case—then why do we engage in such disputes so often? The epistemicist’s answer is clear in this respect: we argue about taste because there is something to argue about after all. The epistemicist holds that the reasons for calling something “tasty” or “fun” are uniform and public; therefore, reason-giving is rational, even if not always effective. Of course, it does not mean that the only aim of such reason-providing behavior is to change their interlocutor’s mind: we may provide such reasons to make our assertion immune to further criticism or even simply elaborately show appreciation or contempt. The point here is weaker: given that we sometimes do try to influence other people’s minds by providing such reasons and we agree that it is an important feature of the discourse employing predicates of taste, we should think of the reasons we provide in such discussions as publicly available and objective, not inherently private in the way the contextualist and relativist positions invite us to.

3 Williamson’s Epistemicism, Norms of Taste Assertions, and the Faultlessness Intuition

“That’s all fine”—you might say—“but you still didn’t provide any account of faultlessness. Surely, A and B are both entitled to their opinion and hence it would be wrong to simply picture one of them as absolutely right and the other as absolutely wrong.”

This objection, as I have shown above, is problematic for the generic absolutists; can epistemicists provide a plausible account? I think that they can, by appealing to the unknowability of the boundaries of predicates of taste, and in effect argue for the epistemic interpretation of faultlessness. Epistemicists argue that borderline cases of vague predicates are cases of necessary ignorance—that despite there being an objective threshold, we are ignorant of it. This ignorance accounts for the fact that disputes on the matters of taste, as well as disputes over borderline cases of vague predicates, are empirically or conceptually irresolvable—the righteousness of one’s position cannot be therefore established using empirical measurement or as an analytic truth. Though one of the speakers says something true, while another something false, neither of them should be regarded as being at fault because neither of them might improve the epistemic position they hold—they may both be “optimally justified in holding their beliefs” (Hu, 2020, p. 2617). Against the standard understanding of faultlessness, according to which disagreement is faultless only if neither of the disagreeing parties believes something false, the epistemic account weakens this condition to the effect that neither of the parties could know that they are wrong. Moreover, it quite naturally explicates the intuition according to which “being at fault” should apply first and foremost to the speaker’s relation to the believed proposition rather than the proposition itself: they are at fault if they might have improved, faultless otherwise.

This interpretation (proposed also by Hills, 2013; Hu, 2020; Schafer, 2011) might invite an objection, for the sense of “faultlessness” employed in the characterization of faultless disagreement is usually thought to hold only of paradigmatically subjective domains, while our account would predict that it is also possible in the objective ones (Eriksson and Tiozzo 2016). But the case for the essentiality of this difference seems quite weak: it may be easily explained by the fact that simply usually the disagreement in the objective domain may be resolved by “further investigation” (as Kölbel 2004, p. 59] characterizes the difference). If we accept the epistemicist approach to vagueness or, more generally, accept that certain facts in the objective domain may be inherently unknowable despite our belief-forming mechanisms being reliable, we have no reason to suspect that there is a difference of substance rather than of degree between these domains.Footnote 6 The epistemic interpretation seems at least equally well-suited to explain the (b) intuition as its standard interpretation without giving up the absolutist semantics.

But, given our underprivileged epistemic position, shouldn’t we then remain agnostic on matters of taste? And, by Williamson’s popular knowledge account of assertion (2000, p. 243), we should refrain from judging or asserting that any chili is tasty or awful as it cannot be known? I think that such a conclusion could only be substantiated by a very strong reading of the knowledge norms of belief and assertion, and hence, being at fault. For even if such norms are true of most beliefs and assertions, in cases of perceptual, aesthetic, or religious assertions and beliefs we do seem to revise our standards and many have argued for such content-specific norms.Footnote 7 As an example of a content-specific constraint that does not apply to other assertions, think of a person judging “The chili is tasty” or “The movie is fun” without actually tasting the chili or seeing the movie (Pearson, 2013, p. 117). A natural reaction is that such a person has no right to claim that, even if they got such information from the testimony of a trusted gourmet or film critic. As noted as early as in Kant’s “Critique of Judgement” and repeated by many aestheticians (Muelder Eaton, 2001; Schellekens, 2006), similar seems to apply to judgments of beauty (for an elaboration of this Kantian view in the form of a norm of assertion, see: Collins, 2021). It is plausible then that some norm of perceptual justification applies in cases of taste or enjoyment.

Moreover, as we saw in the first two dialog examples, such assertions can be, and often are, challenged by offering counter-reasons. It would be strange if A responded to B’s challenge in the following manner:

-

A: You’re right, the chili is too sweet, not spicy enough, etc. In fact, it has no positive qualities at all. But it’s still tasty.

My intuition is that we could regard A as being at fault in this situation since they cannot anyhow justify or explain the basis for their judgment—that is to defend their assertion when challenged.Footnote 8 But if A responds in the following way:

A: No, I think it’s just right sweet, beefy, and spicy.

or

A: You’re right, the chili is too sweet, not spicy enough, etc. But this could be forgiven; it’s tasty because it has other unique qualities such as a unique balance of sourness and saltiness.

they seem to be genuinely faultless. All of this suggests that in cases of truly faultless disagreement both speakers need to possess some justification or warrant for their assertion. What they might disagree on here is rather which part of qualitative evidence they have is decisive for calling the chili “tasty” (e.g., sweetness or sourness) or how they evaluate the same qualities (e.g., beefiness). If they both possess justification for their claim, they seem to warrantably assert their respective judgments, and since there is nothing more they could do to improve (turn their justified belief into knowledge), they should not be regarded as being at fault. Judging or asserting something false should not put one automatically at fault—intuitively, this only should be the case if there is some detectable flaw in their reasoning, or they are guilty of a cognitive omission.

One could model the norm of assertion in question after Collins’ norm of aesthetic assertion (2021, p. 978):

(NTA) S may assert that x is tasty only if S takes pleasure in the experience of taste-related properties of x, that is not based upon idiosyncratic features or etiology of the experience, and so the judgment is to be commended universally as based upon S’s experience of x independent of all other factors peculiar to S.

I wish not to defend a specific wording of NTA in this paper, but rather point out, that there are certain normative constraints for taste judgments to be warranted, such as possessing an essentially public (that is—not idiosyncratic or peculiar to S) and first-hand gathered justification. While usually in discussions concerning taste disagreements “being at fault” is characterized as merely judging or asserting p if p is false (cf. Kölbel, 2004, pp. 60–61, Iacona, 2008, p. 287), a more natural way in which it may be captured is a failure to live up to standards set up by NTA or a similar rule in the absence of evidence that may improve one’s judgment. If we are to believe the epistemicists and theoreticians of constitutive rule accounts of assertion, then it seems plausible that some version of NTA holds for taste-related assertionsFootnote 9 and hence the faultlessness intuition is well-captured by compliance with this norm.

The prediction concerning conversational patterns exhibiting faultless disagreement is therefore that the taste judgments can be expected to be retracted when challenged insofar as they violate NTA. We are right then in criticizing others for judging something without having its first-hand experience or if they cannot provide an acceptable, non-idiosyncratic justification for their evaluation, which provides a rationale for entering taste disputes. When this does not happen and the interlocutor provides such a justification that cannot be questioned further, the dispute ends in a stalemate. We may therefore both explain the rationality of entering such discussion as a way of challenging justification behind other person’s evaluation and providing reasons for one’s taste judgment as a way of defending one’s position, as well as the fact that many such debates are inconclusive if the defense proves to be effective on both sides.

One may,Footnote 10 of course, question this guiding intuition and hold that providing such reasons is perhaps common, but by no means necessary to warrant taste assertions: one may assert permissibly assert that x is tasty just because they like it. This intuition, I take it, has two different roots; first is that the one’s liking is so intrinsically intertwined with our taste judgment, that they might seem as merely two ways of describing the same phenomenon. We would almost surely never find someone asserting the following:

-

(1)

#x is tasty, but I don’t like it.

-

(2)

#I like x, but it’s not tasty.

Both (1) and (2) seem close to a contradiction. The NTA-based explanation is, however, quite well equipped to explain their absurdity and, by extension, why taste assertions go hand in hand with avowals of one’s liking. Under NTA, (1) and (2) should be both classified as analogs of Moore-paradoxical sentences (classically of the form: ‘p, but I don’t know/believe that p”), for one’s avowal or disavowal of liking x counts as a defeater for their assertion of the form “x is (not) tasty.” (1) and (2) and their kins are therefore always infelicitous and, hence, one is always committed to the avowal “I like x” if one asserts that x is tasty. Moreover, if one finds themselves to like x for non-idiosyncratic reasons—i.e., they do not take their taste sensations to be distorted or peculiar only to them—they are therefore warranted in making a taste assertion, and hence, the intuitive “because I like it” justification for taste assertion is secured. While taste judgment and liking avowal have different semantic content and justification, they go, at least in most cases, hand in hand.

However, one may still object to this and claim that one need not have any particular reason for one’s likes and find something tasty just because it’s tasty to them. In a sense, “liking” or “finding tasty” need not be robustly connected with other evaluations, contrary to what “reason-giving” conversational patterns might suggest. In effect, the theoretician supporting this objection rejects the intuition reported above, according to which when A asserts:

-

A: The chili is too sweet, not spicy enough, etc. In fact, it has no positive qualities at all. But it’s still tasty.

A’s taste assertion is still warranted simply in virtue of them liking the chili, despite they are not able to express why.

While I personally do not find such defenses intuitively persuasive, they could be, in some cases, still accommodated by NTA. The proposed norm does not explicitly demand from us to be aware of the particular qualities we find pleasant. There are cases in which the specific combination of flavors that give rise to our positive evaluation is not easily dissectible: it might be hard to say, for example, whether a particular drink is actually sweet or not, and different flavors might be easily confused (as in the case of well-known “sour”/ “bitter” confusion). Such subjects may then find themselves in the position of having a pleasurable taste experience of x without knowing what exact combination of flavors caused it. Are they still warranted in asserting that x is tasty? As such, NTA does not prevent it—at least if we adopt an externalist view of perceptual justification. One may be warranted in asserting p, despite not knowing that one is. Such assertion is perhaps careless or secondarily improper (in the terminology of DeRose 2009), yet not necessarily defective.

It seems then that the epistemicist can explain the faultlessness intuition by appealing to ignorance and postulating still relatively strong content-specific norms for taste judgments. To provide a full account, epistemicist however needs to not only claim that sharp boundaries of vague predicates are unknown but also explain why these boundaries are set the way they are while being necessarily unknowable. Here, I think, the best and the least controversial candidate for an explanatory mechanism for predicates of taste would be Williamson’s account of vagueness (1994).Footnote 11 According to Williamson, the sharp boundaries of vague predicate’s extension supervene on the overall pattern of use of such predicate in the community’s practice (Williamson, 1994, p. 211); dispositions of individual users need not match and may frequently be erroneous. Can such an explanation be applied to “tasty”? I think there is no principled reason against it. Although taste is usually regarded as intrinsically personal, there is certainly a significant influence of one’s social position, ethnic background, or upbringing on what one judges “tasty,” “fun,” “spicy,” and so forth.Footnote 12 If such sociological analyses of taste judgments are right, it should come as no surprise that patterns of use would roughly match in a given group, and hence, the overall meaning of the predicate would be established. What is worth noting is that this match extends from the mere classification to robust patterns of justification used in different communities. For example, a group of upper-class gourmets could regard a white truffle risotto tasty because of its unique balance of savory tastes, while someone less posh could justify a similar evaluation by saying it has just enough salt and the rice is not over- or undercooked. These differences in judgment between social and ethnic groups also could give us a fruitful account of truth conditions of the following commonly used sentences:

-

(A)

This chili is too spicy for Europeans, but tasty for Mexicans.

-

(B)

Casa martzu is tasty for Sardinians, but disgusting for Americans.

The truth of such sentences may be understood as specifying the relevant comparison class (and therefore a relevant pattern of use) in a similar way as the sentence “John is rich for an Alabamian but poor for an inhabitant of San Francisco”. They should not be interpreted merely as propositions made true by statistical convergence in judgment (as Moltmann or Pearson would have it) but by the fact that the extension of “tasty” or “spicy” is determined by the pattern of use in the particular community. This, according to a Williamsonian epistemicist, also extends to the idiolectic uses of predicates of taste, which allows us to account for the vagueness of egocentric ascriptions of “tasty” exhibited by the sorites reasoning exemplified above:

“You have no way of making your use of a concept on a particular occasion perfectly sensitive to your overall pattern of use, for you have no way of surveying that pattern in all its details. Since the content of the concept depends on the overall pattern, you have no way of making your use of a concept on a particular occasion perfectly sensitive to its content. Even if you did know all the details of the pattern (which you could not), you would still be ignorant of the manner in which they determined the content of the concept.” (Williamson, 1994, p. 231–232).

The content of your idiolectic concept of “tasty” depends on this view on your overall pattern of use, as the public concept depends on the pattern of use of all speakers in the community. Therefore, it is impossible not only to know whether some dish or the other is absolutely tasty but even whether it is always tasty to us.

Of course, this may seem like an unexpected result. Many philosophers engaged in the debate on faultless disagreement either tacitly or explicitly assumed that in judging something tasty one operates from a point of epistemic privilege, not ignorance. Consider the following point made by Lasersohn against a briefly-mentioned Williamsonian interpretation of “tasty”:

“[W]ith predicates of personal taste, we actually operate from a position of epistemic privilege, rather than the opposite. If you ride the roller coaster, you are in a position to speak with authority as to whether it is fun or not; if you taste the chili, you can speak with authority as to whether it is tasty. (…) Notice that this is a stronger privilege than we get even from direct observation. For example, if I see a car, I can say that it is red; but there is still the possibility that I could be in error—for example if I am color-blind. But even if I have an unusual tongue defect that makes me experience flavors differently from most people, if I try the chili and like it, it seems to me that I am justified in saying The chili is tasty.” (Lasersohn, 2005, p. 655).

Note that this point against the epistemicist’s position may be brought up by both a relativist and a contextualist about taste judgments. Both of these views do gain their intuitive support from the idea that qualities captured by predicates of taste are “personal” and intimately known by assertors—at least in cases of idiolectic uses of “tasty” or personal predicates such as “tasty to A.” Since we do feel entitled to assert taste judgments based on our liking, we tend to think that the very meaning of taste judgments or their truth evaluation conditions should mirror this perceived authority. The absolutist-epistemicist, by claiming that it is impossible to know whether something is tasty or not, therefore contradicts this commonsense intuition which is easily explained by contextualist or relativist approach.

To respond to this objection, we need to dissect the two readings of epistemic privilege. One way to interpret it is to take it to be a claim according to which the speaker’s justification for their taste assertion is epistemically privileged, i.e., one knows firmly whether one finds something tasty. This claim seems undeniably true—but is in no way contradictory to the NTA-based epistemicist explanation. NTA predicts that whenever we find something to be tasty (for non-idiosyncratic reasons), we are in a position to assert that it is. This crucial prediction explains, after all, why we find such assertions to be faultless on the epistemicist account.

Unlike Lasersohn, however, the epistemicist-absolutist rejects that this type of epistemic privilege transfers to “tastiness” itself—for one may still be wrong (though justified) in making the all-out assertion of the form “x is tasty.” We might usefully bring out this difference in the case of simple vague predicates: though one is plausibly justified in asserting “x is blue” (where x is a borderline case of “blue”) when one has a perceptual experience of blueness, their assertion still might turn out to be false. Though one is epistemically privileged in classifying their own experience and, plausibly, this fact guarantees the truth of avowals like “x is tasty to me” or “x is blue to me,” one is denied further privileged access to external qualities of tasted or perceived object. In other words—Lasersohn’s objection confuses two levels of epistemic privilege: one’s privileged access to one’s taste and privileged access to the tastiness itself. Once we assume the absolutist semantics for “tasty,” these two types of access need to be separated, and, assuming epistemicist analysis of “tasty,” speakers might be coherently granted the first and denied the other.Footnote 13

These considerations also go in line with the observation, that the intuition of faultlessness disappears when the simple taste judgments in the dialog are preceded by a knowledge operator:

-

A: I know that this chili is tasty.

-

B: No, I know that this chili is not tasty.

The intuitive reading of this dialog seems to be that “it is at most either A or B that is right, but not both. Both A and B may have grounds for maintaining the content of their knowledge claims, but at least one of them is at fault” (Moltmann, 2010, p. 210). As Friederike Moltmann notices, this fact cannot be easily accounted for by Lasersohn’s relativist semantics, since his account would predict that the A’s statement should be regarded as more-or-less truth-conditionally equivalent to the statement “I know that I like this chili,” while the preceding factive “I know” operator forces the objectivist reading. The contextualist account faces a similar problem, as “I know that the chili is tasty to A” and “I know that the chili is not tasty to B” are not contradictory. While Moltmann claims that the reading in question should be equivalent to the generic “I know that one likes the taste of this chili” (2010, p. 210–211), the conclusion offered by an epistemicist is even simpler. According to them, the problem with such disagreements is that at least one (and probably both) of the speakers has no appropriate justification to claim the knowledge of the fact that the chili is tasty, for although they may both have some justification for the content of their knowledge claim, at least one of them has no justification to treat it as knowledge-generating and, therefore, violates the associated norm of asserting the judgments of taste.

The introduction of Williamson-inspired epistemicist semantics for taste predicates allows us to combat one of the most pervasive criticisms of previous absolutist proposals. For one, as I mentioned earlier, it does not commit us to the implausible consequence of a generic form of absolutism, according to which the semantic content of an “x is tasty” judgment ought to be taken to express a generic judgment of whether the unspecified standard speaker (or most speakers, or their important subgroup, e.g., a group of ideal critics [Baker and Robson 2017]) would judge x to be tasty. While the epistemicist account also appeals to the relation between the overall pattern of taste judgments and the truth value of the respective judgment, it does so by pointing out that the extension of the predicate “tasty” is just established by such pattern without postulating that the meaning of “tasty” is just “judged as such by X.” Moreover, it provides a reason to think that the exact boundaries of this extension are unknowable and hence account for the faultlessness intuition better than these competing views. On the other hand, unlike other recent versions of absolutism, e.g., Wyatt’s (2018), it does so without postulating the difference on the level of speaker’s attitudes: the vague content of disagreeing parties’ beliefs stays the same as the semantic content of their assertions and is justified by the same class of facts, i.e., properties of flavor. Therefore, it embraces the parallel between mental and semantic content expressed by one’s taste assertion, which remains problematic for Wyatt’s position (Hîncu and Zeman 2021, pp. 1327–1328) and at the same time provides a metaphysical picture of what property “tasty” expresses and the epistemic relation between this property and the community of speakers (for objections along these lines towards Wyatt see: Zouhar, 2020).

4 Definite Cases and Super-vagueness

In this section, I will try to make my account more precise and reply to an objection that might be directed (e.g., Karczewska, 2016, p. 113–115) against the claim that “tasty” is a vague predicate. “Maybe there is some reason to believe that the predicates of taste are vague—at least for the judges themselves. But one of the defining features of vague predicates apart from susceptibility to sorites is the existence of borderline and definite cases. Everyone would rationally agree that Elon Musk is rich, but would everyone agree that some dish or the other is tasty?”.

Surely, what needs to be granted is that the cases of supposedly general agreement on taste one could think of (Everybody likes pizza!) are far less convincing than in the cases of traditional vague predicates (Everybody judges Elon Musk to be rich). Appealing to the views of the general public does not seem to be helpful, since such a survey would cover too vast variances in individual perceptions of taste; intuitively, one may have good reasons to judge something tasty despite it being disliked by the public. A better insight perhaps could be gained by observing the social practice of deference to relevant authorities (such as connoisseurs or art critics) with respect to whether something is tasty. It is certainly not odd to regard Michelin Guide or opinions on Tripadvisor as indicative of whether one may find a tasty meal in a restaurant they wish to visit. But (as disputed in the above section) can we know that Gordon Ramsay serves tasty food merely by Michelin Guide’s testimony? There is a strong intuition that such evaluations do not have any normative force over what other users of the language should consider tasty (see Lasersohn, 2005, f. 8). Even if such intuition is wrong, its existence should be accounted for, and it could not be done by merely stamping our feet and rejecting it.

I think, however, that the existence of definite cases is merely a property of some vague predicates that happen to be primitive and/or unidimensional (that is—having a single scale being the criterion of inclusion into their extension; see Kamp, 1975; Klein, 1980), not a defining feature of the whole class of vague predicates. When we consider whether Musk is rich, we measure his total net worth and nothing else; similarly, when considering whether a cake is sweet, we may appeal to its sugar content (where a spoonful of white sugar is a definite case of “sweet”). Consider “sweet” now as a defining part of another derivative unidimensional predicate:

-

x is mega-sweet if and only if x is sweeter than regular definite cases of “sweet”.

-

or the following derivative two-dimensional predicate:

-

x is swalty if and only if x is sweet and x is salty.

There are, of course, still some definite cases of mega-sweet and swalty—salted caramel being one example of both. However, there are necessarily less definite cases of both mega-sweet and swalty than either “salty” or “sweet”: some borderline cases of “salty” happen to be definitely “sweet” and vice versa, which makes them borderline cases of swalty, while, by definition, there are no swalty things which are not sweet or salty (and similarly one’s evaluation of x being mega-sweet depends on where one puts the threshold for being definitely “sweet” and their qualitative assessment of what counts as a “regular case”).

Once we establish the possibility and basic characteristics of such predicates, one may think of further, more and more complicated and blurry constructions:

-

x is swaltidelicious if and only if x is swalty and x is not mega-sweet or super-salty.

I will call similar and more complicated predicates “super-vague,” their characteristic feature being that the classification of some x as a case of such a predicate itself depends on its classification as more than one primitive and unidimensional vague predicate. In other words, to classify x as a super-vague F, one needs to previously classify x as being in the extension of other vague predicates, such as for the dish to be classified as swalty, it needs to be sweet and salty. Although the above made-up predicates were introduced as derivative and were properly defined in terms of equivalence with being in the extension of other vague predicates, one might think of at least some candidates for primitive super-vague predicates, such as “healthy” or “intelligent.” In such cases, although one cannot provide a list of necessary conditions for being in the predicate’s extension in terms of other predicates, one might presumably think of a variety of sufficient conditions or at least good estimations. One might be classified as healthy after being classified as normal due to a variety of different scales (blood pressure, heart rate, and so on) and as intelligent after being classified as above average on other scales (performance in some tasks, having an extensive vocabulary, etc.). Such super-vague predicates would necessarily be multidimensional, while unidimensional super-vague predicates would necessarily be derivative of some other primitively vague predicates (as mega-sweet, which uses vague predicate “sweet” and an expression “regular” in its definition). Because of this characteristic, all super-vague predicates would have more borderline cases than their primitive, unidimensional source predicates. I claim that “tasty” should be treated as such a super-vague, primitive, and multidimensional predicate with little to no definite cases, or at least cases that cannot be, under certain circumstances, disputed.

What reasons support treating “tasty” as a super-vague predicate, that is—what makes it more similar to “swaltidelicious” or “healthy” than to “tall”? From my perspective, there are at least three good reasons for such a classification. At first, as we saw, super-vague predicates are themselves vague, since being a part of their extension boils down to being a part of an extension of some primitive vague predicates; but unlike them, super-vague predicates need not have any definite cases—it surely might be the case that every relevant object in the basic domain of such predicate (that is, e.g., a dish or a drink in case of “tasty”) is a borderline case. Analysis of faultless disagreement in terms of the predicate’s vagueness is therefore not stopped by the lack of commonly recognized definite examples. It allows us to account for the apparent possibility of faultless disagreement for nearly allFootnote 14 cases in the domain of “tasty.”

Secondly, we should notice that when we give reasons for our evaluation of something as “tasty” (as B did, calling something not tasty because it was too sweet and not spicy and beefy enough), we usually employ our qualitative assessments of some other vague properties of the dish or drink. This points towards that we do seem to base our evaluation of something as “tasty” on our classification of something as “sweet,” “sour,” etc., the perceived balance between those tastes, and so forth. To paraphrase Gareth Evans’ famous remark about the transparency of belief (Evans, 1982, p. 225), when somebody asks me “Do you find this tasty?”, I am not looking into myself or some intimately given property of tastiness but rather evaluate other qualities present in the world, just as a physician does not look for patient’s healthiness but measures their blood pressure and so forth. Although it does not mean that “tasty” is theoretically reducible or definable in terms of some specific combination of primitive vague predicates, it does mean that some bundles of these predicates constitute the tastiness of a dish or a drink in a given context. “Tasty” can be then regarded as primitive and multidimensional, in a way resembling predicates such as “healthy” or “intelligent.”

Multidimensionality of “tasty,” which it shares with other members of the class of primitive super-vague predicates, might be also observed in that it is used as a comparative adjective only if most of the other variables are set at the comparable level. The following conversation does seem to be perfectly natural:

-

A: Which tiramisu is tastier?

-

B: This one. It’s not as offensively sweet as the other one.

This comparison seems intelligible precisely because both dishes are tiramisus—they do have similar characteristics apart from, say, their sweetness. If they are tasty, they are probably tasty because of the same reason (or a similar bundle of reasons), which might be qualitatively compared, while, e.g., a slice of pizza and a roll of sushi might be tasty for different and hence incomparable reasons. We do not witness many contests for the tastiest dish period but rather contests for the best tiramisu, coffee, or pizza, which could be compared on similar scales. It would be borderline nonsensical to ask “Which one is tastier?” if I were to compare a cup of coffee with a slice of pizza, as it would be to ask me “Which one is swaltier?” when comparing salted caramel with caramelized salt but (I presume) not two salted caramels with more and less salt in them.

One might find such characterization of “vagueness” unpersuasive and argue that the existence of non-borderline cases of a predicate is in fact essential: in other words, if all cases of a predicate can be regarded as borderline, we seem to lose any intuitive grip of the very meaning of such predicate and its communicative purpose. Though I stipulated that no case of “tasty” can be thought to be decisive in the sense that it cannot give rise to motivated disagreement in any context, I do not think that this fact significantly threatens a useful analysis of disagreement in terms of vagueness. Saying that no case is decisive with respect to all contexts does not mean that in the specific context of a given disagreement the interlocutors treat all cases as borderline. Presumably, if A and B disagree over the taste of chili and provide reasons for their evaluation in a manner that aims to persuade the other to change their mind, they nevertheless assume their agreement over a range of other cases: that a chili with such-and-such qualities could be regarded as tasty, while a chili lacking them or exhibiting other shortcomings could not. If B asserts that the chili is not tasty and then proceeds to reject that any change in its flavors would make it so (e.g., making it less sweet or spicier), then such disagreement could be plausibly characterized as pointless or merely verbal, and B’s assertion as faulty. Although every case of “tasty” may be in principle justifiably challenged, every such a challenge in a conversation seems to assume a background of firm cases of “tasty” which needs to be adopted by the interlocutor. Hence, even if there are no definite cases of “tasty,” this does not mean that we treat “tasty” as borderless when we disagree.Footnote 15

How does the super-vagueness of “tasty” mix with the NTA-based explanation of the faultlessness intuition? A skeptic might say that the lack of decisive cases threatens the idea that it may be rational to engage in reason-giving. This, however, misses an important point, for the NTA account predicts that such disputes happen not if one believes the case to be decisive, but if the assertion made is judged by the interlocutor to be justified in a way that diverges from the accepted constitutive norm. It may be perfectly rational to challenge another person’s assertion not because we know they are wrong but also because we believe they lack sufficient justification for their claim. By analogy, if another person judges A to be rich, I need not disagree and may very well regard A to be a borderline case of “rich”—but I may still challenge their assertion because I believe it was made based on hearsay or without a good understanding of A’s financial situation. The lack of decisive cases does not make such discussions and challenges irrational.

5 Conclusion

Why do we find ourselves in passionate yet seemingly irresolvable disputes concerning matters of taste? In the present paper, I argued for the surprising conjunction of answers to this question: that we do engage in these disputes because there is something to argue after all—that is our judgments of taste are either absolutely true or false and may be robustly justified—but also that such disagreements, in the majority of cases, cannot be rationally resolved because of our lack of epistemic access to boundaries of vague predicates (as predicted by Williamson’s epistemicism about vagueness). Is it a contradictory result? I do not think so. Our lack of knowledge of some proposition does not entail that all possible justifications of it are made equal. Even if all possible evidence permits two mutually exclusive interpretations of it, it does not mean that every justification would be strong enough; this, I think, is sufficiently visible from the patterns of reasons we employ to convince others that something is tasty or fun and how such disputes usually proceed. Epistemicism about vagueness has both the tools to explain the fact that in these debates we may actually disagree and contradict one another and the fact that, nevertheless, both speakers need not be at fault if we assume that predicates of taste are vague—and therefore is a suitable contender for an explanatory theory of faultless disagreement problem.

In Section. 4, I countered the objection concerning treating predicates of taste as vague, coming from the apparent lack of decisive cases of “tasty.” I argued that predicates of taste should be regarded as super-vague, that is, primitive and multidimensional predicates whose application to an object depends on classifying it as a case of other vague predicates. This proposal allows us also to better grasp the patterns of reason-giving provided in the introduction—since reasons provided for our classification of x as tasty themselves employ vague predicates (such as “sweet,” “sour,” or “balanced”), they may be questioned and become the source of faultless disagreement on the lower level. While in such cases debates remain unresolved, they remain far from irrational.

Notes

I leave aside here the question of moral or aesthetic disagreement; those cases had been given an extensive absolutist, contextual, relativist, and metalinguistic analysis elsewhere.

Of course, they are contextually dependent, since their meaning may differ with respect to a relevant comparison class—John might be rich for an Alabamian, but not necessarily for an inhabitant of San Francisco. This however does not threaten the epistemicist position, as even when a comparison class is fixed, the vagueness of the predicate remains, leaving room for the epistemic position to explain the phenomenon (Williamson 1994, p. 215). Some philosophers tried to analyze vagueness in a contextualist fashion (for a survey, see Åkerman 2012); those positions however usually analyze vague predicates as contextually-dependent but not indexical expressions, as usually contextualists about taste would have it.

One might plausibly wonder whether there is not a disanalogy concerning how these types of disagreement are sometimes resolved: while cases of faultless disagreement involving traditional vague predicates may be resolved by merely stipulating a specific threshold for an application of vague predicates (say, a concrete monetary value of one’s assets for “rich”), the same is intuitively false of predicates of taste. I take it that this difference is brought about by the fact that “tasty,” unlike “rich” is vague over a plentitude of different dimensions interacting with one another and would require a complex stipulation spanning across such dimensions—I elaborate on this property of “tasty” in Section. 4. That is not to say that we cannot approximate this strategy of resolving disagreement—I think it is fairly common to defer to other judges to resolve taste disputes when we accept their authority in matters of taste. I thank the anonymous reviewer for bringing this objection to my attention.

Although I will not discuss in detail the “metalinguistic” approach to such disputes, I assert that in cases of such disagreement claiming that we actually engage in discussion regarding the meaning of the predicate F instead of F’s applicability to x should count as a solution providing a non-straightforward account of contradiction as well, for the contradiction in question does not concern the literal subject of dispute (the dish deemed ‘tasty’ or experience deemed ‘fun’).

For a more detailed treatment of this and other objections to the epistemic interpretation, see Hu 2020.

Goldberg 2015 defends at length a context-sensitive, yet distinctly epistemic account of assertion in line with this observation—according to him, knowledge is the default norm of assertion, while in contexts in which disagreement is especially widespread (e.g., philosophical discourse), this norm might be weakened as the speaker should modestly take the widespread presence of disagreement as evidence that their belief does not constitute knowledge. If we take the widespread disagreement in aesthetic or culinary domains to constitute such contexts, the following considerations may neatly supplement Goldberg’s account.

A different, but still interesting case for conditions of retraction for assertions containing predicates of taste is presented by MacFarlane (2014, pp. 13–14).

Analogously, one could provide a similar norm for assertions containing predicates “fun,” “funny,” or “scary” by changing the admissible scope of properties experienced by the assertor.

As one of the anonymous reviewers of this paper, whom I thank for bringing this to my attention.

In what follows I will directly assume Timothy Williamson’s (1994) analysis of vagueness as ignorance and the meaning of vague predicates as use-dependent. Although competing epistemic accounts (such as Sorensen’s [1988, 2001] or Horwich’s [1998]) could, perhaps, be used instead, I think that the elaborate nature of Williamson’s analysis and its lasting popularity allows me to develop a more precise stance. For these two reasons, of course, one may treat this paper as presenting only a Williamsonian analysis of ‘tasty’, not a general epistemicist analysis of predicates of taste.

Class-based analysis of Bourdieu (1984) comes to mind; but similarly, a convergence in taste judgments with other members of a community may be constitutive of one’s national, regional, or familiar feeling of identity.

One may also present a plausible argument against the undefeatability of the first kind of privilege modeled after Williamson’s (1996, pp. 557–559) anti-luminosity argument, by changing the sorites scenario mentioned in the previous section and replacing the induction premise with the margin-for-error principle for one’s taste. If we accept this argument, then even a qualified assertion of the form “x is tasty to me” is not error-prone.

But consider an example discussed by Elizabeth Anscombe (2000, p. 71), who claims that it is irrational and even unintelligible to sincerely desire to eat a saucer full of mud. Could a saucer of mud be then sincerely considered “tasty” and give rise to a serious and irresolvable disagreement?

One may compare this to the disagreement over simple, unidimensional vague predicates. If A asserts that Bob is rich, while B denies it, they both need to agree that there is at least some range of intuitive applications of “rich” to which Bob might be compared. That is not to say that such cases cannot be challenged in a different context.

References

Åkerman, J. (2012). Contextualist theories of vagueness. Philosophy Compass, 7(7), 470–480.

Anscombe, G. E. M. (2000). Intention. Harvard University Press.

Barker, C. (2009). Clarity and the grammar of skepticism. Mind & Language, 24(3), 253–273.

Barker, C. (2013). Negotiating taste. Inquiry, 56(2–3), 240–257.

Baker, C., & Robson, J. (2017). An absolutist theory of faultless disagreement in aesthetics. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 98(3), 429–448.

Bourdieu, P. (1984). A social critique of the judgement of taste (R. Nice, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bueno, O., & Colyvan, M. (2012). Just what is vagueness? Ratio, 25(1), 19–33.

Collins, J. (2021). A norm of aesthetic assertion and its semantic (in) significance. Inquiry, 64(10), 973–1003.

DeRose, K. (2009). The case for contextualism. Clarendon.

Eriksson, J., & Tiozzo, M. (2016). Matters of ambiguity: Faultless disagreement, relativism and realism. Philosophical Studies, 173, 1517–1536.

Evans, G. (1982). The varieties of reference. Clarendon Press.

Goldberg, S. (2015). Assertion: On the philosophical significance of assertoric speech. Oxford University Press.

Hills, A. (2013). Faultless moral disagreement. Ratio, 26(4), 410–427.

Hîncu, M., & Zeman, D. (2021). On Wyatt’s absolutist account of faultless disagreement in matters of personal taste. Theoria, 87(5), 1322–1341.

Horwich, P. (1998). Meaning. Oxford University Press.

Hu, X. (2020). The epistemic account of faultless disagreement. Synthese, 197(6), 2613–2630.

Huvenes, T. T. (2014). Disagreement without error. Erkenntnis, 79(1, Supplement), 143–154.

Iacona, A. (2008). Faultless or disagreement. In M. García-Carpintero & M. Kölbel (Eds.), Relative truth (pp. 287–295). Oxford University Press.

Kamp, H. (1975). Two theories about adjectives. In E. L. Keenan (Ed.), Formal Semantics of Natural Language (pp. 123–155). Cambridge University Press.

Karczewska, N. (2016). Disagreement about taste as disagreement about the discourse: Problems and limitations. Studies in Logic, Grammar and Rhetoric, 46(1), 103–117.

Klein, E. (1980). A semantics for positive and comparative adjectives. Linguistics and Philosophy, 4, 1–45.

Kölbel, M. (2004). III—Faultless disagreement. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 104(1), 53–73.

Lasersohn, P. (2005). Context dependence, disagreement, and predicates of personal taste. Linguistics and Philosophy, 28(6), 643–686.

Lasersohn, P. (2008). Quantification and perspective in relativist semantics. Philosophical Perspectives, 22, 305–337.

Lasersohn, P. (2009). Relative truth, speaker commitment, and control of implicit arguments. Synthese, 166(2), 359–374.

MacFarlane, J. (2014). Assessment sensitivity: Relative truth and its applications. Oxford University Press.

Moltmann, F. (2010). Relative truth and the first person. Philosophical Studies, 150(2), 187–220.

Muelder Eaton, M. (2001). Merit, aesthetic and ethical. Oxford University Press.

Odrowąż-Sypniewska, J. (2021). Faultless and genuine disagreement over vague predicates. Theoria, 87(1), 152–166.

Pearson, H. (2013). A judge-free semantics for predicates of personal taste. Journal of Semantics, 30(1), 103–154.

Schafer, K. (2011). Faultless disagreement and aesthetic realism. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 82(2), 265–286.

Schaffer, J. (2011). Perspective in taste predicates and epistemic modals. In: Andy Egan & Brian Weatherson (eds.), Epistemic modality (pp. 179–226). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schellekens, E. (2006). Towards a reasonable objectivism for aesthetic judgements. The British Journal of Aesthetics, 46, 163–177.

Silk, A. (2016). Discourse contextualism. A framework for contextualist semantics and pragmatics. Oxford University Press.

Sorensen, R. A. (1988). Blindspots. Oxford University Press.

Sorensen, R. A. (2001). Vagueness and contradiction. Clarendon Press.

Stojanovic, I. (2007). Talking about taste: Disagreement, implicit arguments, and relative truth. Linguistics and Philosophy, 30(6), 691–706.

Stojanovic, I. (2017). Context and disagreement. Cadernos De Estudos Linguísticos, 59(1), 9–22.

Williamson, T. (1994). Vagueness. Routledge.

Williamson, T. (1996). Cognitive homelessness. The Journal of Philosophy, 93(11), 554–573.

Williamson, T. (2000). Knowledge and its limits. Oxford University Press.

Wright, C. (2001). On being in a quandary. Relativism Vagueness Logical Revisionism. Mind, 110(437), 45–98.

Wyatt, J. (2018). Absolutely tasty: An examination of predicates of personal taste and faultless disagreement. Inquiry, 61(3), 252–280.

Wyatt, J., Zakkou, J., & Zeman, D. (Eds.). (2022). Perspectives on taste: Aesthetics, language, metaphysics, and experimental philosophy. London: Routledge.

Zakkou, J. (2019b). Denial and retraction: A challenge for theories of taste predicates. Synthese, 196(4), 1555–1573.

Zakkou, J. (2019a). Faultless disagreement: A defense of contextualism in the realm of personal taste. Frankfurt am Main: Vittorio Klostermann.

Zeman, D. (2019). Faultless disagreement. In: Martin Kusch (Ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Philosophy of Relativism (pp. 486–495). London: Routledge.

Zouhar, M. (2018). Conversations about taste, contextualism, and non-doxastic attitudes. Philosophical Papers, 47(3), 429–460.

Zouhar, M. (2020). Absolutism about taste and faultless disagreement. Acta Analytica, 35(2), 273–288.

Funding

The work on this project was supported by the grant from the National Science Centre in Cracow (NCN), Project Number 2021/41/N/HS1/01586.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tarnowski, M. Knowing What One Likes: Epistemicist Solution to Faultless Disagreement. Acta Anal (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12136-024-00593-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12136-024-00593-4