Abstract

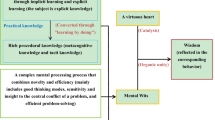

Reaching understanding is one of our central epistemic goals, dictated by our important motivational epistemic virtue, namely inquisitiveness about the way things hang together. Understanding of humanly important causal dependencies is also the basic factual-theoretic ingredient of wisdom on the anthropocentric view proposed in the article. It appears at two levels. At the first level of immediate, spontaneous wisdom, it is paired with practical knowledge and motivation (phronesis), and encompasses understanding of oneself (a distinct level of self-knowledge having to do with one’s dispositions capacities, vulnerabilities, and ways of reacting), of other people, of possibilities of meaningful life, and of relevant courses of events. It is partly resistant to skeptical scenarios, but not completely. On the second and reflective level, understanding helps fuller holistic integration of one’s first order practical and factual-theoretic knowledge and motivation, thus minimizing potential and actual conflicts between all these components. It also participates in the reflective control whose exercise is needed for full reflective wisdom, the crucial epistemic-practical virtue or human excellence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

I wish to thank the organizers and participants of the 2011 Bled Conference on Knowledge, Wisdom and Understanding; special thanks go to V. Tiberius for making me interested in the topic, K. Lehrer and E. Sosa for their inspiring work and friendly discussion, to my friend F. Klampfer for excellent criticisms, my students Anton Ožbej for pressing me on the genesis of wisdom and Nina Iskra for long enthusiastic rounds of conversations about wisdom. The conference participants J. Greco, J. Morton, E. Fricker, and C. Kelp deserve special thanks for inspiring discussion and penetrating criticisms.

Consider the following quotation from Xin Zhong Yao commenting on classical Chinese tradition:

In Confucian terminology, “knowing humans (zhiren)” is to know humans as individuals and as a species, including an understanding of the human person, activity, community, and history, and a comprehension of moral rules, conventions, and virtues. For them, understanding and comprehension are intended to guide behavior and provide patterns to society. In this sense, “knowing humans” is not merely an analytical process, but also involves both factual and evaluative, particular, and universal elements; it integrates all knowing and practical activities into one single effort of fully understanding humans. (2006: 350).

The Greco-Roman discourse of wisdom points in the same direction, stressing the understanding of circumstances, of people, and of oneself. Here is a comment by L-A. Dorion, bringing some fine quotes:

The Socratic intellectualist tradition probably exaggerated the importance of knowledge. Contrary to the opinion that is widespread among most human beings, knowledge is something that possesses a strength (ischuron, Prot. 352b4), as well as a power of guiding (hêgemonikon, 352b4) and commanding (archikon, 352b4), so that it is superfluous to subjoin to it the domination exercised by enkrateia. Cf. Prot. 358c: ‘To give in to oneself is nothing other than ignorance, and to control’ (Dorion, 2007: 126).

Let me explain. The expression “x-centric,” for the given x, embraces several components. One is the claim that x is the prime carrier of wisdom, for example, for the theo-centric view, all wisdom comes from god (either from Marduk, in the case of Babylonian wisdom literature, or from the Lord, “and is with him for ever”, as in the Bible (Sirach, 1.1.), or from some other divinity). The other is the claim that human wisdom, if there is such, has to be concerned with x. For example, for the biblical theocentric view, the fullness of wisdom is to fear the Lord (Ibid.,1,16), and for Marcus Aurelius’s more cosmo-centric one to get attuned to the cosmic “ruling principle.” The third is that the x-wisdom is the prototype of and a paradigm for human wisdom (for x = human, the second and third claims are trivial).

If a given x-focused view does not embrace all three claims, I propose that we treat it as weakly x-centric, and if it embraces all three, as fully x-centric. For instance, Plato does not explicitly ascribe wisdom to Being, but does, in the famous analogy with sun and its light in the Republic, describe the idea of the good as providing knowledge-insight to the inquiring humans. Since the prime object of the human insight are ideas including the idea of the good, since the education is structured by assimilation of the human soul to the order of the ideal cosmos (first, by study of astronomy and mathematics, then by dialectic), we can count Plato’s conception as ontocentric (or cosmocentric if we take the world of ideas as a cosmos).

The next important contrast is between the merely practical and the more or fully reflective approaches. The merely practical approach is exemplified by proverbs of all kinds and sources. An initial stage of the reflective approach is to be found in more-or-less argumentative non-philosophical wisdom literature. An example is offered by the Middle Eastern discussion of the plight of the rightful sufferer in ancient works like Ludlul-bel-nemeqi, Babylonian theodicy and The Book of Job. The fully reflective approach is typically philosophical, involving definition (or its weaker cognates), systematization, and attempts at in-depth explanation.

John Kekes sees wisdom as involving interpretive knowledge, i.e., knowledge of significance as opposed to knowledge of facts. It encompasses three kinds: knowledge of general, ahistorical categories, knowledge of which conventions are necessary and which arbitrary, and knowing how to connect basic beliefs and conventions of our traditions with our character and circumstances (Kekes 1988:148).

Thanks to Friderik Klampfer.

Katharine J. Dell writes:

The thought-world of Proverbs is that of “the act–consequence relationship”(…), that is, the principle that good and bad deeds have consequence that can be known through the study of patterns of human behavior. This principle and various other insights into human characteristics are summed in pithy proverbial sayings, the fruit of the experiences of many generations (2001:418).

The ancient views of taking care of the self have nowadays been revived by P. Hadot, M. Foucault, and by his critics like B. Inwood (see References).

For instance David Dunning in his book on “self-insight” talks about “self-perceptions of competence” (2005:5) and of “the notions people have about their skills and knowledge” (2005: 6).

Kant and Confucius would disagree; the former stresses the awareness of duties and seems to be very much in favor of top-down control. For Confucius, as summarized in the New World Encyclopaedia (http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Wisdom), reflection is the noblest way for learning wisdom, whereas imitation is the easiest , and experience the most bitter.

Thanks go to John Greco for inspiring discussions and for sending me the draft manuscript.

This is why the proverbial wisdom is so often couched in explicit or implicit conditionals, prefaced or accompanied by the point of the conditional, like the following:

He who does a kindness is remembered afterward; when he falls, he finds a support (Sirach).

You should not vouch for someone: that man will have a hold on you (The Instructions of Shuruppag, 19-20) .

You should not speak improperly; later it will lay a trap for you. (Ibid., 42-43.)

References

Charron, P.-A. D. (1827). De la Sagesse, trois livres. Paris: Rapilly.

Dell, K. J. (2001). Wisdom Literature. In L. G. Perdue (Ed.), The Blackwell Companion to the Hebrew Bible. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

Dorion, L.-A. (2007). Plato and ENKRATEIA. In C. Bobonich & P. Destrée (Eds.), Akrasia in Greek Philosophy, From Socrates to Plotinus. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill.

Haidt, J. (2005). The Happiness Hypothesis: Finding Modern Truth in Ancient Wisdom. Cambridge: Basic Books.

Kane, R. (2010). Ethics and the Quest for Wisdom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kekes, J. (1988). The examined life. Bucknell University Press: Lewisburg; London: London Associated University Presses.

Kirk, G. S., Raven, V. E., & Schofield, M. (Eds.). (1983). The Presocratic Philosophers: A Critical History with a Selection of Texts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kornblith, H. (2010). What Reflective Endorsement Cannot Do. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, LXXX(1), 1–19.

Kvanvig, J. (2003). The Value of Knowledge and the Pursuit of Understanding. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lackey, J. (2010). Learning from Words: Testimony as a Source of Knowledge. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lehrer, K. (1997). Self-Trust. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Nozick, R. (1989). The Examined Life. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Perry, J. (1998). The Self. In The Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Supplement (pp. 524–526). New York: Simon & Schuster Macmillan.

Sosa, E. (2001). Goldman’s Reliabilism and Virtue Epistemology. Philosophical Topics, 29(1/2), 383–400.

Sosa, E. (2007). A Virtue Epistemology. Apt Belief and Reflective Knowledge, Volume I, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stalnaker, R. C. (2008). Our Knowledge of the Internal World. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Tiberius, V. (2008). The Reflective Life, Living Wisely within our Limits. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Zagzebski, L. T. (1996). Virtues of the Mind: An Inquiry into the Nature of Virtue and the Ethical Foundations of Knowledge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Miščević, N. Wisdom, Understanding and Knowledge: A Virtue-Theoretic Proposal. Acta Anal 27, 127–144 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12136-012-0156-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12136-012-0156-2