Abstract

Recent research shows that better educated and structurally integrated immigrants do not articulate more positive attitudes toward the ethnic majority than immigrants who have lower levels of educational attainment, described as evidence of an “integration paradox.” While these findings have important implications for theories of immigrant integration, they stand in contrast with theories of intergroup relations, e.g., intergroup contact theory. Importantly, these findings also challenge the strong theoretical expectation that higher levels of education generate more positive intergroup attitudes, that is, the universality of the educational effect. Using four waves from ‘New Immigrants Survey Netherlands’ (NIS2NL) survey, I investigate attitudinal differences toward both the ethnic majority and other ethnic minorities in the Netherlands for four recent immigrant groups by focusing on the highest level of education from their country of origin. First, I analyze whether the relationship between education and outgroup attitudes differs toward the ethnic majority and toward ethnic minorities. Second, I look at how attitudes toward outgroups change over time. Findings indicate that immigrants with higher levels of educational attainment hold more positive attitudes toward other ethnic minority groups, and these attitudes are stable over time. Attitudes toward the ethnic majority, however, are initially very positive but become less so over time, regardless of level of education. The findings shed new light on the universality of the educational effect on interethnic attitudes by showing that higher levels of education among immigrants have a potential “liberalizing” effect only toward minority groups, but not toward the ethnic majority.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recent research shows that better educated and structurally integrated immigrants do not articulate more positive attitudes toward the native-born and ethnic majority than immigrants who have lower levels of educational attainment (de Vroome et al., 2014; Teije et al., 2013; Tolsma et al., 2012; Verkuyten, 2016). These seemingly counterintuitive findings have been described as evidence of an “integration paradox” (Schaeffer & Kas, 2023) and are attributed to higher levels of perceived discrimination among better-educated immigrants (van Doorn et al., 2013), which negatively affects how they feel about the members of the host society, as well as their sense of belonging (Geurts et al., 2020).

While these empirical findings have important implications for theories of immigrant integration, they stand in stark contrast with theories of intergroup relations. For instance, they contradict intergroup contact theory (Allport, 1954); insofar as better integrated, highly educated immigrants have greater contact with the native/ethnic majority (Martinovic et al., 2009), they should hold more positive attitudes toward them. Importantly, these findings also challenge the strong theoretical expectation that higher levels of education generate more positive intergroup attitudes (Hainmueller & Hiscox, 2007; Hello et al., 2006; Hjerm, 2001; Hooghe et al., 2013). Indeed, the inverse relationship between education and prejudice is arguably the most consistent empirical finding in studies of inter-ethnic relations (Vogt, 1997) and anti-immigrant sentiment (Ceobanu & Escandell, 2010). This strong correlation is most noticeable when discerning between individuals with a tertiary degree and those without one (Hainmueller & Hiscox, 2007).

How can we understand these divergent empirical results? Previous research on prejudice has primarily focused on the relationship between levels of educational attainment among native-born, ethnic, and/or racial majorities and their attitudes toward ethnic minorities and immigrants. Although studies on the integration paradox examine the association between educational attainment of ethnic minorities and their attitudes toward the native-born and ethnic majority, this literature has neglected the relationship between immigrants’ level of education and their attitudes toward other ethnic minority groups, and how they develop over time. Thus, it remains unclear the extent to which this educational effect is “universal” i.e., whether it is also present among immigrants and ethnic minorities.

The presence of an integration paradox for highly educated immigrants is worthy of attention, since they would be the most likely to pass exams measuring language skills and knowledge of the host society. This paradox has not been investigated systematically in other countries (Verkuyten, 2016), thus, the Netherlands provides an opportunity to further investigate this by building on previous literature, and contributing by analyzing to what extent immigrants’ level of education from their country of origin shapes their attitudes toward the native Dutch and other ethnic minority groups in a longitudinal perspective.

To do this, I rely on data from four waves of the ‘New Immigrants Survey Netherlands’ (NIS2NL), collected in the years 2013–2018 for recent immigrants to the Netherlands from Spain, Poland, Bulgaria, and Turkey. The Netherlands, like most Western democracies, has seen a considerable change in its ethnic composition in past decades, with immigrants making up a considerable share of EU residents (Van Der Zwan et al., 2017). As of 2019, immigrants in the Netherlands, including second generation immigrants with at least one parent born abroad, made up 23.6% of the population: 12.5% first-generation and 11.1% second-generation (Statistics Netherlands, 2019). This makes inter-minority attitudes something important to study, which is often neglected in migration and integration research.

In this study, I investigate the role of education from the country of origin on recent immigrants’ attitudes toward both the ethnic majority and other ethnic minorities in the Netherlands. First, I investigate whether the relationship between education and outgroup attitudes differs depending on whether the outgroup is the native majority or other ethnic minorities. Second, I examine how attitudes toward outgroups change over time depending on different levels of educational attainment. By doing this, I can speak to what extent this relationship holds among immigrants, and if it varies depending on the ethnicity of the outgroup. By examining if education matters for immigrants’ attitudes toward different ethnic outgroups in the host society, I provide greater insight into the universality of the educational effect.

Theory and Hypotheses

Integration Paradox

Research on the integration paradox postulates that there is a negative relationship between structural integration and level of education, and positive attitudes toward natives and the host society. One possible explanation for the integration paradox is the “theory of exposure,” (van Doorn et al., 2013) which suggests that highly educated immigrants experience more discrimination since they consume more media and have more contact with natives in the labor market and associations, therefore being more exposed to discrimination. A second argument is that highly educated immigrants hold more sophisticated cognitive abilities (Bobo & Licari, 1989; Wodtke, 2012) and are therefore more aware of discrimination in the destination country and their lower status as immigrants. Moreover, highly educated immigrants develop higher expectations which are not always met (Verkuyten, 2016; see also Thijssen et al., 2021), thus leading to a feeling of relative deprivation when comparing themselves to the group that they most often have contact with, i.e. natives with similar levels of education.

Studies in the Netherlands have shown that although highly educated minorities have more opportunities for contact with natives, they do not necessarily have more positive contact and meet less discrimination (Tolsma et al., 2012). In other words, minorities with higher levels of education are more likely to experience interpersonal contact with members of the ethnic majority, but these interactions lead minorities to view the majority less positively. Moreover, the relationship between minorities’ perceived discrimination/less societal acceptance and their attitudes toward the native population and the host society is strongest among those with higher levels of education (de Vroome et al., 2014; Teije et al., 2013). This also seems to be the case in Germany (Steinmann, 2019; see also Tuppat & Gerhards, 2021), implying that this phenomenon is not endemic to the Netherlands. In addition, research has shown that a longer duration in the destination country is associated with more discrimination (McGinnity & Gijsberts, 2018), which suggests that the attitudes of immigrants with the most education should also worsen over time.

The integration paradox has also been found to exist among smaller immigrant groups in the Netherlands (Geurts et al., 2020; van Doorn et al., 2013), suggesting similar integration processes (or lack thereof) among various immigrant groups. It is therefore not specific to the four largest immigrant groups, i.e., Turks, Moroccans, Surinamese, and Antilleans. Considering this, higher levels of education among immigrants should not result in more positive attitudes toward the ethnic majority, although this may differ toward other ethnic minorities. This finding, however, has failed to be replicated among adolescents in the Netherlands, indicating that the integration paradox is limited to migrants who do not grow up in the host society, or that young immigrants’ attitudes toward the ethnic majority drastically change after high school (van Maaren & van de Rijt 2020).

The absence of the relationship consistently found in studies of natives’ attitudes toward immigrants and ethnic/racial minorities challenges the notion that more education always means more positive attitudes toward outgroups. This is key since more education is often regarded as a way to integrate immigrants and improve their commitment and identification with the host society. And yet, there is evidence that higher levels of education among the immigrant population do not necessarily translate into more positive attitudes toward the native ethnic majority, mainly due to perceived discrimination, which likely increases over time (McGinnity & Gijsberts, 2018). Therefore, I hypothesize that due to the integration paradox:

-

H1a: Higher levels of educational attainment are not associated with more positive attitudes toward the ethnic majority in a destination country.

-

H1b: Attitudes toward the ethnic majority become less positive over time.

Education and outgroup attitudes

Research that has focused on the effect of education and prejudice (e.g., Creighton et al., 2023; Hello et al., 2002, 2006; Meeusen et al., 2013; Mulders & van Tubergen, 2022; Velásquez & Eger, 2022) has largely looked at the inverse relationship between education and prejudice among ethnic and racial majorities and native-born. Meanwhile, empirical studies on the effect of education on immigrants’ attitudes toward natives and toward other immigrants and minorities is scarce (Roth & Kim, 2013), leaving the question open as to whether this robust statistical relationship also exists among immigrants.

Yet, previous studies that have investigated inter-minority attitudes have not focused on education. In the United States, Philip et al. (2010) looked at the differences in attitudes toward African-Americans among Indian immigrants and Indian-Americans, and showed that Indian immigrants hold more negative attitudes toward African-Americans, due to lack of contact, as well as beliefs about social hierarchies, inter alia. Despite this, ethnic minority groups at times may share their minority position in society and the feeling of being “in the same boat,” which could trigger a common disadvantaged minority ingroup identity that results in more positive attitudes toward other minorities (Craig & Richeson, 2012).

In a study of 23 European countries, Van Der Zwan et al. (2017) found that perceived migrant threat among immigrants was stronger among those who had lived longer in the destination country, and the more education a migrant had, the weaker their threat perceptions were toward other migrants. In Belgium, Meeusen et al. (2019) showed that Belgians of Turkish and Moroccan descent were not exempt from having negative attitudes toward immigrants in general, and these were more negative when it specifically concerned Eastern European immigrants, with a slight majority believing Eastern Europeans take their jobs and ruin the reputation of other immigrants. In a study among secondary school students in the Netherlands, Verkuyten et al. (1996) found that students with Turkish, Moroccan and Surinamese background considered the Dutch the most preferred outgroup, and that Turks and Moroccans had more favorable attitudes toward each other than to the Surinamese. Similarly, Hindriks et al. (2014) found that more social distance was reported by Turks and Moroccans toward Surinamese/Antilleans than toward each other.

These studies suggest two important things: First, similar groups are evaluated more positively (McPherson et al., 2001); Second, the ethnic majority population (at least in the Netherlands) is the most positively viewed outgroup by ethnic minorities, after their own group. Yet, these studies have not particularly focused on education and its effects on inter-minority attitudes, and on attitudes toward the ethnic majority. Research has also not investigated whether these attitudes change over time, despite existing evidence that the effects of education may vary across groups. For instance, Hindriks et al., (2014) found that higher levels of education are associated with less social distance toward other minority groups but not toward the native Dutch. In fact, this association is reversed toward the native Dutch, albeit the effect size is rather small and weak. In contrast, Meeusen et al. (2019) found that Belgian Turks and Moroccans show no significant differences in their anti-immigrant attitudes by level of education. The authors speculate that this is likely due to the majority of respondents in the sample being in low socio-economic positions.

To summarize, the few studies on inter-minority attitudes have not focused on the effect of education on these attitudes, while evidence suggests it may operate differently toward other minority groups than toward the ethnic majority. Still, education is consistently shown to be a strong predictor of pro-immigrant attitudes (Ceobanu & Escandell, 2010; Hainmueller & Hiscox, 2007; Hello et al., 2002). Therefore, due to strong theoretical expectations on the educational effect on attitudes toward immigrants, I hypothesize:

-

H2a: Higher levels of educational attainment are associated with more positive attitudes toward other ethnic minority groups in a destination country.

In addition, since there are no strong theoretical expectations for inter-minority attitudes to change over time by level of education, as there is toward the ethnic majority, I hypothesize:

-

H2b: Attitudes toward other ethnic minority groups are stable over time.

Data

Data come from the ‘New Immigrants Survey Netherlands’ (NIS2NL) for the years 2013–2018. This is a survey designed to analyze early integration processes of recently arrived immigrants to the Netherlands from Spain, Poland, Bulgaria, and Turkey (Lubbers et al., 2018). Information for the first wave was collected in November 2013 and March 2014 for migrants who had registered in a Dutch municipality less than eighteen months before September 2013. The mean response rate was 32.3% leading to a total of 4,808 respondents in the first wave. In the second, third and fourth waves, respondents were approached in March and May 2015; September 2016; and January 2018, respectively.

In the original dataset, 4,808 individuals were interviewed. However due to missing values mainly on the dependent variables, the sample includes a total 4,323 individuals: 1,254 (29%) Spaniards; 1,622 (37.5%) Poles; 687 (15.9%) Bulgarians, and 760 (17.6%) Turks. The number of respondents is 4,323 in wave 1; 2,069 in wave 2; 1,230 in wave 3, and 901 in the last wave. In order to test hypotheses H1a and H2a, I only use the first wave since the highest level of education is from the immigrants’ country of origin and therefore time-invariant in the analyses. The reason for not using highest level of education attained in the Netherlands is due to data limitations that do not capture adequate educational attainment in the destination country as well as a high attrition rate. The dropout between waves can be selective to a certain degree, due to the nature of immigrants’ mobility and wishes to return to their country of origin or migrate to other countries. While testing hypotheses H2a and H2b, I complement the analyses with a balanced sample (Table A7 in Appendix) with respondents who participated in all waves, which can better represent the migrant population that eventually stays in the country.

Dependent Variables

The dependent variables are based on “feeling thermometer” questions asking respondents how they feel toward different ethnic groups: native Dutch, Spaniards, Poles, Bulgarians, and Turks. Feeling thermometer questions are a reliable way to measure attitudes (Alwin, 1997) and are commonly used in ethnic studies, including research in the Netherlands (Coenders et al., 2008; de Vroome et al., 2014; Geurts et al., 2020; Velthuis et al., 2021; Weber, 2022). Respondents are asked to imagine a thermometer and can specify a temperature between 0 to 100 with 10-degree intervals representing how they feel about a given group. In the original dataset, the responses are coded on a 0–10 scale with 0 degrees representing very negative attitudes, and 100 degrees (coded as 10) meaning they feel very positively toward the group. As robustness checks, I also create two alternative dependent variables which are presented in Table A6 in the Appendix. For the first alternative dependent variable, I subtract ingroup attitudes from attitudes toward the ethnic majority. Similarly for the second one, I subtract ingroup attitudes from the average attitudes toward other ethnic minorities. By doing so, I am able to “isolate changes in the relative views of the targeted group and shifts in a willingness to apply stereotypes generally are thus deliberately removed” (Hopkins & Washington, 2020: 8).

Main Independent Variable

The main independent variable is highest level of educational attainment in the country of origin. Many of the respondents in the sample have not pursued higher education in the Netherlands and graduated with a degree (around 92%), and a vast majority of those who did pursue higher education already had a university degree. To test my hypotheses, I use a three-category version of education: 0 “Less than Secondary” 1 “Secondary” 2 “Tertiary.” This three-category variable was constructed from a 9-category variable ranging from “less than primary” to “Doctoral” education. This was done due to very low numbers in some categories and even zero for others (e.g., no Bulgarians with a master’s degree, or Turks with a doctoral degree).

Controls

In order to isolate education’s effect from other SES indicators, I use immigrants’ employment status (main activity) in the Netherlands: Unemployed; Employed; Non-employed; In Education. The first category captures individuals who are currently unemployed. The second category consists of individuals who are currently working, including those who are temporarily on parental leave. The third category ‘non-employed’ consists of individuals who are long term sick or disabled, retired, or looking after the home/children as their main activity and are not searching for a job. The fourth category refers to individuals who are currently enrolled in any type of education. Due to a substantial number of missing values for income (N≈700), this control is not added in the main analyses, but in additional analyses in the Appendix (see models in Tables A1-A7).

As basic demographic controls, I include the continuous measure of age, and a binary measure of sex. Other relevant controls included are perceived group discrimination and contact with native Dutch. Perceived group discrimination is captured by answers to the question: “Some say that people from [country of origin] are being discriminated against in the Netherlands. How often do you think [country of origin] people are discriminated against in the Netherlands?” I then constructed a 4-category variable: Never/Almost Never; Sometimes; Often/Very Often; Do not know. Contact with native DutchFootnote 1 consists of 6-categories: Never; Less often; Several times a year; A few times a month; Several times a week; Every day, answering to the question “How often do you spend time with Dutch people in your free time?”.

Estimation

I restrict the sample to exclude ingroup attitudes in the models. In this manner, the number of respondents becomes 3,069 for attitudes toward Spaniards; Poles 2,071; Bulgarians 3,636; and Turks 3,563. In additional analyses using alternative dependent variables (Table A6 in the Appendix), the number of respondents is 4,323 for both attitudes toward the ethnic majority, and toward ethnic minorities.

Methods

To test the hypotheses, I analyze data with ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions for hypotheses H1a and H2a due to the time-invariant nature of the key independent variable. In order to test H1b and H2b I use mixed, multilevel repeated measurement models. These are hierarchical models, with observations (time) nested in individuals. This approach estimates fixed-effects and two random-effects, corresponding to the between-individual (intercepts) and within-individual (residuals) variances. The generic model using a single equation looks like this:

Where \({y}_{ij}\) is the dependent variable measured for i th level-1 unit (observations) nested within the j th level-2 unit (individuals). The fixed-part of the model consists of the intercept \({\beta }_{0}\) and covariates \({\beta }_{1}{x}_{1}\)+… \({\beta }_{n}{x}_{n}\). The random-part consists of \({u}_{j}\), the residual variance of the level-2 units (individuals) and \({e}_{ij}\), the residual variance of the level-1 units (observations).

This can also be written as a set of hierarchical equations:

With \({\gamma }_{00}\) referring to the overall intercept, \({\gamma }_{01}\) the overall regression coefficient, \({w}_{j}\) a level-2 predictor (individual), \({u}_{0j}\) the random error component for the deviation of individuals’ intercepts from the overall intercept, \({\gamma }_{10}\) the overall regression coefficient between the dependent variable and level-1 predictor, \({\gamma }_{11}\) the regression coefficient for covariate \({w}_{j}\) and \({u}_{1j}\) the error component for the slope. A random slope for time is also included in the analyses for purposes of cross-level interactions (Heisig & Schaeffer, 2019).

Results

Descriptive statistics

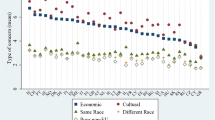

The descriptive statistics for this study are presented in Table 1. The average response to the first dependent variable capturing attitudes toward the ethnic majority is 7.24 over the four waves. The average attitudes toward ethnic minorities (excluding ingroup attitudes) are Spaniards (5.44), Poles (5.29), Bulgarians (4.58), and Turks (4.46). About 54% of the sample has tertiary education, 30% secondary education, and 16% less than secondary education. Figure 1 below shows a fine-grained version of educational attainment in the sample by immigrant group. The majority (62%) are employed, 15% are unemployed, 8% are “non-employed,” and 15% are enrolled in some type of education. There are more women (55%) than men (45%), and the average age of respondents is 32 years old. Most respondents in the sample come from Poland (37%), followed by Spaniards (29%), Turks (18%), and Bulgarians (16%).

Figure 1 shows the distribution of educational levels by immigrant group. The vast majority of Spaniards in the sample have tertiary education (81.2%). 45.8% of Poles have tertiary education; 33.8% of Bulgarians; and 47% Turks. Respondents with tertiary education form the largest educational category for each immigrant group, except for Bulgarians who mostly have secondary education (58.2%) as their highest level of completed education in their country of origin.

Figure 2 illustrates mean attitudes by country of origin, including attitudes toward their own ethnic group, for comparison purposes. It is noteworthy that all immigrant groups regard the native Dutch more positively than other ethnic groups, even their own, except for respondents from Spain, who regard their own group the most favorably. The next most favored group is the ingroup, followed by Spaniards, Poles, Bulgarians, and Turks.

Empirical Analyses

In Table 2, I report results from the test of hypotheses H1a in Models 1–2 and H2a in Models 3–10. I begin with model 1, including only the trichotomous education variable. Results show support for H1a in that having higher levels of education from the country of origin are not associated with more positive attitudes toward the ethnic majority. These analyses are also corroborated in Table A1 in the Appendix, where I analyze separately each immigrant group’s attitudes toward the ethnic majority. In model 2, controls are added showing that being employed, non-employed or in education does not seem to have an effect on attitudes toward the ethnic majority when compared to those who are unemployed. In addition, respondents who perceive more group discrimination hold more negative attitudes toward the ethnic majority. Respondents who have more contact with the native Dutch, however, hold more positive attitudes toward them.

In the following models (3–10), attitudes toward the different ethnic minorities are shown excluding ingroup attitudes. These models show a consistent relationship between higher levels of education and more positive attitudes toward other ethnic minorities, thus supporting hypothesis H2a. In addition, separate analyses were conducted for each immigrant group in Tables A1-A5 in the Appendix. These analyses show a consistent relationship between higher levels of education and more positive attitudes toward other ethnic minorities among all immigrant groups, except for Poles’ and Bulgarians’ attitudes toward Turks, where no effect of education is found (Tables A3-A4).

Models 3–10 in Table 2 also show respondents who are currently in some type of education to hold more positive attitudes toward the other immigrant groups, except for Turks, when compared to those who are unemployed. Similarly, as in previous models, those who perceive more discrimination toward their own ethnic group hold less positive attitudes toward other ethnic minorities, while those who have more contact with the native Dutch, hold, on average, more positive attitudes.

In Table 3, results for hypotheses H1b and H2b are presented. In model 11, time as a continuous variable is added. This shows a negative linear trend over time for attitudes toward the ethnic majority, providing support for H1b. In model 12, I interact level of education with time and this result is illustrated in Fig. 3. Additional analyses using an alternative dependent variable, and a balanced panel (Tables A6-A7 in the Appendix) confirm these results.

In models 13–20, similar analyses were conducted showing attitudes toward other ethnic minorities are, for the most part, stable over time. Attitudes toward Bulgarians seem to become slightly more positive over time, whereas attitudes toward Turks become slightly more less positive over time. These time trends, however, are not as strong and pronounced as those captured toward the ethnic majority. Additional analyses were conducted using an alternative dependent variable and in a balanced sample in Tables A6-A7 in the Appendix, showing stability in attitudes toward other ethnic minorities, thus showing support for H2b.

Conclusion

Previous research has consistently shown a relationship between higher levels of education and lower levels of prejudice. However, studies have mostly relied on analyzing this relationship among ethnic and racial majorities and native-born, leaving the question open as to whether the educational effect is indeed present among immigrants toward the ethnic majority. In addition, research that has focused on inter-minority attitudes has also failed to investigate whether the educational effect is present among immigrants and ethnic minorities. In this study, I have sought to contribute to this gap in the literature by analyzing attitudes toward different outgroups among immigrants in the Netherlands, consisting of attitudes toward the ethnic majority (native Dutch), and toward other ethnic minorities in a longitudinal perspective.

Using four waves from the ‘New Immigrants Survey Netherlands’ (NIS2NL), my main objectives were: (1) to investigate to what extent educational attainment was associated with more positive inter-ethnic attitudes among four recent immigrant ingroups in the Netherlands, as it has repeatedly been shown to be the case among the native-born and ethnic majority (e.g., Hainmueller & Hiscox, 2007); and (2) to examine if these attitudes had different trajectories over time. Hypotheses H1a and H1b tested the effect of education from the country of origin on attitudes toward the ethnic majority. Consistent with the integration paradox, I found support for both hypotheses, inasmuch as higher levels of educational attainment are not associated with more positive attitudes toward the ethnic majority, and that these attitudes become less positive over time. Hypotheses H2a and H2b, were derived from strong theoretical expectations of the universality of the educational effect on outgroup attitudes. I hypothesized that higher levels of educational attainment were associated with more positive attitudes toward other ethnic minorities, and that these attitudes were stable over time. The results also provided support for these hypotheses.

I acknowledgements several limitations of the present study. First, this research cannot rule out potential self-selection mechanisms into higher education (e.g. Lancee & Sarrasin, 2015), and the effect of field of study on prejudice (Feldman & Newcomb, 1969; Guimond et al., 2003; Guimond & Palmer, 1996). Due to data limitations, I am not able to address these issues, which become more complex when taking into account the different educational systems from the immigrants’ country of origin. Moreover, it is also fair to assume there are selection processes that drive migration, something that is endemic to this type of study. For example, it could be the case that migrants who already were more positively disposed toward the native Dutch, moved to the Netherlands in greater numbers. Particularly, this applies to individuals from countries that were outside the European Union at the time of migration, due to being required to pass an exam measuring their knowledge of the Dutch language and society (Joppke, 2007).

However, even if this was the case, selection effects are not able to explain the worsening of attitudes toward the native Dutch (regardless of level of education) on the one hand, and on the other hand, the stable educational effect found toward other ethnic minorities over time. Indeed, the whole premise of the integration paradox is that better structurally- and socially-integrated migrants do not exhibit more positive attitudes toward the ethnic majority, as one would expect. Perhaps, this is due to a “honeymoon” effect, where migrants quickly become disillusioned in the host society, after a period of high spirits, due to, among other things, their low sense of belonging, their (unmet) cultural, economic and political expectations of the host society, experiencing exclusion in the host society, and feelings of attachment to their country of origin (Geurts et al., 2021).

In conclusion, these analyses reveal that higher levels of education among immigrants only have a so-called “liberalizing” effect toward subordinate groups in a host society, but not toward the ethnic majority. This sheds new light on the universality of the educational effect by delineating scope conditions to this specific phenomenon, highlighting the importance of ethnic group positions in the social hierarchy. For example, while Hagendoorn and Hraba (1987) assessed an ethnic hierarchy in the Netherlands for the first time among the native Dutch; their results show a striking resemblance with how immigrants view other groups in this study (Fig. 2), with respondents expressing the most social distance toward Turks, and the least toward Spaniards, among others. Subsequent studies have also shown that the ethnic hierarchy of the Dutch toward other ethnic groups has not changed much since the 1980’s (Hagendoorn, 1995; Hagendoorn & Pepels, 2003) with Turks and Moroccans evaluated the most negatively and Northern Europeans the most positively (Coenders et al., 2008; Verkuyten et al., 1996). This ethnic hierarchy is likely derived from the racialization of migrants from certain countries (Garner, 2007). This process of racialization of migrants is not just limited to physical features but may deem certain migrants as unassimilable due to notions of cultural incompatibility related to the idea of who constitutes a nation and national identity (Balibar, 1991; Schnapper, 1994, 1995), and who is included as a full member of society (Ivarsflaten & Sniderman, 2022; Velásquez et al., 2023). This may also explain, to some extent, why higher levels of education among Poles and Bulgarians were not associated with more positive attitudes toward Turks.

With these persistent ethnic group status hierarchies in mind, the results of the current study imply that higher levels of education has the potential to improve attitudes toward ethnic outgroups that are deemed lower in status by members of a given ethnic group. When individuals of a certain ethnic group evaluate another ethnic group similarly to theirs, or higher in status, then an educational effect is absent. Future research would benefit by investigating the possible mechanisms underpinning the integration paradox (e.g., Geurts et al., 2021, 2022), including immigrants’ negative and positive experiences (Geurts & Lubbers, 2022), as well as exploring whether these attitudes differ by educational attainment between immigrants in a receiving country and citizens in their countries of origin. This would not only shed light in the relationship between education and prejudice, but also on whether immigrants as a group are more likely to hold a particular set of attitudes as compared to those who do not migrate.

Notes

Due to the lack of a variable measuring contact with other ethnic minorities in the data, this control variable is included in analyses of both attitudes toward the ethnic majority and ethnic minorities.

References

Allport, G. W. (1954). The Nature of Prejudice. Addison-Wesley.

Alwin, D. F. (1997). Feeling thermometers versus 7-point scales: Which are better? Sociological Methods and Research, 25(3), 318–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124197025003003

Balibar, E. (1991). Racism and nationalism. In E. Balibar & I. Wallerstein (Eds.), Race, Nation, State, Class. Ambiguous Identities. (pp. 37–67). Verso.

Bobo, L., & Licari, F. C. (1989). Education and Political Tolerance : Testing the Effects of Cognitive Sophistication and Target Group Affect. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 53(3), 285–308. https://doi.org/10.1086/269154

Ceobanu, A. M., & Escandell, X. (2010). Comparative Analyses of Public Attitudes Toward Immigrants and Immigration Using Multinational Survey Data: A Review of Theories and Research. Annual Review of Sociology, 36, 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102651

Coenders, M., Lubbers, M., Scheepers, P., & Verkuyten, M. (2008). More than two decades of changing ethnic attitudes in the Netherlands. Journal of Social Issues, 64(2), 269–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.00561.x

Craig, M. A., & Richeson, J. A. (2012). Coalition or derogation? How perceived discrimination influences intraminority intergroup relations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(4), 759–777. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026481

Creighton, M. J., Capistrano, D., & da Silva Pedroso, M. (2023). Educational Mobility and Attitudes Towards Migration from an International Comparative Perspective. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 24, 817–841. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-022-00977-8

de Vroome, T., Martinovic, B., & Verkuyten, M. (2014). The integration paradox: Level of education and immigrants’ attitudes towards natives and the host society. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 20(2), 166–175. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034946

Feldman, K. A., & Newcomb, T. M. (1969). The Impact of College on Students. Transaction Publishers.

Garner, S. J. (2007). The european union and the racialization of immigration, 1985–2006. Race/Ethnicity: Multidisciplinarity Global Contexts, 1(1), 61–87.

Geurts, N., & Lubbers, M. (2022). The Good and the Bad: Do Immigrants’ Positive and Negative Evaluations of Life After Migration Go Hand in Hand? Journal of International Migration and Integration. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-022-00993-8

Geurts, N., Lubbers, M., & Spierings, N. (2020). Structural position and relative deprivation among recent migrants: A longitudinal take on the integration paradox. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(9), 1828–1848. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1675499

Geurts, N., Davids, T., & Spierings, N. (2021). The lived experience of an integration paradox: Why high-skilled migrants from Turkey experience little national belonging in the Netherlands. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(1), 69–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1770062

Geurts, N., Davids, T., Lubbers, M., & Spierings, N. (2022). A cosmopolitan explanation of the integration paradox: A mixed methods approach. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 45(16), 412–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2022.2093613

Guimond, S., Dambrun, M., Michinov, N., & Duarte, S. (2003). Does social dominance generate prejudice? Integrating individual and contextual determinants of intergroup cognitions. In Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 697–721. Turner. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.697

Guimond, S., & Palmer, D. L. (1996). The Political Socialization of Commerce and Social Science Students : Epistemic Authority and Attitude Change. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 26(22), 1985–2013. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1996.tb01784.x

Hagendoorn, L. (1995). Intergroup Biases in Multiple Group Systems: The Perception of Ethnic Hierarchies. European Review of Social Psychology, 6(1), 199–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779443000058

Hagendoorn, L., & Hraba, J. (1987). Social distance toward Holland’s minorities: Discrimination against and among ethnic outgroups. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 10(3), 317–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.1987.9993571

Hagendoorn, L., & Pepels, J. (2003). Why the Dutch maintain more social distance from some ethnic minorities than others: A model explaining the ethnic hierarchy. In W. Vollebergh, J. Veenman, & L. Hagendoorn (Eds.), Integrating Immigrants in the Netherlands: Cultural Versus Socio-Economic Integration (1st ed., pp. 41–62). Routledge.

Hainmueller, J., & Hiscox, M. J. (2007). Educated preferences: Explaining attitudes toward immigration in Europe. International Organization, 61(2), 399–442. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818307070142

Heisig, J. P., & Schaeffer, M. (2019). Why you should always include a random slope for the lower-level variable involved in a cross-level interaction. European Sociological Review, 35(2), 258–279. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcy053

Hello, E., Scheepers, P., & Gijsberts, M. (2002). Education and Ethnic Prejudice in Europe: Explanations for cross-national variances in the educational effect on ethnic prejudice. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 46(1), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830120115589

Hello, E., Scheepers, P., & Sleegers, P. (2006). Why the more educated are less inclined to keep ethnic distance: An empirical test of four explanations. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 29(5), 959–985. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870600814015

Hindriks, P., Verkuyten, M., & Coenders, M. (2014). Interminority Attitudes: The Roles of Ethnic and National Identification, Contact, and Multiculturalism. Social Psychology Quarterly, 77(1), 54–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272513511469

Hjerm, M. (2001). Education, xenophobia and nationalism: A comparative analysis. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 27(1), 37–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830124482

Hooghe, M., Meeusen, C., & Quintelier, E. (2013). The impact of education and intergroup friendship on the development of ethnocentrism. A latent growth curve model analysis of a five-year panel study among belgian late adolescents. European Sociological Review, 29(6), 1109–1121. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcs086

Hopkins, D. J., & Washington, S. (2020). The rise of trump, the fall of prejudice? tracking white americans’ racial attitudes via a panel survey, 2008–2018. In Public Opinion Quarterly, 84(1), 119–140. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfaa004

Ivarsflaten, E., & Sniderman, P. M. (2022). The Struggle for Inclusion: Muslim Minorities and the Democratic Ethos. University of Chicago Press.

Joppke, C. (2007). Beyond national models: Civic integration policies for immigrants in Western Europe. West European Politics, 30(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380601019613

Lancee, B., & Sarrasin, O. (2015). Educated Preferences or Selection Effects? A Longitudinal Analysis of the Impact of Educational Attainment on Attitudes Towards Immigrants. European Sociological Review, 31(4), 490–501. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcv008

Lubbers, M., Gijsberts, M., Fleischmann, F., & Maliepaard, M. (2018). The New Immigrant Survey – The Netherlands (NIS2NL). A four wave panel study. NWO-Middengroot, file number 420–004. DANS/EASY archive.

Martinovic, B., Van Tubergen, F., & Maas, I. (2009). Dynamics of interethnic contact: A panel study of immigrants in the Netherlands. European Sociological Review, 25(3), 303–318. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcn049

McGinnity, F., & Gijsberts, M. (2018). The experience of discrimination among newly arrived Poles in Ireland and the Netherlands. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 41(5), 919–937. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2017.1332376

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a Feather: Homophily in Social Networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 415–444.

Meeusen, C., de Vroome, T., & Hooghe, M. (2013). How does education have an impact on ethnocentrism? A structural equation analysis of cognitive, occupational status and network mechanisms. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 37(5), 507–522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.07.002

Meeusen, C., Abts, K., & Meuleman, B. (2019). Between solidarity and competitive threat?: The ambivalence of anti-immigrant attitudes among ethnic minorities. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 71, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2019.04.002

Mulders, A. M., & van Tubergen, F. (2022). The Role of Education in Native Dutch Adolescents’ Muslim Population Size Perceptions. Journal of International Migration and Integration. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-022-00995-6

Philip, C. L., Mahalingam, R., & Sellers, R. M. (2010). Understanding east indians’ attitudes toward african americans: Do mainstream prejudicial attitudes transfer to immigrants? Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 36(4), 651–671. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830903525399

Roth, W. D., & Kim, N. Y. (2013). Relocating prejudice: A transnational approach to understanding immigrants’ racial attitudes. International Migration Review, 47(2), 330–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12028

Schaeffer, M., & Kas, J. (2023). The integration paradox: A review and meta-analysis of the complex relationship between integration and reports of discrimination. International Migration Review, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/01979183231170809

Schnapper, D. (1994). The Debate on Immigration and the Crisis of National Identity. West European Politics, 17(2), 127–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402389408425018

Schnapper, D. (1995). The Idea of Nation. Qualitative Sociology, 18(2), 177–187.

Statistics Netherlands. (2019). Population; sex, age, migration background and generation. https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/en/dataset/37325eng/table?ts=1601389777887. Accessed 19 November 2020

Steinmann, J. P. (2019). The paradox of integration: Why do higher educated new immigrants perceive more discrimination in Germany? Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(9), 1377–1400. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1480359

Teije, I. T., Coenders, M., & Verkuyten, M. (2013). The paradox of integration: Immigrants and their attitude toward the native population. Social Psychology, 44(4), 278–288. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000113

Thijssen, L., Coenders, M., & Lancee, B. (2021). Ethnic Discrimination in the Dutch Labor Market: Differences Between Ethnic Minority Groups and the Role of Personal Information About Job Applicants—Evidence from a Field Experiment. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 22(3), 1125–1150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-020-00795-w

Tolsma, J., Lubbers, M., & Gijsberts, M. (2012). Education and cultural integration among ethnic minorities and natives in The Netherlands: A test of the integration paradox. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 38(5), 793–813. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2012.667994

Tuppat, J., & Gerhards, J. (2021). Immigrants’ First Names and Perceived Discrimination: A Contribution to Understanding the Integration Paradox. European Sociological Review, 37(1), 121–135. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcaa041

Van Der Zwan, R., Bles, P., & Lubbers, M. (2017). Perceived Migrant Threat among Migrants in Europe. European Sociological Review, 33(4), 518–533. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcx056

van Maaren, F. M., & van de Rijt, A. (2020). No integration paradox among adolescents. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(9), 1756–1772. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1551126

van Doorn, M., Scheepers, P., & Dagevos, J. (2013). Explaining the Integration Paradox Among Small Immigrant Groups in the Netherlands. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 14(2), 381–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-012-0244-6

Velásquez, P., & Eger, M. A. (2022). Does Higher Education Have Liberalizing or Inoculating Effects? A Panel Study of Anti-Immigrant Sentiment before, during, and after the European Migration Crisis. European Sociological Review, 38(4), 605–628. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcab062

Velásquez, P., Eger, M. A., Castañeda, H., Czymara, C. S., Ivarsflaten, E., Maxwell, R., Okamoto, D., & Wilkes, R. (2023). Processes and Pathways of Stigmatization and De-Stigmatization over Time. In L. H. Yang, M. A. Eger, & B. G. Link (Eds.), Migration Stigma: Understanding Prejudice, Discrimination, and Exclusion. Strüngmann Forum Report. MIT Press.

Velthuis, E., Verkuyten, M., & Smeekes, A. (2021). The Different Faces of Social Tolerance: Conceptualizing and Measuring Respect and Coexistence Tolerance. Social Indicators Research, 158, 1105–1125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02724-5

Verkuyten, M. (2016). The Integration Paradox: Empiric Evidence From the Netherlands. American Behavioral Scientist, 60(5–6), 583–596. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764216632838

Verkuyten, M., Hagendoorn, L., & Masson, K. (1996). The ethnic hierarchy among majority and minority youth in The Netherlands. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 26(12), 1104–1118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1996.tb01127.x

Vogt, P. W. (1997). Tolerance & education: Learning to live with diversity and difference. Sage Publications, Inc.

Weber, H. (2022). The educational divide over feelings about ethnic minorities: Does more education really lead to less prejudice? Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(1), 228–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1810540

Wodtke, G. T. (2012). The Impact of Education on Intergroup Attitudes: A Multiracial Analysis. Social Psychology Quarterly, 75(1), 80–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272511430234

Acknowledgements

The author would like to express gratitude to Marcel Lubbers and everyone at The European Research Centre on Migration and Ethnic Relations (ERCOMER) at Utrecht University for their helpful comments and suggestions, and for providing important clarifications regarding the New Immigrants Survey Netherlands data. I would also like to thank Mikael Hjerm, Maureen A. Eger, Moa Bursell, and Eva Jaspers for their useful comments at various stages of this manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Umea University. This research was supported by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (Forskningsrådet för hälsa, arbetsliv och välfärd [FORTE]) Grant No. 2016–07177, and the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet [VR]) Grant No. 2019–02996.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Paolo Velásquez is a Senior Research Assistant in the Department of Sociology at Umeå University. He earned his PhD at Umeå University in 2023, and holds a MSc. from Stockholm University and B.A. from the City College of New York. Dr.Velásquez’s current research interests are prejudice, ethnic relations, social stratification, immigrant integration, and the history of sociology. His research has been published in European Sociological Review and The American Sociologist.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Velásquez, P. Education and Inter-Ethnic Attitudes among Recent Immigrants in the Netherlands. Int. Migration & Integration 25, 109–131 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-023-01061-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-023-01061-5