Abstract

Immigration has increased as a transnational phenomenon in Europe in recent years. A total of 2.4 million people migrated to one of the EU-28 Member States during 2018 as discussed by Eurostat (2020). This new reality presents us with new challenges, barriers, and paradigms of intervention. In this context, leisure has become one of the most important tools for the inclusion of this population and the development and strengthening of civic values that are essential in these times of constant mobility and social and cultural hybridization as discussed by Ashcroft, Griffiths & Tiffin (2006). The aim of this study was to analyze the role of leisure in processes related to inclusion, improvement of life satisfaction, and those related to covering the needs of migrants. For this purpose, a questionnaire was used which was administered to 373 people from different countries of origin in the Basque Country (Northern Spain). The variables under study were participation in leisure activities, needs covered, life satisfaction, and perception of inclusion. The results indicate that the participation of these people in leisure activities and free time, their inclusion in the territory, and their perceived life satisfaction are all low, while their needs (physical, psychological, educational, social, relaxation, physiological, and artistic) are not satisfactorily covered. Furthermore, the extent to which their needs are covered, strength of the social network, inclusion, and life satisfaction all show a correlation with free time and engagement in leisure activities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Transnational migration is a significant phenomenon in Europe. A total of 2.4 million people migrated to one of the EU-28Footnote 1 Member States during 2018 (Eurostat, 2020). Leisure and spare time activities play a critical role in the processes of inclusion of ethnocultural minorities (Stodolska 2015), although its relevance is seldom contemplated by authorities and stakeholders. In this context, this research aims to analyze what is the level of participation of migrants of different origins in leisure activities, and how this participation affects their satisfaction with life and feeling of inclusion.

The phenomenon of migration has therefore become one of the major issues on the political agenda of the member states of the European Union in recent years. Most European countries have a migrant population of over 10% (Lewis & Sumit, 2017). In addition, the proportion of migrants within some countries doubled between 2002 and 2017, which has clearly had an impact on the social perception of immigration. In this context, the European Union is aware of the emergence, multiplication, and strengthening of political currents that run counter to the reception of the migrant population, all of which has hindered the processes of social or cultural inclusion of this group that is in a situation of institutional vulnerability. The EU itself has clearly become aware of this issue by stressing the need for migrants to become integrated into the increasingly intercultural societies of the twenty-seven partner countries.

At a time when discrimination, prejudice, racism and xenophobia are on the rise, there are legal, moral and economic imperatives to defend the fundamental rights, values and freedoms of the EU and to continue working towards a more cohesive society in general. The successful integration of third country nationals is a matter of common interest for all Member States (European Commission, 2016, p. 2).Footnote 2

The challenges and barriers derived from the migratory phenomenon that is currently being faced by the European Union have prompted the proposal of new intervention paradigms, since this is not only an issue related to the transnational mobility of people, but in most cases we are dealing with a pocket of the population that is in a situation of poverty and social exclusion, that cannot participate as citizens, and that suffers from ethnocultural alienation as a non-national migrant subject (Hage, 1995).

Leisure and Socio-cultural Networks as Catalysts for the Inclusion of Migrants

One important determinant of enabling the inclusion and participation of migrants is leisure, which, in the words of Stodolska (2015), plays a decisive role in the life of ethnocultural minority groups. It offers a number of important benefits, such as the establishment of intercultural and intergroup contacts, the development of opportunities for learning and cultural exchange, the strengthening of ties with the local community, the preservation of their own culture, and the benefits of physical activity for physical, mental, and social well-being (González-López et al., 2015). In a similar vein, several studies have confirmed that having a feeling of belonging to a certain community reduces the feeling of social unrest while increasing empathy, openness, and tolerance towards other people and ethnocultural groups, all of which promotes the development and strengthening of positive social interactions (McKinney, 2002; Yates & Youniss, 1996).

Stodolska and Alexandris (2004) suggest that migrants face hostile psychological and socio-cultural contexts upon arrival in host societies, and that leisure is often an effective strategy for establishing and strengthening social networks within the community itself. These ultimately facilitate the creation of more inclusive and friendly spaces for migrants, helping them to overcome the barriers they face in their new societies. In this sense, leisure activities can yield a significant number of mechanisms aimed at releasing and managing the tensions that may arise upon arrival in an unfamiliar community (Hibbler & Shinew, 2002).

The literature also indicates that leisure plays an important role in the stress management of migrants (Coleman & Iso-Ahola, 1993; Hutchinson et al. 2008; Iwasaki et al. 2013; Iwasaki & Mannell, 2000), in addition to helping both their social well-being and their overall health (Craike & Coleman, 2005; Heintzman, 2008; Iwasaki, 2008; Iwasaki et al., 2008, 2013; Kleiber et al., 2002; Newman et al., 2014).

Some of the studies mentioned above also stress the importance of the role played by leisure in dealing with situations of stigmatization and social exclusion. Participation in leisure activities plays a fundamental role in overcoming situations of social stress linked to ethnocultural issues, as well as helping to implement the development of resiliencies that help migrants to overcome any barriers they may encounter in the host society (Chung et al. 2008; Hutchinson et al., 2003; Iwasaki and Bartlett 2006).

Leisure and social networks are effective socio-cultural tools, which, during recent decades, have been consolidated as inclusion strategies not only in the general population but also in the case of migrants and refugees. The constitution of ethnocultural, linguistic, or social alliances would ultimately help migrant subjects to design and implement new life projects in the host societies. In this same line, the findings of several studies support the idea that the participation of migrant adolescents in certain activities can contribute to the development of socialization networks (Eccles & Templeton, 2002; Holland & Andre, 1987).

This correlation has also been shown in the adult population and in various international migratory contexts, which is discussed in more detail in the following section. A number of authors have also reiterated the benefits of participation in leisure activities in relation to social cohesion (Baker & Cohen, 2008; Ortega and Bayón 2014; García Roca 2004; Aranguren, 2012) and the life satisfaction of migrants (Marchesi et al., 2011; Casas & Bello, 2012).

Research has also shown differences in relation to the engagement in and access to leisure by the migrant population according to their culture and country of origin, as well as their socio-economic status. For example, in the area of the Spanish state, different investigations have shown this difference depending on migratory origin (Rodes and Rodríguez 2018; De Almeida, 2019). Various national (Camacho & Comas, 2003; Retis, 2017) and international studies have also demonstrated that access and use of leisure can differ within migrant populations of the same origin according to socio-economic variables and legal status (Schönbach et al., 2017; Sauerwein et al., 2016).

The Relationship Between Leisure and Social Networks, Inclusion, and Life Satisfaction of Migrants

In the words of Knoke (2011), social networks refer to the structural relationships formed between social actors. These are the result of connections established between individuals, subgroups, and larger groups.

There is a significant body of literature on the establishment of social networks among migrants on the European continent, many of which report the positive impact of such networks on the quality of life of this group (Bartram, 2019; Koelet et al., 2017; Voicu & Tufiş, 2017). For instance, Knight et al. (2017) analyzed the situation of Polish immigrants in the South Wales region of the UK during 2008–2012. The results obtained indicated that the decision to migrate to the host society was largely based on the social networks that were established prior to arrival, often including family and friends.

Social networks were also influential in the decision of whether to stay or leave the host society. Moreover, in another study, Liu (2013) highlighted the existence of differences between women and men when analyzing the migratory processes and movements from Senegal to France, Italy, and Spain. The results revealed that friends were the main social network through which male migrants undertook this migratory journey, while the family network carried more weight for women (Liu, 2013).

Another study conducted by Cheung and Phillimore (2017) on refugees in the UK focused on gender differences among refugees when analyzing migration patterns. These authors concluded that in the UK, social networks play a key role in reducing gender differences in terms of inclusion in the host society.

Another study by Koelet et al. (2017) highlighted the importance of having a network of family members in the host society, since the more extensive the contact with this network, the greater the likelihood of establishing a network of local friends. A recent study on the inclusion of young Romanians in Catalonia (Petreñas et al., 2019) indicated that young migrants perceive higher rates of self-identity within their ethnocultural group, although a trend towards hybridization was observed as the length of the stay in the host society increased.

Pratsinakis et al., (2015) also analyzed social networks established in several European cities and found that neighborhood-based interethnic relations were common among migrants. This study also found that these social ties did not necessarily turn into friendships, although they did provide migrants with an opportunity for socialization.

Other studies have shown, however, that migrants often lack social networks when they arrive in the host society (Bartram, 2019; Voicu and Tufiş 2017). Some of the difficulties faced by migrants upon arrival in a host country are related to the cultural shock they initially face, as well as the lack of knowledge of the language of the host country (Bartram, 2019; Brown et al., 2019; Djundeva and Ellwardt 2020; De Miguel Luken & Tranmer, 2010).

It is also important to emphasize that age is a determining factor in terms of the development and participation in social networks. Hussein (2018) highlights that older Turkish immigrants living in the UK lacked the resources necessary for active social inclusion within British society. However, social networks were shown to be key elements in providing older Turkish migrants with access to safety nets at crucial times in their lives (Hussein, 2018).

This social network of migrants is related to their life satisfaction (Joarder et al., 2017; Paloma et al., 2020), as shown by a variety of related studies conducted in different international geographic contexts and cultural groups of migrants, including Turkish and Moroccan migrants in the Netherlands (Vroome & Hooghe, 2014), migrants from the Philippines and Indonesia in Hong Kong (Leung & Tang, 2018), and migrants from different origins in Spain (Moreno-Jiménez & Hidalgo, 2011). Studies such as that conducted by Walter and Ito (2017) show how important it is for migrants to feel satisfied with their leisure activities in order to reach higher levels of life satisfaction. In our context, a study conducted with Ukrainians in Murcia yielded findings that lead to the same conclusions (Sanchez, 2007). A study of the sub-Saharan population in Germany found a relationship between subjective satisfaction in this population and positive feelings, physical exercise, improved personal relationships, and opportunities to access satisfactory leisure time. Consequently, and as stated by these authors (Adedeji and Bullinger 2019; Adedeji et al. 2019), these leisure activities can be regarded as a tool that facilitates the inclusion and subjective well-being of this population.

In a similar vein, studies conducted in various migratory contexts have identified leisure activities as a key factor in mental and physical health, as well as in life satisfaction (Kim et al., 2018a) while, conversely, non-participation in these activities is correlated with a lower level of life satisfaction (Kim et al., 2017; Stack & Iwasaki, 2009).

Thus, the objectives of this work are as follows: (1) to analyze the participation of migrants in leisure and free time, and how their psychological, educational, social, relaxation, physiological, and artistic needs are covered, along with their levels of life satisfaction and inclusion; (2) to analyze participation in leisure and free time activities according to origin and socio-economic level; and (3) to analyze if there is a correlation between leisure and free time activities, needs covered, life satisfaction, and inclusion.

Methodology

Instruments

Four evaluation instruments were used to measure the variables under study, which are described below. All the sample that participated in the study was used to measure the consistency. The internal consistency of the scales was in line with the original scales’ internal consistency.

Participation in Leisure Activities

The Kim et al. (2018b) scale was used to measure the participation in leisure activities with a strong internal consistency (c. alpha = 0.723). It is composed of four items related to participation in intellectual, physical, psychological, and social activities.

Needs Covered

We used Beard and Ragheb’s (1980) 6-item scale that measures how frequently leisure and free time activities cover psychological, educational, social, relaxation, physiological, and artistic needs. The scale has a strong internal consistency (c. alpha = 0.756).

Life Satisfaction

Diener et al. (1985) 5-item scale measuring life satisfaction was used. The scale has a strong internal consistency (c. alpha = 0.876).

Perception of Inclusion

We used the pictorial scale of Woosnam (2010), which uses drawings to indicate the degree of perceived inclusion. The scale has a strong internal consistency (c. alpha = 0.693).

Sample

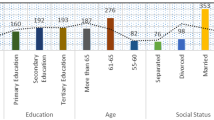

The sample consisted of 373 immigrants aged between 18 and 65 years, with a mean age of 32.89 years (SD = 11.47). Of the sample, 49.9% were men (n = 187) and 49.6% were women (n = 186). In terms of origin, 47.7% were from Latin America (n = 178), 23.1% from Eastern Europe (n = 86), 21.7% from Africa (n = 82), 4.6% from Asia (n = 17), and 2.4% (n = 9) from Central Europe. With regard to academic, their academic level 34.31% have a bachelor’s degree (n = 117), 28.73% have secondary studies (n = 98), 18.76% has university studies (n = 64), and 18.18% has primary studies. In relation to the economic situation, most of the participants were unemployed 25.5% (n = 87) or 32.2% specialized workers (like plumber, electrician…) (n = 110), 12.6% housework workers (n = 43), 12% were higher degree graduates (teacher, lawyer…) (n = 41), and 11.1% construction workers or pawns (n = 38). Finally, only 5.6% were business man or woman of a company with less than 25 employees (n = 19) and 1.2% were business man or woman of a company with more than 25 employees (n = 4).

Procedure

Data Analysis and Procedure

The questionnaire was administrated in English in case that they speak English and in the other case, it were translated to Spanish or French with good internal consistency. The responders need 30 min to complete the questionnaire. First, consent was given to analyze the data and second, to make the data public in scientific articles while respecting anonymity.

For this study, descriptive statistics of the variables studied (leisure and free time activities, needs covered, life satisfaction, and inclusion) were presented through the analysis of means. Likewise, analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and post hoc analysis through the Tukey test were used to explore the differences between variables according to participation in leisure and free time activities and origin and socio-economic level. Subsequently, Pearson’s correlation analyses were conducted among the three main variables of this study, i.e., participation in leisure activities, needs met, and life satisfaction and inclusion. Data analyses were conducted with the Statistics Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Version 24).

Results

Leisure Activities, Needs Covered, and Life Satisfaction and Inclusion

The means of the variables under study (leisure and free time activities, needs covered, life satisfaction, and inclusion) were analyzed (Table 1).

The data indicate that the means are below the median cut-off point (M = 2.5) in the case of leisure activities and covered needs. With respect to satisfaction with life (M = 3.44), it is observed that the means are higher, being slightly above the cut-off point, but in intermediate positions.

Likewise, with respect to inclusion, the immigrants analyzed are placed in the position of diagram c (M = 3.93) (Fig. 1).

C diagram in scale of Woosnam (2010), degree of perceived inclusion

Leisure Activities and Country of Origin

One-factor ANOVAS were conducted to analyze whether there are differences between participation in leisure and free time activities according to the country of origin (Table 2).

The data show that there are no significant differences regarding the amount of time spent engaged in leisure activities and free time according to country of origin. However, the data indicate that the means are higher for people from Central Europe (M = 2.61), followed by Eastern Europe (M = 2.30) compared with those of the other countries of origin: Africa (M = 2.18), Latin America (M = 2.19), and Asia (M = 2.02).

Leisure Activities and Socio-economic Level

One-factor ANOVAS were conducted to analyze whether there are differences in the leisure activities and free time undertaken by immigrants according to socio-economic level (Table 3).

The data indicate that there are differences in time spent engaged in leisure and free time activities according to socio-economic level. The immigrants with a high socio-economic level show higher participation in these activities (M = 2.46), followed by those with a medium socio-economic level (M = 2.26) while those of a low socio-economic level have the lowest mean (M = 2.06).

Correlations Between Leisure and Coverage of Needs, Satisfaction with Life, and Inclusion

Correlation analyses were conducted between the study variables to analyze if there is a relationship between them (Table 4).

Inspection of Table 4 shows that there is a correlation between time spent on leisure and free time activities and the rest of the variables analyzed. There is a correlation, from highest to lowest, between leisure activities and life satisfaction (r = 414), needs covered (r = 3.76), inclusion (r = 3.42), and social network (r = 0.331).

Discussion and Conclusions

The present study had three main objectives: (1) to analyze the extent to which immigrants participate in leisure and free time activities and the coverage of their psychological, educational, social, relaxation, physiological, and artistic needs, along with their satisfaction with life and inclusion; (2) to analyze time spent on leisure and free time activities according to origin and socio-economic level; and (3) to examine if there is a correlation between time spent on leisure activities and free time, coverage of needs, satisfaction with life, and inclusion.

First, we can conclude that participation in leisure and free time activities in the analyzed sample is low. Furthermore, the psychological, educational, social, relaxation, physiological, and artistic needs are not covered in a satisfactory way through leisure and free time. This suggests that the participation of the immigrant population in leisure and free time activities is scarce, while their basic needs are not satisfactorily covered. Moreover, their perceived levels of inclusion and life satisfaction are low. Previous studies have highlighted the determining role played by leisure and free time in the establishment of intercultural and intergroup contacts, and in physical, psychological, mental, and social well-being (González-López et al., 2015). In this regard, a significant number of experts also suggest that leisure plays a decisive role in the processes of inclusion of ethnocultural minorities (Stodolska 2015).

The immigrants analyzed in this study also perceive their social networks to be vulnerable or fragile, that is, they do not have an extensive social network. Various studies have also shown how immigrants lack such networks upon their arrival and during the first years spent in the host society (Bartram, 2019; Voicu & Tufiş, 2017) and how this has a negative impact on their quality of life and inclusion process.

Various investigations have also confirmed the need to legitimize socio-cultural practices in leisure and free time as a fundamental element for the recovery and identification process of the community or as a tool for addressing emergent social-educational problems (Holden, 2006; Casacuberta et al. 2011).

Second, we can note that although there are no significant differences with respect to the practices of leisure and free time carried out according to the origin of the immigrants, it appears that migrants from European countries engage in a greater number of leisure and free time activities. In contrast, those originating from Asia report a lower level of participation in leisure and free time activities. Previous studies have reported these differences between migratory communities and highlight the importance of taking these into account when designing interventions in this area (Bernal and Sáez-Santiago 2006).

Third, the data indicate that socio-economic level is an important factor in the enjoyment of leisure and free time, since those who have greater purchasing power appear to engage more in leisure and free time activities. The importance of socio-economic level has also been highlighted in previous studies (Schönbach et al. 2017; Sauerwein et al. 2016) and has particularly been identified as a barrier to accessing leisure activities in this population (Stodolska & Santos, 2006).

Finally, the data of our study suggest that there is a correlation between the enjoyment of leisure and free time and the coverage of needs, satisfaction with life, and inclusion. Thus, it appears that free time is of importance for immigrants and contributes to improving their lives, meeting their most basic needs, and facilitating their inclusion in the host community. The findings of other research studies also support this view, showing how participation in leisure and free time activities can help social cohesion (Ortega and Bayón 2014; García Roca 2004; Aranguren, 2012) as well as their inclusion (Blomfield & Barber, 2011; Brown & Evans, 2002; Marsh & Kleitman, 2003). In this regard, various authors have also concluded that socio-cultural and leisure practices contribute to the improvement of social cohesion, which, in turn, significantly enhances the quality of life of the people and their communities (Marchesi et al. 2011; Casas & Bello, 2012).

The low participation in leisure activities and free time in the sample analyzed here is rather worrying. Given the importance of these activities for the inclusion and improvement of the quality of life of people, as well as for their psychological and social development, it will be necessary to continue designing programs that ensure the inclusion of immigrants in socio-educational projects within the framework of leisure and free time spaces. In this regard, it is also important, as indicated in the literature (Horolets 2012) to identify the various difficulties that migrants have in accessing leisure and put in place the necessary measures to overcome such problems.

This study, however, has certain limitations. First, the use of a convenience sample makes it impossible to generalize the results. Second, the sample size is limited. Thus, in the future, it would be of interest to conduct a more extensive investigation with a larger sample size.

Data availability

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Code Availability

Any custom software or application code supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The project was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU), (M10/2020/055).

Notes

The EU-28 is the abbreviation of European Union (EU) which consists a group of 28 countries (Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Estonia, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Croatia, Italy, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Hungary, Malta, Netherlands, Austria, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Finland, Sweden, UK) that operates as an economic and political block.

Authors’ translation.

References

Adedeji, A., & Bullinger, M. (2019). Subjective integration and quality of life of sub-Saharan African migrants in Germany. Public Health, 174, 134–144.

Adedeji, A., Silva, N., & Bullinger, M. (2019). Cognitive and structural social capital as predictors of quality of life for Sub-Saharan African migrants in Germany. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 1–15.

Aranguren, L. (2012). Voluntariado, educación y ciudadanía [Volunteering, education and citizenship]. Revista D’educació Social, 50, 102–112.

Baker, S., & Cohen, B. (2008). From snuggling and snogging to sampling and scratching: Girls’ nonparticipation in community-based music activities. Youth and Society, 39(3), 316–339.

Bartram, D. (2019). Sociability among European migrants. Sociological Research Online, 24(4), 557–574.

Beard, J. G., & Ragheb, M. G. (1980). Measuring leisure satifaction. Journal of Leisure Research, 12(1), 20–33.

Bernal, G., & Sáez-Santiago, E. (2006). Culturally centered psychosocial interventions. Journal of Community Psychology, 34(2), 121–132.

Blomfield, C., & Barber, B. (2011). Developmental experiences during extracurricular activities and Australian adolescents’ self-concept: Particularly important for youth from disadvantaged schools. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(5), 582–594.

Brown, R., & Evans, W. P. (2002). Extracurricular activity and ethnicity: Creating greater school connection among diverse student populations. Urban Education, 37(1), 41–58.

Brown, K., Adger, W. N., Devine-Wright, P., Anderies, J. M., Barr, S., Bousquet, F., ... & Quinn, T. (2019). Empathy, place and identity interactions for sustainability. Global environmental change, 56, 11-17.Camacho, J.M. y Comas, D. (2003). El ocio y los jóvenes inmigrantes [Leisure and young immigrants]. Injuve, 60, 11-18

Camacho, J. M., y Comas, D. (2003). El ocio y los jovenes inmgrantes, in Cachon, L. Inclusión de la juventud Inmgrate. Injuve. 73–80.

Casas, F., & Bello, A. [Coord.] (2012). Calidad de Vida y Bienestar Infantil Subjetivo en España. ¿Qué afecta al bienestar de niños y niñas españoles de 1º de ESO? UNICEF España. Madrid.

Casacuberta, D., Rubio, N. & Serra, S. S. (2011). Acción cultural y desarrollo comunitario [Cultural action and community development]. Graó.

Cheung, S. Y., & Phillimore, J. (2017). Gender and refugee integration: A quantitative analysis of integration and social policy outcomes. Journal of Social Policy, 46(2), 211–230.

Chung, R. C. Y., Bemak, F., Ortiz, D. P., & Sandoval-Perez, P. A. (2008). Promoting the mental health of immigrants: A multicultural/social justice perspective. Journal of Counseling & Development, 86(3), 310–317.

Coleman, D., & Iso-Ahola, S. E. (1993). Leisure and health: The role of social support and self-determination. Journal of Leisure Research, 25(2), 111–128.

Craike, M. J., & Coleman, D. J. (2005). Buffering effects of leisure self-determination on the mental health of older adults. Leisure/loisir, 29(2), 301–328.

De Almeida, R. C. P. (2019). Ocio como ámbito de integración de inmigrantes: Representaciones y vivencias de mujeres brasileñas en el País Vasco [Leisure as a sphere of integration of immigrants: Representations and experiences of Brazilian women in the Basque Country]. Revista Subjetividades, 19(2), 1–15.

De Miguel Luken, V., & Tranmer, M. (2010). Personal support networks of immigrants to Spain: A multilevel analysis. Social Networks, 32(4), 253–262.

Djundeva, M., & Ellwardt, L. (2020). Social support networks and loneliness of Polish migrants in the Netherlands. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(7), 1281–1300.

Diener, E., Emmons, R., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Eccles, J. S., & Templeton, J. (2002). Chapter 4: Extracurricular and other after-school activities for youth. Review of Research in Education, 26(1), 113–180

European Commission. (2016). Action plan on the integration of third country nationals. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/legal-migration/integration/action-plan-integration-third-country-nationals_en. Accessed 17 Apr 2020.

Eurostat. (2020). Estadísticas de migración y población migrante [Migration statistics and migrant population]. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Migration_and_migrant_population_statistics/es#Flujos_migratorios:_En_2018.2C_la_inmigraci.C3.B3n_en_la_EU-27_desde_terceros_pa.C3.ADses_fue_de_2.2C4_millones. Accessed 17 Apr 2020.

García Roca, J. (2004). Políticas y programas de participación social [Social participation policies and programs.]. Síntesis

González-López, J. R., Rodríguez-Gázquez, M., & Lomascampos, M. (2015). Physical activity in Latin American immigrant adults living in Seville. Spain, Nursing Research, 64(6), 476–484.

Hage, G. (1995). The spatial imaginary of national practices: Dwelling-domesticating / being-exterminating. Sydney University.

Heintzman, P. (2008). Leisure-spiritual coping: A model for therapeutic recreation and leisure services. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 42(1), 56.

Hibbler, D., & Shinew, K. (2002). Interracial couples’ experience of leisure: A social network approach. Journal of Leisure Research, 34(2), 135–156.

Holden, J. (2006). Cultural value and the crisis of legitimacy. Demos.

Holland, A., & Andre, T. (1987). Participation in extracurricular activities in secondary school: What is known, what needs to be known? Review of Educational Research, 57(4), 437–466.

Horolets, A. (2012) Migrants’ leisure and integration. Institute of Public Affairs.

Hutchinson, S. L., Loy, D. P., Kleiber, D. A., & Dattilo, J. (2003). Leisure as a coping resource: Variations in coping with traumatic injury and illness. Leisure Sciences, 25(2–3), 143–161.

Hutchinson, S. L., Bland, A., & D. & Kleiber, D. A. (2008). Is leisure beneficial for older Korean immigrants? An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 42(1), 9–23.

Hussein, S. (2018). Work engagement, burnout and personal accomplishments among social workers: A comparison between those working in children and adults’ services in England. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 45(6), 911–923.

Iwasaki, Y. (2008). Pathways to meaning-making through leisure-like pursuits in global contexts. Journal of Leisure Research, 40(2), 231–249.

Iwasaki, Y., & Bartlett, J. G. (2006). Culturally meaningful leisure as a way of coping with stress among aboriginal individuais with diabetes. Journal of Leisure Research, 38(3), 321–338.

Iwasaki, Y., Bartlett, J., MacKay, K., Mactavish, J., & Ristock, J. (2008). Mapping nondominant voices into understanding stress-coping mechanisms. Journal of Community Psychology, 36(6), 702–722.

Iwasaki, Y., Coyle, C., Shank, J., Messina, E., & Porter, H. (2013). Leisure-generated meanings and active living for persons with mental illness. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 57(1), 46–56.

Iwasaki, Y., & Mannell, R. C. (2000). Hierarchical dimensions of leisure stress coping. Leisure Sciences, 22(3), 163–181.

Joarder, M. A. M., Harris, M., & Dockery, A. M. (2017). Remittances and happiness of migrants and their home households: Evidence using matched samples. The Journal of Development Studies, 53(3), 422–443.

Kim, J., Lee, S., Chun, S., Han, A., & Heo, J. (2017). The effects of leisure-time physical activity for optimism, life satisfaction, psychological well-being, and positive affect among older adults with loneliness. Annals of Leisure Research, 20(4), 406–415.

Kim, J., Heo, J., Dvorak, R., Ryu, J., & Han, A. (2018a). Benefits of leisure activities for health and life satisfaction among western migrants. Annals of Leisure Research, 21(1), 47–57.

Kim, E., Kleiber, D. A., & Kropf, N. (2018b). Leisure activity, ethnic preservation, and cultural integration of older Korean Americans. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 36, 107–129.

Kleiber, D. A., Hutchinson, S. L., & Williams, R. (2002). Leisure as a resource in transcending negative life events: Self-protection, self-restoration, and personal transformation. Leisure Sciences, 24(2), 219–235.

Knight, J., Thompson, A., & Lever, J. (2017). Social network evolution during long-term migration: A comparison of three case studies in the South Wales region. Social Identities, 23(1), 56–70.

Knoke, D. (2011). Social networks. Oxford University Press.

Koelet, S., Van Mol, C., & De Valk, H. A. (2017). Social embeddedness in a harmonized Europe: The social networks of European migrants with a native partner in Belgium and the Netherlands. Global Networks, 17(3), 441–459.

Leung, D. D. M., & Tang, E. Y. T. (2018). Correlates of life satisfaction among Southeast Asian foreign domestic workers in Hong Kong: An exploratory study. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, 27(3), 368–377.

Lewis, D., & Sumit, S. (2017). Immigration and the rise of far right parties in Europe. Universität München.

Liu, M. M. (2013). Migrant networks and international migration: Testing weak ties. Demography, 50(4), 1243–1277.

Marsh, H. W., & Kleitman, S. (2003). School athletic participation: mostly gain with little pain. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 25(2).

McKinney, K. G. (2002). Engagement in community service among college students: Is it affected by significant attachment relationships? Journal of Adolescence, 25(2), 139–154.

Marchesi, A., Tedesco, J. C. & Coll, C. (2011). Calidad, equidad y reformas en la enseñanza [Quality, equity and reforms in education]. Santillana.

Moreno-Jiménez, M. P., & Hidalgo, C. M. (2011). Measurement and prediction of satisfaction with life in immigrant workers in Spain: Differences according to their administrative status. Anales De Psicología, 27(1), 179–185.

Newman, D. B., Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2014). Leisure and subjective well-being: A model of psychological mechanisms as mediating factors. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(3), 555–578.

Ortega, C. & Bayón, F. (2014). El papel del ocio en la construcción social del joven [The role of leisure in the social construction of young people]. Documentos de Estudios de ocio.

Paloma, V., Escobar-Ballesta, M., Galván-Vega, B., Díaz-Bautista, J. D., & Benítez, I. (2020). Determinants of life satisfaction of economic migrants coming from developing countries to countries with very high human development: A systematic review. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 1–21.

Petreñas, C., Ianos, A., Sansó, C., & Huguet, Á. (2019). The inclusion process of young Romanians in Catalonia (Spain): The relationship between participating in classes of L1, self-identification, and life-satisfaction. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 40(10), 920–933.

Pratsinakis, M., Vogiatzis, N., Labrianidis, L., & Hatziprokopiou, P. A. (2015). Living together in multi-ethnic cities. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki.

Retis, J. (2017). ¿ Consumidores o ciudadanos? Prácticas de consumo cultural de los inmigrantes latinoamericanos en España [Consumers or citizens? Cultural consumption practices of Latin American immigrants in Spain]. Comunicação, Mídia e Consumo, 14(41), 53.

Rodes, J., & Rodríguez, V. (2018). Migrantes de retiro en España: Estilos de vida multilocales y patrones de integración [Retirement migrants in Spain: Multilocal lifestyles and integration patterns]. Migraciones Internacionales, 9(3), 193–222.

Sanchez, A. (2007). Inmigración, necesidades y acceso a los servicios y recursos: Los inmigrantes ucranianos en los procesos de inserción en la comunidad autónoma de Murcia [Immigration, needs and access to services and resources: Ukrainian immigrants in the processes of insertion in the autonomous community of Murcia.]. Universidad de Murcia.

Sauerwein, M., Theis, D., & Fischer, N. (2016). How youths’ profiles of extracurricular and leisure activity affect their social development and academic achievement. IJREE–International Journal for Research on Extended Education, 4(1).

Schönbach, J. K., Pfinder, M., Börnhorst, C., Zeeb, H., & Brand, T. (2017). Changes in sports participation across transition to retirement: Modification by migration background and acculturation status. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(11), 1356.

Stack, J. A., & Iwasaki, Y. (2009). The role of leisure pursuits in adaptation processes among Afghan refugees who have immigrated to Winnipeg. Canada. Leisure Studies, 28(3), 239–259.

Stodolska, M. (2015). Recreation for all: Providing leisure and recreation services in multi-ethnic communities. World Leisure Journal, 57(2), 89–103.

Stodolska, M., & Alexandris, K. (2004). The role of recreational sport in the adaptation of first generation immigrants in the United States. Journal of Leisure Research, 36(3), 379.

Stodolska, M., & Santos, C. A. (2006). Transnationalism and leisure: Mexican temporary migrants in the US. Journal of Leisure Research, 38(2), 143–167.

Voicu, B., & Tufiş, C. D. (2017). Migrating trust: Contextual determinants of international migrants’ confidence in political institutions. European Political Science Review, 9(3), 351–373.

Vroome, T., & Hooghe, M. (2014). Life satisfaction among ethnic minorities in the Netherlands: Immigration experience or adverse living conditions? Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(6), 1389–1406.

Woosnam, K. M. (2010). The inclusion of other in the self (IOS) scale. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(3), 857–860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2010.03.003

Yates, M., & Youniss, J. (1996). Community service and political identity. Development in adolescence. Journal of Social Issues, 54(3), 495–512.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. This research was supported by the KideOn Research Group of the Basque Government, Ref.: IT1342-19 (A category).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Berasategi Sancho, N., Roman Etxebarrieta, G., Alonso Saez, I. et al. Leisure as a Space for Inclusion and the Improvement of Life Satisfaction of Immigrants. Int. Migration & Integration 24, 425–439 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-021-00917-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-021-00917-y