Abstract

If a person is overqualified in the sense that an employee’s level of training exceeds the job requirements, then some human capital lies idle and cannot be converted into appropriate (monetary and non-monetary) returns. Migrants are particularly at risk of being overqualified in their employment; however, this phenomenon cannot be fully explained by differences in human capital or socio-economic characteristics. This paper examines whether social capital plays a decisive role in migrants’ risk of overqualification in Germany. Using data from the German IAB-SOEP Migration Sample, we analyse the job search process of migrants to determine whether social networks influence their risk of being employed below their acquired educational level. We estimate logistic regression models and find that social capital influences the adequacy of migrants’ jobs: We show that migrants are at a greater risk of overqualification if they use only informal job search strategies such as relying on friends or family members. Moreover, we find that homophilous migrant networks and jobs in employment niches are risk factors for overqualification. We conclude that the combination of informal job search modes and homophilous migrant networks leads to a comparably high risk for migrants of being overqualified in their employment in the German labour market.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A large body of empirical research has shown that migrants face difficulties when attempting to integrate into their host countries’ labour markets. On the one hand, there are general difficulties in gaining employment, which are particularly reflected in migrants’ lower labour market participation and employment rates (Seibert, 2011; Eurostat, 2011). On the other hand, migrants have smaller shares of qualified jobs in high-status occupations (Constant & Massey, 2005; Granato & Kalter, 2001; Simón et al., 2008); thus, they tend to obtain lower wages relative to those of natives (Aldashev et al., 2012). Another important aspect of (successful) labour market integration is an employee’s educational suitability for a job. If an employee’s level of education and qualification exceeds the requirements of the job, then the employee is overqualified for the job. Consequently, overqualificationFootnote 1 implies that the human capital acquired through the education system cannot be utilised in its entirety and cannot be converted into appropriate (monetary or non-monetary) returns (Büchel, 2001; McGuinness, 2006; Pollmann-Schult & Büchel, 2002).Footnote 2

National and international studies show that migrants are a high-risk group for overqualified employment (Battu & Sloane, 2004; Joona et al., 2014; Kracke, 2016; Piracha et al., 2012). The explanations for migrants’ conspicuous vulnerability to overqualification discussed in the literature focus on the imperfect transferability of human capital (Chiswick & Miller, 2009; Piracha & Vadean, 2013), pre-migration overqualification (Kalfa & Piracha, 2013; Piracha et al., 2012) and discrimination (Battu & Sloane, 2004; McGuinness & Byrne, 2015; McGuinness & Sloane, 2011; Rafferty, 2012). However, the available literature cannot fully explain migrants’ disadvantages in occupational attainment based on differences in human capital, socio-economic characteristics or discriminatory conduct.

From a sociological perspective, it has been repeatedly argued that social capital can influence the transferability of human capital across national borders and human capital investments in the host country (Borjas, 1990; Thomsen, 2010).Footnote 3 For example, empirical results have shown that migrants’ social networks influence their overall labour force participation (Aguilera, 2002; Kalter & Kogan, 2014), their wages immediately after migration and subsequent wage adjustments (Aguilera & Massey, 2003; Goel & Lang, 2009; Romiti et al., 2015).

Nevertheless, empirical evidence regarding the relationship between social capital and overqualification is scarce. In general, social capital has been shown to influence the adequacy of employment; however, the prior findings are mixed and do not provide a clear direction (regarding the positive impact of social capital on adequate employment, see Franzen and Hangartner (2005); regarding the negative impact, see Weiss and Klein (2011)). In the case of migrants, associational involvement in the host country has been found to reduce the risk of overqualification (Griesshaber & Seibel, 2015); however, living in regions with high ethnic concentrations, which is associated with co-ethnic social contact, has been shown to increase migrants’ risk of overqualification (Kalfa & Piracha, 2015). A recent publication additionally shows that migrants (migrating from Central Eastern to Western European countries) who have found their jobs through social networks are more prone to overqualification (Leschke & Weiss, 2020).

To date, however, the process of searching for a jobFootnote 4 has not been considered in conjunction with migrants’ risk of overqualification for Germany. Therefore, whether migrants’ networks have a direct influence on the adequacy of their jobs is concealed. This study aims to address this deficit and contributes to the literature by answering the following research questions for the GermanFootnote 5 context: Is social capital, activated during the job search process, related to migrants’ particular risk of being overqualified in their employment? Are migrants, who rely on social resources while searching for a job, more likely to be overqualified for their job than those who use formal methods of job search? Is there a link between overqualification and being employed in migrant employment niches?

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to explicitly analyse for Germany the role of migrants’ social network characteristics during the job search process and whether and how they are linked to migrants’ job adequacy. This particular aspect must be examined to determine the optimal types of job search strategies for migrants to avoid overqualification and, thus, to receive appropriate returns on their educational investments.

Impact of social capital on migrants’ overqualification

Overqualification exists if the qualifications and skills acquired in education and training exceed the requirements of the occupation held in the labour market. Accordingly, investments in education cannot be entirely utilised and converted into appropriate returns. The risk of being overqualified varies based on diverse determinants such as gender, social background, and, as previously outlined, migration background (Battu & Sloane, 2004; Erdsiek, 2016; Joona et al., 2014; Kracke, 2016). Therefore, the consequences of overqualification are concentrated on certain social groups and (re-)produce social inequalities in societies. Consistent with the general consequences of overqualification, the labour market performance of overqualified migrants is characterised by wage penalties and a lower probability of job satisfaction (Kalfa & Piracha, 2013; McGuinness & Byrne, 2015). Additionally, some studies show more pronounced negative impacts due to overqualification e.g. higher wage losses and higher degrees of persistence, among migrants than among natives (Joona et al., 2014; Nielsen, 2011).

Regarding the theoretical explanations for the phenomenon of overqualification in general, various existing labour market theories are used in the sociological and economic literature. However, a unified theory explaining how the phenomenon of overqualification can be conceptualised is lacking. From different perspectives (individual versus structural approaches or employee versus employer perspectives), attempts have been made to theoretically grasp and explain the phenomenon. The arguments that are mostly used include those based on human capital theory (Becker, 1962), the job competition model (Thurow, 1975), signal theory (Spence, 1973), and search and matching theories (Jovanovic, 1979).Footnote 6 However, none of these theoretical arguments can explain why migrants are particularly vulnerable to overqualification. Explaining this phenomenon requires individualistic approaches with arguments related to theories concerning social inequality, which extend beyond human capital factors and socio-economic characteristics. As stated above, in the case of migration, it has been shown that social capital can influence the transferability of human capital.

The social resources approach defines social capital as “the wealth, status, power, as well as social ties of those persons who are directly or indirectly linked to the individual” (Lin et al., 1981, p. 1163). Burt (2000) refers to the topic of social capital as “a metaphor about advantage” because available relationships are social capital. If an individual is connected to several social contacts, such as family members, friends or colleagues, a social network is formed.

In meritocratic societies, social networks should not be relevant. However, Lin et al. (1981) argue that social resources undermine Blau and Duncan’s (1967) hypothesis regarding the “importance of education for occupational attainment” (de Graaf & Flap, 1988, p. 454) as the resources used during the job search process also affect the occupational status attained. This claim is supported by the prior research showing that the type of job search leads to different types of jobs and outcomes (Lin et al., 1981; Weiss & Klein, 2011). Similarly, Granovetter (1973) notes that the utilisation of social capital leads to shorter job searching periods and more information regarding job fit or vacancies since social networks enable individuals to gain more job-relevant information compared to their unconnected counterparts. Consequently, not only do these information advantages help by providing information about job vacancies, but they can also be used to ascertain whether a job is suitable in terms of particular dimensions such as the formal qualifications level and wages (Granovetter, 1973; Mouw, 2003). Thus, these advantageous informal job searches can be a way of accessing positions based on an individual’s qualification level and thus may diminish the risk of overqualification.

In the case of migrants, social contacts constitute an especially important tool that can help them integrate into the host country’s labour market and thereby find jobs. For instance, it has been shown that migrants more frequently accept jobs found via informal job search channels, such as friends or relatives, compared to those found via formal channels such as employment agencies (Drever & Hoffmeister, 2008).

However, a network’s effectiveness can be undermined by the social mechanism of homophilyFootnote 7 (Mouw, 2006), which describes a favoured “interaction with others who have similar given attributes such as sex, race, and education” (Ibarra, 1992). The previous research has shown that similar individuals tend to “flock together” in various areas of their social lives (e.g. McPherson et al., 2001; Kossinets & Watts, 2009) and that different outcomes facilitated by social capital vary depending on the composition of the group e.g. ethnic minority status or educational level (Lin, 2000; Klug, 2018).

Thus, homophily influences the types of social resources that can be utilised. According to this assumption and because social capital is geographically bound to the people who constitute an individual’s network (DaVanzo, 1981), host-country social capital can be distinguished from country-of-origin social capital. The former is assumed to be related to natives while the latter is assumed to be related to migrants (Haug, 2003; Heizmann & Böhnke, 2016). Information regarding jobs, the functioning of labour markets, and job application procedures and strategies are specific to the host country (Kalter, 2006); therefore, ties to natives help migrants to gain access to job opportunities and to obtain knowledge regarding how to land on adequate jobs. An exclusive reliance on country-of-origin social capital is thus a particular handicap for migrants who seek to find a well-matched labour market position in their host country (Colic-Peisker & Tilbury, 2006; Korac, 2005; Ahmad, 2015).Footnote 8

Therefore, homophily is related to migrants’ inability to exploit the information advantages and influences that should accompany social capital (Colic-Peisker & Tilbury, 2006). Hence, we must consider the ethnic homogeneity of migrants’ networks to more accurately predict the influence of informal job searches on their risk of overqualification. Thus, the informal search methods of migrants with a high proportion of homophilous ties are likely less effective than those of migrants with ties to individuals with host-country social capital. Thus, we predict the following:

H1a:Migrants with homophilous migrant networks are at a higher risk of overqualification than migrants with heterophilous migrant/native networks.

H1b: Migrants with homophilous migrant networks who use informal job search strategies rather than formal strategies have the highest risk of overqualification.

Labour market segments with high concentrations of migrants are known as employment niches. The empirical literature has shown that employment in such niches is considered to be a risk factor with regard to labour market success because such jobs are often in low-paid secondary sectors that require lower qualification levels (Colic-Peisker & Tilbury, 2006; Constant & Massey, 2005; Simón et al., 2008). We thus conclude that jobs in such employment niches are also a risk factor in terms of the adequacy of employment. The literature also discusses that such niches arise because either migrants’ skills match such jobs better than those of natives or they are funnelled into low-skilled jobs (Moya, 2007; Waldinger, 1994). In this regard, these types of jobs can be considered to be a better alternative than being unemployed. Alternatively, it is possible that migrants prefer jobs in homogeneous working environments and consider overqualification to be a trade-off. Irrespective of whether it is a stepping stone or a trap, we focus on the connection between being employed in such a niche and the risk of overqualification.

One indicator of being employed in such an employment niche is the proportion of work colleagues with a migration background. We assume that those who have a particularly high share of colleagues with a migration background are employed in employment niches and in turn (due to the typical characteristics of jobs in employment niches) have a higher risk of not being employed adequately to their education level. We therefore hypothesise the following relationship:

H2: A positive relationship exists between a high proportion of migrant co-workers and the risk that an individual will be overqualified in his or her employment.

Research design

Data, sample restrictions and method

The empirical analysis is based on the first two waves of the German IAB-SOEP Migration Sample conducted in 2013 and 2014,Footnote 9 a joint panel survey of migrants living in Germany by the Institute for Employment Research (IAB) and the Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) at the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW).Footnote 10 The sample is drawn from migrants who either immigrated themselves or who are the children of immigrants and who registered with the German Federal Employment Agency for the first time after 1995.Footnote 11 This survey offers a wide range of information concerning migration, education and labour market biographies related to the country of origin, Germany and all other countries where the migrants have lived. Additionally, rich information concerning social networks, job searches, socio-economic status, family situations and working conditions are included. The individuals in the sample were surveyed via computer-assisted personal interviews (CAPI) in which it was possible to choose among the languages German, English, Polish, Turkish, Romanian and Russian.

Our analysis is restricted to migrants (born abroad) who did not attend school and/or participate in training exclusively in Germany, thereby excluding those who immigrated at young ages who grew up and were socialised and educated exclusively or mainly in Germany. We also exclude migrants who migrated to Germany as an employed person with an existing job offer. This group might differ from and, therefore, be more selective than other migrants because the former were embedded in German labour market structures since migration and thus may have different access to social networks. Moreover, to adequately measure overqualification, we select only persons in paid and dependent employment and exclude trainees/apprentices, the self-employed and retirees. Individuals whose foreign credentials have not been recognised in Germany are also excluded from the analyses. It is not possible to explicitly measure their level of actual and usable training as their degrees obtained abroad are not usable on the German labour market. We further restrict our sample to persons who have qualification levels comparable to vocational training due to too few cases of persons with university degrees.Footnote 12

To examine the impact of social capital during job search periods on the dependent variable i.e. migrants’ risk of overqualification, multivariate analyses are conducted using binary logistic regressions.Footnote 13 To ensure the comparability of the different models, the average marginal effects (AMEs) are shown as estimated results (Best & Wolf, 2010). To test our hypotheses, interaction terms are partially required. In contrast to linear models, in non-linear models, the first derivation of the interaction effects cannot be used for the interpretation of interactions (Buis, 2010; Cornelißen & Sonderhof, 2009). For this reason, and because the statistical significance of the interaction effects cannot be measured with a t-test based on the coefficient of the interaction term (Ai & Norton, 2003), the following procedure is used to interpret the interaction effects. Based on the overall model, the AMEs of each combination of the respective interactions are calculated. The difference in these marginal effects represents the direct marginal effect of the interaction i.e. the variation between the individual groups (delta method). A Wald test is used to calculate the corresponding significance.

Variables and descriptive results

Excursus to the measurement of overqualification and dependent variable

If the qualification level an employee acquired in education and training differs from that required by the occupation held in the labour market, the employee is not adequately employed. Hence, there is a mismatch between the job and the employee. If the acquired credentials outperform the required credential, this situation is referred to as overqualification.Footnote 14 An often-used example is the trope of the taxi-driving academic or a trained baker who works in a factory where no training is required.

In recent decades, much effort has been made to measure overqualification and other concepts of labour market mismatch; however, to date, no standard practice has been established (Verhaest & Omey, 2006). Nevertheless, certain procedures are widely used in empirical studies. The most important procedures can be subsumed under the headings of subjective (Büchel, 1998, 2001; Kracke, 2016; Di Stasio et al., 2016; Voßemer & Schuck, 2015), objective (Kracke et al., 2017; Reichelt & Vicari, 2014) or empirical (Boll & Leppin, 2014; Verdugo & Verdugo, 1989) approaches, which differ in how job requirements are identified. Each approach is characterised by significant benefits and drawbacks.Footnote 15Empirical procedures (also referred to as “realised matches”) determine the educational levels within a particular occupation based on the database used. This approach is the least widespread in the empirical literature, which can be attributed to clear problems associated with this approach; that is, the procedure does not reveal the actual requirements of a job and reflects only current allocations and assignments that are influenced by recruitment practices and labour market conditions (Hartog, 2000).

Objective procedures are based on occupations and corresponding educational requirements, which are evaluated by experts. These methods have the advantage that the measurement results cannot be influenced and thereby distorted by the respondent; thus, they are considered purely objective measures. However, a significant disadvantage is that changes in the requirements that occur over time are not adequately represented, or they are represented with a long delay. As a result, the job requirements are not always up-to-date. In addition, job requirements are shown only for certain professional groups or, depending on the procedure, highly aggregated professional groups, which fails to consider the possible spread of requirements within a professional field (intra-professional heterogeneity) and may not represent the actual job requirements. Moreover, the objective measurement (in Germany, this measure is currently made possible via the KldB2010) allows only approximate classifications of job requirements (maximum four levels). Compared to the subjective approach, which draws on five requirement levels, the amount of important information is reduced, and the phenomenon of overqualification is most likely underestimated.

Consequently, this paper uses a subjective procedure based on self-assessments by the participants regarding the level of educational requirements for their job. In general, this measurement is still considered more robust and efficient than the other procedures that measure overqualification (Büchel, 2001; Pollmann-Schult, 2006) because it evaluates the job requirements directly related to a person’s occupational activities rather than the aggregate occupational field. Therefore, the circumstances of individuals and up-to-date information are captured.

The subjective procedure used is consistent with the approach developed by Büchel (1998). This approach uses a categorisation scheme in which the level of educational requirements for a job is compared with the person’s acquired formal qualification level. To optimise the reliability of this comparison and to identify inconsistencies, the professional position is also integrated in the categorisation scheme. The shortcomings of the subjective procedure may include conscious or unconscious misjudgements by respondents, which may be problematic in the case of the underlying migrant population as this approach presupposes that individuals know the qualification level required for their job. However, based on the answer categories in the questionnaireFootnote 16 and the translation of the questionnaire into various languages, we assume that this problem is not a fundamental issue in this study. Moreover, by including the occupational status in the categorisation scheme, as mentioned above, possible distortions caused by subjective misjudgements are reduced (Büchel, 2001; Pollmann-Schult, 2006).

The resulting dependent variable has a value of one if a person has a higher qualification level than actually required for the job and zero if a person is adequately qualified. Accordingly, a person with the qualification level of vocational training is overqualified if his or her occupational status is that of an “employee with a simple activity” and if there is no training required for the job; a person is adequately employed if he or she works in a position requiring completion of vocational training.Footnote 17

Independent variables and controls

We are primarily interested in examining whether and how social capital combined with the characteristics of the social network is connected to migrants’ risk of overqualification. Following the theoretical argumentation, our central approximation of social capital is based on the job search process and the channels activated during the search. Using a variable with three categories, we distinguish the use of informal search methods from the use of formal methods alone and the use of a combination of formal and informal methods. Informal channels include friends, neighbours, family members, former colleagues and former employers; formal search strategies include the use of federal employment offices, job centres, private job agencies, private placement and vacancy advertisements (online or in newspapers).

The theoretical construct of homophily is captured by the composition of the social network and the division between migrants and natives.Footnote 18 Homophilous migrant network composition is designed as a dummy variable that has a value of one if the respondents only or mostly have migrants as friends and a value of zero if half to none of their friends are migrants (= heterophilous migrant/native network). Additionally, we include the interaction term between homophilous migrant network composition and job search methods in the analysis. To identify employment niches, we use information regarding how many of the respondents’ colleagues are also migrants; the resulting dummy variable is equal to one if all or most of their colleagues are migrants and zero otherwise.

To control for additional determinants, further human capital variables are included in the empirical analyses. The database provides detailed information concerning the recognition of international qualifications in Germany. In the empirical models, we can control for migrants’ foreign educational attainment as follows: Their education is recognised as equivalent to the respective German education, their education is partially recognised, or the recognition is pending. As stated above, individuals with unrecognised credentials are excluded from the analyses. To assess German language proficiency, we include an ordinal variable ranging from “very good” to “not at all” based on speaking skills in our analysis. Furthermore, the models account for the country of originFootnote 19 and the reasons for migration. The time spent in Germany since migration is also included in the empirical analysis to control for differences in established social networks or gained knowledge related to labour market issues. Additionally, we control for several individual characteristics including gender, birth cohort and individual labour market experience abroad and in Germany (adjusted for career breaks; all continuous variables are centred on their sample mean). The individual family situation is controlled by variables that capture marital status, cohabitation and the presence of children younger than 16 years of age. The educational achievement of migrants’ parents is also included to control for the social background of the migrants, which also influences the risk that an individual will be overqualified (Erdsiek, 2016; Kracke, 2016). Furthermore, the analysis considers regional characteristics including urban versus rural areas and the location of the federal state (East or West Germany) since the proportion of overqualified employees varies between federal states (Reichelt & Vicari, 2014). In addition, operational characteristics, such as the economic sector and company size, are controlled to avoid operation-specific heterogeneity. However, all these variables serve only as controls to reduce unobserved heterogeneity and are not further interpreted.Footnote 20

In Table 1, the distribution of overqualification and adequate employment is given in total and divided by the explanatory variables. Approximately 54% of the migrants are overqualified. Those who used only informal job search channels are generally more often overqualified than those who used only formal job searches or a combination of informal and formal job searches. Adequately employed migrants have mostly heterophilous migrant/native networks, with a share of approximately 73%. Approximately, 36% of overqualified and 21% of adequately employed migrants work in companies that employ mostly foreign labour. These figures and distributions give a first impression of the prevalence of overqualification among migrants in Germany as well as their job search behaviour and social contacts (private and work related). Based on these values and even without considering third variables, the picture assumed as part of the hypotheses can already be seen: Overqualification accompanies informal job searches rather than formal job searches, with homogenous migrant networks (48% versus 27%) and with mostly foreigners in a company (36% versus 21%). However, do these results hold when analysing multivariate models and controlling for human capital factors and socio-demographic characteristics?

Results

To determine whether social capital is connected to the phenomenon of overqualified employed migrants, we assumed that the probability varies depending on the job search strategies used. Table 2 reports the results of the logistic regressions in which the risk of overqualification in the current occupation is regressed on the corresponding different job search strategies. Model 1 shows that compared to using formal strategies, using only informal job search methods significantly increases the risk of overqualification by 12 percentage points. Using formal and informal strategies simultaneously has no significant effect on the risk of overqualification. Therefore, the use of informal channels alone to obtain information or receive assistance during the job search process is associated with overqualification compared to the use of formal channels or a combination of the two strategies. Thus, for migrants, social contacts are not helpful in finding an adequate job. This result leads to the first conclusion: The resources that migrants gain from their social network during the job search process are not helpful in finding jobs that are adequate to their educational level.

Regarding the mechanisms of homophily, Model 2 additionally includes the ethnic homogeneity of migrants’ networks. The results show that having homophilous migrant networks significantly increases the risk of overqualification by 14 percentage points. The effect of using informal search strategies remains largely stable and significant. These results are consistent with the first hypothesis (H1a) and indicate that having a homophilous migrant network leads to a higher risk of overqualification, regardless of whether the social network has been used during the job search. This result primarily reflects the importance of social networks and the resources they can provide. Having homophilous migrant networks reduces migrants’ access to host-country-related social capital and, thus, general knowledge about the labour market and job application procedures or strategies (Haug, 2003; Kalter, 2006), as this knowledge is highly country specific. However, this knowledge is important or even crucial for finding employment that is adequate to individuals’ educational level. This finding supports the conclusion of Kalfa and Piracha (2015); that is, living in regions with high ethnic concentrations increases migrants’ risk of overqualification.

To account for the relationship between occupational segregation respective employment niches and migrants’ overqualification, the proportion of foreigners in the company is included in Model 3. This model reveals a statistically significant effect. If all or most co-workers are also migrants, the risk of being overqualified increases by 17 percentage points. This result is consistent with our assumption that a relationship exists between the composition of the work environment and the risk that an individual is overqualified in his or her employment (H2). This finding does not reveal a relationship between cause and effect; however, it does reveal a strong relationship between the two. We can conclude from this finding that labour market segments with high concentrations of migrants represent an adverse environment, one that attracts not only individuals with educational levels that are commensurate with the existing job requirements of the environment but also migrants who have higher levels of education than required. Such environments are a significant risk factor regarding migrants’ overqualification.

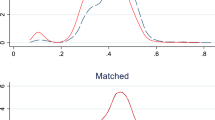

To test whether migrants with homophilous migrant networks are at a greater risk of overqualification if they use informal job search strategies (H1b), we examine the interaction between network homophily and job search strategies. Fig. 1 shows the predicted probability of being overqualified. Migrants with homophilous networks who use only informal search strategies are at the greatest risk of overqualification. Migrants who have heterophilous migrant/native networks and use formal and informal strategies are at the lowest risk of overqualification. Overall, the most important significantFootnote 21 difference among these subgroups is found between migrants with homophilous networks and migrants with heterophilous migrant/native networks who searched only via informal search channels. Additionally, the general interaction term between informal job searches and homophily is significant.Footnote 22 Thus, we conclude that migrants who use informal channels alone to search for jobs are further disadvantaged if they have a homophilous migrant network. This result means that using informal job search strategies such as asking friends or acquaintances and having a heterophilous migrant/native network that provides host-country-specific social capital will lead to a significantly reduced risk of overqualification compared to those with homophilous migrant networks. Thus, the social resources used for searching for a new job are less effective unless migrants have ties to individuals with host-country social capital. As a result, ties to natives help migrants gain access to job opportunities and obtain knowledge regarding how to obtain adequate jobs. We conclude that a combination of informal ways of searching for a job and homophilous migrant networks is apparently a high-risk factor for being overqualified in the labour market.

Robustness checks and limitations

We conducted several additional analyses to ensure that our results are robust. Therefore, we recalculated the analyses by using an objective approach to measure overqualification. We used the 5th digit of the German Classification of Occupations 2010 (in short: KldB 2010), which includes the attribute “requirement level of occupations” for the objective measurement (Kracke et al., 2017). This procedure offers a measurement of educational mismatch based on objective data and criteria but reduces the information because we can only use four categories of required qualifications. However, our conclusions were not substantially changed. As another robustness check, we recalculated our multivariate models in the excluded group of second-generation migrants (born and educated in Germany). As the results do not differ from those found in the first-generation migrants, we conclude that this sample restriction is necessary and does not distort our results. Additionally, we recalculated the analyses only in a subgroup of migrants who wish to permanently remain in Germany. This intention might influence their goals concerning adequate integration in the labour market and thereby finding jobs commensurate with their acquired educational level. However, the results do not substantially differ. To ensure robustness regarding the impact of the job search process and migrants’ networks on the probability of overqualification, we conducted several checks. In particular, we excluded potential selectivity between those persons with the use of social networks and those without and the fact that persons can use networks only if they have them (Mouw, 2003, 2006), and we examined the potential group differences. However, there were no significant differences by socio-demographic characteristics such as age and gender.

Nevertheless, some aspects of the research design must be addressed. Because the dataset provides only two waves (and, therefore, we cannot apply panel estimators), we are unable to draw conclusions regarding intra-individual changes over time or causality. The decision to rely on social resources during the job search is a selective process, and informal job searches might be a function of unobserved heterogeneity on the part of those who resort to such searches. Therefore, we extensively controlled for selective processes i.e. residence permits and homophily, to obtain relatively accurate results; however, causal analytical estimation procedures are preferable. Furthermore, the concepts of overqualification and, thus, educational mismatch cannot account for the (mis)match between required and acquired skills while concentrating solely on the correspondence between occupations and educational levels. This problem is particularly glaring in the case of migrants since educational systems, the skills acquired within such systems and the skill requirements of jobs differ across countries. The relative adequacy of educational credentials acquired abroad for the requirements of jobs in Germany i.e. a country known for tight education-to-work transitions and strong occupational segmentation, may be subject to bias. Additionally, because a discussion of whether migrants know the type of training that is usually required to perform their job is worthwhile, future research should focus on skills mismatch when analysing migrants’ integration into the labour market. Finally, it should be mentioned that a larger number of cases would be desirable for further analyses to ensure that the reliability of the derived conclusions is increased.

Summary and conclusion

In this study, we analyse whether social capital plays a decisive role in migrants’ risk of overqualification in Germany. Overqualification i.e. when the actual qualification level exceeds the job requirements, implies that the human capital acquired through education cannot be converted into appropriate (monetary or non-monetary) returns. In general, empirical evidence regarding the relationship between social capital and overqualification is scarce and mixed (Franzen & Hangartner, 2005; Weiss & Klein, 2011). To date, however, the job search process, and, thus, the direct influence of migrants’ networks on the adequacy of their jobs, has not been considered for Germany. Accordingly, we analyse how — controlling for human capital factors and socio-economic characteristics — migrants’ social networks activated during their job searches relate to the educational adequacy of their jobs.

In general, it can be assumed that activating informal channels (such as friends or family members) during the job search process should have positive effects (Lin et al., 1981) since important job-relevant information can be provided. However, based on theoretical considerations from the social resources approach combined with the mechanism of homophily, we assume that social networks consisting of homophilous others have a negative impact on the risk of being overqualified employed in the case of migrants. Using data from the German IAB-SOEP Migration Sample, first, we find that job searches carried out solely via informal channels are a risk factor for overqualification compared to the use of formal job search strategies. This evidence clearly shows that migrants’ risk of overqualification increases if they use only informal contacts, such as friends, neighbours or former colleagues, while searching for a new job. Second, we find that having homophilous migrant networks (i.e. networks consisting mainly of other migrants) similarly increases the risk of overqualification. Additionally, we find a significant interaction between informal job searches and homophilous migrant networks. This result indicates that a combination of informal ways of searching for a job and homophilous migrant networks is a high risk factor for being overqualified. We conclude that the social resources that can be utilised by migrants in homophilous migrant networks are not beneficial for finding jobs that are adequate to their educational level, especially if they use only informal strategies during their job search. These findings are even more relevant considering that previous studies show that some migrant groups are inclined to rely on informal search strategies (Drever & Hoffmeister, 2008; Seibel & van Tubergen, 2013). Migrants’ lack of host-country-specific social capital, such as important information regarding the functioning of the labour market and job application procedures and strategies, reduces their opportunity to find adequate employment and, consequently, to utilise the entirety of the human capital that they have acquired.

Finally, we show that there is a positive relationship between overqualification and the concentration of co-workers who are also foreigners, which is a particular characteristic of employment niches. This finding implies that such niches exist because migrants are urged into them by individual or structural circumstances rather than because migrants are better suited for those jobs (Constant & Massey, 2005; Simón et al., 2008; Waldinger, 1994). From the individual perspective, it can be helpful to join e.g. co-ethnic family businesses or other jobs in segregated areas of the labour market to enter the labour market or to (first) avoid unemployment. From a structural view, the processes occurring in the labour market can be understood as noteworthy mechanisms that foster and strengthen ethnic segregation. The German labour market is known for being rigid and decidedly focused on credentials. Access to most occupations is highly regulated. Therefore, for migrants, it is essential that foreign credentials be recognised by official bodies. Studies show that such recognition results in jobs for which people are better qualified and a higher occupational status (Kogan, 2016) whereas “[…] the extent to which applicants benefit from foreign credential recognition varies with their occupational experience but not with the quality of the educational system in which they were trained” (Damelang et al., 2020, p. 1). Additional research on the effects of labour market characteristics, especially its segregation and employment niches, and recognition procedures on migrants’ risk of overqualified employment, as well as a theoretical discussion that includes segmentation theory (Sengenberger, 1987) and arguments on occupational closure (Weeden, 2002), would be valuable directions for further research. Therefore, the focus here should be on country-comparative observations that highlight the specificity of the German context and contrast with other countries and systems. Furthermore, for further analysis, panel estimators are crucial to control for job changes and, in turn, for changes from overqualified to adequate employment (and vice versa), to capture changes in educational attainment and to reveal the different effects of changes in migrants’ social networks. Similarly, pursuing further research with retrospective information about pre- and post-migration educational status and career paths could be fruitful. Doing so is necessary to determine whether labour market mismatches are traps or stepping stones into the labour market and adequate jobs in the future; the extent of path dependencies could also be examined in this way. In addition, when focusing on whether migrants’ overqualification is a trade-off in preference of a homogeneous working environment, organisational characteristics should be considered in more detail such as less aggregated levels of economic sectors. Finally, we suggest that future research considers more specific characteristics of migrants’ networks. For example, the educational attainment and employment status of migrants’ social contacts should be considered to gain deeper insights into potential network resources. Another important research approach would be to examine the existing gender differences in this context and in general for the labour market success of migrants.

We contribute to the discussion regarding migrants’ risk of overqualification by showing that — in addition to human capital and socio-economic characteristics — social capital influences migrants’ risk of overqualification in Germany. We link job search methods to migrants’ social environments and show that migrants’ reliance on social contacts during the job search process in combination with the lack of host-country-specific social capital influences the transferability of human capital across national borders and, thus, labour market success in terms of overqualification.

Several policy implications emerge from the present study. For example, relevant institutions, such as federal employment offices or job centres, may need to make formal job search strategies more attractive or even more accessible for all groups of immigrants. Notably, a central factor is the German language, which is a basic requirement for extensive access to host-country specific social capital and the German labour market. All migrants should be able to attend language courses. Interethnic contacts, especially with natives, provide knowledge regarding application procedures and vacancies, and, thus, they support the job search process (additionally, they have a positive influence on employment status and wages (Lancee, 2012)). Such interaction should be facilitated by public authorities and cultural associations. Finally, funding for the adaptation of the qualifications of migrants whose qualifications have only been partially recognised could make an important contribution.

Notes

This paper focuses on overqualification; consequently, it adopts a vertical and educational perspective on labour market (mis)match. Skills mismatch and horizontal adequacy, such as field of study, are not analysed.

As an essential precondition for the transferability of human capital, human capital acquired abroad, in the form of certificates and credentials, must be recognised by the official bodies of the host country (Chiswick & Miller, 2009).

Following Montgomery (1992), Mouw (2003) and Krug (2012), we consider the job search process instead of how the job has been found. Focusing on job finding methods results in misleading outcomes concerning the efficacy of the methods, especially when individuals have used different job search methods.

As a country of immigration, Germany is characterised by two major migratory waves. The first occurred between the mid-1950s and 1973, when Germany had a lack of qualified workers, leading to the recruitment of workers from other countries (e.g. Italy, Turkey), so-called guest-workers. These guest-workers arrived from economically weak areas, had little education and were mainly employed in occupations with low levels of educational requirements. The second wave after 1990 was characterised by immigrants from Eastern Europe, Africa and the Middle East, who had higher levels of human capital than the typical guest-workers during the first wave (Kogan, 2011; Seifert, 2012). For a comprehensive overview of the policy framework for asylum and migration in Germany, please see Schneider (2012).

To date, not all of these theories have been empirically tested for their explanatory power regarding the occurrence of the phenomenon of overqualification. Some can be confirmed for certain countries. For instance, the structural view of the job competition model was verified for the German labour market Büchel (1998); others, however, have no explanatory power or they do only in theoretical extensions.

Following McPherson et al. (2001), we define homophily as inbreeding homophily, indicating that compared to the rate expected in the general population, a higher rate of ties exists within a demographic group.

This study uses factual anonymous data from waves 1 and 2 of the German IAB-SOEP Migration Sample Survey. Data access was provided via a scientific use file supplied by the Research Data Centre (FDZ) of the German Federal Employment Agency (BA) at the Institute for Employment Research (IAB). DOI: 10.5684/soep.iab-soep-mig.2017. The response rate of approximately 32% is in accordance with response rates of earlier SOEP samples (Kroh et al., 2015).

The German IAB-SOEP Migration Sample relies on two data sources that are already available in Germany: the most comprehensive household survey in Germany i.e. the longitudinal study “Living in Germany” conducted by the Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP), and IEB register data, which contain a wide range of labour market variables collected on a daily basis.

For more details regarding the sampling and data documentation, please see the comprehensive survey paper by Brücker et al. (2014).

Considering that vocational education in Germany is highly specialised compared to that in many other countries, the relevant survey question is adapted to capture different types of vocational training. Accordingly, it is ensured that relevant vocational qualifications are not lost. Please see the corresponding question in the Appendix.

As the two waves do not contain the same set of variables, we are unable to adopt a panel design.

The opposite case i.e. that of a person who has a lower level of qualification than required, is called underqualification. Since this phenomenon has completely different determinants, implications and consequences, it is not a part of this particular study.

Please see the Appendix for the survey questions.

The precise questioning and operationalisation steps are included in the Appendix. Overall, we lose 70 cases in this step as these cases cannot be explicitly classified as overqualified or adequately employed.

For reasons of case numbers, we are unable to differentiate between ethnic affiliations.

We have considered different categorisations: we distinguished among EU13 countries, EU15 countries, Southeast Europe, Arabic-speaking countries, former CIS states and the rest of the world; and we distinguished between prosperous countries and impoverished/developing countries. The latter is reported in Table 5; the main effects are unaffected by the different operationalisations.

Summary statistics, including the averages and percentages of all variables, are presented in Table 4 in the Appendix.

Significant at the 10% level.

Significant at the 10% level. The exact results of the interaction effect are shown in Table 6 in the Appendix.

References

Aguilera, M. B. (2002). The impact of social capital on labor force participation: evidence from the 2000 social capital benchmark survey. Social Science Quarterly, 83(3), 853–874.

Aguilera, M. B., & Massey, D. S. (2003). Social capital and the wages of Mexican mi-grants: New hypotheses and tests. Social Forces, 82(2), 671–701.

Ahmad, A. (2015). “Since many of my friends were working in the restaurant”: The dual role of immigrants’ social networks in occupational attainment in the Finnish labour market. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 16(4), 965–985.

Ai, C., & Norton, E. C. (2003). Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Economics Letters, 80(1), 123–129.

Aldashev, A., Gernandt, J., & Thomsen, S. L. (2012). The immigrant-native wage gap in Germany. Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik, 232(5), 490–517.

Battu, H., & Sloane, P. J. (2004). Over-education and ethnic minorities in Britain. The Manchester School, 72(4), 535–559.

Becker, G. S. (1962). Human capital. A theoretical analysis. The Journal of Political Economy, 70(5), 9–49.

Best, H., & Wolf, C. (2010). Logistische regression. In C. Wolf & H. Best (Eds.), Handbuch der Sozialwissenschaftlichen Datenanalyse (pp. 827–854). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Blau, P., & Duncan, O. D. (1967). American Occupational Structure. John Wiley & Sons.

Boll, C., & Leppin, J. S. (2014). Formale Überqualifikation unter ost-und westdeutschen Beschäftigten. Wirtschaftsdienst, 94(1), 50–57.

Borjas, G. J. (1990). Friends or strangers: The impact of immigrants on the US economy. Basic Books.

Brücker, H., Kroh, M., Bartsch, S., Goebel, J., Kühne, S., Liebau, E., et al. (2014). The new IAB-SOEP migration sample: An introduction into the methodology and the contents (SOEP Survey Papers 216).

Büchel, F. (1998). Zuviel gelernt?: Ausbildungsinadäquate Erwerbstätigkeit in Deutschland. Bertelsmann.

Büchel, F. (2001). Overqualification: Reasons, measurement issues, and typological affinity to unemployment. In P. Descy & M. Tessaring (Eds.), Training in Europe.: Second report on vocational training research in Europe 2000 (pp. 528–543). Luxembourg.

Buis, M. L. (2010). Simple interpretation of interactions in non-linear models (Stata Tip 87). STATA Journal, (10), 305–308.

Burt, R. S. (2000). The network structure of social capital. Research in Organizational Behavior, 22, 345–423.

Chiswick, B. R., & Miller, P. W. (2009). The international transferability of immigrants’ human capital. Economics of Education Review, 28(2), 162–169.

Colic-Peisker, V., & Tilbury, F. (2006). Employment niches for recent refugees: Segmented labour market in twenty-first century Australia. Journal of Refugee Studies, 19(2), 203–229.

Constant, A., & Massey, D. S. (2005). Labor market segmentation and the earnings of German guestworkers. Population Research and Policy Review, 24(5), 489–512.

Cornelißen, T., & Sonderhof, K. (2009). Partial effects in probit and logit models with a triple dummy-variable interaction term. STATA Journal, 9, 571–583.

Damelang, A., Ebensperger, S., & Stumpf, F. (2020). Foreign credential recognition and immigrants’ chances of being hired for skilled jobs—Evidence from a survey experiment among employers. Social Forces, Online First, 1–24.

DaVanzo, J. (1981). Repeat migration, information costs, and location-specific capital. Population and Environment, 4(1), 45–73.

de Graaf, N. D., & Flap, H. D. (1988). “With a little help from my friends”: Social resources as an explanation of occupational status and income in West Germany, The Netherlands, and the United States. Social Forces, 67(2), 452–472.

Di Stasio, V., Bol, T., & van de Werfhorst, H. G. (2016). What makes education positional?: Institutions, overeducation and the competition for jobs. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 43, 53–63.

Drever, A. I., & Hoffmeister, O. (2008). Immigrants and social networks in a job-scarce environment: The case of Germany. International Migration Review, 42(2), 425–448.

Erdsiek, D. (2016). Overqualification of graduates: Assessing the role of family background. Journal for Labour Market Research, 49(3), 239–251.

Eurostat. (2011). Migrants in Europe: A statistical portrait of the first and second generation. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Franzen, A., & Hangartner, D. (2005). Soziale Netzwerke und beruflicher Erfolg. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 57(3), 443–465.

Goel, D., & Lang, K. (2009). Social Ties and the Job Search of Recent Immigrants (NBER Working Paper No. 15186). Cambridge, MA.

Granato, N., & Kalter, F. (2001). Die Persistenz ethnischer Ungleichheit auf dem deutschen Arbeitsmarkt. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 53(3), 497–520.

Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360–1380.

Griesshaber, N., & Seibel, V. (2015). Over-education among immigrants in Europe: The value of civic involvement. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41(3), 374–398.

Hartog, J. (2000). Over-education and earnings: Where are we, where should we go? Economics of Education Review, 19(2), 131–147.

Haug, S. (2003). Interethnische Freundschaftsbeziehungen und soziale Integration. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 55(4), 716–736.

Heizmann, B., & Böhnke, P. (2016). Migrant poverty and social capital: The impact of intra- and interethnic contacts. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 46, 73–85.

Ibarra, H. (1992). Homophily and differential returns: Sex differences in network structure and access in an advertising firm. Administrative Science Quarterly, 37(3), 422.

Joona, P. A., Gupta, N. D., & Wademsjö, E. (2014). Overeducation among immigrants in Sweden: Incidence, wage effects and state dependence. IZA Journal of Migration, 3(2014), 1–23.

Jovanovic, B. (1979). Job matching and the theory of turnover. Journal of political economy, 87(5, Part 1), 972–990.

Kalfa, E., & Piracha, M. (2013). Immigrants’ Educational Mismatch and the Penalty of Over-Education (ZA DP No. 7721).

Kalfa, E., & Piracha, M. (2015). Social Networks and the Labour Market Mismatch (Discussion paper series / Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit, Vol. 9493). Bonn: IZA.

Kalter, F. (2006). Auf der Suche nach einer Erklärung für die spezifischen Arbeitsmarktnachteile von Jugendlichen türkischer Herkunft: Zugleich eine Replik auf den Beitrag von Holger Seibert und Heike Solga: ‘Gleiche Chancen dank einer abgeschlossenen Ausbildung?’. Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 35, 144–160.

Kalter, F., & Kogan, I. (2014). Migrant networks and labor market integration of immigrants from the former Soviet Union in Germany. Social Forces, 92(4), 1435–1456.

Klug, C. (2018). Same-sex employees and supervisors: The effect of homophily and group composition on wage differences. Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 47, 240–254.

Kogan, I. (2011). New immigrants — Old disadvantage patterns? Labour market integration of recent immigrants into Germany. International Migration, 49(1), 91–117.

Kogan, I. (2016). Education systems and migrant-specific labour market returns. In A. Hadjar & C. Gross (Eds.), Education System and Inequalities (pp. 279–299). Policy Press.

Korac, M. (2005). The role of bridging social networks in refugee settlement: The case of exile communities from the former Yugoslavia in Italy and the Netherlands. In P. Waxman & V. Colic-Peisker (Eds.), Homeland wanted (pp. 87–107). Nova Science Publishers.

Kossinets, G., & Watts, D. J. (2009). Origins of homophily in an evolving social network. American Journal of Sociology, 115(2), 405–450.

Kracke, N. (2016). Unterwertige Beschäftigung von AkademikerInnen in Deutschland: Die Einflussfaktoren Geschlecht, Migrationsstatus und Bildungsherkunft und deren Wechselwirkungen. Soziale Welt, 67(2), 177–204.

Kracke, N., Reichelt, M., & Vicari, B. (2017). Wage losses due to overqualification: The role of formal degrees and occupational skills. Social Indicators Research, Online First.

Kroh, M., Kühne, S., Goebel, J., & Preu, F. (2015). The 2013 IAB-SOEP migration sample (M1): Sampling design and weighting adjustment. SOEP Survey Papers Series C - Data Documentations. (SOEP Survey Papers 271). Berlin.

Krug, G. (2012). (When) is job-finding via personal contacts a meaningful concept for social network analysis?: * A comment to Chua (2011). Social Networks, 35, 527–533.

Lancee, B. (2012). The economic returns of bonding and bridging social capital for immigrant men in Germany. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 35(4), 664–683.

Leschke, J., & Weiss, S. (2020). With a little help from my friends: Social-network job search and overqualification among recent intra-EU migrants moving from east to west. Work, Employment and Society, 34(5), 769–788.

Lin, N. (2000). Inequality in social capital. Contemporary Sociology, 29, 785–795.

Lin, N., Ensel, W. M., & Vaughn, J. C. (1981). Social resources and strength of ties: Structural factors in occupational status attainment. American Sociological Review, 46(4), 393.

Maynard, D. C., Joseph, T. A., & Maynard, A. M. (2006). Underemployment, job attitudes, and turnover intentions. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 27(4), 509–536.

McGuinness, S. (2006). Overeducation in the labour market. Journal of Economic Surveys, 20(3), 387–418.

McGuinness, S., & Byrne, D. (2015). Born abroad and educated here: Examining the impacts of education and skill mismatch among immigrant graduates in Europe. IZA Journal of Migration, 4(1), 17.

McGuinness, S., & Sloane, P. J. (2011). Labour market mismatch among UK graduates: An analysis using REFLEX data. Economics of Education Review, 30(1), 130–145.

McKee-Ryan, F. M., & Harvey, J. (2011). “I have a job, but…”: A review of underemployment. Journal of Management. Journal of Management, 37(4), 962–996.

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 415–444.

Montgomery, J. D. (1992). Job search and network composition: Implications of the strength-of-weak-ties hypothesis. American Sociological Review, 57(5), 586–596.

Mouw, T. (2003). Social capital and finding a job: Do contacts matter? American Sociological Review, 68(6), 868.

Mouw, T. (2006). Estimating the causal effect of social capital: A review of recent research. Annual Review of Sociology, 32(1), 79–102.

Moya, J. C. (2007). Domestic service in a global perspective: Gender, migration, and ethnic niches. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 33(4), 559–579.

Nielsen, C. P. (2011). Immigrant over-education: Evidence from Denmark. Journal of Population Economics, 24(2), 499–520.

Piracha, M., & Vadean, F. (2013). Migrant educational mismatch and the labour market. In A. Constant & K. F. Zimmermann (Eds.), International handbook on the economics of migration (pp. 176–192). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Piracha, M., Tani, M., & Vadean, F. (2012). Immigrant over- and under-education: The role of home country labour market experience. IZA Journal of Migration, 1(2012), 1–21.

Pollmann-Schult, M. (2006). Unterwertige Beschäftigung im Berufsverlauf: Eine Längsschnittuntersuchung für Nicht-Akademiker in Westdeutschland. Zugl.: Berlin, Freie Univ., Diss., 2003 (Europäische Hochschulschriften Reihe 22, Soziologie, Vol. 410). Frankfurt am Main u. a.: Lang.

Pollmann-Schult, M., & Büchel, F. (2002). Ausbildungsinadäquate Erwerbstätigkeit: eine berufliche Sackgasse?: Eine Analyse für jüngere Nicht-Akademiker in Westdeutschland. Mitteilungen aus der Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung, 35(3), 371–384.

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone. The collapse and revival of American Community. Simon and Schuster.

Rafferty, A. (2012). Ethnic penalties in graduate level over-education, unemployment and wages: Evidence from Britain. Work, Employment and Society, 26(6), 987–1006.

Reichelt, M., & Vicari, B. (2014). Ausbildungsinadäquate Beschäftigung in Deutschland: Im Osten sind vor allem Ältere für ihre Tätigkeit formal überqualifiziert. IAB-Kurzbericht, (25), 1–8.

Romiti, A., Trübswetter, P., & Vallizadeh, E. (2015). Lohnanpassungen von Migranten: Das Soziale Umfeld gibt die Richtung vor. IAB-Kurzbericht, 25.

Schneider, J. (2012). The organisation of asylum and migration policies in Germany: Study of the German National ContactPoint for the European Migration Network (EMN) ((Working Paper / Bundesamt für Migration undFlüchtlinge (BAMF) Forschungszentrum Migration, Integration und Asyl (FZ) 25). Nürnberg.

Seibel, V., & van Tubergen, F. (2013). Job-search methods among non-western immigrants in the Netherlands. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 11(3), 241–258.

Seibert, H. (2011). Berufserfolg von Jungen Erwachsenen mit Migrationshintergrund. Wie Ausbildungsabschlüsse, ethnische Herkunft und ein Deutscher Pass die Arbeitsmarktchancen beeinflussen. In R. Becker (Ed.), Integration durch Bildung: Bildungserwerb von Jungen Migranten in Deutschland (pp. 197-226). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Seifert, W. (2012). Geschichte der Zuwanderung nach Deutschland nach 1950. http://www.bpb.de/politik/grundfragen/deutsche-verhaeltnisse-eine-sozialkunde/138012/geschichte-der-zuwanderung-nach-deutschland-nach-1950?p=all.

Sengenberger, W. (1987). Struktur und Funktionsweise von Arbeitsmärkten: die Bundesrepublik Deutschland im internationalen Vergleich. Frankfurt am Main: Campus.

Simón, H., Sanromá, E., & Ramos, R. (2008). Labour segregation and immigrant and native-born wage distributions in Spain: An analysis using matched employer–employee data. Spanish Economic Review, 10(2), 135–168.

Spence, M. (1973). Job market signaling. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(3), 355–374.

Thomsen, S. (2010). Mehr als “weak ties” – Zur Entstehung und Bedeutung von sozialem Kapital bei hochqualifizierten BildungsausländerInnen. In A.-M. Nohl, K. Schittenhelm, O. Schmidtke, & A. Weiß (Eds.), Kulturelles Kapital in der Migration: Hochqualifizierte Einwanderer und Einwandererinnen auf dem Arbeitsmarkt (1st ed., pp. 260–271). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Thurow, L. C. (1975). Generating inequality: Mechanisms of distribution in the U.S. economy. Basic Books.

Verdugo, R. R., & Verdugo, N. T. (1989). The impact of surplus schooling on earnings: Some additional findings. Journal of Human Resources, 24(4), 629–643.

Verhaest, D., & Omey, E. (2006). The Impact of Overeducation and its Measurement. Social Indicators Research, 77(3), 419–448.

Verhaest, D., & Omey, E. (2010). The determinants of overeducation: Different measures, different outcomes? International Journal of Manpower, 31(6), 608–625.

Voßemer, J., & Schuck, B. (2015). Better overeducated than unemployed? The short-and long-term effects of an overeducated labour market re-entry. European Sociological Review, 32(2), 251–265.

Waldinger, R. (1994). The making of an immigrant niche. International Migration Review, 28(1), 3–30.

Weeden, K. A. (2002). Why do some occupations pay more than others? Social closure and earnings inequality in the United States. American Journal of Sociology, 108(1), 55–101.

Weiss, F., & Klein, M. (2011). Soziale Netzwerke und Jobfindung von Hochschulabsolventen – Die Bedeutung des Netzwerktyps für monetäre Arbeitsmarkterträge und Ausbildungsadäquatheit. Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 40(3), 228–245.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

-

1.

Questionnaire “highest qualification level”

What kind of education or training was it?

-

I received in-house training at a company

-

I completed an extended apprenticeship at a company

-

I attended a vocational school

-

I attended a university/college with a more practical orientation

-

I attended a university/college with a more theoretical orientation

-

I completed doctoral studies

-

Other

-

2.

Questionnaire “educational requirements”

What kind of training is usually required for doing this job?

-

No training required

-

Semi-skilled training required

-

Completed vocational training required

-

Completed university education (university or university of applied sciences) required/doctorate/habilitation required

-

3.

Questionnaire “job search”

Think back to when you were looking for your current job. Which of the following methods and services did you use to find this job?

-

Employment office (Agentur für Arbeit)

-

Job-Center/ARGE/social services

-

Personnel service agency

-

Private recruitment agency

-

Job advertisement in the newspaper

-

Job advertisement on the Internet

-

Former co-workers

-

Friends, acquaintances, and neighbours

-

Family members

-

Returned to a previous employer

-

Other/does not apply

-

4.

Questionnaire “homophilous networks”

What is your circle of friends like:

How many of your friends are not from Germany or have parents who are not from Germany?

-

All

-

Most

-

About half

-

About a quarter

-

Less than a quarter

-

None

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kracke, N., Klug, C. Social Capital and Its Effect on Labour Market (Mis)match: Migrants’ Overqualification in Germany. Int. Migration & Integration 22, 1573–1598 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-021-00817-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-021-00817-1