Abstract

In this paper, we use original linked data to better understand the relationship between remigration intentions and actual behaviors and, more specifically, to verify whether remigration intentions can predict migrants’ actual behaviors. To do so, we compare self-declared remigration intentions with actual departures during the 2 years following a survey. Then, we analyze to what extent the factors associated with both dimensions are similar. The results show that 96% of migrants who wanted to stay in Switzerland actually stayed and that 71% of those who wanted to leave the country actually left. Overall, intentions were a good predictor of behaviors, and the factors associated with remigration intentions and actual behaviors were almost the same. However, intentions reflected migrants’ personal feelings at the time of the survey and sometimes reflected their potential to remain in Switzerland from a legal point of view. Behaviors were more rational than intentions in that migrants’ reflections on their actual situations were more profound, and their choices to stay in Switzerland or to leave were thus influenced by rational elements such as their labor market situations or family constraints.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Migrant workers are currently very important for the economies of industrialized countries. In Switzerland, recently arrived migrants (those arriving in the last 10 years) represent approximately 17% of the working-age population.Footnote 1 Migration to Switzerland takes place in the context of the bilateral Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons (AFMP), which authorizes citizens of the European Union and Switzerland to freely choose their place of residence within the EU/EFTA territory. For non-EU/EFTA nationals arriving in Switzerland, who represent 40% of migrants (D’Amato et al. 2019), migration is partially managed by different quota systems, with the aim of providing the necessary work force for the Swiss economy. The share of asylum seekers and refugees among the Swiss foreign population was of 5.6% at the end of the year 2018 (SEM 2020), indicating that most of the migrants came to Switzerland for professional or family-related reasons. Migrant workers play an important role in specific economic sectors, such as health and care, restoration, construction, and managerial activities. Thus, it is important for both economic actors and policy makers to understand migrants’ mobility behaviors and particularly the durations of their stays and their possible settlement or return/onward migration.

The labor market is increasingly open and internationalized, which can promote competition between countries or regions in attracting highly skilled workers. In the context of increasing mobility in Europe and the specialization of national and regional economies, a better understanding of the international mobility of workers is necessary to plan future needs for foreign workers. Therefore, understanding remigration behaviors is also necessary to implement specific measures to prevent the overly rapid departure of foreign workers, which can result in costly worker turnover, increased recruitment costs for enterprises, or even labor force shortages, specifically in some economic sectors where migrants are well represented. As mentioned by Constant and Massey (2002), “whether emigrants are positively or negatively selected, their departure has important implications for a nation’s population, society and economy”.

Switzerland is an interesting country in which to study migration flows, as it is characterized by a high level of arrivals and departures and positive net migration since the mid-1990s. Every year, Switzerland has more than 100,000 departures among its population of 8 million. In 2017, Switzerland had approximately 15 emigrations per 1000 inhabitants, a rate higher than that of other Western European countries of similar sizes, such as Austria (7.5 per 1000), Belgium (7.5 per 1000), and the Netherlands (6.3 per 1000Footnote 2). According to the Swiss Mobility Migration Survey (Steiner and Wanner 2019), immigration to Switzerland is mainly motivated by professional reasons. Because of the importance of labor force migration, in 2017, 82% of emigrants were aged from 20 to 64 at the time of their emigration, thereby impacting the labor market.

The relative weakness of the theoretical approach to explaining remigration behaviors is surprising given the increasing importance of temporary migration; this weakness is linked to the lack of empirical data on emigration flows and, in particular, on the reasons for return/onward migration. New data are necessary to better understand the behaviors of migrant workers regarding their settlement or remigration and, more generally, to link remigration intentions with actual behaviors.

The factors behind a migrant’s choice to return to his or her country, to migrate to a third country, or to settle have been poorly documented for a long time (Dustmann 1996; Cassarino 2004). More recently, an increased number of studies have been published on the topic. Theories such as that proposed by Borjas and Bratsberg (1996) suggest that the choice to remigrate rather than settle is determined either by a failure to achieve the objectives that motivated the decision to migrate or by the total achievement of the goals anticipated by migrants who wanted to stay abroad for a limited period of time. However, the situation is far too complex to be explained by a single theory. Constant and Massey (2002) demonstrated that migrants are a very heterogeneous group with respect to their motivations, which makes it difficult to understand which parameters influence their return. Nevertheless, as stated by Constant and Massey (2002), the decision to settle or to migrate is made by the migrant himself or herself, who has accurate information on the living conditions in the host country and in the country of origin (in terms of wages, working conditions, and climate). Thus, the migrant can respond in a rational way when asked about his or her projects. For this reason, information on migrants’ intentions regarding future migration can help us determine trends in remigration as well as better understand the factors behind the decision to leave a country. However, when focusing on migrants’ intentions regarding settlement in or departure from a host country, we are aware that intentions can change rapidly according to migrants’ experience or the events that occur as part of their professional and family life trajectories.

Surveys on emigration intentions generally focus on native residents of countries in the South (see, for instance, the Gallup survey, Migali and Scipioni 2018). The empirical relationship between migration intentions and actual flows has been increasingly investigated during the last decade in the context of developing countries (van Dalen and Henkens 2008; Docquier et al. 2014; Laczko et al. 2017; Carling 2017; Tjaden et al. 2019). The existing literature has generally focused either on the determinants of remigration behavior or on the migrants’ self-declared intentions to leave their own country of origin, but it has not simultaneously addressed both intentions and behaviors. This absence of an examination of the relationship between the two dimensions is due to a lack of adequate data. A recent survey conducted among 5973 migrants in 2016 (Steiner and Wanner 2019) with a follow-up in 2018 filled this gap by providing a comparison of migrants’ self-declared remigration intentions with their situations 2 years after the survey. By extension, this survey provided a better understanding of the factors that influence both intentions and actual behaviors, as well as the factors explaining the mismatch between the two dimensions. The survey was representative of the foreign population who arrived in Switzerland in 2006 and then received a residence permit. This population was rather highly qualified, comprising mostly individuals from EU countries who integrated into the labor market. Asylum seekers and undocumented migrants were not included in the sample.

In this overall context, the aim of this paper is first to compare remigration intentions and behaviors during the 2 years between the 2016 survey and the end of 2018. The second aim is to identify the factors associated with remigration intentions and behaviors among recently arrived migrants and to discuss whether the determinants of both dimensions are the same to understand the extent to which intentions can predict the future behavior of this group.

State of the Art

Theorizing Emigration

Different microeconomic and macroeconomic theories have been applied to understand and explain international migration (see, for instance, Zlotnik 2006; De Haas 2014). However, most of these theories have been focused on immigration and have suggested that migrants’ rationale for moving to a country or a region is to improve their own living conditions or that of their families or households. Few theories have focused specifically on remigration (i.e., return or onward migration), which occurs at the end of the mobility process and after migrants have lived some years in a context that is generally different from that of the country of origin.

Among the theories focusing on remigration, the abovementioned theory of selective migration from Borjas and Bratsberg (1996) is the most frequently cited. Based on the theory of the rationality of migrants and neoclassical migration theory (which views migratory movements as cost-benefit decisions), we distinguish two groups of reasons why migrants leave a country to return to the origin country (or go to a third country). The first group of reasons refers to the achievement of the (professional, educational, etc.) objectives that migrants defined before their departure. Migrants return to their countries once they have achieved their defined objectives (see also de Haas and Fokkema 2011) as long as they have not modified their anticipated objectives. Cerase (1974) also suggested the idea of the “return of innovation,” which is when a migrant decides to use the new skills acquired during his or her experience in the host country to achieve his or her professional goals in the country of origin. Rodriguez and Egea (2006) showed that return plans among Andalusian emigrants living in Northern Europe were linked to their original immigration decision and that return migration occurred according to these original decisions. These results are in line with the new economics of labor migration, in which migration is viewed as temporary, with the main objective being the accumulation of savings before returning home (Stark 1991).

The second group of reasons refers to the failure of migration, sometimes due to erroneous information on the potential gains of migration or a migrant’s overestimation of his or her own capacity to integrate into a new country (OECD 2008). Remigration is thus a result of the migrant’s inability to achieve the objectives of migration in terms of, for instance, quality of life, income, working objectives, or life achievements. Such “mistaken migrants,” as they are called by Constant and Massey (2002), choose to leave the host country rather than to continue to be disillusioned by the migratory experience.

The reasons to leave the host country are thus based on two opposite migration outcomes. Migrants can be positively or negatively selected in terms of labor market performance, as either the realization of economic objectives or a lack of success can lead to remigration. As Borjas and Bratsberg (1996) mentioned, the decision to depart is a rational decision by the migrant. However, sometimes, migration occurs due to the migrant’s inability to access a long-term permit. Migration also takes place in a context in which the migrant has enough knowledge of both the country of origin and the host country to rationally decide to stay or return.

Intentions and Behaviors

Remigration behavior is sometimes influenced by unexpected events, such as the end of the authorization of residence or unexpected family obligations in the country of origin. Therefore, remigration does not always reflect the desire of the migrant but rather might reflect the actual situation. In contrast, migrants’ declared intentions regarding settlement or remigration can provide more accurate information on migrants’ desires regarding their future. The dimension of migrants’ intentions, which can be assessed through surveys, has therefore been increasingly used to better understand migration. In particular, in recent decades, academic researchers have shown a growing interest in studying the actual consequences of intentions to migrate (Migali and Scipioni 2018), i.e., the relationship between declared intentions and actual behaviors. Theories and empirical research have indicated that intentions to migrate internationally (either to leave one’s country of origin or return to it after a stay abroad) affect actual migration behaviors in that concrete opportunities translate a desire into an actual decision to act (Docquier et al. 2014; van Dalen and Henkens 2008; Armitage and Conner 2001; De Jong 2000; Carling and Pettersen 2014; Carling 2014; Creighton 2013). The link between intentions and actual behavior is, however, not linear, as intentions can be affected by different elements regarding actual opportunities to migrate and the available information (De Haas 2014; Snel et al. 2015). Moreover, unanticipated events can occur in the life trajectory between the time when an intention is declared and the possible remigration.

There is no single path from intentions to actual behaviors but rather a multitude of different schemes. Carling (2017) attempted to theorize the process between the so-called root causes of migration (conditions of states and prospects for improvement), the desire for change, migration aspirations, and, finally, migration outcomes. According to this author, the relationship between the desire for change and migration is influenced by the migration infrastructure, which reflects the human and nonhuman elements that enable and shape migration. In some contexts in which emigration is expensive and difficult to organize, such as in Southern countries, the lack of migration infrastructure can increase the gap between intentions and behaviors. In contexts of free movement and increasing mobility, such as in Europe, this gap is probably less important due to the better opportunities to migrate. The same is anticipated in Switzerland: EU citizens benefit from the free movement of persons. Non-Europeans have mostly been admitted because of their professional knowledge or family situation, and their residence is considered stable.

Few studies have compared intentions for future behaviors at an individual level. The difficulty to perform such comparisons is due to the lack of data that allow for the comparison of behavioral intentions from a longitudinal perspective. Among the existing studies, a study conducted in the Netherlands (van Dalen and Henkens 2008) focused on the native population and showed a link between the two dimensions of intentions and behaviors by reporting that approximately one-quarter of the Dutch inhabitants who stated intentions to leave the country emigrated in the following 2 years. A second study by Steinmann (2019) investigated Polish and Turkish immigrants in Germany. The author tested the variables commonly used to explain remigration in relation to immigrants’ intentions to remigrate. In particular, the author observed that “the initial motives for migration, as well as (economic, social, and cultural) ties to receiving and origin countries, contribute to explaining newcomers’ return plans, whereas perception of ethnic boundaries plays a minor role.” Finally, a third study based on data from the German Socio-economic Panel from 1984 to 2009 explored the difference between migration intentions and actual return migration. In this study, van den Berg and Weynandt (2012) observed that migrants tended to underestimate the length of their stays in the receiving country. Among the migrants who intended to return in 1984, more than two-thirds did not leave the country between 1984 and 2009.

Factors Behind the Intention to Re-Emigrate and Remigration

In the literature, the determinants of both intentions to remigrate and remigration have been investigated. Often, these determinants play a role in both dimensions. Some determinants are consistent with the neoclassical theory of migration, highlighting the economic profit of migration, while others are consistent with the new economics of migration, with a focus on transnational ties and family abroad. Other factors are related to specific events in migrants’ life trajectories.

The factors identified in the literature as influencing remigration intentions and behaviors include the age upon entry to the host country (Dustmann 1996), the motive for initial migration (Mak 1997; Steinmann 2019), and the number of years of residence in the host country (Constant and Massey 2003; Dustmann 1996; van Baalen and Müller 2009). With an increasing duration of stay in a country, there is a decrease in the rate of departure, which is explained by the migrant’s integration into the new country of residence.

Remigration also varies according to the stage of the migrant’s life and family trajectories (Coulter et al. 2011; Ette et al. 2016), as well as gender. Generally, men are more concerned with return migration than women, especially among migrants coming from Southern countries and arriving in Western countries. Western countries often offer a better context in terms of gender equity (Bachmeier et al. 2013), which makes women less interested than men in remigration. The presence of the migrant’s family (and in particular the partner or the children) in the host country diminishes intentions to remigrate and the probability of remigration (Pecoraro 2012; Steinmann 2019; van Dalen and Henkens 2013; Harvey 2009; Pungas et al. 2012). A migrant’s family staying in the country of origin not only is generally related to a desire for temporary migration with an anticipated return but also can result in difficulties in family reunification. For both reasons, having family abroad positively influences intentions to return home. The presence of close family abroad can also be temporary before family reunification, which can ultimately result in a longer stay in the host country; thus, it seems important to accurately understand the impact of the place of residence of family members and to have information regarding family reunification expectations and how long family separation will last. In the same way, the presence of transnational ties (expressed, for instance, by the frequency of travel abroad and the link maintained with the country of origin) can generally be considered a factor that increases intentions to re-emigrate (Steinmann 2019; Haug 2008; Cassarino 2004).

Human capital, which is generally represented by variables such as education level and the number of years of work experience, may also influence intentions to remigrate (Cassarino 2004); however, this association is not always observed, as mentioned by Pungas et al. (2012), who studied Estonian migrants in Finland and did not find any association between the level of education and the probability of return migration. Highly skilled migrants are expected to be more mobile than less skilled migrants (Jasso and Rosenzweig 1988; Pecoraro 2012), particularly because they are involved in an international labor market with more professional opportunities abroad and because they have better access to information (Coulter et al. 2011; Sapeha 2017). However, Borjas (1989) and Massey (1987), working with immigrants in the USA, observed a negative selectivity of remigration, meaning that the less educated and less economically successful immigrants were, the more likely they were to emigrate.

The level of social integration not only is generally linked with human resources but also is directly associated with both intentions to leave a country and actual remigration. For instance, this link is demonstrated by the relationship between the presence of a social network in the host country for the migrant and remigration intentions and behaviors (van Dalen and Henkens 2013; de Vroome and Tubergen 2014). However, causality between the social integration and remigration intentions and behaviors has not been well established. Another indicator of integration into the host society, namely, speaking the local language, has also been associated with lower intentions to leave (Steiner and Velling 1992; Ette et al. 2016).

Difficulty or failure in achieving migration objectives can be experienced by those arriving in a country to work as a result of unemployment. This generally leads to an increased risk of remigration (Pecoraro 2012). In contrast, a good professional position and owning a (family) business in the host country decrease this risk (de Haas and Fokkema 2011; Paparusso and Ambrosetti 2017). Based on a survey of Estonians living in Finland, Pungas et al. (2012) showed that intentions to re-emigrate were associated with overeducation (migrants working below their training level), which is an indicator of weak performance in the labor market. However, Pecoraro (2012) observed that the best-performing workers in the Swiss labor market tended to leave Switzerland more frequently than those who performed less well, probably because they could integrate more easily into other labor markets. According to Steiner (2019), the absence of structural integration is frequently considered an important factor in explaining remigration intentions, even though few studies (de Haas et al. 2015; Carling and Pettersen 2014) have observed that sociocultural factors are more important.

According to Waldorf (1995), the intention to return (and probably actual return) is also negatively affected by satisfaction with migration.

Institutional factors, such as the kind of permit (Massey and Akresh 2006; Ette et al. 2016), which is linked to the possibility of settlement, also play a role. In addition, the political situations in both the country of origin and the host country can affect intentions, as they can influence the actual possibility of reimmigration (Carling and Pettersen 2014). For Dustmann and Weiss (2007), return migration is associated not only with economic considerations but also with migrants’ preferences and the difference in the cost of living between the host country and the country of origin. The existence of bilateral agreements that allow mobility is a factor in remigration (intention), as leaving the host country is not a definitive choice and can be reversed.

Among the factors influencing departure, Steinmann (2019) also identified the “immigrant’s perception of ethnic boundaries,” which refers to the perception of a lack of acceptance of migrants among the host population, for instance, due to xenophobic attitudes. Among the Estonian population in Finland, Pungas et al. (2012) observed that those who did not identify themselves as ethnic Estonians had lower intentions to return to their home countries, which, according to the author, “may be explained by either less attachment to Estonia or perceived discrimination in that country”.

Data and Methods

In this paper, we aim to verify whether declared intentions to remigrate are a good predictor of remigration behavior from an individual perspective. To do so, we use original data on intentions to leave Switzerland among a sample of migrants surveyed in 2016 and compare their intentions with their behaviors from 2016 to 2018.

The Migration-Mobility Survey, a biannual survey, was conducted for the first time in 2016 with a sample of 20,136 foreigners (Steiner and Wanner 2019). Among the people in the sample, 5973 responded online or by phone to a large variety of questions referring to their migration trajectories, their economic and social integration in Switzerland, their family life, and their expectations for the future. The sample was drawn by the Swiss Federal Office using the Swiss Population Register. The conditions to be part of the sample were as follows: being foreign born; being aged 18 or older at the time of arrival in Switzerland and 24–64 at the time of the survey; being German, Austrian, French, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, a UK citizen, North American, Latin American, Indian, or West African; and having arrived in Switzerland in 2006 or later. Asylum seekers and refugees were excluded, as were undocumented migrants. The sampling procedure included stratification based on nationality and the duration of residence to oversample recently arrived migrants (those with less than 2 years of residence). The survey was conducted in the six most commonly used languages (English, German, French, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish) among the migrant population. The response rate was slightly higher than expected for a survey among such a mobile population (37.2%).

The choice not to be exhaustive regarding citizenship was made to focus on the main groups of foreigners in Switzerland and to take into account the language barriers that can occur among recently arrived migrants. All the migrants included in the sample were offered the possibility of answering in their national language, with the exception of Indians, as it was assumed that this population would be able to answer in English. Overall, the nationalities included in the survey represent more than two-thirds of the total foreign population. Among the largest groups not represented were migrants coming from the Balkan region, Turkey, and some Eastern European countries.

In Fall 2016, the respondents were invited to answer questions about their intentions to stay in Switzerland:

-

1)

Is your stay in Switzerland limited in time? (yes, no, I do not know yet)

-

2)

How many more years would you like to stay in Switzerland? (number of years, forever, I do not know yet)

-

3)

(For those who indicated a number of years) How often have you considered emigrating from Switzerland in the last 3 months? Was it… very often, often, from time to time, or never?

-

4)

(For those considering emigrating) Do you plan to emigrate within the next 12 months?

A detailed analysis of the answers showed that the respondents were influenced by their legal status and the durations of their current permits when answering the first question. They did not answer in terms of their personal intentions but provided objective information based on the durations of their permits. Therefore, the second question was favored in the analysis, and three groups were considered: those who wanted to stay in Switzerland for 2 years or less, those who wanted to stay in Switzerland for more than 2 years or forever, and those who did not know yet (undecided population).

At the end of 2018, we obtained information from the Swiss Population Register through the Swiss Federal Statistical Office regarding the residential status of each of the 5973 respondents (present or not present in Switzerland).Footnote 3 We were then able to compare the answers the respondents provided in 2016 regarding their intentions to stay or not stay with their current situations.

In the descriptive analysis, we compared the respondents’ reported intentions with their actual status (present in Switzerland or departed). The descriptive results that are presented were weighted to take into account the nonresponse rate. By doing so, we considered the potential nonresponse biases and could assume that the results were representative of the whole population.

In the second part of the analysis, logistic regressions were run to measure the association of different factors identified in the literature with both intentions and actual behaviors (departure). Logistic regressions (Cox and Snell 1989) were intended to explain the probability (p) of skill mismatch according to the dimensions under study and different control variables (Cox and Snell 1989). The formula is as follows:

where β_0 is a constant and β_(1,…n) are the coefficients of the explanatory variables x_(1,… n). The exponential value of β_(1,…n) is the odds ratio.

For all models, the levels of significance (* p < 0.10; ** p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01) are presented to facilitate the interpretation of the results.

Two series of logistic models were built to test the associations between factors and three dependent variables:

-

1)

Intention to leave Switzerland within the next 2 years

-

2)

Actual departure observed from 2016 to 2018

The results obtained were compared to verify whether the factors associated with the dependent variables were the same. Based on the literature review and the survey items, the following factors were introduced into the models:

-

Demographic and family-related factors

-

Gender: male (reference category), female.

-

Conjugal relationship with a spouse/partner (in the same household or elsewhere): yes (reference category), no.

-

Shared household with a spouse/partner or at least one child: no (reference category), yes.

-

Factors associated with the migration trajectory

-

Age upon arrival: 18–24, 25–34 (reference category), 35–44, 45–64.

-

Time since migration: less than 2 years (reference category), 2 years or more.

-

Reason for immigration to Switzerland: professional reasons only (reference category), family reasons only, both family and professional reasons, other reasons.

-

Transnational ties

-

Spouse/partner or at least one child abroad: no (reference category), yes.

-

Visited the country of origin in the last 2 years (or since arrival): no (reference category), yes.

-

Institutional factors

-

Type of permit: B or C (annual or settlement permit – reference category), short-term permit, or other (nonstable) permit.

-

(Self-declared) origin: EU/EFTA countries (reference category), other OECD countries, other non-OECD countries.

-

Professional factors

-

Level of education: secondary I, secondary II (reference category), tertiary.

-

Employment status: actively employed (reference category), unemployed, student, not active.

-

Arrival due to a professional transfer in the same enterprise: yes, no (reference category).

-

Perceived improvement in professional position: improved significantly, improved slightly, remained the same (reference category), worsened slightly or significantly.

-

Social integration

-

Interest in news and local events in Switzerland: on a linear scale from 0 (no interest) to 7 (very interested).

-

Language skills (based on self-declared ability to speak the local language): good/excellent (reference category), poor.

-

Satisfaction regarding migration: on a linear scale from 0 (very satisfied) to 10 (not at all satisfied).

-

Perceptions of acceptance

-

Self-perception of discrimination: no (reference category), yes.

In light of the factors identified in the literature, two characteristics of our models should be mentioned. First, institutional factors were represented by the permit type, which provided a proxy for legal authorization to stay in Switzerland,Footnote 4 and the place of origin, which provided an indication of the differences in the living conditions between Switzerland and the country of origin.

To better understand the capacity of the different factors to explain migration intentions and behaviors, two logistic regressions were performed for each dependent variable. Model 1 included demographic and family-related factors and migration-related factors (trajectory, institutional factors, and transnational ties). Model 2 also included professional factors. Thus, the differences observed between the two models (for instance, an improvement in the prediction capacity as indicated by Somers’s D) were due to the impact of professional factors on the dependent variables. Model 3 additionally included factors related to living conditions (social integration and perceptions of acceptance).

Results

Descriptive Results

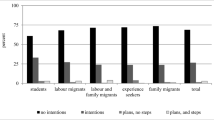

As previously mentioned, 5973 migrants were surveyed, and 5961 of them provided information on their intentions. Table 1 shows the distribution of the migrants according to their intentions and behaviors and the characteristics under study. Table 1 presents the sample size (number of respondents) and the weighted proportions, as well as the distribution of the sample according to the different characteristics. Overall, less than 3% of the respondents intended to stay less than 2 years in Switzerland; this proportion ranged between 1.2 (migrants who came to Switzerland for both professional and family reasons) and 8.8% (migrants who had short-term permits). The proportion of respondents who remigrated was more than four times higher, at 12.6%. This proportion ranged from 7.4 (again, migrants who came for both professional and family reasons) to 36.2% (migrants who held short-term permits).

Table 2 compares intentions with behaviors. Among those respondents who declared that their stays were not limited in time, less than 5% left Switzerland during the 2 years following the 2016 survey, as 95% were still in the country. Among those who said that their stays were limited, more than one-third (35%) left Switzerland. The proportion of those who did not know who left the country was in between the other two proportions, with 12% of these respondents having left Switzerland. Therefore, among the respondents, departure could be anticipated somewhat well based on their intentions, which can be partially explained by the formulation of the question, which referred not only to the respondents’ intentions but also to their legal ability to stay, as mentioned previously.

Regarding the second question on intentions, among the respondents who declared their intentions to stay in Switzerland forever, 3% left Switzerland during the 2-year period. Among the few respondents who intended to stay less than 2 years in Switzerland, more than 80% left. Thus, the respondents’ intentions were confirmed to accurately predict their future behaviors. The same conclusion can also be drawn for the third and fourth questions about having thought about emigrating in the last 3 months and planning to emigrate in the next 12 months (Table 2). The results confirm that the questions about intentions could predict, to some extent, actual remigration behaviors. All the results were significant according to the chi-squared test; thus, the hypothesis of the independence of intentions and behaviors was rejected.

Table 3 summarizes the results based on the answers to question H2 by combining the responses of those who wanted to leave in the next 24 months (wanted to leave) and those who wanted to stay 2 years or more (wanted to stay). It was thus possible to compare intentions with actual behaviors. The so-called success ratio was computed by taking into account the proportion of respondents whose behaviors met their expectations (for instance, those who left Switzerland after declaring their intentions to leave the country within the next 2 years). The success ratio was 72% for those who wanted to leave (as 28% did not achieve their objectives or changed their minds) and 96% for those who wanted to stay (as 4% decided to leave). Moreover, among those who did not know, most of them ultimately stayed in Switzerland. Therefore, intentions were a good predictor of behaviors, although life events or administrative constraints (nonrenewal of permits) could in some cases change intentions.

Modeling of Intentions and Behaviors

Logistic regressions were performed to analyze the associations between remigration intentions/behaviors and some determinants or factors identified in the literature review and gathered during the 2016 survey. As explained above, two series of models were developed. The first series of logistic regressions included the factors associated with the intention to leave within the next 2 years, as declared in 2016. The second series identified the factors associated with actual departures observed between 2016 and 2018. Before discussing the results and the coherence between the different models, we note that some of the factors included in the model were likely to change between the date of the survey and the date of departure, for example, due to the end of an educational course, a change in professional position, or a family event. The models therefore tested the associations between the 2016 situations and remigration behaviors and did not take into account these possible changes.

The first model included demographic factors and factors related to migration trajectories, transnational ties, and the institutional context. The models showed good explanatory capacity for both intentions and behaviors. The addition of variables related to economic activity (model 2) improved this capacity and made it possible to highlight some additional statistically significant associations without modifying the parameters obtained in the first model. The inclusion of determinants of social integration and perceptions of acceptance (model 3) also increased the explanatory capacity without changing the previously obtained parameters. For this reason, to facilitate the reading of the results, we preferred model 3.

The factors significantly associated with remigration intentions (Table 4) were consistent with the determinants identified in the literature. However, demographic and family-related factors were not significantly associated with intentions. Rather, the migration trajectory played an important role. First, a lower level of intentions was observed for those who were aged between 35 and 44 at the time of their arrival than for those aged between 25 and 34. This finding suggests that immigration to Switzerland later in life corresponds to an intention to stay longer or permanently in the country, indicating that an advanced age impacts the intention to stay. This effect can be explained by the fact that mobility tends to decrease as age increases (for instance, for Switzerland, see Pecoraro 2012, Fioretta and Wanner 2017). Second, the reason for migration also played an obvious role. Compared to migrants who arrived in Switzerland for work purposes only, those who arrived for family or other reasons had lower intentions to leave.

Factors related to transnational ties also played an important role in influencing whether migrants decided to leave Switzerland. In particular, having one or more close family members (spouse or children) who lived abroad, which had an odds ratio close to 2, and having visited the country of origin were both associated with the intention to return.

Factors related to the institutional context were also closely linked to intentions to leave Switzerland. Having a short-term permit had a significant impact on intentions to leave. Notably, logistic regression did not provide information on causality and allowed only a determination of an association between two variables. Thus, a migrant’s intention to stay in Switzerland for a short period of time could result in him or her seeking a short-term permit rather than a more stable permit. In addition, obtaining only a short-term permit could discourage the migrant from pursuing his or her future in Switzerland.

The region of origin was also associated with the intention to migrate in the sense that nationals from non-EU/EFTA OECD countries had higher intentions to leave Switzerland. These people were generally highly qualified and engaged in a professional type of migratory movement. Their stays in Switzerland were often seen as a temporary part of their professional careers.

Some professional trajectory variables were also associated with the intention to leave Switzerland. Labor market status had a particularly strong association, as students and inactive people showed higher intentions to leave than the working population. Higher intentions were also observed for persons who migrated to Switzerland due to a professional transfer. These people were often employed by multinationals and engaged in migratory movement, with little room for the possibility of remaining in Switzerland. On the other hand, the level of education and perceived improvement in professional position as a result of migration were not significantly associated with migration intentions.

Social integration indicators were also significantly associated with migration intentions. Thus, an increased interest in Swiss life (and more specifically in local news) reduced migration intentions, while a decrease in migration satisfaction increased migration intentions. Knowledge of the language also played a role, as anticipated. On the other hand, perceptions of acceptance by the host population were not associated with intentions.

The second series of models addressed remigration behavior. This series showed similar results, with the exception of a few variables that became significantly associated with the dependent variable. First, the absence of a partnership in 2016 was associated with a significant increase in the risk of leaving Switzerland from 2016 to 2018, which is consistent with the literature. The differences between the two series of models are probably explained by the fact that single persons are more able to react to unexpected opportunities abroad due to the absence of family responsibilities.

The presence of a family member in the household significantly reduced the probability of leaving. Notably, compared to the model presented in Table 4, those presented in Table 5 had the same value for the odds ratio and increased significance due to the distribution of responses. The same effect was observed for the level of education, as having a tertiary level was associated with a significantly lower risk of leaving Switzerland, but the odds ratio remained the same as that obtained in the previous model.

Moreover, the length of stay was significantly associated with the probability of leaving the country, even though it was not associated with intentions. A short period of stay in Switzerland led to increased mobility.

A final difference between the two series of models was related to the impact of professional development. People who reported an improvement in their employment situation as a result of migration were less likely to emigrate, a result that was not observed with regard to intentions.

The results for the other factors were confirmed.

Discussion and Conclusion

Overall, this paper demonstrates that declared intentions are a good predictor of remigration among recent immigrants, which confirms the findings of Van Dalen and Henkens (2008) on the native (Dutch) population. The relationship between migrants’ intentions and behaviors is even stronger in our case. This result can be easily explained by the fact that we focused on the migrant population, who is more directly experienced with international mobility than Dutch natives and therefore can declare more realistic intentions.

The variables influencing intentions and behaviors are almost the same. They are related to the migration trajectory, ties with the country of origin, the institutional context, professional life, and social integration. The demographic and family dimensions that were included in the models do not impact intentions to leave Switzerland but do slightly impact behaviors, which confirms the results observed by Pecoraro (2012). The results are consistent with the literature on the determinants of remigration intentions and behaviors among migrants (van Dalen and Henkens 2008; de Haas and Fokkema 2011).

Almost all the determinants of remigration behaviors are also determinants of intentions, which not only demonstrates the strong association between the two dimensions but also shows that a large part of the immigrants living in Switzerland are able to realize their desires for return or onward migration or staying in Switzerland. The regime of free circulation that characterizes European countries is certainly one reason explaining this situation. However, it is probable that some respondents provided answers regarding their intentions that were influenced by their ability to stay in Switzerland rather than their personal desires.

Notably, 40% of the target population immigrated to Switzerland with a job contract (Wanner 2019), which indicates that their arrival in Switzerland was voluntary and suggests that the choice to stay or leave the country can probably be made more openly and freely in Switzerland than in other contexts.

There are a few limitations of the study related to the use of survey data. On the one hand, selection effects cannot be ruled out, as foreigners who are less well integrated in society are generally more difficult to reach by a survey. It is therefore possible that the participants were among the most integrate migrants in Switzerland and were thus affected little by integration difficulties and were less likely to leave Switzerland contrary to their intentions. On the other hand, the intentions expressed in a survey regarding the future may be influenced by personal feelings as well as often imperfect knowledge of the possibilities of staying in a country. Among the foreigners who declare remigration intentions, we were unable to distinguish between those who responded in this way because they had no alternative, given their personal situation (permit about to expire, for example) and those who expressed a personal desire for remigration.

Despite these limitations, some results, especially the differences observed between the models, can be discussed more in depth.

A first surprising result is that in Switzerland, the length of time since immigration does not influence remigration intentions but does influence remigration behaviors. These divergent results could be explained by the difficulty of staying in Switzerland for certain groups of newly arrived persons, which is linked to the difficulty ensuring a resident status with a medium- or long-term permit. However, it cannot be ruled out that recent migrants may initially view Switzerland very positively before reflecting on their feelings and possibly changing their minds after some time.

Moreover, while the family situation does not play a role in intentions for return migration or departure from Switzerland, it slightly influences return behavior. As mentioned by other authors (Steinmann 2019; van Dalen and Henkens 2013; Harvey 2009), being involved in a conjugal relationship and sharing accommodations with a spouse reduce the probability of leaving the host country. The lack of significant effects of these variables on intentions probably indicates that departure may not necessarily be immediately achievable. Departure is a stage with many consequences for family life as well as professional life. Interestingly, people who report improvements in their professional situations as a result of migration have similar levels of intentions to leave as people who have not made any progress. On the other hand, their probability of leaving is significantly lower, which is certainly explained by the fact that the realization of the intention to leave requires the migrant to confront the potential cost of leaving and represents an occupational risk that he or she may not be ready to take.

In addition, the results show lower levels of intentions to leave and actual departure from Switzerland among the migrants who arrived when they were between 35 and 44 years old, i.e., at an age characterized by a gradual decrease in residential mobility. However, those who arrived at 45 years old or older show higher rates of actual departure and intentions to leave the country, similar to the youngest age group. This finding can be explained by the fact that older immigrants face difficulties living as retirees in Switzerland due to the high costs of living. Part of the retirement benefits are composed of the first pillar, for which the amount depends on the duration of work in Switzerland, and the other part is composed of the second pillar, which is capital accumulated throughout one’s working life. For migrants arriving after the age of 45, the retirement benefits generally do not allow them to live in Switzerland with the same standard of living as in their own countries. Moreover, some fiscal incentives may also push migrants, especially those who are tenants of lands or housing in their countries of origin, to leave Switzerland; in particular, the development of the automatic exchange of information (AEOI) within European countries can lead to the return of tenants who did not declare their properties abroad.

Finally, perceptions of being a victim of discriminatory behavior do not influence intentions or actual remigration, a result that contradicts that of Pungas et al. (2012) in Finland. The hypothesis that perceptions of acceptance by the host population lead to remigration must be ruled out. Switzerland is characterized by local migration, and discrimination, although real, only concerns minority groups. For the majority of migrants interviewed, the feeling of discrimination did not influence intentions or remigration, probably because this discrimination does not hinder or only slightly hinders professional integration.

Overall, the rather high level of coherence between the two series of models shows that intentions can be a good predictor of behaviors and, by extension, the level of remigration. Intentions reflected respondents’ personal feelings at the time of the survey and sometimes reflected their potential to remain in Switzerland from a legal point of view. On the other hand, behaviors are more rational in the sense that migrants’ reflections on their actual situations seem to be more profound, and their choices to stay in Switzerland or to leave are thus influenced by rational elements such as their labor market situation or family constraints.

Finally, to answer the question posed in the title of this article, it is likely that migrants’ intentions to return to or depart from their countries of origin represent a way to predict future remigration with a relatively high level of credibility, at least in the short term. The factors associated with these two dimensions are similar, although some variations were observed in the models that were constructed. This similarity offers a way to improve the forecasting of remigration flows from the collection of information from migrants on their short- and medium-term intentions.

Notes

Authors’ own computation based on the STATPOP register.

https://www.pordata.pt/en/Europe/Gross+emigration+rate-1935 based on https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/en/web/products-datasets/-/TPS00177. Consulted 20 August 2019.

The reason for absence was not available. We assumed that the respondents who were not residents 2 years after the survey had left Switzerland. Cases of death were also possible but, based on the age structure of the sample, they can be considered insignificant.

Short-term permits are, in principle, not renewable, while annual and permanent permits are automatically renewable, except in exceptional circumstances.

References

Armitage, C. J., & Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: a meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(4), 471–499.

Bachmeier, J., Lessard-Phillips, L., & Fokkema, T. (2013). The gendered dynamics of integration and transnational engagement among second-generation adults in Europe. In L. Oso & N. Ribas Mateos (Eds.), International handbook on gender, migration and transnationalism (pp. 268–293). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Borjas, G. J. (1989). Immigrant and emigrant earnings: a longitudinal study. Economic Inquiry, 27(1), 21–37.

Borjas, G. J., & Bratsberg, B. (1996). Who leaves? The outmigration of the foreign-born. Review of Economics and Statistics, 78(1), 165–176.

Carling, J. (2014). The role of aspirations in migration. Oxford: University of Oxford https://jorgencarling.org/2014/09/23/the-role-of-aspirations-in-migration/. Accessed 23 August 2019.

Carling, J. (2017). How does migration arise? In M. McAuliffe & M. Klein Solomon (Eds.), Ideas to inform international cooperation on safe, orderly and regular migration. Geneva: IOM.

Carling, J., & Pettersen, S. V. (2014). Return migration intentions in the integration–transnationalism matrix. International Migration, 52, 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12161.

Cassarino, J.-P. (2004). Theorising return migration: the conceptual approach to return migrants revisited. International Journal on Multicultural Studies, 6(2), 253–279.

Cerase, F. P. (1974). Expectations and reality: a case study of return migration from the United States to Southern Italy. International Migration Review, 8(2), 245–262.

Constant, A., & Massey, D. S. (2002). Return migration by German guestworkers: neoclassical versus new economic theories. International Migration, 40, 5–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2435.00204.

Constant, A., & Massey, D. S. (2003). Self-selection, earnings, and out-migration: a longitudinal study of immigrants to Germany. Journal of Population Economics, 16(4), 631–653.

Coulter, R., van Ham, M., & Feijten, P. (2011). A longitudinal analysis of moving desires, expectations and actual moving behavior. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 43, 2742–2760. https://doi.org/10.1068/a44105.

Cox, D. R., & Snell, E. J. (1989). Analysis of binary data. London: Chapman and Hall/CRC Press 240 p.

Creighton, M. J. (2013). The role of aspirations in domestic and international migration. The Social Science Journal, 50, 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2012.07.006.

D’Amato, G., Wanner, P., & Steiner, I. (2019). Today’s migration-mobility nexus in Switzerland. In I. Steiner & P. Wanner (Eds.), Migrants and expats: the Swiss migration and mobility nexus, IMISCOE research series. London: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05671-1_1.

De Haas, H. (2014). Migration theory. Quo Vadis?, Oxford: DEMIG project paper 24. https://www.imi.ox.ac.uk/publications/wp-100-14. Accessed 23 August 2019.

de Haas, H., & Fokkema, T. (2011). The effects of integration and transnational ties on return migration intentions. Demographic Research, 25, 755–782.

de Haas, H., Fokkema, T., & Fihri, M. F. (2015). Return migration as failure or success? The determinants of return migration intentions among Moroccan migrants in Europe. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 16, 415–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-014-0344-6.

De Jong, G. F. (2000). Expectations, gender, and norms in migration decision-making. Population Studies, 54(3), 307–319.

de Vroome, T., & Tubergen, F. (2014). Settlement intentions of recently arrived immigrants and refugees in the Netherlands. Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies, 12, 47–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2013.810798.

Docquier, F., Peri, G., & Ruyssen, I. (2014). The cross-country determinants of potential and actual migration. International Migration Review, 48, S37–S99.

Dustmann, C. (1996). Return migration: the European experience. Economic Policy, 11, 213. https://doi.org/10.2307/1344525.

Dustmann, C., & Weiss, Y. (2007). Return migration: theory and empirical evidence from the UK. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 45(2), 236–256.

Ette, A., Heß, B., & Sauer, L. (2016). Tackling Germany’s demographic skills shortage: permanent settlement intentions of the recent wave of labor migrants from non-European countries. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 17, 429–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-015-0424-2.

Fioretta, J., Wanner, P. (2017). Rester ou partir ? Les déterminants des flux d’émigration récents depuis la Suisse, Revue européenne des migrations internationale. http://journals.openedition.org/remi/8532. Accessed 23 Aug 2019.

Harvey, W. S. (2009). British and Indian scientists in Boston considering returning to their home countries. Population, Space and Place, 15, 493–508. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.526.

Haug, S. (2008). Migration networks and migration decision-making. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 34(4), 585–605.

Jasso, G., & Rosenzweig, M. R. (1988). How well do U.S. immigrants do? Vintage effects, emigration selectivity and occupational mobility of immigrants. In P. T. Schulz (Ed.), Research of population economics (pp. 229–253). Greenwich: JAI Press.

Laczko, F., Tjaden, J. D., & Auer, D. (2017). Measuring Global Migration Potential, 2010–2015. International organisation for migration. Global Migration Data Analysis Centre - Data Briefing Series, 9(1), 1–14 https://reliefweb.int/report/world/global-migration-data-analysis-centre-data-briefing-series-issue-no-9-july-2017. Accessed 23 Aug 2019.

Mak, A. S. (1997). Skilled Hong Kong immigrants’ intention to repatriate. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, 6, 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/011719689700600202.

Massey, D. S. (1987). Understanding Mexican migration to the United States. American Journal of Sociology, 92, 1332–1403.

Massey, D. S., & Akresh, I. R. (2006). Immigrant intentions and mobility in a global economy: the attitudes and behavior of recently arrived US immigrants. Social Science Quarterly, 87, 954–971. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2006.00410.x.

Migali, S. & Scipioni, M. (2018). A global analysis of intentions to migrate, European Commission. JRC Science Hub. https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/sites/jrcsh/files/technical_report_on_gallup_v7_finalpubsy.pdf. Accessed 29 Aug 2019.

OECD. (2008). Partie III, les migrations de retour : un nouveau regard. In OCDE (Ed.), Perspectives des migrations internationales (pp. 181–246). Paris: OCDE, SOPEMI.

Paparusso, A., & Ambrosetti, E. (2017). To stay or to return? Return migration intentions of Moroccans in Italy. International Migration, 55, 137–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12375.

Pecoraro, M. (2012). Rester ou partir: les déterminants de l’émigration hors de Suisse. In P. Wanner (Ed.), La démographie des étrangers en Suisse (pp. 141–155). Genève: Seismo.

Pungas E., Toomet O, & Tammaru T. & Anniste K. (2012). Are better educated migrants returning? Evidence from multi-dimensional education data, Norface Discussion Paper Series, Norface Research Programme on Migration, Department of Economics, University College London. https://ideas.repec.org/p/nor/wpaper/2012018.html. Accessed 23 Aug 2019.

Rodriguez, V., & Egea, C. (2006). Return and the social environment of Andalusian emigrants in Europe. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 32, 1377–1393. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830600928771.

Sapeha, H. (2017). Migrants’ intention to move or stay in their initial destination. International Migration, 55, 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12304.

SEM. (2020). Statistique des étrangers et de l’asile. Bern: Secrétariat aux migrations https://www.sem.admin.ch/sem/fr/home/publiservice/statistik.html. Accessed 25 Sept 2020.

Snel, E., Faber, M., & Engbersen, G. (2015). To stay or return? Explaining return intentions of Central and Eastern European labor migrants. Central and Eastern European Migration Review, 4(2), 5–24.

Stark, O. (1991). The migration of labor. Cambridge: Basil Blackwell.

Steiner, I. (2019). Immigrants’ intentions–leaning towards remigration or naturalization? In I. Steiner & P. Wanner (Eds.), Migrants and expats: the Swiss migration and mobility nexus, IMISCOE Research Series. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05671-1_12.

Steiner, V., & Velling, J. (1992). Re-migration behaviour and expected duration of stay of guest-workers in Germany. ZEW Discussion Papers, 92-14. https://www.zew.de/en/publikationen/re-migration-behaviour-and-expected-duration-of-stay-of-guest-workers-in-germany/?cHash=05388c8d5649efba2d4ef98b9d6fcc83. Accessed 23 Aug 2019.

Steiner, I., & Wanner, P. (2019). Migrants and expats: the Swiss migration and mobility nexus, IMISCOE Research Series. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05671-1.

Steinmann, J. P. (2019). One-way or return? Explaining group-specific return intentions of recently arrived Polish and Turkish immigrants in Germany. Migration Studies, 7, 117–151. https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnx073.

Tjaden, J., Auer, D., & Laczko, F. (2019). Linking migration intentions with flows: evidence and potential use. International Migration. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12502.

van Baalen, B., & Müller, T. (2009). Return intentions of temporary migrants: the case of Germany. Paper presented at the Second Conference of Transnationality of Migrants, Louvain, 23-24 January. http://www.cepr.org/meets/wkcn/2/2395/papers/MuellerFinal.pdf. Accessed 23 Aug 2019.

van Dalen, H. P., & Henkens, K. (2008). Emigration intentions: mere words or true plans? Explaining international migration intentions and behavior. SSRN. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1153985.

van Dalen, H. P., & Henkens, K. (2013). Explaining emigration intentions and behaviour in the Netherlands, 2005–10. Population Studies: A Journal of Demography, 67, 225–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2012.725135.

van den Berg, G. J., & Weynandt, M. A. (2012), Explaining differences between the expected and actual duration until return migration: economic changes. SOEPpaper https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2172696.

Waldorf, B. (1995). Determinants of international return migration intentions. The Professional Geographer, 47(2), 125–136.

Wanner, P. (2019). Integration of recently arrived migrants in the Swiss labour market–do the reasons for migration matter? In I. Steiner & P. Wanner (Eds.), Migrants and expats: the Swiss migration and mobility nexus, IMISCOE Research Series. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05671-1_5.

Zlotnik, H. (2006). Theories of international migration. In G. Caselli, J. Vallin, & G. Wunsch (Eds.), Demography analysis and synthesis. A Treatie in population (pp. 293–306). Burlington: Elsevier.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by University of Geneva. This research was supported by the National Center of Competence in Research nccr – on the move funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wanner, P. Can Migrants’ Emigration Intentions Predict Their Actual Behaviors? Evidence from a Swiss Survey. Int. Migration & Integration 22, 1151–1179 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-020-00798-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-020-00798-7