Abstract

Although an increasing number of studies emphasise migrants’ lack of knowledge about their childcare rights as a crucial barrier to their childcare usage, almost none examines the conditions under which migrant families acquire this knowledge. This study contributes to the literature by exploring potential individual factors determining migrant families’ knowledge about their childcare rights in Germany. I use unique data collected through the project Migrants’ Welfare State Attitudes (MIFARE), in which nine different migrant groups in Germany were surveyed about their relation to the welfare state, including childcare. Analysing a total sample of 623 migrants living with children in their household and by using logistic regression analyses, I find that human and social capital play significant roles in explaining migrants’ knowledge about their childcare rights. Migrants who speak the host language sufficiently are more likely to know about their childcare rights; however, it does not matter whether migrants are lower or higher educated. Moreover, I observe that migrants benefit from their co-ethnic relations only if childcare usage is high among their ethnic group. Based on these results, policy recommendations are discussed in order to increase migrants’ knowledge about their childcare rights in Germany.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Formal childcare provided by the government or private institutions is a central pillar of the European Union’s (EU) ‘social investment strategy’ and has been championed by the EU, national and local governments across Europe as an inclusive way to promote growth and reduce inequality. Childcare in Germany is a public good and in line with the European Union’s investment strategy; Germany expanded formal childcare immensely over the last decade, greatly subsidising childcare costs (OECD 2016b). The goal is to improve female participation in the labour market as well as social inclusion of children from disadvantaged backgrounds, especially migrants (Cantillon 2011; Esping-Andersen 2002). Whereas participation rates in formal childcare indeed increased, migrant parents stand out as they still make significantly less use of formal childcare than native parents, despite comparatively low costs (Destatis 2018; Frauke and Spiess 2015).

Next to migrants’ lower socio-economic status and socialisation in traditional family models (Pfau-Effinger 2005), recent studies emphasise migrants’ unfamiliarity with the receiving country’s childcare system and their rights within it as a major barrier to formal childcare access (Karoly et al. 2018; Miller et al. 2014; Vesely 2013). Refusal of formal childcare due to personal preferences is a personal choice that ought to be respected. If, however, migrants do not make use of formal childcare due to lack of knowledge, policy makers should act for two reasons. First, non-use of formal childcare is mainly carried out on the backs of mothers, who remain the main caretakers of children (Boeckmann et al. 2014). Non-participation in the labour market adds to the double disadvantage migrant women already experience in receiving countries (Ballarino and Panichella 2018; Boeckmann et al. 2014). Second, recent research shows that migrant children in particular benefit from formal childcare as it positively affects their language skills and cognitive abilities (Becker 2010; Drange and Telle 2015; Klein and Sonntag 2017; Magnuson and Madison 2006; Roßbach et al. 2009; Waldfogel 2006). Hence, formal childcare indeed facilitates the integration chances of the weakest in society, namely migrant women and children. However, in spite of the alarming consequences of such lack of knowledge for migrants’ integration chances, there is also a good side to the story from a policy perspective: while it is proving difficult and ethically debatable to influence people’s family values, disinformation can be tackled if reasons are known. It is therefore crucial to explore the reasons for such lack of knowledge if governments and local decision makers aim to guarantee equal chances of early childhood education for migrants and their children.

Still, despite the general acknowledgement of migrants being disadvantaged due to insufficient knowledge of their childcare rights, we know very little about why this might be the case. The aim of this study is therefore to quantitatively examine which factors contribute to migrant families’ knowledge about their childcare rights. Specifically, I study the extent to which migrants are aware of the legal conditions under which they possess the same rights as natives with regard to accessing formal childcare. I assume that migrants draw on two main resources in order to access knowledge about their childcare rights: human capital and social capital. Whereas migrants with higher levels of education and sufficient German language skills might be better able to understand their childcare rights, migrants might also benefit from their network providing the information.

Drawing on the German Migrants’ Welfare State Attitudes (MIFARE) data (Bekhuis et al. 2018), I examine knowledge about childcare rights from nine different first-generation migrant groups living in West Germany and originating from the US, Great Britain, Spain, Poland, Romania, Turkey, Russia, Japan, and China. The sample analysed consists of a total of 623 migrants, who live with at least one child in the same household. In the following, I first provide an overview of the relevance of formal childcare and its organisation in Germany, followed by a discussion on why knowledge contributes to the ‘civic gain’ of migrants (Morris 2002). I then elaborate on relevant theories and derived hypotheses regarding migrants’ knowledge of their childcare rights. I will continue with presenting the empirical strategy, followed by the results. The article concludes with a discussion of the main findings and implications for childcare policies.

The Relevance of Formal Childcare and Its Organisation in Germany

In contrast to informal childcare, which is mainly provided by parents, relatives, or friends, formal childcare is provided by the government or private institutions and includes ‘care outside the child’s home, trained providers, extensive peer interaction and an overt focus on development and learning’ (Gottfried and Kim 2015, p.86). Academics and policy advisors see two main advantages of formal childcare, particularly for the migrant community. First, research consistently shows that migrant children in Germany who visit formal childcare benefit not only in terms of educational attainment (Seyda 2009) but also with regard to their language development; regular contact with native children as well as pedagogically trained staff improves German language skills of these children significantly (Becker 2010; Klein and Sonntag 2017), and the effect is stronger the younger the children are when visiting formal childcare institutions (Peisner‐Feinberg et al. 2001). Hence, formal childcare is viewed as crucial for preventing ethnic inequalities in later life. Second, formal childcare is considered key for female labour market participation (Bauernschuster and Schlotter 2015; Boeckmann et al. 2014), particularly if the childcare is of high quality (Schober and Spiess 2015). Migrant women are particularly at risk of non-employment (Ballarino and Panichella 2018), and formal childcare can therefore alleviate existing disadvantageous structures to which migrant women are exposed.

The organisation of formal childcare has changed significantly over the last decades, particularly in West Germany. Unlike in the former GDR, where the use of formal childcare was common practice, West Germany followed the traditional bread-winner/housewife model with fathers being responsible for the household income, and mothers for taking care of home and children. Between the 1960s and 1980s, the German family culture has, however, shifted from the dominant housewife model to the male breadwinner/female part-time worker model (Pfau-Effinger 2012), leading to a significant extension of childcare provision for children under the age of three. Since 2013, Germany follows a universal childcare approach and every child after the age of one has the legal right to attend formal childcare.

The focus thereby is not only on the availability of formal childcare but also on its costs and quality. In contrast to countries where childcare is organised privately (for example, the Netherlands, Switzerland, or the UK), childcare in Germany is considered a public good. As a result, childcare costs are comparatively low due to government-based subsidies (OECD 2016b) which lower financial barriers particularly for low-income parents (Zoch and Hondralis 2017) and increase the likelihood for female participation in the labour market (Morrissey 2017). Parents receiving social assistance, for example, do not have to pay anything for childcare. However, differences exist between federal states (Bundesländer) and communities (Scholz et al. 2019) and in some federal states, formal childcare is even free, regardless of the parents’ income.Footnote 1 It is therefore reasonable to assume that the low participation rates among migrants cannot solely be attributed to costs. Rather, other factors such as lack of knowledge might explain why migrant families do not use formal childcare as frequently as natives. Moreover, migrants who do not possess knowledge about their social rights might also not be fully informed about costs of childcare. This would mean that the government’s efforts to make childcare accessible to everyone would not bear full fruit, particularly with regard to groups that would most likely benefit from low childcare costs, such as migrants.

The quality of German childcare is rated well in international comparisons. Germany is above the OECD average in number of children per staff, annual expenditure per student, and qualification of practitioners (OECD 2016a). For example, the average child to contact-staff ratio in Germany is 4.6, compared to 6.7 which is the average within the European Union (OECD 2016a).The overall high quality of formal childcare in Germany leads to positive effects for the children, particularly for those with migration background, as described above.

Germany has thereby followed the European Union’s Social Investment Strategy ‘aimed at strengthening people’s current and future capacities, and by this, helping to “prepare” to confront life’s risks, rather than simply “repairing” the consequences’ (European Commission 2013, p.3). In 2018, around 33% of all children under the age of three did attend a childcare institution (Destatis 2018). However, numbers differ quite extensively between children with and without migration background, particularly with regard to childcare for very young children: for those under the age of three, 40% of children of German parents visit formal childcare, whereas only 20% of children with migration background do. The ethnic difference becomes smaller the older the children get: among children between the ages of three and six, 99% of children with German parents visit childcare and 82% of children with migration background. Still, this means even among older children the likelihood of migrant parents to make use of formal childcare is 17 percentage points lower than for native parents.

Due to the three-level structure of public policy administration in Germany, formal childcare is governed on the national, regional (the 16 Bundeslaender), and on the local level (municipalities, Kommunen and districts, Landkreise) (Scholz et al. 2019). Each level of governance has specific responsibilities making the organisation of formal childcare very much decentralised and complex. This makes it particularly difficult for migrant parents, who often have been socialised in different childcare regimes, to acquire all the necessary information regarding access and financing formal childcare and to understand the conditions under which they have the same rights herein as their native peers.

Stratification of Migrants’ Welfare Rights: Civic Inclusion Versus Civic Gain

Migrants in Germany are entitled to use formal childcare and apply for financial support as soon as they have registered as residents. Migrant parents therefore enjoy rather quickly the same childcare rights as German parents. However, research in the USA but also in Germany suggests that migrants are often not aware of their entitlements within the receiving country’s childcare system (Karoly et al. 2018; Miller et al. 2014; Schnelle 2013; Scholz et al. 2019; Vesely 2013). The German International Centre Early Childhood Education and Care’s recent report about inequalities in access to early childhood education (Scholz et al. 2019) emphasises that next to cultural factors that drive childcare behaviour, migrant families in Germany are particularly disadvantaged due to language barriers and lack of knowledge of the German childcare system. The Expert Council of German Foundations on Integration and Migration also concludes that policy makers have to take migrants’ unfamiliarity with the host country’s childcare system into account when designing policies aiming at increasing childcare participation rates among migrant families (Schnelle 2013). Research in the USA comes to similar conclusions: Vesely (2013) qualitatively examines childcare experiences among Hispanic and African mothers in the USA and finds that among the 40 mothers interviewed, only 5 (12.5%) possessed knowledge of their eligibility for childcare programmes. Migrant mothers reported that they often were not aware of the governmental support for low-income families to access formal childcare or that they were eligible for accessing such support. Also, Karoly et al. (2018) emphasise the difficulty of formal childcare access due to complex paperwork and long waiting lists (p. 87).

Whether migrants are actually aware of their social rights, including access to formal childcare, largely determines their civic gain within the welfare state. In contrast to civic inclusion, which refers to the formal social rights granted by the government, civic gain depicts the actual realisation of these formal rights (Morris 2002). Both civic inclusion and civic gain contribute to the stratification of migrants’ social rights (Mohr 2005) and influence their integration and life chances within the host society (Söhn 2013). Migrants’ knowledge of their childcare rights is thereby a driving factor in realising the same civic gain as natives, particularly with regard to female labour market participation and integration chances of migrant children (see among others Ballarino and Panichella 2018; Becker 2007; Boeckmann et al. 2014; Drange and Telle 2015). A lack of knowledge of the host country’s childcare system thereby contributes to already existing inequalities between natives and migrants.

It is therefore crucial to understand which factors enable and which potentially hinder migrants to acquire their childcare entitlements. Specifically, I look at the extent to which migrants are aware of their eligibility to use formal childcare to the same extent as natives, or in other words, their knowledge about their childcare rights. I focus thereby on first-generation migrants who are living with at least one child in the same household and who have been socialised in different (non-German) welfare and childcare regimes. Migrant families might acquire knowledge over their childcare via official agencies such as migration centres or childcare facilities or informally via their social network (Bucx and de Roos 2015; Karoly et al. 2018; Ryan et al. 2008; Vesely 2013). Following Renema (2018) and Seibel (2019), I therefore propose that migrants’ childcare rights knowledge is likely to depend on two main factors: their human capital and their social capital. Both forms of capital enable migrants to access and process information on formal childcare and their rights within the German welfare state.

Human Capital

Migrant families raising their children in an unfamiliar context face particular challenges to gain access to full information about the host country’s childcare system and their rights within it. Previous research emphasises the complexity of childcare rights and bureaucracy governing the access to formal childcare (Karoly et al. 2018; Vesely 2013), and the importance of human capital for migrants to overcome these barriers. In particular, insufficient language skills make it difficult to understand childcare organisation in the host country (Karoly et al. 2018; Schnelle 2013; Vesely 2013). Most information websites are in German, particularly at the municipality level. Webpages provided in English or other languages are mainly targeted at high-skilled workers and do not necessarily reach other migrant groups. Hence, migrants with sufficient German language skills are likely to be better able to navigate through the German childcare system and to acquire knowledge of their rights.

Next to language skills, migrants’ education is likely to affect their likelihood of acquiring the right information about their childcare rights. Education can be viewed as an indicator of migrants’ cognitive ability to understand the complexity of formal childcare organisation and the conditions under which they are eligible to access formal childcare (Kingston et al. 2003). However, education and language skills may also influence migrants’ self-interest in formal childcare. According to the self-interest argument, people tend to reflect differently on specific welfare programmes depending on the extent to which they are directly affected by the programme (Andreß and Heien 2001). The self-interest assumption has so far mainly been applied to the field of welfare state attitudes, showing that people who directly benefit from certain welfare programmes are more likely to hold positive attitudes towards these programmes (Andreß and Heien 2001; Seibel and Hedegaard 2017; van Oorschot 2006). However, a similar assumption can be made with regard to knowledge about welfare rights (Seibel 2019), including childcare rights of migrants. The need to use childcare might foster a general interest in the topic and increases the likelihood of making an effort to become informed about it. Studies show that higher educated parents in particular make use of formal childcare (Kahn and Greenberg 2015; Krapf 2014; Van Gameren 2013), due to high opportunity costs when leaving the labour market (Krapf 2014). Moreover, whereas migrant parents with little education tend to be unaware of the beneficial effects of formal childcare for their children’s subsequent school achievement (Karoly et al. 2018), higher educated parents are found to value the developmental effect of childcare (Mamolo et al. 2011). Hence, education might have a positive effect on migrants’ self-interest in formal childcare and therefore strengthen their efforts to acquire full information on their childcare rights. A similar argument was provided by Miller et al. (2014) with regard to language skills: migrants with insufficient language skills might prefer same-language care for their children which is more likely to be provided via informal care, thereby decreasing their interest to become informed about their formal childcare rights.

Although to my knowledge no study has quantitatively tested these assumptions, qualitative research supports the notion that language skills and education are crucial for migrants’ chances to acquire information and knowledge about their childcare rights (Kahn and Greenberg 2015; Lastikka and Lipponen 2016; Vesely 2013). With regard to other welfare rights, language skills and education among migrants have been shown to be main determinants of their likelihood to possess adequate knowledge about their rights (Renema 2018; Seibel 2019). I therefore hypothesise that:

-

H1: The better the language skills and the higher the level of education, the more likely migrants know about their childcare rights.

Social Capital

Some studies suggest that it is less the migrants’ human capital but more their access to certain social networks that provides them with the relevant childcare information (see, for example, Karoly et al. 2018). According to social capital theory, social networks provide their members with specific resources, called social capital, which include trusted information and knowledge (Coleman 1988). Previous research suggests that migrants might actually rely predominately on their social network for information acquisition about formal childcare (Bucx and de Roos 2015; Karoly et al. 2018; Vesely 2013). Research in related fields conclude that social networks are crucial for parents’ spectrum of childcare knowledge. Dahl et al. (2014), for example, find that relevant knowledge about paternity leave policies in Norway is mainly acquired through peer networks, which transmit information about the costs and benefits of the programme.

Research in the field of childcare suggests that migrants might benefit particularly from contact with their own co-ethnic group, so-called bonding ties (Karoly et al. 2018; Vesely 2013). Co-ethnic ties are still one of the main reasons, next to finding work, why people migrate (Fawcett 1989; Massey et al. 1993; OECD 2017), and research has shown the importance of these ties for social, informational, and practical support within the receiving country (Bilecen et al. 2018). The general notion that co-ethnic relations provide access to trusted information (Flap 2003; Portes and Sensenbrenner 1993) is confirmed by qualitative research on migrants and their access to formal childcare, showing that migrants indeed receive childcare information primarily through their co-ethnic network (Bucx and de Roos 2015; Karoly et al. 2018; Ryan et al. 2008; Vesely 2013). Reasons are often insufficient language skills which impede the use of alternative information sources such as childcare centres, or the preference of migrant parents to receive information from co-ethnics who are familiar with culture-specific requests and worries. One can argue, of course, that the simple fact that migrants turn to their co-ethnic community for information gathering does not mean that these networks are indeed the best to provide such information. A large body of research has actually shown that migrants benefit more from social relations with natives rather than with co-ethnics, particularly for labour market integration (Griesshaber and Seibel 2015; Lancee 2010) due to natives’ greater familiarity with the host country’s institutions and services (Aguilera 2005). Natives might indeed be better informed about the general organisation of childcare in the host country, its costs and application procedures; however, it is unlikely that natives are familiar with migrants’ rights within the childcare system and the conditions under which migrants are eligible to access formal childcare. In this context, it is therefore indeed likely that migrants benefit particularly from contact with co-ethnics for knowledge acquisition about childcare rights.

-

H2a: The more ties to co-ethnics, the greater the likelihood of migrants possessing knowledge about their childcare rights.

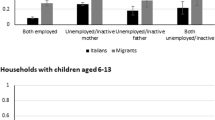

However, whether migrants benefit from their co-ethnic network might depend strongly on the characteristics of these networks. Childcare is an important topic to people during a comparatively short period within their life course. It therefore might matter greatly whether co-ethnic peers have children themselves and are therefore familiar with formal childcare in the receiving country. Research indicates that migrants’ knowledge about specific welfare benefits and programmes, such as formal childcare, strongly depends on migrants’ stage in the life course (De Jong 2019; de Jong and de Valk 2018). The majority of migrants only start to reflect on formal childcare once they are about to become parents themselves. This might be particularly the case for migrants who have to make a greater effort than natives to become informed about their social rights and may do so only if really in need of formal childcare. The graph in Fig. 1 shows that the topic childcare is more relevant for some migrant groups than for others.

Whereas around 30% percent of migrants from the USA or Great Britain report that either they or family members within Germany make use of formal childcare, this is the case for only around 11% of Japanese migrants. Reasons for these group differences certainly lie in the demographic compositions (age, income, number of children) of the groups; however, group differences in gender values and attitudes towards formal childcare are also likely to play a role. Independent of the reasons for these group differences, the ethnic group composition matters in the question of formal childcare usage, since the composition affects migrants’ opportunity to have contact with ethnic peers who are familiar with childcare in Germany. Migrants who belong to an ethnic group which largely makes use of formal childcare are more likely to have contact with ethnic peers who use formal childcare and who are best able to provide migrant parents with the relevant information. In summary, I hypothesise that:

-

H2b: The effect of contact with co-ethnics on migrants' knowledge about their childcare rights is stronger, the more formal childcare is used within the migrants’ ethnic group.

Data, Methods, and Measurements

Data

To answer my research question, I make use of the German data from the survey Migrants’ Welfare State Attitudes (MIFARE). The MIFARE data was collected in the years 2015–2016 among nine different migrant groups from Eastern Europe (Russia, Poland, Rumania), Western Europe (Great Britain, Spain, USA), Asia (Japan and China), and Turkey. All migrants surveyed were born in their country of origin and were 18 years or older at the time the survey was conducted (Bekhuis et al. 2018). Representative samples were drawn via municipalities based on the distribution of these migrant groups in Germany. Respondents were approached with a written invitation letter containing the questionnaire as well as a link to a webpage, where the survey could be filled out online. Among all migrant groups, the majority of respondents opted for answering the questionnaire handwritten on the hard copy. Moreover, respondents had the choice to answer the questionnaire either in the main language of their country of origin, or in German. This provided all migrants (who were literate at least in the main language of their country of origin) the opportunity to participate in the survey.

Only migrants living with at least one child within their household were selected into the sample, which also includes children above the age of 18. These cases were kept for three reasons. First, the sample size is already limited and dropping these cases would result in loss of statistical power. Second and more importantly, having a child of whatever age does indicate that the respondent had to deal with childcare at some point. Third, the focus of this paper lies on migrant families’ knowledge of childcare rights which also include grandparents who play, at least in some migrant groups, a significant role in childcare (Barglowski et al. 2015; Faist et al. 2015) and their knowledge about childcare rights is relevant for certain decision making. Because the data unfortunately do not contain information on the presence of grandchildren, older children living in the household might serve as a proxy for grandchildren in the household.

Because in this study the focus lies on migrants who have been socialised in different childcare regimes and are therefore less familiar with the German welfare state (including formal childcare services), migrants who came to Germany before the age of 16 were dropped from the analyses. After list-wise deletion, the final sample contains 623 first-generation migrants living with at least one child in the household.

Measurements

The dependent variable knowledge childcare rights captures the extent to which migrants know about their rights regarding their access to formal childcare in Germany. This factor is measured by the question ‘At which point after arrival do migrants from [country of origin] have the same rights as natives in Germany to use formal childcare?’ The answer categories include ‘after registering as resident in Germany’ (1); ‘after residing in Germany for an extended period of time, whether or not they have worked’ (2); ‘only after they have worked and paid taxes and insurances for an extended period of time’ (3); ‘once they have become a German citizen (obtained nationality)’ (4); and ‘they will never get the same rights’ (5). For Germany, the correct answer is ‘after registering as resident’ (1). The variable was therefore recoded into a dichotomous variable with ‘not provided correct answer’ (0) and ‘correct answer’ (1).

For human capital I look at migrants’ education and their language skills. Education was measured by the highest educational level achieved (either in the country of origin or receiving country). The answer categories vary between origin groups as educational systems differ between countries. Following standardised international surveys such as the ISSP, responses were therefore recoded according to the ISCED-97 scale (OECD/Eurostat/UNESCO Institute for Statistics 2015) and vary from ‘no formal education [ISCED 0]’ (0) to ‘upper tertiary education [ISCED 6]’ (6).

Respondents also were asked to report their ability to both write and speak the receiving country’s language, from ‘very well’ (1) to ‘not at all’ (5). I reversed the scale and took the mean of both measures; hence, the higher the value, the better the subjective language skills of the respondent.

Social capital was measured by asking about the ethnic composition of respondents’ friendship networks. By asking about friendships, potential ethnic-related tensions, which might bias the exchange of information within the network, are unlikely. Respondents indicated how many of their friends living in the receiving country are originally from their origin country with answer categories ranging from ‘all’ (1) to ‘none’ (5). I reversed the scale so that a higher number indicates a higher share of co-ethnic friends. I further took the mean score of childcare usage per migrant group to measure childcare-related social capital.

Lastly, I control for the following characteristics: employment status (0 = unemployed; 1 = employed), household income (scale between 1 and 11, resembling the wave 2008 of the ISSP’s family income variable), age, years of stay since migration (in years), gender, and gender role attitudes (1 = very traditional to 5 = very liberal), and whether at least one child in the household is under the age of seven.

Results

Description of the Sample

Figure 2 presents for each migrant group the overall percentage that provided the right answer to the childcare rights question. Although the majority of migrants living with children do know about their childcare rights, an alarmingly high number are still not aware of their rights. Whereas among Russian migrants over 83% do know that their ethnic group is eligible to access formal childcare immediately after registering as resident in Germany, this is the case for only 54% of migrants from China. Also among most other migrant groups over 30% of those living with children do not know their childcare rights.

Table 1 provides further descriptives of the main independent variables and control variables for each migrant group. On a scale from one to five, migrants from Romania possess the highest and migrants from Japan the lowest language skills. Also, the level of education varies quite strongly among migrant groups: migrants from Spain, Great Britain, Japan, USA, and China possess on average a higher educational level than post-secondary, non-tertiary education.

Migrants from Turkey and Poland, however, do not possess on average a higher educational level than upper secondary education. With regard to share of co-ethnic friends, we see that migrants from Russia, Turkey, Poland, and Romania have a higher share of co-ethnic friends than migrants from Spain, Great Britain, or the USA. Also, as already presented in Fig. 1, the share of migrants using formal childcare differs across migrant groups. Whereas among migrants from Russia, Great Britain, and the USA over 30% of migrants use formal childcare or have family members in Germany using formal childcare, this is only the case for 17% of migrants from Spain and Turkey and only 11% of migrants from Japan.

Main Analyses

How can we explain that a significant share of migrants are not informed about their childcare rights? The literature emphasises two important factors. On the one hand, a significant number of migrants do not possess sufficient language skills and the needed education in order to understand the complex bureaucracy of formal childcare in Germany. On the other hand, migrants might not be embedded in the ‘right’ networks which contain relevant information about migrants’ formal childcare rights. Table 2 displays the main results (presented in odds ratios) of the effects of migrants’ human and social capital on the likelihood of possessing correct knowledge about their childcare rights. Model A contains the human capital variables. We see that independent of the migration background, the better the language skills of migrants, the more likely they are to know about their childcare rights. The effect of education, though positive, is not significant. Several robustness checks were applied in order to test the validity of the education effect. The same model was estimated using education as a categorical variable; however, the results do not differ. Also, an interaction effect with migration background was estimated (not presented here) showing that the education effect is indeed not significant for most migrant groups except for the Turkish population. Among first-generation Turkish migrants, a higher level of education indeed increases the likelihood of possessing knowledge about their childcare rights.

In model B the social capital hypothesis was tested. I assumed that migrants who are well embedded within their co-ethnic community are more likely to know under which conditions their ethnic group is entitled to access formal childcare in Germany. The results indicate indeed a positive effect of co-ethnic friends on knowledge about childcare rights; however, the effect is not significant. To check the robustness of this result, the social capital variable was also inserted into the model as a categorical variable (not presented here) in order to better capture the variation in the variable, but results did not differ. Hence, hypothesis 2b has to be rejected. However, it can be argued that it is not so much about co-ethnic contact per se, but about social ties to the ‘right’ co-ethnic network (H2b). Migrants might benefit specifically from their co-ethnic ties if these themselves have experience with the German childcare system and therefore can transmit this specialised knowledge to their migrant peers. Therefore, an interaction effect with share of co-ethnic friends and the share of childcare use within the specific ethnic group was estimated (Model C). The assumption was that only those migrants who have a strong probability to have contact with co-ethnics who also use formal childcare or who know people using formal childcare are likely to benefit from this network. We see that the co-ethnic friendship effect becomes negative; however, it increases significantly if migrants belong to a migrant group where formal childcare use is common. To further investigate this pattern, marginal average effects were estimated for each migrant group categorised according to the average formal childcare usage, and presented in Fig. 3.

There is a clear linear effect showing that co-ethnic contact indeed increases the likelihood of childcare rights knowledge if at least 25–30% of the respective ethnic group already makes use of formal childcare. This suggests that the more childcare is being used in the own ethnic group, the higher the chances that co-ethnic friends also either make use of formal childcare or know people who do so. This in turn is likely to increase respondents’ access to knowledge about migrants’ specific rights in the childcare system. Linking these results to Fig. 1 and Table 1, where the average childcare use per ethnic group was presented, we can conclude that in the context of these nine migrant groups, particularly migrants from Russia, the UK, and the USA benefit from their co-ethnic network.

A short overview of the control variables suggests the following: the general assumption that the more liberal gender values migrants hold, the more likely they are to know about their childcare rights does not hold. The effect is actually negative, though not significant. Also, having a child under the age of 7 does not increase the knowledge about migrants’ childcare rights. This is at first surprising since those migrants are generally at a life stage where formal childcare is most crucial; on the other hand, migrants with older children also once had to deal with childcare issues and might therefore know the same about migrants’ childcare rights as do migrants living with small children. Following the self-interest hypothesis (Andreß and Heien 2001), employment and income were also expected to impact migrant parents’ childcare rights knowledge. Employed migrant parents are more in need of formal childcare and therefore might put more effort into acquiring knowledge about their childcare rights. Also, a higher income can translate into a stronger interest in formal childcare since formal childcare is affordable. Being employed and having a higher income indeed increase the likelihood of childcare rights knowledge, though these effects are not significant; neither are the effects of length of stay and gender. However, age seems to matter. The older migrants are, the less they know about childcare rights. This might also reflect a weakness of the data which does not contain the specific relationship between respondents and the children living in the household. Older migrants surveyed who live with children might not be the parents but the grandparents or uncles and aunts who are not directly involved in the childcare decisions of the children and therefore less knowledgeable about this process.

Lastly, we see significant differences between migrant groups, confirming the pattern of Fig. 2 to a large extent. Despite controlling for life course-related variables such as age and length of stay, most migrant groups know significantly less about their childcare rights than do migrants from Russia. One plausible explanation for this pattern could be that a significant share of Russian migrants has German roots (so-called Aussiedler) and often has contact with Germany long before migration, which facilitates acquisition of knowledge about childcare rights. Also, migrant groups might differ in their knowledge acquisition depending on their migration motive and country of origin. Migrants might migrate specifically to Germany because of the high-quality and low-cost childcare and therefore put extra effort into obtaining knowledge about their childcare rights. Unfortunately, the data does not provide information on the migration motive. However, we carefully can make the following two assumptions: first, migrants who hold traditional gender role attitudes most likely did not migrate to Germany because of its formal childcare system, as the mother is expected to stay at home to take care of the children. In all models, I control for gender role attitudes; however, no significant effect is observable. Second, because migrants are socialised in very different childcare systems, they have different frames of reference when evaluating formal childcare in Germany and the need to acquire knowledge about childcare rights. Migrants who originate from countries with positive attitudes towards formal childcare might value the high quality and low costs of childcare in Germany, and even migrate for that reason, and therefore have a stronger interest in acquiring knowledge about their childcare rights. Migrants coming from countries where formal childcare is viewed sceptically might have a generally lower interest in formal childcare in the receiving country and therefore put less effort into becoming informed about their childcare rights. To test for such a socialisation effect, I rely on the survey ‘Family and changing gender roles’ from the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP, fourth round, from 2012). Based on the ISSP, I calculated the average support for whether childcare should be formally or informally organised. A value between 0 and 1 was thus given to each person from that country, representing the percentage of the population in the home country that preferred informal over formal care. Unfortunately, the ISSP data misses information for Romania.

Whereas, in China, over 85% of respondents prefer informal over formal childcare, this is only the case for 64% of Spanish people and 55.6% of British people (see Fig. A in the appendix). However, estimating the main models, no home country effect based on childcare attitudes is observable. Although on average migrants who originate from countries with low preference for formal childcare are less likely to possess knowledge about their childcare rights, this effect is not positive. One should bear in mind, though, that these results do not include Romania. The main effects hardly change, with the exception of the effect of social capital, which, once controlled for home country childcare attitudes, is significant at the 10% level (results available on request). Hence, variation in attitudes towards formal childcare seems not to affect migrants’ likelihood of acquiring knowledge about childcare rights in the receiving country.

Conclusion

This paper is one of the first contributions investigating migrants’ knowledge about their childcare rights. Previous research has emphasised that migrants’ lack of knowledge about formal childcare is a crucial barrier to their childcare usage and has negative implications for integration particularly for migrant women and their children (Ballarino and Panichella 2018; Boeckmann et al. 2014; Drange and Telle 2015; Klein and Sonntag 2017). In order to guarantee unbiased and equal childcare to all migrant groups, we need to understand which factors increase migrants’ knowledge and which might work as barriers. I thereby specifically look at migrants’ knowledge about their general entitlements to childcare, or in other words, the legal conditions under which migrants are eligible to access formal childcare to the same extent as natives. If migrants are not aware of their most basic rights, then the chances of their knowing about specific measures such as applying for financial subsidies are even lower.

Using unique data from the project MIFARE, I study nine different migrant groups in Germany. I assume that migrants draw on two main resources in order to acquire knowledge about their childcare rights: human capital and social capital. Migrants are likely to know most about their childcare rights if possessed of good language skills and a high level of education, and if embedded within co-ethnic relations that are likely to provide the information.

In a first step, I investigate the impact of migrants’ human capital in form of language skills and education on their knowledge about childcare rights. Whereas education does not play a significant role, language skills are indeed a driving factor explaining migrants’ childcare knowledge. This indicates that, as is often the case in integration processes, language is key and should be treated as such by policy makers. By now, it is common knowledge that a serious investment in migrants’ language skills is crucial for further integration processes. However, learning a new language is also burdensome and takes time: time that migrant parents, particularly if arrived only recently in Germany, do not have when making important decisions regarding their children’s upbringing. The German government should therefore invest in multi-lingual information programmes educating migrants about their childcare rights, enabling even migrants with little facility in German to inform themselves about their rights and possibilities within the German childcare system. Studies have shown that even mild information intervention in the form of brochures has significant effect in welfare behaviour (Liebman and Luttmer 2015).

However, it is not only the lack of language skills that drives the knowledge gap among migrants. It also matters which contacts migrants have and their chances to acquire childcare-related information via these networks. I argued that migrants benefit particularly from contacts with co-ethnics since they are the most likely to know about migrants’ specific rights in Germany with regard to childcare. This might be particularly true if formal childcare is widely used within the respective ethnic community. Childcare is relevant only for a specific group, namely care-takers of small children, and only migrants who use formal childcare themselves might be aware of their migrant-specific childcare rights and transfer this knowledge to their ethnic peers. The results support this assumption: migrants in Germany who belong to an ethnic group which extensively uses formal childcare (such as Russian or British migrants) do indeed benefit significantly from stronger contact with co-ethnic peers. This study thereby confirms previous qualitative research showing that childcare information is mainly transmitted via co-ethnic migrant communities and that language barriers block the access to knowledge about childcare rights. Federal and communal agencies should therefore be advised in building ‘language-accessible communication strategies […] targeted to migrant communities to increase awareness of (childcare) programmes’ (Karoly et al. 2018. p.92) and their rights within it.

Of course, this study also contains some limitations. Among others, this study does not take into account institutional factors. For example, migrants living in areas with little childcare provision might find it more difficult to acquire respective information than migrants living in areas with a high density of childcare institutions. Also, municipalities with a large share of migrant parents might address the topic of childcare more extensively than municipalities with only very few migrants.

In addition, the MIFARE data only provides information on migrants’ friendship ties, conferring the advantage that potential ethnic-related tensions, which might bias the exchange of information within the network, are unlikely. Certainly relevant as the results show, other networks are likely to affect migrants’ knowledge about formal childcare as well, such as ‘weak ties’ (Granovetter 1973) to colleagues or acquaintances. Moreover, I had to rely on group characteristics on the macro level to assess childcare-related resources within migrant parents’ networks since no information is provided on the actual resources, such as childcare knowledge, that are transmitted within networks. Although the data provide convincing results that childcare-related resources within ethnic groups do affect migrant parents’ knowledge about their childcare rights, we do not know to what extent those resources are embedded within the migrants’ personal networks and whether certain network members are more likely to provide such resources than others (e.g., due to differences in education and length of stay in the receiving country). To assess the mechanisms behind those social influence processes more thoroughly, more data, such as longitudinal ego-centric network data, is needed.

It is also important to note that the measurement of language skills is based on self-assessments and that certain groups tend to over-estimate their language skills (for example, Turkish migrants) whereas others underestimate their language skills (for example, female migrants) (Edele et al. 2015). Although the models control for relevant determinants of over-/underestimation of language skills, such as gender or ethnic background, results might be biased to some extent. Another limitation is the lack of information about the migration motive. It is possible that migrants migrated to Germany specifically because of the childcare which is comparatively low in costs and therefore put extra effort into obtaining knowledge about their childcare rights. Unfortunately, the data does not provide information on the migration motive and future research should consider migrants’ specific interest in this topic based on their migration history.

Despite these limitations, I would like to formulate carefully some policy recommendations. Migrant parents acquire knowledge about their childcare rights most likely either via formal information platforms, such as governmental webpages or formal childcare information brochures, or via informal information networks, such as other migrant parents. If the German government wants to increase migrants’ knowledge about their childcare rights, both channels have to be targeted. I already addressed the need for multi-lingual information programmes educating migrants about their childcare rights. Governmental webpages as well as webpages of local childcare institutions are recommended to distribute their information in multiple languages, depending on the ethnic composition of their neighbourhood. Otherwise, migrant parents with few/inadequate German language skills might not be reached and it is particularly their children who would benefit most from attending formal childcare for their language abilities.

Such information programmes should also take migrants’ social networks into account. Municipalities could include migrant communities, both formal and informal, in their attempt to inform migrant parents about their childcare rights. For example, migrant associations can be asked to distribute relevant information about formal childcare in their communities. An even more specific measure would be the creation of ‘parental buddy programs’, where newly arrived migrant parents are matched with long-established parents who are familiar with Germany’s childcare system, in order to increase migrants’ awareness of their childcare rights. Only if the government guarantees barrier-free access to childcare information, migrant parents are able to make their decision to their best conscience.

Notes

In Berlin and Hamburg, for example, childcare is free for all age groups, in Rhineland-Palatnia only after the age of 2 and, in Bremen, Niedersachen and Hessen after the age of 3 (European Commission 2019)

References

Aguilera, M. B. (2005). The impact of social capital on the earnings of Puerto Rican migrants. The Sociological Quarterly, 46(4), 569–592.

Andreß, H., & Heien, T. (2001). Four worlds of welfare state attitudes? A comparison of Germany, Norway, and the United States. European Sociological Review, 17(4), 337–356.

Ballarino, G., & Panichella, N. (2018). The occupational integration of migrant women in Western European labour markets. Acta Sociologica, 61(2), 126–142.

Barglowski, K., Krzyzowski, L., & Światek, P. (2015). Caregiving in Polish-German transnational social space: circulating narratives and intersecting heterogeneities. Population, Space and Place, 21(3), 257–269. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1904.

Bauernschuster, S., & Schlotter, M. (2015). Public child care and mothers’ labor supply-evidence from two quasi-experiments. Journal of Public Economics, 123, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2014.12.013.

Becker, B. (2007). Bedingungen der Wahl vorschulischer Einrichtungen unter besonderer Berücksichtigung ethnischer Unterschiede (No. 101). Mannheimer Zentrum fuer Europaeische Sozialforschung: Mannheim.

Becker, B. (2010). Wer profitiert mehr vom Kindergarten? KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift Für Soziologie Und Sozialpsychologie, 62(1), 139–163.

Bekhuis, H., Hedegaard, T., Seibel, V., & Degen, D. (2018). MIFARE study-migrants’ welfare state attitudes. Data set. DANS (Data Archiving and Network Services).

Bilecen, B., Gamper, M., & Lubbers, M. J. (2018). The missing link: social network analysis in migration and transnationalism. Social Neworks, 53, 1–3 Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378873317302575.

Boeckmann, I., Misra, J., & Budig, M. J. (2014). Cultural and institutional factors shaping mothers’ employment and working hours in postindustrial countries. Social Forces, 93(4), 1301–1333.

Bucx, F., & de Roos, S. (2015). Opvoeden in niet-westerse migrantengezinnen. Een terugblik en verkenning. Den Haag: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau.

Cantillon, B. (2011). The paradox of the social investment state: growth, employment and poverty in the Lisbon era. Journal of European Social Policy, 21(5), 432–449.

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, 95–120.

Dahl, G. B., Løken, K. V., & Mogstad, M. (2014). Peer effects in program participation. American Economic Review, 104(7), 2049–2074.

De Jong, P. (2019). Between welfare and farewell: the role of welfare systems in intra-European migration decisions. Groningen: University of Groningen.

de Jong, P., & de Valk, H. (2018). Are migration decisions in Europe influenced by social welfare? Demons: Bulleting on Population and Soceity. Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute, 34, 6–7.

Destatis. (2018). Betreuungsquote von Kindern unter 6 Jahren mit und ohne Migrationshintergrund in Kindertagsbetreuung. Retrieved January 30, 2019, from https://www.destatis.de/DE/ZahlenFakten/GesellschaftStaat/Soziales/Sozialleistungen/Kindertagesbetreuung/Tabellen/BetreuungsquoteMigrationU62018.html;jsessionid=751B8F1854AAA9F1E9ABE0344454F6CD.InternetLive1

Drange, N., & Telle, K. (2015). Promoting integration of immigrants: effects of free child care on child enrollment and parental employment. Labour Economics, 34, 26–38.

Edele, A., Seuring, J., Kristen, C., & Stanat, P. (2015). Why bother with testing? The validity of immigrants’ self-assessed language proficiency. Social Science Research, 52, 99–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.12.017.

Esping-Andersen, G. (2002). A child-centred social investment strategy. In G. Esping-Andersen (Ed.), Why we need a new welfare (pp. 26–67). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

European Commission. (2013). Towards social investment for growth and cohesion - including implementing the European Social Fund 201.

European Commission. (2019). Key data on early childhood education and care in Europe.

Faist, T., Bilecen, B., Barglowski, K., & Sienkiewicz, J. J. (2015). Transnational social protection: migrants’ strategies and patterns of inequalities. Population, Space and Place, 21(3), 193–202.

Fawcett, J. T. (1989). Networks, linkages, and migration systems. International Migration Review, 23(3), 671–680. https://doi.org/10.1177/019791838902300314.

Flap, H. (2003). Creation and returns of social capital. In H. Flap & B. Völker (Eds.), Creation and returns of social capital: a new research program (pp. 3–23). New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203643648-11.

Frauke, P., & Spiess, K. (2015). Kinder mit Migrationshintergrun in Kindertageseinrichtungen und Horten: Unterschiede zwischen den Gruppen nicht vernachlaessigen! (1/2 No. 82). Deutsches Institut fuer Wirtschaftsforschung (DIW): Berlin.

Gottfried, M. A., & Kim, H. Y. (2015). Formal versus informal prekindergarten care and school readiness for children in immigrant families: a synthesis review. Educational Research Review, 16, 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.09.002.

Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 347–367.

Griesshaber, N., & Seibel, V. (2015). Over-education among immigrants in Europe: the value of civic involvement. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41(3), 374–398.

Kahn, J. M., & Greenberg, J. P. (2015). Factors predicting early childhood education and care use by immigrant families. Social Science Research, 39(4), 642–651.

Karoly, L. A., Gonzalez, G. C., Karoly, L. A., & Gonzalez, G. C. (2018). Early Care and Education for Children in Immigrant Families, 21(1), 71–101.

Kingston, P., Hubbard, R., Lapp, B., Schroeder, P., & Wilson, J. (2003). Why education matters. Sociology of Education, 7(1), 53–70 Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/3090261.

Klein, O., & Sonntag, N. (2017). Ethnic differences in the effects of institutionalized childcare for children under the age of three. Zeitschrift Fuer Erziehungswissenschaft, 20(1).

Krapf, S. (2014). Who uses public childcare for 2-year-old children? Coherent family policies and usage patterns in Sweden, Finland and Western Germany. International Journal of Social Welfare, 23(1), 25–40.

Lancee, B. (2010). The economic returns of immigrants’ bonding and bridging social capital: the case of the Netherlands. International Migration Review, 44(1), 202–226.

Lastikka, A. L., & Lipponen, L. (2016). Immigrant parents’ perspectives on early childhood education and care practices in the Finnish multicultural context. International Journal of Multicultural Education, 18(3), 75–94.

Liebman, J. B., & Luttmer, E. F. (2015). Would people behave differently if they better understood social security? Evidence from a field experiment. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 7(1), 275–299.

Magnuson, K., & Madison, W. (2006). Preschool and school readiness of children of immigrants n. Social Science Quarterly, 87(5), 1241–1262.

Mamolo, M., Coppola, L., & Cesare, M. D. (2011). Formal childcare use and household socio-economic profile in France, Italy, Spain, and UK. Population Review, 50(1), 170–194.

Massey, D. S., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A., Pellegrino, A., & Taylor, J. E. (1993). Theories of international migration: a review and appraisal. Population and Development Review, 19(3), 431–466 Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/2938462.

Miller, P., Votruba-drzal, E., Levine, R., & Koury, A. S. (2014). Immigrant families ’ use of early childcare : predictors of care type. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(4), 484–498.

Mohr, K. (2005). Stratified rights and social exclusion of migrants in the welfare state. Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 34(5), 383–398.

Morris, L. (2002). Managing migration: civic stratification and migrants rights. London: Routledge.

Morrissey, T. W. (2017). Child care and parent labor force participation: a review of the research literature. Review of Economics of the Household, 15(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-016-9331-3.

OECD/Eurostat/UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2015). ISCED 2011 Operational manual: guidelines for classifying national education programmes and related qualifications. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264228368-en.

OECD. (2016a). Early childhood education and care. Data Country Note - Germany. Starting Strong, IV, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

OECD. (2016b). Who uses childcare: background brief on inequalities in childcare use.

OECD. (2017). A portrait of family migration in OECD countries. In International Migration Outlook 2017 (pp. 107–166).

Peisner‐Feinberg, E. S., Burchinal, M. R., Clifford, R. M., Culkin, M. L., Howes, C., Kagan, S. L., & Yazejian, N. (2001). The relation of preschool childcare quality to children’s cognitive and social developmental trajectories through second grade. Child development, 72(5), 1534–1553.

Pfau-Effinger, B. (2005). Culture and welfare state policies: Reflections on a complex interrelation. Journal of social policy, 34(1), 3–20.

Pfau-Effinger, B. (2012). Women’s employment in the institutional and cultural context. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 32(9/10), 530–543.

Portes, A., & Sensenbrenner, J. (1993). Embeddedness and immigration: notes on the social determinants of economic action. American Journal of Sociology, 98(6), 1320–1350.

Renema, J. A. J. (2018). Immigrants’ support for welfare spending: The causes and consequences of welfare usage and welfare knowledgeability (ICS dissertation series). Nijmegen: Radboud University Nijmegen.

Roßbach, H.-G., Kluczniok, K., & Kuger, S. (2009). Auswirkungen eines Kindergartenbesuchs auf den kognitiv-leistungsbezogenen Entwicklungsstand von Kindern. In Frühpädagogische Förderung in Institutionen (pp. 139–158). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Ryan, L., Sales, R., Tilki, M., Siara, B., & Sales, R. (2008). Social networks, social support and social capital: the experiences of recent Polish migrants in London. Sociology, 42(4), 672–690.

Schnelle, R.-D. (2013). Hurdle race to childcare: Why parents with a migration background send their child less often to early childhood day care. Expert Council of German Foundations on Integration and Migration, Policy Brief.

Schober, P. S., & Spiess, C. K. (2015). Local day care quality and maternal employment: evidence from East and West Germany. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77(3), 712–729. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12180.

Scholz, A., Erhard, K., Hahn, S., & Harring, D. (2019). Inequalities in access to early childhood education and care in Germany. International Centre Early Childhood Education and Care, Working Paper, 2.

Seibel, V. (2019). Determinants of migrants’ knowledge about their healthcare rights. Health Sociology Review, 28(2), 140–161.

Seibel, V., & Hedegaard, T. (2017). Migrants ’ and natives ’ attitudes to formal childcare in the Netherlands , Denmark and Germany. Children and Youth Services Review, 78, 112–121.

Seyda, S. (2009). Early childhood education and later educational attainment-an analysis with the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) (Kindergartenbesuch und späterer Bildungserfolg Eine bildungsökonomische Analyse anhand des Sozio-ökonomischen Panels). Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 12(2), 233–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-009-0073-3.

Söhn, J. (2013). Unequal welcome and unequal life chances: how the state shapes integration opportunities of immigrants. European Journal of Sociology, 54(2), 295–326.

Van Gameren, E. (2013). The role of economic incentives and attitudes in participation and childcare decisions. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 34(3), 296–313.

van Oorschot, W. (2006). Making the difference in social Europe: deservingness perceptions among citizens of European welfare states. Journal of European Social Policy, 16(1), 23–42.

Vesely, C. K. (2013). Early childhood research quarterly low-income African and Latina immigrant mothers ’ selection of early childhood care and education ( ECCE ): considering the complexity of cultural and structural influences. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(3), 470–486.

Waldfogel, J. (2006). What do children need? Public Policy Research, 13(1), 26–34.

Zoch, G., & Hondralis, I. (2017). The expansion of low-cost, state-subsidized childcare availability and mothers’ return-to-work behaviour in East and West Germany. European Sociological Review, 33(5), 693–707. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcx068.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Seibel, V. What Do Migrants Know About Their Childcare Rights? A First Exploration in West Germany. Int. Migration & Integration 22, 1181–1202 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-020-00791-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-020-00791-0