Abstract

The sub-Saharan cities are growing and changing due to immigration and modernization. One of the consequences of the current urbanization is that an increasing number of families residing in peri-urban areas of small rural towns lack access to basic municipal and ecosystem services. The purpose of the paper is to demonstrate the impacts of peri-urban expansion on municipal services provided by the governments and on ecosystems services through a case study of a small rural town called Makhado Biaba in Limpopo Province of South Africa. Makhado Biaba has been experiencing incessant rapid physical expansion over the years. Such spatial expansion into the peri-urban zone impacts the provision of municipal services such as water, electricity, sewerage, and refuse collection. In 2020, an exploratory mixed-methods study of some anthropocentric and ecosystem changes in Makhado Biaba Local Municipality in northeast South Africa was executed. Land use was mapped for the time period of 1990–2020, data were gathered through a household questionnaire in six villages, and interviews were held with municipal officials. Among others, the study showed that several municipal services are available in the peri-urban villages of Makhado Biaba Town despite the distant locations outside the urban core. However, services are not uniformly distributed due to that new peri-urban developments that are leapfrogging into vacant land without supporting infrastructure. The pace of the municipality in providing the necessary municipal services such as water and energy supply, as well as sanitation and refuse removal, is lagging behind the development of new and unplanned housing areas. The findings bring about information about the suburban livelihoods and how the administration of the peri-urban areas can respond to the needs of the inhabitants as well as to future challenges. For instance, to facilitate local development, recurrent and well-structured citizen dialogs with local groups to identify delivery failures are strongly recommended. In addition, the impact on ecosystem services by the city development and land use change stresses the need for guided urban development and expansion and also settlement upgrading programs in peri-urban zones to limit the bad effect on ecosystem services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Urbanization is a global trend which is likely to continue for some decades and leads to changes in life in cities such as livelihood and land use changes, as well as the socio-ecological relations (Hungwe, 2014). In the sub-Saharan region, cities are growing and changing because of the twin forces of urbanization and migration. In today’s South Africa, the shortage of housing due to incessant urbanization is one the most topical and debated issues. The South African government offers social housing, but the process of allocating these houses to beneficiaries is often long and bureaucratic. Ostensibly and increasingly, urbanization processes have been supported by the access to economic opportunities and access to urban infrastructures and services Zhang, 2016. It highlights issues related to life in cities: livelihood and land use changes, as well as the socio-ecological relations. In today’s South Africa, the shortage of housing is one the most topical and debated issues. In the sub-Saharan region, cities are growing and changing because of immigration and modernization. The government offer social housings, but it is a long and often bureaucratic process to receive such a house. There are opportunities for people to get social housing from the government through the Reconstruction and Development Program (RDP). This program is a South African social housing scheme that is subsidized by the government to provide housing to the urban poor. Furthermore, a growing number of families lack access to basic municipal services (Darkey & Visagie, 2013). Access to quality services in newer suburban spaces remains a critical planning function for municipalities, in need of implementation to be accessible for all citizens. The services are understood as a prerequisite for local prosperity and to increase the well-being and life expectancy, as well as for future developments outside of bigger cities. The global call of our time states the critical role of cities to provide socially, economically, and environmentally sustainable conditions for all, including access to services in peri-urban areas (Allen, 2003, 2010; Chanza & Musakwa, 2021; Wandl & Magoni, 2017).

Nevertheless, many families in developing countries, particularly in the sub-Saharan African region, lack access to basic municipal services such as water, housing, sanitation, and electricity (Ingwani & Gumbo, 2016). Similarly, in South Africa, municipal service provision for water, sanitation, transportation, electricity, primary health care, education, housing, and security to all residents and within a safe and healthy environment is increasingly becoming a burden for most local municipalities (Community Survey Report, 2016). Thus, the situation for families residing in the outskirt’s areas of small rural towns away from service infrastructure and other opportunities is further aggravated. However, housing backlogs continue to increase as was under apartheid, and during the post-apartheid period (Reddy, 2016) and continual migration of people into zones located in the urban periphery. Thus, population increase in the peri-urban and informal villages in rural parts of the country is putting a pressure on existing municipal services. In turn, they fail to meet the demands of a growing number of residents (Musakwa et al., 2020).

This study shows the importance of integrating social and ecological perspective toward an establishment of an ecosystem services governance that will enhance human well-being in urban areas. The links between the social and the ecological system may include knowledge held by traditional authorities, municipal communities, and or scientific knowledge held and used by government resource managers. The social-ecological system approach considers institutions and governance as an integral part of the ecosystem, not separate from it (Haase et al., 2014). Berkes (2017) pointed out that systems of people and environment need to be considered together and not separately. A sustainable community-governance nexus must be built on the collaboration between a diverse set of stakeholders like the two systems (state and indigenous) in the present study. A governance approach where a social-ecological coproduction of ecosystem services will occur between the two systems will offer a new understanding of the synergies between the socio-ecological, the socio-economic, and ecologic-economic perspectives. Besides, the city growth has detrimental consequences on the ecosystem services since the non-planned growth brings different ecological and environmental problems such as water and air pollution (Kremen, 2005) to be handled by the municipality.

Background

In South Africa, rural towns were established as a tool to bring services and generate development in smaller communities, particularly in the former homelands (Nel & Rogerson, 2007; Tsoriyo et al., 2021). The economy of smaller towns is dependent on agriculture, mining, tourism, and business enterprises dotted around an urban core. While small towns emerge as growth nuclei in marginalized rural communities, there are discrepancies in terms of the quality of the provision of, as well as the quality of the municipal services (Moffat et al., 2021; Nel & Rogerson, 2007). Urban centers of South Africa are classified as “towns” and “cities, and these are further disaggregated as metropolitan agglomerations, secondary cities, small towns, and small rural towns” (Moffat et al., 2021; Tsoriyo et al., 2021). The situation is even more apparent in the peri-urban villages surrounding the small rural towns whose boundaries are continuously shifting outwards. The National Development Plan Vision 2030 of South Africa was promulgated to eradicate such discrepancies and to make services accessible to all citizens in the republic (Musakwa et al., 2013).

Peri-urban areas are per se located in the outskirts but the notions of peri-urban and peri-urbanization are not well-defined. They often refer to a compound of rural and urban features in transition which are characterized by unregulated land uses and multiple land administration structures (Hungwe, 2014; Ingwani, 2021) without a fixed definition. Additional to the conventional rural and urban spaces, the peri-urban areas may be conceptualized as a “third space” (Ingwani & Gumbo, 2016). However, due to the plurality of activities, people, and land uses found in peri-urban areas and outside the homes and workspaces, the definitions of peri-urban zones need to capture the contextual dynamics, including socio-political and cultural aspects such as formal or informal forms of governance. Currently, given the local circumstances and pressure for land and housing, peri-urban areas emerge as a key urban and regional planning research concern when it comes to the use of resources and their sustainability (Birkmann et al., 2010; Mngumi, 2020; Musakwa et al., 2020). These concerns, the municipal and ecosystem services, were investigated in Makhado Biaba Town, situated in the northern tip of the Limpopo Province of South Africa from the perspective of an outward process of urbanization.

The Presentation of Makhado Biaba Town and Its Villages

The small rural Makhado Biaba Town with almost 6000 residents consist of nine villages, and six villages were selected purposively and conveniently to participate in the research (Makhado IDP, 2018/19). In terms of land administration, the peri-urban villages of Makhado Biaba Town are administered by local traditional leadership, chiefs, and village heads. They serve as the basic structure in land administration, particularly for distribution of land tenure rights on behalf of the state and the local municipal authorities (Ingwani, 2021). As such, traditional leaders are responsible for the distribution of land use and other property rights through land transactions which take place in the peri-urban villages. The villages are administered by a municipality Category B called Makhado Local Municipality at an office in Louis Trichardt, 51 kilometers from Makhado Biaba Town. According to Dubazane and Nel (2016), the traditional leadership is “an institution that includes political, socio-political and politico-religious structures which are rooted in the pre-colonial rather than in the formations of colonial and post-colonial states.” This also implies an alternative and local understanding of the meaning of land, “[h]owever, indigenous concepts of land differ and, subsequently, so do the approaches to land use management” Op cit, 2016: 222.

The parallel systems act within their own formal space, and the communications between the double system are poor (Dubazane & Nel, 2016). The result is a power struggle between the local traditional leaders and the local municipality with regard to land administration and control over the activities in the villages surrounding Makhado Biaba Town. They host a more diverse population in terms of place of origin, language, and cultures than the town itself. This diversity not only points to the cosmopolitan nature of the challenges and opportunities experienced in the peri-urban villages but it also depicts peri-urban zones as hubs of hybrid of activities, people, and processes. It also means that the core city area is dominated by state (municipal government and policies), whereas the villages are run by the so-called customary law, to a large extent.

The research findings revealed that the dominant land uses in the peri-urban villages of Makhado Biaba Town are agricultural and residential, while the institutional land use is the least common. Field research data also shows that in 2020, only 22% of the residents were formally employed, while 34% were unemployed and 21% were retired pensioners. The rest of the community residents survived on government grants, agriculture production, and informal activities such as petty trading. Unemployment has been a cause for concern in most small rural towns of South Africa (Community Survey Report, 2016). Most of the economically actives with formal employments earned R3500 (Values in South African Rand, 100 Rand for 5.48 American Dollar, 25 October 2022) or less, per month. The others survived on government grants, agriculture production, and informal activities such as petty trading.

Urban boundaries separate the urban land from the rural villages. However, boundaries mark where occupied spaces begin and end, without necessarily confining activities and people Ingwani, 2019. Peri-urban expansion and the occupation of land means that new and peri-urban zones without existing municipal services or formal planning are created. The formal town boundaries are shifting leaving many households without access to basic municipal services such as water, sanitation, housing, roads, and electricity. Thus, the ongoing urbanization shows the porous character of informal developments and governing practices in flux. Besides, the city growth has detrimental consequences on the ecosystem services since the non-planned growth brings different ecological and environmental problems such as water and air pollution (Kremen, 2005) to be handled by the municipality.

In sub-Saharan Africa, knowledge and policies regarding the peri-urban municipal service deliveries and ecosystem services are largely missing. The knowledge gaps stem from inadequate conceptualization and lack of understanding the need for such information to support the development of sustainable cities for all, as recommended in the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11 (United Nations, 2015). Knowledge regarding local conditions and needs will have to be translated into policy, planning, and management imperatives. Municipal and ecosystem services will have to be explicitly and systematically integrated into decision making by individuals, corporations, and governments (Daily et al., 2009). In contrast to the planning of municipal services, knowledge regarding the value of ecosystem services in peri-urban areas is missing out worldwide (Mngumi, 2020). Hence, to increase sustainability informed policies to be translated into plans and their local implementation is a prerequisite. Currently, the peri-urban expansion of Makhado Biaba Town seems to be inevitable. Furthermore, peri-urban expansion is likely to continue for as long as the agricultural land is available in the vicinity. In many small rural towns of South Africa, agricultural activities are slowly diminishing because of the insurgence of a cash economy and off-farm income streams. According to Ingwani (2019), similar situations were observed in Domboshava and Masvingo in Zimbabwe, where peri-urban livelihoods are changing because of the outward spatial expansion of the peri-urban zone.

The peri-urban expansion of Makhado Biaba Town is thus attributed to increased land transactions catalyzed by the traditional leaders. Consequently, they engender the development of new residential areas in the urban periphery. But, parallel to older structure of land tenure administration is the responsible national authority and its local municipality, creating a conflict. In most cases, chiefs argue and push for the preservation of cultural values and control of land in their jurisdiction (Hungwe, 2014; Ingwani & Gumbo, 2016). Politicians are preoccupied since the extensions mean that the areas of influence increase at pace with a growing number of electoral supporters. However, environmentalists and municipal spatial planners are more worried about the environmental implications of peri-urban expansion (Ingwani & Gumbo, 2016). In South Africa, the local municipalities are responsible for land use planning and spatial planning functions in the peri-urban villages as well as for providing services and infrastructure in the areas (Ingwani, 2019; Moffat et al., 2021). Under such circumstances, residents of peri-urban villages tend to align with their traditional leaders over issues related to land tenure and land property rights and then associate with the local municipality for provision and access to services and infrastructure.

The Aim of the Study and the Research Design and Methods

The purpose is to highlight the impact of the increased peri-urban expansion of the small rural town of Makhado Biaba into adjacent villages. First, the objective is to study the municipal and ecosystem services available in Makhado Biaba Town; second, to inquire the municipal challenges and opportunities associated with the provision of services; and third, to recommend strategies for improved service provision in the urban periphery (anthropocentric and ecological changes). The Makhado Biaba Town and its surrounding villages were purposively selected for a study by virtue of their location, the peri-urban characteristics, and the complex governmental issues.

Literature Review

The section presents related literature on key concepts such as peri-urban expansion, municipal services, ecosystem services, infrastructure provision, and small rural towns. It also provides a general review of policies and legislation related to spatial planning practice and service provision in South Africa. Finally, a couple of some methods such as the nature-based theories are presented as well.

Peri-Urban Expansion

It is an urban process that results from human activities which extend and spill over into the urban periphery of the city boundaries (Duvernoy et al., 2018; Ingwani & Gumbo, 2016; Salem, 2015; Wandl & Magoni, 2017). Suburbanization is an old and global issue identified by Swyngedouw and Kaika (2014), among others. According to Swyngedouw and Kaika (2014:462), “the urbanization of nature, i.e., the process through which all types of nature are socially mobilized, economically incorporated (commodified), and physically metabolized/transformed in order to support the urbanization process.” As the peri-urban zones extend into the hinterland, the existing peri-urban zone is pushed out further and replaced by a new frontier usually characterized by inhabited land. Thus, through such expansion, rural areas assume the character of cities. In most cases, peri-urban expansion is accompanied by changes in social, economic, and political environments, as well as changes in land uses (Musakwa & Wang, 2018).

The same process was framed as the “continuous city” sprawling over an ever-warming planet (Tzaninis et al., 2021). A city without end is contributing to alternative understandings of city developments. Such cities will not develop in the same way as the European cities, and thus, other notions and theoretical tools to study and analyze city growth are brought along.

Municipal Services and Infrastructure Provisioning

Municipal services comprise an array of amenities provided to citizens residing in municipalities, such as water, electricity, housing, health, education, and waste management. Furthermore, modern infrastructure and facilities critical for the wellbeing of people living in any community are required to increase sustainability. Provisioning of municipal services to people is a constitutional obligation by law, and it cannot compromise the minimum basic standards (Batley, 1996). However, there is a growing consensus in the literature that quantity and quality of ecosystem and municipal services are deteriorating in urban and peri-urban areas and particularly those in sub-Saharan Africa (Roy et al., 2017).

Lack of modern infrastructures challenge provision of basic services, which in turn have a negative impact of the residents. At the municipality level, the quality-of-service deliveries are decided on. As such, new residential developments located in the urban periphery increase the demand for more municipal services, thus creating pressure on existing amenities. Most municipalities struggle to extend the basic services to people. They often priorities the affordability, accountability, and competitiveness within the municipal demarcated development zones (Moffat et al., 2021). The rapid increase of peri-urban areas without defined spatial planning pattern makes it difficult for the regional governments and municipalities to provide services in these additional spaces. Whenever rapid urbanization occurs, it also becomes more difficult to handle ecosystems degradation and loss of ecosystem services in peri-urban zones (Niemelä et al., 2010).

Ecosystem Services

The concept of ecosystem services, which encompasses the human benefits derived from ecosystem functions generated by nature and ecosystems, is applied in urban planning to manage and sustain biodiversity and ecosystem services (Costanza et al., 2021). The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA, 2005) point out the importance that the variety of ecosystems provide a range of services that are of fundamental value to human well-being, health, livelihoods, and survival (MEA, 2005). According to MEA (2005), the ecosystem services are divided into (a) the supporting, (b) provisioning, (c) regulating, and (d) cultural categories. The boundaries between different ecosystems are not always clear, such as when agricultural and forest lands are near, or penetrate urban environments. Cities are sometimes seen as a single ecosystem, but they should rather be seen as a variety of multiple ecosystems, including for example: lakes, ponds, meadows, beaches, and parks (Niemelä et al., 2010).

Urbanization poses major challenges in preserving ecosystem services that could be a visible contribution for the role of green infrastructure and improving the physical planning of cities and small towns. In urban areas, the creation of ecosystem services is crucial to the conservation of biodiversity. The ecosystem services include air purification, water and climate regulation, storage of coal, and regulation of stormwater are of great importance. The ecosystem service concept can today be perceived as a promising strategy for decision-making authorities when planning urban environments in favor of healthy living conditions and when increasing quality of life (Sen & Guchhait, 2021).

Small Rural Towns

Urban centers of South Africa are classified as “towns” and “cities are disaggregated as metropolitan agglomerations, secondary cities, small towns, and small rural towns” (Moffat et al., 2021; Tsoriyo et al., 2021). As such, small rural towns of South Africa are service centers located in the rural areas on the bottom rung of the ladder that classifies and defines cities. They are surrounded by villages dominated by agricultural production. Furthermore, towns are largely administered by a dual system of land administration comprising the traditional leadership and local municipalities (Antrop, 2004). The peripheries of small rural towns are thus blurred by a lack of formal and planned residential developments. Currently, a significant number of South Africa’s population live in small rural towns which experience considerable inflow of migrants.

In South Africa, the migration pattern often involves migrants making a first stay in peri-urban villages of towns located close to their port of entry such as Makhado Biaba Town, before continuing to their preferred destiny, Johannesburg, Cape Town, or Durban (Hungwe, 2014). Minor towns play an important role in providing services to migrants looking for work and a place to stay, although such “third places” are deeply neglected with regard to service provision, particularly in the hinterland. Yet, all citizens have the right to access adequate services regardless of where they are from, or their social status (Harvey, 2003).

Related Policies and Legislations on Municipal Service Provision

In South Africa, state policies and laws are used to ensure service provision in small rural towns. The policies are applied uniformly in urban and peri-urban zones and include SDGs, the Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act 16 of 2013, and the Municipal Systems Act 32 of 2002. The spatial planning tools are critical enablers to municipal services in both urban and peri-urban zones. For example, SDG 11 aims at building sustainable cities and communities and guide local municipalities to draft strategies which direct spatial planning functions and growth of towns toward inclusive and resilient human settlements (Klopp & Petretta, 2017).

The National Development Plan of South Africa (2013) was designed to transform human settlements into livable spaces with basic services. Furthermore, the Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act 16 of 2013 provides a uniform, effective, and comprehensive system of spatial planning and land use management for the Republic of South Africa. The Act has five principles: spatial resilience, spatial justice, good administration, spatial sustainability, and efficiency. It prioritizes social inclusiveness and integration of previously disadvantaged areas into the municipal planning imperatives. The Municipal Systems Act 32 from 2000 is a framework which defines municipal functions and powers, as well as principles and methods critical to provisioning of accessible and affordable services for all citizens. In this way, the Act empowers local municipalities to fulfill their constitutional mandate regarding service delivery in their areas of administration. While the regulatory and policy procedures are clear about the rights to services for all citizens, a growing number of families living in the peripheries of cities in South Africa and sub-Saharan Africa lack basic municipal services.

Nature-Based Thinking

In the Nordic cities, the management of open spaces in cities is approached in what is called the nature-based thinking (Randrup et al., 2020). The intention is to overcome the division of nature and culture and to go beyond the anthropocentric and modernistic development and bring back the importance of nature into the development of cities as well. The comprehensive idea focusses on three fundamental relations: the socio-ecological, the socio-economic, and ecologic-economic relations. In other words, nature-based thinking targets what constitute man in the natural and built environment and how sustainable cities can be achieved. See below the theoretical framework.

The approaches to human-ecological relations are discussed with the intention to inspire and provide tools for policy and planning beginning with ecosystem services as an outset for the development of inclusive cities. One of them is the nature-based thinking drawing attention to people living of, and in, the natural environment and away from the view of nature as only for people with the intention to generate the needed knowledge to establish sustainable and inclusive cities, see Fig. 1. It requires a focus on at least three fundamental relations: (1) Community-Governance nexus, (2) Community-Ecological nexus, and (3) Ecological-Governance nexus. Additionally, the interlinkages between the three kinds of relations require attention and research to develop relevant policies (Randrup et al., 2020).

The three interrelations in nature-based thinking. Source: Randrup et al. (2020)

The Research Group, Methods, and Theoretical Framework

The Research Group

The research is part of an international partnerships and a collaboration between six universities from South Africa and Sweden under the South Africa - Sweden University Forum (SASUF). In South Africa, the universities the University of Venda, University of Johannesburg, and Free State University are participating. The Swedish collaborating universities are Malmö and Gothenburg. The research members represent several different disciplines and methods, such as Urban and Regional Planning, Plant Physiology, Development Research, and Geography. To study peri-urban areas, strike a balance when researching urban complexity and to enable a more prominent role for ecosystem services in peri-urban areas, and two main strands of research were chosen: the anthropocentric and ecological aspects. By means of the abovementioned nature-based thinking and the multi-disciplinary research group, empirical information about both urban and rural issues were gathered. The integration of different findings will contribute to the transition toward sustainable cities in line with SDG 11.

The Research Design and Methods

To answer the aim regarding the peri-urban expansion impact on various kinds of services, the research was designed to produce a brief outlook and an overall picture of two main issues: the anthropocentric or the socio-political and the environmental challenges by means of a case study approach. Makhado Biaba Town and its six peri-urban villages in the Vhembe District in the northern Limpopo Province of South Africa were selected due to its unique peri-urban and small rural town features and location. Although almost all small rural towns in South Africa are undergoing evident peri-urban expansions, the Makhado Biaba town provided an opportunity to demonstrate the impact of such developments on municipal services due to the incessant encroaching of urban forms of development that are self-driven by the residents on the rural vicinities. The research was carried out in the peri-urban villages of Makhado Biaba Town, approximately 156 km from the provincial capital of Polokwane (Fig. 2). The presence of vast tracts of agricultural land in the peri-urban areas of Makhado Biaba Town is a key driver of the shifts of the urban boundary into the town’s peri-urban zone. The villages in the peri-urban zone are regarded as rural until they are proclaimed urban. Makhado Biaba Town falls within the greater Savannah Biome, commonly known as the Bushveld with some small pockets of grasslands and forests (Makhado IDP, 2018/19). These and other factors have produced a unique assortment of ecological niches and ecosystems, which are in turn occupied by a wide variety of plants. The soil in the surroundings of Makhado Biaba Town is fertile; hence, rich for production of crops (including maize); fruits such as mango, berries, and oranges; and vegetables (spinach and delele). Makhado Biaba is generally rocky and can be described as a mountainous area in local terms (Phaswana, 2020).

The geographical aspect of land use change over time was mapped and quantified for the study area and its surroundings in a Geographic Information System (GIS). The South African National Land Cover (SANLC) data sets for 1990, 2014, and 2020 were downloaded for the entire Limpopo Province at the home page of the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and Environment (DFFE) Department of Forestry, Fisheries & the Environment (2022). The large number of 72 land use classes available in original data were grouped into eight classes: forest land, shrubland, grassland, waterbodies, wetlands, barren, cultivated land, and built-up land. One map for each year was produced for the study area and its surroundings to show the spatial distribution of these eight land use classes. To complement the maps, land use areas in hectares were calculated for each year. To help identify the most pronounced changes from one specific land use to another, a categorical change detection analysis was made for 1990 to 2020. In addition, land use areas in square kilometers were calculated for each year for the entire Limpopo Province. The Limpopo Province land use areas provide reliable information on overall land use change in comparison to the small study area and its surroundings. The land use change information is crucial for understanding the development of the ecosystem services of critical importance for the local communities. In 2020, an exploratory case study was developed focusing on the social and ecological aspects described by Yin (2014) as suitable for explaining phenomena in terms of how, where, what, and why “things” happen the way they do. A mix of integrated qualitative and quantitative methods was applied in the collection and analyses of data (Vaismoradi et al., 2016). An approach to spatial planning assumes an eccentric and informal model of Occupy-Build-Plan-Service Model as opposed to the formal and traditional model of Planning-Servicing-Building-Occupying (Sliuzas et al., 2010:69; Gumbo, 2014; Gumbo, 2015). The Planning-Servicing-Building-Occupying model follows the municipal planning processes in housing and municipal services provision. The Occupy-Build-Plan-Service Model is defined by land invasions and unsanctioned housing developments ahead of provisioning of housing and municipal services (Sliuzas et al., 2010). The field work was carried out by Master Students from the South African universities.

Interviews were conducted with municipal officials from Makhado Local Municipality. In addition, interviews with the representative people living in the area. The students gathered and documented first-hand information on the impact of peri-urban expansion on municipal services provision in Makhado Biaba Town. The households in the peri-urban villages of Makhado Biaba Town were targeted because they have experienced both peri-urban expansion and inadequate basic municipal service delivery. A total of 91 residential units from 6 villages were selected, and the household questionnaires were distributed as follows Tshirolwe Ext2 (9), Mabirimisa (11), Tshithunitshanntha (26), Tshirolwe (15), Tshithuni (15), and Mapakhopele (15), see Fig. 2. The residential units did not necessarily represent single households or families, as some people shared space as lodgers. In other words, data was collected from the targeted residential units through a household questionnaire consisting of closed and open-ended questions. To save time and to achieve a high response rate, the questionnaires were self-administered.

Additionally, interviews were carried out in their homes in the peri-urban areas. By means of home visits, the students could observe and document the residential standard. The interviews were semi-structured, containing both open and closed questions. In addition, open-ended interviews were conducted with municipal officials from Makhado Local Municipality, so-called key informants. They contributed with valuable information on the current state of service delivery in Makhado Biaba Town and its peri-urban areas. The social science research design offered exceptional research opportunities that facilitated unraveling the complexities that define peri-urban expansion in small rural towns. This approach also made it possible to navigate the sustainability challenges.

Theoretical Framework

The local findings will be discussed in different ways with the intention to make a “transformative turn” (Randrup et al., 2020: 921), a further development of existing anthropocentric and solutions-based approaches such as the SDG11. The rapid spatial growth of Makhado Biaba Town has led to changes in land use and increased pressure on common natural resources. A change in land use could be to establish a temporary business or make room for a minor house in so-called open, or non-occupied space in a park, next to a river, or on a footpath. The production of space brings about new opportunities for families with reduced resources and hence, findings are discussed from the point of view of anthropocentric development of settlements and the development of ecosystem services. The SDG 11 recommends that settlements shall integrate the development of natural resources in combination with human developments equally, to become more sustainable. Nature-based thinking takes a step further and stresses the core topics that constitute man in the natural and built environment to increase the role of nature in cities (Randrup et al., 2020). “Thus, ecology becomes a frame and a basis for decision making in relation to, for example, resilience in order to prioritize sufficient room for urban nature, and to allow more resource efficient, naturalistic and non-technological growing conditions” (Randrup et al., 2020: 923). They also put forward three basic relations to disentangle the complexity at stake: the socio-ecological, the socio-economic, and ecologic-economic relations. The approach using three basic relations are used in the findings which are divided into different sections as (A) community, governance, and planning; (B) economic and social aspects; and (C) ecosystem services. Taken together, the three notions explain the notion of nature-based thinking by means of three relations:

-

1.

By revisiting the ecological dimension, we can create more room for nature also beyond human services and solutions, and especially in the urban areas, to build in more space for natural processes, ecosystem functioning, and long-term unpredictability

-

2.

By revisiting the community dimension, we can create a new urban esthetic, in which experiences with a diversity of natural elements may allow for more diversity in what nature (should) look like, rather than the opposite (because of limiting growing conditions, or limitations set by the economic system), and

-

3.

By revisiting the economic dimension and closely linked political and organizational perspectives of nature in cities, including new governance structures, we may recognize the need to break siloes and build opportunities associated with linking formal government with local communities (Randrup et al., 2020: 923)

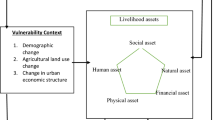

The socio-political context in the peri-urban spaces in South Africa is somewhat homogenous, and the study aims at gathering information about selected family’s ways of life (rural or urban) and facilitate the analyses. According to Carney (1998), there are five categories of livelihoods assets referring to the resource base of a community: human, natural, financial, physical, and social capital. The assets are interlinked, and these forms of capital vary between communities and households. The various categories of households or families access the resources in different ways, and the framework is useful when pinpointing the socio-economic profile of each of the groups in peri-urban locations. Key issues and contradictions, as well as pointing toward areas where actions may proceed, and common goals can be achieved when it is combined with the integrative analysis derived from the participatory field work (Scoones, 1998).

The “principal-agent framework” presents a triad of relationships “between” the state as the principal service provider, the local municipalities as the state agents in service provision, and the local communities as the service recipients. Accountability of the principal and agents to the communities is an important enabler in the service delivery triad. The framework assists to reveal the extent to which the people are involved in planning and influencing the development of their spaces to generate meanings from data to understand the impact of municipal services delivery in the peri-urban villages of Makhado Biaba Town. The discussion also draws from the perspective of Harvey’s (2003) right to the city concept when describing not only the right of access to existing resources, as well as a right to change and to challenge unfavorable conditions. It entails the right to a remake by creating a qualitatively different kind of urban sociality and better conditions in cities.

Field Work Findings

The section presents the findings from the survey in the villages of Makhado Biaba Town in 2019. To facilitate the discussion, findings are grouped under different subtitles: (A) community, governance, and planning; (B) economic and social aspects; and (C) ecosystem services.

A. Community, Governance, and Planning

The peri-urban areas offer the residents attractive possibilities to enjoy a rural lifestyle while living within a semi-urban context. The sampled residents of peri-urban of Makhado Biaba Town enjoy benefits such as availability of cheaper land for housing and access to an urban lifestyle due to proximity to the town. For example, some residents built modern houses which are indicative of luxurious lifestyles. In doing, the peri-urban dwellers continue being in touch with their cultural roots, while adapting to the change of times and embracing an attractive and modern lifestyle (Hungwe, 2014). The fragmented or uneven service distribution is a critical pointer to the adequacy and inadequacy of basic municipal services in the peri-urban villages.

During the survey, it was found that disparities in municipal service provision are largely a result of shifts in the urban boundary, where new peri-urban development is leapfrogging into vacant land without infrastructure services and into spaces where the municipal pace of provisioning is lagging. The most neglected categories of municipal services are waste management, water, storm water drainage, and sanitation (Fig. 3). According to the study, the following are also the most important services.

A. Electricity

There are power lines of electricity in all villages except in the new residential zones. Most of the sampled households (84%) have access to electricity because municipalities are mandated to provide electricity in any human settlement that is more than 24 hours old. As such, municipal provision of electricity in the peri-urban villages of Makhado Biaba Town is the most common and accessible service. Community residents pay for electricity, but in some cases, family’s resort to illegal connections to avoid buying electricity and these actions come with negative implications for the national power grid. The residential units in the peri-urban villages of Makhado Biaba Town are yet to receive electricity services resort to wood fuel for heating and cooking. For families, this is an affordable alternative compared to buying electricity, gas, and paraffin.

A. Sanitation

During the survey, it was found that the peri-urban villages lack sanitation services. Toilet and sewer facilities have become the responsibility of individual households. Families with flush toilets use septic tanks as sewer collection facilities. Residents without access to flush toilets build home-made toilets made of steel sheets or bricks, since there are no alternatives available in the peri-urban spaces. The formal argument from the interviews is that there are no municipal funds to pay for toilets and that the families are not paying municipal taxes.

A. Conflict in Land Administration and Spatial Planning Imperatives

The interviews with municipal officials revealed that the South African government has a huge housing backlog, and it is thus battling to meet the increasing demand for housings by the citizens. However, the dual and parallel administration structure applied in the peri-urban villages present a struggle for the control of land and other natural resources among the traditional chiefs, municipality authorities, politicians, residents, and environmentalists.

The residents of the peri-urban areas of Makhado Biaba Town expect to receive services from the municipality, and the local municipality is accountable to residents because it is their mandate to ensure adequate service provision. It is always anxious about service delivery backlogs. At the heart of such conflicts lies the needs and rights of residents to access the municipal services.

Furthermore, there is no accountability between the municipality and the traditional authorities which are the key stakeholder in land administration. There are clear procedures on how levies shall be paid and re-channeled to peri-urban zones. But the study found that upon payment of a once off purchase fee of the land from the local Chief (the traditional leader), most of the households do not pay their monthly levies.

The presence of a parallel administration structure at the local municipality on one hand, and traditional leaders on the other, results in a situation where neither the traditional authorities nor the municipality are accountable for the lack of provision of services. The local municipality blames the traditional leaders for creating settlements ahead of planning, while the traditional leaders blame the local municipality for failing to deliver services for the South African citizens. In turn, this blame game leads to a lack of accountability between the citizens and service providers. The survey showed that peri-urban residents are simply exercising the right to difference, and the right to choose, as they identify with the local municipality structures for service provision, and traditional leaders for land property rights.

A. Waste Management

Waste collection in the villages is organized through pick-up services at designated points along the R524 road. The collection points facilitate for the staff to collect packed household waste for disposal at the designated and open landfill sites. In the villages without pick-up services, waste is left illegally on the dry riverbeds and into the rivers. The garbage is often hidden to evade the full wrath of the law. Some of the sampled villages are usually clean, whereas in some others, the illegal dumping is common and an eye sore. Some families burn their waste, while others do not. Instead, they drop their waste in public spaces that become dirty. Unfortunately, this waste dumping contributes to outbreaks of diseases such as typhoid and cholera.

A. Water

The study revealed that water provision by the local municipality is not meeting the requirements of all the peri-urban villages. The issue of water scarcity is prevalent in all the studied villages, including those that are endowed with a municipal supply. Tshirolwe and Mabirimisa villages in the periphery of Makhado Biaba Town did not have water services. As a result, to get a constant supply of water for household use such as drinking, cooking, bathing, and washing, the economically capacitated households drill boreholes and erect water storage facilities that are referred to as the JoJo tanks. However, most of the sampled residents are not economically capacitated to drill boreholes because it costs around R16,000 to R20,000 (Values in South African Rand, 100 Rand for 5.48 American Dollar, 2022-10-24), which is beyond most household income levels (Fig. 4). Instead, most of the households buy water from water merchants at R1.00 per ten liters of water. Some families need to buy water for domestic animals.

A. Roads and Storm Water Drainage Infrastructure

Lack of municipal roads and road maintenance is an important challenge in all the studied villages. The road network consists of gravel roads since tarred roads are not part of the municipality services. The R524 road is the main road in the area is, traversing the villages and connected to the national road, N1. There are several connector roads in the peri-urban villages bringing the traffic from the R524 onto gravel access roads and to the residential units. Such carriageways were built to increase the access and the convenience of the community residents. Most of the roads are bumpy and rocky to travel on as well as bad and unsafe especially during the rainy season when they turn muddy.

B. Economic and Social Aspects and the Continual Influx of Migrants

As such, peri-urban areas provide opportunities for poor families to access valuable and important housing alternatives. The household survey data revealed that some of the people living in the peri-urban villages are migrants from other sub-Saharan countries such as Ethiopia, Malawi, Zambia, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe. Data from the sampled population of the field survey shows that 32% of the people migrated from other parts of Makhado Municipality into the peri-urban villages of Makhado Biaba Town, whereas about 12% migrated from other parts of South Africa as well as from foreign countries. This shows that 44% of the sampled population migrated into the peri-urban villages of Makhado Biaba Town, and 56% were born in the area. They are economic refugees searching for a better life and settle in the peri-urban villages of Makhado Biaba Town. Thus, the border towns shape migrant corridors in various ways and contribute to the rapid urbanizations of such areas. The influx has created urban sprawl, informal settlements, and contribute to shortages in infrastructure service provision. The same influx also means an increase in the value of land in parts of towns, abuses in human rights, and growing tensions between migrants and host communities when competing for scarce urban services (Murillo, 2017).

B. Housing and Non-payment of Municipal Rates and Levies

The survey pointed out that the residents are mostly disgruntled over the provision of municipal services in the sampled villages. One of the main difficulties of the municipality is that the residents in the villages do not pay taxes. It is their largest revenue and without such resource’s the municipalities cannot provide the services as planned. Most of the sampled respondents indicated that they do not pay rates because lack of money due to meager earnings. Only 22% of the respondents said that they pay rates. Under such circumstances, the local municipality is unable to provide adequate services to the peri-urban villages. Therefore, affordability emerges as the main constraint to the payment of municipal services in the peri-urban villages of Makhado Biaba Town. Figure 4 shows the income levels of the sampled community residents in the peri-urban villages of Makhado Biaba Town.

In 2019, most of the community residents (34%) were unemployed, 21% were retired pensioners, and only 22% were formally employed. The bulk of those who had formal jobs earned R3,500 per month, or less. In other words, the survey showed that most of the inhabitants survived on government grants, agriculture production, and informal activities such as petty trading.

B. Social Housing

The National and Provincial government in South Africa has a responsibility to provide social housing to citizens who earned R3500 or less. Housing is typically delivered through the Reconstruction Development Program (RDP) where low-income beneficiaries are given title deed houses in urban and peri-urban areas (Nokulunga et al., 2018). Households living in Mabirimisa Village and other parts of the peri-urban zone of Makhado Biaba Town have benefited from the RDP government social housing scheme.

C. Land use changes and their effects

By the mapping and change detection analysis, it was recorded significant changes in land use within the study area and its surroundings between 1990, 2014, and 2020 (Figs. 5, 6, 7, Table 1). By comparing Figs. 5 and 7, one can see that the most pronounced changes are increases of built-up land and cultivated land at the expense of shrubland, grassland, and forest land. There is still an increase of forest land (Table 1) because of increases in other areas. Also, there is an increase of barren land, and interestingly, an increase in waterbodies, while a decrease in wetlands. Comparing Tables 1 and 2 indicates that the land use changes within the study area to a large extent follow the same trends as for the entire Limpopo Province. One exception found is the decrease of cultivated land within the Limpopo Province.

The study documented the expansion of peri-urban villages of Makhado Biaba Town extends into surrounding forests and mountains, badly influencing ecologically sensitive areas. In areas without electricity families are collecting firewood for cooking and fuel. Figure 8 shows the number of respondents who believe that the expansion has either impacted the natural environment positively, or negatively, or who were neutral about it. The natural environment aspects recorded include air, soil, open fields, forests, rivers, mountains, and wetlands. Respondents reflected on whether the physical expansion of Makhado Biaba Town negatively impacted the natural environment, or not. Results indicated, for example, that respondents think that an uncontrolled expansion in villages such as Maphakophele will have strong negative effects on ecosystems such as soil, parks, rivers, urban green space, and wetlands. Forests and trees provide both supporting and regulating ecosystem services. For example, tree leaves perform photosynthesis which by producing carbohydrates is a supporting service for life. The photosynthetic process of assimilating CO2 from the air to produce carbohydrates is also a regulating service by reducing the level of CO2 in the atmosphere. Other examples of important regulating ecosystem services are related to the water retention capacities of forests. By retaining water, forests not only mitigate droughts but also reduces run-offs and thereby the risk of flooding and related damage.

Consequently, the negative effects on ecosystems and the animals are dismal. Observations revealed that some households get firewood from forests and mountains, a social and traditional practice that delimits the future ecosystem services. The wetlands are also sensitive and important ecosystems threatened by human activities due to newer developments and urbanization. In the area of Makhado Biaba Town, the wetlands are used for construction of houses because of the high demand on land for developments, even if they are not adapted for construction of houses.

Makhado Biaba Town is in the Vhembe Biosphere Reserve, the largest natural reserve in South Africa. The reserve consists of mountain ranges and ecologically sensitive areas such as wetlands, rivers, forests, and streams. As towns and villages expand, residential development is encroaching into ecologically sensitive areas where the local municipality finds it difficult to extend infrastructure to provide basic services such as sewers, roads, and water. Furthermore, some houses are built on steep slopes which are not suitable for houses, but they are of high interest due to the beautiful environment.

Discussion and Recommendations

The purpose of the paper is to highlight the impact of the increased peri-urban expansion of the small rural town of Makhado Biaba into adjacent villages. A common approach in studies of suburbanization is to see them as outgoing processes related or dependent on the power and organizational core of cities. Current study follows the same logic. The study has a threefold purpose as presented below.

First, the objective was to study the municipal and ecosystem services available in Makhado Biaba Town and its urban villages. The service provision in the core and in the urban periphery was documented by the students. They targeted five categories of livelihoods assets referring to the resource base of a community, namely, human, natural, financial, physical, and social capital as presented by Carney (1998). The national planning and policies clearly favor the inhabitants in the municipal core, and to a lesser extent, the families in the villages at the margin and in the hands of the customary law, which is part of the formal national system of governance. The state of art of the double systems for local governance has a bearing on the livelihood conditions and, consequently on the wellbeing of the inhabitants, according to the survey.

By 2050, the urban area use in sub-Saharan Africa is projected to increase twelvefold (Dodman et al., 2017). Since many of the migrants are poor and cannot afford to live near the core, they build houses in the natural environments outside the municipality borders where there is no infrastructure. The municipalities do not have budgets or financial assets to build new houses. Instead, new settlements take place without their permission outside the municipal boundaries. The municipality finds it difficult to manage the large immigration and does not have the means to build enough homes or to develop the municipal sufficiently services. A symptom of the pressure for houses was documented when community resident’s peri-urban villages of Makhado Biaba Town erected residential units ahead of municipal service provision. This approach to spatial planning assumes an Occupy-Build-Plan-Service Model as opposed to the Plan-Service-Build-Occupy model (Sliuzas et al., 2010:69). The challenges also include building materials, quality of housing, and access to services linked such housing developments remain. Such leapfrogging urbanity takes place just outside the municipal boundaries and on land bought from the traditional landowners. Makhado Biaba Town attracts poor migrants and families arrive in the villages only to be met with almost no public services. Some of them stay a short time, while others tend to stay longer time, or settle down on rural land. Such instability gives the socio-economic issues yet layer of issues to be handled. Consequently, most of the peri-urban developments are sprawling in spaces where municipal service infrastructure is not available. The survey shows that several municipal services are available, but only in the core of the municipality.

The incoming families understand their negative effects on available ecosystem services such as water, forest, and wetlands but they depend on such services to cover their daily needs. Unfortunately, they do not find any other possibilities than to make use of, for example, trees to heat their homes and for cooking. Some residents within the peri-urban area practice farming and they grow crops such as maize, groundnuts, and millet through tilling land. Domestic animal production is also enabled because of the leftovers of the grazing area and forests. However, is peri-urban expansion into the villages extending onto mountains and forests destroying the natural environment. These ecosystems are important for grazing domestic animals, and as such, domestic animals now hardly survive because developments are taking place where they used to graze. The peri-urban villages of Makhado Biaba Town present a lot of ecosystems services critical to the survival and household livelihoods (Phaswana, 2020).

The landscape change shows that the cultivated landscape area is increasing at the expense of grasslands and shrubland (Tables 1 and 2). A reason to this change is that people no longer practice agricultural activity because their farms are no longer productive, and thus, sell their land at a higher amount compared to the amount they get through subsistence farming. Subsistence farming and farm work generally decreased and is presented as the least preferred livelihood activity. This is because new urban development invades farmland. The causes of peri-urban expansion in Makhado Biaba Town are not different from those generally presented in other settings globally. These include availability of job opportunities, access to better services, migration, easy access to land for housing, continuance of nostalgic rural lifestyles, and cheap cost of living (Phaswana, 2020).

The findings reveal how the underlying factor of urbanization acts as a driver for landscape change. The overall observation is the high level of poverty impeding on the fulfillment of existing long-term goals of development and the required effort to achieve the SDGs, in which nature is an important part. As of now, the progress of modern mainstream development in the Makhado Biaba Town urban area is messy, having in mind the lack of resources and the double system of governance in the Limpopo Province. The study found that there are several kinds of shortcomings and challenges related to development of socio-economic aspects and ecosystem services. The low level of societal resources, such as educational, health and care services, and lack of employments together with the dismal modern infrastructure (safe tar roads, water, garbage collection, and electricity), shows that the development and wellbeing are not progressing as planned. These deficiencies of a modern infrastructure usually result in diseases becoming widespread among poorer households (Darkey & Visagie, 2013).

Second, to inquire the municipal challenges and opportunities related to the provision of services in Makhado Biaba Town. In low-income urban areas, there are often ways of getting services without paying fees and this is also the case in studied area. However, the Makhado Local Municipality is required by law to set aside a budget to finance service provision in areas under its jurisdiction, also when their customers do not pay for the services such as electricity of water. Data from interviews with officials from the local municipality shows that some areas of Makhado Local Municipality collect their revenue through municipal rates and billings, for example, in Louis Trichardt. However, it is impossible for the Makhado Local Municipality to provide adequate municipal services in case that the customers do not pay for their services. The result of non-payment is that some zones under the same municipal area can access adequate services while others are underserviced. This shows that the case is not about the ability to pay but the ability to make families pay pointing toward the need for updated and better ways of collecting rates and taxes. It is somewhat difficult in the villages where municipal resident databases are needed to identify the names of people who should pay rates and levies. However, such registers were absent in the surveyed villages. Whenever the community residents of Makhado Biaba Town peri-urban villages are unable to get adequate services, they resort to protests strengthen patterns of conflicts. Furthermore, the unsustainable conditions and the deterioration of environmental resources together with the effects of climate change impede on economic growth, resilience, and future prosperity. For instance, there are no ongoing project toward implementing SDG 11, since that is a state priority. The recommendation from this study encouraged the sustainable livelihood by encouraging agricultural production and nature conservation. Conserving natural ecosystems, building horizontally, and enforcement of building codes are the major important elements that can harness unsanctioned spatial expansion while ensuring sustainable human settlements (Phaswana, 2020).

The double system of governance (the state and the customary law) fragments the public affairs and governance, impeding on the overall development and prosperity. The two system of governance are rooted in separate development logics and partly embedded in separate value systems. The formally accepted system of customary law acts in other ways than the municipality and conflicting views regarding the role of nature in cities imply a conflict of goals.

In addition, cultural factors such as different traditions that varies between groups of inhabitants who move into these areas come into play. So far, the modernization is characterized by a local and somewhat unclear process despite the formal national development plans. The lack of a unified and strong leadership and economic resources stands out. For instance, the process of modern mainstream development has not included the ecosystem services impeding on the community resilience. Hence, the survey shows the importance of the residents to collaborate in identifying critical service delivery gaps, especially in the peri-urban villages. The conflict between the dynamic peri-urban villages and the municipal core points in the direction of state policies and requires the interaction of the state level and local affairs to assume responsibility and improve the conditions.

The study revealed that the expansion of peri-urban villages of Makhado Biaba Town into the surrounding forests and mountains negatively impacts the ecologically sensitive areas. For example, in areas without electricity families collected firewood for cooking and fuel. Figure 8 shows the number of respondents who believe that the expansion impacted the natural environment positively, negatively, or are neutral. The natural environment aspects recorded include air, soil, open fields, forests, rivers, mountains, and wetlands. These respondents also reflected on whether the physical expansion of Makhado Biaba Town negatively impacted the natural environment, or not. Results indicated, for example, that respondents think that an uncontrolled expansion in villages such as Maphakophele had strong negative effects on ecosystems such as soil, parks, rivers, urban green space, and wetlands. The usual approach is to study the peri-urban conditions as dependent on a powerful core, often situated in the nearby city. But we find that dynamic changes are taking place outside of the city core and in areas with alternative means of control. This points toward taking the peri-urban areas and their challenges as the point of reference instead of the traditional city or center of power. Hence, a switch of perspective in theory and practice will renew the studies of different kinds of suburbanization processes. Furthermore, when society largely sprawls into the so-called third spaces or no man’s land, it also finishes up generations of human-non-human relationships with nature as well as the indigenous relationships to land that have existed for a very long time (Tzaninis et al., 2021). The peri-urban conditions will bring about other study objects as well as findings. For instance, how will their transformations toward implementing SDG 11 regarding sustainable cities look like and what strategies of development will fulfill their needs?

Third, the goal was to recommend strategies for improved service provision (municipal and ecosystem) in the urban periphery.

The conflict of authority between the municipality and the traditional chiefs which stifles progress in service delivery and future prosperity is core issues to be resolved. The traditional leaders and the municipal authorities both have a responsibility to implement policies toward strengthen the processes of development of Makhado Biaba Town municipal area, including the ecosystem services. Hence, there is a need to establish a common ground in administering the area.

The findings underline that the two systems (state and indigenous) are anchored in different views on the role of nature in cities and villages (Hudalah et al., 2010). In Makhado Biaba Town, there is an integrated development planning (IDP) through which the municipality prepare a strategic development plan which extends over a five-year period (Makhado IDP, 2018/19). The IDP is the principal strategic planning instrument which guides and informs all planning, budgeting, management, and decision-making processes in a municipality. In terms of the Municipal Systems Act (Act 32 of 2000), all municipalities have to undertake an IDP process to produce IDP’s. As the IDP is a legislative requirement, it has a legal status and it supersedes all other plans that guide development at local government level (Phaswana, 2020).

Therefore, further studies that show how can the role of ecosystem services may be understood and put into local practice are recommended. So far, current studies have not explored the role of nature in traditional ways of life, or the policy building on customary law to promote sustainability efforts. The municipal officials need to be given approval and more freedom to be able to administer development imperatives of tribal land as they collaborate with the traditional leaders. The groups of stakeholders at the municipality level should be able to work collaboratively to reduce potential or real conflicts. The local municipality is incapacitated to achieve to fulfill their mandate due to lack of funds. Current funding for municipal service provision comes from the government. Therefore, a suggestion is to broaden and consider more sustainable municipal service finance options to include private stakeholders and industry.

Through such approach and conversations, the residents are taking part in the local organization and will raise their views and concerns for continuous service delivery improvements. The process may help in pooling resources as some community individuals can volunteer to work on a mechanism designed to pool efforts from the community. The study clearly demonstrates the need for the local municipalities to promulgate urban boundaries through forward planning functions before peri-urban zones are invaded for other new developments. As the peri-urban villages shift to the rear of the urban development, new and undocumented residential units emerge. The new residential developments require adequate municipal services, yet they were developed ahead of municipal development plans or outside the municipality spatial development zones.

The lack of guidance regarding the role of ecosystem services in the core and the peri-urban areas has given the current process of modernization and development a slow start in the region. For instance, sustainable cities are a global recommendation by the UN, called SDG11 and as such supported by the South African state to be introduced by the municipality (UN, 2015). In other words, state policy translates into municipal policies and implemented at the core, but also adopted by customary law and spreading to the villages. So far, the mainstream development has not included the ecosystem services, and it will have to be handled by the closely linked political and organizational institutions. Perhaps changes in the planning process will enable the implementation of such policies together with required information or educational resources. As of now, municipalities are organized in silos and it does not favor the development of relevant strategies toward sustainable city development. A closer interaction between the formal government and the local communities would facilitate the implementation of sustainable policies.

Although there is a lack of guidelines for the role of ecosystem services and human wellbeing, people practice agricultural activities for sustaining their living, however, on a limited scale because of reduced arable land. As a result, will people living in peri-urban areas adapt to urban livelihoods because people are now abandoning their farmland due to drought and other urbanization pull factors in the town. Agricultural area is converted to industrial, commercial, and residential area. Planning policies and strategies for peri-urban areas must therefore take into account the variety of all different areas in the urban and peri-urban environment that will contribute to a more sustainable development (Wandl & Magoni, 2017). By revisiting the ecological dimension, we can create more room for nature also beyond human services and solutions, and especially in the urban areas, to build in more space for natural processes, ecosystem functioning, and long-term unpredictability (Randrup et al., 2020).

The findings underline that the two systems (state and indigenous) are anchored in different views on the role of nature in cities and villages. Therefore, further studies that show how can the role of ecosystems may be understood and put into local practice are recommended. So far, current studies have not explored the role of nature in traditional ways of life or the policy building on customary law to promote sustainability efforts.

Today’s double system can benefit from a reorganization in which current land administration system for peri-urban villages changes toward the co-creation of new policy and planning with traditional leaders and local municipalities working together to update the distribution and access to land property rights. It can be achieved if the municipalities improve forward planning or master planning imperatives, which go beyond the peri-urban boundaries. To achieve this improvement, a network approach can be adopted (Hudalah et al., 2010) building on discussions between interested stakeholders: politicians, environmentalists, municipalities, academia, and the residents. Networking implies social movement, effective collective action, and improved democratic governance respectively (Castells, 1996; Hudalah et al., 2010). Implementing such an approach is critically needed. It would be integrative, inclusive, and flexible as well as transparent aiming at ironing out the conflicts of the quality of the environment, regional sustainability, and preservation of cultural values.

Today’s double system can benefit from a reorganization in which current land administration system for peri-urban villages changes toward the co-creation of new policy and planning with traditional leaders and local municipalities working together to update the distribution and access to land property rights. It can be achieved if the municipalities improve forward planning or master planning imperatives which go beyond the peri-urban boundaries. To achieve this improvement, a network approach can be adopted (Hudalah et al., 2010) building on discussions between interested stakeholders: politicians, environmentalists, municipalities, academia, and the residents. Networking implies social movement, effective collective action, and improved democratic governance, respectively (Castells, 1996; Hudalah et al., 2010). Implementing such an approach is critically needed. It would be integrative, inclusive, and flexible as well as transparent aiming at ironing out the conflicts of the quality of the environment, regional sustainability, and preservation of cultural values.

To ensure access to municipal services by all residents in the studied areas, the findings stress the need for a guided urban development, urban expansion, and settlement upgrading programs in peri-urban zones. In order to be able to create and develop a more sustainable society in these areas, an increased understanding is required at the municipal level regarding the interaction between individuals, nature, and the ecosystem services where settlements are created. In addition, better cooperation between the municipality and the traditional authorities is required. In order to reduce the negative effects of the ongoing urbanization, a holistic approach is needed that includes a balance between ecology and a socio-economic dimension. For instance, recurrent and well-structured dialogs with the local organizations and the concerned households to identify delivery failures and enabling growth and prosperity is strongly recommended.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Allen, A. (2003). Environmental planning and management of the peri-urban interface (PUI). Perspectives on an emerging field. Environment & Urbanization, 15(1), 135–147.

Allen, A. (2010). Neither rural nor urban: Service delivery options that work for the peri urban poor. In M. Khurian & P. McCarney (eds.), Peri-urban water and sanitation services: policy, planning and method. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-9425-4_2

Antrop, M. (2004). Rural-urban conflicts and opportunities. In R. Jongman (Ed.), The new dimensions of the European landscape, pp. 83–91. Wagening UR Frontis Series, Springer, The Netherlands.

Batley, R. (1996). Public–private relationships and performance in service provision. Urban Studies, 33, 723–751.

Berkes, F. (2017). Environmental governance for the Anthropocene? Social-ecological systems, resilience, and collaborative learning. Sustainability, 9, 1232. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9071232

Birkmann, J., Garschagen, M., Kraas, F., & Quang, N. (2010). Adaptive urban governance: New challenges for the second generation of urban adaptation strategies to climate change. Sustainability Science, 5, 185–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-010-0111-3

Carney, D. (1998). Implementing the sustainable rural livelihoods approach. In Paper presented to the DfID Natural Resource Advisers’ Conference. London: Department for International Development.

Castells, M. (1996). The rise of network society. Oxford: Blackwell.

Chanza, N., & Musakwa, W. (2021). "Trees are our relatives": Local perceptions on forestry resources and implications for climate change mitigation. Sustainability, 13(11), 5885.

Community Survey Report. (2016). Statistical release. Government of South Africa.

Costanza, R., Atkins, P. W. B., Hernandez-Blanco, M., & Kubiszewski, I. (2021). Common asset trusts to effectively steward natural capital and ecosystem services at multiple scales. Journal of Environmental Management, 280, 111801.

Daily, G. C., Polasky, S., Goldstein, J., Kareiva, P. M., Mooney, H. A., Pejchar, L., Ricketts, T. H., Salzman, J., & Shallenberger, R. (2009). Ecosystem services in decision making: Time to deliver. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 7(1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1890/080025

Darkey, D., & Visagie, J. (2013). The more things change the more they remain the same: A study on the quality of life in an informal township in Tshwane. Habitat International, 39, 302–309.

Department of Forestry, Fisheries & the Environment. (2022). South african national land cover. Retrieved May 3, 2022, from https://www.dffe.gov.za/

Dubazane, M., & Nel, V. (2016). The relationship of traditional leaders and the municipal council concerning land use management in Nkandla Local Municipality. Indilinga, 15(3), 222–238.

Dodman, D., Leck, H., Rusca, M., & Colenbrander, S. (2017). African urbanization and urbanism: Implications for risk accumulation and reduction. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 26, 7–15.

Duvernoy, S., Zambon, I., Sateriano, A., & Salvati, L. (2018). Pictures from the other side of the fringe: Urban growth and peri-urban agriculture in a post-industrial city (Toulouse, France). Journal of Rural Studies, 57, 25–35.

Environmental Systems Research Institute (Esri) (2022). Basemap world imagery: Esri, Maxar, Earthstar Geographics, and the GIS User Community. Retrieved May 10, 2022, from within the ESRI software ArcGIS Pro.

GADM (2019). South Africa. Retrieved April 21, 2019, from https://gadm.org/index.html

Gumbo T. (2014). The architecture that works in housing the urban poor in developing countries: Formal land access and dweller control. Sustainable Development Programme at the Africa Institute of South Africa (AISA). AISA POLICY brief Number 105. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.4512.2247

Gumbo, T. (2015). Re-thinking housing infrastructure development approaches: Lessons from Zimbabwe; 10 – 26. In Proceedings of The International Conference On Infrastructure Development a75nd Investment Strategies For Africa DII – 2015. Livingstone.

Haase, D., Frantzeskaki, N., & Elmqvist, T. (2014). Ecosystem services in urban landscapes: Practical applications and governance implications. AMBIO, 43, 407–412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-014-0503-1

Harvey, D. (2003). The right to the city. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 27(4), 939–941.