Abstract

Rapid urbanisation and food system transformation in Africa have been accompanied by growing food insecurity, reduced dietary diversity, and an epidemic of non-communicable disease. While the contribution of wild and indigenous foods (WIF) to the quality of rural household diets has been the subject of longstanding attention, research on their consumption and role among urban households is more recent. This paper provides a case study of the consumption of WIF in the urban corridor of northern Namibia with close ties to the surrounding rural agricultural areas. The research methodology involved a representative household food security survey of 851 urban households using tablets and ODK Collect. The key methods for data analysis included descriptive statistics and ordinal logistic regression. The main findings of the analysis included the fact that WIFs are consumed by most households, but with markedly different frequencies. Frequent consumers of WIF are most likely to be female-centred households, in the lowest income quintiles, and with the highest lived poverty. Frequent consumption is not related to food security, but is higher in households with low dietary diversity. Infrequent or occasional consumers tend to be higher-income households with low lived poverty and higher levels of food security. We conclude that frequent consumers use WIF to diversify their diets and that occasional consumers eat WIF more for reasons of cultural preference and taste than necessity. Recommendations for future research include the nature of the supply chains that bring WIF to urban consumers, intra-household consumption of WIF, and in-depth interviews about the reasons for household consumption of WIF and preferences for certain types of wild food.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Across the African continent, hyper-urbanisation is transforming urban food supply systems (Crush & Battersby, 2016), creating obesogenic food environments (Bosu, 2015; Kroll et al., 2021), and driving a marked deterioration in the quality of urban diets (Frayne et al., 2014; Steyn & Mchiza, 2014). This accelerating ‘nutrition transition’ is characterised by reduced dietary diversity (Gassara & Chen, 2021); lower intake of complex carbohydrates, dietary fibres, fruits, and vegetables (Holdsworth & Landais, 2019); increased intake of energy-rich cereals, fats, and sugars (Holmes et al., 2018); and mass consumption of highly processed foods (Reardon et al., 2021). The lack of access to and intake of healthy foods is driving a silent epidemic of non-communicable disease (NCDs) including obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (Bigna & Noubian, 2019). Gouda et al. (2019) calculate that there has been a significant increase in disability adjusted life years (DALYs) due to non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa in the last three decades, from 90.6 million in 1990 to 151.3 million in 2017. They further project that by 2030, NCDs associated with the nutrition transition will become the leading cause of mortality on the continent. In Namibia, the WHO (2016) notes that non-communicable disease as a cause of premature mortality, disability, and total health loss (DALYs) rose significantly in importance over the period 2000 to 2013. In this context, the changing nature and composition of household diets becomes of particular importance (Kazembe et al., 2022a; Nickanor & Kazembe, 2016).

Wild and indigenous foods (WIF) have long been a key component of household diets in rural Africa (for example, Bharcucha and Pretty, 2010; Sardeshpande & Shackleton, 2020a, 2020b; Zinyama et al., 1990). However, as Hunter and Fanzo (2013) note, ‘terms such as underutilised, neglected, orphan, minor, promising, niche, local and traditional are frequently used interchangeably to describe these potentially useful plant and animal species, which are not mainstream, but which have a significant local importance’. Consistent with the conventional view that food insecurity in Africa is primarily a rural phenomenon (Crush & Riley, 2019), most research attention has been paid to the potential of wild foods to improve food security and dietary diversity in rural households (e.g. Fanzo et al., 2013; Hickey et al., 2016; Kasimba et al., 2018; Kazungu et al., 2020; Ngome et al., 2017, 2019; Paumgarten et al., 2018; Powell et al., 2015; Rasmussen et al., 2020; Shackleton & Shackleton, 2004). In cities, many at a distance from sites of natural biodiversity, there is a perception that wild and traditional foods are not easily accessible and therefore do not represent a viable or even partial solution to mitigating food insecurity and increasing dietary diversity.

The rural bias of food security-related research on wild and traditional foods has recently been corrected by case studies of urban wild food consumption in several African cities. In Uganda and South Africa, for example, urban foraging for wild foods provides an important source of dietary supplement among low-income households (Garekae & Shackleton, 2020a; Mollee et al., 2017). Urban foraging ameliorates ‘the monotonous diets of some households and in turn promoting dietary diversity’ (Garekae & Shackleton, 2020a). Other relevant studies of the impact of urban foraging on urban diets include Garekae and Shackleton (2020b), Garekae et al. (2022), and Kaoma and Shackleton (2014). Wild food consumption can improve general household food security but does not mitigate food insecurity among low-income urban households (Chakona & Shackleton, 2019). In Kenya, Gido et al. (2017) argue that the consumption of indigenous leafy vegetables is higher in rural than urban areas but that improved market supply chains would enhance urban availability and access.

Although urban foraging is a global phenomenon, in most cities and towns, the volume of wild foods available to foragers is likely to be fairly limited and not easily accessible to the population at large (see, e.g. McLain et al., 2014; Shackleton et al., 2017). However, Sneyd (2015, 2016) shows that in Cameroon, a wide variety of forest foods are actually collected outside urban areas and transported and sold in urban markets by informal traders. At the same time, while household food budgets include a significant spend on wild/traditional foods, they are being increasingly displaced by cheaper food imports, including rice (Sneyd, 2013). More research is thus needed on the market and nonmarket channels by which wild/traditional foods from rural areas arrive in cities and how accessible they are to consumers. Another key question raised by the case study literature is the relative importance of wild/traditional foods relative to other types of purchased food in urban diets, including fruit and vegetables that are mass produced on commercial farms; imported and locally grown starchy staples such as rice and maize; and highly processed foods rich in sugar, oils, and fats. In fact, the literature is largely silent on the significance and future of wild/traditional food in urban food systems increasingly dominated by formal food retail, including supermarkets. Finally, while some case studies do attempt to situate the contribution of wild/traditional foods to improving dietary quality and food security, none claim that their consumption will avert the growing crisis of urban food insecurity, dietary deprivation, and the negative health consequences of the nutrition transition.

Against the backdrop of the under-researched role of WIF consumption and food insecurity in African cities, this paper presents a case study from the rapidly urbanising northern region of Namibia. To date, studies of wild and indigenous foods in Namibia have followed the conventional path, focussing on collection and consumption in rural areas of the country. Ethnobotanical knowledge of the types, range, and edibility of wild fruits is extensive amongst rural residents of northern Namibia. There are at least 25 different species of fruit trees with indigenous names used for food and/or medicinal purposes, as well as a variety of edible leafy vegetables, insects (such as mopane worm) and frogs (see, e.g. Chataika et al., 2020; Cheikhyoussef & Embashu, 2013; Kamwi et al., 2020; Maroyi & Cheikhyoussef, 2017; Mushabati et al., 2015; Nantanga & Amakali, 2020; Okeyo et al., 2015; Thomas, 2013). The collection of wild fruits tends to be higher among households with limited cash income and greater food insecurity, suggesting that own consumption may primarily be a survival mechanism (Musaba & Sheehama, 2009).

The case study literature on rural Namibia suggests that there are ongoing shifts in the role of wild and indigenous foods that could impact urban consumers and food environments. First, detailed knowledge about wild foods tends to reside with older members of the community, who traditionally pass on this information to their younger relatives. However, as rural diets begin to rely more on food purchase and food preferences change, younger people seem less interested in acquiring this knowledge. They prefer the convenience of not having to forage wild foods and eating imported alternatives when available (e.g. store bought spinach and broccoli over wild leafy greens) (Maroyi & Cheikhyoussef, 2017; Mushabati et al., 2015). Second, the destruction of natural habitat through overgrazing and forest destruction for fuel is being exacerbated by climate change (see, e.g. Haindongo et al., 2022; Kamwi et al., 2015, 2018; Kamwi & Mbidzo, 2022; Mulwa & Visser, 2020; Wingate et al., 2016). Although the evidence is sketchy, this is having a negative impact on the availability of wild foods. As one livestock farmer in the Kunene region of Namibia observed: ‘a long time ago, people survived on these; wild fruits and wildlife. Now there nothing. We rarely get fruits from the wild, and all the wild animals are no longer here’ (cited in Inman et al., 2020).

Rural food insecurity and declining agricultural productivity mean that households are increasingly dependent on cash income to purchase food and other basic needs. This, in turn, has exacerbated rural to urban migration as working-age household members move to cities in search of employment and other income-generating activity. Household members in the city remit income to their rural families and the latter regularly send agricultural produce to their relatives in the city. This phenomenon, of rural to urban food transfers or remittances, has been extensively documented in Namibia since it was first observed by researchers in the early 2000s (see Frayne, 2004, 2005, 2007; Frayne & Crush, 2018). In addition to pearl millet (mahungu), wild foods are the most important type of foodstuff transferred. For example, a survey of low-income households in the capital, Windhoek, found that 62% of households received food transfers from rural areas and that of these 50% received wild foods (Frayne, 2010). Many rural households have also turned wild foods into income-generating commodities. Therefore, informal supply chains have emerged to deliver wild foods to urban centres where they are sold in formal and informal markets and by street vendors.

This paper contributes to the literature on food security and WIF consumption in African cities by examining the extent, frequency, and consumption of consumption by urban households in urbanising northern Namibia. Section 2 describes the study site and source of data for this article and the research methodology of a representative household food security survey conducted in 2018. Sect. "Methods" provides a descriptive statistical analysis of the frequency of WIF consumption and identifies the types of households that are most likely to be frequent consumers. Sect. "Results" also models WIF consumption as a whole and the likelihood of different types of household consuming WIF. Sect. "Discussion" looks at the significance of the results and the Conclusion of the article identifies areas for future research that builds on these findings.

Methods

Study Site

The research for this article was conducted in the urban corridor of northern Namibia which links the three secondary cities of Oshakati, Ondangwa, and Ongwediva along a 30-km stretch of highway in the Oshana region (Fig. 1). The urban corridor is approximately 5-km wide on both sides of the highway, which is the major route for transborder trade between Namibia and Angola (Nangulah & Nickanor, 2005). Oshakati and Ongwediva are effectively a single urban centre with boundaries that have blurred over time, while Ondangwa is separated from the other two by about 28 km. The total area of the corridor is therefore about 150 sq km, although there are still rural sections between Ondangwa and Ongwediva. At the time of the last Census in 2011, the total urban population of the corridor was 76,000 and is projected to have reached 110,000 in 1921 with a growth rate of 5–8% (NSA, 2014). Oshakati is the largest centre (35,600 in 2011), followed by Ondangwa (21,000) and Ongwediva (20,000). The corridor is surrounded on all sides by scattered rural villages primarily engaged in crop cultivation of staple foods such as mahangu (millet) and cattle rearing (Mulwa & Visser, 2020).

The food system in the urban corridor is a complex mix of long-distance and local supply chains and formal and informal food retail outlets (Kazembe et al., 2022b; Nickanor et al., 2022). The formal system is increasingly dominated by local and international supermarket chains based in South Africa and Botswana (Nickanor et al., 2017). Most of the fresh and processed food on supermarket shelves is imported into the corridor through long-distance supply chains originating in private commercial farms and ranches in Namibia, abattoirs and milling plants in Windhoek, supermarket distribution centres in South Africa, and food imports direct from Europe and Thailand (in the case of rice). The informal food sector consists of small-scale food retailers operating in formal and informal market places, mobile vendors selling house-to-house, and tuck shops (tin structures in informal settlements). High levels of food insecurity and urban poverty are well documented (Nickanor et al., 2022).

The most common wild and indigenous foods consumed in northern Namibia consist of three main types: (a) plants such as evana/ekaka/ombonga (spinach), omakwa (baobab fruit), and eendunga (palm fruit); (b) insects such as oothakulatha (flying ants) and omagungu (mopane worms); and (c) wildlife such as eeshi (fish), omafuma (frogs), and uunyenti (squirrels) (Table 1). Due to the proximity of the rural areas, wild foods are easily accessible by urban households in the corridor. Wild foods cross the rural–urban interface in several ways, including being sent by rural family members, by household members foraging or catching wild foods in rural areas themselves, and being transported by informal vendors. Some vendors collect wild foods themselves in rural areas, others purchase them from rural households and sell them to consumers in formal and informal markets.

Data Collection

Data for this study comes from a representative household survey conducted by the authors in 2018 in the urban corridor. The survey sample was based on a two-stage cluster sampling design. In the first stage, 35 enumeration areas (primary sampling units or PSUs) were randomly selected with probability proportional to population size. The PSUs were drawn from the master sampling frame established for the 2011 Population Census. The target PSUs included 18 in Oshakati, 7 in Ongwediva, and 10 in Ondangwa. At the second stage, a fixed number of 26 households were systematically selected in each PSU, giving a total sample size of 851 (491 in Oshakati, 146 in Ongwediva, and 214 in Ondangwa). A questionnaire collecting detailed information on household structure, food consumption patterns, and food sourcing behaviour was programmed on tablets using ODK software and administered face-to-face to the household head or their representative.

Variables

The household-level dependent variable for the analysis is frequency of consumption of 16 common wild and indigenous foods during four time periods (Table 1). For the analysis, these were binned into two categories: (a) frequent consumption defined as daily (at least five days per week) or weekly (at least once per week) and (b) occasional consumption defined as biweekly (at least twice per month), and monthly (at least once per month).

Several independent variables were selected for the analysis of WIF consumption: (a) the categorical variable geographical location; (b) household characteristics including the categorical variables housing type and household structure and the ordinal variable lived poverty; and (c) food insecurity indicators including the ordinal variables food security and dietary diversity (Table 2).

Some commentary on the choice of variables is warranted. First, the survey was administered in all three towns along the corridor with sample size proportional to population. The location variable is therefore designed to capture whether town size affects the probability of WIF consumption. Second, all three urban centres have formal neighbourhoods occupied by middle and higher-income residents and informal settlements occupied by low-income residents. The survey collected data on the type of housing occupied by surveyed households, and the variable Housing type is designed to capture differences in WIF consumption in formal and informal areas of the corridor. Third, to capture relative household poverty and its association with WIF consumption, we selected two variables. Household income is an indicator of relative wealth and poverty and is categorised into income quintiles. The lived poverty index (LPI) is designed to capture the relationship between WIF consumption and household access to five basic needs and the infrastructure that provides them (Dulani et al., 2013; Frayne & McCordic, 2015). The final two variables, food security and dietary diversity, are designed to capture the relationship between WIF consumption and food and nutritional insecurity. Our working hypothesis is that frequent WIF consumption is more likely amongst food insecure households as a way of supplementing diets of limited quantity and quality. However, this may be complicated by the fact that WIF consumption is known to have other derived values beyond enhancing food security, including for cultural or ceremonial purposes. Based on this analysis, the surveyed households can be distributed between the different categories (Table 3).

Results

Frequency of WIF Consumption

Most households in the corridor consumed some wild and indigenous foods. A total of 817 of 846 households (or 90%) included at least one WIF in their diet in the month prior to the survey. Of the different wild foods, nearly two-thirds consumed evanda/ekaka/omboga (spinach), eeshi (fish), and eembe (bird plum); a third consumed omagungu (mopane worm); and a quarter ate oontangu (kapenta) and eendunga (palm fruit) (Table 4). Less than 10% had eaten foods such as owawa (mushrooms), okadhila (birds), omakwa (baobab fruit), oothakulatha (flying ants), okalimba (rabbits), and uunventi (squirrels).

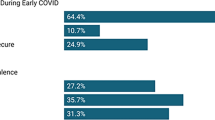

However, only 6% of the households consumed wild foods at least 5 days a week (Fig. 2). Another 14% incorporated wild foods into their diet at least once a week. The most frequent consumption category was at least once a month, with just over half of the households. The frequency of consumption varied considerably by type of wild food (Fig. 3). Daily and weekly consumption is dominated by eeshi (fish) (at 61% of consuming households). Other frequently consumed foods include evanda/ekaka/omboga (dried and dried spinach) at 38% and eembe (birdplum) at 31%. All the other wild foods are consumed frequently by less than 20% of households. Most other wild foods are consumed only once or twice a month by households.

Household characteristics and frequent WIF consumption

Frequent consumption of wild and indigenous foods varied with some household characteristics and not with others (Table 5). The location of a household in the corridor, household structure, household income, and lived poverty are all related to frequent WIF consumption. Frequent consumption is highest in Ondangwa (at 24% of households) and lowest in Ongwediva (13%). Female-centred and single person households have the highest proportion of frequent consumers, at 22% and 24%, respectively, and nuclear households the lowest (at 14%) (p = 0.040). Household income has the strongest relationship with frequent consumption of WIF (p = 0.005). Frequent consumption was highest within the lowest income quintiles (at 28% and 24%, respectively) and lowest within the highest income quintile (11%). There was a similar association with lived poverty, since the frequency rate of WIF consumption was higher in households with greater lived poverty (p = 0.011).

However, there was little difference between households in informal and formal housing, with 19% of the former and 20% of the latter being frequent consumers. The other striking result shown is the similarity between food secure and food insecure households, with around 20% of both sets being frequent WIF consumers. Frequent WIF consumption does have a stronger relationship with the quality of the household diet. The relationship between WIF consumption and household dietary diversity is stronger but not in the expected direction of improved diversity (p < 0.001). Only 13% of households with a more diverse diet are frequent WIF consumers compared to 24% of households with less diverse diets.

The distribution of the five basic needs of the LPI provides additional information on households that frequently consume WIF (Fig. 4). Lack of cash income is the most important deficit, experienced by 60% of frequent food consumers. Almost 40% of those frequent consumers experienced a lack of cash income several times or frequently during the recall period. The proportion of frequent WIF consumers that experienced a food deficit is just under 30%, but three-quarters of these have a food deficit only occasionally. An absence of electricity is the other important deficit experienced by almost half of the households.

To identify which household characteristics had a statistically significant relationship with overall WIF consumption, we fitted the ordinal logistic regression model to the data. The model assesses the odds (likelihood) of a household with a given characteristic consuming wild foods in the 1-month period prior to the survey (Table 6). The model indicates that the odds of a household consuming WIF are significantly related to three variables: household location, housing type, and household income. Households in Ondangwa (OR = 1.86) and Oshakati (OR = 1.36) are more likely to consume WIF than those in Ongwediva.

Households in formal housing are less likely to consume WIF than those in informal housing (OR = 0.60).

The most significant relationships with WIF consumption are household income and lived poverty. However, the odds of consuming wild foods are the reverse of the frequency analysis. For example, the likelihood of consuming WIF during the course of the month actually decreases with declining income. Households in the lowest income quintile are three times less likely to consume WIF at least once than those in the upper income quintile (OR = 0.31). A similar contrary picture emerges with lived poverty; that is, households with the lowest lived poverty have the highest chance of consuming WIF during the month (OR = 1.55). Other contrary findings include the fact that food secure households are more likely to consume WIF (OR = 1.11), and households with low dietary diversity are less likely to consume WIF (OR = 0.85).

Discussion

The aim of this article was to identify the characteristics of the household that make it more or less likely to consume WIF both frequently and over the course of a month. To better understand the role of wild foods in the diets of urban households, we first focused on building a picture of households that are frequent consumers of WIF. The first important result was that frequent (and occasional) consumption varied by geographical location. Ondangwa, which is more isolated and embedded in its rural surroundings, had the highest rates of consumption. Ongwediva, which is predominantly a commuter town for Oshakati and more middle-class in character, had the lowest rates. Oshakati, the largest centre with its mix of poorer and wealthier neighbourhoods, was in between and has a larger number of formal and informal food outlets.

Frequent WIF consumers were most likely to be female-centred and single person households with low income and high lived poverty. However, almost the same proportion of food secure and food insecure households were frequent consumers of WIF. This suggests that wild food consumption is not frequent or voluminous enough to positively influence the level of food security of the two thirds of households that are food insecure. However, households with lower diversity were twice as likely to be frequent WIF consumers than those with high diversity. These findings suggest that frequent usage of wild foods does not have a marked impact on overall food security in the urban corridor. On the other hand, frequent wild food consumption is more likely for low-income households with limited dietary diversity and higher lived poverty.

The second part of the analysis examined the relationship between household type and overall consumption of WIF. Using logistic regression and odds ratios, a somewhat different picture emerged of the relationship between household income, food security, and consumption of WIFs. As noted, the most frequent consumers of WIF are households with low incomes, high lived poverty, and lower dietary diversity. When WIF consumption is modelled independently of the frequency of consumption, a rather different scenario emerged. That is, households with higher incomes, higher dietary diversity, and lower living poverty had the highest odds of consuming wild food. To explain this seeming paradox, it is therefore important to ask what makes poorer households with limited diets more frequent consumers of WIF as well as what makes wealthier households with diverse diets only occasional consumers of WIF.

For poorer households, wild foods sent from the countryside or purchased from informal food vendors are a cheap and satisfying way to bring some variety to an otherwise meagre and monotonous household diet dominated by cereals such as maize and mahangu (millet). For wealthier households with diverse diets, the occasional consumption of WIF is more a choice than a necessity. For these households, the consumption of WIFs has a value far beyond utilitarian use in improving food security and dietary diversity. Rather, occasional incorporation of wild foods into the diet is more likely a familiar cultural dietary practise with deep historical roots that migrants have brought with them, reflecting the importance of maintaining strong affective links with the rural home and the natural environment.

Conclusion

The transformation of the food system of northern Namibia, the growing role of supermarkets and long-distance supply chains, and the resilience of informal food vending all present urban consumers with a growing variety of types and sources of food, provided that they have the resources to purchase those foods. Furthermore, there is growing evidence that urban diets are becoming more westernised with an accompanying rapid increase in non-communicable diseases (Crush et al., 2021; Kazembe et al., 2022a). The place of traditional rural foods, including wild and indigenous foods, in the context of transformation of the urban and food system is largely unknown and needs more research. This is therefore the first study we know of to systematically address the relationship between rapid urbanisation and wild and indigenous food consumption (WIF) in Namibia. Building on the literature on urban WIF consumption in other countries and rural WIF consumption in Namibia, this is also the first study to examine the extent and frequency of WIF consumption in urban centres by urban households that have strong ties to rural areas.

Urbanisation, food system transformation, and changing consumer habits have not eliminated the appeal of wild and indigenous foods. The household survey found that a majority of households had consumed WIF in the month before the survey. However, there was considerable variation in the way foods were consumed and in the frequency of consumption. The article shows that the most frequent consumers of WIF were low-income households with limited dietary diversity. Although this practice did not appear to improve overall food security, it did mean that it improved dietary diversity. For these households, WIF consumption was more of a necessity to improve the quality of the household diet. On the other hand, households of higher income with diverse diets were the most important occasional consumers of WIF. For these households, improving the quality and diversity of their food intake was likely not the main motivation for WIF consumption. Rather, the consumption of wild foods was a matter of taste and of cultural continuity and connection with rural areas.

This article has shown that urbanisation and the transformation of the food system have not eliminated the appeal of wild and indigenous foods to urban households in Namibia. To better understand the different motivations of low-income and higher-income households suggested by this analysis, further in-depth qualitative research on household reasons for accessing and consuming wild foods and why certain foods are preferred is necessary. This would also shed light on intra-household wild-food consumption. For example, are WIF preferred by older members of the household with stronger rural roots, and what is the attitude of younger people given findings in rural areas that they prefer westernised dietary alternatives promoted by supermarkets?

A second area requiring more research is to understand the supply chains of WIFs from rural to urban areas. There appear to be two main ways in which wild foods enter the urban areas of northern Namibia. The first is through non-market food remittances from rural family members, and the second is through informal collection, distribution, and marketing channels that see WIF sold in formal and informal markets. The precise balance and relative importance of these two channels need investigation. Finally, in light of climate change and the increasing frequency of extreme weather events such as drought and floods, it is important to assess whether the stock of WIF is declining in the areas from which urban households draw these foodstuffs. In other words, is WIF consumption in urban areas a passing phase or is it sufficiently entrenched and viable to continue to meet the food preferences of newly urbanised households?

References

Bharucha, Z., & Pretty, J. (2010). The roles and value of wild foods in agricultural systems. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal British Society B, 365, 2913–2926.

Bigna, J., & Noubian, J.-J. (2019). The rising burden of non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa. The Lancet Global Health, 7(10), E1295–E1296.

Bosu, W. (2015). An overview of the nutrition transition in West Africa: Implications for Non-Communicable Diseases. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 74(4), 466–477.

Chakona, G., & Shackleton, C. (2019). Food insecurity in South Africa: To what extent can social grants and consumption of wild foods eradicate hunger? World Development Perspectives, 13, 87–94.

Chataika, B., Shadeya-Mudogo, L., Achigan-Oko, E., Sibiya, J., & Kwapata, K. (2020). Utilization of spider plants (gynandropsis gynandra, L. Briq) amongst farming households and consumers of northern Namibia. Sustainability, 12(16), 6604.

Cheikhyoussef, A., & Embashu, W. (2013). Ethnobotanical knowledge on indigenous fruits in Ohangwena and Oshikoto regions in Northern Namibia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 9, 34.

Crush, J., & Battersby, J. (Eds.) (2016). Rapid urbanisation, urban food deserts and food security in Africa. Springer Nature.

Crush, J., & Riley, L. (2019). Rural bias and urban food security. In J. Battersby & V. Watson (Eds.), Urban food systems governance and poverty in African cities (pp. 42–55). Routledge.

Crush, J., Nickanor, N. & Kazembe, L. (2021). Urban food system governance and food security in Namibia (HCP Discussion Paper No. 49). Hungry Cities Partnership.

Dulani, B., Mattes, R. & Logan, C. (2013). After a decade of growth in Africa, little change in poverty at the grassroots. (Policy Paper No. 1). Afrobarometer

Fanzo, J., Hunter, D., Borelli, T. & Mattei, F. (Eds.). (2013). Diversifying food and diets: Using agricultural biodiversity to improve nutrition and health. Routledge.

Frayne, B. (2004). Migration and urban survival strategies in Windhoek Namibia. Geoforum, 35(4), 489–505.

Frayne, B. (2005). Rural productivity and urban survival in Namibia: Eating away from home. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 23(1), 51–76.

Frayne, B. (2007). Migration and the changing social economy of Windhoek. Namibia. Development Southern Africa, 24(1), 91–108.

Frayne, B. (2010). Pathways of food: Mobility and food transfers in southern African cities. International Development Planning Review, 32(3–4), 291–311.

Frayne, B., & Crush, J. (2018). Food supply and urban-rural links in Southern African cities. In B. Frayne, J. Crush, & C. McCordic (Eds.), Food and nutrition security in Southern African cities (pp. 34–47). Routledge.

Frayne, B., & McCordic, C. (2015). Planning for food secure cities: Measuring the influence of infrastructure and income on household food security in Southern Africa. Geoforum, 65, 1–11.

Frayne, B., Crush, J., & McLachlan, M. (2014). Urbanization, nutrition and development in Southern African cities. Food Security, 6(1), 101–112.

Garekae, H., & Shackleton, C. (2020a). Urban foraging of wild plants in two medium-sized South African towns: People, perceptions and practices. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 49, 12681.

Garekae, H., & Shackleton, C. (2020b). Foraging wild foods in urban spaces: The contribution of wild foods to urban dietary diversity in South Africa. Sustainability, 12(2), 678.

Garekae, H., Shackleton, C., & Tsheboeng, G. (2022). The prevalence, composition and distribution of forageable plant species in different urban spaces in two medium-sized towns in South Africa. Global Ecology and Conservation, 33, e01972.

Gassara, G., & Chen, J. (2021). Household food insecurity, dietary diversity, and stunting in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Nutrients, 13(12), 4401.

Gido, E., Ayuya, O., Owuor, G., & Bokelmann, W. (2017). Consumption intensity of leafy African indigenous vegetables: Towards enhancing nutritional security in rural and urban dwellers in Kenya. Agricultural and Food Economics, 5, 14.

Gouda, H., Charlson, F., Sorsdahl, K., Ahmadzada, A., Ferrari, A., Erskine, H., Leung, J., Santamauro, D., Lund, C., Aminde, L., et al. (2019). Burden of non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, 1990–2017: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Global Health, 7, e1375-1387.

Haindongo, P., Kalumba, A., Orimoloye, & I. (2022). Local people’s perceptions about Land Use Cover Change (LULCC) for sustainable human wellbeing in Namibia. GeoJournal, 87, 1727–1741.

Hickey, G., Pouliot, M., Smith-Hall, C., Wunder, S., & Nielsen, M. (2016). Quantifying the economic contribution of wild food harvests to rural livelihoods: A global-comparative analysis. Food Policy, 62, 122–132.

Holdsworth, M., & Landais, E. (2019). Urban food environments in Africa: Implications for policy and research. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 78, 513–525.

Holmes, M., Dalal, S., Sewram, V., Diamond, M., Adebamowo, S., Ajayi, I., Adebamowo, C., Chiwanga, F., Njeleka, M., Laurence, C., et al. (2018). Consumption of processed food dietary patterns in four African populations. Public Health Nutrition, 21, 1529–1537.

Hunter, D., & Fanzo, J. (2013). Agricultural biodiversity, diverse diets and improving nutrition. In J. Fanzo, D. Hunter, T. Borelli, & F. Mattei (Eds.), Diversifying food and diets: Using agricultural biodiversity to improve nutrition and health (pp. 1–13). Earthscan.

Inman, E., Hobbs, R., & Tsvuura, Z. (2020). No safety net in the face of climate change: The case of pastoralists in Kunene Region Namibia. Plos One, 15(9), e0238982.

Kamwi, J., & Mbidzo, M. (2022). Impact of land use and land cover changes on landscape structure in the dry lands of Southern Africa: A case of the Zambezi Region, Namibia. GeoJournal, 87, 87–98.

Kamwi, J., Chirwa, P., Manda, S., Graz, P., & Kätsch, C. (2015). Livelihoods, land use and land cover change in the Zambezi Region, Namibia. Population and Environment, 37, 207–230.

Kamwi, J., Cho, M., Kätsch, C., Manda, S., Graz, F., & Chirwa, P. (2018). Assessing the spatial drivers of land use and land cover change in the protected and communal areas of the Zambezi region Namibia. Land, 7(4), 131.

Kamwi, J., Endjala, M., & Siyambongo, N. (2020). Dependency of rural communities on non-timber forest products in the dry lands of southern Africa: A case of Mukwe Constituency, Kavango East Region, Namibia. Trees, Forests and People, 2, 100022.

Kaoma, H., & Shackleton, C. (2014). Collection of urban tree products by households in poorer residential areas of three South African towns. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 13(2), 244–252.

Kasimba, S., Motswagole, B., Covic, N., & Claasen, N. (2018). Household access to traditional and indigenous foods positively associated with food security and dietary diversity in Botswana. Public Health Nutrition, 21, 1200–1208.

Kazembe, L., Nickanor, N., & Crush, J. (2022a). Food insecurity, dietary patterns, and Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) in Windhoek, Namibia. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition, 17(3), 425–444.

Kazembe, L., Crush, J. & Nickanor, N. (2022b). Food clusters, food security and the urban food system of northern Namibia (HCP Discussion Paper No. 55). Hungry Cities Partnership.

Kazungu, M., Zhunusova, E., Yang, A., Kabwe, G., Gumbo, D., & Günter, S. (2020). Forest use strategies and their determinants among rural households in the Miombo Woodlands of the Copperbelt Province Zambia. Forest Policy and Economics, 111, 102078.

Kroll, F., Swart, E., Annan, R., Thow, A., Neves, D., Apprey, C., Aduku, L., Agyapiong, N., Moubarac, J.-C., Du Toit<, A., et al. (2021). Mapping obesogenic food environments in South Africa and Ghana: Correlations and contradictions. In J. Crush & Z. Si (Eds.), Urban food deserts: Perspectives from the global South (pp. 91–122). MDPI.

Maroyi, A., & Cheikhyoussef, A. (2017). Traditional knowledge of wild edible fruits in southern Africa: Comparative use patterns in Namibia and Zimbabwe. Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge, 16(3), 385–392.

McLain, R., Hurley, P., Emery, M., & Poe, M. (2014). Gathering “wild” food in the city: Rethinking the role of foraging in urban ecosystem planning and management. Local Environment, 19(2), 220–240.

Mollee, E., Pouliot, M., & McDonald, M. (2017). Into the urban wild: Collection of wild urban plants for food and medicine in Kampala, Uganda. Land Use Policy, 63, 67–77.

Mulwa, C., & Visser, M. (2020). Farm diversification as an adaptation strategy to climatic shocks and implications for food security in northern Namibia. World Development, 129, 104906.

Musaba, E., & Sheehama, E. (2009). The socio-economic factors influencing harvesting of Eembe (Berchemia discolor) wild fruits by communal households in the Ohangwena region Namibia. Namibia Development Journal, 1(2), 1–12.

Mushabati, L., Kahaka, G., & Cheikhyoussef, A. (2015). Namibian leafy vegetables: From traditional to scientific knowledge, current status and applications. In C. Chinsembu (Ed.), Indigenous knowledge of Namibia (pp. 157–168). University of Namibia Press.

Nangulah, S., & Nickanor, N. (2005). Northern gateway: Cross border migration between Namibia and Angola (SAMP Migration Policy Series No. 38). Southern African Migration Program.

Nantanga, K., & Amakali, T. (2020). Diversification of mopane caterpillars (Gonimbrasia belina) edible forms for improved livelihoods and food security. Journal of Arid Environments, 177(3), 1094148.

Nickanor, N., Kazembe, L., Crush, J. &. Wagner, J. (2017). The supermarket revolution and food security in Namibia (AFSUN Urban Food Security Series No. 26). African Food Security Urban Network.

Ngome, P., Shackleton, C., Degrande, A., & Tieguhong, J. (2017). Addressing constraints in promoting wild edible plants’ utilization in household nutrition: Case of the Congo Basin forest area. Agriculture & Food Security, 6(1), 20.

Ngome, P., Shackleton, C., Degrande, A., Nossi, J., & Ngome, F. (2019). Assessing household food insecurity experience in the context of deforestation in Cameroon. Food Policy, 84, 57–65.

Nickanor, N., & Kazembe, L. (2016). Increasing levels of urban malnutrition with rapid urbanization in informal settlements of Katutura, Windhoek: Neighbourhood differentials and the effect of socio-economic disadvantage. World Health & Population, 16(3), 5–21.

Nickanor, N., Kazembe, L., & Crush, J. (2022). Food insecurity, food sourcing and food coping strategies in the OOO urban corridor, Namibia. In L. Riley & J. Crush (Eds.), Transforming urban food systems in secondary cities in Africa (pp. 163–185). Palgrave Macmillan.

NSA (2014). Regional profile for Oshana: Population and housing census. Namibia Statistics Agency.

Okeyo, D., Kandjengo, L., & Kashea, M. (2015). Harvesting and consumption of the giant African bullfrog, a delicacy in northern Namibia. In C. Chinsembu (Ed.), Indigenous knowledge of Namibia (pp. 205–218). University of Namibia Press.

Paumgarten, F., Locatelli, B., & Witkowski, E. (2018). Wild foods: Safety net or poverty trap? A South African case study. Human Ecology, 46(2), 183–195.

Powell, B., Thilsted, S., Ickowitz, A., Termote, C., Sunderland, T., & Herforth, A. (2015). Improving diets with wild and cultivated biodiversity from across the landscape. Food Security, 7(3), 535–554.

Rasmussen, L., Fagan, M., Ickowitz, A., Wood, S., Kennedy, G., Powell, G., Baudron, F., Gergel, F., Jung, S., Smithwick, E., et al. (2020). Forest pattern, not just amount, influences dietary quality in five African countries. Global Food Security, 25, 100331.

Reardon, T., Tschirley, D., Liverpool-Tasie, L., Awokuse, T., Fanzo, J., Minten, B., Vos, R., Dolislager, M., Sauer, C., Vargas, C., et al. (2021). The processed food revolution in African food systems and the double burden of malnutrition. Global Food Security, 28, 100466.

Sardeshpande, M., & Shackleton, C. (2020a). Fruits of the veld: Ecological and socioeconomic patterns of natural resource use across South Africa. Human Ecology, 48, 665–677.

Sardeshpande, M., & Shackleton, C. (2020b). Urban foraging: Land management policy, perspectives, and potential. Plos One, 15(4), e0230693.

Shackleton, C., & Shackleton, S. (2004). The importance of non-timber forest products in rural livelihood security and as safety nets: A review of evidence from South Africa. South African Journal of Science, 100(11–12), 658–664.

Shackleton, C., Hurley, P., Dahlberg, A., Emery, M., & Nagendra, H. (2017). Urban foraging: A ubiquitous human practice overlooked by urban planners, policy and research. Sustainability, 9(10), 1884.

Sneyd, L. (2013). Wild food, prices, diets and development: Sustainability and food security in urban Cameroon. Sustainability, 5(11), 4728–4759.

Sneyd, L. (2015). Zoning in: The contributions of buyam–sellams to constructing Cameroon’s wild food zone. Geoforum, 59, 73–86.

Sneyd, L. (2016). Wild food consumption and urban food security. In J. Crush & J. Battersby (Eds.), Rapid urbanisation, urban food deserts and food security in Africa (pp. 143–155). Springer.

Steyn, N., & Mchiza, Z. (2014). Obesity and the nutrition transition in sub-Saharan Africa. Annals of New York Academy of Sciences, 1311, 88–101.

Thomas, B. (2013). Sustainable harvesting and trading of mopane worms (Imbrasia belina) in Northern Namibia: An experience from the Uukwaluudhi area. International Journal of Environmental Studies, 70(4), 494–502.

Wingate, V., Phin, S., & Kuhn, N. (2016). Mapping decadal land cover changes in the woodlands of north eastern Namibia from 1975 to 2014 using the Landsat Satellite archived data. Remote Sensing, 8(8), 681.

WHO (2016). Namibia: State of the nation’s health. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation.

Zinyama, L., Matiza, T., & Campbell, D. (1990). The use of wild foods during periods of food shortage in rural Zimbabwe. Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 24(4), 251–265.

Funding

The research for this paper was funded by SSHRC Grant No. 435-2016-1636 and the analysis by SSHRC Grant No. 895-2021-1004. Open access funding provided by University of the Western Cape.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nickanor, N.M., Kazembe, L.N. & Crush, J.S. Wild and Indigenous Foods (WIF) and Urban Food Security in Northern Namibia. Urban Forum 35, 101–120 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-023-09487-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-023-09487-x