Structured Abstract

Objectives

Current policies for older patients do not adequately address the barriers to effective implementation of optimal care models in New Zealand, partly due to differences in patient definitions and the in-patient pathway they should follow through hospital. This research aims to: (a) synthesise a definition of a complex older patient; (b) identify and explore primary and secondary health measures; and (c) identify the primary components of a care model suitable for a tertiary hospital in the midland region of the North Island of New Zealand.

Method

This mixed-methods study utilised a convergence model, in which qualitative and quantitative data were investigated separately and then combined for interpretation. Semi-structured interviews (n=11) were analysed using a general inductive method of enquiry to develop key codes, categories and themes. Univariate data analysis was employed using six years of routinely collected data of patients admitted to the emergency department and inpatient units (n=261,773) of the tertiary hospital.

Results

A definition of a complex older patient was determined that incorporates chronic conditions, comorbidities and iatrogenic complications, functional decline, activities of daily living, case fatality, mortality, hospital length of stay, hospital costs, discharge destination, hospital readmission and emergency department revisit and age – not necessarily over 65 years old. Well-performing geriatric care models were found to include patient-centred care, frequent medical review, early rehabilitation, early discharge planning, a prepared environment and multidisciplinary teams.

Conclusions

The findings of this New Zealand study increase understanding of acute geriatric care for complex older patients by filling a gap in policies and strategies, identifying potential components of an optimal care model and defining a complex geriatric patient.

Implications for Public Health

The findings of this study present actionable opportunities for clinicians, managers, academics and policymakers to better understand a complex older patient in New Zealand, with significant relevance also for international geriatric care and to establish an effective acute geriatric care model that leads to beneficial health outcomes and provides safeguard mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As populations age and mortality rates reduce, the numbers of people with multiple comorbidities, disability and frailty increase. According to Meulenbroeks et al. (2021), "…the concept of geriatric syndrome encapsulates an older person's vulnerability associated with ageing and comorbidity". While early definitions of the geriatric syndrome experienced by older – predominantly frail older people are connected to intermittent episodes linked to subsequent functional decline (Flacker 2003), more recently, it has been viewed as conditions that accumulate to develop non-specific multisystem impairments and phenomenology (Meulenbroeks et al. 2021). Accordingly, the comorbidities, chronic and iatrogenic conditions associated with geriatric syndrome are now linked more strongly with frailty, poorer health outcomes and mortality (Inouye et al. 2007).

Hospitalisation is a significant event for people of all ages, but it holds particular importance for older people. This group may face age-related changes that elevate their risk of adverse events during in-patient care. Consequently, geriatric care models have been designed specifically to mitigate such risks, aiming to decrease the length of hospital stays and the frequency of readmissions for older people. Tailored care models for those over 65 years of age have become a valuable approach to enhance the well-being of older patients (Landefeld 2003; Boockvar 2020). While the successful implementation of interventions such as Acute Care for Elders (ACE) is considered best practice for obtaining favourable patient-centred outcomes (Bakker et al. 2011; Fox et al. 2012; Baztán et al. 2009; Ijadi 2022), current policies do not adequately address the barriers to effective implementation of such models in New Zealand due to differences in the clinical characteristics, mortality and admission rates (Yu et al. 2021).

The New Zealand healthcare system has experienced significant transformation over the last 30 years, marking a period of considerable evolution within the sector. Such structural changes have significantly influenced the organisation of funding and delivery of health services (Laugesen 2017; Goodyear-Smith and Ashton 2019), with the intention to improve health outcomes and increase efficiency. To address the ageing population trend and increased demand for health services in New Zealand, the Ministry of Health (MOH) (MinistryofHealth. 2016)released the Healthy Ageing Strategy in 2016, with the ultimate vision of older people living well, ageing well and having a respectful end of life. The MOH (2016) subsequently reported significant progress in the programme's first two years (MinistryofHealth. 2016). Nevertheless, there is significant room for improvement due to a suboptimal match between the care model policies and the characteristics of patients who require geriatric care. To enable further system-wide improvement, a more transparent, accurate and formal definition of complex acute geriatric patients is required that considers the specifics of different groups of the New Zealand population to guide the identification of primary components of optimal care interventions, as well as issues and complications in patient pathways (Laugesen 2017).

This study utilised a mixed-methods design for triangulation of data to gain a deeper understanding of geriatric care models for complex older patients by combining the advantages of qualitative and quantitative approaches. The research objectives included: (a) Synthesis of a complex older patient definition (thematic and univariate analysis); (b) Exploration of primary and secondary health measures (thematic and univariate analysis); and (c) Identification of the primary components of the care model at a tertiary hospital in the North Island of New Zealand (thematic analysis).

Materials and Methods

Ethics

This study obtained ethics approval from Health New Zealand as the participating facility (270,721-ltr-UHEC). It was approved, designed and implemented in accordance with the guidelines of the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee (UAHPEC3423) and the University of Waikato Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC2021#04).

Participants, Recruitment and Sampling

Potential participants were contacted by email through the hospital’s Older Person Health and Rehabilitation service administrator and invited to discuss the study with the researchers. Informed consent was collected using an official consent form at recruitment and immediately prior to participation. The details of all participants were anonymised. Participants were purposively sampled across five stakeholder groups: general physicians, geriatricians, senior nurses and allied health workers as well as senior administrators. The inclusion criteria targeted senior health professionals involved in providing and delivering geriatric care who could provide informed consent. The study design required a minimum sample size of 11 senior health professionals, which was expected to be sufficient to reach thematic and data saturation in interviews based on a homogeneous and small population (Francis et al. 2010). The interpretive systemic framework uses a knowledge-based method to deeply understand how organisations work. It does this by looking at different perspectives from various backgrounds, which helps in deciding how to collect a range of opinions effectively.

Study Instruments

The interview guide contained a uniform introduction of the interviewers, eight primary questions and a further 14 subset questions addressing the study's research objectives. The interview questions were intended to elicit the interviewees' overall experiences and reflect on their experiences and expectations of geriatric care models. The interview guide received feedback from academics and other senior health professionals, was validated in the design process and was piloted twice before interviewing the participants. Interviews were designed to take between 45 to 60 min. The interview schedule is provided in Supplementary Interview Schedule S1. After the introduction, study terms, including geriatric syndrome, were described to participants in each interview, as well as examples of medical areas. Geriatric syndrome was defined as an older (most often 65 +) patient with at least one comorbidity or iatrogenic complication (Bakker et al. 2011; Fox et al. 2012; Baztán et al. 2009; Ellis et al. 2011). Comorbidities were defined as chronic conditions such as hypertension, ischemic heart disease, diabetes, arthritis, heart failure, depression, chronic kidney disease, osteoporosis, Alzheimer's disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, atrial fibrillation, cancer, asthma and stroke. Iatrogenic complications included falls, pressure ulcers, delirium, adverse drug reactions and anaphylaxis.

For definition purposes, non-complex medicine included the Acute Medical Unit (AMU) or medical assessment unit and the three internal medicine wards and the three Older People Rehabilitation (OPR) wards represented a complex. Patients in OPR wards have a mixture of medical conditions and comorbidities and they are not necessarily over 65 years old, whereas the internal medicine wards tended to receive patients with single conditions. The study first defines complex patients based on data triangulation and interviews. It then explores functional decline, comorbidities and iatrogenic complexities within primary and secondary healthcare settings, including costs, length of stay, readmissions, case fatality and mortality. These results are later compared against the perspectives of the interview participants on ideal policies to develop well-substantiated geriatric care solutions.

Data Collection

To collect narratives and interpretations of acute geriatric models and implementations of such care models, 11 independent semi-structured interviews were conducted by the authors A.I.M and J.B.A for each stakeholder group between November and December 2021. Each interview followed the primary questions presented in the interview schedule. Follow-up questions were either selected from the interview schedule or asked in response to participant experiences. The interviewer permitted silences throughout the interview and, with caution, drew on their own clinical and administrative knowledge to prompt detail. All interviews were recorded, manually transcribed verbatim and shared amongst the interviewees for reflection, feedback and approval. For the quantitative data analysis, six years of routinely collected data (from January 2016 to November 2021) on ED and hospital admissions were provided to the researchers via an encrypted iron key, matched with other datasets, including InterRAI assessment data (Wellens et al. 2012) and Australian Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (AR-DRGs) and then de-identified using a codebook by data analysis staff at the hospital. The age limit was not restricted to 65 + years, so the age eligibility criterion that might disproportionately exclude older people could also be examined. Outpatient care patients who were in paediatric units, patients with missing medical records data and those who were hospitalised outside the study time range were excluded.

Analysis

This mixed-methods study utilised a convergence model, in which qualitative and quantitative data were investigated separately and then combined and compared for interpretation and clarification (Creswell et al. 2011). To ensure the rigor of our qualitative analysis, interviews were analysed using a reflexive and interpretive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2019) and the Framework Method (Ritchie et al. 2013). An inductive-deductive method was adopted to confirm the conclusion, whereby the conclusion (theory) of the inductive phase is also used as a starting point for the deductive phase. This approach allowed themes to emerge organically from the experiences reported by participants and also deductively from the Normalization Process Theory (NPT) (May and Finch 2009), which was used as the primary framework guiding the analysis. This dual-origin methodology ensured a comprehensive exploration of the data, capturing both anticipated and novel insights. The coding process of the thematic analysis was not conducted in a linear fashion but rather iteratively. This non-linear approach facilitated a dynamic interaction with the data, allowing for the refinement of codes and themes as new insights were uncovered. The coding process involved the researchers familiarising themselves with the interviews, generating initial codes based on the literature review, which provided a solid theoretical grounding for the analysis, generating the initial themes and sub-themes, a step crucial for establishing a preliminary understanding of the data, reviewing the initial themes and sub-themes, to ensure that they accurately represented the data, finalising and defining final themes and codes and reporting the final thematic analysis. This iterative cycle of review and refinement played a key role in ensuring the thematic analysis was both comprehensive and reflective of the data. To ensure reliability, all codes and themes developed and categorised were discussed, refined and agreed upon by members of the research team. This collaborative approach endeavoured to ensure that the analysis was robust, credible and validated by multiple perspectives within the research team. Coding, themes and sub-themes cross-referencing and indexing were assisted and completed using QSR NVivo (Version 1.5.2, QSR International) (QSR 2016). The use of NVivo facilitated a systematic and organized approach to data management and analysis, ensuring that the process was transparent and replicable. Exploring the narratives involved the iterative steps of defining codes and themes and data reduction, which allowed for the distillation of complex data into coherent and meaningful patterns, thereby enhancing the analytical rigor of the study.

Simple descriptive and univariate analyses of patients in OPR and non-OPR wards were used to describe the basic features of the data. Pearson's chi-squared test compared the characteristics of patients who went through the OPR wards. Differences in patient characteristics between those who did and did not go through the OPR wards were examined using Student's t-test or Wilcoxon rank–sum test. Missing values within the data were handled by removing the episode from patient records within the entire sample. All analyses were conducted using R programming language version 4.2.0 (R Foundation). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Interview and Thematic Analysis Results

On average, participant interviews lasted 38.50 min, ranging from 29.30 to 63.28 min. Participants were predominantly female (n = 7, 63.7%) and came from various backgrounds, as summarised in Table 1. Three primary themes were identified from the thematic analysis of the interviews undertaken to present an explanation of the initial definition of a complex older patient, explore primary and secondary healthcare measures and investigate principal components of geriatric care models suitable for a tertiary hospital in the North Island of New Zealand. The coding structures and specific quotations accompanying each theme are available in Supplementary Table S1.

Theme #1: Initial Complex Patient Definition

These one arose from 14 codes which were collapsed into two categories both defining a definition for complex patients. An essential aspect of older patient care is knowing the characteristics of patients presenting to the hospital. Although various studies have focused on determining an acute frail older person's functional capability (Fox et al. 2012; Ellis et al. 2011), they use different definitions considering variables such as quality of life and socio-economic status. The Agency for Healthcare and Quality (AHRQ) defines complex patients as "…persons with two or more chronic conditions where each condition may influence the care of the other condition…" (Loeb et al. 2016). According to the literature (Webster et al. 2019), "…defining patient complexity as morbidity alone is inadequate; such models neglect conditions that are not included in formal disease classifications…". Definitions were discussed with participants to identify complex medical issues in older people presenting at the hospital.

"…(When talking about complexity) I think the older frail patients with acute issues and complex social situations, then typical demented patients with acute physical illness that might be delirious. Also, (when talking about complexity) patients with unclear diagnoses that may need complex interventions. The OPR average patients are older, …much older… and compared with the patients in other medical wards, they possibly most likely have baseline dysfunction. I think that is one of the features of geriatric patients. However, most of our patients are frail and dependent at baseline. It is possible that age is not the disability and poor baseline function level will be the core feature of all patients in OPR wards…" (Interviewee #3 – Senior Health Professional)

A complex older patient is likely to have multiple chronic conditions, including comorbidities and iatrogenic complications such as ischemic heart disease, diabetes, arthritis, depression, chronic kidney disease, osteoporosis, Alzheimer's disease, pressure ulcers, delirium and adverse drug reactions (Baztán et al. 2009; Ellis et al. 2011). Participants also focused on the difference between acute and sub-acute complexities.

"An acute condition is one that typically arises suddenly without warning and requires immediate attention, such as an acute myocardial infarction. A subacute condition would be a patient with underlying ischemic heart disease with worsening chest pain over a period of time. Older patients' presentations tend to be subacute for multiple reasons. So, a younger patient with an 'acute abdomen' problem, such as gallbladder disease, may seek immediate attention, an older patient, especially one who is frail, may not seek attention for five days." (Interviewee #4 – Senior Health Professional)

While participants' perspectives on the definition of an acute complex patient aligned with findings from other studies (Ruiz et al. 2015; Zwijsen et al. 2016), participants, when prompted, had different perspectives about the age stratification that sees only patients aged over 65 years old admitted to a specialist geriatric ward. The primary reason behind such mixed remarks on age may be differences in mortality and hospital admission rates between Māori (the indigenous people of New Zealand), Pacific and non-Māori (Yu et al. 2021). Although age is a primary factor in establishing a geriatric care model, it is unsuitable for patients at the aforementioned tertiary hospital.

"…(complex patients can be) medical patients who have multiple issues; they are not truly rehab and they are more complicated with multiple comorbidities, (coming from) all sorts of ages and often have social issues as well. There is some neurology in there, too. They (inpatient wards) do get younger people with chronic health issues, who present like an older person but are actually 48 and are not eligible for some funding because of their age and have poor social situations and that is what is going to grow into OPR ward. They can be acutely unwell, but they might have hazardous medication use, they might be at risk of falling, along with social issues such as no enduring power of attorney…" (Interviewee #1 – Operations/Medical Director)

Hence, an initial definition of the acute complex older patient can be extracted based on chronic conditions, comorbidities and iatrogenic complications, but the patient will not necessarily be aged over 65 years. However, this definition is only preliminary and additional primary and secondary health measures must be analysed.

Theme #2: Primary and Secondary Healthcare Measures

Theme two arose from 19 codes which were collapsed into four categories on the primary and secondary components and measures related to complex older patients. A critical element in devising efficient strategies for meeting the care requirements of the most vulnerable populations is identifying the characteristics of patients seeking hospital care. Previous studies considered age a significant risk factor for increased vulnerability (Bakker et al. 2011; Fox et al. 2012). However, in Theme #1, an important interpretation extracted from the participants' narratives was that age is not necessarily a predictor of complexity and frailty can occur in younger age groups within the geriatric cohort (patients older than 40). Participants were asked to dive deeper into the definition of complexity by discussing primary and secondary healthcare measures in terms of the complex and non-complex medical areas at the tertiary hospital. Functional decline, comorbidities and iatrogenic complications were addressed with the participants, emphasizing the need for primary healthcare interventions. The participants emphasized the importance of understanding the perspective from which the patient's defining complexity attributes are assessed. Since primary and secondary measures predominantly focus on functional health outcomes, utilising these measures at the same time as a composite measure should be considered when optimising patient care processes. A consensus was also reached regarding functional decline, reflecting a uniform stance on the subject among participants.

"… They are different to me than the frequent presenters in that the older presenter is going to have a downward trajectory; they are going to decline, it just matters the timing and cause (cancer versus worsening fragility)" (Interviewee #4 – Senior Health Professional)

Functional decline is characterised by a reduction in the capacity for self-care, leading to diminished functional autonomy, heightened disability and complications in performing activities of daily living. These issues are directly associated with adverse health outcomes (Ryan et al. 2015). The presence of comorbidities predicts future functional decline, particularly in patients exhibiting a high degree of complexity and severity in their conditions. Discussions among participants emphasized the critical need to develop targeted interventions and healthcare systems. These are especially vital for older patients who present with significant disease severity and a more extensive array of major health concerns, underscoring the importance of tailored care strategies for individuals with comorbidities and iatrogenic complexities.

"OPR houses more complex older patients with geriatric syndromes such as those suffering cognitive impairment or more subacute long-term problems like wound care (i.e., decubitus ulceration)"; "The OPR patient would usually suffer from some more underlying complex issues, we keep getting back to patients inflicted by acute medical disorders complicated by dementia, social situations. Alternatively, underlying advanced frailty"; "…numbers of older people admitted to the hospital with specific chief complaints and admitting diagnosis…"; "…numbers of patients screening positively on applicable screen(s) (e.g., delirium, functional decline, falls and abuse)…" (Interviewee #4 – Senior Health Professional)

The hospital is not always the best location for older patients. Geriatric patients may experience significant deterioration in function and strength, as well as an increased risk of iatrogenic complexities (Fox et al. 2012; Fox et al. 2013), while in hospital. More extended hospital stays result in higher costs and extra burdens on patients, their families and the healthcare system. These are the main reasons why length of stay has been debated since the 1970s (Buttigieg et al. 2018). Evidence from multiple studies shows that prolonged stays in acute hospitals increase the risk of cognitive and physical decline in geriatric patients and increased risk of hospital-acquired infections, disrupting patient flow (Fox et al. 2012; Baztán et al. 2009; Fox et al. 2013). Participants had similar concerns about reducing the length of hospital stay, recognising the importance of this target for the Ministry of Health (Tenbensel et al. 2017).

"Time of decision to discharge in OPR is 6 or 10 hours, but in the AMAU, that can be as short as 15 minutes. So, we should not put people who are short stay into a different environment." (Interviewee #8 – Operations/Medical Director)

While length of stay is one of the most commonly used measures for quality of care, other closely linked elements used to monitor hospital performance are ED revisits and number of hospital admissions (Rachoin et al. 2020; Lingsma et al. 2018). The mechanism underpinning these measures and their relationship should be analysed and clearly understood as they reflect the quality of care. When prompted, participants made the same link between readmissions and ED revisits and their relationship with length of stay:"…the number of representations would give you a good idea…". Participants agreed that the significant relationship between reducing length of stay and readmissions is a key performance indicator.

"I think the big ones that the hospital always looks at are the length of stay and readmissions. Because, if we can cut down the readmissions, we can reduce the demand on the health system and cost for that patient journey." (Interviewee #10 – Senior Health Professional)

In addition to the length of stay, the other target almost always mentioned by participants was hospital costs. As mentioned by Interviewee #5 – Senior Health Professional; "…in inpatient wards, most often our big thing was to look at readmission rates, length of stay, the cost that was involved with that patient…". Analysing narratives on hospital costs shows that hospitals have at least two incentives to reduce readmission rates and length of stay. While the primary concern is improving the functional outcomes, avoiding the sizable financial penalties imposed by higher numbers of readmissions, revisits and length of stay is also important.

"Even though our length of stay is still a cost associated with that person coming in, you take in the nursing time, the doctor's time, the admin time, the HCA time and the products we have used. So, I think everywhere there is definitely a cost associated with every person that comes in the door. But it is how we manage that and try to make it as some lesser cost, but it is not at the same time compromising their well-being and their safety, which can often come into it as well…" (Interviewee #5 – Senior Health Professional)

One of the critical objectives of planning strategies for older patients' rehabilitation and care is returning older people to their previous living conditions, maintaining independence and quality of life and thus preventing early transfer to an aged care facility. Consistent with prior research (Fox et al. 2012; Baztán et al. 2009), participants, when prompted, recognised several factors influencing the determination of patients' discharge destinations. These factors include age, extended hospital stay, comorbidities, lower functional status before admission and reduced mobility during hospitalisation. A clear consensus was evident among participants on the critical need for a comprehensive understanding of the patient's intended post-discharge destination to facilitate effective discharge planning.

"For the older person, you look at if they can return home; if they come from home, can they return to the previous level of functioning? If they come from a rest home and are in the hospital, they might be in hospital-level care and can return to the rest home level of care." (Interviewee #3 – Senior Health Professional)

As mentioned by the narratives, case fatality for "all causes of mortality" is another crucial predictor when measuring patients' health outcomes against key system performance indicators. The overall mortality rate among the geriatric population admitted with multiple comorbidities is higher than among the adult trauma population and patients older than 74 years suffering from traumatic injuries and comorbidities are at a higher risk of mortality (Hashmi et al. 2014).

"…the standard you look at is mobility, morbidity and mortality (death rate). So those are the common parameters (when) we look at if you would like to do a project, such as length of stay, mortality and return their previous level function." (Interviewee #3 – Senior Health Professional)

Ultimately, based on Theme #1 and #2, a complex acute older patient at the aforementioned tertiary hospital in New Zealand can be qualitatively defined in terms of chronic conditions, comorbidities and iatrogenic complications, functional decline, activities of daily living, case fatality, mortality, hospital length of stay, hospital costs, discharge destination, hospital readmission and emergency department revisits and not necessarily aged over 65 years. This qualitative definition can shed more light on definitions of complex and non-complex geriatric patients when benchmarking patients according to historical data.

Theme #3: Components of a Suitable Geriatric Care Model

Theme three arose from 28 codes which were collapsed into five categories on the primary components of geriatric care model. Several geriatric care models have been developed recently with a focus on improving health outcomes, level of functioning and quality of life (Landefeld 2003; Boockvar 2020), including Acute Care for Elders – ACE (Landefeld et al. 1995), Hospitalized Elder Life Program – Help (Inouye et al. 1999)and Geriatric Evaluation and Management Units – GEMU (Ellis and Langhorne 2004). The most popular model is the ACE programme, which applies to different settings, including ED and inpatient units. An acute older person model of care can be defined based on the following components: "…patient-centred care; activities to prevent decline in Activity of Daily Living (ADL), mobility, continence and cognition; frequent medical review; activities to minimise the adverse effects of treatments on older people' functioning; early rehabilitation; the participation of physical and occupational therapists to initiate rehabilitation; early discharge planning; activities to facilitate return to the community; and prepared environment; environmental modifications to facilitate physical and cognitive functioning…" (Baztán et al. 2009). Participants, when prompted, had similar perspectives on the primary components of geriatric care models. Almost all participants agreed that thorough assessment of patients during admission and clinical decision-making guided by patient standards and values aare the main factors in tailoring care to frail older patients with comorbidities and chronic conditions.

"If the aim is to get them back into a safe environment, you may recognize that you need extra support. Whether it is supplied through the needs assessment process or just the whole network of resources that come with that — whether it is shower systems, highlighting the importance of ensuring these people get Meals on Wheels, or whether it is something else, or whether it is carer relief, no matter what the issues are — you might identify them and get them there" (Interviewee #8 – Operations/Medical Director)

One of the prerequisites of providing optimal patient-centred care is having a prepared environment. Prepared environments and associated factors are linked with better quality of life, well-being, life satisfaction and self-rated health for geriatrics. A prepared environment for older people incorporates modifications to facilitate physical and cognitive functioning. While almost the same notions were described by the participants, for them, a significant aspect of the concept of a prepared environment was patients being in an "environment of their choice where they feel comfortable" and where they "do not have that loss of dignity and disability in the hospital". From the participants' perspective, a prepared environment means modifying the environment for physical and cognitive functioning and maintenance and creating an environment to maintain and improve quality of life, well-being and life satisfaction.

"Well, my immediate thoughts are that being closer to home is in the patient's interests. I would not want to be stranded at a hospital; I would want to be close to my family, able to visit my family, or be home for a part of the day. Seeing that family, the longer I am in the hospital, the more it potentially disables me. It is not an environment that meets my needs." "So, it has got to be in an environment where they feel just at ease, just as at ease as the staff member, especially when they might find themselves in a physical space which is embarrassing for them, compared to how they are normally able to function." (Interviewee #1 – Operations/Medical Director)

While frequent medical review is most often associated with actions to minimise the adverse effects of treatments on functional outcomes (Malone et al. 2014), participants, when prompted, usually viewed frequent medical review as involving primary health measures such as assessing pre-existing living arrangements. Participants also expressed the importance of risk measures, triggers and assessment scores when conducting a medical review.

"We have many people that fall at home and need some sort of assessment treatment or not necessarily rehab, but definitely assessment treatment, to figure out why they fell and what are the consequences after they fell. We did a frailty score electronically and that will trigger off risk around nutrition, falls and pressure injuries and all of that will cascade together based on the first trigger point, which was frailty." (Interviewee #9 – Senior Health Professional)

The effect of early rehabilitation utilising physical interventions with acutely hospitalised patients has already been examined in several systematic reviews (Kosse et al. 2013). These interventions, such as early physical exercise, were mentioned a couple of times by participants, not only in relation to early rehabilitation but also with a focus on early discharge planning to return the patient to their preferred living environment.

"Other considerations for me when deciding if the patient can be discharged home from the ED prior to discharge are as follows: Does the patient have cognitive deficits that could impede his/her recovery and home-based management? Is the patient able to ambulate safely? Does the patient understand and have access to any new prescriptions?" (Interviewee #4 – Senior Health Professional)

According to previous studies (Fox et al. 2013), "early discharge planning is defined by interventions introduced during the acute phase of an illness or injury to facilitate transition of care back to the community as soon as the acute event is stabilised". While participants had the same perspective on early discharge planning, an essential factor in their view was"understanding where and how the patient is going to be discharged" and the types of social and living support they are going to receive after being discharged. An interesting point of view on early discharge planning was looking at the discharge destination and hospital length of stay as essential predictors of readmission risk.

" So, I think there are different ways of measuring the types of patients in the ward and then the journey can be looked at by where they have been discharged to. So, if you look at where they are discharged to and the length of stay, that is where you can model what patients we can prevent from coming in or getting out quicker" (Interviewee #6 – Senior Health Professional)

Furthermore, effective and efficient multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) through different layers of care are considered as success factors in older patient care (Ellis and Sevdalis 2019). Participants believed creating, maintaining and coordinating high-performing MDTs should be one of the main priorities in older people care.

"It is about how we can have a coordinated MDT approach that is not based on 'I am a physio, you are an occupational therapist and you are a nurse and we all have our specialities.' So, all three of us have to go and see this patient. What is it that the patient needs?" "What I have seen work well is where there is really good coordination among individuals who come together to make plans, including the patient and the families" (Interviewee #9 – Senior Health Professional)

An in-depth thematic analysis of participants' narratives shows that a well-substantiated geriatric care solution for the aforementioned tertiary hospital in New Zealand should incorporate patient-centred care, frequent medical review, early rehabilitation, early discharge planning, prepared environment and multidisciplinary teams. Additionally, patients' prioritisation based on complex and non-complex definitions should be based on the explanations in Theme #1 and Theme #2.

Data Analysis Results

Six years of de-identified Emergency Department (ED) and hospital admission data (January 2016 to November 2021) from a tertiary hospital in the North Island of New Zealand were analysed with a focus on understanding the dynamics within geriatric patient care, though not exclusively limited to patients aged 65 and above. Among the 261,773 referrals, the demographic breakdown reveals significant insights into the patient population, emphasizing the diversity and complexity of cases managed by the hospital, with particular attention to those admitted to OPR wards. In presenting the findings of this study, we specifically highlight data that aligns with the qualitative analysis, drawing clear connections between the numerical trends and understanding of geriatric care models. This approach ensures a coherent narrative that illustrates the complications of managing complex patient needs, especially within specialized wards like the OPR. While a summary of descriptive statistics is presented in Table 2, Supplementary Material Table S2 provides a comprehensive overview of the descriptive statistics to compare the specialised (OPR) ward with other wards.

The analysis identified that 2,170 patients (including complex OPR and non-complex OPR) were admitted to OPR wards, with a majority being female (53.7%) and of New Zealand European descent (67.2%). This demographic information is crucial as it informs the qualitative exploration of healthcare accessibility and equity, particularly for Māori and Pacific populations whose representation in specialized care appears disproportionately low (14.3%). According to the data, Māori constitute 25.7% of the patient population across all wards, indicating a significant underrepresentation in specialized care. The LOS data, especially the higher averages in the complex OPR ward, alongside the highest resource consumption as indicated by Australian Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (AR-DRGs) metrics (46.6%), serve as evidence supporting the qualitative findings on the intensive nature of geriatric care and rehabilitation. This underscores the need for specialized, resource-intensive care models like the OPR, which are designed to address the needs of older patients. The significant percentage of patients in the complex OPR ward with high Patient Clinical Complexity Levels (PCCL) and the extensive use of InteRAI assessment instruments (98.7% of older patients assessed with at least four instruments) demonstrate the complex care and thorough assessment required for geriatric patients. These statistics are directly relevant to the qualitative outcomes on the complexity of geriatric care and the necessity of assessment tools to tailor patient-centred care plans.

Qualitative and Quantitave Data Triangulation

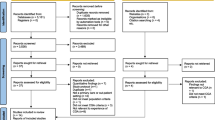

To further analyse the findings of the qualitative study and cross-validate the outcomes, we employed a standard triangulation framework and test those findings against a large dataset of empirical data. This research was conceptualised using a mixed-methods triangulation design to combine qualitative and quantitative data sources, with an equal status sequential design, resulting in the convergence of the qualitative and quantitative methods as presented in Fig. 1. The primary advantage of the triangulation design stems from its ability to offer a more comprehensive understanding by integrating multiple perspectives. This approach not only enriches the research findings but also enhances the validity of the results by cross-verifying data through different lenses. Following this, it is noteworthy that compared to the sequential explanatory and exploratory designs, the triangulation design is characterised by its efficient progression through the research phases. This approach often results in well-validated and substantiated findings as it mitigates the limitations inherent in one methodology by employing the strengths of another (Creswell et al. 2003). Merging data sources and research methods can also be beneficial in allowing a greater depth of understanding and a more holistic view of the phenomenon under study. Nevertheless, there are two notable challenges: first, it demands a considerable amount of effort, as well as expertise, to collect and analyse two separate sets of data simultaneously; and second, the technical complexity of comparing different quantitative and qualitative data sets can be challenging, particularly when the results from both sets fail to align.

The quantitative analysis reveals demographic, clinical and outcome variations across different wards, with a particular focus on the OPR wards. This analysis is instrumental in painting a detailed picture of the geriatric patient profile and, when combined with qualitative insights, offers a deep dive into the complexities of caring for this demographic. Specifically:

-

Age and Comorbidities: The mean age and availability of multiple comorbidities in the OPR wards highlight the geriatric patient's vulnerability and the complexity of their care needs. This aligns with the qualitative theme that geriatric care goes beyond just the age factor, focusing instead on the complicated nature of their health conditions.

-

Length of Stay (LOS): The higher-than-average LOS in OPR wards underscores the qualitative narratives around the extensive care and rehabilitation geriatric patients require, further complicated by their comorbidities.

-

Readmission Rates: descriptive statistics on readmissions within one, three- and six-months post-discharge from OPR wards illustrate the ongoing health challenges faced by geriatric patients, showing the qualitative outcomes on the need for robust post-discharge support and care continuity.

-

Costs: The analysis of hospital costs associated with geriatric care in OPR wards provides an illustration of the resource-intensive nature of managing complex geriatric patients, resonating with the thematic analysis findings that advocate for efficient, patient-centred care models to mitigate these costs.

Leveraging both qualitative insights and quantitative analyses, a refined definition of a geriatric patient within the context of this study, is characterized by: (a) multiple comorbidities; (b) a higher-than-average Length of Stay (LOS) on previous admissions; (c) historically more frequent readmissions within 3 and 6 months, underscoring the ongoing health management needs beyond initial discharge; (d) Patient Clinical Complexity Level (PCCL) > 2; (e) Changes in Health, End-stage disease, Signs and Symptoms Scale (CHESS) > 3, (f) Disease Instability and Variability Evaluation Tool (DIVERT) > 3, (g) with patients DRGs associated most with acute and subacute endocarditis, major cardiovascular procedures with complications and rehabilitation.

Discussion and Limitations

Using in-depth interviews with senior health professionals involved in the delivery of geriatric care at a tertiary hospital in the North Island of New Zealand, along with a data analysis based on patients referred to the hospital over six years, this study synthesised a definition of complexity allowing for the specificity of New Zealand geriatric patients and identified drivers of effective acute geriatric care. Based on the thematic analysis and data analysis, a complex acute geriatric patient may be defined by individual characteristics and complexities (chronic conditions, comorbidities, iatrogenic complications, ethnicity and age – not necessarily over 65), functionality (functional decline and activities of daily living), clinical scales and outcomes (PCCL, interRAI assessment and sub-assessments, case fatality and mortality), system interactions (length of stay, costs, hospital readmission and emergency department revisits) and support systems(discharge destination). While this outcome is consistent with previous research (Kumlin et al. 2020; Ruiz et al. 2016), age stratification of patients over 65 was not a predictor in this study. According to the Healthcare Resource Group (HRG) within the English National Health Service (NHS), which is similar to Australian Refined Diagnosis Related Groups, a complex older patient is defined as someone having two or more major diagnoses with no significant procedure recorded and whose age is greater than 69 years (Ruiz et al. 2016). The primary reason for excluding age stratification can be explained using the cohort morbidity hypothesis.

The cohort morbidity hypothesis was developed to explain the fact that increasing life expectancy at older ages is a result of reductions in chronic diseases and inflammation over time. According to Yon and Crimmins (Yon and Crimmins 2014), despite recent reductions in infant mortality rates in both Māori and non-Māori populations in New Zealand, the historical trend of relatively high mortality continues for Māori older persons. Although mortality from heart disease is decreasing worldwide, the slower decline in rates of cardiovascular death among Māori compared to non-Māori is a major public health concern (Ajwani et al. 2003). According to the Ministry of Health (MOH) New Zealand (King 2000), the Māori population lags far behind the non-Māori population on all indicators of health and well-being. This is one of the main reasons Māori patients only 40 years old can sometimes present with the complexities and comorbidities of a geriatric patient, as defined by previous literature. These findings point to a need to identify additional predictors for the complex patient definition between Māori and non-Māori, which is why this study explored the complexity definition before analysing the drivers of an effective care model.

Furthermore, based on the definition of complexity and in-depth analysis of narratives, a well-substantiated geriatric care solution should incorporate patient-centred care, frequent medical review, early rehabilitation, early discharge planning, prepared environment and multidisciplinary teams. This outcome is congruent with previous systematic reviews of geriatric acute care and the components of successful interventions and initiatives (Bakker et al. 2011; Fox et al. 2012; Baztán et al. 2009; Ellis et al. 2011). Consistent with other reports (Mudge et al. 2021), the study participants recognised the central importance of geriatric care principles, including comprehensive risk assessment linked to integrated multidisciplinary care planning and how early rehabilitation and prepared care environments can enhance the delivery of geriatric care. Hence, policymakers should consider these initiatives and plan actionable opportunities when establishing an acute geriatric care model to support evidence-based and optimal care environments.

Even though this study has accomplished the stated research intentions, some limitations still exist. Due to lack of information regarding social support within hospital administrative data, the data analysis did not examine the relationship between social support, comorbidity and long-term mortality in hospitalised geriatric patients. This study only conducted simple univariate analysis and presented descriptive statistics. Hence, a more in-depth analysis is recommended using regression models to assess the association between complex patients and factors such as length of stay, the number of admissions, readmission and mortality. Moreover, the participants in this study were knowledgeable senior advocates for older person care. It is therefore acknowledged they may not recognise barriers and enablers experienced by other staff, decision-makers and patients. However, the outcomes of the study are congruent with barriers identified in other research exploring the perspectives of geriatric acute care consumers, their caregivers and staff (Bridges and Flatley 2010). A larger thematic analysis could be undertaken incorporating more types of stakeholders, including different levels of staff, policy and decision-makers, as well as consumers, specifically patients and caregivers. Ultimately, the larger thematic analysis could also undertake a larger number of participants in order to allow the research study to generalise their findings.

Expanding on the recommendations of this study for enhancing geriatric care, it becomes clear that a phased approach is essential for addressing the multifaceted nature of geriatric patient management. In the short-term, prioritising the enhancement of patient-centred care is fundamental. This involves not only the integration of multidisciplinary teams, which brings together professionals from various specialties to provide comprehensive care, but also a strong emphasis on early rehabilitation and discharge planning. Such efforts are aimed at shortening the length of stays and minimising the rates of readmission, thereby directly impacting patient well-being and system efficiency. Furthermore, these teams should leverage patient and caregiver feedback to continuously refine care processes, ensuring that they are responsive and tailored to the needs of geriatric patients. Transitioning into medium-term strategies, the focus shifts towards building the capacity of the systems to manage the complexities of geriatric care more effectively. This encompasses the development and implementation of specialised training programmes for healthcare professionals, designed to enhance their understanding and skills in geriatric care. Moreover, incorporating technology and telehealth solutions can play a pivotal role in this phase, enabling ongoing patient management and support beyond the traditional healthcare settings. Such technologies can facilitate remote monitoring, teleconsultations and virtual rehabilitation sessions, offering a continuum of care that is both accessible and efficient.

Looking towards the long-term horizon, the recommendations are on systemic changes that lay the foundation for sustainable, high-quality geriatric care. This includes policy reforms that recognise and address the unique needs of the ageing population, as well as substantial investments in healthcare infrastructure. The establishment of specialised geriatric care units and the adoption of national guidelines are critical steps in ensuring that care delivery is consistent and adheres to the highest standards across different regions and healthcare systems. Additionally, increased funding for geriatric research is vital for advancing the understanding of ageing-related health issues and developing innovative care models that can effectively respond to these challenges. By implementing these short, medium and long-term recommendations, healthcare systems can achieve a holistic and integrated approach to geriatric care. Such an approach not only aligns with the findings of this study but also addresses the broader public health objective of improving the quality of life for older people, ensuring they receive the care and support they need to lead fulfilling lives.

Conclusion

This study aimed to gain a broader understanding of acute geriatric care for complex older patients by identifying potential components of an optimal care model and synthesising a definition of a complex older patient to address a gap in current strategies. Our findings indicate actionable opportunities for clinicians, managers, academics and policymakers to better understand New Zealand's complex patients and establish an effective acute geriatric care model. Prioritising the establishment of an effective model can create beneficial outcomes and provide safeguard mechanisms such as age-friendly quality and better health outcomes. Future research is required to explore, evaluate and establish appropriate solutions for complex geriatric patients. Given the increasing dependence of this frail population on the healthcare system, providing care for geriatric patients may become a crucial issue.

References

Ajwani, S., Blakely, T., Robson, B., Tobias, M., Bonne, M. J. WMo. H., & Otago, Uo. (2003). Decades of disparity: ethnic mortality trends in New Zealand 1980–1999 (p. 130)

Bridges, J., & Flatley, M. (2010). Meyer JJIjons. Older People’s and Relatives’ Experiences in Acute Care Settings: Systematic Review and Synthesis of Qualitative Studies., 47(1), 89–107.

Buttigieg, S. C., Abela, L., & Pace, A. (2018). Variables affecting hospital length of stay: A scoping review. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 32(3), 463–493.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health., 11(4), 589–597.

Baztán, J. J., Suárez-García, F. M., López-Arrieta, J., Rodríguez-Mañas, L., & Rodríguez-Artalejo, F. (2009). Effectiveness of acute geriatric units on functional decline, living at home and case fatality among older patients admitted to hospital for acute medical disorders: Meta-analysis. BMJ (clinical Research Ed)., 338, b50.

Bakker, F. C., Robben, S. H., & Olde Rikkert, M. G. (2011). Effects of hospital-wide interventions to improve care for frail older inpatients: A systematic review. BMJ Quality and Safety, 20(8), 680–691.

Boockvar, K. S., Judon, K. M., Eimicke, J. P., Teresi, J. A., & Inouye, S. K. (2020 Oct). Hospital Elder Life Program in Long-Term Care (HELP-LTC): A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 68(10), 2329–2335. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16695, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32710658/. Epub 2020 Jul 25. PMID: 32710658; PMCID: PMC7718417.

Creswell, J. W., Klassen, A. C., Plano Clark, V. L., & Smith, K. C. (2011). Best practices for mixed methods research in the health sciences. National Institutes of Health., 2013, 541–545.

Creswell, J. W., Clark, V. L. P., Gutmann, M. L., & Hanson, WEJHommis. (2003). Research b. ADVANCED MIXED (p. 209)

Ellis, G., & Sevdalis, N. (2019). Understanding and improving multidisciplinary team working in geriatric medicine. Age and Ageing., 48(4), 498–505.

Ellis, G., Whitehead, M. A., Robinson, D., O’Neill, D., & Langhorne, P. (2011). Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital: Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ, 343, d6553.

Ellis, G., & Langhorne, P. (2004). Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older hospital patients. British Medical Bulletin., 71, 45–59.

Flacker, J. M. (2003 Apr). What is a geriatric syndrome anyway? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 51(4), 574–6. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51174.x, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12657087/. PMID: 12657087.

Fox, M. T., Persaud, M., Maimets, I., O’Brien, K., Brooks, D., Tregunno, D., et al. (2012). Effectiveness of acute geriatric unit care using acute care for elders components: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 60(12), 2237–2245.

Francis, J. J., Johnston, M., Robertson, C., Glidewell, L., Entwistle, V., Eccles, M. P., et al. (2010). What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychology & Health, 25(10), 1229–1245.

Fox, M. T., Persaud, M., Maimets, I., Brooks, D., O’Brien, K., & Tregunno, D. (2013b). Effectiveness of early discharge planning in acutely ill or injured hospitalized older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatrics., 13(1), 70.

Fox, M. T., Sidani, S., Persaud, M., Tregunno, D., Maimets, I., Brooks, D., et al. (2013a). Acute care for elders components of acute geriatric unit care: Systematic descriptive review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 61(6), 939–946.

Goodyear-Smith, F., & Ashton, T. (2019). New Zealand health system: Universalism struggles with persisting inequities. Lancet (london, England)., 394(10196), 432–442.

Hashmi, A., Ibrahim-Zada, I., Rhee, P., Aziz, H., Fain, M. J., Friese, R. S., et al. (2014). Predictors of mortality in geriatric trauma patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery., 76(3), 894–901.

Inouye, S. K., Studenski, S., Tinetti, M. E., & Kuchel, G. A. (2007). Geriatric Syndromes: Clinical. Research and Policy Implications of a Core Geriatric Concept., 55(5), 780–791.

Ijadi Maghsoodi, A., Pavlov, V., Rouse, P., Walker, C. G., & Parsons, M. (2022 Nov). Efficacy of acute care pathways for older patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Ageing, 19(4), 1571–1585. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-022-00743-w, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36506680/. PMID: 36506680; PMCID: PMC9729482.

Inouye, S. K., Bogardus, S. T., Jr., Charpentier, P. A., Leo-Summers, L., Acampora, D., Holford, T. R., et al. (1999). A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. The New England Journal of Medicine., 340(9), 669–676.

Kosse, N. M., Dutmer, A. L., Dasenbrock, L., & Bauer, J. M. (2013). Lamoth CJJBg. Effectiveness and Feasibility of Early Physical Rehabilitation Programs for Geriatric Hospitalized Patients: A Systematic Review., 13(1), 1–16.

King, A. J. WMo. H. (2000). The New Zealand Health Strategy.

Kumlin, M., Berg, G. V., Kvigne, K., & Hellesø, R. (2020). Elderly patients with complex health problems in the care trajectory: A qualitative case study. BMC Health Services Research., 20(1), 595.

Landefeld, C. S. (2003). Improving health care for older persons. Annals of Internal Medicine., 139(5 Pt 2), 421–424.

Laugesen, M. J. (2017). Book Review: Robert H. Blank, New Zealand Health Policy: A Comparative Study (Auckland: Oxford University Press, 1994), pp. ix, 166, $34.95. Political Science, 48(1), 112–3.

Loeb, D. F., Bayliss, E. A., Candrian, C., deGruy, F. V., & Binswanger, I. A. (2016). Primary care providers’ experiences caring for complex patients in primary care: A qualitative study. BMC Family Practice., 17(1), 34.

Lingsma, H. F., Bottle, A., Middleton, S., Kievit, J., Steyerberg, E. W., & de Marang-van Mheen, P. J. (2018). Evaluation of hospital outcomes: the relation between length-of-stay, readmission and mortality in a large international administrative database. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 116.

Landefeld, C. S., Palmer, R. M., Kresevic, D. M., Fortinsky, R. H., & Kowal, J. (1995). A Randomized Trial of Care in a Hospital Medical Unit Especially Designed to Improve the Functional Outcomes of Acutely Ill Older Patients. New Engl J Med., 332(20), 1338–1344.

Meulenbroeks, I., Schroeder, L., & Epp, J. (2021). Bridging the Gap: A Mixed Methods Study Investigating Caregiver Integration for People with Geriatric Syndrome. International Journal of Integrated Care, 21(1), 14.

MinistryofHealth. (2016). Healthy Ageing Strategy. Ministry of Health.

May, C., & Finch, T. (2009). Implementing, Embedding and Integrating Practices: An Outline of Normalization Process Theory. Sociology, 43(3), 535–554.

Mudge, A. M., Young, A., McRae, P., Graham, F., Whiting, E., & Hubbard, R. E. (2021). Qualitative analysis of challenges and enablers to providing age friendly hospital care in an Australian health system. BMC Geriatrics., 21(1), 147.

Malone, M. L., Capezuti, E. A., & Palmer, R. M. (2014). Acute Care for Elders.

QSR International Pty Ltd. (2016). NVivo qualitative data analysis Software (11 ed).

Ruiz, M., Bottle, A., Long, S., & Aylin, P. (2016). Multi-Morbidity in Hospitalised Older Patients: Who Are the Complex Elderly? PLoS ONE, 10(12), e0145372.

Ruiz, M., Bottle, A., Long, S., & Aylin, P. (2015). Multi-Morbidity in Hospitalised Older Patients: Who Are the Complex Elderly? PLoS One, 10(12), e0145372-e.

Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Nicholls, C. M., & Ormston, R. (2013). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. sage.

Rachoin, J. S., Aplin, K. S., Gandhi, S., Kupersmith, E., & Cerceo, E. (2020). Impact of Length of Stay on Readmission in Hospitalized Patients. Cureus, 12(9), e10669-e.

Ryan, A., Wallace, E., O’Hara, P., & Smith, S. M. (2015). Multimorbidity and functional decline in community-dwelling adults: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 13, 168-.

Tenbensel, T., Chalmers, L., Jones, P., Appleton-Dyer, S., Walton, L., & Ameratunga, S. (2017). New Zealand’s emergency department target – did it reduce ED length of stay and if so, how and when? BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 678.

Wellens, N. I., Flamaing, J., Moons, P., Deschodt, M., Boonen, S., & Milisen, K. (2012). Translation and adaption of the interRAI suite to local requirements in Belgian hospitals. J BMC Geriatrics., 12(1), 1–11.

Webster, F., Rice, K., Bhattacharyya, O., Katz, J., Oosenbrug, E., & Upshur, R. (2019). The mismeasurement of complexity: Provider narratives of patients with complex needs in primary care settings. International Journal for Equity in Health., 18(1), 107.

Yu, D., Zhao, Z., Osuagwu, U. L., Pickering, K., Baker, J., Cutfield, R., et al. (2021). Ethnic differences in mortality and hospital admission rates between Māori, Pacific and European New Zealanders with type 2 diabetes between 1994 and 2018: A retrospective, population-based, longitudinal cohort study. The Lancet Global Health., 9(2), e209–e217.

Yon, Y., & Crimmins, E. M. (2014). Cohort Morbidity Hypothesis: Health Inequalities of Older Māori and non-Māori in New Zealand. New Zealand Population Review., 40, 63–83.

Zwijsen, S. A., Nieuwenhuizen, N. M., Maarsingh, O. R., Depla, M. F. I. A., & Hertogh, C. M. P. M. (2016). Disentangling the concept of “the complex older patient” in general practice: a qualitative study. BMC family practice, 17, 64-.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants who kindly provided their valuable time to be interviewed for this study. We would also like to thank Graham Guy for his assistance in the fieldwork stage of the research.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept: Ijadi Maghsoodi, Barlow-Armstrong, Pavlov, Parsons, Rouse, Walker. Study design: Ijadi Maghsoodi, Barlow-Armstrong, Parsons, Rouse, Pavlov, Walker. Interviews: Ijadi Maghsoodi, Barlow-Armstrong. Statistical Analysis: Ijadi Maghsoodi. Write-up: Ijadi Maghsoodi. Data extraction and interpretation: Ijadi Maghsoodi. Data analysis: Ijadi Maghsoodi. Manuscript preparation: Ijadi Maghsoodi, Barlow-Armstrong, Pavlov, Parsons, Rouse, Walker. Critical manuscript revision: Ijadi Maghsoodi, Barlow-Armstrong, Pavlov, Parsons, Rouse, Walker.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare (a) no financial support for the submitted work from anyone other than their employer or affiliated institute; (b) no financial relationships with commercial entities that might have an interest in the submitted work; (c) no spouses, partners, or children with relationships with commercial entities that might have an interest in the submitted work; and (d) no non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

Sponsor’s Role

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ijadi Maghsoodi, A., Barlow-Armstrong, J., Pavlov, V. et al. What Makes Effective Acute Geriatric Care? - A mixed Methods Study From Aotearoa New Zealand. Ageing Int (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-024-09568-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-024-09568-7