Abstract

Better home care and home care technologies are no longer requested solely by nonimmigrant older adults but also by members of the fast-growing older adult immigrant population. However, limited attention has been given to this issue, or to the use of technology in meeting the needs of aging populations. The objective of this review is to map existing knowledge of older adult immigrants' use of information and communication technologies for home care service published in scientific literature from 2014 to 2020. Twelve studies met the established eligibility criteria in a systematic literature search. The results showed older adult immigrants faced similar barriers, which were independent of their ethnic backgrounds but related to their backgrounds as immigrants including lower socioeconomic status, low language proficiency, and comparatively lower levels of social inclusion. Technology use could be facilitated if older adult immigrants received culturally-tailored products and support from family members and from society. The results imply that the included studies do not address or integrate cultural preferences in the development of information and communication technology for home care services. Caregivers might provide an opportunity to bridge gaps between older immigrants' cultural preferences and technology design. This specific research field would also benefit from greater interest in the development of novel methodologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With globalization and increased mobility across national borders, the number of migrants worldwide has increased from 173 million in 2000 to 272 million in 2019 (McAuliffe & Khadria, 2019). The surge of international migrants has had a profound influence on the demonographies and social structures of the host societies. It is well-known that the percentage of older adults is increasing worldwide, faster than any other age group (Goldstein, 2009; Lutz et al., 2008; United Nations, 2017). Less discussed are older immigrants who represent a growing share of the migrant population. The longitudinal data from the United Nations and from previous studies suggest that although most international immigrants are still of working age, the percentage of older adult immigrants of the whole immigrant population has reached 11% in middle-income countries and 13% in the higher-income countries (Bekteshi & Kang, 2020; Derose et al., 2007; Hansen, 2014; IOM, 2017; UN DESA, 2019; Warnes et al., 2004). An older adult immigrant, for the purposes of this study, describes a foreign-born person who either moved to another country at the age of retirement or moved to another country as a working adult then approached later life in the host societies (Castles et al., 2014; Hooyman & Kiyak, 2014; Warnes et al., 2004). Older immigrants are a heterogeneous group in numerous aspects, including immigration history, socioeconomic status, culture, religion, and life course (Barth et al., 2014; Moberg et al., 2016; Treas & Gubernskaya, 2016; Warnes et al., 2004). This heterogeneity creates additional complexity for researchers in capturing variation within and between ethnic groups (Hooyman & Kiyak, 2014). Compared with nonimmigrant older adults, older adult immigrants are often more vulnerable and lack health resources that create new challenges in the healthcare system (Arora et al., 2018; Franchi et al., 2016; Lum & Vanderaa, 2010; Ruspini, 2009). It is necessary to identify relevant themes that represent older immigrants’ circumstances across different ethnicities and cultures. Despite heterogeneity in older immigrant groups, this review is motivated by creating new knowledge from similarities and differences within and between different groups and individual experiences in an attempt to understand the challenges of aging as immigrants (Östlund, 2005).

Home care service is becoming a more and more promising approach in offering support to older adults at home and continues to act as an agency for health resources (Liu et al., 2017; Miner et al., 2018). With the increasing number of older immigrants, there has been a growing discussion about better home care for diverse older populations (Ciobanu et al., 2017; Fret et al., 2020; Moon et al., 2020). In this review, home care service is defined as the care service performed by professional caregivers outside the family to support healthy aging at home, which encompasses personal care, domestic aids, and complex nursing care (Genet et al., 2011; Sixsmith et al., 2014). The physical boundary of people's homes can no longer define the working environment of home care, which has extended to include remote health interventions and supports delivered over the Internet, such as e-Health, smart home technology, and home monitoring systems (Demiris et al., 2004; Lindberg et al., 2013; Lindeman et al., 2020).

Numerous reports have suggested information and communication technology (ICT) can play a role in supporting the “aging-in-place” policy, which enables older adults to live independent, active, and meaningful later lives, at home, for as long as possible (Agree, 2014; King & Workman, 2006; Lindeman et al., 2020; Selwyn et al., 2003; Vasunilashorn et al., 2012; Walsh & Callan, 2011). Regardless of comprehensive digitalization, the adoption of technology that enables and supports home-based care among native older adults and older immigrants is overlooked (Tatara et al., 2016; Zeissig et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2018). A recent study by Mitchell et al. (2019) suggested that cultural factors may be determining factors in the use of technology. However, there has not been much research aimed at tailoring culturally-relevant designs. The global network society broadly described by Manuel Castells has not yet been researched with regard to aging populations and older immigrants, nor has their use of ICT-based technologies in meeting their needs for care and service (Castells, 2000, 2002; Chen et al., 2020; Mercer et al., 2015).

One of the most urgent issues being discussed today regarding how to meet the needs of growing older populations is the technology adoption and use. The recent development of ICT in the realm of home care service demonstrates an encouraging potential for older adults to be included and considered in future development and research agendas (Cisotto & Pupolin, 2018; Hasan & Linger, 2016; Mercer et al., 2015). Additionally, the implementation of ICT also increases the efficiency of home care services delivery and communications (Anderson & Perrin, 2017; Cisotto & Pupolin, 2018; Wiklund-Axelsson et al., 2013).

Objectives

This review aims to map the barriers and facilitators to the adoption and use of ICT in homecare services and disparities between the nonimmigrant older adults and older immigrants from contemporary literature on ICT use in home care services that help identify gaps in current literature and guide future studies.

What kinds of ICT-based technologies do older immigrants use in home care services?

-

(1)

What are the barriers and facilitators for older immigrants to using ICT-based technology?

-

(2)

Which disparities are described between nonimmigrant older adults and older immigrants in the use of technology in the included articles?

Methods

Search Strategy

The systematic literature was conducted according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews (PRISMA) (Moher et al., 2009). Six relevant databases were searched, including Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, Medline, EBSCOhost Library-Information Science & Technology, and EBSCOhost-Ergonomics.

The authors determined specific keywords and keyword groups iteratively by conducting several trial searches. The keywords searched were divided into four groups: (1) "old", "elderly" and synonyms; (2) ICT-based technology (e.g., e-Health, monitoring systems) and broader terms (e.g., technology and gerontechnology); (3) "home care," “aging in place” and terms related to home care; (4) “immigrant”, “migration” and other synonyms that indicate migration background. We searched for articles that matched at least one keyword of each above-mentioned group in the title, abstract, or keywords. As this is a review of published material, ethical approval was not necessary.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Articles that met with the following criteria were included: (1) published in peer-reviewed journals; (2) published between January 1st, 2014, and May 20th, 2020; (3) written in English. Publications were excluded if they were: (1) published in non-peer-reviewed sources; (2) review articles, book chapters, and conference proceedings; (3) not focused on older adults living at home (4) on individuals not receiving home care services. Articles written in languages other than English were excluded because of the additional efforts and expenses involved in search strategy and translation.

Articles were also excluded if they related to older adults suffering from cognitive impairments in consideration of the difficulties of using ICT while cognitively impaired. When discussing technology used for cognitively impaired older adults, scholars tend to focus more on the use of technology to find solutions to support family caregivers and reduce burdens of care (Boots et al., 2014; Brodaty & Donkin, 2009). Furthermore, the use and influence of ICT among cognitively-impaired older adults must be examined closely, together with disease etiology and degree of impairment.

Data Extraction

Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the first author removed duplicate manuscripts by title, then screened the titles and abstracts of the remaining eligible articles. The second and the third authors reviewed this process and results of the inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure all eligible articles were screened according to established criteria. The first author read through the identified articles in full text to generate relevant findings in each article that fit the purpose of this review. The results were reviewed and discussed by all authors to reach a consensus on creating themes and categorizing relevant findings into different themes via an iterative process. All authors discussed and summarized relevant information into these themes, which were aimed supporting further analysis and comparison of evidence. Study characteristics and the participants involved were retrieved and organized into a standardized table that included the author’s name, year of publication, and study samples (e.g., age, ethnicity, size, and location). Furthermore, we classified the study design, data collection method, and the main findings related to the purpose of this review into Table 1.

Quality Appraisal of Papers

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018, was used to assess the quality of the included articles (Hong et al., 2018). MMAT is designed to appraise empirical studies included in systematic reviews containing qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method studies. The MMAT checklist permits the researcher to evaluate and describe the methodological quality of the five most common categories of empirical research designs: Qualitative, Quantitative-randomized control trial, Quantitative non-randomized control trial, Quantitative descriptive, and Mixed-methods (Pluye et al., 2009). The MMAT checklist is a widely used quality appraisal tool for systematic literature reviews, which has proven both efficient and user-friendly (Pace et al., 2012). Instead of counting for overall scores, MMAT focuses on details of each criterion that better informs the quality of included studies that allows the authors to exclude the articles with the lowest methodological quality or compare the high-quality articles with the lower quality articles (Hong et al., 2018). The MMAT checklist contains two screening questions and five quality criteria categories for different empirical designs. The quality of the included studies was evaluated by answering each question in the relevant categories as “Yes” (Y), “No” (N), or “Can’t tell” (N/A) (see supplementary tables).

Results

Characteristics of Included Studies

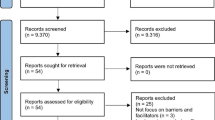

The initial search of titles, abstracts, and author’s keywords resulted in a collection of 1,177 articles from databases and 5 articles from personal libraries (Fig. 1). After removing duplicates, we reviewed the titles and abstracts of the remaining 667 records and excluded 629 articles according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. Thirty-eight articles were selected and their texts were reviewed in full. Subsequently, 26 articles were excluded. Finally, 12 articles were selected to be analyzed in this study.

Of the 12 included articles, nine (75%) studies were conducted in the United States, two (16.67%) studies were conducted in Australia, and one (8.3%) was from the United Kingdom. Among the total (12) articles, six (50%) applied quantitative methods using questionnaires or surveys (5/6) (Arcury et al., 2017, 2018; Chang et al., 2015; Hames et al., 2016; Walters et al., 2017; Yamazaki et al., 2017) and secondary data collected through a previous study (1/6) (Hames et al., 2016). Five articles applied qualitative study methods, using interviews, focus group interviews, and observations (Berridge et al., 2019; Chung et al., 2017a, b; Goodall et al., 2014; Li et al., 2018; Millard et al., 2018). Only one study employed a mixed method of sensor monitoring data and individual interviews (Chung et al., 2017a, b).

Content Analysis

Ethnicities of the Participants

Five studies were conducted exclusively on specific ethnic groups, among which four articles focused on East Asian older adults from China, Korea, and Japan living in the United States (Chung et al., 2017a, b; Li et al., 2018; Yamazaki et al., 2017). One was aimed at the Greek and Italian communities in Australia (Goodall et al., 2014). The other seven studies were conducted in ethnically diverse areas where the residents were comprised of African, Asian, Latino, White non-Latino, and other immigrant groups (Arcury et al., 2017, 2018; Chang et al., 2015; Hames et al., 2016; Millard et al., 2018; Walters et al., 2017). In this latter category, studies could investigate shared characteristics among selected communities related to socioeconomic status, education, health conditions, and health resources. Underlying cultural and ethnic differences often went underdiscussed.

Home Care Services

Although home care was the main inclusion criteria, in-home caregivers did not participate directly in any papers with the exception of one study (Millard et al., 2018). The subject of home care was embedded in studies as a contextual factor in the homes of older adults. The challenges of home care services were not the main focus of the included studies. Instead, the scholars focused on characteristics of the ethnic minority in the study, the technology itself, and the interaction between older adults and the relevant technology. Nonetheless, the articles documented the increase in the home care efficiency by improving health self-management (Arcury et al., 2017, 2018), increasing access to general and health-related information (Chang et al., 2015; Goodall et al., 2014; Li et al., 2018; Millard et al., 2018), assisting healthcare planning (Hames et al., 2016; Walters et al., 2017); and monitoring and risk prevention (Berridge et al., 2019; Chung et al., 2017a, b; Yamazaki et al., 2017).

Home care was introduced as a new approach to traditional family- and community-based care among immigrant families. Home care resources were insufficient among older immigrants residing in ethnicity-diverse low-income communities or rural areas, considering the cost and availability of services (Chung et al., 2017a, b; Goodall et al., 2014; Hames et al., 2016; Millard et al., 2018; Walters et al., 2017). Also, in many situations home care providers could not provide home care services that matched with the language preferences or cultures of older adults (Arcury et al., 2018; Chang et al., 2015; Chung et al., 2017a, b; Goodall et al., 2014; Li et al., 2018; Millard et al., 2018; Walters et al., 2017; Yamazaki et al., 2017).

ICT-based Technologies as a Part of Home Care

Older immigrants used two types of technologies in the included studies: unobtrusive technologies, including sensor-based home monitoring systems and personal emergency response systems (Berridge et al., 2019; Chung et al., 2017a, b; Hames et al., 2016; Yamazaki et al., 2017), and technologies that required more control and interaction, such as the digitalized self-health management tool, e-Health, and other communication tools (Arcury et al., 2017, 2018; Chang et al., 2015; Goodall et al., 2014; Li et al., 2018; Millard et al., 2018; Walters et al., 2017).

Some researchers aimed to find associations between demographic characteristics and technology acceptance and compared disparities between older immigrants and nonimmigrant older adults (Arcury et al., 2017, 2018; Chang et al., 2015; Li et al., 2018). Older immigrants with lower education levels were associated with less experience in using ICT-based technologies and with lacking digital literacy (Arcury et al., 2017, 2018; Chang et al., 2015). The low education level suggested insufficient language proficiency, which hindered communication and created additional barriers to digital healthcare resources (Arcury et al., 2017, 2018; Chang et al., 2015; Li et al., 2018). Disadvantageous economic status was related to the migration experience, which increased difficulties in obtaining new technologies (Arcury et al., 2017, 2018; Chang et al., 2015; Li et al., 2018).

Some studies explored older immigrant's behaviors while using new technologies (Berridge et al., 2019; Chung et al., 2017a, b; Goodall et al., 2014; Millard et al., 2018; Yamazaki et al., 2017). The researchers collected data from interactions between older adults and the relevant technologies and then interpreted the interaction and preferences from cultural, economic, and environmental perspectives. The article pointed out the critical role of meeting cultural preferences to improve perceived benefits and ease of use, which increased the acceptance rate of technology (Chung et al., 2017a, b). Berridge et al. (2019) investigated the influences of ethnicity and cultures in the adoption and discontinuation of technology over time among older adults from different ethnic backgrounds. Goodall et al. (2014) explored the information behaviors and digital technology use of older Italian and Greek immigrants, who lagged behind in adapting to the gathering of information online. Millard et al. (2018) demonstrated the beneficial potential of a culturally and socially appropriate learning environments in improving older immigrants' digital literacy, which enabled the use of the Internet for obtaining general and health-specific information. Older Japanese immigrants preferred to invest in health services and technologies that mitigated minor health conditions, which, in their belief, could reduce the possibility of developing more severe health problems (Yamazaki et al., 2017).

The rest of the studies focused on integrating new technology for the more efficient provision of home care services (Hames et al., 2016; Walters et al., 2017). Older participants validated the technology’s functionality, which proved its potential to be integrated into home care. Hames et al. (2016) showed that an age-adjusted socially- and medically-vulnerable map could support aging-in-place initiatives and further planning for different age cohorts in ethnically diverse retirement communities. Walters et al. (2017) demonstrated that a computer-aided self-risk appraisal system (Multi-dimensional Risk Appraisal for Older people, MRA-O) could provide valuable advice to local home care services in meeting the needs of older immigrants.

Shared Barriers to Using Technology for Home Care Services

Older immigrants shared some barriers in accessing technology as part of home care services. The first commonly mentioned barrier was low socioeconomic status. Many immigrants had been involved in low-paying industries with shorter careers than their nonimmigrant counterparts (Arcury et al., 2017, 2018; Chang et al., 2015; Chung et al., 2017b). The length of their careers had resulted in low social security benefits, which were not sufficient for acquiring home care services and technologies (Li et al., 2018; Yamazaki et al., 2017). The cost of acquiring and using technology became a significant barrier for older immigrants experiencing financial hardship (Arcury et al., 2017, 2018; Chang et al., 2015; Chung et al., 2017a, b; Goodall et al., 2014; Li et al., 2018; Millard et al., 2018).

Second, older adults usually had insufficient language proficiency in their host society, and in some cases, even suffered from mother-tongue illiteracy (Arcury et al., 2017, 2018; Chang et al., 2015; Chung et al., 2017a, b; Goodall et al., 2014; Li et al., 2018; Millard et al., 2018). These barriers impeded effective direct communication between older adults and healthcare professionals. Lacking language proficiency hindered the use of technology using an unfamiliar language and limited communication channels and forms (Arcury et al., 2017; Berridge et al., 2019; Chang et al., 2015; Chung et al., 2017a, b; Goodall et al., 2014; Millard et al., 2018; Walters et al., 2017).

Third, social integration was a significant barrier for older adults that limited the scope of social networking and their ability to seek information (Arcury et al., 2017, 2018; Chang et al., 2015; Goodall et al., 2014; Li et al., 2018). Older immigrants preferred to live in environments where residents shared the same cultures, languages, and experiences (Chung et al., 2017a, b; Goodall et al., 2014; Hames et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018; Yamazaki et al., 2017). However, this behavior decreased the possibility of receiving public information and increased the value of information shared within the community (Chang et al., 2015; Goodall et al., 2014; Li et al., 2018). In addition, it reduced the need to use ICT and participants were unmotivated to learn about new technology. It also decreased the presence of ethnic minorities in the participation of social activities (Chang et al., 2015; Goodall et al., 2014; Walters et al., 2017).

Shared Facilitators to Use Technology for Home Care Services

Facilitators encouraged older immigrants to use new technologies as part of home care services. The involvement of a family member was the most effective facilitator for older adults to start considering technology (Arcury et al., 2017; Berridge et al., 2019; Chang et al., 2015; Goodall et al., 2014). The participation of a family member or a familiar person could improve feelings of security and increase adoption rates, however, it did not lead to continuous use (Chang et al., 2015; Goodall et al., 2014). Older immigrants who did not have available family members, favored social learning occasions and training programs (Arcury et al., 2017; Chang et al., 2015; Goodall et al., 2014; Li et al., 2018; Millard et al., 2018).

Second, social and political support could improve the affordability and accessibility of ICT infrastructure and devices to older immigrants (Arcury et al., 2017; Chang et al., 2015; Chung et al., 2017a, b; Li et al., 2018; Millard et al., 2018). Policymakers played a distinct role in facilitating ICT accessibility by increasing investments in the construction of digital infrastructure and public facilities (e.g., libraries) (Arcury et al., 2017; Chang et al., 2015; Millard et al., 2018). Moreover, financial support could significantly mitigate concerns around the cost of obtaining new technology and maintenance (Arcury et al., 2017; Chang et al., 2015; Chung et al., 2017a, b; Li et al., 2018).

Third, studies showed that older immigrants expressed a greater willingness to use technology if the technology in question could be tailored to cultural preferences that fit their needs (Berridge et al., 2019; Chang et al., 2015; Chung et al., 2017a, b; Goodall et al., 2014; Millard et al., 2018; Walters et al., 2017; Yamazaki et al., 2017). Different ethnicities showed unique needs that were related to their cultural backgrounds and the particular context involved in using the relevant technology. For example, participants favored audio information over written information, which was related to the difficulty of reading foreign languages, or to visual impairments (Chang et al., 2015; Goodall et al., 2014; Walters et al., 2017). East Asian participants stated their preference for living independent lives with more privacy and dignity, which increased their favor toward using ambient assisted-living technologies such as sensor-based monitoring systems and personal emergency response systems (Berridge et al., 2019; Chung et al., 2017a, b; Yamazaki et al., 2017). Although some studies stressed difficulty in recruiting participants, the studies that focused on the specific daily challenges of specific ethnic groups experienced less stress in attracting and engaging older immigrants, even long-term participation was required (Chung et al., 2017a, b; Goodall et al., 2014; Li et al., 2018; Yamazaki et al., 2017).

The Disparities Between Nonimmigrant Older Adults and Older Immigrants

Five studies involved older immigrants from low-income communities or from rural areas. Older immigrants experienced more difficulties than the majority group in acquiring and using ICT technologies. Older immigrants in these communities had disadvantageous socioeconomic conditions and worse health conditions than the nonimmigrant older adults in the same area (Arcury et al., 2017, 2018; Chang et al., 2015; Goodall et al., 2014; Walters et al., 2017). Disparities in using ICT were significant within the low-income population in which access to technology and healthcare was countered by concerns over its cost and effectiveness(Arcury et al., 2017, 2018; Chang et al., 2015). Compared with older adults in the majority population, older immigrants had literacy difficulties in both their birth language and the language (English) of their host societies (Chang et al., 2015; Walters et al., 2017).

Older immigrants encountered more barriers in accessing necessary health information and showed insufficient abilities in using electronic self-management tools (Arcury et al., 2017, 2018). Compared with nonimmigrant older adults, older immigrants showed lower e-Health literacy that affected their motivation in using the available online health resources to gain knowledge of their health condition or to aid in solving their health problems. These results suggested that older adults in ethnic minority groups with low-income levels and poor education had higher likelihoods of having low digital and eHealth literacy, limiting their use of online resources.

On the other hand, immigration, per se, did not lead to difficulties in later lives. Affluent Japanese immigrants who lived in Hawaii would prioritize health conditions and independence over the cost of home care services and new technologies (Yamazaki et al., 2017). Their economic status supported the older Japanese population in this region to practice traditional social norms of elder care, exemplified by the highest health check-up frequency, the highest rate of primary care utilization, and a high willingness to pay (or have family members pay) additional money for home care services and new technologies, as compared to other ethnicities. It showcased a unique pattern among older immigrants who had enough resources to achieve superior health condition than other ethnicities in the area.

Discussion

Vulnerability of Immigrant Groups and the Social Integration Process

All included articles demonstrate the multiple difficulties of aging as an immigrant. The stated difficulties comply with the findings of migration studies that documented inherent vulnerabilities resulting from migration, related to language proficiency, socioeconomic status, and participation in public affairs (Angel et al., 2016; Derose et al., 2007). The situation often deteriorates with advancing age when immigrants become older and more dependent on the healthcare system. The factors influencing vulnerability are interrelated, and result in poor health conditions. For the purpose of reducing disparities in health, a practical approach would be to assist the integration of older immigrants into society by improving the degree of acculturation with constant and positive interactions. Social integration is a dynamic process that aims at reducing differences between immigrants and nonimmigrants, while different ethnicities model patterns and strategies under different social contexts (Berry, 2004). The acceptance of the host society is positively correlated with ICT use and with high utilization of the care system (Hansen, 2014; Zhao et al., 2018).

Language proficiency is the most common barrier to social integration (Arcury et al., 2017, 2018; Berridge et al., 2019; Chang et al., 2015; Chung et al., 2017a, b; Goodall et al., 2014; Li et al., 2018; Millard et al., 2018), which may go unaddressed over a long period of time and may increase the risk of social isolation (Chung et al., 2017a, b; Goodall et al., 2014; Li et al., 2018). Limited language proficiency not only restricts the number of available information sources but also becomes a barrier to the diffusion of innovation over time (Liu et al., 2017; Wejnert, 2002). Li et al. (2018) describe how language could influence everyday life, lower social service usage, and undermine self-esteem, which causes difficulties and barriers to interacting with society. Stakeholders could proactively emphasize improving language proficiency by providing affordable language courses focusing on language for daily use. In addition to the language courses, scholars have suggested that “support personnel” with bicultural or bilingual backgrounds significantly promote older immigrants’ use of care services and ICT (Green et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2017). Support personnel help older immigrants bridge language gaps, increase their confidence in handling complicated affairs, and mitigate the stress from the environment and from using new technologies. Support personnel in the literature covered in this review includes volunteers, friends, relatives, and children, while home caregivers also show great potential in assuming these responsibilities. Thus, stakeholders can consider addressing low engagement in health systems and low levels of ICT use by providing attractive job opportunities to improve caregiver diversity.

Socioeconomic status is an essential indicator that plays a major role in shaping the experiences of acculturation and aging in the host society. For instance, wealthier older Japanese immigrants show more flexibility toward using home care services and technology (Yamazaki et al., 2017). Among wealthier older immigrants, decision-making regarding consumption is more dependent on perceived utility and function (Yamazaki et al., 2017). This result is in line with previous literature that suggests the wealth of the family at the moment of migration determines life trajectories in host societies and available resources in later life (Hao, 2004). It also decreases the differences between immigrants and nonimmigrant older adults regarding consumption choices and reduces social integration difficulties (Hao, 2007). However, older immigrants of lower economic status end up coping with limited information, limited social networks, insufficient health resources and with living on the “wrong” side of the digital divide (Chesser et al., 2016; Reneland-Forsman, 2018; Wolfson et al., 2017). Public investments in infrastructure and public facilities could mitigate the cost of using new technologies that help to increase ICT use. Training courses designed to improve digital literacy are always popular among older adults if a course is affordable and delivered in appropriate languages (Ferreira et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018; Millard et al., 2018). These courses could help older immigrants attain confidence, improve their perceived benefits on using new technology, and reduce anxiety toward technology (Demiris et al., 2004; Holttum, 2016).

ICT-based Technology Used by Older Immigrants

These findings suggest that older immigrants favor unobtrusive technology because this type of technology is easy to use and less intrusive, (Chung et al., 2017a, b; Hames et al., 2016; Yamazaki et al., 2017) and does not require advanced digital skills to function properly. In addition, instead of relying solely on the older immigrants themselves, home care providers or other trusted persons can assume the responsibility of handling the data and information. Concerns associated with these types of technologies are the initial cost of acquisition and ongoing cost of maintenance, and privacy issues (Chung et al., 2017a, b; Chung et al., 2017a, b; Yamazaki et al., 2017). Another disadvantage of this type of technology is their limited function, which focuses merely on monitoring a hazardous situation at its current stage of development. Another type of technology discussed is digitalized health information and communication, which is housed mainly on the Internet. Although the cost of using the system is low, it requires users to attain a certain level of language proficiency, digital literacy, and health literacy. This technology has more functions that could provide comprehensive health information and remote supports, but it is also more sophisticated and more difficult for older immigrants to use.

The ICT-based technologies mentioned in the included studies are neither developed directly from the needs of older immigrants, nor do they consider cultural preference. Thus, the process of adopting new technology requires older immigrants to adapt to technology that might not fit their preferences. Although it is evident in some cases that older immigrants could benefit from new technology and home care, these options fail to encompass the growing heterogeneity among older adults belonging to different cultural backgrounds and subjects them to unique but significant challenges. The next step ICT development could consider including the targeted older adults in design methodology, which could contribute to reducing barriers to adoption.

Implications for Improving Technology Use in the Home Care Setting

“Aging in place” requires social and political support to enable the home environment to become a suitable place for older adults to stay as long as they wish (Genet et al., 2011; Hooyman & Kiyak, 2014). In the included studies, home care has become an indispensable part of the process that helps ICT function as designed. However, home care providers did not participate directly in the research program or in ICT development (Chung et al., 2017a, b; Hames et al., 2016). One reason could be related to the research emphases of the studies, which focus more on the feasibility of the technology, the users’ experiences, and the users’ characteristics. It may also imply that there is an insufficient provision of home care services for ethnic minorities. Also, although home caregivers are using technology daily and interact with the care recipients directly, the role of home caregivers concerning technological innovation is often invisible, and the potential of utilizing their professional experience is neglected.

Participants in the included studies stressed the expectation of having culturally appropriate technologies that can better meet their demands and preferences (Chang et al., 2015; Goodall et al., 2014; Millard et al., 2018; Walters et al., 2017; Yamazaki et al., 2017). For example, Haddad et al. (Haddad et al., 2014) demonstrated that a culturally-catered user interface could increase the likelihood of using a computerized cognitive assessment tool compared with a western-centric interface design. More researchers focused on older immigrant’s preferences for digital communication and digital resources, which has guided the recent development of communication channels between older immigrants (Khvorostianov, 2016; Panagakos & Horst, 2006; Zibrik et al., 2015). These finding suggests limited participation rates among older immigrants while relatively younger participants, who have more skills and experience with ICT technology, have higher participation rates (Arcury et al., 2017, 2018; Walters et al., 2017). Low participation rates suggest difficulties in developing technologies that rely solely on older immigrant participation, who then face a doubled exclusion to information in both their age and belonging to an ethnic minority. Instead, the development of new technology could utilize the strengths of caregivers who view the needs of older adults from closer perspectives and interact closely with the older adults and with the relevant technology (Bergschöld et al., 2019; Olsson & Viscovi, 2018).

Research interests of specific minority groups often originate from researchers of the same ethnic background (Chung et al., 2017a, b; Li et al., 2018; Yamazaki et al., 2017). Moreover, older immigrants have shown an increased willingness to participate in in-depth studies with researchers who share the same cultural backgrounds (Chung et al., 2017a, b; Li et al., 2018; Yamazaki et al., 2017). This pattern underlies the difficulties of involving different older immigrant groups in in-depth studies, which leads to generalizing the care needs of excluded minority groups. It also implies that the development and growth of the ethnic community may lead to more research interest of that specific ethnic group in the future, which could broaden the knowledge of that particular ethnic minority group.

Implications of Applied Methodologies

The focus of the studies was heterogeneous since the epistemologies and methodologies varied significantly across research disciplines (Brettell & Hollifield, 2014; Castles et al., 2014). Quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis offered different perspectives and angles on the issue. However, the lack of systematic frameworks in this field hinders researchers in understanding data and cross-comparing results from different disciplines, and creates more difficulties in utilizing, comparing, and exchanging findings and knowledge. It is both necessary and crucial to develop theoretical frameworks that help explain empirical data and connect what may seem like isolated findings in different fields to improve knowledge exchange in this field.

Compared with more generalized social issues, cultural needs and preferences are less studied. This relates to difficulties in conducting studies with immigrants. It also indicates the lack of research attention to emerging migrant populations and older immigrant groups. With the dramatic increase in the migrant population, the welfare system, especially in the new migration destinations with more comprehensive welfare benefits, will face severe challenges in sustainably maintaining its operation, including increasing expenditures, eligibility, and equality. Thus, more research is required to identify future developmental paths for welfare states to resolve their shifting demographics.

Limitations

As the review was strictly based on the PRISMA methods of systematic review, some limitations exist. First, the included studies did not share the same theoretical background in interpreting the experiments which caused difficulties in synthesizing evidence and broadening the application of the results. Second, we could not identify unique ethnic-related characteristics and preferences from the included articles due to the limited number of studies on specific ethnicities. Third, although the initial search criteria did not restrict geographic locations, results were limited to three countries (Australia, the US, and the UK). The search criteria “home care” and “older immigrants” together might exclude societies which either do not have formal home care services or do not show significant demands for professional care at home for older immigrants. Fourth, the included studies did not share a definition of “old”; the researchers each gave an individual definition of “old," limited to that particular study, in which the youngest age varied from 55 to 65. Last but not least, the authors decided to limit the study to articles published in English because of the additional time and expenditure that would be involved in including all publications in other languages.

Conclusion

The findings of this review suggest that older immigrants are more vulnerable than majority groups in terms of socioeconomic status, language proficiency, and risk of social isolation. Although some facilitators could improve the use of technology in these communities, they are not able to address disparities within ethnic communities or between the majority communities and minorities. Older immigrants have shown the potential benefits of using ICT for home care services, if the technology could meet their needs and preferences.

This review presents different aspects of older immigrants across various research disciplines, but it is still not sufficient to depict a complete picture of their experiences. This review suggests that the field would benefit from more scientific interest and greater development of methodologies to support more comprehensive and transferable knowledge.

References

Agree, E. M. (2014). The potential for technology to enhance independence for those aging with a disability. Disability and Health Journal, 7(1 SUPPL), S33–S39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2013.09.004

Anderson, M., & Perrin, A. (2017). Tech adoption climbs among older adults. Pew Research Center.

Angel, J. L., Mudrazija, S., & Benson, R. (2016). Racial and Ethnic Inequalities in Health. In L. K. George & K. F. Ferraro (Eds.), Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences (8th ed., pp. 123–141). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-417235-7.00006-8

Arcury, T. A., Quandt, S. A., Sandberg, J. C., Miller, D. P., Jr., Latulipe, C., Leng, X., Talton, J. W., Melius, K. P., Smith, A., & Bertoni, A. G. (2017). Patient Portal Utilization Among Ethnically Diverse Low Income Older Adults: Observational Study. JMIR Medical Informatics, 5(4), e47. https://doi.org/10.2196/medinform.8026

Arcury, T. A., Sandberg, J. C., Melius, K. P., Quandt, S. A., Leng, X., Latulipe, C., Miller, D. P., Smith, D. A., & Bertoni, A. G. (2018). Older Adult Internet Use and eHealth Literacy. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 39(2), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464818807468

Arora, S., Bergland, A., Straiton, M., Rechel, B., & Debesay, J. (2018). Older migrants’ access to healthcare: A thematic synthesis. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMHSC-05-2018-0032

Barth, E., Moene, K. O., & Willumsen, F. (2014). The Scandinavian model—An interpretation. Journal of Public Economics, 117, 60–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2014.04.001

Bekteshi, V., & Kang, S. (2020). Contextualizing acculturative stress among Latino immigrants in the United States: A systematic review. Ethnicity & Health, 25(6), 897–914. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2018.1469733

Bergschöld, J. M., Neven, L., & Peine, A. (2019). DIY gerontechnology: Circumventing mismatched technologies and bureaucratic procedure by creating care technologies of one’s own. Sociology of Health and Illness, 42(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13012

Berridge, C., Chan, K. T., & Choi, Y. (2019). Sensor-based passive remote monitoring and discordant values: Qualitative study of the experiences of low-income immigrant elders in the United States. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(3). https://doi.org/10.2196/11516

Berry, J. W. (2004). Conceptual approaches to acculturation. In K. M. Chun, P. B. Organista, & G. Marín (Eds.), Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research. (pp. 17–37). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10472-004

Boots, L. M. M., De Vugt, M. E., Van Knippenberg, R. J. M., Kempen, G. I. J. M., & Verhey, F. R. J. (2014). A systematic review of Internet-based supportive interventions for caregivers of patients with dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(4), 331–344. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4016

Brettell, C. B., & Hollifield, J. F. (Eds.). (2014). Migration Theory: Talking Across Disciplines (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Brodaty, H., & Donkin, M. (2009). Clinical research: Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues Clinical Neuroscience, 11(2), 217–228.

Castells, M. (2000). Toward a Sociology of the Network Society. Contemporary Sociology, 29(5), 693–699. https://doi.org/10.2307/2655234

Castells, M. (2002). Local and global: Cities in the network society. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie, 93(5), 548–558. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9663.00225

Castles, S., de Haas, H., & Miller, M. J. (2014). The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World (5th ed.). Palgrave Macmillan Ltd.

Chang, J., McAllister, C., & McCaslin, R. (2015). Correlates of, and Barriers to, Internet Use Among Older Adults. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 58(1), 66–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2014.913754

Chen, X., Östlund, B., & Frennert, S. (2020). Digital Inclusion or Digital Divide for Older Immigrants? A Scoping Review. In Z. J. Gao Q. (Ed.), Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Population. Technology and Society. HCII 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (pp. 176–190). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50232-4_13

Chesser, A., Burke, A., Reyes, J., & Rohrberg, T. (2016). Navigating the digital divide: A systematic review of eHealth literacy in underserved populations in the United States. Informatics for Health & Social Care, 41(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3109/17538157.2014.948171

Chung, J., Demiris, G., Thompson, H. J., Chen, K.-Y., Burr, R., Patel, S., & Fogarty, J. (2017a). Feasibility testing of a home-based sensor system to monitor mobility and daily activities in Korean American older adults. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 12(1), e12127. https://doi.org/10.1111/opn.12127

Chung, J., Thompson, H. J., Joe, J., Hall, A., & Demiris, G. (2017b). Examining Korean and Korean American older adults’ perceived acceptability of home-based monitoring technologies in the context of culture. Informatics for Health and Social Care, 42(1), 61–76. https://doi.org/10.3109/17538157.2016.1160244

Ciobanu, R. O., Fokkema, T., & Nedelcu, M. (2017). Ageing as a migrant: Vulnerabilities, agency and policy implications. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 43(2), 164–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1238903

Cisotto, G., & Pupolin, S. (2018). Evolution of ICT for the improvement of quality of life. IEEE Aerospace and Electronic Systems Magazine, 33(5–6), 6–12. https://doi.org/10.1109/MAES.2018.170114

Demiris, G., Rantz, M. J., Aud, M. A., Marek, K. D., Tyrer, H. W., Skubic, M., & Hussam, A. A. (2004). Older adults’ attitudes towards and perceptions of ‘smart home’ technologies: A pilot study. Medical Informatics and the Internet in Medicine, 29(2), 87–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/14639230410001684387

Derose, K. P., Escarce, J. J., & Lurie, N. (2007). Immigrants and health care: Sources of vulnerability. Health Affairs, 26(5), 1258–1268. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.1258

Ferreira, S. M., Sayago, S., & Blat, J. (2017). Older people’s production and appropriation of digital videos: An ethnographic study. Behaviour and Information Technology, 36(6), 557–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2016.1265150

Franchi, C., Baviera, M., Sequi, M., Cortesi, L., Tettamanti, M., Roncaglioni, M. C., Pasina, L., Dignefa, C. D., Fortino, I., Bortolotti, A., Merlino, L., Mannucci, P. M., & Nobili, A. (2016). Comparison of Health Care Resource Utilization by Immigrants Versus Native Elderly People. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 18(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-014-0152-2

Fret, B., Mondelaers, B., De Donder, L., Switsers, L., Smetcoren, A. S., Verté, D., Smetcoren, A. S., Dury, S., De Donder, L., Dierckx, E., Lambotte, D., Fret, B., Duppen, D., Kardol, M., Verté, D., Hoeyberghs, L., De Witte, N., De Roeck, E., Engelborghs, S., & Schols, J. (2020). Exploring the Cost of ‘Ageing in Place’: Expenditures of Community-Dwelling Older Adults in Belgium. Ageing International, 45(3), 209–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-018-9341-y

Genet, N., Boerma, W. G., Kringos, D. S., Bouman, A., Francke, A. L., Fagerström, C., Melchiorre, M. G., Greco, C., & Devillé, W. (2011). Home care in Europe: A systematic literature review. BMC Health Services Research, 11(1), 207. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-11-207

Goldstein, J. R. (2009). How Populations Age. In International Handbook of Population Aging (pp. 7–18). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-8356-3_1

Goodall, K. T., Newman, L. A., & Ward, P. R. (2014). Improving access to health information for older migrants by using grounded theory and social network analysis to understand their information behaviour and digital technology use. European Journal of Cancer Care, 23(6), 728–738. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12241

Green, G., Bradby, H., Chan, A., & Lee, M. (2006). “We are not completely Westernised”: Dual medical systems and pathways to health care among Chinese migrant women in England. Social Science & Medicine, 62(6), 1498–1509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.014

Haddad, S., McGrenere, J., & Jacova, C. (2014, April). Interface design for older adults with varying cultural attitudes toward uncertainty. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1913-1922). https://doi.org/10.1145/2556288.2557124

Hames, E., Stoler, J., Emrich, C. T., Tewary, S., & Pandya, N. (2016). A GIS Approach to Identifying Socially and Medically Vulnerable Older Adult Populations in South Florida. The Gerontologist, 57(6), gnw106. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw106

Hansen, E. B. (2014). Older immigrants’ use of public home care and residential care. European Journal of Ageing, 11(1), 41–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-013-0289-1

Hao, L. (2004). Wealth of Immigrant and Native-Born Americans. International Migration Review, 38(2), 518–546. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2004.tb00208.x

Hao, L. (2007). Color lines, country lines: Race, immigration, and wealth stratification in America. Russell Sage Foundation.

Hasan, H., & Linger, H. (2016). Enhancing the wellbeing of the elderly: Social use of digital technologies in aged care. Educational Gerontology, 42(11), 749–757. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2016.1205425

Holttum, S. (2016). Do computers increase older people’s inclusion and wellbeing? Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 20(1), 6–11. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-11-2015-0041

Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M. P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M. C., Vedel, I., & Pluye, P. (2018). The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34(4), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180221

Hooyman, N. R., & Kiyak, H. A. (2014). Social Gerontology: A Multidisciplinary Perspective (10th ed.). Pearson Education.

IOM. (2017). World Migration Report 2018. International Organization for Migration. https://www.iom.int/wmr/world-migration-report-2018

Khvorostianov, N. (2016). “Thanks to the Internet, We Remain a Family”: ICT Domestication by Elderly Immigrants and their Families in Israel. Journal of Family Communication, 16(4), 355–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431.2016.1211131

King, C., & Workman, B. (2006). A reality check on virtual communications in aged care: Pragmatics or power? Ageing International, 31(4), 253–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02915424

Li, J., Xu, L., & Chi, I. (2018). Challenges and resilience related to aging in the United States among older Chinese immigrants. Aging & Mental Health, 22(12), 1548–1555. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1377686

Lindberg, B., Nilsson, C., Zotterman, D., Söderberg, S., & Skär, L. (2013). Using Information and Communication Technology in Home Care for Communication between Patients, Family Members, and Healthcare Professionals: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Telemedicine and Applications, 2013, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/461829

Lindeman, D. A., Kim, K. K., Gladstone, C., & Apesoa-Varano, E. C. (2020). Technology and Caregiving: Emerging Interventions and Directions for Research. The Gerontologist, 60(1), S41–S49. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnz178

Liu, X., Cook, G., & Cattan, M. (2017). Support networks for Chinese older immigrants accessing English health and social care services: The concept of Bridge People. Health and Social Care in the Community, 25(2), 667–677. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12357

Lum, T. Y., & Vanderaa, J. P. (2010). Health disparities among immigrant and non-immigrant elders: The association of acculturation and education. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 12(5), 743–753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-008-9225-4

Lutz, W., Sanderson, W., & Scherbov, S. (2008). The coming acceleration of global population ageing. Nature, 451(7179), 716–719. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06516

McAuliffe, M., & Khadria, B. (2019). World Migration Report 2020. In International Organization For Migration. UN. https://doi.org/10.18356/b1710e30-en

Mercer, K., Baskerville, N., Burns, C. M., Chang, F., Giangregorio, L., Goodwin, J. T., Rezai, L. S., & Grindrod, K. (2015). Using a collaborative research approach to develop an interdisciplinary research agenda for the study of mobile health interventions for older adults. JMIR MHealth and UHealth, 3(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.3509

Millard, A., Baldassar, L., & Wilding, R. (2018). The significance of digital citizenship in the well-being of older migrants. Public Health, 158(SI), 144–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2018.03.005

Miner, S., Liebel, D. V., Wilde, M. H., Carroll, J. K., & Omar, S. (2018). Somali Older Adults’ and Their Families’ Perceptions of Adult Home Health Services. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 20(5), 1215–1221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-017-0658-5

Mitchell, U. A., Chebli, P. G., Ruggiero, L., & Muramatsu, N. (2019). The Digital Divide in Health-Related Technology Use: The Significance of Race/Ethnicity. The Gerontologist, 59(1), 6–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny138

Moberg, L., Blomqvist, P., & Winblad, U. (2016). User choice in Swedish eldercare – conditions for informed choice and enhanced service quality. Journal of European Social Policy, 26(3), 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928716645076

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(10), 1006–1012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005

Moon, H. E., Haley, W. E., Rote, S. M., & Sears, J. S. (2020). Caregiver Well-Being and Burden: Variations by Race/Ethnicity and Care Recipient Nativity Status. Innovation in Aging, 4(6), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igaa045

Olsson, T., & Viscovi, D. (2018). Warm experts for elderly users: Who are they and what do they do? Human Technology, 14(3), 324–342. https://doi.org/10.17011/ht/urn.201811224836

Östlund, B. (2005). Design Paradigmes and Misunderstood Technology: The Case of Older Users. In B. Jæger (Ed.), Young technologies in old hands - An international view on senior citizen’s utilization of ICT (pp. 25–39). DJØF Publishing Copenhagen.

Pace, R., Pluye, P., Bartlett, G., Macaulay, A. C., Salsberg, J., Jagosh, J., & Seller, R. (2012). Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 49(1), 47–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.07.002

Panagakos, A. N., & Horst, H. A. (2006). Return to Cyberia: Technology and the social worlds of transnational migrants. Global Networks, 6(2), 109–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0374.2006.00136.x

Pluye, P., Gagnon, M. P., Griffiths, F., & Johnson-Lafleur, J. (2009). A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in Mixed Studies Reviews. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(4), 529–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.01.009

Reneland-Forsman, L. (2018). ‘Borrowed access’–the struggle of older persons for digital participation. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 37(3), 333–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2018.1473516

Ruspini, P. (2009). Elderly Migrants in Europe: an Overview of Trends, Policies and Practices.

Selwyn, N., Gorard, S., Furlong, J., & Madden, L. (2003). Older adults’ use of information and communications technology in everyday life. Ageing and Society, 23(5), 561–582. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X03001302

Sixsmith, J., Sixsmith, A., Fänge, A. M., Naumann, D., Kucsera, C., Tomsone, S., Haak, M., Dahlin-Ivanoff, S., & Woolrych, R. (2014). Healthy ageing and home: The perspectives of very old people in five european countries. Social Science and Medicine, 106, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.006

Tatara, N., Kjøllesdal, M. K. R., Mirkovic, J., & Andreassen, H. K. (2016). eHealth Use Among First-Generation Immigrants From Pakistan in the Oslo Area, Norway, With Focus on Diabetes: Survey Protocol. JMIR Research Protocols, 5(2), e79. https://doi.org/10.2196/resprot.5468

Treas, J., & Gubernskaya, Z. (2016). Immigration, Aging, and the Life Course. In L. K. George & K. F. Ferraro (Eds.), Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences (pp. 143–161). Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-417235-7.00007-x

UN DESA. (2019). International Migration 2019: Report. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315634227

United Nations. (2017). World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision, Key Findings and Advance Tables. (ESA/P/WP/248.).

Vasunilashorn, S., Steinman, B. A., Liebig, P. S., & Pynoos, J. (2012). Aging in Place: Evolution of a Research Topic Whose Time Has Come. Journal of Aging Research, 2012, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/120952

Walsh, K., & Callan, A. (2011). Perceptions, Preferences, and Acceptance of information and communication technologies in older-adult community care settings in Ireland: A case-study and ranked-care program analysis. Ageing International, 36(1), 102–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-010-9075-y

Walters, K., Kharicha, K., Goodman, C., Handley, M., Manthorpe, J., Cattan, M., Morris, S., Clarke, C. S., Round, J., & Iliffe, S. (2017). Promoting independence, health and well-being for older people: A feasibility study of computer-aided health and social risk appraisal system in primary care. BMC Family Practice, 18(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-017-0620-6

Warnes, A. M., Friedrich, K., Kellaher, L., & Torres, S. (2004). The diversity and welfare of older migrants in Europe. Ageing and Society, 24(3), 307–326. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X04002296

Wejnert, B. (2002). Integrating Models of Diffusion of Innovations: A Conceptual Framework. Annual Review of Sociology, 28(1), 297–326. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.28.110601.141051

Wiklund-Axelsson, S., Melander-Wikman, A., Näslund, A., & Nyberg, L. (2013). Older people’s health-related ICT-use in Sweden. Gerontechnology, 12(1), 36–43. https://doi.org/10.4017/gt.2013.12.1.010.00

Wolfson, T., Crowell, J., Reyes, C., & Bach, A. (2017). Emancipatory Broadband Adoption: Toward a Critical Theory of Digital Inequality in the Urban United States. Communication, Culture and Critique, 10(3), 441–459. https://doi.org/10.1111/cccr.12166

Yamazaki, Y., Yontz, V., & Hayashida, C. (2017). Propensity for Japanese-American older adults’ use of medical alert services in Hawaii. Geriatrics and Gerontology International, 17(10), 1392–1398. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12871

Zeissig, S. R., Singer, S., Koch, L., Zeeb, H., Merbach, M., Bertram, H., Eberle, A., Schmid-Höpfner, S., Holleczek, B., Waldmann, A., & Arndt, V. (2015). Utilisation of psychosocial and informational services in immigrant and non-immigrant German cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology, 24(8), 919–925. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3742

Zhao, X., Yang, B., & Wong, C. W. (2018). Analyzing Trend for U.S. Immigrants’ e-Health Engagement from 2008 to 2013. Health Communication, 34(11), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2018.1475999

Zibrik, L., Khan, S., Bangar, N., Stacy, E., Novak Lauscher, H., Ho, K., Lauscher, H. N., & Ho, K. (2015). Patient and community centered eHealth: Exploring eHealth barriers and facilitators for chronic disease self-management within British Columbia’s immigrant Chinese and Punjabi seniors. Health Policy and Technology, 4(4), 348–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlpt.2015.08.002

Funding

Open access funding provided by Royal Institute of Technology. Open access funding is provided by KTH Royal Institute of Technology

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The first author (XC) had the idea for the article and discussed with the second and the third author on the detail of the literature search method. The first author (XC) performed the literature search and conducted data analysis and drafted the manuscript. The second (BÖ) and third (SF) authors critically revised the work and gave suggestions. All authors have reviewed the paper and approve the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Informed Consent and Ethical Treatment of Experimental Subjects (Animal and Human)

The article used only the materials and conducted the literature review.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, X., Frennert, S. & Östlund, B. The Use of Information and Communication Technology Among Older Immigrants in Need of Home Care: a Systematic Literature Review. Ageing Int 47, 238–264 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-021-09417-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-021-09417-x