Abstract

There was a strong push from employers to decentralize wage setting in Finland in the early 2000s. We analyze the incidence of decentralization and its effect on the level and dispersion of wages by using nationally representative panel data. The results show that wage setting was more likely decentralized in collective agreements where a high share of employees worked in manufacturing or real estate industries than in other industries, such as in education and human health and social work activities. Decentralization was, for the most part, quite short-lived. Using recent difference-in-differences methods that allow for heterogeneous treatment effects and differences in the timing of treatment, we show that decentralization had modest positive effects on the level and dispersion of wages in manufacturing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There has been a strong tendency toward decentralization of collective bargaining in many European countries (Visser 2016, p. 313). This means that wage negotiations have moved closer to the individual enterprise. Centralized collective bargaining systems have traditionally been seen to reduce wage inequality (e.g., OECD 2004; Blau and Kahn 1999; Rowthorn 1992), which has attracted the attention of scholars to the effects of decentralization on both wages and wage dispersion.

Although decentralization of wage bargaining has been associated with higher earnings in many empirical studies,Footnote 1 evidence regarding wage dispersion is more mixed. Some studies find that decentralization is related to increased wage dispersion (Card and de la Rica 2006; Dahl et al. 2013; Addison et al. 2017), some find mixed evidence (Dell’Aringa and Pagani 2007, Plasman et al. 2007; Cirillo et al. 2019), while others find a negative relationship (Canal Domínguez and Gutiérrez 2004).

There are several reasons for these differences in the results. First, the literature on decentralized bargaining has no consensus on how decentralization or wage dispersion should be measured. Second, the extent or effects of decentralization may vary even within countries. For example, decentralization may be more common in manufacturing in some countries and in services in other countries. In addition, the effects of decentralization may depend on the preferences and bargaining power of the parties involved (Dell’Aringa and Pagani 2007, p. 31). For example, decentralization may increase wage dispersion more in settings where the bargaining parties accept larger wage differences. Third, the literature is mostly based on cross-sectional estimates, which suffer from severe endogeneity issues. The few studies that can account for firm and employee selection into different collective agreements find reduced estimates of the links between decentralization and wages (Dahl et al. 2013; Gürtzgen 2016). However, recent literature has shown that even these studies may not be able to correctly identify treatment effects because these effects are likely to be heterogeneous and because the timing of the treatment differs (see, e.g., de Chaisemartin and d'Haultfoeuille 2020).

Although the impacts of decentralization have been studied quite actively, the incidence of decentralization, or in what kind of industries or employee groups decentralization has taken place, has received less attention. We know of only two studies that examine the incidence of decentralized wage setting by using statistical models (Granqvist and Regnér 2008; Addison et al. 2017). Thus, there is little information on how decentralization takes place within countries, whereas there has been more emphasis on classifying the collective bargaining systems of countries (see, e.g., Garnero 2021).

We use Finnish data to study the incidence and impacts of the decentralization of collective bargaining. During the period we study, there was a move from a very centralized collective bargaining system toward a more decentralized system. Employers felt that the existing collective bargaining system was too inflexible and did not provide sufficient incentives for employees (Alho et al. 2003). They felt that a more decentralized wage setting would improve these shortcomings. Although employers wanted more local bargaining, labor unions, especially blue-collar unions, resisted local bargaining (Heikkilä and Piekkola 2005). However, limited decentralization took place within the collective bargaining system, meaning that the Finnish case is an example of organized decentralization (Traxler 1995).

Traditionally, the key outcome of centralized collective bargaining has been the general wage increase, which stipulates the extent to which the wages of everyone should be increased in a given sector. The key characteristic of decentralization is that in addition to the general increase, there is a local wage increase allowance, which can be allocated locally. An example would be a contract that stipulates a 2% general increase and a 1% local wage increase allowance. Everyone would receive a 2% wage increase and the remaining 1% would be allocated to employees according to firm-level negotiations. Some employees might exprience only a general increase of 2% while others could obtain an additional 4% increase from the local wage increase allowance. In the following, we use the term “local pot” for the local wage increase allowance.

The key to our analysis is administrative register data matched with collective bargaining data spanning the years 2006–2013. The individual data are aggregated at the collective agreement-year level. Our empirical approach follows state-of-the-art methods in the literature on decentralization (de Chaisemartin and d'Haultfoeuille 2020). These methods allow us to identify the treatment effect of decentralization even when the treatment effects are heterogeneous, and the timing of the treatment differs. Such methods have not been previously used in the literature studying the effects of decentralization on wages.

Our contribution to the literature is twofold. First, we study what kind of collective agreements include decentralized elements. Thus, we contribute to the scarce literature on the incidence of decentralized bargaining. Second, we provide credible estimates of the impacts of decentralization. The methods we use overcome some of the shortcomings in the methods used in the existing literature.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Sect. “Related Literature” discusses the relevant literature, and Sect. “Institutions and Background” presents the institutional background for the Finnish labor market. Sect. “Data and Methods” describes the Finnish register datasets and explains our empirical approach based on Harmonized Structure of Earnings Survey (HSES) data matched with private sector collective bargaining data for the period 2005–2013. Sect. “Results” provides the various estimation results, while the final section concludes the paper by placing our findings in a larger context.

Related Literature

The standard view suggests that centralized collective bargaining systems reduce wage dispersion. This argument has been confirmed in earlier studies (e.g., Blau and Kahn 1999; Rowthorn 1992), as well as in OECD cross-country analyses (e.g.,OECD 2004). As several advanced countries have experienced a process toward more decentralized wage bargaining, examination of the implications of such decentralization for pay determination has attracted increased attention. Below we review this literature, but before that, we review the few studies that have considered the incidence of decentralized bargaining.

These studies show that there is considerable heterogeneity in collective bargaining systems within a single country. For example, evidence from Nordic countries shows that firm-level bargaining is more common among skilled workers than among unskilled workers (Dahl et al. 2013, Table 3). Among workers, who are academics or graduate professionals with a higher degree, the probability of decentralized wage bargaining is higher in the private sector than in the public sector, and among graduate engineers and in law and business administration and economics occupations (Granqvist and Regnér (2008). Finally, the probability of leaving collective agreements is higher in smaller plants, in non-organizational plants, and in plants with a strong concentration of highly skilled employees in Germany (Addison et al. 2017).

Decentralized Bargaining and Wages

Typically more decentralized wage bargaining leads to higher wages.Footnote 2 The findings from Spain indicate that employees under a firm-level or single-employer contract earn a wage premium of between 3 and 10% (Canal Domínguez and Gutiérrez 2004, Card and de la Rica 2006, Plasman et al. 2007, Ramos et al. 2022). Similar wage premium of approximately 3%-6% associated with firm-level bargaining is also observed in Denmark (Plasman et al. 2007; Dahl et al. 2013), whereas employees working under a more decentralized wage-setting system earn approximately 5% more in Belgium (Plasman et al. 2007; Rycx 2003). Higher coverage at the firm or industry level is also associated with higher wages in Germany (Fitzenberger et al. 2013). Granqvist and Regnér (2008) offer a different type of measure for decentralized wage bargaining in Sweden. They find that workers who have either participated in pay reviews or negotiated their own wages with a manager earn 1%-5% higher earnings.

Decentralized Bargaining and Pay Dispersion

Collective bargaining may also be related to the dispersion of wages, but these results are more mixed than those regarding the level of wages. The results for Italy provide (inconclusive) evidence of the negative association between single-employer bargaining and wage dispersion (Dell’Aringa and Pagani 2007). In contrast, firm-level bargaining has been shown to be associated with higher pay dispersion in Denmark (Plasman et al. 2007; Dahl et al. 2013) and in Ireland (McGuinnes et al. 2010). The findings for Germany suggest either no clear-cut effect, or only a modest increase in wage dispersion (Fitzenberger et al. 2013, Addison et al. 2017).

The findings regarding the effect of decentralized wage bargaining on pay dispersion thus vary between countries, but sometimes the results also vary within a single country, such as in Spain. This inconclusive evidence is likely explained by the use of different measures and econometric methods. Card and de la Rica (2006) and Ramos et al. (2022) use quantile regression to evaluate the effect of firm-level contracting along the earnings distribution, and they find that decentralization is related to increased wage dispersion. Canal Domínguez and Gutiérrez (2004) and Plasman et al. (2007), on the other hand, use the standard deviation of hourly wages as a measure of wage dispersion and the Blinder–Oaxaca decomposition method. They find that decentralization is related to decreased wage dispersion.

Studies regarding wage bargaining in Belgium also provide inconclusive associations with wage dispersion. Plasman et al. (2007) show that single-employer agreements are associated with slightly higher wage dispersion, whereas Dell’Aringa and Pagani (2007) show the opposite. The difference between these results may be driven by the fact that the analysis of Plasman et al. (2007) was restricted to employees in the manufacturing sector for both male and female employees. Rycx (2003) shows that dispersion in the inter-industry wage differential is estimated to be either higher or lower under company-level agreements, depending on the estimation method used.

Institutions and Background

This section provides the necessary institutional background needed for understanding the nature of decentralization in Finland and the modeling choices. It explains the role of local pots in Finnish collective agreements and how the contracts of blue-collar and white-collar employees differ. It also provides evidence on the preferences of blue-collar and white-collar employees for local bargaining and wage dispersion.

Collective Bargaining in Finland

Finland is characterized by highly controlled collective agreements (e.g., Jonker-Hoffrén 2019). Collective agreements play a large role in the labor market due to the high coverage of collective bargaining (approximately 90%), the widespread extension of collective agreements, and the wide scope of the agreements. The union density rate is also quite high in Finland, even though it has been declining. The union density rate among wage earners was nearly 75% in 2000 and almost 60% in 2022.

Bargaining takes place at the sectoral level, and the actors are employers’ federations and trade unions. In most sectors, blue-collar, white-collar, and sometimes upper-white-collar employees have separate contracts. Blue-collar employees are paid hourly, and their remuneration is based on time pay, piece rates, and reward rates. Wage supplements such as shift allowances may also be important for blue-collar employees. White-collar employees are paid monthly. Both groups may also receive performance-related pay, which is not governed by collective agreements. Performance-related pay is typically only a small portion of earnings. If employees are paid bonuses, they are on average approximately 5% of regular earnings for blue-collar employees and 8% for white-collar employees (Kauhanen and Napari 2012). The different contracts and different modes of pay suggests conducting separate estimations for blue- and white-collar employees.

The contract applied to each employee is determined by their employer’s federation or industry if it does not belong to an employer’s federation. Employers have a very limited possibility of choosing their contract.

Collective agreements cover, for example, wage formation, working time, holidays, social provisions, and parental leave (e.g., Jonker-Hoffrén 2019). The general increase is typically the most important element in a collective agreement. It stipulates how much each employee’s individual wage is increased. Often, this is the only wage increase component, which means that everyone’s wages are increased in the same way.

For our purposes, the most interesting element is the local pot. These are wage increases that are negotiated and implemented locally according to the rules set in the collective agreement. The local negotiations are carried out by a representative of the employees (typically the shop steward) and a representative of the employee. Local pots used to be rare, but their prevalence increased notably at the beginning of the twenty-first century, especially in the years 2007–2008. Local pots are the primary way in which the Finnish collective bargaining system has become decentralized.

Local pots often include a fallback clause, which means that if local negotiations are not successful, the wage increase will be implemented as a general wage increase. Sometimes the fallback wage increase is of the same size as the locally negotiated increase and sometimes it is smaller. When the fallback (general) wage increase is smaller than the locally negotiated wage increase, there are incentives for the employee side to conduct local negotiations. Employers, on the other hand, are willing to accept higher contractual increases if they can affect how the increases are allocated because this should reduce wage drift. In essence, employers can use wage increases from collective agreements to implement their wage policy.

As an example of collective agreements, consider the agreement for blue-collar employees in technology industries in 2007. It stipulated a 3.4% general increase and a 1% local pot with a 0.7% fallback clause. This means that the wages of each worker were increased by 3.4% and, if the parties at the firm level could agree on the implementation of the local pot, the wages would increase on average by 1% more. However, if the local negotiations were unsuccessful, the total wage increase for each worker would be 4.1% (3.4% + 0.7%). Thus, the only issue that is negotiated at the firm level is how the local pot is distributed among workers; all other issues are determined at the sectoral level.

Private sector employers can always pay more and increase wages more than is stipulated in the contracts. In practice, wages do often increase more than contracts stipulate. This is called wage drift.Footnote 3 More information on the development of the bargaining structure in Finland can be found in the Online Appendix.

Views on Local Bargaining and Wage Dispersion

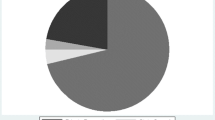

Figure 1 shows the differences in the preferences of white-collar and blue-collar employees with respect to decentralization and wage dispersion. Notes: Five options were given for the level of wage negotiations: individual level, firm level, industry level, centralized income policy agreement (TUPO), and European level. Four options were given for how the firm-level wage increases should be implemented: to increase incentives, the same absolute increase for all workers, the same percentage increase for all workers, and increases targeted towards the lowest earnings bracket. A total of 441 blue-collar workers and 804 white-collar workers responded to the survey. Source: Alho et al. 2003. These findings are important for the interpretation of our empirical results concerning the incidence of local pots. This figure draws on a survey carried out in 2002 and shows that blue- and white-collar workers differed markedly in their preferences (Alho et al. 2003).Footnote 4 The figure shows that white-collar workers preferred wage increase negotiations to be held at the firm level more than blue-collar workers did. Over 40% of the white-collar workers chose the firm level as the best or second-best option for the level of wage negotiations, while this was the case for less than 20% of the blue-collar workers.

Moreover, views on how firm-level wage increases/local pots should be implemented differ. A large portion of the blue-collar workers (45%) preferred local pots to be targeted toward the lowest earnings brackets or to have the same absolute increases for all workers (32%), while white-collar workers preferred them to be implemented to increase wage incentives (40%) or to have similar percentage increases for all workers (24%). These results mean that blue-collar employees believe that locally bargained wage increases should be used to decrease wage dispersion, whereas white-collar employees believe that they could be allocated in a way that increases wage dispersion. Given these drastic differences in preferences, it is likely that the incidence and perhaps the effects of decentralization will differ by worker group.

Expected Effects of Local Pots

The impact of local pots on wage increases is ambiguous. On the one hand, if the unions want to be compensated for the inclusion of the pots in the contract, the contractual increase may be higher than it would be if the general increase was the only wage increase element. On the other hand, if unions do not make such demands, the size of the contractual increase may not depend on the structure of the wage increases. The existence of a local pot may also impact the eventual wage drift and thus the actual wage increases. If employers can differentiate wage increases among employees, they may have less need to increase individual wages above the increases stipulated in contracts. In other words, they can conduct the desired wage policy within the collective bargaining system, and they do not need to use additional resources to conduct their wage policy.

The existence of a local pot in the contract will (weakly) increase wage dispersion, but the extent to which this occurs depends on many issues. Wage dispersion cannot decrease from the introduction of a local pot because the wage increases will be weakly more unequal in such contracts. However, it is possible that local pots are used to increase everyone’s wages similarly (in percentage terms), which means that the impact on wage dispersion will not differ from the general increase. Based on the previous section, this is likely more common for the blue-collar employees than for white-collar employees. It may also be the case that the local pots are so small in relation to the general increase and the typical variation in the measured wage increases, that empirically detecting the impact might be challenging.

Data and Methods

Harmonized Structure of Earnings Survey

The analysis in this study is based on rich, linked data that combine two data sources. The key data for our analysis are the HSES data from Statistics Finland, which includes individual and firm identifiers.Footnote 5 In the data, all wage measures and variable classifications, such as occupation and industry, are consistent across years and sectors, which makes the data suitable for panel analysis. Harmonization of the data is particularly important for our analysis because it takes into account the differences and changes in collective agreements, wage concepts, and compensation components.

The earnings structure statistics are based on firm- and individual-level payroll records data from member firms in employer federations. An augmenting survey for non-member firms and sectors that are not covered by EK is also conducted by Statistics Finland. The HSES data are available for private sector firms annually from 1995 onward. In our analysis, we use the period 2006–2013, which includes both post- and pre-financial crisis years. The data cover 55%-75% of employees, depending on the year and industry. The coverage is less than 100% and differs by industry since the following groups are not included in the survey: firms with fewer than five employees; agriculture, forestry, and fisheries industries; household employers and international organization employees; top management, owners, and their family members; and employees whose job contracts began or ended during the months of data collection. Furthermore, there is limited coverage of employees in unorganized, mostly small, firms.

The HSES data include detailed information on earnings from either the fourth quarter or October, depending on the industry and employee group. The data include two alternative earnings measures. Regular hourly earnings include all pay components that are paid regularly divided by standard contractual hours. This measure excludes overtime pay but includes pay supplements that are paid regularly. Total hourly earnings is the widest earnings measure available. It also includes overtime pay and annual bonuses. The earnings are divided by total hours worked (regular hours + overtime).

We focus on total hourly earnings because we want to capture all the ways in which decentralization can be linked to wage increases. Decentralization may affect, for example, the variable pay elements that the employer can decide on unilaterally. Incentive pay systems are not regulated by collective agreements, except for piece-rate and reward-rate systems for blue-collar employees (Kauhanen and Napari 2012, p. 654). Accordingly, decentralization may affect total earnings via wage drift rather than via bargained wages (Cardoso and Portugal 2005).

Collective Agreement Data

To these data, we match data collected by Kotilainen (2018) from private sector collective agreements and supporting documents.Footnote 6 The collective agreement data contain information on the magnitudes and timing of wage increases stipulated by the contracts. The data include a total of 776 manually collected contracts, approximately 80% of which are generally binding. For our purposes, the most important information concerns whether there was a local pot in the collective agreement in a given year.

HSES data do not contain information on collective agreements at the individual level. It is, however, possible to match the collective bargaining data with the HSES data. Kotilainen (2018) created a mapping of the collective agreements data to the structure of earnings data based on detailed information on industry and occupation.Footnote 7 Approximately 17% of employees in the HSES data could be mapped into more than one collective agreement. In these cases, the individuals were mapped into the generally binding agreement. If all the agreements are generally binding or non-binding, then the contract with the largest number of employees was chosen.Footnote 8

In the empirical analysis, “Local pot” is an indicator variable that equals one if the collective agreement has a local pot in a given year. The comparison category in the analyses is thus collective agreements without local pots. Most often the contracts in the comparison category involve only a general increase.Footnote 9

Together, the HSES data and the collective agreement data provide all that is necessary for reliable analyses of local pots and wages. The data contain enough collective agreements and variation in local pots over time. Importantly, we can link individuals’ earnings to collective agreements. This would not be possible with annual wage information since individuals may change collective agreements during the year. Moreover, both the HSES and the collective agreement data are of high quality.

Econometric Method

We aggregate the data to the collective agreement-year level. We do this for two reasons. The first reason is that we can analyze the impacts of decentralization on the level of wages and wage dispersion using the same method, which allows for heterogeneous treatment effects and differences in the timing of treatment. If we were to analyze the data at the individual level, we would need to use unconditional quantile regressions to study wage dispersion, and that setting would not allow for difference-in-differences analysis that allows for heterogeneous treatment effects and differences in the timing of the treatment. The second is that aggregating the data and weighting by the number of individuals may lead to more reliable standard errors when the number of clusters is not very large (Angrist and Pischke 2009, p. 313).

Previous empirical evidence on how decentralization affects the level and dispersion of wages often relies on a two-way fixed-effects (TWFE) empirical model (see, for example, Gürtzgen 2016; Dahl et al. 2013). This approach is problematic if treatment effects are heterogeneous. Specifically, de Chaisemartin and d'Haultfoeuille (2020) show that if treatment effects are heterogeneous, the TWFE model does not identify them. Moreover, the associated biases can be severe. For example, de Chaisemartin and d'Haultfoeuille (2020) show that the estimate in the TWFE model may be negative even if all the treatment effects are positive. The authors develop an estimator that identifies the average treatment effect even when the treatment effects are heterogeneous, as they almost certainly are in the present case since the treatments are heterogeneous (the magnitude of the local pot varies from one contract to another) and the preferences of the parties differ among collective agreements (blue-collar workers prefer more egalitarian wage structures than white-collar employees). If the treatment effects are homogeneous, the estimator coincides with the TWFE estimator.

The DIDM estimator proposed by de Chaisemartin and d'Haultfoeuille (2020) compares the evolution of outcomes between treatment and comparison groups. The treatment groups are defined in the familiar way, that is, groups that undergo a change (the treatment) between periods t − 1 and t. The comparison groups are defined as those that do not undergo a change between periods t − 1 and t but whose value in period t − 1 corresponds to the treatment group’s value in period t − 1. As an example, collective agreements that move from not having local pots in year t − 1 to having them in year t are compared to collective agreements that do not have local pots in either year.

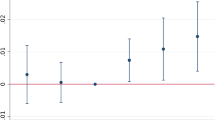

For identification, the method relies on parallel trends for the potential outcomes. This identifying assumption can be assessed using the empirical methods developed in de Chaisemartin and d'Haultfoeuille (2020). The idea is based on conducting placebo tests using the time period(s) preceding the treatment. We consider placebo estimates for period t − 1, given that the treatment occurs in period t (i.e., an industry adopts local pots in period t). That is, the model is estimated as if the adoption of local pots took place in period t − 1 instead of t. The estimates of interest are more credible if the corresponding estimates from the placebo tests are all close to zero in a statistical sense.

The standard errors are clustered at the level of collective agreements. All the results are weighted by the number of employees in the collective agreement. This weighting reflects the importance of each collective agreement in the whole labor market. We estimate the models using the Stata command developed in De Chaisemartin et al. (2019).

The DIDM estimator is appropriate for our data. The estimator also provides consistent estimates when i) the treatment effects are heterogeneous across units or over time, ii) treatment takes place at different points in time, iii) and units may revert to the non-treated state from being treated. All of these factors characterize the setting of our study. Moreover, the key identifying assumptions can be empirically evaluated.

We study the effect of decentralized bargaining on wages and wage dispersion. In addition to the hourly wage level, we also concentrate on hourly wage increases (as, e.g., Dahl et al. 2013; Gürtzgen 2016). We use two measures to define wage dispersion, namely the standard deviation of hourly wages and the 90/10 ratio of hourly wages. As an additional outcome variable, we study the effect of decentralization on the wage drift. To study whether the effects differ by preferences, we examine the implications of decentralization separately for white-collar and blue-collar workers, and for two broadly defined sectors (manufacturing and services). The definitions and classifications of the independent variables are presented in the Online Appendix Table A2.

We split the subsamples based on collective agreement-level averages. For example, the subsample of blue-collar workers refers to collective agreements where more than 50% of the employees are blue-collar workers. We prefer this to the alternative of doing the aggregation starting from the individual level, that is, choosing first all blue-collar workers and then aggregating the data to the collective agreement level. The reason is that we want to capture the collective agreements that pertain to blue-collar workers since the contents of the agreements are likely to differ from the contracts that pertain mainly to white-collar workers. For example, in the case of blue-collar workers, aggregation from the individual level would mean that the subsample contains 90 collective agreements, whereas there are only 72 collective agreements that cover mostly blue-collar workers. Thus, we would include many contracts in the analysis that mainly pertain to white-collar workers if we were to perform the aggregation from the individual level.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Figure 2 shows the prevalence of local pots for white-collar workers and blue-collar workers.Footnote 10 It is seen from the figure that there is variation over time in the share of employees in contracts with local pots. There was a spike in 2008, after which the incidence declined. On average, the prevalence of local pots is quite similar among blue-collar and white-collar workers.

Table 1 shows the variation in the local pot variables at the level of collective agreements. This variation is used in the empirical analysis to identify the relationships between local pots and wage determination. The table shows that there are transitions both into and out of local pots. For example, approximately 11% of collective agreements that did not include a local pot in year t has them in year t + 1. Additionally, approximately 45% of the collective agreements that included a local pot in year t did not have them anymore in year t + 1.

Figure 3 shows the average wage change, contractual increase, and local pot in percentage terms for 2006–2013. The average wage change is the annual weighted average of all collective agreements. The contractual increase in percentage terms is calculated only for contracts that had increases in percentages. This excludes contracts that had increases in euros or cents (about 20% of covered employees). The contractual increase includes the local pot if it was included in the contract. The average local pot is calculated for the contracts that had it. It is seen from the figure that contractual increases and local pots were at their highest levels in 2008. Local pots are in all years clearly below 50% of the contractual increase.

The Incidence of Local Pots

We start the empirical analysis by considering the incidence of local pots. In the regressions, the dependent variable is the local pot indicator. The explanatory variables are industry (14 categories), occupation (7 categories), level of education (6 categories), age (5 categories), firm size (5 categories), and year indicators. All explanatory variables are averages at the collective agreement level. For example, the industry variables show the fraction of employees within a given collective agreement in each of the 14 industries. Of course, very often all employees in a given contract are employed in a single industry. The model is estimated by OLS.

The results in Table 2 show that local pots were more likely to be implemented in collective agreements where a high share of employees work in manufacturing or real estate industries than in other industries, such as in education and human health and social work activities. The results from the full model in column (2) indicate a lower impact of individual-level characteristics. For example, there is some evidence indicating that local pots were more common in collective agreements where a large share of employees were associate professionals than professionals and in collective agreements where a high share of employees were older (more than 55 years old) than younger (18–25 years old).

In Table A4 in the Online Appendix, explore whether the results are driven by few large collective agreements by omitting the weights from the incidence regression. The results are similar to those obtained using weights; local pots are more likely to be implemented in collective agreements where a high share of employees work in manufacturing or real estate, while individual-level characteristics have a lower impact.

The Effects of Local Pots on Wage Increases and Wage Dispersion

Now, we turn to the study of how decentralization affects wages and wage dispersion. Table 3 reports the estimation results for all collective agreements. The table shows the average treatment effect with respect to the local wage pot indicator. The results in column (1) show that decentralization is marginally related to higher hourly wages by approximately 0.14 euros. However, the results are statistically insignificant for wage increases, wage dispersion and wage drift (refer to columns (2)-(5)).

We have tested the robustness of the main results using different methods. First, we use the TWFE model. However, as discussed in Sect. “Econometric Method”, using a TWFE model is problematic if treatment effects are heterogeneous. Hence, the estimates might not be identified properly. The results are shown in Table A5 in the Online Appendix. The results for the wage level are in line with our main results, indicating that a local pot is associated with a higher wage level of approximately 0.20 euros. We also find that the wage drift may decrease by less than 1% when using the TWFE.

We have also tested whether our results are robust to using individual-level data. We present the results using the DIDM estimator and individual-level data in the Online Appendix Table A6. The point estimates concerning wage increases and wage drift using individual-level data are similar to our main results using aggregated data, but the magnitude of the coefficient concerning wage level is smaller (0.05 euros) and imprecisely estimated.

Heterogeneity in the Effects by Occupation Group and Industry

We estimate the models separately for blue-collar and white-collar employees because their contracts and their views on local bargaining differ. The results for blue-collar employees (Table 4) refer to collective agreements in which more than 50% of the covered employees are blue-collar workers. Accordingly, the results for white-collar employees (Table 5) refer to collective agreements in which more than 50% of the covered employees are white-collar workers. We find a modest effect of decentralization on the wage level for both blue-collar workers (0.3 euros) and white-collar workers (0.17 euros). For blue-collar workers, we also find that the wage increases are 3% higher when collective agreements have a local pot. For the sample including all collective agreements, decentralization does not affect wage dispersion nor wage drift.

Finally, we estimate the models for two broadly defined industries, namely manufacturing and services. Tables 6–7 show the average treatment effects of the local wage pot variables. The results show that a decentralized wage setting increases the wage level by approximately 0.2 euros per hour in collective agreements where more than 50% of the covered employees work in the service sector (Table 6). The effect is statistically significant at least at the 5% significance level. None of the other outcome variables are affected by decentralization. However, we find stronger effects of decentralization for collective agreements where more than 50% of the covered employees work in the manufacturing sector (Table 7). The results indicate that the wage level is almost 0.4 euros, and the wage increase is almost 3% higher when collective agreements had local pots than when they did not. Decentralization also positively affects the 90/10 ratio of hourly wages.

To assess the validity of the identifying assumptions, we estimated placebo effects for the period t − 1, using the method of de Chaisemartin and d'Haultfoeuille (2020). These results are shown in the lower parts of Table 3–7. All placebo estimates are statistically insignificant, which supports the validity of the identifying assumptions.

Conclusion

We use Finnish administrative register data matched with collective bargaining data spanning the years 2006–2013 to study the incidence and impacts of decentralization. To credibly estimate the effects of decentralization on wage increases and wage dispersion, we use recent difference-in-differences methods that allow for heterogeneous treatment effects and differences in the timing of treatment (i.e., de Chaisemartin and d'Haultfoeuille (2020).

During the period we study, there was a move from a very centralized collective bargaining system toward a more decentralized system in Finland. Traditionally, the key outcome in centralized collective bargaining was the general wage increase, which stipulated the extent to which wages would be increased in a given sector. The key form of decentralization was that in addition to the general increase, there was a local wage increase allowance (local pot), which could be allocated locally.

We show that decentralization was more likely to occur in collective agreements in the manufacturing sector. Contracts with a large share of plant and machine operators were less likely to include local pots. These results are consistent with prior research showing that blue-collar employees prefer centralized bargaining and egalitarian wage structures more than white-collar employees (Pekkarinen and Alho 2005; Alho et al. 2003). The results also show that decentralized wage setting was most common in the year 2008. This reflected the push of employers to decentralize wage setting in Finland. However, the increase in the prevalence of local pots was quite short-lived.

We also show that decentralization only has a modest effect on the level of wages or wage dispersion. The strongest effects were found for blue-collar workers and for workers in the manufacturing sector, where the wage increases were approximately 3% higher for collective agreements with a local pot than for those without a local pot. The 90/10 ratio of hourly wages also increased in response to decentralization in the manufacturing sector. Thus, in Finland, the decentralization of wage setting was short-lived, and the impacts were quite muted.

The results show that the incidence of decentralization may vary a lot within a given collective bargaining system and that the effects are also heterogeneous. This means that classifications of collective bargaining systems often miss important heterogeneity within countries. Additionally, as emphasized by Gürtzgen (2016), it is difficult to estimate “the” impact of decentralization on wages, as the impacts are heterogeneous. These facts point to the need to analyze decentralization and its effects on a case-by-case basis.

Data Availability

The Structure of Earnings Survey used in this paper is available from Statistics Finland, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study and so are not publicly available. The specific instructions to obtain access to the data are available at http://tilastokeskus.fi/tup/mikroaineistot/hakumenettely_en.html. The collective bargaining dataset has been collected by an independent researcher. Please contact the corresponding author for information about access to these data.

Notes

See, e.g., Canal Domínguez and Gutiérrez (2004), Card and de la Rica (2006) and Plasman, Rusinek and Rycx (2007) for evidence for Spain; Fitzenberger et al. (2013) and Gürtzgen (2016) for Germany; Dahl et al. (2013) and Plasman et al. (2007) for Denmark; Rycx (2003) and Plasman et al. (2007) for Belgium evidence.

Table A1 in the Online Appendix provides a concise overview of the findings in the literature.

More details on the survey can be found in Heikkilä and Piekkola (2005, pages 405–406).

A description of the data can be found at https://taika.stat.fi/en/aineistokuvaus.html#!?dataid=YA246a_19952013_jua_harmonpalrakyks_003.xml

For more details, see Kotilainen (2018, p. 66–69).

The industry classification may be as detailed as the five-digit level.

The number of employees covered by the agreement is available in the documents of the body that decides on the extension of collective agreements.

A few sectors have the option of locally negotiating wages, but in practice local negotiations are very rare because the contracts always have the general increase as a fallback.

The summary statistics are given in Table A3 in the Online Appendix.

References

Addison JT, Teixeira P, Evers K & Kölling A (2017) Changes in bargaining status and intra-plant wage dispersion in Germany. Much ado about nothing? GLO Discussion Paper, No. 24, Global Labor Organization (GLO), Maastricht

Alho KE, Heikkilä A, Lassila J, Pekkarinen J, Piekkola H, Sund R (2003) Suomalainen sopimusjärjestelmätyömarkkinaosapuolten näkemykset. Elinkeinoelämän Tutkimuslaitos B203

Angrist JD, Pischke J-S (2009) Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion. Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press

Blau FD, Kahn LM (1999) Institutions and laws in the labor market. In: ASHENFELTER, O. & CARD, D. (eds.) Handbook of labor economics. Elsevier.

Canal Domínguez JF, Gutiérrez CR (2004) Collective Bargaining and Within-firm Wage Dispersion in Spain. Br J Ind Relat 42:481–506

Card D, De La Rica S (2006) Firm-Level Contracting and the Structure of Wages in Spain. Ind Labor Relat Rev 59:573–592

Cardoso AR, Portugal P (2005) Contractual Wages and the Wage Cushion under Different Bargaining Settings. J Law Econ 23:875–902

Cirillo V, Sostero M, Tamagni F (2019) Firm-level pay agreements and within-firm wage inequalities: Evidence across Europe. In: LEM Working Paper Series, No. 2019/12, Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna, Laboratory of Economics and Management (LEM), Pisa

Dahl CM, Le Maire D, Munch JR (2013) Wage Dispersion and Decentralization of Wage Bargaining. J Law Econ 31:501–533

de Chaisemartin C, d'Haultfoeuille X, Guyonvarch Y (2019) DID_MULTIPLEGT: Stata module to estimate sharp Difference-in-Difference designs with multiple groups and periods. Statistical software components S458643, Boston College Department of Economics. Revised 21 Jul 2023

de Chaisemartin C, d’Haultfoeuille X (2020) Two-way fixed effects estimators with heterogeneous treatment effects. Am Econ Rev 110:2964–2996

Dell’aringa C, Pagani L (2007) Collective bargaining and wage dispersion in Europe. Br J Ind Relat 45:29–54

Fitzenberger B, Kohn K, Lembcke AC (2013) Union Density and Varieties of Coverage: The Anatomy of Union Wage Effects in Germany. Ind Labor Relat Rev 66:169–197

Garnero A (2021) The impact of collective bargaining on employment and wage inequality: Evidence from a new taxonomy of bargaining systems. Eur J Ind Relat 27:187–202

Granqvist L, Regnér H (2008) Decentralized Wage Formation in Sweden. Br J Ind Relat 46:500–520

Gürtzgen N (2016) Estimating the Wage Premium of Collective Wage Contracts: Evidence from Longitudinal Linked Employer-Employee Data. Ind Relat 55:294–322

Heikkilä A, Piekkola H (2005) Explaining the desire for local bargaining: Evidence from a Finnish survey of employers and employees. Labour 19:399–423

Holden S (1998) Wage Drift and the Relevance of Centralised Wage Setting. Scandinavian J Econ 100:711–731

Jonker-Hoffrén P (2019) Finland: goodbye centralised bargaining? The emergence of a new industrial bargaining regime. In: Müller T, Vandaele K, Waddington J (eds) Collective bargaining in Europe: towards an endgame, vol I. ETUI, Brussels, pp 197–116

Kauhanen A, Napari S (2012) Performance measurement and incentive plans. Ind Relat: a J Econ Soc 51:645–669

Kotilainen A (2018) Essays on labor market frictions and wage rigidity. Aalto University publication series. Doctoral dissertations 47/2018

Mcguinnes S, Kelly E, O’Connell PJ (2010) The Impact of Wage Bargaining Regime on Firm-Level Competitiveness and Wage Inequality: The Case of Ireland. Indust Relations: J Econ Soc 49:593–615

OECD (2004) Employment outlook. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/empl_outlook-2004-en

Pekkarinen J, Alho KEO (2005) The finnish bargaining system: Actors' perceptions. In: Piekkola H, Snellman K (eds) Collective bargaining and wage formation. Springer, Heidelberg

Plasman R, Rusinek M, Rycx F (2007) Wages and the bargaining regime under multi-level bargaining: Belgium, Denmark and Spain. Eur J Ind Relat 13:161–180

Ramos R, Sanromá E, Simón H (2022) Collective bargaining levels, employment and wage inequality in Spain. J Policy Model 44:375–395

Rowthorn RE (1992) Centralisation, employment and wage dispersion. Econ J 102:506–523

Rycx F (2003) Industry wage differentials and the bargaining regime in a corporatist country. Int J Manpow 24:347–366

Traxler F (1995) Farewell to labour market associations? Organized versus disorganized decentralization as a map for industrial relations. In: Traxler F, Crouch C (eds) Organized industrial relations in Europe: What future? Aldershot, Avebury, pp 3–19

Visser J (2016) What happened to collective bargaining during the great recession? IZA J Labor Policy 5:9

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Henri Keränen (Labour Institute for Economic Research) and Pekka Vanhala (ETLA Economic Research) for their research assistance and Jed DeVaro and Petri Böckerman for comments. We also thank Annaliina Kotilainen for access to collective bargaining data.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by University of Jyväskylä (JYU). This study was funded by the Finnish Work Environment Fund (no. 190161).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Antti Kauhanen, Terhi Maczulskij and Krista Riukula. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Antti Kauhanen and Terhi Maczulskij and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

N/A

Informed Consent

N/A

Conflict of Interest

Krista Riukula and Antti Kauhanen, Terhi Maczulskij and Krista Riukula declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kauhanen, A., Maczulskij, T. & Riukula, K. The incidence and effects of decentralized wage bargaining in Finland. J Labor Res 45, 232–253 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-024-09356-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-024-09356-x