Abstract

This paper examines how unemployment late in workers’ careers affects retirement timing. Using data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation from 1996 to 2011, we document that unemployed workers permanently leave the labor force at a significantly higher rate than employed workers. This effect is stronger once workers become eligible for Social Security benefits. The effect of unemployment on retirement early in an unemployment spell is weaker for workers eligible for UI benefits. Unemployed workers, particularly those workers in households with below median wealth, also have a significantly higher rate of early Social Security uptake shortly after turning 62 relative to employed workers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

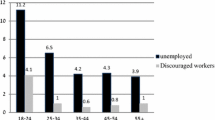

At the end of 2014, the U.S. unemployment rate among workers 55 through 64 years of age was 3.8 %, well below the current national average of 5.6 %. However, the average and median unemployment duration for workers 55 to 64 years of age was 54.6 and 20.5 weeks, respectively, compared to an overall average and median duration of 32.4 and 13.0 weeks, respectively (BLS).

In 2013, 30 % of long-term unemployed were over 50 years of age, while the same age group only made up 20 % of short-term unemployed (Krueger et al. 2014).

Respondents are interviewed three times per year about their experiences over the previous fourth months. Some “core” information is collected at every interview, while other “topical” information is collected less frequently.

We do not restrict the sample further by gender or race but require the topical asset module to have been answered at least once. The results are qualitatively and quantitatively similar for a male only sample.

While the SIPP includes a question on the reason for job loss, the response is missing for about one third of all job losses. Restricting the sample to only those who responded having had an involuntary job loss renders the sample too small for the detailed duration analysis. However, pooling unemployment duration leads to qualitatively similar results between both samples; the monthly retirement hazard for those eligible for early social security benefits is 3.9 percentage points following an involuntary separation, rather than 5.0 percentage points in the sample including all job losses.

The primary reason for grouping into quartiles based on net worth instead of using the raw measure of wealth is that total net worth in the SIPP supplemental questionnaire is underreported, particularly for wealthy households (Czajka et al. 2003).

31.2 % of the individuals in our sample switch wealth quartiles during the interview period. Reassigning these individuals upon switch does not affect the results significantly.

The difference in retirement at age 62 is statistically significant at the 10 % level.

Full (normal) retirement age increased during the sample from 65 if born in 1937 or earlier to 66 if born between 1943 and 1954.

We also include a quadratic polynomial in age and indicator variables for the person being of early (E a r l y S Sage) and full Social Security (F u l l S S a g e) eligibility age. In addition, we include state and time fixed effects and an indicator variable for the nth observation in each panel, which controls for the fact that retirements are more likely to occur later in the panel due to the definition of retirement as exiting the labor force for the rest of the survey. We also include an indicator variable for the start of a new wave to address potential seam-bias problems.

There are two potential concerns in proxying for UI eligibility in this way. First, takeup of government programs is known to be undereported in surveys (e.g. Meyer et al. 2009). The underreporting would cause a downward bias in our estimates. Second, takeup is not random; if individuals with lower job-finding probability and a greater income need are more likely to take up UI, this would bias our estimates upward.

We omit periods with extensions shorter than 99 weeks to focus on the longest possible UI duration and a clear separation relative to the baseline of 26 weeks.

Since the resulting table becomes very difficult to read due to the multitude of interaction terms and since accounting for health coverage does not change our results qualitatively, we present a simple regression table that excludes the duration controls to illustrate the main findings.

We require individuals to start reporting income from Social Security within 6 months of the 62nd birthday. This requires an application for Social Security benefits within 2-3 months of turing 62, at the latest.

We require individuals to start reporting income from Social Security within 6 months of the 62nd birthday. Due to the aforementioned processing time, this requires an application for Social Security benefits within 2–3 months of turing 62, at the latest.

References

Benítez-Silva H, García-Pérez JI, Jiménez-Martín S (2012) The effects of employment uncertainty and wealth shocks on the labor supply and claiming behavior of older American workers. Working Paper.

Benítez-Silva H, García-Pérez JI, Jiménez-Martín S (2014) Reforming the U.S. Social Security system accounting for employment uncertainty. Working Paper

Chan S, Stevens AH (1999) Employment and retirement following a late-career job loss. Am Econ Rev 89(2):211–216

Chan S, Stevens AH (2001) Job loss and employment patterns of older workers. J Labor Econ 19(2):484–521

Chan S, Stevens AH (2004) How does job loss affect the timing of retirement? B.E. J Econ Anal Policy 3(1):1–26

Coile CC, Levine PB (2007) Labor market shocks and retirement: do government programs matter? J Public Econ 91(10):1902–1919

Coile CC, Levine PB (2011a) The market crash and mass layoffs: how the current economic crisis may affect retirement. B.E. J Econ Anal Policy 11(1):1–42

Coile CC, Levine PB (2011b) Recessions, retirement and social security. Am Econ Rev 101(3):23– 28

Czajka JL, Jacobson JE, Cody S (2003) Survey estimates of wealth: a comparative analysis and review of the survey of income and program participation. Mathematica Policy Research, Inc, Washington. Document No. PR03-45

Farber H (2005) What do we know about Job Loss in the United States? Evidence from the Displaced Workers Survey, 1981-2004. Economic Perspectives, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, QII, pp 13–28

Fujita S (2013) On the causes of declines in the labor force participation rate. Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, Research Rap

Garcia-Perez JI, Jimenez-Martin S, Sanchez-Martin AR (2013) Retirement incentives, individual heterogeneity and labor transitions of employed and unemployed workers. Labour Econ 20:106–120

Goda GS, Shoven JB, Slavov SN (2011) What explains changes in retirement plans during the great recession? Am Econ Rev 101(3):29–34

Gustman AL, Steinmeier TL, Tabatabai N (2011) How did the recession of 2007–2009 affect the wealth and retirement of the near retirement age population in the health and retirement study? NBER Working Paper No. 17547

Johnson RW (2011) Mommaerts, C, Age differences in job loss, job search, and reemployment. Urban Institute Discussion Paper

Kroft K, Lange F, Notowidigdo MJ, Katz LF (2014) Long-term unemployment and the great recession: the role of composition, duration dependence and non-participation. Working Paper

Krueger AB, Cramer J, Cho D (2014) Are the long-term unemployed on the margins of the labor market? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity

Meyer BD, Mok WKC, Sullivan JX (2009) The under-reporting of transfers in household surveys: its nature and consequences. NBER Working Paper No. 15181

Rogowski J, Karoly L (2000) Health insurance and retirement behavior: evidence from the health and retirement survey. J Health Econ 19(4):529–539

Tatsiramos K (2010) Job displacement and the transitions to re-employment and early retirement for non-employed older workers. Eur Econ Rev 54(4):517–535

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marmora, P., Ritter, M. Unemployment and the Retirement Decisions of Older Workers. J Labor Res 36, 274–290 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-015-9207-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-015-9207-y