Abstract

The main objective of this study was to understand the relationship between pornography consumption and attitudes toward sexual consent. The study included 1329 adults who answered a sociodemographic questionnaire, questions about pornography consumption, Paraphilic Pornography Consumption Scale, Sexual Consent Scale, and questions about the use of verbal and non-verbal sexual consent behaviors. The results indicate that participants who don’t watch pornography have more positive attitudes towards sexual consent and those that watch pornography every day tend to feel more uncomfortable asking or giving sexual consent. Additionally, there were no gender differences in the way of giving or asking for sexual consent. Our findings acknowledge that pornography has an impact in the attitudes and behaviors of sexual consent, which reinforces the importance of mentioning its impact in sexual education classes. Sexual consent education is a fundamental part of sexual education, and in a digital world where pornography is just a click away, we need to further explore how this relationship can negatively impact people’s sexual experiences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There seems to be an overall agreement that open communication is fundamental to healthy relationships, in order to avoid misunderstandings and provide emotional transparency from each partner. If so, then why do people, when it comes to sexual relationships, tend to assume everything “just happens” and “just go with the flow”? Understanding what a partner wants in a sexual context can be intricate and asking them directly is still perceived as a taboo, which makes asking and giving sexual consent a very complex task. The concept of sexual consent does not yet seem to have a completely clear definition, which translates into very limited research on the subject (Beres et al., 2004; Jozkowski & Peterson, 2013; Jozkowski et al., 2014). There are multiple definitions of sexual consent, such as a mental act, a physical act, an act of moral transformation or, in a more inclusive definition, “the communication of a feeling of will” (Beres, 2007; Hickman & Muehlenhard, 1999). It is important to understand the internal feelings associated with the willingness to engage in sexual activities, as it is possible for someone to engage in consensual sex that they do not want (compliant sex), and, on the other hand, to wish to have sexual intercourse, but to not consent to it (token resistance) (Peterson & Muehlenhard, 2007). Hall (1998) states that sexual consent may be any expression of agreement in having sex, however, unlike Dripps (1992), he affirms that it is necessary to be given freely, either verbally or non-verbally. Social factors may influence the initiation of sexual activity (e.g., peer pressure, gender stereotypes) as a form of social coercion which, in turn, may imply the impossibility of consent. Nevertheless, this argument is rebutted by conceptualizing sexual consent as something not imposed by interpersonal coercion and, therefore, excluding social influences (West, 2002). Consequently, it is necessary to admit the complexity of the theme and how sexual consent is more than a simple “yes” to a certain person, in a certain place, at a certain time, but is also an act with various social expectations (Beres, 2007). Recent feminist research has also been focusing on affirmative consent policies, that have proven to be useful in promoting verbal consent, enthusiasm, and the freedom to say ‘no” (Metz et al., 2021). Affirmative consent programs state that consent can be revoked at any time and the existence of a dating relationship between the persons involved, or past sexual relations between them, should never by itself be assumed as an indicator of consent (Metz et al., 2021). Based on the intertwinement of definitions made by previous literature, the present study considers sexual consent as any expression (verbal or non-verbal) of agreement in having sexual intercourse, in the absence of force, coercion, or threats.

Studies have shown that permission for sexual activity is often given through behaviors such as gaze, body movement, kissing, increased physical proximity, intimate touch, and, less often, smiling (Hall, 1998; Jozkowski, 2011). Research has also shown that non-verbal behaviors are used more often than verbal behaviors to communicate consent, both in heterosexual and homosexual couples, but that the more intimate the behavior, the greater the probability of consent being given verbally (Beres et al., 2004; Fantasia, 2011; Hall, 1998; Hickman & Muehlenhard, 1999; Humphreys, 2005; Humphreys & Herold, 2007; Willis et al., 2021).

But why are people so reluctant to use verbal cues when expressing sexual consent? Some studies reported several reasons, namely because: (i) people consider it embarrassing; (ii) the social norms state that we should not talk about sex; (iii) verbal communication is perceived as lack of spontaneity and romanticism; and (iv) there is a lack of representation of explicit communication in the media (Curtis & Burnett, 2017; Humphreys & Herold, 2003). Thus, there are a lot of social influences undermining the importance of explicit verbal cues in the context of sexual relationships. In addition, Jozkowski and collaborators (2014) claimed that sexual consent is a highly gendered issue, and their results go according to the traditional sexual script. The sexual script theory was introduced by Simon and Gagnon (1986) and refers to sexual behaviors being shaped due to societal settings and expectations, and that they vary greatly depending on cultural factors and the gender of the person executing those behaviors. Since learning about sexuality occurs through socialization, people tend to follow the “scripts” that they learned are more appropriate and expected of them (Simon & Gagnon, 1986). For example, men are expected to always want to engage in sexual relations, and women are viewed as “sexual gatekeepers”, meaning they are the ones who decide whether there will be sexual relations or not (Jozkowski, 2011; Gagnon & Simon, 2003). Thus, while men feel less inhibited about their internalized feelings regarding sexual consent, for women consent can be an ambiguous and complex act. This may be because they are expected to be sensual (Armstrong et al., 2006), or they will be judged for engaging in too many sexual encounters, due to the sexual double standard (Kim et al., 2007). Jozkowski (2011) concluded that women are more likely than men to indicate verbal consent, especially after the partner questions their interest in engaging in sexual activity. However, other studies conclude that men are more likely than women to use explicit verbal cues in sexual consent (Jozkowski et al., 2014; Willis et al., 2019). Finally, some studies claim that men and women give non-verbal consent in a similar way, showcasing the lack of consensus on this topic in current literature (Fegley, 2013; Jozkowski et al., 2019).

The way sexual consent is displayed is not only influenced by social expectations and gender norms. Factors like the type of sexual relationship itself can play a fundamental part. Some researchers claim that individuals in committed relationships use non-verbal cues more often than in recent or casual relationships (Jozkowski et al., 2019; Marcantonio et al., 2018). One possible explanation is that individuals in committed relationships speculate what their partners want because they have a better understanding of who their partners are, and do not feel the need to always ask them for consent (Willis et al., 2021). On the other hand, some research concludes that individuals tend to use more non-verbal communication in situations of sexual intercourse with casual partners, compared to partners in serious relationships, possibly because they feel less comfortable having open communication with someone who they do not have romantic feelings with and have a higher fear of rejection (Foubert et al., 2006; Righi et al., 2019). In addition, some researchers have concluded that the type of relationship people are in does not influence the way they externally express their sexual consent (Freitas, 2017). Thus, we can confirm that the findings regarding the influence of the type of relationship on the behaviors used to give sexual consent are somewhat contradictory.

Sexual Consent and Pornography Consumption

According to the Theory of Cultivation (Gerbner, 1969), the perceptions of reality are cultivated through the observation of the media, and the longer we observe fictional realities, the more we believe that these scenarios reflect the current reality (Gerbner et al., 2002). This is also reinforced by the Sexual Script Theory, which argued that sexual scripts can be formed, changed, or reinforced by various social contexts, such as family, education, and the media (Gagnon & Simon, 2003). Since the media normalizes the use of non-verbal and implicit behaviors in the act of consent, that may influence the audience’s beliefs and, consequently, their sexual behaviors (Brown, 2002; Freitas, 2017). Nowadays, non-verbal clues dominate the representation of consent in mainstream films and since social media is a source of learning and observation of sexual behavior, especially for younger people, that can have an outstanding impact in how people approach consent (Brown, 2002; Jozkowski et al., 2019). If mainstream media content, such as movies and tv shows, can have an impact on how people behave, what are the consequences of viewing explicit sexual content?

Pornography consumption has been growing exponentially, especially due to the accessibility provided by the Internet (Greenfield, 2004; Löfgren-Mårtenson & Månsson, 2010; Luder et al., 2011; Peter & Valkenburg, 2008). The concept of pornography has several definitions, however, the present study identifies it as “representations of written nudity and sexual behavior, in image or audiovisual format” (Silva, 2018) that are “intended to increase arousal” (Morgan, 2011; Mckee et al., 2020). On one hand, some researchers suggest that pornography consumption has no impact on attitudes about sexual behaviors (Linz et al., 1988; Löfgren-Mårtenson & Månsson, 2010; McKee, 2007). However, other studies have shown that the most popular pornographic videos, in general, contained high levels of physical and verbal aggression which produces a negative effect on the thoughts, attitudes, and behaviors of those who observe them (Bridges et al., 2010; Mulac et al., 2002; Jansma et al., 1997). In addition, the majority of those who perpetuated violence in the videos were men, and the targets, showing pleasure or responding neutrally to the aggression, were mostly women (Bridges et al., 2010). Thus, those who consume mainstream pornography are possibly learning that aggression during a sexual encounter is considered normal and may bring pleasure to partners, which produces negative consequences in the conduct of sexual consent in their own relationships (Bridges et al., 2010; Fritz & Paul, 2017).

Paraphilic pornography is described by Hald and Štulhofer (2015) as non-mainstream pornographic content where sexual excitement relies on unusual sexual behaviors that fall in the categories of sadomasochism, fetishism, and violent sex (Stefanska et al., 2022). Literature reports that people who view paraphilic pornography are more likely to accept rape myths and are less likely to intervene in a situation of sexual violence, suggesting that the type of pornography may influence the understanding of reciprocal relationships and, consequently, sexual consent (Brosi et al., 2011). However, it is also important to note that research has shown some positive aspects of pornography consumption, especially for women, such as developing their sexual vocabulary, learning various sexual practices, and reducing shame around their sexual desire, as well as showing a positive correlation between women’s acceptance of pornography and their psychological well-being (Carroll et al., 2008; Parry & Light, 2014).

According to Willis and collaborators (2020), pornography represents subtle sexual scripts regarding the communication of sexual consent, such as “verbal consent is not natural”, “women are indirect, while men are direct”, “sex can occur without constant communication” and “people who receive sexual behaviors can consent by doing nothing”. However, no study has yet explored the relationship between attitudes towards sexual consent and viewing pornography. Therefore, the main objective of the study is to examine the relationship between pornography consumption and sexual consent. The secondary aims of the study are to investigate: (a) gender differences regarding sexual consent behaviors; (b) differences in sexual consent behaviors depending on the type of relationship and (c) the relationship between paraphilic pornography consumption and sexual consent. The hypotheses of the study are as follows: (a) Individuals that consume more pornography have less positive attitudes about sexual consent; (b) Men use more verbal and explicit sexual consent clues than women because, even though there is no consistency in the literature regarding gender difference in the use of verbal behaviors in sexual consent, some recent studies point into this direction (Jozkowski et al., 2014; Willis et al., 2019); (c) Individuals in serious relationships are more likely to use non-verbal sexual consent cues than people in casual relationships as although there are also no consistency in several studies on this topic, recent literature point into this direction (Jozkowski et al., 2019; Marcantonio et al., 2018); (d) Individuals who consume paraphilic pornography are less likely to have positive attitudes about sexual consent than individuals who do not consume this type of pornography, as previous research has shown that aggressive pornography seems to have a negative impact in the viewers attitude and behavior towards sexual relationships (Brosi et al., 2011; Malamuth et al., 2012).

Method

Participants

Our sample consisted of 1329 adults (340 men, 962 women and 27 non-binary) with an average age of 26.79 years (DP = 7.24, minimum = 18, maximum = 78). Most of the participants identified as heterosexual (n = 1074; 82.4%), are Portuguese (n = 1261; 96.7%), employed (n = 624; 47.9%) and with a bachelor’s degree (n = 582; 44.6%). The majority of them had started their sexual activity (n = 1151; 89.3%), had sexual intercourse three or more times in the last month (n = 567; 51.6%) and had their last sexual intercourse in the last month (n = 796; 72.7%). Over half of the participants were currently involved in an intimate relationship (n = 885; 71.7%). From those, the majority were in that relationship for at least one year (n = 671; 77.1%), were dating or engaged (n = 466; 53.5%) and approximately half of them were living with their partner (n = 434; 49.8%). When asked about the frequency of pornography consumption, most participants answered they watched “sometimes a year” (n = 383; 38.8%)(Table 1).

Measures

Sociodemographic Questionnaire, Sexual Activity and Relationship Questions. Participants were asked several sociodemographic questions, including gender, age, sexual orientation, nationality, level of education and professional situation. Next, they were asked several questions related to sexual activity, such as: if they have initiated sexual activities with a partner, how frequently they had had sexual intercourse in the last month and when was the last time they had sexual intercourse. Participants were also asked if they were currently in an intimate relationship (e.g., casual relationship, “friends with benefits”, dating, marriage). If they answered “yes” to this question, they were asked to specify the type of relationship, its duration, if they lived with their partner, and how satisfied they were with the relationship.

Pornography Use. Since the main objective involves the frequency of pornography consumption, the study included the following questions: (1) How frequently do you consume pornographic content (for example, in magazines, books, websites)? (Never; Sometimes a year; Sometimes a month; Daily or more than once a day); and (2) How old were you when you first watched pornographic content? (Castro, 2019).

Paraphilic Pornography Use Scale (PPS; Hald & Štulhofer, 2015; translated and validated to Portuguese by Raposo, 2018). The PPS aims to assess paraphilic pornography use, and consists of five factors, namely Sadomasochism, Bondage and dominance, Violent sex, Bizarre/extreme and Fetish. Participants need to indicate how much they viewed each type of paraphilic pornography (total of 5 items) in the last 12 months (0 = Nothing; 1 = A little; 2 = Moderately; 3 = For the most part; 4 = A lot). The scale shows good internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82 (Hald & Štulhofer, 2015) and 0.80 (Raposo, 2018).

Sexual Consent Scale (SCS; Humphreys & Brousseau, 2010; translated and validated to Portuguese by Abreu, 2017). Using a scale that evaluates sexual consent in a comprehensive way was fundamental for our study. Because SCS evaluates the behaviors and attitudes regarding sexual consent, as well as has a validated and translated version for Portuguese, it was the best option for the online questionnaire. It is composed of 39 items that are rated using a Likert-type scale of 7 points, ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 7 (Strongly agree). The items are subdivided into 5 factors: two behavioral (Indirect Consent Behaviors and Awareness of Consent) and three attitudinal factors: (Lack of Perceived Behavioral Control, Positive Attitude toward Establishing Consent, and Sexual Consent Norms). The scale has items such as “I think that verbally asking for sexual consent is awkward” and “I always verbally ask for consent before I initiate a sexual encounter”. The authors of the original scale indicated a good internal consistency value, both for the total scale (α = 0.87) and the subscales: (i) Lack of Perceived Behavioral Control (α = 0.86); (ii) Positive Attitude toward Establishing Consent (α = 0.84); (iii) Indirect Consent Behaviors (α = 0.78); (iv) Sexual Consent Norms (α = 0.67); and (v) Awareness of Consent (α = 0.71). Similarly, the translated scale has good reliability for most of the subscales.

The use of verbal and non-verbal behaviors in sexual consent. (based on a study conducted by Hickman & Muehlenhard, 1999; translated and validated from Humphreys, 2001). Sexual consent behaviors are very complex to analyze, thus a list of specific verbal and non-verbal consent behaviors helps participants indicate with ease what behaviors they executed most recently. Therefore, the participants were asked to answer a few multiple-choice questions, which have the purpose of measuring how many verbal and non-verbal sexual consent behaviors were used in most recent sexual encounter they had. A few examples of behaviors are: “You undressed yourself”, “You suggested one of you should get a condom” and “You did not say no”. There were total of 37 items (15 examples of non-verbal sexual consent behaviors and 14 verbal sexual consent behaviors). The present study added the options “None of the above” and “Other (please, specify), to obtain a more complete sample of answers.

Procedure

Participants did not receive any monetary compensation and were recruited through institutional emails and online social networks (e.g., Facebook). Participants’ responses were recorded anonymously on an Internet webpage using Qualtrics software, Version 2021 of the Qualtrics Research Suite. The online questionnaire was self-administered and for all participants, sociodemographic, sexual activity and relationship questions were presented first. Regarding the sociodemographic questions, the participants were asked what gender they identified with, given the possibilities “Female”, “Male”, “Non-binary” and “Other – please specify”, the last one being an open-ended question. The age of the participants was asked in a close-ended question, where they typed a number. The participant’s sexual orientation was asked with the following multiple-choice question: “What is your sexual orientation?” and were given the options “Heterosexual”; “Homosexual”, “Bisexual”, “Asexual” and “Other – please specify”, the last one being an open-ended question. The nationality (“Portuguese”, “Brazilian”, “Other – please specify”), level of education (“Elementary School”, “Middle School”, “High School”, “Bachelor”, “Master”, “PhD”, “Other – please specify”), and professional situation (“Student”, “Working-student”, “Worker”, “Unemployed”, “Retired” and “Other – please specify”), were also multiple-choice questions. Then, they answered to questions about pornography consumption, PPC, SCS and questions on the use of verbal and non-verbal behaviors to obtain consent, in a counterbalanced order. The questionnaire was approved by the Ethic Committee of the University of Minho, Portugal.

Data Analysis

All collected data were exported to an Excel spreadsheet. Analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS; v. 27) and included: (i) Descriptive analysis; (ii) Pearson’s correlations to examine the association between the different variables; (iii) Univariate analyses of variance (ANOVA) to compare individuals with different types of relationship, relationship lengths and pornography consumption frequencies. A criterion of p < .05 was used for significance tests.

Results

Gender and Sexual Consent Behaviors

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for the variables used, separately for male and female participants. Independent sample t tests showed that there are statistically significant differences between male and female participants. More specifically, male participants started to watch pornographic materials earlier (M = 13.23; SD = 2.21) than female participants (M = 15.83; SD = 3.99), t(641.16) = -10.62, p < .001. In addition, male participants tend to consume more Paraphilic Pornography (M = 1.48; SD = 0.63) than female participants (M = 1.33; SD = 0.53), t(398.23) = 2.92, p = .001. Results also showed that male participants have a tendency to score higher on the subscale Sexual Consent Norms (M = 4.29; SD = 1.10) than female participants (Msex_con_norms = 3.80; SDsex_con_norms = 1.14), t(286.82) = 3.08, p < .001 and t(749) = 5.18, p < .001, respectively. Similarly, males scored higher on the subscale Awareness and Discussion (M = 4.94; SD = 1.58) than females (M = 4.68; SD = 1.69), t(749) = 1.87, p = .031. However, results showed that female participants tend to score higher on the Positive Attitudes subscale (M = 5.54; SD = 1.07) than males (M = 5.16; SD = 1.14), t(749) = -4.11, p < .001.

Paraphilic Pornography Consumption and Sexual Consent

We examined correlations between Paraphilic pornography, sexual consent subscales (Lack of) perceived behavioral control, Positive attitudes toward establishing consent, Sexual consent norms, Awareness and discussion, Indirect behaviors, Verbal consent behaviors used in their last sexual intercourse, Non-verbal consent behaviors used in their last sexual intercourse, relationship satisfaction, and age of the first exposure to pornography. Results are shown in Table 3.

Paraphilic pornography consumption was positively correlated with Non-verbal consent behaviors (r = .094, p = .025) and negatively correlated with age of first exposure to pornography (r = − .236, p = .000) and relationship satisfaction (r = − .104, p = .024). Thus, individuals who view more paraphilic pornography tend to use more non-verbal consent behaviors, started viewing pornography at a younger age, and report lower relationship satisfaction.

(Lack of) perceived behavioral control was positively correlated with Sexual consent norms (r = .224, p = .000) and Indirect behaviors (r = .141, p = .000). In addition, (Lack of) perceived behavioral control was negatively correlated with Positive attitudes (r = − .433, p = .000), Awareness and discussion about sexual consent (r = − .320, p = .000), Non-verbal consent behaviors (r = − .095, p = .009), Verbal consent behaviors (r = − .238, p = .000), and relationship satisfaction (r = − .332, p < .001). These results suggest that individuals that perceive expressing sexual consent as a difficult task tend to have more social norms about sexual consent, to use more indirect sexual consent behaviors, to have fewer positive attitudes towards sexual consent, to discuss sexual consent less, to report using fewer non-verbal or verbal consent behaviors in their last sexual encounter and have lower relationship satisfaction.

Positive attitudes toward establishing consent was positively correlated with Awareness and discussion (r = .385, p = .000) and Verbal consent behaviors (r = .258, p = .000) and negatively correlated with Sexual consent norms (r = − .267, p = .000) and Indirect behaviors (r = − .169, p = .000). This indicates that individuals who have more positive attitudes towards sexual consent tend to discuss it more with their peers and partners, to use more verbal sexual consent behaviors in their last sexual encounter, to have fewer social norms about sexual consent, and to use less indirect behaviors.

Sexual consent norms was positively correlated with Indirect behaviors (r = .396, p = .000). On the other hand, Sexual consent norms was negatively correlated with Awareness and discussion (r = − .224, p = .000) and Verbal consent behaviors (r = − .091, p = .012). This shows that participants that have higher social norms about sexual consent, use more indirect behaviors, discuss sexual consent less frequently and reported using less verbal consent behaviors in their last sexual encounter.

Awareness and Discussion was positively correlated with Non-verbal consent behaviors (r = .115, p = .001) and Verbal consent behaviors (r = .259, p = .000). On the other hand, it was negatively correlated with Indirect behaviors (r = − .161, p = .000) and age of first exposure to pornography (r = − .109, p = .014). These results suggest that individuals that discuss sexual consent regularly with peers and partners tend to use less indirect behaviors, to have started consuming pornography at a younger age, and use more verbal and non-verbal behaviors of sexual consent in their most recent sexual encounter.

The scale Indirect behaviors was positively correlated with Non-verbal consent behaviors (r = .114, p = .001) and relationship satisfaction (r = .089, p = .028), and negatively correlated with Verbal consent behaviors (r = − .154, p = .000). These results indicate that participants that mention they use more indirect behaviors to indicate sexual consent, reported using more non-verbal behaviors in their last sexual encounter, tend to have higher relationship satisfaction and used fewer verbal sexual consent behaviors in their last sexual encounter.

Non-verbal consent behaviors was positively correlated with Verbal consent behaviors (r = .353, p = .000), showing that individuals who use more non-verbal consent behaviors, also tend to use more verbal consent behaviors in their last sexual encounter.

Finally, Verbal consent behaviors was positively correlated with relationship satisfaction (r = .172, p = .000). This shows that people who use more verbal consent behaviors in their last sexual encounter tend to be more satisfied with their relationship.

Type of Relationship and Sexual Consent

A one-way ANOVA showed a main effect of relationship satisfaction, F (3, 857) = 26.37, p <0.001.

Post Hoc Tukey tests showed that participants that were in casual relationships or friends with benefits were less satisfied with their relationship (M = 5.11; SD = 1.28) than participants that were dating or engaged (M = 6.19; SD = 1.066) or were in a polyamorous relationship (M = 6.15; SD = 1.05), p < .001 and p < .001. Results also showed a main effect of Indirect behaviors, F (3, 610) = 2.93, p = .033. Post Hoc Tukey tests showed that participants that were in casual relationships or friends with benefits used less Indirect behaviors (M = 4.75; SD = 1.01) than participants in a polyamorous relationship (M = 5.16; SD = 1.03), p = .027. In addition, results showed a main effect of Awareness and discussion, F (3, 610) = 4.03, p = .007. Post Hoc Tukey tests showed that participants in a polyamorous relationship tended to discuss sexual consent less with their peers (M = 4.41; SD = 1.746) than participants that were in casual relationships or friends with benefits (M = 5.08; SD = 1.57) and that were married or in a non-marital partnership (M = 5.33; SD = 2.18), p = .023 and p = .038, respectively.

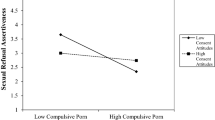

Finally, our data showed a main effect of using Non-verbal consent behaviors in their most recent sexual encounter, F (3, 711) = 4.04, p = .007. Post Hoc Tukey tests showed that participants that were in casual relationships or friends with benefits tended to use more Non-verbal behaviors (M = 7.66; SD = 3.66) than participants in a polyamorous relationship (M = 6.27; SD = 2.98), p = .005. (see Fig. 1)

Relationship Length

A one-way ANOVA showed a main effect of using Non-verbal consent behaviors in their most recent sexual encounter, F (3, 710) = 4.97, p = .002. Post Hoc Tukey tests showed that participants that have been in a relationship for less than six months tend to use more Non-verbal behaviors (M = 7.61; SD = 3.49) than participants that have been in a relationship between one and five years (M = 6.57; SD = 2.98) and that have been in a relationship for more than five years (M = 6.34; SD = 3.05), p = .031 and p = .005, respectively.

Pornography Consumption and Sexual Consent

A one-way ANOVA showed a main effect of relationship satisfaction, F (3, 707) = 5.20, p = .001. Post Hoc Tukey tests showed that participants that watch pornography approximately a couple times a month tend to be less satisfied with their relationship (M = 5.73; SD = 0.1.25) than participants that do not watch pornography (M = 6.17; SD = 1.19) and those that watch only a couple times a year (M = 6.09; SD = 1.03), p = .001 and p = .007, respectively. Results also showed a main effect of (Lack of) perceived behavioral control, F (3,753) = 3.89, p = .009. Post Hoc Tukey tests showed that participants that watch pornography every day or more than once a day tend to be more uncomfortable asking or giving sexual consent (M = 2.12; SD = 0.99) than participants that watch pornography a couple of times a year (M = 1.72; SD = 0.84), p = .042. Moreover, our data showed a main effect of Positive attitudes, F (3, 753) = 5.64, p < .001. Post Hoc Tukey tests suggested that participants that do not watch pornography tend to have more positive attitudes toward sexual consent (M = 5.47; SD = 1.09) than participants that watch pornography every day or more than once a day (M = 4.94; SD = 1.41), p = .035. In addition, participants that watch pornography a couple of times a year tend to have more positive attitudes toward sexual consent (M = 5.59; SD = 0.98) compared with participants that watch it a couple of times a month (M = 4.29; SD = 1.17) and with those that watch it every day or more than once a day, p = .017 and p = .004, respectively.

Results also showed a main effect of Sexual consent norms, F (3, 753) = 3.09, p = .027. Post. Hoc Tukey tests indicated that participants that do not watch pornography tend to have lower assumptions about sexual consent (M = 3.76; SD = 1.19) than participants that watch pornography a couple times a month (M = 4.05; SD = 1.21), p = .050. (see Fig. 2)

Regression Analysis Predicting Positive Attitudes Towards Sexual Consent

We performed multiple regression analyses wherein the frequency of pornography consumption was regressed onto seven predictor variables. On Table 4 it is possible to see that the model measured the variables collectively explained approximately 30% of the total variance in Positive attitudes towards sexual consent (29.9%). The standardized regression coefficients (βs) for the specific variables indicated that gender, Verbal consent behaviors, (Lack of) perceived control, Sexual consent norms, Awareness and discussion, and Verbal consent behaviors were the strongest and unique predictors of Positive attitudes towards sexual consent. These patterns support the deduction that gender, Verbal consent behaviors, (Lack of) perceived control, Sexual consent norms, Awareness and discussion, and Verbal consent behaviors were strong and unique predictors of Positive attitudes towards sexual consent.

Discussion

Compared to the literature related to sexual assault, there is a lack of empirical work on the communication of sexual consent, which is fundamental for a better understanding of sexual violence (Beres, 2007). In addition, the study of consent is important from the perspective of normative situations, since sexual communication is significantly correlated with relationship satisfaction (Timm & Keiley, 2011; Vannier & O’Sullivan, 2011). The consumption of pornography may have a negative impact in the viewers’ sexual activities being as though, in mainstream pornography, scenes with positive behaviors are significantly less frequent compared to those that contain aggression (Donnerstein et al., 1987; Bridges et al., 2010). Thus, in addition to the lack of studies related to sexual consent, there is also a lack of research on pornography’s role in peoples’ sexual consent attitudes (Fegley, 2013; Terán & Dajches, 2020). The focus of this study was pornography consumption’s influence on sexual consent attitudes and behaviors, while also investigating the relationship between sexual consent and paraphilic pornography consumption. Furthermore, we explored some inconsistencies in current literature, such as the influence of gender and type of relationship in sexual consent behaviors.

Results showed that participants that watch pornography every day or more than once a day tend to perceive they had less control in asking for sexual consent than those that do not watch it that often, i.e., they feel less comfortable communicating directly about what they (or their partner) want, due to a fear of possible negative reactions, such as feeling awkward or “spoiling the mood” (Humphreys & Brousseau, 2010; Humphreys, 2004). Results also showed that participants that do not watch pornography tend to have more positive attitudes toward sexual consent than those that watch it every day or more than once a day. These results are consistent with the first hypothesis: individuals that consume more pornography have fewer positive attitudes about sexual consent. Our data suggest that participants that do not watch pornography give higher importance to negotiating consent verbally and disagree that consent can be assumed, thus fighting the narrative often propagated by pornography, such as “verbal consent is not natural”, and that “sex can occur without constant communication” (Humphreys & Brousseau, 2010; Willis et al., 2020). Our results also support Terán and Dajches’s (2020) research, that pornography’s risk and lack of responsibility messages may persuade the viewers that refusing sex is not normal. Additionally, results also indicate that people who watch pornography every day or more than once a day think that sexual consent is more important in certain activities rather than all sexual activities and do not acknowledge that consent needs to be discussed even if during a single encounter, which is consistent with the inaccurate depictions of sexual consent in pornography (Willis et al., 2020).

Within the context of gender, our results showed that men perceived they had less control in asking for sexual consent, had less positive attitudes, and more perceived social norms about sexual consent than women. However, men showed a higher value of awareness and discussion about sexual consent than women, meaning that they tend to discuss it with partners and friends more, compared to women, which was an unexpected find. In addition, there were no statistically significant differences between the use of non-verbal behaviors in sexual consent between men and women, which is not consistent with our second hypothesis, where we supposed that men use more verbal and explicit sexual consent clues than women. However, our results go accordantly with Fegley’ research (2013), that suggest that men and women use non-verbal consent cues equally, both being influenced by the existing social norms. The present study goes one step further by analyzing the relationship between positive attitudes related to sexual consent and gender. Given that men have fewer positive attitudes towards sexual consent, it is possible that gender differences may not be noted through behaviors, but rather attitudes and thoughts regarding sexual consent. A recent study by Benoit and Ronis (2022) found that women did not know that it was acceptable to withdraw consent or were unsure of how to do so, and when they did, the frequent response of male partners was to insist. This often led to a case of compliance by women, where they agreed to sexual activity without having the desire to do so (Benoit & Ronis, 2022). Thus, it is possible that despite the fact that both men and women are being influenced by societal norms that it is not very acceptable to use verbal consent, women continue to place more importance on consent compared to men for various reasons. It may be because of women’s expression of their sexuality being influenced by certain sexual scripts that are expected to be followed, for example, women being seen as sexual gatekeepers or expected to take a more passive role in sexual relationships; or because of unbalanced power dynamics that lead them to not being able to assertively express their sexual desires. Since negotiations of affirmative consent are influenced by these sexual double standards and gender norms, it is crucial to work to disrupt those scripts and find new ways to educate men in order to promote consensual sexual intimacy (Metz et al., 2021). Thus, women value the communication of consent more than men, possibly because it would be a way to counter what is expected of them, according to the traditional sexual script, thus allowing a more liberated sexual expression. That being said, gender remains an important construct to consider in future sexual consent research (Willis et al., 2021).

Results showed that there was no significant difference in the use of verbal or non-verbal behaviors to indicate sexual consent between people in serious relationships (dating or engaged) versus people in casual relationships or friends with benefits, which is inconsistent with our third hypothesis. After analyzing previous articles, we can conclude that there is not much consensus on how the type of relationship can influence how sexual consent is given (Freitas, 2017). Our data ads to the research on sexual consent, since the only previous study that found no influence on the type of relationship and the way people externally express their sexual consent, used a sample of only female participants (Freitas, 2017). Additionally, the results show that individuals that are in casual relationships or friends with benefits tend to score lower in the subscale indirect behaviors than participants in a polyamorous relationship but used more non-verbal behaviors in their last sexual relationship than participants in a polyamorous relationship. It is important to note that a main difference between these two types of relationships is that one has emotional and romantic implications, whereas the other does not (Klesse, 2006). Although our data may seem contradictory, the subscale indirect behaviors evaluate the importance given to the use of direct behaviors in sexual consent (e.g., “I don’t have to ask or give my partner sexual consent because my partner knows me well enough”), while the other questions how many non-verbal behaviors were used in the last sexual relationship (e.g., “I kissed my partner.”). Thus, results suggest that individuals in casual relationships give more importance to verbal sexual communication than people in polyamorous relationships and, in their last sexual relationship, they used more non-verbal sexual behaviors than polyamorous individuals, which does not diminish the importance casual partners give to verbal sexual behaviors. Since there is scarce literature comparing sexual consent behaviors of casual vs. polyamorous relationships, it would be interesting for future investigations to specifically explore these dynamics.

Since consent became the key criterion for distinguishing normal sexual activity from pathological and criminal forms, it is important to understand the relationship between paraphilic pornography and sexual consent (Giami, 2015; Stefanska et al., 2022). Results did not show a statistically significant relationship between paraphilic pornography consumption and positive attitudes towards sexual consent, which is inconsistent with our fifth hypothesis. This result suggests that consuming paraphilic pornography does not impact attitudes towards sexual consent, perhaps because the impact would only be present if the participant themselves executed paraphilic sexual behavior. This is true, for example, in the case of BDSM, where changes in perspectives regarding sexual consent were only significant after practicing BDSM behaviors, and not just viewing pornography with that type of content (Abreu, 2017).

Our study has some limitations that should be acknowledge. First, most of the participants were women, and since men are typically the gender that consumes more pornography, it would have been important to have more male participants. Secondly, pornography co-viewing was not evaluated, and since there is evidence to suggest that some women co-view pornography at their partner’s request, potentially out of a sense of compliance rather than genuine interest, it would have been an interesting factor to explore. Also, if high consumption of pornography is co-viewed with their partner, perhaps the participants don’t explicitly seek consent because they assume that they are in agreement with their partner, especially if they had recently viewed the sexual acts together. These circumstances surrounding pornography consumption are important factors that should be considered in future research. In addition, since it was used self-report measures, the participants responses could have been influenced by non-controlling factors. These factors already acknowledged by the original scales’ authors, could be social desirability (due to the theme of the study), a predisposition to answer the questionnaire (since the participants were self-selected), tiredness (from answering the questionnaire) and distraction. Additionally, specifically regarding the Sexual Consent Scale (SCS; Humphreys & Brousseau, 2010) some items could be interpreted ambiguously as either referring to general sexual consent or verbal sexual consent, thus needing a careful analysis. Given the extension of the data analyses and the lower representation of non-heterosexual individuals, it was not possible to analyze the data gathered from that population. We understand this as a limitation of our study to represent participants of all sexual orientations and future research should take that into consideration. Finally, because it was a convenience sample, the participants were recruited through social networks (Facebook and Instagram), and thus we advise caution generalizing the results. In addition, Facebook and Instagram are visual social media platforms, thus users might have visual predilections to begin with.

The impact of pornography consumption has been related to numerous negative consequences of sexual behavior, such as sexually deviant tendencies, an increased risk of committing sexual offenses, endorsement of rape myths, and sexual harassment of women (Brosi et al., 2011; Lam & Chan, 2007; Paolucci et al., 1997). Fegley (2013) defends that even though pornography can be an appropriate tool for sexual fantasies for many individuals, it should not be considered a model of sexual behavior. Thus, studying the impact that pornography has on sexual consent is fundamental for sex education by acknowledging how consent communication is modeled in pornography and by teaching about pornography literacy, as many young people use pornography as a way of learning sexual acts (Willis et al., 2020). Depending on pornography for sexual education can be a very dangerous thing, given that, according to the present study, a higher frequency of pornography consumption is related to lower positive attitudes towards sexual consent. In summary, how consent is used may vary by context, and it’s important for educators, professionals, investigators, and everyday people to know that communicating consent should not ever be taken for granted (Willis et al., 2019). It is also important to acknowledge the clinical and social implications that this study has, being a tool for therapists to identify risk factors associated with pornography consumption, to address misconceptions about sexual consent to individuals who seek therapy for issues related to sexual behavior or relationships, and to promote affirmative consent. Thus, the study is a valuable contribution to other sexuality studies and sexual assault prevention as it deepens the understanding of sexual consent, its contexts, and the behaviors and attitudes associated with it.

In conclusion, mainstream pornography often portrays a narrative where the question of “Do I really need to ask?” is implicitly answered with a resounding “not really.” As observed in the findings, this portrayal significantly influences individuals’ perceptions and behaviors surrounding consent, leading to a reluctance to explicitly seek or give affirmative consent. Societal norms, media representations, and the pervasive influence of pornography all contribute to this discomfort and “fear of awkwardness” with direct communication about consent. Despite the various influences that perpetuate the notion of “no need to ask,” recent research shows that affirmative consent serves as the pillar of healthy sexual communication. It teaches us that it is always preferable to seek explicit consent rather than make assumptions. It is important to acknowledge the complexities involved, especially in regard of the existing gender norms and the struggles women face in expressing sexual consent due to the imbalanced power dynamics between men and women. Even so, affirming consent represents the essential first step towards fostering a culture of respectful and consensual sexual interactions, fighting against the harmful influences that surround us.

References

Abreu, S. M. (2017). BDSM: no limiar do consentimento sexual. [Tese de Mestrado, Universidade Fernando Pessoa]. Repositório Institucional da Universidade Fernando Pessoa. http://hdl.handle.net/10284/6026.

Armstrong, E. A., Hamilton, L., & Sweeney, B. (2006). Sexual assault on campus: A multilevel integrative approach to party rape. Social Problems, 53(4), 483–499. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2006.53.4.483.

Benoit, A. A., & Ronis, S. T. (2022). A qualitative examination of withdrawing sexual consent, sexual compliance, and young women’s role as sexual gatekeepers. International Journal of Sexual Health, 34(4), 577–592.

Beres, M. A. (2007). ‘Spontaneous’’ sexual consent: An analysis of sexual consent literature. Feminism & Psychology, 17(1), 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353507072914.

Beres, M. A., Herold, E., & Maitland, S. B. (2004). Sexual consent behaviors in same-sex relationships. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 33(5), 475–486. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:ASEB.0000037428.41757.10.

Bridges, A. J., Wosnitzer, R., Scharrer, E., Sun, C., & Liberman, R. (2010). Aggression and sexual behavior in best-selling pornography videos: A content analysis update. Violence against Women, 16(10), 1065–1085. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801210382866.

Brosi, M. W., Foubert, P. D., Bannon, J. D., R. S., & Yandell, G. (2011). Effects of sorority members’ pornography use on bystander intervention in a sexual assault situation and rape myth acceptance. Oracle: The Research Journal of the Association of Fraternity/Sorority Advisors, 6(2), 26–35. https://doi.org/10.25774/60dk-dg51.

Brown, J. D. (2002). Mass media influences on sexuality. Journal of Sex Research, 39(1), 42–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490209552118.

Carroll, J. S., Padilla-Walker, L. M., Nelson, L. J., Olson, C. D., McNamara Barry, C., & Madsen, S. D. (2008). Generation XXX: Pornography acceptance and use among emerging adults. Journal of Adolescent Research, 23(1), 6–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558407306348.

Castro, R. (2019). Valores, atitudes e significados da pornografia: um estudo com uma amostra portuguesa. [Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade do Porto]. Repositório Aberto. https://hdl.handle.net/10216/121035.

Curtis, J. N., & Burnett, S. (2017). Affirmative consent: What do college student leaders think about yes means yes as the standard for sexual behavior? American Journal of Sexuality Education, 12(3), 201–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/15546128.2017.1328322.

Donnerstein, E., Linz, D. G., & Penrod, S. (1987). The question of pornography. The Free.

Dripps, D. (1992). Beyond rape: An essay on the difference between the Presence of Force and the absence of Consent. Columbia Law Review, 92(7), 1780–1809. https://doi.org/10.2307/1123045.

Fantasia, H. C. (2011). Really not even a decision anymore: Late adolescent narratives of implied sexual consent. Journal of Forensic Nursing, 7(3), 120–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-3938.2011.01108.x.

Fegley, H. L. (2013). The danger of assumed realism in pornography: pornography use and its relationship to sexual consent. [Master’s Thesis, Smith College]. Smith ScholarWorks.

Foubert, J. D., Garner, D. N., & Thaxter, P. J. (2006). An exploration of fraternity culture: Implications for programs to address alcohol-related sexual assault. College Student Journal, 40, 361–373.

Freitas, S. F. (2017). A Influência das Cinquenta sombras de Grey no consentimento sexual de estudantes universitárias. [Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade do Porto]. Repositório Aberto. https://hdl.handle.net/10216/105058.

Fritz, N., & Paul, B. (2017). From orgasms to spanking: A content analysis of the agentic and objectifying sexual scripts in feminist, for women, and mainstream pornography. Sex Roles, 77, 639–652. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0759-6.

Gerbner, G. (1969). Toward cultural indicators: The analysis of mass mediated public message systems. AV Communication Review, 17(2), 137–148.

Gerbner, G., Gross, L., Morgan, M., Signorielli, N., & Shanahan, J. (2002). Growing up with television: Cultivation processes. In J. Bryant, & D. Zillmann (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (pp. 43–67). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Giami, A. (2015). Between DSM and ICD: Paraphilias and the transformation of sexual norms. A rchives of Sexual Behavior, 44(5), 1127–1138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0549-6

Greenfield, P. M. (2004). Inadvertent exposure to pornography on the internet: Implications of peer-topeer file-sharing networks for child development and families. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 25(6), 741–750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2004.09.009.

Hald, G. M., & Štulhofer, A. (2015). What types of pornography do people use and do they cluster? assessing types and categories of pornography consumption in a large-scale online sample. Journal of sex research, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2015.1065953.

Hall, D. S. (1998). Consent for sexual behavior in a College Student Population. Electronic Journal of Human Sexuality, 1.

Hickman, S. E., & Muehlenhard, C. L. (1999). By the semi-mystical appearance of a condom: How young women and men communicate sexual consent in heterosexual situations. Journal of Sex Research, 36(3), 258–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499909551996.

Humphreys, T. (2001). Sexual consent in heterosexual dating relationships: Attitudes and behaviours of university students. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 61(12-B), 6760.

Humphreys, T. P. (2005). Understanding sexual consent: An empirical investigation of the normative script for young heterosexual adults. In M. Cowling, & P. Reynolds (Eds.), Making sense of sexual consent (pp. 207–225). Ashgate.

Humphreys, T. P., & Brousseau, M. M. (2010). The sexual consent scale-revised: Development, reliability, and preliminary validity. Journal of sex Research, 47(5), 420–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490903151358.

Humphreys, T. P., & Herold, E. (2003). Should universities and Colleges Mandate sexual behavior? Student perceptions of Antioch College’s Consent Policy. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 15(1), 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1300/J056v15n01_04.

Humphreys, T. P., & Herold, E. (2007). Sexual consent in Heterosexual relationships: Development of a new measure. Sex Roles, 57(3–4), 305–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9264-7.

Jansma, L. L., Linz, D. G., Mulac, A., & Imrich, D. J. (1997). Men’s interactions with women after viewing sexually explicit films: Does degradation make a difference? Communications Monographs, 64, 1–24.

Jozkowski, K. N. (2011). Measuring internal and external conceptualizations of sexual consent: A mixed methods exploration of sexual consent [Doctoral dissertation, Indiana University]. Publicly Available Content Database.

Jozkowski, K. N., & Peterson, Z. D. (2013). College students and sexual consent: Unique insights. Journal of sex Research, 50(6), 517–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2012.700739.

Jozkowski, K. N., Sanders, S., Peterson, Z. D., Dennis, B., & Reece, M. (2014). Consenting to sexual activity: The development and psychometric assessment of dual measures of consent. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(3), 437–450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0225-7.

Jozkowski, K. N., Marcantonio, T. L., Rhoads, K. E., Canan, S., Hunt, M. E., & Willis, M. (2019). A content analysis of sexual consent and refusal communication in mainstream films. The Journal of Sex Research, 56(6), 754–765. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2019.1595503.

Kim, J. L., Sorsoli, C. L., Collins, K., Zylbergold, B. A., Schooler, D., & Tolman, D. (2007). From sex to sexuality: Exposing the heterosexual script on prime-time network television. Journal of Sex Research, 44(2), 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490701263660.

Klesse, C. (2006). Polyamory and its ‘Others’: Contesting the terms of Non-monogamy. Sexualities, 9(5), 565–583. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460706069986.

Linz, D. G., Donnerstein, E., & Penrod, S. (1988). Effects of long-term exposure to violent and sexually degrading depictions of women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55(5), 758–768. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.55.5.758.

Lofgren-Mårtenson, L., & Månsson, S.-A. (2010). Lust, love, and life: A qualitative study of Swedish adolescents’perceptions and experiences with pornography. Journal of Sex Research, 47(6), 568–579. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490903151374

Luder, M. T., Pittet, I., Berchtold, A., Akré, C., Michaud, P. A., & Surís, J. C. (2011). Associations between online pornography and sexual behavior among adolescents: myth or reality? Archives of sexual behavior, 40(5), 1027–1035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-010-9714-0.

Malamuth, N. M., Hald, G. M., & Koss, M. (2012). Pornography, individual differences in risk and men’s acceptance of violence against women in a representative sample. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 66(7–8), 427–439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-0082-6.

Marcantonio, T., Jozkowski, K. N., & Wiersma-Mosley, J. (2018). The Influence of Partner Status and Sexual Behavior on College Women’s Consent Communication and Feelings. Journal of sex & marital therapy, 44(8), 776–786. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2018.1474410.

McKee, A. P. D. (2007). The relationship between attitudes towards women, consumption of Pornography, and other demographic variables in a survey of 1,023 consumers of Pornography. International Journal of Sexual Health, 19(1), 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1300/J514v19n01_05.

McKee, A., Byron, P., Litsou, K., & Ingham, R. (2020). An interdisciplinary definition of Pornography: Results from a global Delphi Panel. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49, 1085–1091. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-01554-4.

Metz, J., Myers, K., & Wallace, P. (2021). Rape is a man’s issue:’gender and power in the era of affirmative sexual consent. Journal of Gender Studies, 30(1), 52–65.

Morgan, E. M. (2011). Associations between young adults’ use of sexually explicit materials and their sexual preferences, behaviors, and satisfaction. Journal of sex Research, 48(6), 520–530.

Mulac, A., Jansma, L. L., & Linz, D. G. (2002). Men’s behavior toward women after viewing sexually-explicit films: Degradation makes a difference. Communication Monographs, 69(4), 311–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750216544.

Paolucci, E. O., Genuis, M., & Violato, C. (1997). A meta-analysis of the published research on the effects of pornography. Medicine Mind and Adolescence, 72(1–2), 48–59.

Parry, D. C., & Light, T. P. (2014). Fifty shades of complexity: Exploring technologically mediated leisure and women’s sexuality. Journal of Leisure Research, 46(1), 38–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2014.11950312.

Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2008). Adolescents’ exposure to sexually explicit internet material and sexual preoccupancy: A three-wave panel study. Media Psychology, 11(2), 207–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213260801994238.

Peterson, Z. D., & Muehlenhard, C. L. (2007). Conceptualizing the ‘‘wantedness’’ of women’s consensual and nonconsensual sexual experiences: Implications for how women label their experiences with rape. Journal of Sex Research, 44(1), 72–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490709336794.

Raposo, E. M. (2018). Relationship between pornography consumption and sexual health [Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade do Porto]. Repositório Aberto. https://hdl.handle.net/10216/116748.

Righi, M. K., Bogen, K. W., Kuo, C., & Orchowski, L. M. (2019). A qualitative analysis of beliefs about sexual consent among high school students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519842855.

Silva, J. (2018). O impacto do consumo de pornografia nas relações de intimidade: Uma revisão teórica. [Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade do Porto].

Simon, W., & Gagnon, J. H. (1986). Sexual scripts: Permanence and change. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 15, 97–120.

Simon, W., & Gagnon, J. H. (2003). Sexual scripts: Origins, influences and changes. Qualitative Sociology, 26(4), 491–497.

Stefanska, E. B., Longpré, N., & Rogerson, H., (2022). Relationship between atypical sexual fantasies, Behavior, and Pornography Consumption. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X221086569. Advance online publication.

Terán, L., & Dajches, L. (2020). The Pornography How-To Script: The moderating role of consent attitudes on pornography consumption and sexual refusal assertiveness. Sexuality & Culture, 24, 2098–2112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-020-09739-z.

Timm, T. M., & Keiley, M. K. (2011). The effects of differentiation of self, adult attachment, and sexualcommunication on sexual and marital satisfaction: A path analysis. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 37(3), 206–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2011.564513

Vannier, S. A., & O’Sullivan, L. F. (2011). Communicating interest in sex: Verbal and nonverbal initiation of sexualactivity in young adults’ romantic dating relationships. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40(5), 961–969. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-010-9663-7

West, R. (2002). The Harms of Consensual Sex. In A. Soble (Ed.), The philosophy of sex: Contemporary readings (pp. 317–322). Rowman and Littlefield.

Willis, M., Hunt, M. E., Wodika, A. B., Rhodes, D. L., Goodman, J., & Jozkowski, K. N. (2019). Explicit verbal sexual Consent communication: Effects of gender, relationship status, and type of sexual behavior. International Journal of Sexual Health, 31, 60–70.

Willis, M., Canan, S. N., Jozkowski, K. N., & Bridges, A. J. (2020). Sexual Consent Communication in Best-Selling Pornography films: A content analysis. Journal of sex Research, 57(1), 52–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2019.1655522.

Willis, M., Murray, K. N., & Jozkowski, K. N. (2021). Sexual consent in Committed relationships: A dyadic study. Journal of sex & Marital Therapy, 47(7), 669–686. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2021.1937417.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Open access funding provided by FCT|FCCN (b-on).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Ana Simão Marques, Joana Arantes, Ana Filipa Braga and Ândria Brito. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Ana Simão Oliveira Roriz Marques and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of University of Minho (CEICSH044/2021).

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to publication

Since there is no personal information being disclosed in this article, asking for consent to publish was not necessary.

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Marques, A.S., Braga, A.F., Brito, Â. et al. “Do I Really Need To Ask?”: Relationship Between Pornography and Sexual Consent. Sexuality & Culture (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-024-10228-w

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-024-10228-w