Abstract

Recent years have seen a rise in research on sexual addiction (SA) and compulsive sexual behaviour (CSB). In the literature, these concepts describe an emerging field of study that may encompass a range of interpersonal and communal consequences for concerned individuals, their intimate partners, families, and society. Taboos surrounding SA/CSB often shroud the subject in shame and ignorance. Despite growing scholarly interest in SA/CSB, few studies have analysed intimate partners’ lived experiences in depth, and no other research has investigated the spiritual impacts of SA/CSB on intimate partners. This descriptive phenomenological study addresses this knowledge gap. In-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with female partners (primary participants; n = 12) and professional counsellors (supplementary participants; n = 15). The analysis reveals that following discovery/disclosure, SA/CSB may affect women via complex and multifaceted spiritual consequences. Significantly, most women did not receive validation or safety from their faith communities. Instead, many reported experiencing a range of spiritual impacts, including changes in their faith, fear of stigmatization, the perception of pastoral pressure to ‘forgive and forget’, ostracism from their faith communities, and/or a sense of anger directed towards God as the perceived silent co-conspirator who permitted the deception to continue undiscovered, sometimes over years or even decades. The study’s findings point to salient opportunities for faith communities to provide more targeted support and assistance during healing and recovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sex and sexuality are a significant part of human spirituality, which in turn is closely linked to mental health and well-being. Consequently, problematic expressions of sexual conduct, i.e., compulsive sexual behaviour (CSB) or so-called sexual addiction (SA), can widely impinge on the spirituality of individuals, partnerships, families, and communities, with far-reaching ripple effects and consequences on society at large (Hastings & Lucero Jones, 2023; Seyed Aghamiri & Luetz, 2021). The literature commonly uses the terms SA and CSB interchangeably to refer to a hypersexual condition that includes compulsive, risky, and uncontrollable sexual behaviours (Grubbs et al., 2020; Reid & Kafka, 2014; Seyed Aghamiri, 2020; WHO, 2019).

Sexual addiction is a behavioural condition that occurs and hinders an individual’s unimpeded daily functioning and impinges on intimate relationships (Carnes & Adams, 2019). It can have multiple negative consequences for individuals, intimate partners, and society as a whole (Grubbs et al., 2020; Reid et al., 2012; Seyed Aghamiri & Luetz, 2021; Seyed Aghamiri et al., 2022a, 2022b). Among these negative outcomes are separation, broken relationships, divorce, lack of interest in partnered intimacy, extramarital affairs, sexual promiscuity, drug abuse, decreased productivity, and mental health impairments, among others (Braun-Courville & Rojas, 2009; Cooper et al., 2000; Schneider, 2000). In addition to intense anger, betrayal, insecurity, indignation, depressive symptoms, anxiety, shame, guilt, jealousy, and grief, the affected partners may also experience other emotional ramifications of SA/CSB-related betrayal (Gossner et al., 2022; Lonergan et al., 2022). Although this field of study is still in its infancy, relatively limited research has shown that SA/CSBs may have social, psychological, and physical repercussions on relationships and intimate partners (Cooper et al., 2000; Carnes, 2018; Steffens & Rennie, 2006; Steffens & Means, 2009, 2017; Seyed Aghamiri & Luetz, 2021; Seyed Aghamiri et al., 2022a, 2022b; Weiss, 2019). Significantly, there is a dearth of comprehensive investigations on the spiritual effects of SA/CSB on intimate partners. Therefore, in the context of this study, the primary focus of this paper is intentionally placed on identifying the spiritual consequences of these behaviours on intimate partners.

Finding out about a significant partner’s concealed SA/CSBs can be upsetting and feel like the ultimate betrayal (Hall, 2016; Weiss, 2020). This is because the experience is intensely held within and can resemble other traumatic occurrences (Schneider et al., 2012; Vogeler et al., 2018). The majority of betrayed partners find it difficult to regulate the turbulent sentiments of shock, confusion, bothersome thoughts and triggers that arise from discovery/disclosure for a long time (Keffer, 2019; Steffens & Means, 2017; Weiss, 2019). As a result, affected partners frequently experience a phenomenon known as betrayal trauma (BT), which is similar to attachment injury, mirrors the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and includes confusion, shock, hypervigilance, and a loss of the ability to perceive the world as safe (Roos et al., 2019; Stokes et al., 2020). There are indications that BT is strongly linked to a person’s spiritual identity and may trigger crises of faith (Weiss, 2021a, 2021b).

Spiritual crises can have a variety of complex and detrimental effects. For instance, the current study discovered that 83% of female intimate partners, even those who self-identified as atheist or agnostic, described being angry at God or a higher power. It appeared they were feeling unfairly treated and upset with God. In addition, women who suffered from BT frequently endured intense grief, which heightened their experience of spiritual crisis. Another factor that contributed to the affected women’s estrangement from God, their ‘higher power’, or their faith-based communities was the experience of pressure to hastily forgive without first holding the offending partner accountable or enforcing boundaries and without any clear validation. Most impacted women experienced a temporary, transient break in their spirituality after experiencing BT, with some experiencing a permanent loss while others discovered a new spirituality or faith. Against this background, more purposeful qualitative research is needed to properly understand spiritual lived experiences within the SA/CSB paradigm. Understanding how SA/CSB discovery/disclosure affects an intimate relationship is essential since spiritual well-being and identity are fundamental to a healthy human being (Peerawong et al., 2019). This knowledge gap is addressed in this article.

While SA/CSB is not gender-specific, the majority of individuals in this cohort are known to be heterosexual men in relationships with women; men seem to be involved in these types of interaction four times more often than women (Ballester-Arnal et al., 2013; Cooper et al., 2000; Kishor et al., 2018). Consequently, the focus of this paper is on BT-linked spiritual impacts on women who are in committed relationships with men who have engaged in CSBs. It is crucial to acknowledge that the article’s focus on ‘heteronormative’ relationships does not negate the need for research on the potential impacts of SA/CSB on male partners of women who engage in such activities, homosexual or lesbian couples, or partners in open relationships.

Although spirituality highlights an individual’s search for meaning in life, religion centres on an organised body with rituals and practises based around a higher power or God (Arrey et al., 2016; Frankl, 1985). Furthermore, for some people, such as atheists or spiritual practitioners, spirituality and religion may go hand in hand (Arrey et al., 2016; Tanyi, 2002). Therefore, the current study deliberately elected to embrace an inclusive approach that encapsulates both spirituality and religion and uses the terms God/higher power in tandem. Consequently, to broaden the scope and maximise inclusivity, the current study deliberately recruited impacted female partners from diverse spiritual and non-spiritual backgrounds and did not discriminate between spiritually and religiously inclined persons.

Literature Review

As pornography has proliferated, it has been demonstrated to alter what is deemed to be ‘normal’ sexual conduct and, for some, has led to self-identification as addicts (Grubbs et al., 2019). Some have called harmful actions inspired by pornography ‘unwanted gifts that keep giving,’ raising concerns about whether these behaviours are always ‘optimal’ even though they may be ‘normal’ in the sense that they reflect common practice (Seyed Aghamiri & Luetz, 2023, p. 3; Seyed Aghamiri 2023a, 2023b). According to the largest audio-visual content provider, 84–94% of pornography is currently accessed on smartphones, with country-specific access rates varying (Pornhub, 2022). Furthermore, due to easy accessibility, pornography consumption has shifted the current sexual and gender scripts, which in turn affects the way that couples interact sexually and relationally (Burnay et al., 2022; Grubbs et al., 2020; Kohut et al., 2017; Wright, 2011). Pornography use, in general, and among Australian adults, has become commonplace (Hastings & Lucero Jones, 2023; Seyed Aghamiri et al., 2022a, 2022b) and represents the most common solitary activity that individuals with SA/CSB engage in (Bőthe et al., 2021; de Alarcón et al., 2019; Jha & Banerjee, 2022; Yunengsih et al., 2021). If one partner utilises pornography in a way that the other finds offensive, the stability of the relationship may be jeopardised, and moral standards surrounding sexuality, spirituality, and religion may be compromised (Leonhardt et al., 2018; Perry, 2017; Seyed Aghamiri & Luetz, 2021).

Although some studies have presented the linkages between CSB and spirituality or religiosity in individuals who engage in CSBs (Grubbs et al., 2019, 2020; Jennings et al., 2021a, 2021b) or in relation to impacted partner’s perceived support needs (Carnes & Lee, 2014; Manning & Watson, 2008), to date, no other studies have investigated the direct connections between SA/CSB and the effects on intimate partner spirituality and religiosity. Nevertheless, several studies have identified an urgent need for scholarly attention to the impacted partners’ overall experiences concerning their spiritual functioning (Seyed Aghamiri & Luetz, 2021; Vogeler et al., 2018; Weiss, 2021a, 2021b).

Diagnostic classifications of mental diseases have not included diagnostic categories for compulsive, addictive, impulsive, or out-of-control sexual behaviour for several decades. However, in the 11th edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) (Kraus et al., 2018; World Health Organization [WHO], 2019), Compulsive Sexual Behaviour Disorder (CSBD) has recently been added to the list of impulse control disorders. Because of the inability to regulate their sexual impulses and urges, which results in repeated and compulsive sexual conduct, people with SA/CSB experience significant impairment or suffering (Carnes, 2015, 2019; de Alarcón et al., 2019; Grubbs, et al., 2019; Weiss, 2019, 2021a, 2021b). A few examples of the behavioural components of SA/CSB/CSBD comprise compulsive engagement in non-partnered sexual activities, paid sexual services, masturbation, and other online and offline sexual interactions (Grubbs et al., 2020; Seyed Aghamiri & Luetz, 2021; de Alarcón et al., 2019; WHO, 2019).

One adverse impact of SA/CSB that can harm an intimate partner in multiple ways is betrayal trauma (BT), which may be brought on by SA/CSB discovery/disclosure (Seyed Aghamiri et al., 2022a, 2022b; Weiss, 2021a, 2021b; Williams, 2019). The term BT (Freyd, 1996) describes relational trauma and is associated with betrayals of trust (Birrell et al., 2017). More precisely, the degree of betrayal increases with the proximity and depth of one’s relationship with the offender (Freyd, 1994; Kahn & Freyd, 2008). Moreover, intense emotional distress experienced by an intimate partner who has been betrayed is comparable to that of a baby experiencing attachment injury while away from their mother (Johnson et al., 2001; Warach & Josephs, 2021). Similar to BT, attachment trauma is linked to existential anguish and suffering when traumatic interpersonal experiences occur that contradict a person’s inner conviction that someone else is a dependable and trustworthy source of support (Hazan & Shaver, 2017).

Furthermore, grief is frequently experienced by those affected by SA/CSB-related betrayals (Mays, 2023), which may intensify the spiritual detachment (D. Weiss, 2021a, 2021b). Intense feelings of rejection, abandonment, and rage, trauma symptoms, complex melancholy, humiliation, a profound sense of guilt or blame, and a ruminative need to rationalise or explain their identity and reality can all be experienced simultaneously by a grieving intimate partner (Seyed Aghamiri, 2023a, 2023b; Weiss, 2019; Zisook & Shear, 2009). Additionally, attachment injury caused by SA/CSB-linked BT contributes to a significant decline in confidence and self-worth, a lack of trust in self, God/higher power, and others, and a deep-seated dread of being abandoned in future intimate relationships (Charny & Parnass, 1995; Seyed Aghamiri, 2023a, 2023b; Weiss, 2019). Compared to other types of trauma, BT has a distinct effect on the brain, especially when the victim is dependent on the perpetrator (Courtois & Ford, 2014). Because of their physical, psychological, or spiritual dependency, BT victims frequently find it difficult to accept the reality of what has happened, endangering their entire sense of self (Freyd, 1994).

Empirical research indicates that a major contributing factor to the genesis of posttraumatic sequelae is betrayal (DePrince et al., 2012; Gómez et al., 2014; Kelley et al., 2012). According to Gómez et al. (2014), BT activates the fear centre, which can lead to complex trauma or PTSD and the symptoms that go along with it. Furthermore, complex trauma refers to interpersonal traumatic experiences that are premeditated, deliberate, and caused by other individuals (such as intimate partners) (Courtois & Ford, 2014). The literature describes complex trauma as relational and recurrent, inducing hypervigilance, agitation, anxiety, and a continual state of alertness (Courtois & Ford, 2014; Herman, 1992; Herman & van der Kolk, 2020). Thus, if BT is not addressed, it may proliferate and impose negative effects on people’s bodies, minds, and spirits as well as on society (Rohr, 2018; Seyed Aghamiri & Luetz, 2021).

To better understand how BT-linked SA/CSB may impinge on intimate relationships, a better comprehension of human spirituality and religiosity is necessary. Around 27% of people identify as exclusively spiritual, although many people may identify as both religious and spiritual (Lipka & Gecewicz, 2017), indicating that these conceptions are associated but distinct. There may also be new interactions between these and other constructs, including in relation to traditional/indigenous forms of spirituality (Luetz, 2024; Luetz & Nunn, 2023) and how to effectively support spiritual growth (Hukkinen et al., 2023).

The Latin term spiritus, which means ‘breath of life’, is the source of the word ‘spirituality,’ which is commonly employed in the literature to describe various facets of human existence, including aspects pertaining to the mind, body, emotions, and soul (Santos & Michaels, 2022; Nunn & Luetz, 2021). Therefore, spirituality encompasses the psychological realm as well as the hidden human desires, meanings, and meaning-making processes, and it both inhabits and informs the domain of the non-rational (Holloway & Jupp, 2020; Santos & Michaels, 2022; Maslow, 1981; Frankl, 1985). Interpretations of spirituality offered by academics frequently reference Elkins et al. (1988) and discuss the links between spirituality and ultimate concerns: ‘a way of being and experiencing that comes about through an awareness of a transcendent dimension and that is characterised by certain identifiable values regarding self, others, nature, life, and whatever one considers to be the Ultimate’ (p. 10). Significantly, Knight (2006) has posited that humans, ‘at their deepest level are motivated by metaphysical beliefs’ (p. 19), and there is support in the literature for the idea that spirituality may be conceived or even leveraged as a social resource (Hulme, 2021). While religion focuses on an organised body with rituals and practises centred around a higher power or God, spirituality emphasises an individual’s search for meaning in life (Frankl, 1985). While some people perceive spirituality and religion to go hand in hand, others note differences, including in relation to the views of atheists or spiritual practitioners (Arrey et al., 2016; Tanyi, 2002). In summary, spirituality and religion are circumscribed by a broad and fluid definitional base and cannot be limited to a single, narrow, and/or universal definition (Hills et al., 2016; Luetz & Nunn, 2023; Rocha & Pinheiro, 2020).

As noted previously, to date, there are no other studies that have qualitatively investigated the spiritual impacts of CSBs on intimate partners following the discovery/disclosure of such conduct. Nevertheless, some researchers, e.g., Carnes and Lee (2014), Taylor (2015), and Weiss (2019), have noted peripherally that BT brought on by SA/CSB can have severe ramifications on the impacted partner, which may include spiritual or religious crises. Furthermore, Carnes and Lee (2014) observed that partners of individuals with SA/CSB recurrently experienced feelings of rejection and abandonment from God/higher power, as well as anger and a sense of disconnection. Additionally, Carnes and Lee (2014) found that the impacted partners had stopped participating in religious or spiritual practices as a result of feeling ashamed of their partner’s CSBs. Although sexuality and sex are common aspects of human experience and are not inherently religious (Tomaszewska & Krahé, 2016), they may nevertheless engender spiritual implications for both religious and nonreligious individuals due to variable notions and expressions of how humans perceive their own essence and conceive of meaning-making (Peerawong et al., 2019; Weiss, 2019).

Several studies have revealed that traumatic experiences might significantly contribute to existential and spiritual crises (Muehlhausen, 2021; Park, 2020; Webb, 2004). A spiritual crisis, also referred to in the literature as a ‘spiritual emergency’, is a state induced by trauma in which an individual experiences profound shifts in their meaning-making system, affecting areas of their identity, purpose, values, attitudes, and goals (Muehlhausen, 2021; Park, 2020). Additionally, an impacted partner’s spiritual crisis may have been precipitated by the interconnected ramifications of BT and infidelity, wherefore it is essential to understand trauma in relation to SA/CSB-induced infidelity. Research has shown that infidelity in intimate relationships, even when limited to compulsive pornography consumption (a type of SA/CSB), can be just as harmful as physical betrayal (Schneider et al., 2012). Relatedly, infidelity is known as the most serious betrayal that may happen in a romantic relationship and the one that poses the most damage to the relationship’s stability (Beltrán-Morillas et al., 2015; Dillow et al., 2011). Given the high standards of commitment and devotion that many people ascribe to their relationships, infidelity is commonly regarded as an act of ultimate betrayal (Hall, 2016; Fincham & May, 2017; Watkins & Boon, 2015). This sense may be heightened by the considerable time and energy necessary to maintain such deceptive and concealed behaviours, sometimes over long periods of time (Dillow et al., 2011; Fife et al., 2013). Furthermore, unwary partners do not anticipate their mates to commit unthinkable betrayals like infidelity because of their shared relationship commitments, e.g., time, money, experiences, children, etc. (Dillow et al., 2011; Watkins & Boon, 2015). While intimate relationships can engender some of the most fulfilling experiences in life, they can also lead to some of the most painful and disappointing experiences as well (McNulty, 2011). Many definitions have been proposed to explain the concept of infidelity (Thompson & O’Sullivan, 2016b; Thompson et al., 2017). One common definition of infidelity entails the notion of a violation of the mutual commitment to a relational contract or boundary requiring relational exclusivity and may manifest as brief or prolonged sexual, emotional, or other encounters with someone other than the primary partner (Dillow et al., 2011; Fife et al., 2013). However, given the variety of extradyadic behaviours that might be considered deceitful, not all types of infidelity are likely to affect people in the same way (Thompson & O’Sullivan, 2016a). Various categories of online and offline extradyadic behaviours are associated with BT-linked infidelity. These consist of (a) sexual behaviours (i.e., oral sex, vaginal, or anal penetration); (b) technological/online behaviours (i.e., any sexual interactions via digital devices); (c) emotional/affectionate behaviours (i.e., sharing secrets with someone besides the partner); and (d) solitary actions (e.g., masturbation) (Carnes, 2015; Dillow et al., 2011; Fife et al., 2013; Futrell, 2021; Seyed Aghamiri, 2023a, 2023b; Weiss, 2021a, 2021b).

Significantly, the most serious and least forgettable or forgivable type of betrayal is considered to be sexual infidelity (Beltrán-Morillas et al., 2015; Pettijohn & Ndoni, 2013). Notwithstanding, the introduction of new technology has revolutionized how people interact and communicate sexually (e.g., sexting), which has had a decisive effect on romantic relationships and given rise to new forms of sexual infidelity (Clayton, 2014). Consequently, since these extradyadic behaviours are easier to participate in, conceal, and deny, there are far more opportunities to engage in them outside of the primary partnership (Vossler & Moller, 2019). As such, the partner who is injured by technological betrayal may have intense negative emotions (such as indignation, fear, embarrassment, or guilt), just like in the case of physical sexual infidelity (Schneider et al., 2012; Zitzman & Butler, 2009). In addition, there is a high incidence of relationship dissolution or divorce, loss of relational trust, experiences of grief, and compromised relationship quality (Schneider et al., 2012; Valenzuela et al., 2014).

In summary, the scarce available literature on this topic points to fertile opportunities for future research. No other peer-reviewed study has expressly permitted women to reveal the true essence of their lived experiences and articulate meaningful spiritual perspectives following the discovery/disclosure of their partner’s SA/CSB. Considering the importance of an individual’s well-being and functioning, discussing SA/CSB in tandem with spirituality/religiosity has been described as a promising aspiration if such thematization can be meaningfully ‘mainstreamed and normalised—rather than moralised—for the greater good of both sufferers and society’ (Seyed Aghamiri & Luetz, 2021, p. 443). Specialists, professional caregivers, and faith-based organisations stand to benefit from more in-depth knowledge about women’s spiritual lived experiences and perspectives in this area. Applying an in-depth qualitative analytical approach can help to identify prospects for healing and recovery.

Methodology

To investigate the spiritual ramifications associated with the discovery/disclosure of SA/CSBs in intimate relationships, this section addresses the methodological approaches to data collection and analysis from counsellors (supplementary participants) and intimate female partners (primary participants). To advance the evolving field of study, this research design was carefully chosen. Qualitative research methods analyse events in a specific context to generate new theory, as opposed to quantitative research methods, which describe variables and test hypotheses (Creswell, 2015; Peoples, 2020). Considering this, by generating hypotheses, the current work adds to the corpus of theory generation research (Chen & Luetz, 2020).

Despite some limited research suggesting that SA/CSB has negative effects on intimate partners, as mentioned above, there is a large knowledge gap in the peer-reviewed academic literature regarding systematic qualitative studies that illustrate the spiritual lived experiences of BT-affected female partners (Bergner & Bridges, 2002; Schneider, 2000a; Schneider et al., 1998; Schneider et al., 2012; Williams, 2019; Zitzman & Butler, 2009). In light of the spiritual effects of BT, the present qualitative design was developed and used to give voice to, better understand, and capture the essence of this understudied population. Extensive investigation into the actual experiences of this demographic could reveal contextual or cultural commonalities or distinctions among the impacted women (Milrad, 1999; Schneider, 2000; Steffens & Rennie, 2006; Williams, 2019; Zitzman & Butler, 2009).

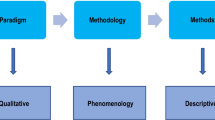

Given that a qualitative approach offers a comprehensive understanding of the interactions between spirituality and biopsychosocial phenomena, it may, therefore, result in improved healthcare delivery (Boyle, 1991; Rew & Wong, 2006; Seyed Aghamiri & Luetz, 2021). Lastly, such a focus can help direct the development of suitable social policies more effectively (D. Weiss, 2021a, 2021b). In pursuit of this goal, the study purposefully used a phenomenological framework situated inside a qualitative research paradigm. It is possible to give numerous fresh perspectives and ideas regarding the spiritual experiences of the impacted women, and a phenomenological method can help explore all the diverse shared experiences. To this end, the study implemented the specific descriptive phenomenology research method documented by Seyed Aghamiri et al. (2024).

The following research question guided the investigation: What are the lived experiences of women following the discovery/disclosure of their male partner’s SA/CSBs?

The most suitable methodological approach for this study was a qualitative framework with an emphasis on phenomenological understandings because the goal was to explore and characterise lived human experiences. Descriptive phenomenological techniques were thus employed to collect and process the data to investigate the study topic. Within the qualitative paradigm, a phenomenological study examines all of the experiences that study participants wish to share, offering different viewpoints, ideas, and fresh understandings (Creswell, 2015; Giorgi et al., 2017; Peoples, 2020). Husserl’s phenomenological approach is essentially philosophical and epistemic, exposing knowledge that correlates with human experience (Husserl, 1970; Neubauer et al., 2019). As a result, descriptive phenomenology demands that lived experience be prioritised in addition to a thorough and in-depth explanation of the universal core of participants’ experiences and meaning-making. By enabling women impacted by their male partner’s SA/CSB to express their lived experiences via their narratives, this approach also honours the lived experiences and well-being of these women (Blycker, 2023). Furthermore, the research aimed to clarify the subtleties and intricacies of personal encounters and acquire a comprehensive understanding of pertinent interpretation procedures (Willig, 2013). Crucially, because this study concentrated on the significance and calibre of experiences, qualitative approaches were the most appropriate (Denzin & Lincoln, 2013).

Data Collection and Research Ethics Approval

The procedure for gathering data included securing approval from the research ethics committee, finding and choosing participants, gathering demographic data, guaranteeing anonymity, gathering informed consent forms, and carrying out in-depth semi-structured interviews. The study was approved by the Alphacrucis Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. See Section Ethics Approval and Institutional Review Board Statement below for pertinent details.

Selection and Recruitment of Participants

The following information was gathered from a diverse group of primary participants: age, ethnicity, length of relationship with the male partner, education, income level, occupation, religious or spiritual background, and number and age of children. To prevent biased selection, the Sexual Addiction Screening Test (SAST) developed by Carnes (1991, 2000) served as the tool for identifying the appropriate participants. To be eligible for participation, a minimum of three SAST criteria had to be satisfied continuously for a full year.

The study’s objective was to examine female partners through the lens of social construction. Therefore, no medical diagnostic instruments were employed to determine eligible study subjects. Twelve Australian female partners (FP) between the ages of 21 and 63 (the primary group) and fifteen counsellor participants (supplementary group) were recruited using non-random sampling. The affected female participants had to be (or have been) in a committed, exclusive relationship (with a male partner) for a minimum of 12 months to be eligible for recruiting. While thorough phenomenology research necessitates an adequately small sample size (Creswell, 2015), this qualitative study included a manageable number of participants (n = 27) who were specifically chosen to enable in-depth analysis and comprehension of the phenomenon of interest (Patton, 2002).

In-person interviews with each of the primary participants were conducted at a private counselling facility in Brisbane, Queensland (Australia). A few female participants were also enlisted through 12-step programs run by SAA (Sex Addicts Anonymous) and SA (Sexaholics Anonymous), where their male partners attended meetings to receive peer support for their SA/CSB. Moreover, snowball sampling was used to find additional female participants, which is suitable for investigations looking into covert research populations (Naderifar et al., 2017). The counsellors represented a broad spectrum of demographic groups, including Australian citizens who were employed as professional counsellors, psychologists, physicians, or pastors with counselling qualifications. By including this additional research participant group, methodological rigour was improved through triangulation (Creswell, 2015; Fusch et al., 2018).

Instruments: In-Depth Semi-Structured Interviews

The participants were free to provide as much or as little information as they wished during the semi-structured interview process.

Interview Questions

The data collection instrument comprised thirteen open-ended questions inviting the female partners (primary participants) to share their experiences after learning about their male partner’s SA/CSBs. Sample questions from the instrument include:

-

How would you describe your emotional, physical, or spiritual life experiences following the discovery/disclosure of your partner’s CSBs?

-

What were your needs during and following the discovery/disclosure, and how were those met?

-

What is your outlook on life now?

In addition, the professional counsellors (supplementary participants) were asked three open-ended questions to share their professional observations of working with this demographic. An example includes:

-

What impacts, if any, have you observed on the female partners’ well-being as a result of the discovery/disclosure of their mates’ CSBs?

Additionally, prior to completing the interviews, a pre-test of all interview questions was conducted with a number of academics, pastors, counsellors, and couples who had experienced SA/CSB. Because of this, the questions had to be revised and changed multiple times before the instrument was finalised.

Data were gathered and analysed from 2021 to 2023. This involved using an analytical strategy that supported coding and theme development processes and comprised manual coding and multiple rounds of computer coding in NVivo 12 (QSR International, 2021). From the time of the first interviews to the end of the data collection procedure, thematic data analysis was carried out. Emergent patterns and themes were investigated in the interviews to distil the essence of the experiences of the female partners. To better understand the data, this approach required field notes and reflection journaling. Husserl’s (1970) philosophical prerequisites and Sundler et al.’s (2019) methodological procedures were used to analyse the data using an open-minded reading approach to comprehend the data. When transcripts were read aloud numerous times, ‘with an open attitude,’ major themes began to emerge from the text (Seidman, 2006, p. 117). Next, the audio recordings were listened to while simultaneously the transcripts were read multiple times to identify themes and meanings. The participant’s vocal tone was now noted, which helped interpret some of the text’s meanings. Relevant statements were also examined for meanings. They were categorised, organised, and coded into different groupings because pertinent primary meanings indicated a detailed description. The method of coding involved recognising unique characteristics and annotations that were thought to be helpful in addressing the study topic (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). Lastly, categorising topics into a meaningful unity was the task of data analysis. This was achieved by looking for prominent expressions in the participant descriptions. It was crucial to let meanings evolve organically rather than forcing them to be constructed quickly.

Results

Most of the women reported that the pain and suffering that they endured led to their initial alienation from God/higher power. This finding holds significance—although the women had different backgrounds in terms of demographics, they shared comparable spiritual lived experiences. All female participants said that the pain and grief of their traumatic experiences affected aspects of their spirituality (Fig. 1). A total of 83% expressed experiencing some kind of spiritual crisis, doubting God’s justice, and feeling initially let down. As such, these female partners described a sense of detachment from their God/higher power initially. Nevertheless, most women only briefly experienced spiritual coldness (50%), a small percentage of the women discovered completely new beliefs or spiritualities (25%), and some women endured ongoing spiritual apathy (25%).

Most women who first experienced drifting away from God did so out of anger and a sense of betrayal. They had lost faith in God, other people, the male partner, and themselves. The female partners recurrently affirmed that they felt betrayed and deceived by God because God had allowed the offence to transpire. They seemed to convey a sense of injustice and ‘being angry towards God’ (FP 08). They did not understand why this would happen to women who had been strong, dedicated members of their faith/church communities. The following quotation exemplifies this sentiment:

I’ve always been involved in church, from the day I was born. My family was pastors and missionaries and all that. The church was just a way of life for us. But it was too volatile for me to lose focus from the incredibly traumatic world I shared with my partner for even one second to ask God for help. (FP 07)

Another woman related a similar ‘why’ question and indicated:

A lot of times, I vented out: why? Why did this happen? Why did you let it happen? Why did I have to go through so much pain as a person who was raised in a very strong spiritual house and Christian family? I know I’m not perfect, but I felt I was always loyal to Him [God], and I never went out of His pathway, doing rebellious teenage things or dangerous things. I question why my loyalty to Him was not reciprocated back? And maybe, like Job with the Bible story, being a faithful servant, everything was suddenly taken from him. Why has that happened to me? (FP 13)

Several participants reported that God seemed to have abandoned them. One Christian woman said:

I used to always have faith in God, and I used to pray and be grateful. After the discovery, I lost my faith a bit because I thought, ‘This is not fair that it’s happening to me.’ I had lost my connection with my higher power, with my God. I felt this was so unfair: ‘Why is this happening to me?’ (FP 01)

A female participant who was raised as a Muslim shared how she felt moving away from her faith as a result of her partner’s conduct, saying, ‘Coming from a very religious upbringing, I thought maybe it would push me closer to God … but then it was kind of like ‘Not this, this isn’t going to help me’, and now I just don’t know where I belong’ (FP 02). Other Christian women shared their spiritual struggles, with one saying, ‘Initially, I felt kind of more disconnected from God and just more sad’ (FP 05). Another woman who had been an active member of her church for many years reported how she drifted away from her faith-based community and God following her discovery of her husband’s CSBs. She elucidated:

I don’t believe at all and have no faith. I think having a God with a plan and all that is hogwash now. I think now, if there really was a God, a loving God, why would he not have let me find out earlier? Why? There was plenty of opportunities to let me find out. I think he is either a very cruel and vindictive or evil God because no good God would ever do that to another being. I wouldn’t even do this to my worst enemy. (FP 11)

Several women expressed their belief that God ‘isn’t going to help me’ (FP 02), and therefore ‘He must hate me’ (FP 03), and wondered why their faithfulness was ‘not reciprocated’ (FP 13), prompting them to ‘move away from God’ (FP 04). Additionally, many women of faith described how their faith-based communities had been unhelpful or failed to support them effectively. Consequently, they felt more spiritually distanced and disconnected. There was also the perceived expectation of quick forgiveness without concern for the women’s trauma or grief processing in some cases. One Christian woman, for example, revealed:

I couldn’t talk to my church community due to stigma and judgment … I was physically and emotionally unstable, and those who were supposed to care for me didn’t do a good job of keeping me safe … I would have healed faster if I had my faith-based community around me. (FP 09)

One counsellor/educator shared his observations concerning what would be harmful to the affected women of faith and indicated:

I think many church leaders would not want the dynamic. ‘Out of sight, out of mind’ — just tell me he or she is doing all right. There’s no systemic kind of family dynamics that get much of the attention. So much of it is on the addiction itself, and if I think across the past decade or two, it’s kind of a big gap, and more needs to be done. (C 02)

One woman expressed her dissatisfaction with her pastor, who asked her to ‘read the Bible and be forgiving’ (FP 09). Further, one Christian woman wondered, ‘Does this make me a bad Christian, because I’m struggling to forgive him? Because every time I look at him or every time he wants sex, it reminds me again, and I remember again that I haven’t forgiven him’ (FP 08).

Furthermore, the overwhelming majority of counsellors (including pastors, C 11, C 14 and C 15) reported observations of some sort of bitterness or distancing from God. These responses mirrored what the female partners had shared. They stated that ‘a lot of women are feeling spiritually betrayed, that God has let them down’ (C 04) and ‘having found out they’ve been deceived in one area, they might spiritually wonder if they had been deceived in other areas’ (C 06). One counsellor, who was also a medical practitioner, added:

The spiritual impacts would be similar to PTSD. It would be traumatising, and sometimes, there may be a physical and emotional resolution, but their spirit is still in shock. So, there are leftover effects of separation, rejection, withdrawal, [and] disconnection from God as well as other people. (C 07)

Another counsellor noted that ‘Some women have those questions about why does God let this happen. Or some who don’t have that connected relationship with God may actually decide that He can’t be trusted either, because they have this male patriarchal idea of God’ (C 10). According to one pastor/counsellor’s observation, initially, ‘everyone goes through the confusion and gets angry with God’ (C 11). Moreover, ‘a lot of partners lose their faith because they can’t understand why God would do something like this or let something like this happen’ (C 13). As a result, according to another counsellor/pastor, the female partners could experience some form of ‘bitterness towards God, or a judgment towards God, or even blame’ (C 14).

After the initial estrangement, a few women (25%) reported discovering new spiritual beliefs. Some described their experiences as a movement towards God or a new faith/spirituality. For example, one of the female partners characterised her spiritual journey as follows:

When I grew up, I was in a fundamentalist cult. I left that religion of rules and regulations and was an atheist for a long time, and then I became agnostic, if you like. But what has come from this, because my partner is into Buddhism, I’ve become much more interested in that kind of thinking. I’m a humanist, I guess, in that way. I still believe in a higher power (FP 3).

Another participant, who grew up in a Muslim family but was a ‘non-believer/atheist’ at the time of the discovery, described how the experiences moved her towards a completely new faith, saying:

A few months into our recovery, I found peace at church and felt the need to reconnect to God. He was the only one for me, as I couldn’t reach out to anyone else. God became my coping mechanism. I could talk to Him, getting angry and ask Him: ‘Why me?’ … Faith gave me hope and a purpose and saved me from self-harm and other dangerous, unhealthy thoughts. (FP 09)

One woman described the path she and her partner had taken towards a relationship with God, saying: ‘I was never connected to God, really, but this journey has really connected us to God, which is good because we both have a higher power now’ (FP 12).

Being among an accepting and safe community amid their pain meant some women could rely on and ‘trust in God’s providence’ (FP 06) and experience a ‘blossoming’ (FP 07) of their faith/spirituality once more. Finding a community that supported and embraced them during their grief eventually offered some of them ‘hope and purpose’ (FP 09), a safe space they could ‘run to with their pain, cry, lament, and prayers’ (C 15), and the ability to trust and feel ‘connected to God again’ (FP 05). Aligned with what a few of the female partners indicated concerning closeness to God in the aftermath of their experiences, one of the counsellors said:

Sometimes the relationship with God and spirituality have been vitally important because it has been like an anchor for a partner who is spiralling, not knowing how to deal with what’s going on and not knowing how to find their way. So it has been a journey towards God. (C 11).

Other counsellors acknowledged this and stated, ‘For the female partners, sometimes they become stronger, become independent women and rely on God more’ (C 12). One counsellor/pastor said, ‘The ones that have worked through these sorts of issues with their partners have gotten closer to God’ (C 14). Furthermore, ‘Some people in a time of crisis fall into God and say they need Him more than ever, so their relationship becomes incredibly fruitful, life-giving’ (C 15). Such new directions towards God or a higher power reflected how some women experienced their faith and its meaning during their trials and tribulations. In summary, although most affected women initially moved away from God/higher power, a few of them eventually discovered new forms of spirituality.

Discussion

This study found that after learning about SA/CSB in their intimate relationships, most of the female participants—including the atheists—expressed rage at God. What kind of God could let this happen and then abandon them was a key question raised. Some women then went through a period of total spiritual alienation and detachment. They did not see anything worthy of reverence or faith. Most women felt that they had been let down by their communities, which they perceived as extensions and manifestations of God/higher power. This perception prevailed because most women had not received appropriate validation or support. Spiritual crises of moving away from God/higher power evoked questions such as ‘Where is God?’ and are consistent with what Carnes and Lee (2014) have touched on as adverse spiritual effects or spiritual trauma in betrayed partners. In the current study, 83% admitted to initially feeling angry at God and questioning God’s justice—even those who identified as atheist (FP 09), agnostic (FP 02) or who simply stated they did ‘not believe in God’ (FP 03). This is noteworthy in light of Rohr’s (2003) reflections that our relationship with God/higher power reflects our other relationships:

How we relate to one thing is probably how we relate to everything. How we relate sexually is probably a good teacher and indicator of how we relate to God (and how we relate to God is probably a good indicator of how we will relate to everything else). (p. 136)

Furthermore, some felt pressured by their clergy or faith-based group to extend forgiveness too quickly. For many of the women who were affected, the first act of betrayal by their male partner followed a second act of betrayal by God, their religious community, clergy, or other spiritual leaders. This ultimately resulted in a BT-linked spiritual crisis. This finding aligns with what Taylor (2015) noted: more than 63% of the 100 women who responded to her survey reported they had gone through a significant spiritual crisis at some point in the wake of learning about their partner’s SA/CSB. Furthermore, the impacted women believed that the church, their spiritual community, and/or God had abandoned them. One intriguing finding of the present study was that women who identified as agnostics or atheists also experienced feelings of anger or mistrust about God’s justice. Empirical investigations suggest that although a large number of people deny the existence of God, they may also be the ones who are most enraged with him (Exline et al., 2011). People who perceive God as the cause of extreme suffering or harm frequently sense anger at God, which is a typical spiritual conflict (Exline et al., 2013; Weber et al., 2022). The Anglican lay theologian C.S. Lewis (1898–1963) is quoted by Nicholi (2002) as having bluntly admitted,

‘I was at that time living like many atheists; in a whirl of contradictions. I maintained that God did not exist. I was also very angry with God for not existing. I was equally angry with him for creating a world’ (p. 51).

Exline et al. (2011) assert that the mental and emotional processes involved in a relationship with God are similar to those involved in relationships with other individuals. Because of this, a relationship with God/higher power can evoke both positive and negative feelings, just like interactions with other people (Beck & Haugen, 2012). According to Risner (2023), when our dreams lie broken all around us, and the God we believed loved us lets them break, it might be difficult to comprehend what it is to be loved. In other words, earthly vertical relationships with God/higher power may translate into earthly horizontal interpersonal domains.

Furthermore, there seemed to be a connection between spiritual crisis and BT-induced grief (Agrimson & Taft, 2009; Burke et al., 2019). It has been scientifically established that grief is associated with the breakdown or erosion of the griever’s sense of security with God and/or their faith community (Burke et al., 2019; Neimeyer et al., 2021). Relatedly, other findings from the current study suggest that some female partners found their pastors or faith communities judgmental, insensitive, unaware of CSB, and/or driven to demand hasty forgiveness, which exacerbated the women’s grief. Consequently, this aggravated the female partners’ sense of detachment from God/higher power. Furthermore, the findings of this study concerning moving away from God and spirituality reaffirm similar findings of Carnes and Lee (2014). Similarly, Manning and Watson (2008) noted a lack of support from faith communities and that approximately one-third of female partners of men with SA/CSB viewed clergy as unhelpful. Furthermore, Weiss (2019) stated that some pastors are unhelpful because they lack essential specific training in counselling to support partners with BT and that women are routinely urged to forgive and forget (King, 2003; Laaser & Adams, 2019).

In this study, the betrayed women did not initially receive validation or assistance from their faith-based communities; instead, they felt pressured by the church leaders to ‘read the Bible and be forgiving’ (FP 09). This also corroborates the findings of Laaser and Adams (2019), who discovered that 34% of their study participants regarded admonitions of hasty forgiveness as least beneficial for partners. Although, in general, forgiving is associated with positive physical and mental health outcomes (Lichtenfeld et al., 2019), it is worth remembering that in the literature, infidelity, cheating, and lying are reported as the least forgivable behaviours (Beltrán-Morillas et al., 2019; Grøntvedt et al., 2020; Thompson et al., 2020), wherefore any impositions of hasty forgiveness seem ill-advised (Laaser et al., 2019). There appears to be a universal consensus that forgiveness is a multifaceted phenomenon involving cognitive, affective, behavioural, motivational, decisional, and interpersonal aspects (Kelly, 2018; Lichtenfeld et al., 2015, 2019). However, researchers also agree that forgiveness is not the same as disregarding (meaning that the offence is minimised), excusing (suggesting that the offence is justified), forgetting (indicating that the offence is not consciously accessible), or reconciling (pointing to the restoration of the relationship) (Freedman & Zarifkar, 2016; Lichtenfeld et al., 2019; McCullough et al., 2009). Moreover, forgiveness is not a one-time event and does not necessarily mean pardoning the offence or the offender (Lichtenfeld et al., 2015). Furthermore, as postulated by Goertzen (2003), forgiveness is not ‘a refusal to acknowledge the offence’ (p. 4). According to the shared sentiments of the affected women in this study, the reality of the transgression and the legitimacy of the resulting grief needed to be acknowledged and validated for genuine forgiveness. This process appears to take time and seemingly depends on the perceived severity of the wounds. Therefore, it is counterproductive to minimise the depth of the hurt by rushing to unearth and process all the underlying layers. As seen in the results of this study, the road to even considering forgiveness for most betrayed women was paved with perceptions of trauma and grief. In the wake of discovery/disclosure, for most impacted women, remaining in their intimate relationship or considering forgiveness meant going against their own values and convictions. They stated emphatically that they would never choose to be with someone deceitful. For betrayed partners, forgiveness means sacrificing the previously envisioned version of what the future would hold and letting go of the terrible realities of the past in the aftermath of the SA/CSB revelation.

The current study’s findings suggest that churches or clergy who pushed for hasty forgiveness either pretended that the offence had not happened or minimised it while the reminders of the betrayal and subsequent trauma responses lingered. Rushed forgiveness may have prepared the soil for bitter seeds to grow in some women’s souls, thus contributing to perceptions of transient or permanent disconnection from God/higher power. In the aftermath of experiencing BT, the female participants seeking support appeared to be deprived of the necessary accountability, boundaries, and safety. The study’s results are consistent with earlier research, which suggests that the gift of forgiveness—as well as its positive aspects—are lost when safety concerns, intrusive thoughts, unexpected triggers, unpleasant memories, and lingering mental images—all of which were common among the female partners—are disregarded, while premature forgiveness is enforced (Chi et al., 2019; Grøntvedt et al., 2020).

Notably, all major faith or spiritual communities seemingly tend to favour men and their rights over women, while women dominate the ranks of the faithful and devoted around the world (Candler, 2022; Hackett et al., 2019; Nesbitt, 2014). Women, for example, account for over 60% of church attendance (Powel, 2017). Moreover, even though women are typically constrained by greater caring responsibilities than men, women volunteer more in their faith communities (Krause, 2015; Southby et al., 2019). Therefore, it would be logical to suppose that when this group faces calamities, there would be expressions of prompt respect and demonstrations of effective support throughout traumatic experiences rather than dismissal coupled with requests for hasty forgiveness and the possibility of re-traumatisation. In this context, demands for hurried forgiveness or being shamed for not granting it suggest a prescriptive approach and an arbitrary timeframe for moving on after betrayal, thus neglecting the fact that everyone’s time frame is unique and different. According to Woodiwiss (2014),

Trauma permanently changes us. This is the big, scary truth about trauma: there is no such thing as ‘getting over it.’ The five stages of grief model marks universal stages in learning to accept loss, but the reality is in fact much bigger: a major life disruption leaves a new normal in its wake. There is no ‘back to the old me.’ You are different now, full stop (p. 1).

Overall, the findings of the current study support previous research and demonstrate that forgiveness is a complex and costly process that cannot be rushed or prematurely granted and that it is neither a cure-all nor an evil crime when withheld (Beltrán-Morillas et al., 2019; Chi et al., 2019; Freedman & Zarifkar, 2016; Goertzen, 2003; Grøntvedt et al., 2020; Lichtenfeld et al., 2015; McCullough et al., 2009; Thompson et al., 2020).

In the aftermath of BT, a few of the women gravitated towards entirely new faiths or spiritualities as a way to find hope and effectively cope with their new realities. This finding is a significant contribution of the current study and confirms a lingering gap in the literature in this field of research. Although moving towards a new faith/spirituality has been investigated in individuals who engage in CSB (Fernandez et al., 2021; Giordano & Cecil, 2014; Jennings et al., 2021a, 2021b), such transition has not yet been specifically examined among intimate female partners following discovery/disclosure.

Faith/spirituality seemed to offer the affected women a coping strategy and a meaningful and deep narrative for some of their experiences. In addition, it provided positive coping, which was particularly beneficial for betrayed women who had no control over their partner’s secretive behaviours and their consequences. At times, the affected women could also use their beliefs and practices to make sense of perplexing and painful situations. Similarly, faith/spirituality appeared to help some women nurture feelings of hope in the face of uncertainty, which helped them to cope and boosted their mental health amid profound grief and BT experiences. These findings resonate with some parts of the literature that suggest that a person’s relationship to God or a higher power provides their life with meaning and purpose (Starnino, 2016), gives a sense of control in a changeable world (Bożek et al., 2020; Kay et al., 2008), provides a foundation for self-improvement (Sedikides & Gebauer, 2009; Villani et al., 2019), has positive effects on health attitudes and behaviours (Rew & Wong, 2006), and offers meaningful strategies for coping (Ozcan et al., 2021; Tedeschi et al., 2018).

In summary, a person creates their spiritual identity in relation to their social, emotional, intellectual, and sexual identities (Poll & Smith, 2003a, 2003b). However, social guilt, stigma, and a lack of professional and spiritual support seem to make it difficult for individuals and intimate partners to find assistance, which can undermine spiritual connectedness (Seyed Aghamiri & Luetz, 2021). Given the significant role that spiritual groups may play in fostering and sustaining individual and community connectedness and nurturing a stronger relationship with God or spirituality, it appears surprising that there is so little deliberate attention paid and appreciation offered to the impacted partners (Seyed Aghamiri & Luetz, 2021). This study discovered that, concerning the complex spiritual influences on an intimate partner’s health and functioning, this field has not received sufficient scholarly attention. However, if explored and better understood, it holds the potential to be concretely beneficial to both affected individuals, society and faith-based communities.

Conclusion

Husserl’s (1970) lifeworld served as a theoretical lens through which the current study perceived phenomena represented by the women’s spiritual lived experiences. The female partners described their spiritual experiences as complex and multifaceted and articulated narratives that offered new insights into the phenomena. Figure 2 provides an overview of some of the women’s spiritual lived experiences. This study underscores the lack of research on SA/CSB and its various consequences, with a specific focus on the spiritual repercussions experienced by female partners whose trust has been breached due to their partner’s hidden CSBs.

Based on the findings, partners often deal not only with that initial discovery but also with a continuous series of discoveries that result in a variety of trauma responses, including anguish and anger directed towards God/higher power as the perceived co-conspirator in the deception. Furthermore, the betrayed partner’s narratives frequently conveyed experiences of stigma and exclusion from faith-based communities, being pushed to grant hasty forgiveness, and/or being forced into isolation. In essence, the intimate partners are simultaneously addressing the initial trauma and managing the ongoing fear of experiencing spiritual gaslightingFootnote 1 through their faith-based communities. By spiritual gaslighting, the authors refer to a form of psycho-spiritual abuse in which spiritual leaders or institutions control and manipulate individuals into doubting their own judgement, experiences, or even sanity. The significance of a person’s spiritual well-being and functioning intersects with other aspects of their lived experiences and vice versa (Siemens, 2015). As such, the psychological and spiritual requirements of intimate partners—such as being validated, acknowledged, and freed from shame—are seemingly under-recognised and frequently dismissed by faith-based communities and healthcare providers.

Following the discovery/disclosure of their partner’s SA/CSB, most women did not receive adequate information, experience validation, or encounter a secure environment within their faith communities. Additionally, some experienced demands for hasty forgiveness. According to the shared narratives reported by the affected women, providing a safe community without spiritual gaslighting or pushing for premature forgiveness is imperative for healing and spiritual preservation. Faith communities of all persuasions have a responsibility to educate themselves concerning this destructive social phenomenon; doing so would better align with their calling to support people who are suffering and marginalised. This form of compassionate support needs to be extended both to the impacted partners and to the individuals themselves who struggle with this disorder. Regrettably, social taboos and stigma surrounding SA/CSB shroud the subject in shame and ignorance. This study found that disregarding the women’s experiences and mandating a narrow biblical interpretation concerning relational obligations is not conducive to facilitating healing. Moreover, some faith-based communities may benefit from re-examining their hermeneutics to prevent passages of scripture from being taken out of context and misused to invalidate or discount the betrayed partners, or to pressure them to forgive.

There was also a sense that some women of faith hinted at an idealised religious understanding of marriage (e.g., one has to make the marriage last at any cost; sexual intimacy is the highest form of union, etc.). One might wonder whether questionable religious interpretations of marriage might be part of the problem here, especially in generating so much shame, and in making women so reluctant to leave their marriage. Some religious communities seemingly place very little emphasis on the benefits of divorce as a remedy, thus raising these areas as fertile topics for future research.

The findings of this study have generated new knowledge that has implications for individuals, professionals, healthcare delivery, faith-based communities, future research, and education. The implications of this study may affect not only the impacted women but also churches, pastors, and other members of spiritual and religious communities. Furthermore, specific faith-based organisations might benefit from re-evaluating their approaches and procedures surrounding their support delivery to prevent re-traumatising affected women. It is critical for religious groups to offer affected women a place of refuge and solace where there is no condemnation or shame placed on them. Instead, the impacted women should receive validation for their experiences and be either given practical support or directed towards qualified specialised healthcare practitioners.

The current study is subject to some limitations of scope and points to future research opportunities. (1) Data were only gathered from Australian women based in the greater Brisbane area and hence did not investigate alternative sociolinguistic or geodemographic contexts; (2) data were sourced only from respondents in heterosexual relationships; (3) SA/CSB was not examined via the perspective of men affected by their female partners’ CSBs; (4); Participant perspectives and paper analyses digested mainly majority religions and did not include input from or expressions of traditional worldviews reflecting indigenous spirituality. In consequence, various points of view remain unexplored and are conceptualised here as fertile opportunities for future research.

Data Availability

The research data are not publicly available because participants were informed prior to interviews that their data would be stored securely and confidentially.

Notes

According to Fraser (2021), gaslighting is a form of psychological abuse in which someone controls and manipulates another person into doubting his or her own judgement or even sanity.

References

Agrimson, L. B., & Taft, L. B. (2009). Spiritual crisis: A concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65(2), 454–461. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04869.x

Arrey, A. E., Bilsen, J., Lacor, P., & Deschepper, R. (2016). Spirituality/Religiosity: A Cultural and Psychological Resource among Sub-Saharan African Migrant Women with HIV/AIDS in Belgium. PLoS ONE, 11(7), e0159488. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159488

Ballester-Arnal, R., Castro-Calvo, J., Gil-Llario, M. D., & Giménez-García, C. (2013). Relationship status as an influence on cybersex activity: Cybersex, youth, and steady partner. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 40(5), 444–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623x.2013.772549

Beck, R., & Haugen, A. D. (2012). The Christian religion: A theological and psychological review. APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality, (Vol 1): Context, theory, and research. https://doi.org/10.1037/14045-039

Beltrán-Morillas, A. M., Valor-Segura, I., & Expósito, F. (2015). El perdón ante transgresiones en las relaciones interpersonales [Forgiveness for transgressions in interpersonal relationships]. Psychosocial Intervention, 24(2), 71–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psi.2015.05.001

Beltrán-Morillas, A. M., Valor-Segura, I., & Expósito, F. (2019). Unforgiveness motivations in romantic relationships experiencing infidelity: Negative affect and anxious attachment to the partner as predictors. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00434

Bergner, R. M., & Bridges, A. J. (2002). The significance of heavy pornography involvement for romantic partners: Research and clinical implications. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 28(3), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/009262302760328235

Birrell, P., Bernstein, R., & Freyd, J. (2017). With the fierce and loving embrace of another soul. Reconstructing Meaning after Trauma. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-803015-8.00003-6

Blycker, G. (2023). Women’s wellbeing: Illuminating the harmful impact of a partner’s compulsive sexual behaviours. In F. Prever, G. Blycker, & L. Brandt (Eds.), Behavioural addiction in women: An international female perspective on treatment and research. Routledge.

Boyle, J. S. (1991). Field research: A collaborative model for practice and research. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483349015.n32

Bőthe, B., Tóth-Király, I., Griffiths, M. D., Potenza, M. N., Orosz, G., & Demetrovics, Z. (2021). Are sexual functioning problems associated with frequent pornography use and/or problematic pornography use? Results from a large community survey including males and females. Addictive Behaviors, 112, 106603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106603

Bożek, A., Nowak, P. F., & Blukacz, M. (2020). The relationship between spirituality, health-related behaviour, and psychological wellbeing. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01997

Braun-Courville, D. K., & Rojas, M. (2009). Exposure to sexually explicit web sites and adolescent sexual attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45(2), 156–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.12.004

Burke, L. A., Crunk, A. E., Neimeyer, R. A., & Bai, H. (2019). Inventory of complicated spiritual grief 2.0 (ICSG 2.0): Validation of a revised measure of spiritual distress in bereavement. Death Studies, 45(4), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2019.1627031

Burnay, J., Kepes, S., & Bushman, B. J. (2022). Effects of violent and nonviolent sexualized media on aggression-related thoughts, feelings, attitudes, and behaviors: A meta-ana- lytic review. Aggressive Behavior, 48(1), 111–136. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21998

Candler, D. (2022). Framed: Settling the gender agenda. Ocean Reeve Publishing.

Carnes, P. (1991). Don’t call it love: Recovery from sexual addiction. Bantam Books.

Carnes, P. (2000). Sexual addiction and compulsion: Recognition, treatment, and recovery. CNS Spectrums, 5(10), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1092852900007689

Carnes, P. (2015). The whole and the sum of the parts … towards a more inclusive understanding of divergences in sexual behaviours. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 22(2), 105–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2015.1050329

Carnes, P. (2018). Betrayal bond, revised: Breaking free of exploitive relationships. HCI.

Carnes, P. J. (2019). The sexual addiction screening process. Clinical Management of Sex Addiction. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315755267-4

Carnes, S., & Lee, M. A. (2014). Picking up the Pieces. Behavioural Addictions, 2014, 267–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-407724-9.00011-2

Charny, I. W., & Parnass, S. (1995). The impact of extramarital relationships on the continuation of marriages. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 21(2), 100–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926239508404389

Chen, J.-M., & Luetz, J. M. (2020). Mono-/Inter-/Multi-/Trans-/Anti-disciplinarity in research. In W. Leal Filho, A. Marisa Azul, L. Brandli, P. Gökcin Özuyar, T. Wall (Eds.), Quality education—Encyclopedia of the UN sustainable development goals (pp. 562–577). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95870-5_33

Chi, P., Tang, Y., Worthington, E. L., Chan, C. L., Lam, D. O., & Lin, X. (2019). Intrapersonal and interpersonal facilitators of forgiveness following spousal infidelity: A stress and coping perspective. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 75(10), 1896–1915. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22825

Clayton, R. B. (2014). The third wheel: The impact of Twitter use on relationship infidelity and divorce. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(7), 425–430. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2013.0570

Cooper, A., Delmonico, D. L., & Burg, R. (2000). Cybersex users, abusers, and compulsives: New findings and implications. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 7(1–2), 5–29.

Courtois, C., & Ford, J. (2014). Complex trauma across the lifespan. PsycEXTRA Dataset. https://doi.org/10.1037/e651052013-041

Creswell, J. W. (2015). Thirty essential skills for the qualitative researcher. Sage.

de Alarcón, R., de la Iglesia, J. I., Casado, N. M., & Montejo, A. L. (2019). Online porn addiction: What we know and what we don’t—A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(1), 91.

DePrince, A. P., Brown, L. S., Cheit, R. E., Freyd, J. J., Gold, S. N., Pezdek, K., & Quina, K. (2012). Motivated forgetting and misremembering: Perspectives from betrayal trauma theory. True and False Recovered Memories. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-1195-6_7

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2013). The landscape of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks.

Dillow, M. R., Malachowski, C. C., Brann, M., & Weber, K. D. (2011). An experimental examination of the effects of communicative infidelity motives on communication and relational outcomes in romantic relationships. Western Journal of Communication, 75(5), 473–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/10570314.2011.588986

Elkins, D. N., Hedstrom, L. J., Hughes, L. L., Leaf, J. A., & Saunders, C. (1988). Toward a humanistic-phenomenological spirituality. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 28(4), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167888284002

Exline, J. J., Park, C. L., Smyth, J. M., & Carey, M. P. (2011). Anger toward God: Social-cognitive predictors, prevalence, and links with adjustment to bereavement and cancer. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(1), 129–148. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021716

Exline, J. J., Prince-Paul, M., Root, B. L., & Peereboom, K. S. (2013). The spiritual struggle of anger toward God: A study with family members of hospice patients. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 16(4), 369–375. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2012.0246

Fernandez, D. P., Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2021). Lived experiences of recovery from compulsive sexual behaviour among members of sex and love addicts anonymous: A qualitative thematic analysis. Sexual Health & Compulsivity, 28(1–2), 47–80.

Fife, S. T., Weeks, G. R., & Stellberg-Filbert, J. (2013). Facilitating forgiveness in the treatment of infidelity: An interpersonal model. Journal of Family Therapy, 35(4), 343–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6427.2011.00561.x

Fincham, F. D., & May, R. W. (2017). Infidelity in romantic relationships. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 70–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.03.008

Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s search for meaning. Simon and Schuster.

Fraser, S. (2021). The toxic power dynamics of gaslighting in medicine. Canadian Family Physician, 67(5), 367–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.100

Freedman, S., & Zarifkar, T. (2016). The psychology of interpersonal forgiveness and guidelines for forgiveness therapy: Therapists need to know to help their clients forgive. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 3(1), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1037/scp0000087

Freyd, J. J. (1994). Betrayal trauma: Traumatic amnesia as an adaptive response to childhood abuse. Ethics & Behavior, 4(4), 307–329. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327019eb0404_1

Freyd, J. J. (1996). Betrayal trauma: The logic of forgetting childhood abuse. Harvard University Press.

Fusch, P., Fusch, G. E., & Ness, L. R. (2018). Denzin’s paradigm shift: Revisiting triangulation in qualitative research. Journal of Social Change, . https://doi.org/10.5590/josc.2018.10.1.02

Futrell, L. (2021). Is Porn the New Mistress? A Sexual Betrayal Study. California Institute of Integral Studies.

Giordano, A. L., & Cecil, A. L. (2014). Religious coping, spirituality, and hypersexual behavior among college students. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 21(3), 225–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2014.936542

Giorgi, A., Giorgi, B., & Morley, J. (2017). The descriptive phenomenological psychological method. In C. Willig (Ed.), (pp. 176–192). https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526405555.n11

Goertzen, L. R. (2003). Conceptualising forgiveness within the context of a reversal theory framework: The role of personality, motivation, and motion [Ph.D. dissertation, University of Windsor]. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2533&context=etd

Gómez, J., Smith, C., & Freyd, J. (2014). Minority students’ experience of discrimination and institutional betrayal. PsycEXTRA Dataset. https://doi.org/10.1037/e517672014-001

Gossner, J. D., Fife, S. T., & Butler, M. H. (2022). Couple healing from infidelity: A deductive qualitative analysis study. Sexual and Relationship Therapy.https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2022.2086231

Grøntvedt, T. V., Kennair, L. E., & Bendixen, M. (2020). Breakup likelihood following hypothetical sexual or emotional infidelity: Perceived threat, blame, and forgiveness. Journal of Relationships Research. https://doi.org/10.1017/jrr.2020.5

Grubbs, J. B., Hoagland, K. C., Lee, B. N., Grant, J. T., Davison, P., Reid, R. C., & Kraus, S. W. (2020). Sexual addiction 25 years on: A systematic and methodological review of empirical literature and an agenda for future research. Clinical Psychology Review, 82, 101925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101925

Grubbs, J. B., Perry, S. L., Wilt, J. A., & Reid, R. C. (2019). Pornography problems due to moral incongruence: An integrative model with a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(2), 397–415.

Hackett, C., Murphy, C., McClendon, D., & Shi, A. F. (2019). The gender gap in religion worldwide: Women are generally more religious than men particularly among Christians. In W. A. Mirola, M. O. Emerson, & S. C. Monahan (Eds.), Sociology of Religion. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315177458-6

Hall, P. (2016). Sex addiction: The partner’s perspective. Routledge.

Hastings, H. F., & Lucero Jones, R. (2023). Influence of a partner’s pornography consumption on a Christian woman’s sexuality: A qualitative exploration. Sexual Health & Compulsivity, 30(2), 143–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/26929953.2023.2176956

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (2017). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Interpersonal Development. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351153683-17

Herman, J. L. (1992). Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 5(3), 377–391. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490050305

Herman, J. L., & van der Kolk, B. A. (2020). Treating complex traumatic stress disorders in adults: Scientific foundations and therapeutic models. Guilford Publications.

Hills, K., Clapton, J., & Dorsett, P. (2016). Towards an understanding of spirituality in the context of nonverbal autism: A scoping review. Journal of Disability & Religion, 20(4), 265–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/23312521.2016.1244501

Holloway, M., & Jupp, P. (2020). Looking at death in the many contexts of life Margaret Holloway in conversation with Peter Jupp. Mortality, 25(1), 99–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576275.2019.1697659

Hukkinen, E., Lütz, J. M., & Dowden, T. (2023). Assessing research trends in spiritual growth: The case for self-determined learning. Religions, 14(6), 809. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14060809

Hulme, M. (2021). Climate change and science. Climate Change. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367822675-3

Husserl, E. (1970). The crisis of European sciences and transcendental phenomenology: An introduction to phenomenological philosophy. Northwestern University Press.

Jennings, T. L., Lyng, T., Gleason, N., Finotelli, I., & Coleman, E. (2021a). Compulsive sexual behavior, religiosity, and spirituality: A systematic review. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 10(4), 854–878. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2021.00084

Jennings, T. L., Lyng, T., Gleason, N., Finotelli, I., & Coleman, E. (2021b). Compulsive sexual behavior, religiosity, and spirituality: A systematic review. Journal of Behavioural Addictions, 10(4), 854–878. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2021.00084

Jha, A., & Banerjee, D. (2022). Neurobiology of sex and pornography addictions: A primer. Journal of Psychosexual Health, 4(4), 227–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/26318318221116042

Johnson, S. M., Makinen, J. A., & Millikin, J. W. (2001). Attachment injuries in couple relationships: A new perspective on impasses in couples therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 27(2), 145–155.

Kahn, L., & Freyd, J. (2008). Betrayal trauma: Theory and treatment implications. PsycEXTRA Dataset. https://doi.org/10.1037/e608922012-075

Kay, A. C., Gaucher, D., Napier, J. L., Callan, M. J., & Laurin, K. (2008). God and the government: Testing a compensatory control mechanism for the support of external systems. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(1), 18–35. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.95.1.18

Keffer, S. (2019). Intimate deception: Healing the wounds of sexual betrayal. Baker Books.

Kelley, L. P., Weathers, F. W., Mason, E. A., & Pruneau, G. M. (2012). Association of life threat and betrayal with posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25(4), 408–415. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21727

Kelly, J. D. (2018). Forgiveness: A key resiliency builder. Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research, 476(2), 203–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999.0000000000000024

King, S. (2003). The impact of compulsive sexual behaviors on clergy marriages: Perspectives and concerns of the pastor’s wife. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 10(2–3), 193–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/107201603902306307