Abstract

Visual sexual stimuli (VSS) are often used to induce affective responses in experimental research, but can also be useful in the assessment and treatment of sexual disorders (e.g., sexual arousal dysfunctions, paraphilic disorders, compulsive sexual behaviors). This systematic literature review of standardized sets containing VSS was conducted by searching electronic databases (PsycINFO, PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science) from January 1999 to December 2022 for specific keywords [("picture set" OR "picture database" OR "video set" OR "video database" OR "visual set" OR "visual database") AND ("erotic stimuli" OR "sexual stimuli" OR "explicit erotic stimuli" OR "explicit sexual stimuli")]. Selected sets were narratively summarized according to VSS (modality, duration, explicitness, shown sexes, sexual practices, physical properties, emotion models, affective ratings) and participants’ characteristics (gender, sexual orientation and sexual preferences, cultural and ethnic diversity). Among the 20 sets included, researchers can select from ~ 1,390 VSS (85.6% images, 14.4% videos). Most sets contain VSS of opposite- and some of same-sex couples, but rarely display diverse sexual practices. Although sexual orientation and preferences strongly influence the evaluation of VSS, little consideration of both factors has been given. There was little representation of historically underrepresented cultural and ethnic groups. Therefore, our review suggests limitations and room for improvement related to the representation of gender, sexual orientation, sexual preferences, and especially cultural and ethnic diversity. Perceived shortcomings in experimental research using VSS are highlighted, and recommendations are discussed for representative stimuli for conducting and evaluating sexual affective responses in laboratory and clinical contexts while increasing the replicability of such findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Experimental Research using Emotion Induction

Affective science often aims to evaluate and understand the dynamics and underlying mechanisms of emotional processes by inducing them with the help of various stimuli. Historically, researchers worldwide have developed specific stimuli to study emotions in experimental settings since the emergence of applied psychology in the late nineteenth century (Lang et al., 2008). However, it was not common practice for individual laboratories to share stimulus material with one another, leading to a major replication problem. Standardized stimuli for determining affective reactions can facilitate retesting in different laboratories around the world (Lang et al., 2008). As inducing specific emotions is a challenging task in experimental research, researchers must carefully select their stimuli to elicit specific affective states. Hence, the development of standardized and validated datasets of stimuli encourages scientific replication in emotion research and simplifies stimuli selection (Kim et al., 2018). Experimental research benefits from the use of standardized materials by producing replicable, comparable, and reliable results while also minimizing cross-cultural researcher bias (Horvat et al., 2014).

Stimuli are typically evaluated under experimental conditions using standardized affective rating scales. Such affective scales can be conceptualized and categorized in terms of discrete emotional states or described using a more dimensional approach (Ekman, 1992; Reisenzein, 1994). On one hand, dimensional models characterize core affect and the affective quality by degrees of valence and arousal (Bradley & Lang, 1994); on the other hand, discrete emotion categories typically assess feelings such as happiness, anger, fear, sadness, disgust, and surprise (Riegel et al., 2016).

Affective sets of visual stimuli (VS) have become increasingly popular in psychological, neuroscientific, and clinical research over the past four decades. The stimuli-viewing context has proven to be a powerful, cost-efficient, and eminently controllable experimental methodology, as settings can be changed and modulated based on how the content is presented. The use of visual tools has allowed us to advance our understanding of both normal and pathological emotional states (Kim et al., 2018; Lang et al., 2008). However, when presenting VS in an emotion elicitation experiment, it is important to consider what (e.g., diversity of sexual content), how (e.g., physical image properties of local brightness, color, or spatial frequency profile) and to whom (e.g., cultural variability) content is presented, as these factors may influence emotional processing (Delplanque et al., 2007; Matsumoto & Wilson, 2022; Redies et al., 2020; Verhavert et al., 2018).

Types of Sexual Stimuli and their Use in Sex Research

In sexuality research, the most common approach to induce sexual responses has been through visual stimuli (VS), primarily with pictures or videos (Stoléru et al., 2012). Images and videos are also the most predominant mediums for distributing and consuming sexual content nowaday, especially since viewing erotic content on the Internet has become increasingly common for large segments of the population (Ballester-Arnal et al., 2022).

Sexual stimuli are inherently salient and are considered highly arousing, typically eliciting strong activation of the appetitive system, resulting in high pleasure and arousal ratings as well as physiological reactions (Lang et al., 2008; Georgiadis & Kringelbach, 2012). However, there are also sexual stimuli that elicit a strong defensive reaction (Bradley et al., 2001; Lalumière et al., 2022). The defensive system is often activated in response to certain content, such as scenes depicting rape or abuse, affecting many individuals (Suschinsky & Lalumière, 2011).

Erotic preferences of the observer and sexual background play important yet understudied roles in the affective processing of sexual stimuli, being related to the observer's sexual and gender identity, as well as the picture content (Carrier Emond et al., 2019; Waisman et al., 2003; Wierzba, et al., 2015). Experimental and clinical studies using sexual visual material help to better understand human sexuality and its diversity (Stolerú et al., 2012). Additionally, this material can provide insights for evaluating and treating sexual disorders, such as paraphilic disorders, sexual arousal dysfunctions, or problematic pornography consumption (Carrier Emond et al., 2019; Meston et al., 2010; Sklenarik et al., 2019; Waismann et al., 2003).

Culture and Sexuality

Emotions can be both cross-culturally similar and different, depending on the specific domain of emotion studied and the context in which they are elicited (Matsumoto & Wilson, 2022). The diversity of ethnic and cultural backgrounds produces variations in how humans around the world perceive, experience, and express emotions. Additionally, an individual's identity and sexual diversity, influenced by cultural variables such as sexual double standards or cultural stigmas, are critical aspects of mental and physical health (Digoix et al., 2016; Friesen et al., 2017; Giménez-García et al., 2020, 2021; Nieva-Posso et al., 2023; Schmitt & Fuller, 2015).

Studies have shown that one's background and culture can affect their perspective and, subsequently, their emotional responses to various types of VS (Ismail et al., 2021). For example, Caucasian participants have been reported to react more strongly to film clips (Gabert-Quillen et al., 2015). Additionally, social class may play a significant role in the signaling or recognition of emotion, representing another understudied diversity factor (Monroy et al., 2022). Research examining the neural basis of emotions in relation to cultural influences suggests that neural representation may vary according to norms instilled by cultural backgrounds (Pugh et al., 2022). Previous research in sexuality indicates more pronounced cultural effects on sexual response patterns in women than men, and suggests that sexual responses may vary by ethnicity and depend on cultural context, particularly for women (Ganesan et al., 2020). However, there is little empirical data on understanding the social and cultural dimensions that may play an important role in VSS processing.

The Current Literature Review

Clinical psychological and neuroimaging studies, with a particular emphasis on sexuality, can benefit from a wide range of affective visual sexual stimuli (VSS). This is especially critical in the context of gender, sexual identity and orientation, as well as cultural backgrounds, as these intra- and interindividual differences may play a role in affective processing of VSS. Therefore, a scientific goal should be to have a variety of VSS to increase the number of questions that can be answered while using them. Standardized VSS should be used to replicate and compare results of different studies, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding. However, reviews and meta-analysis on human sexual responses (Georgiadis & Kringelbach, 2012; Poeppl et al., 2016; Stoléru et al., 2012; Ziogas et al., 2020) have shown that comparing different brain imaging studies is difficult because the stimuli used in each study are highly individualized. Therefore, this review intends to summarize the current availability of standardized sets with VSS to counteract such comparability problems.

Furthermore, one of the most difficult aspects of designing a study that seeks to elicit sexual responses is selecting appropriate emotional stimuli for often very specific research objectives. The recently published KAPODI-database of emotional stimuli has been designed as a tool to help researchers with the difficult considerations regarding appropriate stimulus selection (Diconne et al., 2022). However, no focus has been placed on stimuli of a sexual nature. Therefore, the objective of this study was to provide additional knowledge that specifically addresses the issues researchers face when studying emotion processes in human sexuality.

This systematic review aimed to help alleviate this methodological challenge and offer researchers a more informed decision about which stimulus set is best suited for their goals, as well as discuss what the future of sexuality research needs in terms of representative imaging in experimental settings. The objective of this literature review was to provide a detailed insight into the available standardized VSS, their quantity, and quality of provided information regarding sex, sexual orientation and preferences, ethnic and cultural diversity. We aimed to assess whether these are adequately serving the scientific community and if there is room for improvement.

Methods

Search Strategy

This systematic review was performed following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews) guidelines (Page et al., 2021). Initial scoping searches of the literature were conducted through PsycINFO (https://psycnet.apa.org/search), PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed), Scopus (Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands) and Web of Science (https://www.webofscience.com) to provide an overview of the visual sexual stimuli (VSS) in standardized sets.

The evaluation covered articles from January 1999 to December 2022 and included combinations of the following keywords: [("picture set" OR "picture database" OR "video set" OR "video database" OR "visual set" OR "visual database") AND ("erotic stimuli" OR "sexual stimuli" OR "explicit erotic stimuli" OR "explicit sexual stimuli")]. The start date was chosen because the standardization of visual stimuli for emotion research can be traced back to the development of the International Affective Picture System (IAPS) by Lang and colleagues, which was published in 1999. As an additional source, the bibliographies of studies identified during the search, which utilized VSS from standardized sets, were examined. This was necessary to identify further relevant affective VS sets that might include standardized VSS.

Eligibility Criteria

The exclusion and inclusion criteria for this systematic literature review are described below. Articles about affective VS sets without VSS were excluded, as well as those articles in which VSS were not standardized and made available to other researchers by publishing in a peer-reviewed journal. It is indeed common practice for VSS to be used in studies without researchers evaluating their affective value beforehand. Sometimes, VSS are rated by participants on affective scales during the experiment, but researchers do not plan to make these results available to others afterward due to the time-consuming nature of the process. Articles of this kind were excluded because we intended to report on sets that have been produced in a standardized and methodologically qualitative form with the primary goal to share them.

To be included in this review, the development of a standardized set of VS had to be the focus of the published work to ensure that methodological priority was also given to it. Regarding the inclusion criteria, articles were included in the systematic literature review if a standardization process for the set of VS was carried out and its development and validation were described in a coherent and credible way. This entails the full reporting of implementation, methods, and results in a manner that allows for replication, with results being available to other researchers either as publicly available information or upon request.

Identification and Selection of Standardized Affective Sets

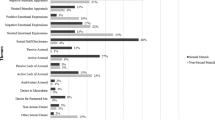

The literature was independently analyzed by two researchers. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram of our systematic literature review, which was adapted for the purpose of this study (Page et al., 2021). In total, 1307 records (422 PubMed; 30 Scopus; 1207 Web of Science; 11 Citations) were identified. Eventually, 389 were screened for their relevance. After a full text review, articles on standardized affective sets that did not meet our inclusion criteria were excluded. Subsequently, the standardized sets of affective VS and key attributes of their VSS were identified and compared. Each ultimately selected set of images (final n = 20) was analyzed according to stimuli and participants’ characteristics.

Adapted PRISMA flow chart (Page et al., 2021) of the screening and selection process

Data Extraction and Coding

VSS of the selected sets were first analyzed regarding (1) stimuli modality, (2) stimuli duration, (3) explicitness, (4) shown sexes and sexual content, and information provided to (5) physical properties, and employed (6) emotion models and affective ratings.

(1) Stimuli modality refers to the mode of presentation, whether videos or images were standardized. (2) Stimuli duration reports the time the stimuli were presented within the standardization procedures. (3) Explicitness stands for the intensity of the eroticism shown. Here, we distinguished non-sexual from sexual and sexually explicit and paraphilic (involving also dominance, coercion, and/or fetishes) content (Leonhardt et al., 2018). Every picture showing explicit sexual scenarios (e.g., oral sex, vaginal sex, etc.) fell into the sexually explicit category. On the other hand, sexually suggestive content with representations of nudity or sexual intimacy between individuals, even in the absence of nudity, was labeled as sexual. (4) The report on shown sexes and sexual content provides information on the sexes presented within the VSS sets (e.g., opposite-sex couples, male couples, female couples, or single males or females), and the sexual practices depicted. (5) The information about the provided physical properties gives an overview of whether the standardized sets contain data about pixel size, luminosity, color space, contrast, chromatic complexity, spatial frequency, and entropy. (6) Emotion models and affective ratings describe if the affective values obtained in the standardization process were from a dimensional emotion model (e.g., arousal, valence, or dominance) (Ekman, 1992; Reisenzein, 1994) or from a discrete emotion model (e.g., joy, amusement, anger, awe, contentment, disgust, excitement, fear, or sadness) (Riegel et al., 2016). Standardized sets may provide both dimensional and discrete ratings.

Furthermore, participants’ characteristics regarding representation of gender, sexual orientation, sexual preferences, as well as ethnic and cultural diversity, were described in depth.

Results

Characteristics of the Standardized Sets of Visual Stimuli

Twenty standardized sets fit into the previously defined criteria and were analyzed. Relevant characteristics of the included standardized sets with VSS are described in Table 1. Table 2 summarizes the principal characteristics of the included studies in terms of participants' characteristics. Within the tables, the selected standardized sets are sorted chronologically according to the articles’ publication date regarding the standardization process.

All of the standardization studies focused on non-clinical populations (i.e., college students, undergraduate university students, members of the general public, community members, and healthy populations), apart from those studies reporting affective ratings of child sexual offenders (Dombert et al., 2013; Laws & Gress, 2004; Renaud et al., 2010). The mean age of the study samples ranged between 19.3 and 45.5 years.

Gender, Sexual Orientation, and Sexual Preferences

With regards to the participant characteristics, most VS sets included in this systematic review (n = 15) had women and men participating in the standardization process. There were two sets each reporting a sample consisting of only women (Gómez-Lugo et al., 2016; Jacob et al., 2011) or only men (Daoultzis & Kordoutis, 2022; Vallejo-Medina et al., 2017). The NRP set (Laws & Gress, 2004) did not offer any information in this regard. Regarding the sex of the individuals depicted in the VSS, 14 sets offered scenes of opposite-sex couples, six sets included female couples, five sets male couples, 13 sets solo male, and 12 sets solo female figures.

Nine sets provided information about the sexual orientation of the participants. Among them, most respondents were heterosexual, followed by homosexual and bisexual participants. The majority of the VSS showed dressed, scarcely dressed, or nude couples, and single individuals in sexually suggestive settings. Furthermore, representations of foreplay, masturbation, cunnilingus, fellatio, coital sex, and anal sex were included. Regarding paraphilic media, researchers can draw upon illustrations of sexualized dominance and imagery of children. Finally, there were three sets that consist of computer-generated images of non-real people: the NRP (Laws & Gress, 2004), the 3D set (Renaud et al., 2010), and the VPS (Dombert et al., 2013). They were developed primarily to serve as assessment materials for pedophilic sexual interests as the VS differ in stages of pubertal development (i.e., the development of primary and secondary sexual characteristics) and were also rated by individuals with such sexual preferences.

Ethnic and Cultural Diversity

A minority (n = 2) of the included sets has been normed in other than the ethnocultural groups other than those of the original studies. The IAPS has been validated in various countries including Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brazil, Chile, China, Germany, Hungary, Japan, Korea, Mexico, Portugal, South Africa, and Spain (Deák et al., 2010; Drace et al., 2013; Gong et al., 2018; Grühn & Scheibe, 2008; Kwon et al., 2009; Liu & XU, 2006; Madera-Carrillo et al., 2022; Molina et al., 2018; Moltó et al., 1999, 2013; Nestadt et al., 2022; Porto et al., 2008; Ribeiro et al., 2005; Silva, 2011; Soares et al., 2015; Ueno et al., 2019; Verschuere et al., 2001; Vila et al., 2001). The emotionally evocative short videos of Cowen and Keltner (2017) have been validated and compared in Japan, the USA, Canada, and Europe (Cowen et al., 2021).

Most sets were standardized in English (n = 7), followed by Spanish (n = 5), Italian (n = 2), and German (n = 2). Further languages used for the standardized sets are Chinese (n = 1), Polish (n = 1), Portuguese (n = 1), French (n = 1), Greek (n = 1), and Finnish (n = 1). The respective standardization processes took place in the USA (n = 4), Canada (n = 3), Spain (n = 3), Germany (n = 2), Colombia (n = 2), Italy (n = 2), Poland (n = 1), Finland (n = 1), China (n = 1), South Africa (n = 1), and Greece (n = 1). Most studies (n = 16) did not report on the ethnicity of their participants.

Discussion

Inducing emotional responses by visual sexual stimuli (VSS) is a common approach in sexuality research (van’t Hof, & Cera, 2021; Georgiadis & Kringelbach, 2012; Poeppl et al., 2016; Stoléru et al., 2012; Ziogas et al., 2020). At the time of the literature search, twenty standardized sets containing (VSS) were identified, comprising approximately 1,390 VSS in total. Yet, only nine research groups have engaged in developing standardized datasets with a particular focus on VSS, namely the NRP set (Laws & Gress, 2004), the 3D set (Renaud et al., 2010), the stimuli set of Jacob et al. (2011), the VPS (Dombert et al., 2013), the NAPS ERO (Wierzba et al., 2015), the sets of Gómez-Lugo et al. (2016) and Vallejo-Medina et al. (2017), the East Asian Erotic Picture Dataset (Cui et al., 2021), and the SOBEM (Ruzzante et al., 2022).

Inclusivity of Gender, Sexual Orientation, and Sexual Preferences

The standardized sets including sexual stimuli currently available offer limited diversity in terms of gender, sexual orientation, sexual preferences, or sexual practices. However, the need for more diversity and representation extends beyond just the content of the VSS to include the experimental samples that rate such stimuli. Research has demonstrated that factors such as gender, sexual orientation, and sexual preferences significantly influence the emotion elicitation and rating process of VSS (Rupp & Wallen, 2008; van’t Hof & Cera, 2021; van’t Hof et al., 2022; Ziogas et al., 2020).

Some of the reported standardized stimuli sets are exclusively suited for specific target groups or research interests, severely limiting their usefulness for research on other populations. For instance, the set developed by Jacob et al. (2011) can only be considered appropriate for research on heterosexual female participants and for studying sexual responses to non-explicit content. A major issue concerning the existing standardized stimuli is the lack of consideration for sexual orientations other than heterosexuality, resulting in a notable bias towards investigating young heterosexual individuals. Only the 3D Set (Renaud et al., 2010), the VPS (Dombert et al., 2013), and the NAPS ERO (Wierzba et al., 2015) intended to create a somewhat balanced sample of heterosexual, bisexual, or homosexual participants. However, the majority of the sets do not even provide information on the sexual orientation of their sample. Few studies can offer validated stimuli suitable for studying sexual responses of non-heterosexual individuals (homosexual, bisexual, etc.) or provide ratings on their stimuli from individuals with other gender identities (e.g., transgender), despite the clear influence of sex, gender, and sexual identity on sexual behavior (Digoix et al., 2016; Giménez-García et al., 2020, 2021; Nieva-Posso et al., 2023; Schmitt & Fuller, 2015). Additionally, most neuroimaging studies on sexual behavior have been conducted with male rather than female participants, leading to male-based models (van't Hof & Cera, 2021). The review by van't Hof & Cera (2021) on this issue provides recommendations on methodological choices that might influence brain responses to sexual stimuli in women and advocates for the development of new sexual stimuli selected by women. Therefore, an important consideration is the representation and inclusion of individuals with different sexual orientations and gender identities, which should be addressed at all stages of future standardization processes.

It is widely recognized that stimuli can evoke vastly different emotional responses across individuals or contexts (Lang et al., 2008). A particular sexual visual stimulus may elicit feelings of desire and wanting in some individuals, while others may find it unpleasant or even disgusting and morally unacceptable. In this regard, VSS sets related to paraphilias, such as the NRP (Laws & Gress, 2004), VPS (Dombert et al., 2013), and the 3D set (Renaud et al., 2010), offer opportunities for assessing pedophilic sexual interest. Specialized materials and participant samples are needed for the evaluation process to identify common features of specific paraphilias and provide insights into their etiology and treatment. Computer-generated images are particularly useful for experimental research into pedophilic sexual interest and are generally considered ethically appropriate for research purposes in most countries, as they involve virtual avatars (Dombert et al., 2013). Regarding other types of paraphilic interests, only the IAPS contained a few VSS of sexual scenarios depicting scenarios of dominance or coercion, which may be associated with paraphilic interests involving non-consenting content. However, it is crucial to differentiate consensual sadomasochism from coercive sexual acts (Moser, 2018).

As the dissemination of nudity becomes more normalized in our society, pornography consumption is beginning at younger ages and increasing in frequency, leading to a certain desensitization (Ballester-Arnal et al., 2022). In this context, nude images devoid of explicit sexual content may lose their ability to evoke arousal in individuals. As society becomes more sexually diverse and inclusive of various sexual orientations and gender identities, there is a growing need for erotic material that reflects this diversity by portraying a range of sexual situations, accommodating the continuum of sexual preferences. Many of the available sets depict scarcely dressed or nude couples and individuals engaged in suggestive activities. Some sets include scenarios involving foreplay, masturbation, cunnilingus, fellatio, coital sex, and occasionally anal sex. Additionally, the MATTER set (Ruiz-Padial et al., 2021) includes some images featuring sex toys. However, the current standardized sets do not cover other types of sexual interests commonly found on pornography websites, such as sexual roleplays, group sex, or BDSM (Hald & Štulhofer, 2016). These scenarios could be particularly relevant for studying pornography consumption.

Despite the significant influence of sexual orientation and preferences on the evaluation of sexual content, these factors have been largely overlooked in existing sets, both in participant recruitment and stimulus representation. The wide array of sexual interests and emotional responses to sexual stimuli underscores the necessity for diverse visual material, encompassing varying levels of explicitness, sexual scenarios, practices, and depicted sexes. However, many available visual sexual stimuli exhibit striking similarities, particularly concerning explicitness and sexual practices. This lack of diversity fails to accurately reflect real-life preferences and the sexual realities of many individuals.

Exploration of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity

Ethnic and cultural diversity has been largely overlooked in the reviewed standardized stimulus material, with only two standardized sets of VSS found that did not predominantly depict White individuals: the East Asian Erotic Picture Dataset (Cui et al., 2021) and the SA-APS (Nestadt et al., 2022). Moreover, only a small proportion of standardized sets reported participant race and ethnicity. Further validation studies involving diverse populations, particularly those from historically underrepresented cultural, ethnic, educational, and socioeconomic backgrounds, are imperative. Equitable representation of participants from diverse racial and ethnic groups is essential to enhance inclusivity in the scientific process and improve the generalizability of results. Currently, only the IAPS stimuli and the evocative videos from Cowen and Keltner have been validated in further ethnocultural groups, revealing further cross-cultural variations in self-reported emotional experiences (Cowen et al., 2021; Deák et al., 2010; Gong et al., 2018; Kwon et al., 2009; Liu & XU, 2006; Porto et al., 2008; Ribeiro et al., 2005; Ueno et al., 2019).

Future studies should broaden and adapt temporal, geographical, and cultural contexts to mitigate bias toward specific nationalities and ethno-cultural backgrounds, thereby improving the reliability of the sets. Cultural differences in emotional stimuli processing may play an important role in adequate selection of emotional stimuli. Examining the effects of culture and context on the processing of VSS would be facilitated if pre-assessed stimulus material was available.

Comparability and Replication Issues

VS have many advantages over other methods as they are manifoldly applicable and cost-efficient in eliciting specific emotions and associated physiological responses (Kim et al., 2018; Lang et al., 1993). Furthermore, affective VS sets provide simple, low-cost, and efficient means to scientifically study emotional impact (Villani & Riva, 2012). All mentioned sets are freely available to the research community, which facilitates some degree of replication and methodological control in studies and experimental research.

Apart from using these sets, researchers who specifically want to study responses to VSS can also compile their own stimuli, which has many disadvantages (e.g., time-consuming, lack of comparability, etc.) and often leads to unpublished datasets with very limited information about the image selection process. Nevertheless, this happens very frequently in studies working with VSS (e.g., Carrier Emond et al., 2019; Meston et al., 2010; Sklenarik et al., 2019; Waismann et al., 2003). Such sets of stimuli are sometimes available on request but do not offer a standardized behavioral or reporting protocol, thus not fully describing the creation and validation of the stimuli, or indeed at all. Researchers often use unstandardized stimuli due to the paucity of adequate stimuli available in standardized sets. However, differences in study methodologies related to human sexual processing are a source of errors in meta-analytic approaches, making comparability difficult (van’t Hof, & Cera, 2021; Georgiadis & Kringelbach, 2012; Poeppl et al., 2016; Stoléru et al., 2012; Ziogas et al., 2020).

Moreover, experimental approaches (e.g., fMRI, EEG) usually require a high repetition rate of conditions, and specific stimuli cannot be presented too often. This emphasizes the need for introducing additional sets to avoid habituation and to provide sufficient stimuli of diverse motifs. Research laboratories using affective stimuli to study emotion in diverse psychopathological disorders and clinical psychological studies with a particular emphasis on sexuality can benefit from a wide range of diverse sexual imagery in terms of sexual preferences as well as cultural and ethnic diversity. Sexual disorders such as sexual arousal dysfunctions, paraphilia, compulsive sexual behaviors, and problematic pornography consumption could be exposed to new research questions with adequate and reliable sets of diverse sexual content.

The use of standardized stimuli affords the ability to compare and highlight consistencies and inconsistencies between different findings. For accurate comparisons across different studies, standardized protocols are very useful, and studies focused on sexual topics are especially lacking in material. Future studies should bear in mind the need for affective VS, specifically dealing with human sexuality and the lack of sets containing diverse sexual content to better understand intra- and interindividual differences in sexual responses. Undoubtedly, sex is a complex stimulus. Nevertheless, it should be considered a future goal to offer comprehensive sets of VSS adequate for the current state of knowledge in the field, bridging between sexuality, diversity, and emotion.

Limitations and Conclusions

This literature review highlights both the need for and the insufficient use of standardized stimuli in the field of human sexuality, pointing to the necessity for the development of new and more diverse VSS specifically designed for the induction and assessment of sexual affective responses in clinical and laboratory contexts. Although understanding the processing of VSS has become a significant focus in research on human sexuality, insufficient attempts have been made to provide other researchers with sexual material that has been tested, standardized, and is ready to be used as an emotion induction tool in experimental research paradigms investigating human sexuality. A variety of modern VSS could open a new world of possible questions and therefore greatly expand the amount of further data that can be collected.

One limitation of the current PRISMA review is its focus solely on VSS. Future studies should also consider the development of standardized media beyond visual stimuli, such as audio, tactile, or olfactory materials. Additionally, while this review concentrated on the representation and variations in the affective perception of sexual emotional content related to gender, sexual orientation, sexual preferences, as well as culture and ethnicity, other influences may also be of importance (e.g., age, occupation, education).

In summary, there is a clear need for additional normative datasets containing affective VSS to address several crucial objectives: (1) facilitating easier and more effective experimental control in the selection of emotional stimuli, (2) enabling comparisons of results across different studies conducted in various laboratories, (3) supporting replication efforts within and between research laboratories focusing on sexual processes, and (4) promoting inclusivity in sexuality research concerning gender, sexual orientation, sexual preferences, as well as cultural and ethnic diversity. The absence of such diversity seriously compromises the validity of the results obtained in previous research, as it introduces biases from an ethnocentric, androcentric, and cis-heterocentric perspective. This failure to embrace diversity contributes to a lack of understanding of the experiences of individuals who deviate from dominant societal norms regarding sexuality. Furthermore, it perpetuates social discrimination and undermines the purported neutrality and objectivity of scientific inquiry, leaving the multiple ways that human beings have to construct their sexuality invisible. Consequently, addressing these shortcomings is imperative to ensure ethical and comprehensive research practices in the field of human sexuality.

The development of more sophisticated and comprehensive standardized sets of VSS has the potential to significantly advance research in the field of human sexuality. By providing researchers with readily available and well-represented stimuli, such sets can streamline the process of creating experimental materials and facilitate the replication of procedures used in previous studies. Furthermore, there is a pressing need for further empirical work to establish norms for different demographic groups, particularly in relation to sexual orientation and cultural-ethnic diversity. Such research efforts would not only enhance inclusivity but also contribute to a better understanding of systematic interindividual differences in the evaluation of emotional stimuli. Ultimately, this knowledge could shed light on the structure, function, and development of emotions, offering valuable insights into human sexuality and its complexities.

In conclusion, this review underscores methodological limitations and an underrepresentation of diversity in previously standardized sets and validated VS for the field of human sexuality. To ensure success and representativeness, it is crucial to provide researchers with reliable metrics when selecting stimuli for studies exploring subjective, behavioral, and psychophysiological reactions related to human sexuality. Building new standardized, emotionally evocative, internationally accessible sets focused on diverse sexual content and raters –encompassing gender, sexual orientation, sexual preferences, depicted ethnicities, and cultures– and employing them more frequently in experimental research should be prioritized. Diversifying VSS will expand the scope of questions that can be addressed in research, thereby advancing our understanding of human sexuality.

References

Ack Baraly, K. T., Muyingo, L., Beaudoin, C., Karami, S., Langevin, M., & Davidson, P. S. (2020). Database of emotional videos from Ottawa (DEVO). Collabra: Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.180

Ballester-Arnal, R., García-Barba, M., Castro-Calvo, J., Giménez-García, C., & Gil-Llario, M. (2022). Pornography consumption in people of different age groups: An analysis based on gender, contents, and consequences. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-022-00720-z

Bradley, M. M., Codispoti, M., Cuthbert, B. N., & Lang, P. J. (2001). Emotion and motivation I: Defensive and appetitive reactions in picture processing. Emotion, 1(3), 276.

Bradley, M. M., & Lang, P. J. (1994). Measuring emotion: The self-assessment manikin and the semantic differential. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 25(1), 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7916(94)90063-9

Bradley, M. M., & Lang, P. J. (2017). International affective picture system. Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_42-1

Carvalho, S., Leite, J., Galdo-Álvarez, S., & Gonçalves, O. F. (2012). The emotional movie database (EMDB): A self-report and psychophysiological study. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 37(4), 279–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-012-9201-6

Carretié, L., Tapia, M., López-Martín, S., & Albert, J. (2019). EmoMadrid: An emotional pictures database for affect research. Motivation and Emotion, 43, 929–939. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-019-09780-y

Carrier Emond, F., Nolet, K., Rochat, L., Rouleau, J. L., & Gagnon, J. (2019). Inhibitory control in sexually coercive men: Behavioral insights using a stop-signal task with neutral, emotional, and erotic stimuli. Sexual Abuse: Journal of Research and Treatment. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063219825866

Ciardha, C. Ó., Attard-Johnson, J., & Bindemann, M. (2018). Latency-based and psychophysiological measures of sexual interest show convergent and concurrent validity. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(3), 637–649. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-1133-z

Cowen, A. S., & Keltner, D. (2017). Self-report captures 27 distinct categories of emotion bridged by continuous gradients. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(38), E7900–E7909. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1702247114

Cowen, A. S., & Keltner, D. (2021). Semantic space theory: A computational approach to emotion. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 25(2), 124–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2020.11.004

Cowen, A., Prasad, G., Tanaka, M., Kamitani, Y., Kirilyuk, V., Somandepalli, K., Jou, B., Schroff, F., Hartwig, A., Brooks, J.A., & Keltner, D. (2021). How emotion is experienced and expressed in multiple cultures: a large-scale experiment. PsyArXiv.

Cui, Q., Wang, Z., Zhang, Z., & Li, Y. (2021). The East Asian erotic picture dataset and gender differences in response to opposite-sex erotic stimuli in chinese college students. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648271

Daoultzis, K. C., & Kordoutis, P. (2022). A pilot study testing a new visual stimuli database for probing men’s gender role conflict: GRASP (Gender Role Affective Stimuli Pool). Journal of Homosexuality. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2022.2104147

Deák, A., Csenki, L., & Révész, G. (2010). Hungarian ratings for the international affective picture system (IAPS): A cross-cultural comparison. Empirical Text and Culture Research, 4(8), 90–101.

Delplanque, S., N’diaye, K., Scherer, K., & Grandjean, D. (2007). Spatial frequencies or emotional effects?: A systematic measure of spatial frequencies for IAPS pictures by a discrete wavelet analysis. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 165(1), 144–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.05.030

Diconne, K., Kountouriotis, G. K., Paltoglou, A. E., Parker, A., & Hostler, T. J. (2022). Presenting KAPODI–The searchable database of emotional stimuli sets. Emotion Review, 14(1), 84–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/17540739211072803

Digoix, M., Franchi, M., Pichardo Galán, J. I., Selmi, G., de Stéfano Barbero, M., Thibeaud, M., & Vela, J. A. (2016). Sexual orientation, family and kinship in France, Iceland, Italy and Spain. Families and Societies Working Paper, 54.

Dombert, B., Mokros, A., Brückner, E., Schlegl, V., Antfolk, J., Bäckström, A., Zappalà, A., Osterheider, M., & Santtila, P. (2013). The virtual people set. Sexual Abuse A Journal of Research and Treatment. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063212469062

Drace, S., Efendić, E., Kusturica, M., & Landžo, L. (2013). Cross-cultural validation of the “International Affective Picture System”(IAPS) on a sample from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Psihologija, 46(1).

Ekman, P. (1992). Are there basic emotions? Psychological Review, 99(3), 550–553. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.99.3.550

Friesen, A., Smith, K. B., & Hibbing, J. R. (2017). Physiological arousal and self-reported valence for erotica images correlate with sexual policy preferences. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 29(3), 449–470. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edw008

Gabert-Quillen, C. A., Bartolini, E. E., Abravanel, B. T., & Sanislow, C. A. (2015). Ratings for emotion film clips. Behavior Research Methods, 47, 773–787.

Ganesan, A., Morandini, J. S., Veldre, A., Hsu, K. J., & Dar-Nimrod, I. (2020). Ethnic differences in visual attention to sexual stimuli among Asian and White heterosexual women and men. Personality and Individual Differences, 155, 109630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.109630

Georgiadis, J. R., & Kringelbach, M. L. (2012). The human sexual response cycle: Brain imaging evidence linking sex to other pleasures. Progress in Neurobiology, 98, 49–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.05.004

Giménez-García, C., Castro-Calvo, J., Gil-Llario, M. D., & Ballester-Arnal, R. (2020). Sexual relationships in hispanic countries: A literature review. Current Sexual Health Reports, 12(3), 83–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-020-00272-6

Giménez-García, C., Nebot-Garcia, J. E., Ruiz-Palomino, E., García-Barba, M., & Ballester-Arnal, R. (2021). Spanish women and pornography based on different sexual orientation: An analysis of consumption, arousal, and discomfort by sexual orientation and age. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 19, 1228–1240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00617-3

Gong, X., Wong, N., & Wang, D. (2018). Are gender differences in emotion culturally universal? Comparison of emotional intensity between Chinese and German samples. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 49(6), 993–1005. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022118768434

Gómez-Lugo, M., Saavedra-Roa, A., Pérez-Durán, C., & Vallejo-Medina, P. (2016). Validity and reliability of a set of sexual stimuli in a sample of Colombian heterosexual young women. Suma Psicológica, 23(2), 109–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sumpsi.2016.09.001

Grühn, D., & Scheibe, S. (2008). Age-related differences in valence and arousal ratings of pictures from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS): Do ratings become more extreme with age? Behavior Research Methods, 40(2), 512–521. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.2.512

Hald, G. M., & Štulhofer, A. (2016). What types of pornography do people use and do they cluster? Assessing types and categories of pornography consumption in a large-scale online sample. The Journal of Sex Research, 53(7), 849-859.

Harmon-Jones, E., Harmon-Jones, C., & Summerell, E. (2017). On the importance of both dimensional and discrete models of emotion. Behavioral Sciences, 7(4), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7040066

Horvat, M., Bogunović, N., & Ćosić, K. (2014). STIMONT: A core ontology for multimedia stimuli description. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 73(3), 1103–1127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-013-1624-4

Ismail, S. N. M. S., Aziz, N. A. A., Ibrahim, S. Z., Khan, C. T., & Rahman, M. A. (2021). Selecting video stimuli for emotion elicitation via online survey. Human-Centric Computing and Information Sciences, 11(36), 1–18.

Jacob, G. A., Arntz, A., Domes, G., Reiss, N., & Siep, N. (2011). Positive erotic picture stimuli for emotion research in heterosexual females. Psychiatry Research, 190, 348–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2011.05.044

Kim, H., Lu, X., Costa, M., Kandemir, B., Adams, R. B., Jr., Li, J., Wang, J. Z., & Newman, M. G. (2018). Development and validation of Image Stimuli for Emotion Elicitation (ISEE): A novel affective pictorial system with test-retest repeatability. Psychiatry Research, 261, 414–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.12.068

Kragel, P. A., Reddan, M. C., LaBar, K. S., & Wager, T. D. (2019). Emotion schemas are embedded in the human visual system. Science Advances, 5(7), eaaw4358.

Kurdi, B., Lozano, S., & Banaji, M. R. (2017). Introducing the open affective standardized image set (OASIS). Behavior Research Methods, 49(2), 457–470. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-016-0715-3

Kwon, Y., Scheibe, S., Samanez-Larkin, G. R., Tsai, J. L., & Carstensen, L. L. (2009). Replicating the positivity effect in picture memory in Koreans: Evidence for cross-cultural generalizability. Psychology and Aging, 24(3), 748. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016054

Lalumière, M. L., Sawatsky, M. L., Dawson, S. J., & Suschinsky, K. D. (2022). The empirical status of the preparation hypothesis: Explicating women’s genital responses to sexual stimuli in the laboratory. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(2), 709–728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-01599-5

Lang, P. J., Bradley, M. M., & Cuthbert, B. N. (1999). International affective picture system (IAPS): Technical manual and affective ratings. University of Florida.

Lang, P. J., Bradley, M. M., & Cuthbert, B. N. (2008). International Affective Picture System (IAPS): Instruction manual and affective ratings, Technical Report A-8. Gainesville: The Center for Research in Psychophysiology. University of Florida.

Lang, P. J., Greenwald, M. K., Bradley, M. M., & Hamm, A. O. (1993). Looking at pictures: Affective, facial, visceral, and behavioral reactions. Psychophysiology, 30, 261–273.

Laws, D. R., & Gress, C. L. (2004). Seeing things differently: The viewing time alternative to penile plethysmography. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 9, 183–196. https://doi.org/10.1348/1355325041719338

Leonhardt, N. D., Spencer, T. J., Butler, M. H., & Theobald, A. C. (2018). An organizational framework for sexual media’s influence on short-term versus long-term sexual quality. Archives of Sexual Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1209-4

Liu, X., & Xu, A. (2006). Native research of international affective picture system: Assessment in university students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Madera-Carrillo, H., De Rivera, D. Z. E., Ruiz-Díaz, M., Berriel-Saez-de-Nanclares, P., & González, J. I. G. (2022). Caracterización del International Afectiva Picture System (IAPS) en población mexicana. Implicación de la etiquetación en la valoración emocional. Revista Mexicana de Investigación en Psicología, 14(1).

Maffei, A., & Angrilli, A. (2019). E-MOVIE-Experimental MOVies for Induction of Emotions in neuroscience: An innovative film database with normative data and sex differences. PLoS ONE, 14(10), e0223124. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223124

Matsumoto, D., & Wilson, M. (2022). A half-century assessment of the study of culture and emotion. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 53(7–8), 917–934. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220221221084236

Meston, C. M., Rellini, A. H., & McCall, K. (2010). The sensitivity of continuous laboratory measures of physiological and subjective sexual arousal for diagnosing women with sexual arousal disorder. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(2), 938–950.

Molina, J., Ribeiro, R. L., Santos, F. H., & Len, C. A. (2018). Classification of the international affective picture system (IAPS) images for teenagers of the city of São Paulo. Psychology & Neuroscience, 11(1), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1037/pne0000123

Moltó, J., Montañés, S., Poy, R., Segarra, P., Pastor, M. C., & Tormo, M. P. (1999). Un nuevo método para el estudio experimental de las emociones: El International Affective Picture System (IAPS). Adaptación española. Baremos nacionales. Iberpsicología: Revista Electrónica de la Federación española de Asociaciones de Psicología, 5(1), 8.

Moltó, J., Segarra, P., López, R., Esteller, À., Fonfría, A., Pastor, M. C., & Poy, R. (2013). Adaptación eapañola del" International Affective Picture System" (IAPS). Tercera parte. Anales De Psicología/annals of Psychology, 29(3), 965–984.

Monroy, M., Cowen, A. S., & Keltner, D. (2022). Intersectionality in emotion signaling and recognition: The influence of gender, ethnicity, and social class. Emotion, 22(8), 1980–1988. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0001082

Moser, C. (2018). Paraphilias and the ICD-11: Progress but still logically inconsistent. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(4), 825–826. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-1141-z

Nestadt, A. E., Kantor, K., Thomas, K. G., & Lipinska, G. (2022). A South African adaptation of the international affective picture system: The influence of socioeconomic status and education level on picture ratings. Behavior Research Methods. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-022-01994-2

Nieva-Posso, D. A., Arias-Castillo, L., & García-Perdomo, H. A. (2023). Transgender Clinic: The Importance of a Diverse Medicine. Sexuality & Culture, 1–4.

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Poeppl, T. B., Langguth, B., Rupprecht, R., Laird, A. R., & Eickhoff, S. B. (2016). A neural circuit encoding sexual preference in humans. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 68, 530–536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.06.025

Porto, W. G., Bertolucci, P., Ribeiro, R. L., & Bueno, O. F. A. (2008). Subjective affective ratings to photographic stimuli of the International Affective Picture System in a Brazilian elderly sample. Revista De Psiquiatria Do Rio Grande Do Sul, 30, 131–138. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-81082008000300009

Prause, N., Moholy, M., & Staley, C. (2014). Biases for affective versus sexual content in multidimensional scaling analysis: An individual difference perspective. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(3), 463–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0128-7

Pugh, Z. H., Choo, S., Leshin, J. C., Lindquist, K. A., & Nam, C. S. (2022). Emotion depends on context, culture and their interaction: Evidence from effective connectivity. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 17(2), 206–217. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsab092

Redies, C., Grebenkina, M., Mohseni, M., Kaduhm, A., & Dobel, C. (2020). Global image properties predict ratings of affective pictures. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(May), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00953

Reisenzein, R. (1994). Pleasure-arousal theory and the intensity of emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 525–539. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.3.525

Renaud, P., Rouleau, J. L., Proulx, J., Trottier, D., Goyette, M., Bradford, J. P., Fedoroff, P., Dufresne, M. H., Dassylva, B., Côté, G., & Bouchard, S. (2010). Virtual characters designed for forensic assessment and rehabilitation of sex offenders: standardized and made-to-measure. JVRB-Journal of Virtual Reality and Broadcasting. https://doi.org/10.20385/1860-2037/7.2010.5

Ribeiro, R. L., Pompéia, S., & Bueno, O. F. A. (2005). Comparison of brazilian and american norms for the international affective picture system (IAPS). Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry, 27, 208–215.

Riegel, M., Żurawski, Ł, Wierzba, M., Klocek, Ł, Horvat, M., Grabowska, A., Michałowski, J., Jednoróg, K., & Marchewka, A. (2016). Characterization of the Nencki Affective Picture System by discrete emotional categories (NAPS BE). Behavior Research Methods, 48(2), 600–612. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-015-0620-1

Ruiz-Padial, E., Pastor, M. C., Mercado, F., Mata-Martín, J. L., & García-León, A. (2021). MATTER in emotion research: Spanish standardization of an affective image set. Behavior Research Methods, 53(5), 1973–1985. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-021-01567-9

Rupp, H. A., & Wallen, K. (2008). Sex differences in response to visual sexual stimuli: A review. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37(2), 206–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-007-9217-9

Rupp, H. A., & Wallen, K. (2009). Sex-specific content preferences for visual sexual stimuli. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38, 417–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-008-9402-5

Ruzzante, D., Monachesi, B., Orabona, N., & Vaes, J. (2022). The Sexual OBjectification and EMotion database: A free stimulus set and norming data of sexually objectified and non-objectified female targets expressing multiple emotions. Behavior Research Methods, 54(2), 541–555. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-021-01640-3

Schmitt, D. P., & Fuller, R. C. (2015). On the varieties of sexual experience: Cross-cultural links between religiosity and human mating strategies. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 7(4), 314–326. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000036

Silva, J. R. (2011). International Affective Picture System (IAPS) in Chile: A crosscultural adaptation and validation study. Terapia Psicologica, 29(2), 251–258.

Sklenarik, S., Potenza, M. N., Gola, M., Kor, A., Kraus, S. W., & Astur, R. S. (2019). Approach bias for erotic stimuli in heterosexual male college students who use pornography. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 8(2), 234–241. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.8.2019.31

Soares, A. P., Pinheiro, A. P., Costa, A., Frade, C. S., Comesaña, M., & Pureza, R. (2015). Adaptation of the international affective picture system (IAPS) for European Portuguese. Behavior Research Methods, 47(4), 1159–1177. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-014-0535-2

Stoléru, S., Fonteille, V., Cornélis, C., Joyal, C., & Moulier, V. (2012). Functional neuroimaging studies of sexual arousal and orgasm in healthy men and women: A review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 36(6), 1481–1509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.03.006

Suschinsky, K. D., & Lalumière, M. L. (2011). Prepared for anything? An investigation of female genital arousal in response to rape cues. Psychological Science, 22, 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610394660

Ueno, D., Masumoto, K., Sato, S., & Gondo, Y. (2019). Age-related differences in the International Affective Picture System (IAPS) valence and arousal ratings among Japanese individuals. Experimental Aging Research, 45(4), 331–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/0361073X.2019.1627493

Vallejo-Medina, P., Soler, F., Mayra, G.-L., Alejandro, S.-R., & Laurent, M.-B. (2017). Procedure to validate sexual stimuli: reliability and validity of a set of sexual stimuli in a sample of young colombian heterosexual males. International Journal of Psychological Research, 10(1), 18–24. https://doi.org/10.21500/20112084.2268

van’t Hof, S. R., & Cera, N. (2021). Specific factors and methodological decisions influencing brain responses to sexual stimuli in women. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 131, 164–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.09.013

van Hof, S. R., Van Oudenhove, L., Janssen, E., Klein, S., Reddan, M. C., Kragel, P. A., Stark, R., & Wager, T. D. (2022). The brain activation-based sexual image classifier (BASIC): A sensitive and specific fMRI activity pattern for sexual image processing. Cerebral Cortex, 32(14), 3014–3030. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhab397

Verhavert, S., Wagemans, J., & Augustin, M. D. (2018). Beauty in the blink of an eye: The time course of aesthetic experiences. British Journal of Psychology, 109, 63–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12258

Verschuere, B., Crombez, G., & Koster, E. (2001). The international affective picture system. Psychologica Belgica, 41, 205–217.

Vila, J., Sánchez, M. B., Ramírez, I., Fernández, M. C., Cobos, M. P., Rodríguez, S., Muñoz, M. Á., Tormo, M. P., Herrero, M., Segarra, P., Pastor, M. C., Montañes, S., Poy, R., Moltó, J. (2001). El Sistema Internacional de Imágenes Afectivas (IAPS): Adaptación Española. Segunda parte. Revista de psicología general y aplicada: Revista de la Federación Española de Asociaciones de Psicología, 54(4), 635–657.

Villani, D., & Riva, G. (2012). Does interactive media enhance the management of stress? Suggestions from a controlled study. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 15(1), 24–30. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2011.0141

Waismann, R., Fenwick, P. B. C., Wilson, G. D., Hewett, T. D., & Lumsden, J. (2003). EEG responses to visual erotic stimuli in men with normal and paraphilic interests. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 32, 135–144. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022448308791

Wierzba, M., Riegel, M., Pucz, A., Leśniewska, Z., Dragan, W. Ł, Gola, M., Jednoróg, K., & Marchewka, A. (2015). Erotic subset for the Nencki Affective Picture System (NAPS ERO): Cross-sexual comparison study. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01336

Willenbockel, V., Sadr, J., Fiset, D., Horne, G. O., Gosselin, F., & Tanaka, J. W. (2010). Controlling low-level image properties: The SHINE toolbox. Behavior Research Methods, 42, 671–684. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.42.3.671

Ziogas, A., Habermeyer, E., Santtila, P., Poeppl, T. B., & Mokros, A. (2020). Neuroelectric correlates of human sexuality: A review and meta-analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-01547-3

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. Funding for open access charge: Universitat Jaume I.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Prantner, S., Giménez-García, C., Espino-Payá, A. et al. Representation Gap in Standardized Affective Stimuli Sets: A Systematic Literature Review of Visual Sexual Stimuli. Sexuality & Culture (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-024-10217-z

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-024-10217-z