Abstract

This study investigates people’s associations between the exchange of sexual services for payment and different sexual activities. Sex work entails a range of activities, from in person services to online performances. To date, no study has asked about the activities individuals associate with the exchange of sexual services for payment. The relationship between the exchange of sexual services for payment and specific activities is an important area for inquiry, as there exists considerable variance in people’s views on sex work and associations are impacted by a range of attitudes. Using an original survey involving a substantial sample size of adults in the U.S. (n = 1,034), respondents are asked their level of association between the exchange of sexual services for payment and seven activities: pornographic photos, pornographic videos, webcamming, erotic dancing, erotic massages, oral sex, and sexual intercourse. The results reveal that respondents are more likely to associate the exchange of sexual services for payment with activities requiring in person and physical contact between sex workers and clients than non-physical activities. In addition, we find that conservatives are more likely to associate the exchange of sexual services for payment with non-physical activities than liberals. Moreover, we find that people who view the exchange of sexual services for payment as acceptable are more likely to recognize a broader range of activities as associated with such exchanges than are those who hold more negative attitudes. Views on acceptability are more important than are previous experiences of paying for sexual services. Our findings offer valuable insights for policymakers, researchers, and advocates seeking a comprehensive grasp of the complexities surrounding sex work in contemporary society.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Historically, sex workers have depended on physical venues for making their earnings, including, bars, brothels, clubs, hotels, parlors, parks, saunas, saloons, streets, theaters, and various lodgings—the access to which have differed depending on time, place, laws, and policies, as well as sex workers’ class, gender, race, networks and socio-economic status (Brennan, 2004; Ditmore, 2011; Tsang, 2017, 2019; Yu et al., 2018). Meanwhile, important technological developments have been used by sex workers and other actors profiting from their labor to promote and provide services, including the printed press, the telephone, and the photo and video camera. In modern society, the internet quickly became a place for the sex industry to proliferate and thrive, resulting in an easier and more direct way to produce and distribute sex work related content and services (Agustín, 2007; Brennan, 2004; Brents & Hausbeck, 2007; Jones, 2020; Sanders et al., 2018). These technologies have facilitated the contact between sex workers and their clients. Arguably, they have also broadened the very definition of sex work, which nowadays encompasses activities from the in person full-service, to striptease, pornographic photos and films, phone sex, webcamming, and other forms of online erotic performances (Abel, 2023; Jones, 2020; Rand, 2019; Sanders et al., 2018). In the context of today's rapidly evolving sex industry and its potential impacts on legal and social dimensions, understanding public perceptions of sex work is vital.

Indeed, the company Pornhub, launched in 2007, boasts that they achieve over 125 million daily visits to their network of websites, maintain over 20 million registered users, and have over 100 billion pornographic video views a year (Pornhub, 2022). In 2019, the company reported to have over 98,000 verified amateur sexual content producers on their main website (Pornhub, 2019), a number that has undoubtably increased since. Similarly, the newer company OnlyFans, launched in 2016, has over 100 million registered users and over 1.9 million content creators worldwide (OnlyFans, 2022). The website is a subscription-based platform for content creators to monetize their content and maintain an easily accessible fanbase, with many creators posting sexual content. During the recent COVID-19 pandemic, people turned to OnlyFans and other erotic photo and video services to ameliorate the financial challenges they faced, including individuals with and without previous sex work experience (Nelson et al.2020; Rubattu et al., 2023). Besides digital media content creation, there has also been the arrival and buildup in the number of websites where sex workers advertise meetups for physical services (e.g., Backpage). In sum, contemporary advances in technology have led to an expansion of the types of activities that encompass the sweeping concept of the “sex industry/trade” and the notion of “exchanging sexual services for payment.” This study represents a crucial step in exploring the intricate associations people have with the exchange of sexual services for payment and different activities.

Public perceptions play a crucial role in shaping legal, social, and policy responses to sex work, yet members of the public often have skewed ideas of stigmatized activities like exchanging sexual services for payment. Notably, quantitative academic studies that ask about public attitudes towards the exchange of sexual services for payment do not ask about specific sexual activities. Instead, these studies tend to ask about the acceptability of “prostitution”, “sex work”, “transactional sex”, or “buying” and “selling” sex (Basow & Campanile, 1990; Cosby et al., 1996; Hansen & Johansson, 2022, 2023; Jakobsson & Kotsadam, 2011; Lo & Wei, 2005; May, 1999; Räsaänen & Wilska, 2007; Valor-Segura et al., 2011; Vlase & Grasso, 2021; Yan et al., 2018), which encompass a large variance in activities. A potential issue with this approach is that while one survey respondent might associate the exchange of sexual services for payment with an activity like webcamming, another respondent might associate the concept solely with physical activities, such as sexual intercourse. Hansen and Johansson (2023) find that respondents’ views on the exchange of sexual services for payment are dependent on the concepts that are utilized in survey questions (“prostitution” vs. “sex work”) due to respondents’ different associations with the concepts. Therefore, in this study we specifically explore the extent to which individuals associate the exchange of sexual services for payment with different sexual activities.

Overall, our analysis explores two complementary research questions. What level of associations do individuals have with the exchange of sexual services for payment and different sexual activities? Which socio-demographic and attitudinal variables predict variance in the levels of these associations? To answer these questions, we utilize an original survey of 1,034 respondents. Each respondent was asked their level of association with the exchange of sexual services for payment and seven activities. The activities include pornographic photos, pornographic videos, webcamming, erotic dancing, erotic massages, oral sex, and sexual intercourse. The choice of activities is based on the literature describing sex work types and modern forms of sex work (Abel, 2023; Harcourt & Donovan, 2005; Jones, 2016, 2020; Nelson et al., 2020; Rand, 2019; Rubattu et al., 2023; Sanders et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2018).

Through our exploratory analysis, we uncover four main findings. First, there are greater associations between the exchange of sexual services for payment and activities that involve in person and physical contact between a sex worker and client. Second, our research indicates that conservative individuals tend to associate the exchange of sexual services for payment with a broader range of activities compared to their liberal counterparts. Third, prior experiences of paying for sexual services does not play a central role in predicting levels of associations. Finally, views on the acceptability of the exchange of sexual services for payment lead to a greater recognition of the number of activities associated with these exchanges. Views on acceptability are more important than are previous experiences of paying for sexual services. These results offer valuable insights into the complex interplay between societal attitudes, ideology, personal experiences, and perceptions surrounding sex work.

The findings have important implications for public opinion research, empirical research on attitudes towards sex work, and broader societal issues. If scholars, sex workers’ rights organizations, and policy practitioners utilize broad, all-encompassing concepts to represent the sex industry/trade their audiences may not always associate these concepts with similar types of activities. For researchers, survey responses may contain a low degree of item validity—conflicting interpretations and understandings of the item among the survey respondents, which leads to a greater amount of statistical error in empirical models and results that do not fully and accurately reflect the relationship between variables. For sex workers’ rights organizations, these groups may need to provide a more nuanced discussion of the specific types of sex work and policies they are advocating on behalf of sex workers to the public. Finally, for policy practitioners, policy and/or laws could be unclear to the general populace or ambiguous to participants in the sex industry, which could lead to a myriad of legal issues.

Evolving Perspectives: A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Sex Work

Which activities constitute the exchange of sexual services for payment depend on context, perspective, and time, as well as the concepts that are being used (Ditmore, 2011; Hansen & Johansson, 2023; Lister, 2021). Nowadays, “sex work” is becoming an increasingly common term for describing the activities of individuals who generate revenue by performing erotic services in different ways. Overall, the literature describes sex work as a more encompassing and neutral term than “prostitution” (Hansen & Johansson, 2023; Harcourt & Donovan, 2005; Jones, 2016, 2020; Sanders et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2018). Sex work refers to a range of in person and remote activities, from sexual intercourse, oral and manual stimulation, to erotic massages, striptease, webcamming, and other Internet-based services (Harcourt & Donovan, 2005; Jones, 2020; Sanders et al., 2018: Yu et al., 2018). Generally, prostitution does not describe the latter. Scholars are, in fact, advising against using prostitution because of its narrower meaning and negative connotations (Hansen & Johansson, 2023; McMillan et al., 2018).

Historically, the prostitution framework has generally been used in a gendered and stigmatizing manner to condemn, control, and marginalize women who have sexual relations with men in exchange for payment (Scoular, 2015; Agustín, 2007). Whereas the term sex work positions the exchange of sexual services for payment “as a matter of labor and not culture or morality” (McMillan et al., 2018: 1518), the prostitution term has been deployed as an identity category to distinguish between reputable and disreputable women (Lister, 2021; O’Neill, 2001; Shaver, 2005; Svanström, 2000). Where female sex workers have often been assigned stigmatizing labels like “prostitutes”, “harlots”, and “whores”, male sex workers have been given names like “hustlers” and “mollies” (Lister, 2021; Shaver, 2005). At certain points in history, women who did not adhere to the moral standards of the time risked being labelled as prostitutes, not necessarily for selling sexual services but because of other behaviors, including being on the street late at night and wearing attention-grabbing clothes (Svanström, 2000).

The prostitution framework is still deployed by governments and groups who disapprove of those who engage in paid sexual relations and advocate for repressive policies (Östergren, 2018, 2020). Such measures often center around the activities that have traditionally been recognized as prostitution and involve direct genital contact (Harcourt & Donovan, 2005; Lister, 2021; Östergren, 2018, 2020). Harcourt and Donovan’s (2005) comprehensive sex work typology identifies twenty-five types of sex work based on the distinction between direct and indirect genital contact with clients. The direct group includes sex workers who meet clients in places like bars, brothels, clubs, homes, hotels, and on the streets to engage in sexual intercourse or perform oral sex and hand jobs. This group contains activities that have commonly been recognized as prostitution. The indirect group includes individuals and activities that are less likely to be seen as prostitution, for instance, beachboys, bondage and discipline, geishas, gigolos, lap dancing, and massages. People in this latter group are less likely to think of themselves as sex workers, according to the authors. The same may apply to those who perform indirect sex work activities like webcamming and pornographic photos and videos, which have become more common since Harcourt and Donovan’s (2005) study was published.

Digital technologies play an important role in contemporary sex work, as they have enabled easier access to content and services related to sex work, concurrently showcasing the diversity of sex work. Sex workers use these technologies in a variety of ways; for advertisement, communication with clients, peer-support, community-building, and political organizing, but also for webcamming and other online erotic performances (such as the exchange of pornographic photo and video material for payment) (Abel, 2023; Jones, 2016, 2020; Rand, 2019; Sanders et al., 2018). Some combine in person services with online work while others only provide services online. Arguably, digitalization has broadened the very definition of sex work. Still, which activities people associate with the exchange of sexual services for payment remains largely unknown.

Sex work typologies that outline distinct working modes and venues are useful for understanding the wide range of sex work. However, it is important to note that the lived experiences of people who exchange sexual services for payment are complex. For instance, Yu, McCarty, and Jones (2018) identified high levels of mobility among Chinese female sex workers in the city of Haikou. Their engagement in sex work spanned across different sex work categories in terms of where and how they worked. We also know that many sex workers engage with clients in ways that are not only of the sexual nature, but social and emotional (Brennan, 2004; Cabezas, 2004; Yu et al., 2018). That said, sex workers’ flexibility and their client interactions can be heavily restricted by factors like socio-economic and migratory status (de Jesus Moura et al., 2022). Digital platforms often exert control over labor practices, limiting agency (Abel, 2023; Jones, 2016, 2020; Rand, 2019; Sanders et al., 2018). Given the diversity of what sex workers do, it is important to inquire about people’s associations with the exchange of sexual services for payment. Furthering our understanding of individual associations with different sexual activities is a sensible starting point.

Attitudes Towards Sex Work

There have only been a handful of studies that explore public attitudes towards sex work and none of these studies specifically investigate associations between the exchange of sexual services for payment and specific activities. That said, the literature that explores the acceptability of exchanging sexual services for payment uncovers several important trends and debates. Thus, it is useful to extrapolate from these previous studies to provide some direction regarding associations with activities. It is also important to investigate whether the tangentially related findings of previous research hold up in today’s reality where the activities contained under the umbrella term that is the exchange of sexual services for payment have expanded into new mediums and avenues. Therefore, we quickly summarize the key findings here.

In terms of socio-demographic trends, studies from the United States (U.S.), Sweden, and Denmark find mixed support regarding age impacting views on the exchange of sexual services (Cosby et al., 1996; May, 1999; Hansen & Johansson, 2022, 2023; Powers et al., 2023). However, we might expect that older respondents are more likely to associate the exchange of sexual services for payment with physical activities traditionally understood as “prostitution” (Harcourt & Donovan, 2005). Regarding education, studies from the U.S. and Sweden find that it correlates positively with support for the trade in sexual services (Jakobsson & Kotsadam, 2011; May, 1999). One study on the Danish population finds a negative relationship between education and acceptability (Hansen & Johansson, 2022). One relationship that is clear from these studies is that a higher educational attainment is related to a greater awareness of debates and discussion surrounding the exchange of sexual services for payment. One firm socio-demographic finding in the literature is that women are more likely than men to have negative views on the exchange of sexual services for payment (Cosby et al., 1996; Cotton et al., 2002; Hansen & Johansson, 2022; May, 1999). Thus, it may be reasonable to expect that women are more likely to recognize the exchange of sexual services for payment as encompassing a broader range of activities. Alternatively, it could be the case that women think primarily of street-based sex work and other low status, more stigmatized sex work activities.

Research shows a range of attitudes correlated with positive views on exchanging sexual services for payment. Studies confirm that a liberal ideology broadly, as well as specific liberal attitudes, translate into more positive evaluations of sex work (Cosby et al., 1996; Peracca et al., 1998; May, 1999; Valor-Segura et al., 2011; Hansen & Johansson, 2022, 2023; Powers et al., 2023). For instance, Valor-Segura et al. (2011) uncover that a greater commitment to liberal attitudes towards gender equality is related to positive views on prostitution in the Spanish context. Related, Hansen and Johansson (2022, 2023) find that a liberal placement on a left–right self-placement ideological scale is associated with more liberal attitudes towards sexual behavior in general in Denmark and the U.S. The authors confirm a correlation between liberal self-placement and a belief that activities such as non-committal causal sex and exchanging sexual services for payment are acceptable. Thus, liberals may be less likely to assign stigma to activities for solely being recognized as associated with the sex industry due to their more permissive attitudes towards sex in general.

Similar to political ideology, one would expect partisans to take divergent paths when assessing the association between particular activities and the trade in sexual services. The role of partisanship in the U.S. in predicting a range of attitudes and behaviors has increased in importance, from support for the #MeToo movement (Hansen & Dolan, 2022) to views on exchanging sexual services for payment (Hansen & Johansson, 2023). Republican partisans are more likely to invoke religious arguments when assessing behaviors that they deem as related to morality and sexual policy (Kreitzer, 2015; Lynderd, 2014). For example, Gaines and Garand (2010) find that moral and religious attitudes are key to explaining variance in predicting attitudes, such as Republican opposition to gay marriage. Thus, we would expect that Republican partisans are more likely to indicate that behaviors they deem as morally questionable and “deviant”, or sexual activities that are far removed from procreational purposes, as being associated with the sex industry.

Finally, while no study has specifically investigated which sexual activities individuals associate with the exchange of sexual services for payment and general acceptability of the sex industry, we have some expectations regarding findings. Hansen and Johansson (2022) show that tolerant views towards sexual behavior are related to greater acceptability of the trade in sexual services. In particular, the authors find that the view that engaging in non-committal casual sex is acceptable behavior is strongly linked to more tolerant views towards prostitution. The finding demonstrates that liberal attitudes towards sexual behavior are linked to one another. Here, we expect that positive views towards the sex industry in general will result in a broader range of activities being associated with exchanging sexual services for payment. In particular, the argument is that individuals will be more likely to associate the exchange of sexual services for payment with new digital technologies due to their more liberal stance towards such exchanges.

Hypotheses

\({H}_{1}\): There exists a greater association with the exchange of sexual services for payment and sexual activities that involve in person and physical contact between a potential provider and purchaser than activities that do not entail in person and physical contact.

\({H}_{2}\): Attitudes towards the acceptability of exchanging sexual services for payment will mitigate the impact any prior purchase experience has on the degree of associations.

\({H}_{3}\): Conservative respondents will have a greater level of association between the exchange of sexual services for payment and the activities than do liberal respondents.

\({H}_{4}\): Respondents with more permissive views on exchanging sexual services for payment will have a greater association between such exchanges and the activities.

Method

The data used in this study stems from an original survey that asks respondents their level of association between the exchange of sexual services for payment and several activities. The survey was carried out on a panel of residents of the U.S. using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) on April 7, 2022. Adults aged 18 and older residing in the U.S. were allowed to take the survey. Informed consent was required. Respondents were paid $1 for their participation, even if they did not answer all the questions. The average amount of time it took for respondents to complete the survey was 6 minutes and 15 seconds. Thus, if calculating an hourly wage rate, the respondents were compensated more than the U.S. national minimum wage. In total, there were 1,093 participants that started the survey. When accounting for non-responses on some of the control variables, the full multiple regression models contain between 1,028 and 1,034 respondents. A sample size of > 1,000 was chosen so that the sample size would be more than sufficient for an empirical analysis and statistical model convergence.

Overall, the sample contains slightly more men and Democratic partisans than does the population of the U.S. However, the sample mirrors the population for all other variables utilized in the analysis. Studies show that MTurk can be a useful and reliable data source so long as researchers are aware of how the sample differs from the population, they utilize survey weights to account for incongruence between the sample and population, and reflect on how differences may affect their result (Buhrmester et al., 2011; Kennedy et al., 2020; Levay et al., 2016). Therefore, we estimate and apply post-stratification survey weights in all our analyses to reduce sampling error. Descriptive statistics are reported in Appendix A.

Dependent Variables

The dependent variables of interest in this study include seven sexual activities that could be performed as services in exchange for payment: pornographic photos, pornographic videos, webcamming, erotic dancing, erotic massages, oral sex, and sexual intercourse. For each activity, respondents were asked, “How closely do you associate the exchange of sexual services for payment with the following?” The respondents were offered a 10-point Likert-scale from “0 = not at all” to “10 = to a great degree” where they could place their level of association. A choice of five on the scale indicates a neutral level of association. The use of the word “association” in the survey question represents the definitional feature of “a mental connection between ideas” (Oxford Dictionary, 2023). Prior to launching the survey, we conducted a trial survey to determine whether variance in associations exists and if the word association was understood by respondents. Since the Likert-scale is treated as a continuous measure, we utilize OLS linear regression with post-stratification survey weights to predict levels of association. We should note that we ask about the “exchange of sexual services for payment” instead of concepts such as “prostitution” or “sex work” due to the finding in Hansen and Johansson (2023) showing that use of these concepts impacts responses in a myriad of different and important ways. Thus, we aim to describe the activity of interest more explicitly in the question.

In Table 1, the mean level of association with the exchange of sexual services for payment and standard deviation is presented for the seven activities. The first aspect of Table 1 to highlight is that the mean level of association is larger for those activities that involve the sex worker and client engaging in physical or in person interaction (i.e., erotic dancing, erotic massages, oral sex, and sexual intercourse). Conversely, the mean is lowest for those activities where physical or in person interaction does not occur between the provider and purchaser (i.e., pornographic photos, pornographic videos, and webcamming). The activity with the lowest level of association was pornographic photos, while the activity with the highest level of association was sexual intercourse. The descriptive statistics and bivariate analyses indicate support for \({H}_{1}\). For each of the seven activities, the mean level of association leans more towards association rather than the neutral position. A second aspect of Table 1 to notice is that the standard deviation values indicate substantial variance in respondents’ levels of associations.

Figure 1 displays the response distribution densities for each of the seven activities. Each of the seven distributions are left skewed, which indicates that the mean is slightly smaller than is the median and modal responses. In other words, a larger proportion of respondents associate the activities with the exchange of sexual services for payment than does the proportion that does not. Across the seven activities less than 15 percent of respondents selected any one singular category of association, which demonstrates a large variance in response selections. On average, around one-third of respondents (31.36 percent) indicate a lack of association between the activities and the exchange of sexual services for payment – selecting responses 0–4. One in 10 respondents (10.04 percent) selected the neutral category of association across the seven activities. Conversely, on average just over a majority of respondents (58.6 percent) selected some level of association between the seven activities and the exchange of sexual services for payment—selecting responses 6–10. The descriptive statistics and density plots convincingly demonstrate that there is a large amount of variance left to explain in levels of associations.

Independent Variables

There are several variables included in the multiple regression analyses as predictor and control variables. First, several socio-demographic variables are utilized in the regression models, which include age, gender, race, education, and income. Second, we include a few attitudinal variables as predictors of levels of associations. Since the U.S. population is increasingly sorted based on partisan affiliation in regard to a range of attitudes, political partisanship is included as a predictor variable. Likewise, political ideology is utilized as an independent variable because we expect conservative respondents to be more likely to identify certain activities as being associated with the exchange of sexual services for payment. In addition, views on the acceptability of the exchange of sexual services for payment is included as a predictor variable. The expectation is that individuals who view sex work as an acceptable profession will be more likely to recognize and associate a range of activities with the exchange of sexual services for payment. Finally, we include a variable that accounts for previous engagement with the exchange of sexual services for payment. In particular, the regression models control for whether a respondent had previously paid for sexual services. All descriptive statistics and variable coding for these variables are presented in Appendix A.

Results

Regression output from the models predicting the level of association between the exchange of sexual services for payment and the seven sexual activities is presented in Table 2. First, there are several socio-demographic trends that are statistically significant in the regression output, but substantively unimportant when estimating effects.Footnote 1 Age is a statistically significant predictor of association with activities that have been more traditionally linked with the exchange of sexual services for payment—pornographic photos, oral sex, and sexual intercourse. However, when holding all other independent variables at their survey-weighted mean values and calculating predictions, the substantive effect of age is nonexistent. The 95 percent confidence bounds around the point estimate overlap at every age value, which means that we cannot rule out that the predicted levels of associations are the same at every age (see, Appendix B, Figure 4). The regression output result is likely being driven by only a few respondents over the age of 70 years old. A similar interpretation occurs when exploring the impact of gender. While women appear to be statistically more likely than men in several instances to associate the exchange of sexual services for payment with an activity, the substantive effects are absent when plotting the effects holding all other variables at their survey-weighted mean values (see, Appendix B, Figure 5). Again, the 95 confidence bounds around the point estimate overlap for women and men, which indicates that their predicted levels of associations are not statistically different. Similarly, respondent race has no substantive impact on associations despite being statistically significant in one model – overlapping predictions.

Respondent education and income levels have very small substantive effects on level of associations. On average, when comparing a respondent at the lowest education level with a respondent at the highest education level, there is either no substantive difference (pornographic videos and photos) or a small difference of less than one-tenth to one-half of a point on the 10-point scale (Appendix B, Figure 6). The effect is slightly larger for income (Appendix B, Figure 7). On average, when comparing a respondent at the lowest income bracket to a respondent at the highest income bracket, the average difference in the levels of association is less than a quarter of a point across the seven associations. Again, there are very few respondents at extreme values on both variables, which indicates that the effect could be driven by outliers.

One of the attitudinal and one of the behavioral variables included in the models are also weak predictors of levels of associations between the exchange of sexual services for payment and the seven activities. First, political partisanship has only a very small substantive relationship with levels of association in instances where it is statistically significant. In four instances, Republican partisans have a substantively higher level of association between the exchange of sexual services for payment and the activities when holding all other variables at their survey-weighted means—pornographic photos, webcamming, erotic messages, and sexual intercourse. That being said, the substantive difference between Democratic and Republican partisans was on average less than one-tenth of a point on the 10-point scale in levels of association. The difference accounts for less than one percent in the variance of the scale.

Second, prior experience of paying for sexual services is only associated with an increase in association between the exchange of sexual services for payment and two out of seven activities. Respondents that have indicated prior experience paying for sexual services are around a half a point more likely to associate pornographic photos and sexual intercourse with the exchange of sexual services for payment. Given that these two activities represent the most common non-physical and physical activities associated with the exchange of sexual services for payment, the result is intuitive. We should note that when estimating models that do not control for attitudes towards the acceptability of the exchange of sexual services for payment, prior experience of paying for sex is a statistically significant and substantively useful predictor for all seven activities (see, Appendix C, Table 5). The effect of the variable is quite large from just over half a point difference to over a full point difference when comparing a respondent with prior experience to one with no prior experience. However, when controlling for acceptability in the models in Table 2, prior experience is not a useful predictor. The result indicates that attitudes towards the exchange of sexual services for payment are more important than prior personal experiences with paying for sex. The result is salient as the correlation between views on the acceptability of the exchange of sexual services for payment and prior experience with paying for sex is very weakly correlated at 0.181. The finding provides support for \({H}_{2}\).

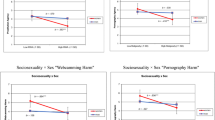

Two attitudinal variables included in the models perform better when predicting levels of associations between the exchange of sexual services for payment and the seven activities. First, political ideology is a statistically significant predictor of levels of association with the exchange of sexual services for payment for five out of seven activities. In Fig. 2, we plot the substantive effect of the political ideology variable on levels of associations while holding all other variables at their survey-weighted mean values. When comparing a very liberal respondent to a very conservative respondent, the very conservative respondent has around half a point greater association between the exchange of sexual services for payment and pornographic photos, pornographic videos, and oral sex. Comparing the same respondents, very conservative respondents are slightly more likely to associate the exchange of sexual services for payment with erotic dancing and sexual intercourse. The results indicates that conservatives are more likely to associate the exchange of sexual services for payment with those activities that conservative groups consistently target as immoral sexual behavior (i.e., pornography, stripping, and non-procreative sex acts). The findings provide support for \({H}_{3}\).

The attitudinal variable with the largest substantive impact on levels of association between the exchange of sexual services for payment and the seven activities is views on acceptability. The effect of the attitudinal variable is graphically displayed in Fig. 3. Across all seven models, individuals who indicate that the exchange of sexual services for payment is “to a great degree” acceptable are substantially more likely than individuals who responded “not at all” acceptable to associate the activities with exchanging sexual services for payment. In fact, the average predicted level of association for each of the seven activities for an individual who indicates the exchange of sexual services for payment is “not at all” acceptable is between 2.5 and 4.4 when accounting for 95 percent confidence bounds. Thus, even when factoring in the upper 95 percent confidence limit, the predicted level of association for these individuals leans towards not associating the exchange of sexual services for payment with the activity. On the other hand, the predicted level of association across the seven activities for an individual who indicated that the exchange of sexual services for payment is “to a great degree” acceptable was between 6.6 and 8.2 when accounting for 95 percent confidence bounds. The results indicates that for these respondents there is a strong association between the exchange of sexual services for payment and each of the seven activities. The substantive takeaway is that individuals with a more favorable view of exchanging sexual services for payment will have a greater awareness of the range of associated activities. The findings provide evidence for \({H}_{4}\).

Discussion

This study explored people’s association between the exchange of sexual services for payment and different sexual activities. Using an original online survey, we asked 1,000 + respondents their levels of associations with the exchange of sexual services for payment and seven activities—pornographic photos, pornographic videos, webcamming, erotic dancing, erotic massages, oral sex, and sexual intercourse. In general, the results demonstrate that there is wide variance in terms of what activities individuals view as encompassing the broader notion of exchanging sexual services for payment.

The results point to four main findings. First, there is a greater association between the exchange of sexual services for payment and activities that involve in person and physical contact between a sex worker and client than with activities involving digital media. Second, conservative respondents have a broader conceptualization of the exchange of sexual services for payment and are more inclined to associate it with non-physical activities than are liberal respondents. Third, experiences of having paid for sexual services play only a limited role in predicting levels of associations. Views on acceptability are more important than is prior experience with paying for sexual services. Lastly, views on the acceptability of exchanging sexual services for payment was related to higher associations with each of the activities.

The reason as to why individuals more readily associate the exchange of sexual services for payment with in person and physical activities may be explained by the fact that, historically, sex work has generally hinged on personal interactions and experiences. In contrast, digital media mediated sex work activities, such as webcamming, are newer and may be perceived as more detached from direct interaction and the person providing the service, leading to weaker associations. This reasoning aligns with previous studies that have emphasized the significance of embodied labor and personal relationships in understanding sex work dynamics. Conservatives' broader conceptualization of the exchange of sexual services for payment may be linked to their moral and ethical perspectives. Activities such as erotic massage or webcamming might be considered morally questionable or "deviant" from a conservative perspective. Consequently, conservatives may extend the definition of exchanging sexual services for payment to encompass a wider array of activities. This finding aligns with prior research demonstrating how conservative ideologies tend to take a stricter stance on sexual morality and view various sexual behaviors through a more critical lens. The finding that views on acceptability are more important than is prior experience with paying for sexual services resonates with earlier studies that have highlighted the multifaceted nature of attitudes towards sex work. People's views on sex work are influenced by a myriad of factors. Social and cultural factors such as norms, education, and socialization likely play more significant roles in influencing these associations than people's personal experiences with paying for sexual services. Acceptability serves as a lens through which people interpret and categorize various behaviors, meaning individuals who view the exchange of sexual services for payment as more acceptable are more open to recognizing a broader range of activities as part of such exchanges.

The results have important implications for attempts to broadly measure support for exchanging sexual services for payment. If individuals associate the exchange of sexual services for payment with different activities to drastically differing degrees, variance in views on exchanging sexual services for payment might be partially a function of these associations rather than empirical realities. Since we find here that individuals are more likely to associate such exchanges with in person and physical contact activities, scholars need to be cognizant that asking about the exchange of sexual services for payment broadly is going to lead individuals to reflect mostly on in person and physical types of activities. Today, a large share of sex work takes place in online spaces using digital technologies. Our finding indicates that individuals are less likely to reflect on these activities that encompass the preponderance of sex work today, which means that broad measures only capture views on a minority of activities contained within the sex industry.

In addition, the results have implications for policy. Groups who advocate for policy changes pertaining to the exchange of sexual services for payment need to be cognizant of the attitudes and associations of the public, as to not cause misunderstandings between public opinion and the measures they promote. The stronger association between the exchange of sexual services for payment and those activities that involve in person and physical contact calls for a nuanced and context-aware approach to sex work policies. Policymakers should consider these associations when crafting regulations and support systems for sex workers. The observed differences in perceptions between conservatives and liberals highlight the need for policies that acknowledge diverse views on sex work. The lack of a significant link between prior experiences of paying for sexual services and associations with specific activities suggests that policy efforts focused solely on regulating clients may have limited impact. Instead, policymakers should consider a broader approach that addresses the different working conditions and ensures the rights of sex workers themselves. The central role of acceptability in shaping perceptions highlights the need for policies that prioritize awareness and education campaigns to promote informed and open discussions surrounding the exchange of sexual services for payment. These findings emphasize that any effective policy framework must be sensitive to the multifaceted nature of public perceptions and attitudes toward sex work.

The present study was limited to asking about the association between the exchange of sexual services for payment and seven sexual activities (pornographic photos, pornographic videos, webcamming, erotic dancing, erotic massages, oral sex, and sexual intercourse). A better understanding of the activities people associate with the exchange of sexual services for payment can contributes to sex work theorizing. Future studies should look at people’s associations with other concepts and activities, including sex work activities that are not only erotic in nature. In addition, a useful avenue for future research would be to explore whether the physical space in which the sex work activity occurs impacts people’s views, as well as the level of association with different activities.

Beyond studies on the exchange of sexual services for payment, the findings here could be extended to similar research exploring attitudes on bodily autonomy, especially where morality is a consideration. For instance, one area for future research would be to explore how associations and framing impacts views on abortion. There is no doubt that the word abortion is associated to varying degrees with different types of activities among individuals. Thus, support for abortion is undoubtable partially a product of these associations. Similarly, word choice might elicit different types of associations (pro-choice vs. women’s reproductive health vs. right to choose). Applying the results here, this would be an important area of inquiry for future research.

Data Availability

De-identified data will be made available through a data repository.

Code Availability

R Statistical Software code and packages will also be made available in the data repository.

Notes

The coefficients for these variables are statistically significant in several instances; however, when plotting the variables’ relationships with the associations the results indicate that their impact is negligible. A coefficient is an integer that is multiplied by the value of the variable that is independent of all other predictor variables. To view the substantive relationship between a predictor variable and the dependent variable, a researcher should calculate predictions with confidence bounds while accounting for the other variables. Therefore, we have calculated and plotted predictions for all the predictor variables.

References

Abel, G. (2023). “You’re selling a brand”: Marketing commercial sex online. Sexualities, 26(3), 354–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/13634607211056189

Agustín, L. M. (2007). Questioning solidarity: Outreach with migrants who sell sex. Sexualities, 10(4), 519–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460707080992

Basow, S. A., & Campanile, F. (1990). Attitudes toward prostitution as a function of attitudes toward feminism in college students: An exploratory study. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 14(1), 135–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1990.tb00009.x

Brennan, D. (2004). What’s love got to do with it? Transnational desires and sex tourism in the Dominican Republic. Duke University Press.

Brents, B. G., & Hausbeck, K. (2007). Marketing sex: US legal brothels and late capitalist consumption. Sexualities, 10(4), 425–439. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460707080976

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., & Gosling, S. (2011). Amazon’s mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(1), 3–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610393980

Cabezas, A. L. (2004). Between love and money: Sex, tourism, and citizenship in cuba and the dominican republic. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 29(4), 987–1015. https://doi.org/10.1086/382627

Cosby, A. G., May, D. C., Frese, W., & Dunaway, R. G. (1996). Legalization of crimes against the moral order: Results from the 1995 United States survey of gaming and gambling. Deviant Behavior: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 17, 369–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.1996.9968036

Cotton, A., Farley, M., & Baron, R. (2002). Attitudes toward prostitution and acceptance of rape myths. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(9), 1790–1796. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00259.x

de Jesus Moura, J., Pinto, M., Oliveira, A., Andrade, M., Vitorino, S., Oliveira, S., Matos, R., & Maria, M. (2022). Sex workers’ peer support during the COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons learned from a study of a Portuguese community-led response. Critical Social Policy. https://doi.org/10.1177/02610183221119955

Ditmore, M. H. (2011). Prostitution and sex work. Greenwood.

Gaines, N. S., & Garand, J. C. (2010). Morality, equality, or locality: analyzing the determinants of support for same sex-marriage. Political Research Quarterly, 63(3), 553–567.

Hansen, M. A., & Dolan, K. (2022). Cross-pressures on political attitudes: Gender, party, and the #MeToo movement in the United States. Political Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09763-1

Hansen, M. A., & Johansson, I. (2022). Predicting attitudes towards transactional sex: The interactive relationship between gender and attitudes on sexual behavior. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 19(1), 91–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-020-00527-w

Hansen, M. A., & Johansson, I. (2023). Asking about “prostitution”, “sex work” and “transactional sex”: Question wording and attitudes towards trading sexual services. The Journal of Sex Research, 60(1), 153–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2022.2130859

Harcourt, C., & Donovan, B. (2005). The many faces of sex work. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 8, 201–206. https://doi.org/10.1136/sti.2004.012468

Jakobsson, N., & Kotsadam, J. (2011). Gender equity and prostitution: An investigation of attitudes in Norway and Sweden. Feminist Economics, 17(1), 31–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2010.541863

Jones, A. (2016). “I get paid to have orgasms”: Adult webcam models’ negotiations of pleasure and danger. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 42(1), 227–256.

Jones, A. (2020). Camming: Money, power, and pleasure in the sex work industry. NYU Press.

Kennedy, R., Clifford, S., Burleigh, T., Waggoner, P., Jewell, R., & Winter, N. (2020). The shape of and solutions to the MTurk quality crisis. Political Science Research and Methods, 8(4), 614–629. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2020.6

Kreitzer, R. J. (2015). Politics and morality in state abortion policy. State Politics and Policy Quarterly, 15(1), 41–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532440014561868

Levay, K., Freese, J., & Druckman, J. (2016). The demographic and political composition of mechanical turk samples. SAGE Open. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016636433

Lister, K. (2021). Harlots, whores & hackabouts. A history of sex for sale. Thames & Hudson.

Lo, V.-h, & Wei, R. (2005). Perceptual differences in assessing the harm of patronizing adult entertainment clubs. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 18(4), 475–487. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edh107

Lynderd, B. T. (2014). Republican theology: The civil religion of american evangelicals. Oxford University Press.

May, D. C. (1999). Tolerance of nonconformity and its effect on attitudes toward the legalization of prostitution: A multivariate analysis. Deviant Behavior: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 20, 335–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/016396299266443

McMillan, K., Worth, H., & Rawstorne, P. (2018). Usage of the terms prostitution, sex work, transactional sex, and survival sex: Their utility in HIV prevention research. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(5), 1517–1527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-1140-0

Nelson, A. J., Yu, Y. J., & McBride, B. (2020). Sex work during the COVID-19 pandemic. Exertions. https://doi.org/10.21428/1d6be30e.3c1f26b7

O’Neill, M. (2001). Prostitution & feminism. Towards a politics of feeling. Polity Press.

OnlyFans. (2022). Our team and goals. OnlyFans–statistics. Accessed 12 Oct 2022. https://onlyfans.com/about.html

Östergren, P. (2018). Sweden. In S. Ø. Jahnsen & H. Wagenaar (Eds.), Assessing prostitution policies in Europe (pp. 169–184). Routledge Press.

Östergren, P. (2020). From zero-tolerance to full integration. Rethinking prostitution policies. In Z. Davy, A. C. Santos, C. Bertone, R. Thoreson, & S. E. Wieringa (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of global sexualities (pp. 569–599). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Oxford Dictionary. (2023). Association. Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries. Accessed 1 Feb 2023. https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/association

Peracca, S., Knodel, J., & Saengtienchai, C. (1998). Can prostitutes marry? Thai attitudes toward female sex workers. Social Science & Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00089-6

Pornhub. (2019). The 2019 year in review. Pornhub insights, Accessed 12 Oct 2022. https://www.pornhub.com/insights/2019-year-in-review

Pornhub. (2022). Statistics. Pornhub insights—Press, Accessed 12 Oct 2022. https://www.pornhub.com/press

Powers, R. A., Burckley, J., & Centelles, V. (2023). Sanctioning sex work: Examining generational differences and attitudinal correlates in policy preferences for legalization. The Journal of Sex Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2023.2216201

Rand, H. M. (2019). Challenging the invisibility of sex work in digital labour politics. Feminist Review, 123(1), 40–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141778919879749

Räsaänen, P., & Wilska, T.-A. (2007). Finnish students’ attitudes towards commercialised sex. Journal of Youth Studies, 10(5), 557–575. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260701597243

Rubattu, V., Perdion, A., & Brooks-Gordon, B. (2023). “Cam girls and adult performers are enjoying a boom in business”: The reportage on the pandemic impact on virtual sex work. Social Sciences, 12(2), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12020062

Sanders, T., Scoular, J., Campbell, R., Pitcher, J., & Cunningham, S. (2018). Internet sex work. Palgrave MacMillan.

Scoular, J. (2015). The subject of prostitution: Sex work, law and social theory. Routledge Press.

Shaver, F. M. (2005). Sex work research. Methodological and ethical challenges. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(3), 296–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260504274340

Svanström, Y. (2000). Policing public women. The regulation of prostitution in Stockholm 1812–1880. Atlas Akademi.

Tsang, E. Y. (2017). Neither “bad” nor “dirty”: High-end sex work and intimate relationships in urban China. China Quarterly, 230, 444–463. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741017000649

Tsang, E. Y. (2019). Erotic authenticity: Comparing intimate relationships between high-end bars and low-end bars in China’s global sex industry. Deviant Behavior, 40(4), 461–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2018.1431040

Valor-Segura, I., Expósito, F., & Moya, M. (2011). Attitudes toward prostitution: Is it an ideological issue? The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 3(2), 159–176.

Vlase, L., & Grasso, M. (2021). Support for prostitution legalization in Romania: Individual, household, and socio-cultural determinants. The Journal of Sex Research, Latest Articles. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2021.1968334

Yan, L., Xu, J., & Zhou, Y. (2018). Residents’ attitudes toward prostitution in Macau. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(2), 205–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1338293

Yu, Y. J., McCarty, C., & Jones, J. H. (2018). Flexible labor: The work strategies of female sex workers in post-socialist China. Human Organization, 77(2), 146–156.

Acknowledgements

Authors are listed in reverse order alphabetically. IRB Approval: Granted IRB approval on 3/28/22, IRB# FY20-30.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Kristianstad University. N/A.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors contributed equally.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A: Variable Coding and Descriptive Statistics

Appendix B: Independent Variables—Predictions Plots

Appendix C: Regression Models—Without Acceptability

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Johansson, I., Hansen, M.A. What Sex Workers Do: Associations Between the Exchange of Sexual Services for Payment and Sexual Activities. Sexuality & Culture 28, 825–850 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-023-10148-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-023-10148-1