Abstract

To date, little is known about the psychological functioning of polyamorous individuals about the variables explaining positive attitudes towards polyamory. This study aims to investigate the constructs of attachment, emotion regulation and sexual satisfaction in polyamory. Self-report questionnaires were administered to a sample of adults reporting to be polylovers (n = 76) and to a sample of non-polylovers (n = 102). Polyamorous individuals, compared to controls, scored significantly higher on sexual satisfaction and dysregulation of positive emotions. Moreover, positive attitudes towards polyamory correlated with higher levels of sexual satisfaction. However, this relationship was moderated by the dimension of avoidant attachment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the last two decades, research has focused on Consensually Non-Monogamous (CNM) relationships (Johnson et al., 2015; Haupert et al., 2017). Polyamory, a type of CNM relationship, is “a kind of relationship in which it is possible, valid, and worthwhile to maintain (usually long-term) intimate and sexual relationships with multiple partners simultaneously” (Haritaworn et al., 2006). As pointed out by Mitchell et al. (2014), the few studies on polyamory adopted a sociological perspective without using quantitative methods. Psychological studies focused on two research lines: the first examining the psychological variables predicting a polyamorous status (i.e., being engaged in a polyamorous relationship) and the second examining the attitudes towards polyamory, results suggest that some personality traits are related to being involved in polyamorous relationships, as well to having a positive attitude towards polyamory. Stressing the need to investigate attitudes towards polyamory in polyamorous and monogamous populations. However, our knowledge on the topic is limited. Specifically, some of the main factors associated with romantic relationships such as attachment, sexual satisfaction, and emotion dysregulation, have not been explored yet.

Attachment, Sexual Satisfaction, and Emotion Dysregulation

The attachment theory provides a useful framework to understand adult relationships (Flicker et al., 2021). Representations of self and others, developed during childhood, shape relational beliefs and expectations in adult relationships, including romantic relationships (Bowlby, 1988; Shaver & Mikulincer, 2009). Securely attached individuals are confident in others’ availability, while insecurely attached individuals are not (Moors et al ., 2019). In this paper, we will refer to attachment styles as converging in two dimensions: anxiety and avoidance (Hazan & Shaver, 2017). Adults with avoidant attachment experience discomfort with intimacy and do not accept emotional dependency. Adults with anxious attachment are concerned about the relationship and need interpersonal approval (Shaver & Mikulincer, 2002). The quality of attachment styles is associated with romantic relationship satisfaction (Candel & Turliuc, 2019; Hadden et al., 2014), and sexual satisfaction among CNM individuals (Moors et al., 2019). Generally, avoidant individuals are prone to be more self-reliant and avoid interpersonal closeness, relying more on themselves for sexual satisfaction. Anxious individuals tend to seek active loving reassurances from their partners and use sex to increase their confidence (Davis et al., 2004; Schachner & Shaver, 2004).

Emotion dysregulation is one of the processes implied in the pathways linking attachment quality to several psychological outcomes: (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007 Velotti et al., 2019, 2022). Emotion regulation refers to the ability to modulate the intensity and duration of one’s own emotional state, and to reach one’s goals independently of that emotional state (Gratz & Roemer, 2004). An early secure attachment bond is the optimal context for the development of emotion regulation (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). Several pathological processes, observed in romantic relationships and sexual functioning, are linked to poor emotion regulation (Florean & Păsărelu, 2019; Garofalo et al., 2016; Velotti et al., 2011). The role of the capacity to regulate positive emotions has not been investigated yet, despite its potential relevance in conditions involving hedonic components such as sexuality (Weiss et al., 2019). Dysregulation of positive emotions typically occurs when an individual feels pleasant emotions such as joy, excitement or pride. There are several forms of dysregulation of positive emotions, such as the proneness to act rashly when experiencing positive emotions, the difficulty to maintain a goal while experiencing positive emotions and the proneness to formulate negative judgments of positive emotions, leading to negative emotional states (Weiss et al., 2015a, 2015b).

As briefly illustrated, the attachment theory and its nomological network (i.e., the relevant concepts and their relationships underlying the theory), including emotion dysregulation, appears a proficient perspective from which to investigate romantic relationships. This research field concluded that insecure attachment and emotion dysregulation are connected to dysfunctions in romantic relationships. In contrast, little is known about the role of the dysregulation of positive emotions. Therefore, the explicative value of attachment in the field of romantic relationships suggests the examination of this dimension in polyamory and of the relationship between polyamory attitudes and sexual satisfaction.

Polyamory, Sexual Satisfaction, Attachment, and Emotion Dysregulation

Polylovers report high sexual satisfaction (Conley et al., 2017, 2018; Moors et al., 2017). Wosick-Correa (2010) suggests that these relationships involve open communication of one's sexual desires. From this perspective, positive attitudes towards polyamory might indicate greater sexual assertiveness,which would lead to a better recognition of other's needs and to a better sexual satisfaction (Mark & Lasslo, 2018). Therefore, greater sexual satisfaction may be observed among polyamorous individuals compared to monogamous individuals and may be positively associated with positive attitudes towards polyamory.

As observed in the link between sociosexual behaviors and attitudes towards CNM (Ka et al., 2020), the security of attachment is likely to moderate the relationship between attitudes towards polyamory and sexual satisfaction. Several hypotheses have been tested regarding the attachment profiles of polylovers. On one hand, some authors formulate the hypothesis that positive attitudes towards polyamory and/or being involved in polyamorous relationships should be associated with insecure attachment styles (Ka et al., 2020; Moors et al., 2019). Indeed, polyamory, for anxious individuals, who seek more affection from partners (Ka et al., 2020), would be a strategy to satisfy an excessive need for closeness and to ward off the fear of loneliness. Alternatively, adults with avoidant attachment may use polyamory as a defensive strategy against the fear of intimacy, diluting closeness through multiple concurrent relationships (Moors et al., 2019). However, these hypotheses were not confirmed by the results of the original studies. On the other hand, several authors argue that individuals involved in polyamorous relationships should be more likely to have a secure attachment style. Indeed, it would be necessary to access the specificities of polyamory, such as great trust in the partner and low feelings of jealousy (Ritchie & Barker, 2006).

Several data have already been collected to test these hypotheses. Some authors found that individuals involved in CNM relationships or with a positive attitude towards them showed a greater level of security in the attachment dimension and similar or greater relational satisfaction (Ka et al., 2020; Moors et al., 2019; Ritchie & Barker, 2006). Regarding the role of avoidant attachment, Moors et al. (2015) found lower levels of avoidant attachment among CNM individuals compared to monogamous ones. Regarding anxious attachment,, a study evidenced that CNM individuals obtained similar levels compared to monogamous individuals (Moors et al., 2015) and another contribution showed that higher levels of anxious attachment were associated with negative attitudes towards CNM (Fenney & Noller, 1990).

As for other aspects of romantic relationships, associated with attachment and sexual behaviors (Hessler & Katz, 2010; Tull et al., 2012; Vingerhoets et al., 2008), emotion dysregulation may be involved in polyamorous relationships and attitudes towards polyamory. For instance, a good ability to regulate and express positive emotions increases the satisfaction and the psychological well-being in the relationship (Rizor et al., 2017). Furthermore, both sexual compulsivity (i.e., uncontrolled urge to perform sexual acts) and sexual sensation-seeking (i.e., the need for experiencing novel and stimulating sexual experiences) involve a preference for sexual relationships involving multiple partners and are associated with difficulties in regulating and expressing positive emotions (Weiss et al., 2019). Since polyamory involves intimate and sexual relationships with multiple partners (Haritaworn et al., 2006), polyamory is expected to be linked to emotional dysregulation. However, emotion dysregulation levels are associated with poor levels of psychological functioning (Aldao et al., 2010) and low dyadic and sexual satisfaction (Florean & Păsărelu, 2019) and previous studies evidenced that polylovers show similar, or even greater, levels of couple satisfaction (Moors et al., 2015). In addition, although most of polylovers have multiple sexual partners, the construct of polyamory and CNM relationships do not totally overlap. Indeed, some polylovers do not have multiple sexual partners and some individuals having multiple sexual partners are not polylovers (e.g., Scherrer, 2010). Therefore, polylovers are not expected to differ from monogamous individuals on emotion dysregulation levels. Furthermore, since polyamorous individuals may be particularly able to identify and communicate their emotional needs, they may even show lower levels of emotion dysregulation (Yoo et al., 2014). Therefore, although a better understanding of the emotional regulation abilities of polyamorous individuals appears relevant for the understanding of the topic, this has not been investigated yet.

The Present Study

This study aims to extend the knowledge about psychological variables associated with polyamory and attitudes towards polyamory. The first goal is to identify psychological specificities of polylovers in terms of attachment style, emotion dysregulation, and sexual satisfaction. We hypothesized that polylovers, compared to monogamous individuals, will show higher levels of secure attachment and higher levels of sexual satisfaction. Regarding the levels of dysregulation of both negative and positive emotions, no specific hypothesis was formulated because of the lack of previous results on the topic The second set of hypotheses was related to the second aim of the study, namely examining the predictive role of attitudes towards polyamory on sexual satisfaction and the intervening role played by the attachment styles. Since positive attitudes towards polyamory are likely to be associated with sexual assertiveness and since sexual assertiveness has been shown to predict sexual satisfaction, we expected positive attitudes towards polyamory to predict sexual satisfaction among both polyamorous and monogamous individuals. However, since some authors previously suggested that positive attitudes towards polyamory may be the result of insecure attachment styles, which has been shown to negatively predict sexual satisfaction, we hypothesized that avoidant attachment styles may negatively moderate the relationship between attitudes towards polyamory and sexual satisfaction.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The study involved a total of 178 adult participants (20.2% males; 77% females; 1.7% not binary; 1.1% preferred not to specify) recruited through a convenience sampling technique, with a mean of age of 28.66 years (SD = 9.57; age range:18–81 years). 14.6% of participants reported to be single; 11.2% was married; 14.6% was re-married; 1.1% reported to be in a romantic relationship; 57.3% was divorced and 1.1% was separated. The sample was divided in two groups. The group 1 consisted of 76 individuals reporting to be polylovers (17 males; 56 females; 2 not binary; 1 preferred not to specify) and the group 2 of non polylovers (n = 102; 19 males; 81 females; 2 not binary; 1 preferred not to specify). χ2 tests evidenced that the two groups did not differ in gender distribution (χ2 = 1.24; p = .745), average income (χ2 = 5.80; p = .055) and instruction levels (χ2 = .12; p = .730). Similarly, t-test evidenced no statistically significant differences in age between groups (t(176) = − .173; p = .867). Further details about the distribution of the demographic variables are available in Table 1.

The research procedures followed the official guidelines of the American Psychological Association and were approved by the ethics committee of Sapienza University of Rome (N. 181).

An online survey was created on the Eusurvey platform and promoted on social media. At the beginning of the survey, participants were informed about the aims of the study and its guarantee of privacy and anonymity. All the participants completed the questionnaires in all their parts and no missing data was found.

Measures

The Attitudes Towards Polyamory Scale (ATP; Johnson et al., 2015) is the only known measure of attitudes towards polyamorous relationships. It is a self- report instrument, initially consisting of eight items inspired by preconceptions on the topic. The final version is a unidimensional measure with 7 items, assessing attitudes towards polyamory on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree) and has 3 reverse scored items. A high score reflects a positive attitude towards polyamory. Items on the scale included statements about sexually transmitted infections, infidelity, open communication, relationship success, religious beliefs, legal rights, and the ability to love more than one person. The ATP scale showed high internal consistency indicating strong reliability. The ATP demonstrated good psychometric properties, which have been confirmed in our study with good reliability (α = .82).

The Multidimensional Sexuality Questionnaire (MSQ; Snell et al., 1993) was designed to measure psychological inclinations associated with sexual relationships. The tool measures the construct in a multidimensional way, assessing the levels of 12 components of sexuality. For the purpose of this study, a short version of the instrument has been used, excluding subscales which resulted to be insufficiently reliable in previously collected data. The short version of the questionnaire evaluates only the following subscales: sexual esteem, sexual concern, sexual consciousness, sexual motivation, sexual assertiveness, sexual monitoring, sexual fear and sexual satisfaction. The 5-point Likert scale ranges from 0 (not at all characteristic of me) to 4 (very characteristic of me). The subscales of the MSQ showed good internal consistency. Specifically, the Cronbach alphas ranged from .71, for the Sexual- Consciousness Scale, to .94 for the Sexual-Preoccupation Scale.

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Giromini et al., 2012; Gratz & Roemer, 2004) includes 36 items, assessing clinically relevant difficulties in regulating negative emotions. Both the full and short versions, used in this study, are composed of six scales: (1) non acceptance, consisting of items which reflect the tendency to experience negative secondary emotions in response to one’s negative emotions or to have attitudes of non-acceptance with respect to one’s personal distress; (2) goals includes items which investigate the difficulties in focusing and performing a task while experiencing negative emotions; (3) impulse detects the difficulty in maintaining control of the behavior when experiencing negative emotions; (4) awareness contains items which focus on the tendency to pay attention to ones’ emotions and the relative ability to recognize them; (5) strategies reflect the belief that it is particularly difficult to effectively regulate emotions once they have occurred; (6) clarity refers to the ability to clearly recognize and discriminate one’s emotions while experiencing them. The self-report answers are expressed on a 5 points Likert scale ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always). The psychometric properties of the DERS have been confirmed in our study, since all the Cronbach alphas were higher than .70.

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale Positive (DERS-P; Gratz; 2004; Velotti et al., 2020) is a self-report tool consisting of 15 items aimed to assess difficulties in the regulation of positive emotions. The self-report items reflect the subjects' difficulty, concerning emotion regulation, in the following dimensions: Acceptance of positive emotions; Ability to engage in goal-oriented behaviors while experiencing positive emotions; Ability to control impulsive behaviors while experiencing positive emotions. The answers are expressed on a 5 points Likert scale ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always). Higher scores indicate greater difficulty in regulating positive emotions. The DERS-P has demonstrated good psychometric properties which have been confirmed by its good reliability in our study (α = .89).

The Experiences in Close Relationship Scale Short Form (ECR-S; Wei et al., 2007). The ECR-S is used to assess the two insecure dimensions of romantic attachment, namely anxiety and avoidance. The instrument consists of 12 items on a 7-point Likert’ scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree). The subscales of the ECR-S obtained high internal consistency, with an alpha value .73 for the Avoidance subscale and .71 for the Anxiety subscale.

Results

Group Comparisons

A series of analysis of variance, controlling for age and gender and correcting alpha inflation with the Bonferroni method, was performed to test the existence of significant differences between groups on the ECR-S, DERS, DERS-P and MSQ scores. The examination of statistical significances of main effects shown no significant differences regarding ECR-S and DERS scores, whereas the inverse pattern of results emerged regarding DERS-P (Pillai's Trace = .08, p = .003) and MSQ (Pillai's Trace = .23, p < .001) scores. Specifically, polylovers showed higher levels of difficulty in accepting their positive emotions in a non-judgmental way, compared to their non-polylovers counterparts. In addition, polylovers, compared to controls, scored significantly higher on all the MSQ subscales, except for the Fear and Sexual satisfaction ones. Further details are available in Table 2.

Psychological Associations of ATP Among Polylovers

Partial r-Pearson correlations, controlling for Age and Gender, between ATP and all the other variables are described in Table 3. Results show that ATP scores were significantly correlated with some dimensions of MSQ. Specifically, positive associations with Sexual satisfaction (r = .30; p < .05), Sexual consciousness (r = .28; p < .05) and Sexual self-esteem (r = .31; p < .05) were found, whereas a negative and significant correlation was observed with the Sexual fear subscale (r = − .30; p < .05). Furthermore, some significant negative correlations between ATP and difficulties in emotions regulation and attachment dimensions emerged. Specifically, ATP showed a negative association with the DERS clarity subscale (r = − .23; p < .05), the total DERS-P total score (r = − .32; p < .05), the DERS-P Acceptance (r = − .27; p < .05) and Impulse (r = − .33; p < .05) subscales, and the Avoidance (r = − .51; p < .001), and anxiety (r = .30; p < .05) dimensions of the ECR-S.

The Interaction Between ATP and Insecure Attachment in Predicting Sexual Satisfaction

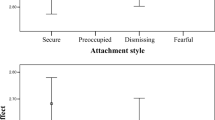

Finally, we tested the hypothesis that attachment dimensions moderate the relationship between polyamorous attitudes and sexual satisfaction on the whole sample. Two distinct moderation models were conducted. In the first model, while controlling for age, sex and avoidance, anxiety did not result to be a significant moderator. On the contrary, a significant and negative interaction effect was observed in the interaction between avoidance and ATP levels in predicting sexual satisfaction (β = − .02; p = .003). Specifically, a significant negative relationship between ATP and sexual satisfaction emerged in case of high levels of avoidance (β = − .14; SD = .05; p = .012), controlling for age, sex, and anxiety (see Fig. 1).

Moderation of avoidant attachment in the relationship between positive attitudes towards polyamory and sexual satisfaction. Note MSQ_SA, Multidimensional Sexuality Questionnaire, Sexual Satisfaction scale; ATP, attitudes towards polyamory Scale; ECRS_A, Experiences in Close Relationship Scale Short Form, Avoidance subscale

Discussion

The main goal of the study was to extend the current knowledge about the role of some psychological variables (i.e., attachment, sexual satisfaction, and emotion dysregulation) in the involvement in polyamorous relationships as well as in the attitudes towards polyamory.

Regarding our first aim, namely identifying the psychological profiles of polylovers compared to monogamous individuals in variables of interest, results were partially in line with our hypotheses. In particular, in the levels of attachment styles, no significant difference was observed between polylovers and monogamous individuals. This data is consistent with a general trend in literature, supported by the fact that this relational configuration is not associated with psychopathological variables and arguing for the need to destigmatize polyamory and (Conley et al., 2013). Then, in line with our hypothesis, results prove that polyamorous individuals show higher levels of sexual satisfaction than non-polyamorous individuals. This finding replicates previous evidences about CNM relationships (i.e., Conley et al., 2018). Eventually, the examination of differences in emotion dysregulation levels between polyamorous and monogamous individuals led to interesting results. The lack of significant differences between groups in the dysregulation of negative emotions suggests that the framework of risky sexual behaviors, strongly related to dysregulation of negative emotions (Weiss et al., 2015b), cannot be employed in the understanding of polyamory. Similarly, results suggest that the psychological profile of polyamorous individuals differ substantially from the profile of individuals with dysfunctions in romantic relationships, such as the perpetrators of intimate partner violence (Velotti et al., 2011). Therefore, our results disconfirmed the idea that the tendency to have multiple partners is related to the attempt to avoid negative emotions within the couple (Waldrop & Resick, 2004; Weiss et al., 2014).

However, we found that polylovers, compared to monogamous individuals, may have greater difficulty in regulating positive emotions and tend to negatively judge their own positive emotions. This finding is especially interesting for two reasons. First of all, it sheds light on the explaining potential of the dysregulation of positive emotions, which is excessively overlooked in the field of clinical psychology (Gruber, 2019). Furthermore, it suggests that potential dysfunctions related to polyamory should not be searched in the field of the negative emotion dysregulation, but rather in relation to pleasant and hedonic triggers (i.e., internal or external events triggering pleasant emotions). For instance, we know that difficulties in accepting positive emotions in a non-judgmental way is connected to the tendency to feel guilty for those emotions, leading to the dampening of positive affects. We may question whether such aspect is related to the specific ethical value associated to CNM (Jónasdóttir & Ferguson, 2013). From this perspective, high moral standards associated to the polyamory philosophy may explain this result. Furthermore, this result may be related to the potential over-representation, among the individuals engaging in CNM relationships, of individuals with some neurobiological characteristics related to the dysregulation of positive emotions (e.g., autism, ADHD). For instance, individuals with autism, who tend to engage in CNM relationships (Sala et al., 2020), may have developed negative metacognitive beliefs about their positive emotions, which may be experienced as dangerous, out of control and leading to the sense of guilt. Although the prevalence rates of autism and other neurobiological disorders, such as ADHD, are not actually known in the population of individuals engaging in CNM relationships and have not been measured in our study, this issue merits further investigation.

Alternatively, individuals with a difficulty to accept their positive emotions are likely to have a compromised capacity to enjoy positive emotions and consequently experience less positive affect. As suggested in the field of addiction, this aspect may foster the research of a highly stimulating lifestyle (i.e., providing high positive sensations), which may be satisfied through multiple romantic relationships.

Our second aim was to test the role of attachment in the relationship between attitudes towards polyamory and sexual satisfaction. Most of our hypotheses were confirmed by the results of the study. First of all, we found that greater positive attitudes towards polyamory were associated to higher levels of sexual satisfaction. This result is consistent with the idea that positive attitudes towards polyamory are likely to be linked to the ability to identify and adequately communicate personal sexual needs (i.e., sexual assertiveness). This capacity has been shown to predict sexual satisfaction (Zhang et al., 2022). In addition, from the perspective of the cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger, 1957), it is not surprising to observe that positive attitudes towards one’s lifestyle predict higher levels of sexual satisfaction, indicating a greater coherence between values and lifestyle, which is a general predictor of life satisfaction (Teerakapibal, 2020). Moreover, positive attitudes towards polyamory were negatively associated with insecure attachment and emotion dysregulation. These findings support the idea that positive attitudes towards polyamory should not be considered pathological or deviant and do not appear to be a defensive mechanism against difficulties in emotional and/or relational functioning. However, the results of the moderation analyses partially mitigated these conclusions. Indeed, it was found that the positive correlation between positive attitudes towards polyamory and sexual satisfaction turned into negative in individuals with high levels of avoidant attachment. This result is in line with the idea that positive attitudes towards polyamory may conceal difficulties in relational functioning among individuals who feel discomfort with closeness and consider relationships as secondary. Indeed, avoidant attachment has been previously shown to be associated with lower levels of relationship satisfaction, including sexual satisfaction, also among polyamorous individuals (Moors et al., 2019). Therefore, in association with such psychological profile, positive attitudes towards polyamory should not reflect a genuine, ethical, and authentic choice, but rather maintain a defensive functioning aimed to deny the importance of intimacy.

From a clinical point of view, the replication of our findings in future contributions, addressing the limitations of our study (see the paragraph below), may have some implications. First of all, the results suggest that positive attitudes towards polyamory and the involvement in polyamorous relationships should not be automatically interpreted as a sign of poor psychological and interpersonal functioning. This observation may contribute to depathologize polyamory and help clinicians to focus on the conditions in which it is likely to be associated with clinically significant problems. Results of the moderation model suggest that, in case the patient with positive attitudes towards polyamory reports poor sexual satisfaction, it may be useful to explore the presence of avoidant attachment. In line with these results, clinicians should be able to discuss with patients their positive attitudes towards polyamory, to explore the potential defensive use of this attitude towards the fear of intimacy and its role in undermining sexual satisfaction.

Limitations and Future Directions

The results and the conclusions of the current study should be considered in light of several limitations. First of all, the topic of CNM is complex, as it includes a wide range of different relational configurations. Therefore, the results of the current study should not be generalized to other configurations and should be replicated in future studies with larger sample size. Therefore, the role of other potentially confounding variables, such as sexual orientation, current number of partners, living situation, and parenthood, has not been examined. Similarly, we measured sexual satisfaction, but we did not exclude asexual individuals, a population where polyamory may be especially popular (Scherrer, 2010). Furthermore, the relational outcomes measured in the study (i.e., sexual satisfaction and romantic attachment) were not referred to a specific partner despite the fact that preliminary results suggested the need to differentiate these variables according to the specific relationship. Therefore, future studies with a wider sample size and a greater statistical power should be aimed to replicate our results, considering the differentiation of the single relationships.

Finally, a central limitation of our study may be related to the convenience sampling technique. In particular, this may have introduced a bias in the results concerning the group of polylovers. Indeed, because of the potentially perceived stigmatization related to their atypical romantic relationships, these participants may have been motivated to participate because of their desire to show that polyamory is not associated with poor psychological functioning and poor relationship satisfaction. In other words, the answers of these participants, compared to those of the comparison group, may be biased by social desirability. Since this variable was not assessed in our study, the estimation of its impact remains unclear and should be explored in future studies. However, despite these limitations, the study suggests several innovative insights to our psychological understanding of the topic of polyamory and significatively extend the current knowledge.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Aldao, A., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Schweizer, S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 217–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203440841

Candel, O. S., & Turliuc, M. N. (2019). Insecure attachment and relationship satisfaction: A meta-analysis of actor and partner associations. Personality and Individual Differences, 147, 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.04.037

Conley, T. D., Matsick, J. L., Moors, A. C., & Ziegler, A. (2017). Investigation of consensually nonmonogamous relationships: Theories, methods, and new directions. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(2), 205–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616667925

Conley, T. D., Piemonte, J. L., Gusakova, S., & Rubin, J. D. (2018). Sexual satisfaction among individuals in monogamous and consensually non-monogamous relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 35(4), 509–531. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407517743078

Conley, T. D., Ziegler, A., Moors, A. C., Matsick, J. L., & Valentine, B. (2013). A critical examination of popular assumptions about the benefits and outcomes of monogamous relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 17(2), 124–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868312467087

Davis, D., Shaver, P. R., & Vernon, M. L. (2004). Attachment style and subjective motivations for sex. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 1076–1090.

Flicker, S. M., Sancier-Barbosa, F., Moors, A. C., & Browne, L. (2021). A closer look at relationship structures: Relationship satisfaction and attachment among people who practice hierarchical and non-hierarchical Polyamory. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50(4), 1401–1417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01875-9

Florean, I. S., & Păsărelu, C. R. (2019). Interpersonal emotion regulation and cognitive empathy as mediators between intrapersonal emotion regulation difficulties and couple satisfaction. Journal of Evidence-Based Psychotherapies, 19(2), 119–134. https://doi.org/10.24193/jebp.2019.2.17

Garofalo, C., Velotti, P., & Zavattini, G. C. (2016). Emotion dysregulation and hypersexuality: Review and clinical implications. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 31(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2015.1062855

Giromini, L., Velotti, P., De Campora, G., Bonalume, L., & Cesare Zavattini, G. (2012). Cultural adaptation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale: Reliability and validity of an Italian version. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68(9), 989–1007. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21876

Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94

Gruber, J. (2019). The Oxford handbook of positive emotion and psychopathology. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190653200.001.0001

Hadden, B. W., Smith, C. V., & Webster, G. D. (2014). Relationship duration moderates associations between attachment and relationship quality: Meta-analytic support for the temporal adult romantic attachment model. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18(1), 42–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868313501885

Haritaworn, J., Lin, C. J., & Klesse, C. (2006). Poly/logue: A critical introduction to polyamory. Sexualities, 9(5), 515–529. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460706069963

Haupert, M. L., Gesselman, A. N., Moors, A. C., Fisher, H. E., & Garcia, J. R. (2017). Prevalence of experiences with consensual nonmonogamous relationships: Findings from two national samples of single Americans. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 43(5), 424–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2016.1178675

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (2017). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. In R. Zukauskiene (Ed.), Interpersonal Development (pp. 283–296). Routledge.

Hessler, D. M., & Katz, L. F. (2010). Brief report: Associations between emotional competence and adolescent risky behavior. Journal of Adolescence, 33(1), 241–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.04.007

Johnson, S. M., Giuliano, T. A., Herselman, J. R., & Hutzler, K. T. (2015). Development of a brief measure of attitudes towards polyamory. Psychology & Sexuality, 6(4), 325–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2014.1001774

Jónasdóttir, A. G., & Ferguson, A. (Eds.). (2013). Love: A question for feminism in the twenty-first century. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315884783

Ka, W. L., Bottcher, S., & Walker, B. R. (2020). Attitudes toward consensual non-monogamy predicted by sociosexual behavior and avoidant attachment. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00941-8

Mark, K. P., & Lasslo, J. A. (2018). Maintaining sexual desire in long-term relationships: A systematic review and conceptual model. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(4–5), 563–581. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2018.1437592

Mitchell, M. E., Bartholomew, K., & Cobb, R. J. (2014). Need fulfillment in polyamorous relationships. The Journal of Sex Research, 51(3), 329–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2012.742998

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). Boosting attachment security to promote mental health, prosocial values, and inter-group tolerance. Psychological Inquiry, 18(3), 139–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/10478400701512646

Moors, A. C., Conley, T. D., Edelstein, R. S., & Chopik, W. J. (2015). Attached to monogamy? Avoidance predicts willingness to engage (but not actual engagement) in consensual non-monogamy. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 32(2), 222–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407514529065

Moors, A. C., Matsick, J. L., & Schechinger, H. A. (2017). Unique and shared relationship benefits of consensually non-monogamous and monogamous relationships: A review and insights for moving forward. European Psychologist, 22(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000278

Moors, A. C., Ryan, W., & Chopik, W. J. (2019). Multiple loves: The effects of attachment with multiple concurrent romantic partners on relational functioning. Personality and Individual Differences, 147, 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.04.023

Ritchie, A., & Barker, M. (2006). ‘There aren’t words for what we do or how we feel so we have to make them up’: Constructing polyamorous languages in a culture of compulsory monogamy. Sexualities, 9(5), 584–601. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460706069987

Rizor, A., Callands, T., Desrosiers, A., & Kershaw, T. (2017). (S) He’s gotta have it: Emotion regulation, emotional expression, and sexual risk behavior in emerging adult couples. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 24(3), 203–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2017.1343700

Sala, G., Hooley, M., & Stokes, M. A. (2020). Romantic intimacy in autism: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 50(11), 4133–4147.

Schachner, D. A., & Shaver, P. R. (2004). Attachment dimensions and motives for sex. Personal Relationships, 11, 179–195.

Scherrer, K. S. (2010). Asexual relationships: What does asexuality have to do with polyamory? Understanding non-monogamies (pp. 154–159). Routledge.

Shaver, P. R., & Mikulincer, M. (2002). Attachment-related psychodynamics. Attachment & Human Development, 4(2), 133–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730210154171

Shaver, P. R., & Mikulincer, M. (2009). An overview of adult attachment theory. In J. H. Obegi & E. Berant (Eds.), Attachment theory and research in clinical work with adults (pp. 17–45). The Guilford Press.

Snell, W. E., Fisher, T. D., & Walters, A. S. (1993). The Multidimensional sexuality questionnaire: An objective self-report measure of psychological tendencies associated with human sexuality. Annals of Sex Research, 6(1), 27–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/107906329300600102

Teerakapibal, S. (2020). Human values and life satisfaction: Moderating effects of culture and age. Journal of Global Marketing, 33(3), 177–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2019.1683668

Tull, M. T., Weiss, N. H., Adams, C. E., & Gratz, K. L. (2012). The contribution of emotion regulation difficulties to risky sexual behavior within a sample of patients in residential substance abuse treatment. Addictive Behaviors, 37(10), 1084–1092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.05.001

Velotti, P., Castellano, R., & Zavattini, G. C. (2011). Adjustment of couples following childbirth: The role of generalized and specific states of mind in an Italian sample. European Psychologist, 16(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000022

Velotti, P., Garofalo, C., Dimaggio, G., & Fonagy, P. (2019). Mindfulness, alexithymia, and empathy moderate relations between trait aggression and antisocial personality disorder traits. Mindfulness, 10(6), 1082–1090. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-1048-3

Velotti, P., Rogier, G., Beomonte Zobel, S., Chirumbolo, A., & Zavattini, G. C. (2022). The relation of anxiety and avoidance dimensions of attachment to intimate partner violence: A meta-analysis about perpetrators. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 23(1), 196–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838020933864

Velotti, P., Rogier, G., Civilla, C., Garofalo, C., Serafini, G., & Amore, M. (2020). Dysregulation of positive emotions across community, clinical and forensic samples using the Italian version of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale-Positive (DERS-Positive). The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 31(4), 555–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2020.1776374

Vingerhoets, A. J., Nyklícek, I., & Denollet, J. (2008). Emotion regulation. The Springer Press.

Waldrop, A. E., & Resick, P. A. (2004). Coping among adult female victims of domestic violence. Journal of Family Violence, 19, 291–302. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOFV.0000042079.91846.68

Wei, M., Russell, D. W., Mallinckrodt, B., & Vogel, D. L. (2007). The Experiences in Close Relationship Scale (ECR)-short form: Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 88(2), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890701268041

Weiss, N. H., Gratz, K. L., & Lavender, J. M. (2015a). Factor structure and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of difficulties in the regulation of positive emotions: The DERS-positive. Behavior Modification, 39(3), 431–453. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445514566504

Weiss, N. H., Sullivan, T. P., & Tull, M. T. (2015b). Explicating the role of emotion dysregulation in risky behaviors: A review and synthesis of the literature with directions for future research and clinical practice. Current Opinion in Psychology, 3, 22–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.01.013

Weiss, N. H., Forkus, S. R., Contractor, A. A., Darosh, A. G., Goncharenko, S., & Dixon-Gordon, K. L. (2019). Do difficulties regulating positive emotions contribute to risky sexual behavior? A path analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(7), 2075–2087. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-1410-0

Weiss, N. H., Duke, A. A., & Sullivan, T. P. (2014). Evidence for a curvilinear dose-response relationship between avoidance coping and drug use problems among women who experience intimate partner violence. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 27(6), 722–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2014.899586

Wosick-Correa, K. (2010). Agreements, rules and agentic fidelity in polyamorous relationships. Psychology & Sexuality, 1(1), 44–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419891003634471

Yoo, H., Bartle-Haring, S., Day, R. D., & Gangamma, R. (2014). Couple communication, emotional and sexual intimacy, and relationship satisfaction. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 40(4), 275–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2012.751072

Zhang, H., Xie, L., Lo, S. S. T., Fan, S., & Yip, P. (2022). Female sexual assertiveness and sexual satisfaction among Chinese couples in Hong Kong: A dyadic approach. The Journal of Sex Research, 59(2), 203–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2021.1875187

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Roma La Sapienza within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. The author(s) reported no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Ethical Standards

The research procedures complied with the official guidelines of the American Psychological Association and were approved by the ethics commitee of Sapienza University of Rome (N. 181).

Informed Consent

Was obtained from all the participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rogier, G., Cisario, G., Juris, L. et al. Attachment Style, Emotion Dysregulation and Sexual Satisfaction Among Polyamorous and Non-polyamorous Individuals. Sexuality & Culture 28, 354–369 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-023-10120-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-023-10120-z