Abstract

Obesity has numerous consequences for the psychosocial and physical functioning of the individual which most often include comorbidities, disorders, and negative social attitudes influencing self-image. These factors indirectly associate obesity with problems in the sphere of sex life. Empirical evidence on this issue is relatively unambiguous but studies that focus on the positive dimensions of sex life do not provide clear-cut conclusions. Previous studies have often been carried out in specific groups and various socio-cultural conditions. The current study analyzed the relationship between sexual satisfaction and a variable describing preferences, expectations, and needs of obese people and non-obese people. Satisfaction was analyzed taking into account two components. One reflected the degree of discrepancy/convergence between the desired and actual frequency of sexual behavior. The other reflected the degree of pleasure felt in connection with actual sexual behavior. The sample consisted of 148 obese people and 128 non-obese people. Three measures were used: the Sexual Activity Questionnaire, Sexual Stimulus Scale, and Sexual Needs and Reaction Scale. The groups did not differ significantly in terms of sexual satisfaction in either dimension. The results of the regression analysis showed a more complex structure of correlations between satisfaction, preferences, expectations, and needs in obese people compared to non-obese people. Also, the activity of the partner, including experiences during full penetration, was found to be most important for pleasure (as one of the dimensions of satisfaction) in the test group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Medical and Psychosocial Aspects of Obesity

According to the criteria proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO), "a person with a BMI of 30 or more is generally considered obese. A person with a BMI equal to or more than 25 is considered overweight" (Health topics. Obesity 2020). WHO also presents unfavourable data on the occurrence of obesity in the world. In 2016, the prevalence of the phenomenon among adults for European countries, Canada, Mexico, South America, and Asia Minor ranged from 20 to 29.9%. In the United States, Turkey, and some countries in North Africa (e.g. Egypt), the prevalence was estimated above 30% (Global Health Observatory [GHO] data 2020). Obesity is a medical problem, especially due to comorbidities and disorders such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, respiratory disorders, osteoarthritis, and reduced mobility, which require therapeutic action. It may coexist with psychosocial problems, such as self-image disorders (especially in terms of the physical self), depression, a sense of stigmatization, and discrimination (Boyes and Latner 2009; Kadioglu et al. 2010; Sarwer and Steffen 2015; Sarwer et al. 2012). Negative social experiences leading to sometimes serious psychological consequences arise primarily from stereotypes and false perceptions about the causes of obesity, the possibility of controlling it, and the personality traits of obese people (Carr et al. 2013; Hall 2018). Obesity is caused by multiple uncontrollable and etiologic personal and environmental factors, such as endocrine disorders, medication, and genetic conditions (Wallace 2004). The psychosocial situation of obese people is also affected by socially shared beliefs regarding appearance and body structure—especially regarding women. Such beliefs are strongly rooted in culture or religion and may differ depending on the region or country. In some cultures where obesity is associated with well-being, beauty, and fertility, obese people are seen as desirable partners. As a result, one can speak of twofold evaluation of the phenomenon of obesity: (1) from a medical, specialist perspective, where it is treated as a problem; (2) from a secular, socio-cultural perspective, where valuation will vary, and will not always be negative. This ambiguity of assessments, reflected in the subjective experiences of obese people, will affect the quality of their lives in various areas, including in the sphere of sex life.

Sexual Functioning of Obese People

Numerous studies on the sexual functioning of obese people focus on positive and negative aspects as well as biological and psychosocial conditions. Positive aspects such as sexual satisfaction, the ability to be aroused and experience orgasm, willingness to engage in intercourse, intensification of sexual activity understood as the frequency of intercourse and the number of partners have been analyzed (Adolfsson et al. 2004; Shao et al. 2015; Younis et al. 2013). Sexual dysfunctions in obese people, the extent of their occurrence and possible etiological factors, have also been explored (Bajos et al. 2010; Han et al. 2011; Kadioglu et al. 2010; Melin et al. 2008; Niolu et al. 2016; Rowland et al. 2017; Simoncig Netjasov et al. 2016; Yazdznpanahi et al. 2016). The observed trends are not unequivocal, especially for sexual activity and satisfaction of obese people. Some results indicate a comparable level of satisfaction for obese and non-obese people (Bajos et al. 2010; Yaylali et al. 2010; Younis et al. 2013), others, more common, show less favorable trends for obese women and men (Adolfsson et al. 2004; Melin et al. 2008; Morotti et al. 2013; Simoncig Netjasov et al. 2016; Yilmaz et al. 2018). The data also show gender differences in the group of obese people, in favor of men who, for example, reveal a higher level of sexual satisfaction and interest, they report having a greater number of partners, and a greater level of sexual activity compared to women. In this respect, they do not differ significantly from non-obese men (Bajos et al. 2010; Kolotkin et al. 2006; Ostbye et al. 2011). Fewer obese women are married than obese men, and their spouses are more often obese/overweight (Bajos et al. 2010; Ostbye et al. 2011). Comparative analyses show less favorable trends in the group of obese people (including adults and adolescents) in the area of safe sexual behavior. Obese people use precautions against STDs (such as condoms) less often and suffer from STDs more frequently—especially obese men (Bajos et al. 2010; Becnel et al. 2017; Nagelkerke et al. 2006). It has also been shown that obese men in the older age group experience sexual violence more often (Adolfsson et al. 2004).

The ambiguity of the trends is dictated, as it seems, by the diversity of the studied groups in terms of age, life situation, health condition, duration of obesity, socio-cultural conditions, adopted parameters for assessing obesity, including Body Mass Index (BMI), Waist Circumference (WC), Waist—Hip Ratio (WHR), and the evaluated period of sexual life (e.g. assessment of the number of partners in the course of a lifetime). Population studies of obese people are rare (Adolfsson et al. 2004; Carr et al. 2013; Han et al. 2011; Kolotkin et al. 2006; Shao et al. 2015). Research on a smaller scale dominates, limited to selected individuals, usually patients of specialist clinics seeking therapy or undergoing one (Becnel et al. 2017; Erbil, 2013; Erenel & Kılınc, 2012; Esposito et al. 2007; Kadioglu et al. 2010; Ostbye et al. 2011; Yaylali et al. 2010; Yazdznpanahi et al. 2016). There are comparative analyses carried out on groups selected using specific criteria (most often the BMI index), e.g. obese people (treated uniformly or broken down into obesity subclasses) and non-obese people. There are also studies where BMI, treated as a continuous variable, is independent of various indicators of sexual functioning. The results of correlation analyses carried out using simple and complex models (such as logistic regression) most often indicate its significant role in shaping sexuality results. Data show that an increase in the BMI index correlates with a decrease in the quality of sex life and higher severity of sexual dysfunctions (Kolotkin et al. 2006; Melin et al., 2008; Poggiogalle et al. 2014). However, some research does not confirm the significant contribution of BMI to shaping sexuality results (Erbil, 2013; Jarząbek-Bielecka et al. 2015; Simoncig Netjasov et al. 2016; Yazdznpanahi et al. 2016) or confirms its significance only for selected aspects of sexual functioning (Yaylali et al. 2010). Some studies have reported a more frequent occurrence of sexual dysfunctions, such as erectile dysfunction in obese men (higher BMI) (Bajos et al. 2010; Han et al. 2011; Morotti et al. 2013), that can potentially be correlated with sexual satisfaction. There are many causes of sexual dysfunctions, including biological ones (Niolu et al. 2016; Sarwer & Steffen, 2015; Sarwer et al. 2012; Simoncig Netjasov et al. 2016). Obese people and overweight people are significantly less satisfied with their physical health and more likely to experience physical limitations, pain, and fatigue (Poggiogalle et al. 2014; Sarwer et al. 2012). This is related to the less favorable assessment of other spheres of life, such as financial status or the possibility of having satisfying leisure time (Adolfsson et al. 2004). Assessment of one's own physical and mental health and the experience of stigmatization and discrimination are important in explaining the low results of sexual satisfaction and sexual activity (Carr et al. 2013). Empirical evidence confirms the existence of a negative relationship between sexual functioning and depression, somatization, obsessive–compulsive disorder, anxiety, hostility, psychoticism, and interpersonal sensitivity (Kadioglu et al. 2010; Morotti et al. 2013; Poggiogalle et al. 2014; Sarwer & Steffen, 2015; Sarwer et al. 2012).

Data illustrating the quantitative and qualitative aspects of the sexual functioning of obese people (the frequency of sexual activity, the number of partners, sexual satisfaction, and intensity of sexual needs) need to be differentiated. This distinction is important for drawing conclusions about the relationship between obesity and sex life. Researchers indicate obesity has an indirect rather than a direct impact on the quality of sexual life. Other factors that have a significant impact are the biological dysfunctions that accompany obesity and the psychosocial aspects embedded in the socio-cultural context related to them. They illustrate the beliefs and evaluation of one’s self expressed in the form of self-esteem, self-image, and the perceived quality of life in its various dimensions. Research to date is not free from limitations, such as the aforementioned focus on specific groups of people seeking specialist help, relatively small samples, age diversity of the respondents, all of which may affect the biological aspect of sexuality (e.g. changes in hormonal processes during menopause), or the age inconsistency of the control and comparison group (Simoncig Netjasov et al. 2016). Some researchers analyzing sexual functioning have focused on individual items and looked for correlations between variables defined by selected items taken from the same measure (Poggiogalle et al. 2014). Some analyses are simple tests of differences or correlation analyses that do not present a multidimensional approach to the phenomenon and its determinants (Erbil, 2013; Jarząbek-Bielecka et al. 2015; Kadioglu et al. 2010; Morotti et al. 2013). These limitations, also noticed by the authors of the studies themselves, and the fact that many studies have been carried out in specific socio-cultural conditions (e.g. Turkey, Egypt, China), justify the need for further analyses of the issue.

The Present Study

The current research focused on positive aspects illustrating sexual satisfaction, preferences, expectations, and needs of obese people. Sexual satisfaction was defined based on literature as an affective response to the fulfillment of one’s own and partner’s sexual needs and expectations, and also those related to the relationship (Offman and Mattheson 2005; Antićewić et al. 2017; Lawrence and Byers 1995; Kvalem et al. 2018). Its components comprise the importance of sexuality, frequency of sexual desire, sexual interest (Adolfsson et al. 2004) frequency of sexual intercourse, sexual variety, and communication about sexuality (Kvalem et al. 2018). In the present research sexual satisfaction was analyzed considering two components: one reflected the degree of discrepancy/convergence between the desired and actual frequency of sexual behavior, the other the degree of pleasure felt in connection with the actual sexual behavior. This method was used to explore the spectrum of experiences which consists of qualitative and quantitative preferences as well as the real availability of their implementation. The undertaken analyses checked the connections of sexual satisfaction understood in this way, using its "D" index: the degree of convergence/divergence, illustrating the tendency for the entire group and the "S" index: determining the individual preferences of the respondent in a given scope against the background of all items analyzed for this individual with the variable describing preferences, expectations, and needs of obese people.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

The study involved 148 obese people and 128 non-obese people. The research was carried out with people from the general adult population who were recruited using the snowball method. This method is sometimes used when there are difficulties with recruiting respondents because of limiting aspects such as social stigmatization, intimate and sensitive issues, or the need for data protection. The presented research concerns intimate issues and respondents represent the population potentially burdened with social stigma. The recruitment started when students carrying out the research, at the promoter's request, contacted national and local associations and foundations supporting obese people. The final and most important criterion was the subjective assessment of one's own obesity, especially the BMI ≥ 30 index. Non-obese people in the comparative group (BMI < 25), were recruited using targeted selection into pairs. The selection criteria were: age, sex, place of residence, marital status, and education attainment, in a distribution, ensuring maximum adjustment to the test group, which, however, was not always possible. All people from both groups were in partner relationships.

Measure

The Sexual Activity Questionnaire (SAQ) Steger and Brockway

SAIQ was created to examine people with spinal cord injury. Steger and Brockway proposed a list of 16 descriptions of heterosexual forms of behavior, including: a man and a woman kiss without a break for a minute, a man massages a woman's naked body, a woman massages a man's naked body, a man caresses woman's breasts with his hands, a man caresses woman's breasts with his mouth, a woman caresses man’s genitals with her hands, a man caresses woman's genitals with his hands, a man caresses woman's genitals with his mouth, a woman caresses man's genitals with her mouth, a man and a woman have intercourse, a man reaches orgasm, a woman reaches orgasm, etc. There are three questions about each of these behaviours: How often did this behavior occur in the last 3 months? How often would you like this behavior to occur? and How pleasant or unpleasant was this behavior? Respondents answer the first two questions on a 4-point scale: 1—not at all, 2—rarely, 3—often, 4—very often. Answers to the third question are given on a 6-point scale: a—very unpleasant, b—moderately unpleasant, c—slightly unpleasant, d—slightly pleasant, e—moderately pleasant, f—very pleasant. Cronbach's alpha, both for the whole scale and individual items, was high; in the first case, it was 0.96 (with standardized alpha 0.97), and in the second from 0.96 to 0.96.

The Sexual Stimulus Scale (SSS)

Created by Lew-Starowicz (1985) was used to learn about respondents’ personal preferences, expectations, and sexual needs, as well as sexual stimuli rejected by them as unpleasant. It can also be used to determine the hierarchy of sexual stimuli associated with the preferred type of masculinity-femininity. Therefore, according to Lew-Starowicz (1985), it is a useful tool in the diagnostic and therapeutic process, and catamnestic research. The scale consists of 30 statements describing sexual forms of activity. The respondents mark on a 4-point scale (from 1—I don’t like it, to 4—I like it very much) how much they prefer a given stimulus or sexual behavior. SSS reliability was estimated for all questionnaire items. Cronbach's alpha for the whole scale was 0.80, with alpha standardized 0.82, while for subscales from 0.73 to 0.77.

The Sexual Needs and Reaction Scale (SNaRS)

This Scale is the author's own instrument based on the Prognostic Scale by Lew-Starowicz (1985), whose original version was the Mell-Krat scale (Lew-Starowicz, 1985), commonly used in sexological, comparative and catamnestic examinations of people with various types of sexual dysfunctions. SNaRS was used to learn about the respondents’ manifestations of their erotic life to determine the level of their erotic functioning and establish their views regarding their sexuality. It consists of 20 statements, 16 scaled characteristics (from 1 to 5 points, with individual points of the scale corresponding to a verbal description adapted to a specific feature), and 4 unscaled, descriptive statements. 10 statements were used from the Prognostic Scale, while others were added from the Mell-Krat scale to adopt the scale for obese people enriching it with issues related to, e.g. the possibility of participating in sexual behavior, and relationship assessment. The scope of issues directly related to sexual intercourse was also simplified. In the present analyses, some of the statements relevant to the issues analyzed here were included.

An interview questionnaire was used to collect sociodemographic data and anthropomorphic information, such as BMI, WHR, and waist circumference.

Methods of Statistical Analysis

Methods of statistical analysis included descriptive measures, tests of differences, correlation, and stepwise linear regression.

In SAQ calculation formulas for the D and S indices were developed. The D index (degree of discrepancy/convergence between the answers to the first and second questions for the 16 statements) was calculated as the 16th root of the squared distances between the individual results of the first and second questions.

p—average of the numerical values for the first question at the level of each scale (k), d—average of the numerical values for the second question at the level of each scale (k), ││ the absolute value.

An analogous formula was used to calculate the S index, but in this case, it concerned the ipsative satisfaction index: the transformation for each of the respondents of the value obtained by them in the third question and subtracting from it the average for their responses to all 16 statements. All calculations were carried out using the STATISTICA 13.3.

Results

Sociodemographic data from both groups and information obtained using SNaRS, SAQ, SSS, and author’s questionnaire are presented in Table 1. The BMI, WHR, and waist circumference indicators are presented only in obese people.

The examined obese people were significantly older, and most of them were married (Table 1). The two groups did not differ significantly in terms of sex, place of permanent residence, educational attainment, and the number of children. Results show that obsess people significantly differed from non-obese people in such manifestations of sexual life as masturbation experience, assessment of the relationship, and assessment of emotional relationship with the partner. Only in masturbation experience their expectations and sexual needs were met more often. On the other hand, for assessment of the relationship, and assessment of emotional relationship with the partner non-obese people rated their relationships significantly higher as more successful, giving a sense of happiness, especially in the area of the emotional bond with the partner as a special aspect of the stability of a sexual relationship. In terms of the number of sexual partners and the intercourse frequency, obese people did not differ significantly from those in the control group. This data was confirmed by subsequent comparative analyses of the D and S indices from the Sexual Activity Questionnaire and 5 categories (factors) of the Sexual Stimulus Scale, where only in the categories Striving for mutual activity (SSS4) and Various sexual positions and fantasies (SSS5) obese people obtained a significant lower average than non-obese people. In the remaining indices of sexual functioning, including satisfaction, differences were not significant. The effect size here are medium and close to average.

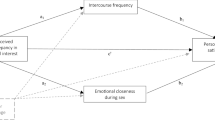

Correlations between sexual satisfaction, using the D and S indices, and five categories describing preferences, expectations, and sexual needs of obese people, were determined using stepwise regression. This method was used to determine the system of explanatory variables that are significant in explaining the dependent variable and estimating the strength of the relationship between them in such a regression model (Tables 4, 5). Earlier, both data sets were correlated using the r-Pearson test (Tables 2, 3).

In the model created for the group of obese people, explaining 9% of the variance of the D index variable, there were two categories of sexual preferences, expectations, and needs at the level of statistical significance (Table 4). This suggests that an increase in the value of this disposition (the degree of differentiation between the occurrence of a given sexual behavior and the demand for it—here with a predominance of demand) is accompanied by a directly proportional increase in preferences in Sexual foreplay, e.g. hugs, kisses on the face and lips. It was found also to be conditioned, however insignificantly, by Striving for mutual activity in the dimensions of various positions and mutual activity during intercourse. In this model, there were also indicators of inversely proportional relationships: the lack of Partner’s activity during intercourse, and also statistically insignificant, Oral-manual activity. On the other hand, the regression model in the same group of obese people for the S index revealed a higher level of variance reaching 16%, with a larger number of explanatory variables, where the intensity of sexual satisfaction was accompanied by Partner’s activity during intercourse. Meanwhile, Sexual foreplay and Striving for mutual activity, categories forming a fusion with the D index remained in opposition to it.

Among the explanatory variables, at the level of statistical significance, in the model proposed for the examined non-obese people was only one category of sexual preferences, expectations, and needs. This model, therefore, explained 6% of the variance of the D index, where the category Partner’s activity during intercourse stood in opposition to it. An even lower level of variance at 5%, was found in this group of respondents in the model for the S index. Hence, none of the five categories of sexual preferences, expectations, and needs correlated at the level of statistical significance (Table 5).

Discussion

The conducted cross-sectional analyses showed that obese people (BMI ≥ 30) do not differ significantly in terms of sexual satisfaction from non-obese people (BMI < 25). This applies to both of its indices: the D index showing the degree of convergence/discrepancy between the desired and actual frequency of sexual behavior and the ipsative index S reflecting the degree of satisfaction (pleasure) felt in connection with the actual sexual behavior. It is difficult to make comparisons to the results of other studies, due to different ways of conceptualizing the variable of satisfaction. Generally, though, other findings confirm the direction of the trend observed here. Younis et al. (2013) claim that obese women express a significantly lower level of sexual satisfaction than non-obese women. Bajos et al. (2010), on the other hand, suggest there are no differences in either of the sexes (compared to the control group) resulting from the BMI index. In both studies, satisfaction was assessed using questions with a ready set of answers describing different levels of satisfaction. A similar tendency, but only in women, indicating the lack of differences in sexual satisfaction (FSFI) related to BMI, was established in Polish studies (Jarząbek-Bielecka et al. 2015).

Positive trends informing about a higher level of physical and emotional satisfaction were found in obese men, compared to men in other weight categories. Obese women were also found to have sexual pleasure more frequently (Shao et al. 2015). Analysis of the results of women collected in a PISQ-12 study (assessment of sexual functioning) showed significant differences in terms of satisfaction with sexual activity to the disadvantage of obese respondents but no differences in sexual desire or the ability to achieve orgasm (Melin et al. 2008). In general, the results of present analyses are closer to the more frequent trend informing about the lack of significant differences between obese people and non-obese people or related to the BMI index analyzed as an independent variable, in terms of broadly understood sexual satisfaction.

In the first dimension of sexual satisfaction (D), there was a trend towards divergence over convergence, which in both groups can be interpreted as a feeling of partner’s insufficient (compared to the needs) sexual activity. Still, this activity provided satisfaction, as evidenced by the S index reflecting the sense of pleasure derived from various forms of sexual activity. These are two different dimensions of sexual functioning: (1) quantitative, showing the intensity of the sexual needs of the respondents in relation to the forms of partner’s sexual activity proposed in the questionnaire, (2) and qualitative expressing the personal experience derived from this activity. We did not analyze the similarities or differences in the intensity of the needs of obese people and non-obese people, but only a subjective sense of satisfaction with their implementation. The needs were assessed in the context of heterosexual partner activity. Referring to its other aspects, such as the number of intercourses or the number of sexual partners, the obtained results suggest they are convergent in both groups. These quantitative aspects of sexual functioning were also analyzed by other researchers. Various trends were observed, such as: more frequent occurrence of sexual intercourse in the group of obese women (Younis et al. 2013); significantly less frequent sexual intercourse and anorgasmia in non-obese women compared to overweight women (Morotti et al. 2013); obese women less often had a recent sexual partner, while there were no differences here between obese and non-obese men; no differences in the frequency of sexual intercourse related to BMI (Bajos et al. 2010); and no significance of BMI for the number of sexual partners in both sexes (Nagelkerke et al. 2006). In analyses involving pre-menopausal women, no differences were found related to BMI in experiencing arousal, sexual desire, or orgasm (Jarząbek-Bielecka et al. 2015).

In the current research, obese people were found to significantly differ from the control group in terms of the overall subjective assessment of partner relationships and the assessment of these relationships’ emotional component. This difference was visible not so much in the positive–negative assessment but in the varying degree of the positive assessment. In both groups, therefore, the relationships were successful and provided the respondents with positive feelings but in the case of non-obese people, the assessment reached the highest scores indicating a very high value of partner relations. Boyes and Latner (2009) established a negative relationship between BMI and the quality of marriage relationships. Respondents' assessment of their relationships was unfavorable, they reported they expected the relationship to end and they felt they did not match their ideal partner. In the present study, more people from the control group were in informal relationships, which may have affected their assessment. Formal relationships carry certain obligations resulting from living together, running a home, and having children. Their implementation, expected from the partner and undertaken by him/her, may be important for the subjective assessment of the relationship.

In addition to engaging in partner activity, most respondents from both groups, who were relatively young (compared to the average), reported to masturbate, and this was more often the case for obese people. This form of sexual need was realized at a rate comparable to that established for the general population (Bancroft, 2011).

Analyzing the sexual preferences, expectations, and needs of respondents from both groups, significant differences were noted for two factors: striving for mutual activity, and various sexual positions and fantasies, in both cases with greater intensity in the control group. Presumably, non-obese people show stronger preferences for forms of intercourse where both partners are active, they look for different ways of achieving sexual pleasure through non-classical positions and more often fantasize during intercourse. Younis et al. (2013) in a study with obese women and non-obese women found no significant differences in preferred sexual positions.

None of the factors differentiating both groups were found to be significant in the regression model for achieving sexual satisfaction, both in terms of convergence-divergence (D) and pleasure (S) in the control group. In both groups, the factor of the partner's activity during intercourse turned out to be significant in the context of satisfaction results analyzed in the D dimension. Thus, a trend was observed where the demand for specific forms of partner activity (discrepancies between the actual and desired frequency of partner’s sexual behavior) co-occurs with weaker preferences of the activity of the male partner leading to penetration and achieving orgasm this way (by both partners). This factor also proved to be important for the results of the sexual satisfaction in obese people determined by how much they experience pleasure (S). Stronger preferences of the described nature, constituting the factor analyzed here, remained in a positive relationship with the pleasure felt during sexual activity with a partner. The satisfaction of people from this group in terms of D and S indices was in a significant relationship with the factor describing the preference for foreplay activities, preceding or not leading to the sexual act. However, this factor created different patterns of connections for both satisfaction indices, because, with increased demand for partner’s sexual activity, which is not satisfied (D), there is a greater preference for staying at the stage of foreplay (kisses and hugs). In turn, greater pleasure derived from partner sex (S) was found to be associated with a lower preference for this type of activity. To sum up, the structure of the relationship between the two aspects of sexual satisfaction and preferences, expectations, and needs is richer in the group of obese people, but only the factor of the male partner activity, including experiences gained during full penetration, has a positive contribution to their sexual pleasure. In both groups, on the other hand, weaker preferences of the male partner activity, and in the case of obese people, increased preferences for foreplay, have the greatest contribution in explaining the discrepancy between the actual and desired frequency of partner’s sexual behavior. The established trends seem logical and consistent. Presumably greater sexual activity with more advanced forms is conducive to strengthening preferences of this nature, especially if the relationship with the partner provides pleasure.

In the current research, sexual satisfaction was analyzed in two ways, taking into account two dimensions: (1) quantitative—the intensity of the need to undertake certain forms of partner activity, and (2) qualitative—determining the degree of pleasure derived from this activity. Such an approach limits reductionism that is visible in the application of a single approach. The frequency of sexual intercourse, orgasms, the number of partners or even the variety of forms of sexual activity should not be essential criteria for assessing the quality of human sex life, however important they are for it (Kvalem et al. 2018). The essence of sex life is the ability to meet one’s own needs (individually differentiated) and preferences, which are shaped by many factors, both personal and social (including socio-cultural conditions). Obesity may have a more indirect impact in this respect, as stated in the introduction. The undertaken analyses do not yield unequivocal conclusions regarding the importance of obesity for sexual experiences, in their positive quantitative dimension, though. Such conclusions would be possible in longitudinal studies or retrospective analyses. Here, we can only talk about common and divergent trends in relation to the control group, which in this case were non-obese people, both in terms of individual aspects of sexual functioning and the analyzed relationships between them. Obesity occurs at different ages affecting some of the already shaped styles of psychosexual functioning, needs, preferences, and ways of implementing them in relationships or non-partner forms, or the process of their crystallization. Depending on the phase of life, it can be important for seeking and choosing a partner, building a relationship or maintaining it. The present research focused on a specific moment in the respondents’ sex life, on its current quantitative and qualitative aspects. The group of obese people studied here was selected from the population, but it was not determined how representative they were of this category. Given this limitation, it is useful to compare it with the results of non-obese people, selected on the basis of certain variables with potential significance (such as age or gender), which gives the possibility to infer about the specifics or similarities in the analyzed areas.

The limitation of the current research may be the use of self-reports but it is justified here because the needs, preferences, and expectations of the respondents were analyzed. The adopted method of data collection, used in the vast majority of studies on sexuality, may impact the accuracy of the results illustrating the quantitative dimension of the sexual functioning of the respondents, such as the number of sexual partners, the frequency of relationships or the extent of masturbation. The snowball method used for recruiting the studied group does not ensure the group’s representativeness, however, taking into account the fact that the presented study concerned intimate issues, it was a useful method for recruiting the group. Population studies are difficult here, and recruiting obese people through specialist clinics could also have disadvantages, such as attracting people who for some reason (e.g. health, image) use their services.

References

Adolfsson, B., Elofsson, S., Rössner, S., & Undén, A. L. (2004). Are sexual dissatisfaction and sexual abuse associated with obesity? A population-based study. Obesity Research, 12(10), 1702–1709.

Antićewić, V., Jokić, N., & Britvić, D. (2017). Sexual self-concept, sexual satisfaction, and attachment among single and coupled individuals. Personal Relationships, 24, 858–868.

Bajos, N., Wellings, K., & Laborde, C. (2010). Sexuality and obesity, a gender perspective: results from French national random probability survey of sexual behaviours. BMJ, 15(340), c2573. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c2573

Bancroft, J. (2011). Human sexuality. Elsevier Urban&Partner.

Becnel, J. L., Zeller, M. H., Noll, J. G., Sarwer, D. B., Reiter-Purtill, J., Michalsky, M., Peugh, J., & Biro, F. M. (2017). Romantic, sexual, and sexual risk behaviours of adolescent females with severe obesity. Pediatric Obesity, 12, 388–397.

Boyes, A. D., & Latner, J. D. (2009). Weight stigma in existing romantic relationships. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 35(4), 282–293.

Brockway, J., & Steger, J. (1978). Sexual attitude and information questionnaire: Reliability and validity in a spinal cord injured population. Paper presented at American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine. New Orleans.

Brockway, J., & Steger, J. (1981). Sexual attitude and information questionnaire: Reliability and validity in a spinal cord injured population. Sexuality and Disability, 4, 49–60.

Carr, D., Murphy, L. F., Batson, H. D., & Springer, A. W. (2013). Bigger is not always better: The effect of obesity on sexual satisfaction and behaviour of adult men in the United States. Men and Masculinities, 16(4), 452–477.

Erbil, N. (2013). The relationships between sexual function, body image, and body mass index among women. Sexuality and Disability, 31, 63–70.

Erenel, A. S., & Kılınc, F. N. (2012). Does obesity increase sexual dysfunction in women? Sexuality and Disability, 31, 53–62.

Esposito, K., Ciotola, M., Giugliano, F., Bisogni, C., Schisano, B., Autorino, R., Cobellis, L., De Sio, M., Colacurci, N., & Giugliano, D. (2007). Association of body weight with sexual function in women. International Journal of Impotence Research, 19, 353–357.

Global Health Observatory (GHO) data (2020) https://www.who.int/gho/ncd/risk_factors/overweight/en/. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

Hall, O. M. (2018). Fat women’s experiences of navigating sex and sexuality. http://www.wsanz.org.nz/journal/docs/WSJNZ32Hall10-20.pdf. Retrieved February 5, 2020

Han, T. S., Tajar, A., O’Neill, T. W., Jiangm, M., Bartfai, G., Boonen, S., Casanueva, F., Finn, J. D., Forti, G., Giwercman, A., Huhtaniemi, I. T., Kula, K., Pendleton, N., Punab, M., Silman, A. J., Vanderschueren, D., Lean, M. E., Wu, F. C., & EMAS Group. (2011). Impaired quality of life and sexual function in overweight and obese men: The European Male Ageing Study. European Journal of Endocrinology, 164(6), 1003–1011.

Health topics. (2020). Obesity. https://www.who.int/topics/obesity/en/. Retrieved February 5, 2020

Jarząbek-Bielecka, G., Wilczak, M., Potasińska-Sobkowska, A., Pisarska-Krawczyk, M., Mizgier, M., Andrzejak, K., Kędzia, W., & Sajdak, S. (2015). Overweight, obesity and female sexuality in perimenopause: A preliminary report. Menopauzal Review [Przegląd Menopauzalny], 14(2), 97–104.

Kadioglu, P., Yetkin, D. O., Sanli, O., Yalin, A. S., Onem, K., & Kadioglu, A. (2010). Obesity might not be a risk factor for female sexual dysfunction. BJU International, 106(9), 1357–1361.

Kolotkin, R. L., Binks, M., Crosby, R. D., Østbye, T., Gress, R. E., & Adams, T. D. (2006). Obesity and sexual quality of life. Obesity, 14(3), 472–479.

Kvalem, I. L., Træen, B., Markovic, A., & von Soest, T. (2018). Body image development and sexual satisfaction: A prospective study from adolescence to adulthood. The Journal of Sex Research, 56(6), 791–801.

Lew-Starowicz, Z. (1985). Treatment of functional sexual dysfunction. Medical PZWL.

LoPiccolo, J., & Steger, J. (1974). The sexual interaction inventory: A new instrument for assessment of sexual dysfunction. Archives of Sexual Behaviors, 3(6), 585–595.

Melin, I., Falconer, C., Rossner, S., & Altman, D. (2008). Sexual function in obese women: Impact of lower urinary tract dysfunction. International Journal of Obesity, 32, 1312–1318.

Morotti, E., Battaglia, B., Paradisi, R., Persico, N., Zampieri, M., Venturoli, S., & Battaglia, C. (2013). Body mass index, Stunkard Figure Rating Scale, and sexuality in young Italian women: A pilot study. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10, 1034–1043.

Nagelkerke, N. J. D., Bernsen, R., Sgaier, S., & Jha, P. (2006). Body mass index, sexual behaviour, and sexually transmitted infections: An analysis using the NHANES 1999–2000 data. BMC Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-6-199

Niolu, C., Bianciardi, E., & Siracusano, A. (2016). Gender differences in sexual dysfunctions among individuals with obesity. Italian Journal of Gender-Specific Medicine, 2(2), 69–74.

Ostbye, T., Kolotkin, R. L., He, H., Overcash, F., Brouwer, R., Binks, M., Syrjala, K. L., & Gadde, K. M. (2011). Sexual functioning in obese adults enrolling in a weight loss study. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 37(3), 224–235.

Poggiogalle, E., Di Lazzaro, L., Pinto, A., Migliaccio, S., Lenzi, A., & Donini, L. M. (2014). Health-related quality of life and quality of sexual life in obese subjects. International Journal of Endocrinology. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/847871.2014

Rowland, D. L., McNabney, S. M., & Mann, A. R. (2017). Sexual function, obesity, and weight loss in men and women. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 5(3), 323–338.

Sarwer, D. B., & Steffen, K. J. (2015). Quality of life, body image and sexual functioning in bariatric surgery patients. European Eating Disorders Review, 23(6), 504–508.

Sarwer, D. B., Lavery, M., & Spitzer, J. C. (2012). A review of the relationships between extreme obesity, quality of life, and sexual function. Obesity Surgery, 22, 668–676.

Shao, Z., Zhan, J., Li, H., & He, Q. (2015). Associations among body mass index and sexual behaviour and sexual health in Chinese adults. Health Behavior and Policy Review, 2(4), 243–250.

Simoncig Netjasov, A., Tančić-Gajić, M., Ivović, M., Marina, L., Arizanović, Z., & Vujović, S. (2016). Influence of obesity and hormone disturbances on sexuality of women in the menopause. Gynecological Endocrinology, 32(9), 762–766.

Wallace, R. A. (2004). Risk factors for coronary artery disease among individuals with rare syndrome intellectual disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 1(1), 42–51.

Yaylali, G. F., Tekekoglu, S., & Akin, F. (2010). Sexual dysfunction in obese and overweight women. International Journal of Impotence Research, 22, 220–226.

Yazdznpanahi, Z., Beygi, Z., Akbarzadeh, M., & Zare, N. (2016). Investigating the relationships between obesity and sexual function and its components. Shiraz E-Medical Journal, 17(9), 1–7.

Yilmaz, F. T., Kumsar, A. K., & Demirel, G. (2018). The effect of body image on sexual quality of life in obese married women. Health Care for Women International. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2018.1542432

Younis, I., Abdelrahman, S. H., Abdelfattah, M. I., & Al-Awady, M. A. (2013). Can obesity affect female sexuality? Human Andrology, 3(4), 98–106.

Funding

This study was not funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

MP declares that she has no conflict of interest. JK declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Parchomiuk, M., Kirenko, J. Sexual Satisfaction in Obese People. Sexuality & Culture 25, 1588–1604 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-021-09836-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-021-09836-7