Abstract

This article examines how disability and sexuality are represented in today’s Russian media, and how disabled people navigate these understandings. Drawing on online storytelling and first person stories about sexuality told by disabled people in the public sphere, the article provides a qualitative account of people with disabilities, journalists and civil rights advocates, analyzing how contemporary Russians with disabilities narrate their own lives in public forums. The focus of their stories, as well as the accounts of eyewitnesses, volunteers in the institutions, is on the constraints and limits of sexuality and intimacy spheres imposed by the professionals, families and wider society. This article also interprets the narratives behind disabled people’s sexuality circulating in contemporary Russia through digital networks, in combination with qualitative data from primary sources: disability activists and two journalists with and without disability in Moscow. It is argued that the telling of these stories in a public forum is a political act. In personal stories about sexual, bodily experiences told in the interviews or autobiographical texts, self-presentations and discussions in social networks, the voices of people are heard, permitting emancipation from previous categories. However, disability always remains with them, playing an important role in social lives of these people and in their sexual experiences and identities, becoming the cornerstone of the personal and collective re-defining of themselves. Using ideas of “visibility politics” (Arendt), queer/crip kinship and intimate citizenship (Plummer), the authors demonstrate how someone might choose to speak publicly about a topic and how this understanding develops cultural understandings of contemporary Russia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“When I put on a colored prosthesis, children come up to me on the street: for them I am a superhero. When I go to the mirror naked, I admire my body. I am a cyborg diva. And it’s normal”. Tatiana Demianova, whose words are quoted in the popular weekly newspaper “Argumenty i facty” (Ivanushkina 2018), is a head IT engineer at Sberbank, one of the largest banks in the country, as well as an athlete, fashion model, writer and motivational speaker. Her appearances in mass media, Facebook and Instagram is usually followed by bright and beautiful photo images and always contain a political statement about overcoming stigma, dismantling taboo, and building solidarity. In her childhood, the doctors mistakenly diagnosed her with a fracture while she had osteomyelitis, a hand rotted under a plaster and was amputated. She has been hiding her stump under the clothes and wearing cosmetic prostheses. She had romantic relations but only for one night, the men expressed curiosity or made jokes. “But this summer, - she says, - a miracle happened to me. I undressed in front of a man and felt beautiful. I removed the cosmetic prosthesis and set it aside. For the first time in my life, I didn’t apologize. I do not have a hand, and the stump is scarred. But every scar tells my story. For many years I did not look at my left hand in the mirror. And now I was looking at a handsome man - and was a beautiful woman.” (Ivanushkina 2018).

Cyborg Diva is telling her stories for herself and for the others: “The theme of “the arm” was a taboo in our family for 30 years from 1988 until 2018… For the first time, in the beginning of this year… I told a man about my hand, not waiting for him to find out. And the world did not collapse.” The hardest thing for her was to develop a romantic relationship as she was afraid of disclosing her “defect” to a partner. Her story continues: “Then… my mom said: “Previously, I used to think it was a tragedy, too”. You see?” (cyborgdiva 2018). This became a great turning point in the life of Tatiana and was associated with her family sharing her emergence from the “depths of pain”. “It’s no longer a taboo”, as Tatiana puts it.

Cyborg Diva’s statements in the public sphere stand as an example of how social practices of current disability sexuality in Russia include representation as a political act. Sexuality and intimacy are formed in social interaction in accordance with the intersubjective meanings attributed to culture and the inner, subjective meanings created by individuals. A variety of social practices in modern sexuality bear the imprint of normalizing discourses that operate on a wide continuum from family and kinship to popular culture, legislation and specialized expert knowledge. Social control is exercised over individuals within the sphere of sexuality, privacy, and intimacy by various means. This control, however, can be weakened, manipulated, and ridiculed. Talking about sexuality is no longer a taboo for some people with disabilities; instead it can become a form of activism.

Based on the ideas of Hanna Arendt and “visibility politics” (Arendt 1958), this article examines the coming-out acts of people with disabilities, narratives of “intimate citizenship” (as formulated by Ken Plummer 1995), stories of the body, gender and sexuality, which, being personal in the beginning, become political when their authors go into the public sphere, redefining normalcy and claiming recognition for those who are usually silent and silenced by the dominating majority. By public sphere we understand “mediated publicness” available within the private realms via technology that shifted the classic divide of public/private (Thompson 2011) and enabled oppressed and invisible people to interact with each other, to initiate public discussions of previously silenced issues. Using ideas of queer/crip kinship and intimate citizenship we draw on online storytelling and first-person stories about sexuality told by disabled people in the public sphere to demonstrate how someone might choose to speak publicly about the topic and how these narratives reflect cultural understandings of sexuality in contemporary Russia.

The goal of this article is to explain how disability and sexuality are represented in today’s Russian media, and how disabled people navigate these representations. The article will use examples from the public sphere and qualitative interview data to show how the stories voiced by the people with disabilities offer a variable format for building one’s own sexual identity, and also direct social changes in the perception of sexualities. We are interested in how personal stories of sexuality are produced and what conditions make them sound in public. How are they interpreted and what role do they play in the political and social transformations of post-Soviet experiences? How are the barriers to intimate citizenship erected, made flexible or dismantled?

Shifting Boundaries of Disability and Sexuality in Academic and Public Discourses

This section reviews the existing literature discussing disability and sexuality as a starting point to reflect upon the issues of intimacy and disability in the context of post-socialism. We rely on the theories of the public sphere and intimate citizenship in addition to queer and disability theories. The term “disability” is understood here as a complex social and cultural construction resulting from the interaction between the environment and individual and wider conditions in society (Oliver 1990). At the same time, it is important to emphasize the bodily experience of living with disability. When social institutions reduce disabled people to their impairment, they de-gender and de-sexualize them (Iarskaia-Smirnova 2011). Yet, we should acknowledge the agency of people with disabilities and their networks, their endeavors to advocate their rights and dismantle the barriers set by socio-political structures, including in the sexual experiences.

Historically “[t]here has been an excited discourse around disabled people’s sexuality as inherently kinky, bizarre and exotic” (Kafer 2003: 85). In the West, the topic of disabled people’s sexuality emerged in the 1960s as part of the concept of normalization, understood as the expansion of usual normal life in conceptual terms (Williams and Nind 1999: 669) that includes not only home and work, but sex and marriage. However, the discourse of normalization did not take into account gender differences or was defined in biodeterministic terms, with control over sexual life delegated to the professionals (Williams and Nind 1999: 669). Sexuality arises in a discourse in connection with control over reproduction and with an emphasis on sexual health rather than sexual pleasure.

Although in the 1980s a new ideology of normalization emerged, aspects of the old eugenics continue to exist, which manifests itself in a societal fear and hostility towards the disabled. People with learning difficulties are denied the ability to perform “normal” (including sexual) sex roles. “Normal” society is stratified by sex and patriarchy, therefore everything that is “normal” in relation to intimacy and sexuality was created and differentiated on the basis of social inequality (Williams and Nind 1999: 666). Stereotypes about disabled people as eternal children (immature and asexual) in need of constant protection and treatment mixed with concerns about them as sexually problematic, dangerous potential abusers, and from the point of view of genetically transmitted pathology are reproduced in mass consciousness, political and academic discourse.

While in the West this topic entered the field of academic discussion in the 1980s and was influenced by social movements (Campling 1981; Oliver 1990), in Russia the issue of gender identity and sexuality in relation to disability was not addressed in sociological studies nor in public discourse until recently. One should bear in mind the extreme level of compulsory isolation (Kondakov 2018: 83) experienced by the disabled throughout the Soviet history and, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union and transition to democracy in the 1990s, the process of de-institutionalization. In 1980 one Soviet representative was asked by a Western journalist whether or not Soviet Union would participate in the first Paralympic games in Great Britain. The puzzling answer was “There are no invalids in the USSR!” (Fefelov 1986; Phillips 2009). Six years later, during a television debate involving American and Soviet audiences, a Boston woman asked the Soviet participants of the show whether their TV advertisements were overwhelmed with sex as American commercials were. A woman from Leningrad answered: “There is no sex here, and we are absolutely opposed to it”. Some other women added: “we do have sex, we have no such ads!” but their voices drowned in laughter from both sides of the television bridge (“Zhenshhiny govorjat s zhenshhinami”, 1986). These two popular catchphrases encompass an issue of invisible citizens and a tabooed subject. Silencing the topics of sex and disability in public discourses is still in place in post-socialist countries (Mladenov 2014). In many ways, this is a legacy of state socialism which embodied a victory of modernism with its rationalist social planning and control over the human body. Modernity required healthy bodies for standardized labor while intimacy was shadowed by the issues of reproduction, fertility, and public health policies. This wide net of institutions and discourses of biopolitics (Foucault 2003) included the ways people used to think about able-bodiedness and disability (Iarskaia-Smirnova et al. 2015).

Since the 1990s reflections on sexuality and disability have been discussed by experts in Russian mass media (press and TV shows) and sexology literature. The talk show “About it [Pro eto]”, which focused on love and sex and was broadcasted on TV from 1997 to 2002 (see Gradskova in this issue), devoted an episode to the sexual life of people with disabilities. In the 1990s and 2000s translated literature on sexology was published and the magazine “Social Protection” created a section entitled “Sex for the Elderly and Disabled” in 1998. In this newspaper, many publications about the sex of people with disabilities, made on behalf of Russian psychologists, sex therapists in the 2000s, were highly medical in nature (Iarskaia-Smirnova 2001). They discuss sexual disorders, the severity of these disorders, the temperament of patients with epilepsy and diabetes, personality changes, decreases in sexual performance, impaired sperm production and ejaculation, and even about children with disabilities as the consequences of late birth.

In contrast, articles in the magazine “Sex for the Elderly and Disabled” that are translated from other languages (e.g. Swedish) shed light on the sexual practices of people with disabilities, the misfortunes and joys of intimate intercourse, the role sex plays in the development of a person, in his/her personal life, family, relationships with parents, about the past and the future. People with disabilities here are not shown as victims or patients, but individuals included in multiple social connections, playing diverse social roles in unexpected or familiar circumstances, in family, at work, and at school. These are the sexual biographies of successful people who overcome isolation, shame and self-doubt, fully and with great dedication participating in life of the society. Furthermore, the gender identity of a disabled person may create different opportunities for men and women. All authors of the texts in the mentioned above edition were men; women appear in the texts as the object of male fantasies and desires, as a means of realizing the sexuality of the disabled man, and finally, as the partner in marriage, intimate and parental relationships. The popular texts on gender and sex normalize persons with disabilities within the limits of heterosexuality.

In contemporary Russia, as Alexander Kondakov (2018: 75) has argued, the government generally marginalizes and isolates homosexuals and the disabled “through discourses of contagion”. The physical isolation that was typical for the Soviet times, has replaced in conditions of post-socialist neoliberalism by the prohibition from appearing queer or disabled in public (Kondakov 2018: 75). Recent studies focus on the dominance of normative over the “disabled body” sexuality (Esmail et al. 2010), and on interrelations of crip (which is short for cripple) and queer. McRuer (2006) explains how the dominant economic and cultural system of contemporary capitalist society implies compulsory able-bodiedness and heterosexuality. Neoliberalism, following McRuer, stigmatizes disability and queerness and promotes ableism as a system that privileges able-bodied members of society through institutional and cultural norms (Hartblay 2015). In response, however, disability and queer identities are produced and they open up the possibilities for formation of the crip and queer movements. The appearance of a “crip” in public provokes and actively works to undo ableism (McRuer 2006), confronting discrimination and exclusion. The word crip in the Western literature and social movements practice is associated with advocating the rights and justice for people with disabilities, while “queer” stands for LGBT solidarity (Hartblay 2015) and acceptance of different sexualities.

Yet, notions of human rights and disabled people’s movements may not be successful in such places and times where and when dissent is under strict control and the voices of the marginalized are silenced. Independent living can be impossible when families face chronic poverty and states lack the resources to provide basic education and healthcare, when they are left without personal assistants, occupational therapy and an accessible environment (Rasell and Iarskaia-Smirnova 2014). Nonetheless, even in contexts like this sexualities and, in a broader sense, intimacies, have “re-entered the public sphere” and currently rely on the intersection of sexuality and disability. This happened in post-soviet Russia with the topics of sexuality becoming the objects of state and market power based on the “patriarchally naturalized pursuit of rule” (Swader and Obelene 2015: 247, 245).

Open conversations about sexuality, sexual education and sexual needs were possible in the 1990s and beginning of the 2000s, but became a cultural taboo and even “illegal” with the revival of religious discourses, traditional family values and patriotism in the society as a whole. According to a public opinion survey of 2016, among the most “uncomfortable” topics, the strictest taboos are conversations about sexuality (33%). On the other hand, 47% are not afraid to discuss any topic (Levada Center 2017). Moreover, private actors, the family and the social surrounding, also play a vital role in either promoting or prohibiting open discussion of sexuality and intimacy.

Liberal and conservative attitudes mixed and fought under conditions of political and economic instability, patriarchal renaissance and commercialization. Intimacy politics in Russia “serve as a master key for understanding political and economic patriarchy” (Swader and Obelene 2015: 246). The first studies on the analysis of popular images of disability and sexuality appeared in Russia in the 2000s (Iarskaia-Smirnova 2002), and, more recently, in a breakthrough anthropological novel by Anna Klepikova (2018). The narratives of family, kinship, sexuality, responsibility, and citizenship map new journeys for people with disabilities and engage researchers in new discoveries (Phillips 2011; Hartblay 2014; Iarskaia-Smirnova 2001, 2002, 2011). After the decades of being an object of social control and medical policing, the gender and sexual identity of a person with disability can now become a resource for resisting normalizing stereotypes. Although it was for a long time a taboo subject and in many respects is still prohibited by family, society, media and mass culture, talking about intimacy has become a usual practice and tool for emancipation and liberation.

How do we make sense of these new developments? One way to approach them is through analyzing sexual story telling. Plummer insists that in modern conditions our choice of sexual identity becomes a value and a political choice, alike the electoral choice. In this sense, one’s personal story of sexuality becomes a social action and a way of self-presentation. Thus, it is important to problematize the process of telling sexual stories and “sexual storytelling” as a format of public speaking. The concept of “intimate citizenship” suggests “a cluster of emerging concerns over the rights to choose what we do with our bodies, our feelings, our identities, our relationships, our genders, our eroticisms and our representations” (Plummer 1995:17). Hence, it is important to turn to narrative structures that help reveal both the effects of normative ideas and stereotypical attitudes on personal experiences and identities (Kattari 2015), as well as creative subjective meanings that allow individuals to make choices and fully participate in the intimate citizenship.

In this study, our attention is primarily focused on stories that are voiced in public sphere: media narratives, personal stories published in social networks and autobiography editions. The narrators and commentators of these stories are, in terms of Arendt, actors and sufferers (Arendt 1958: 183), social agents who insert themselves into the human world with word and deed, to confirm their appearance. This insertion may be stimulated by the presence of others; but it is always a beginning of something new, of one’s own initiative (Arendt 1958: 176–177). Thus, the appearance of the disabled body and sound of voices of people with disabilities in public sphere helps to make such experiences visible in society and offers a chance to communicate and assert their own identity as a resource for collective judgment and action.

A sexual biography, a story of intimate citizenship that has been submitted to public discourse, can reinforce prejudices but it can also deconstruct social myths about people with disabilities and become a tool of fighting for identity. Following Arendt (1958), when somebody discloses oneself appearing in public space through action, (s)he always falls into an already existing web of human relationships which exists wherever people live together. A new process “eventually emerges as the unique life story of the newcomer, affects uniquely the life stories of all those who are in contact” with that actor (Arendt 1958: 184). This “web” mentioned by Arendt, subsequently found form in the universe of internet, a public realm where people with disabilities are taking the risk of disclosing themselves as agents in the act of telling their stories (Arendt 1958: 180). According to Ken Plummer, telling sexual stories is a political process, and analyzing sex stories is not just curiosity or voyeurism. It is central to understanding the work of sexual politics in the modern world, where essentialism and tolerance are replaced by recognition and joy of differences, power from below, power through participation (Plummer 1995: 151).

In the non-western context of the post-socialist countries, scholars must recognize social (in)justice concerning specific contexts and axes of difference (Mladenov 2017). Given the conditions in Russia where activism often takes quasi-public forms, “queer/crip kinship may concentrate on its own network of relations without paying any particular attention to existing institutionalized powers or openly making demands to authorities” (Kondakov 2018: 85). However, some do appear in the public sphere that enhance a sense of humor and sense of self in a comedy of recognition (Hartblay 2015: 212). They use the terms “invalid”, “DeTsePeshnik”Footnote 1 (a man with cerebral palsy), “urod” (ugly/freak) “as an indication of pride and solidarity, a refusal to think inside existing aesthetic standards” (Kondakov 2018: 84). Denying the rules of appearance, they do not hide their “ugliness” but use creative verbal and visual means to liberate themselves from stigma. Telling sexual stories in public becomes political tool to acquire intimate citizenship (Plummer 1995) under the conditions of political and economic patriarchy.

The next section seeks to analyze how contemporary Russians with disabilities narrate their own lives in public forums, including media reports, personal memoirs, activist interviews, and comment threads. The focus of their stories, as well as the accounts of eyewitnesses, volunteers in the institutions, is on the constraints and limits of sexuality and intimacy spheres imposed by professionals, families and wider society.

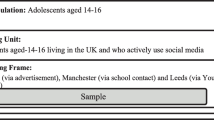

To explore how the politics of representation of sexuality and disability is co-created through online media storytelling and self-reflected in personal stories and activist narratives, we examined media storytelling articles published by Russian online media on behalf of disabled people who write on the topic of sexuality (“Wonderzine”, “Meduza”, “Takie dela”, “Neinvalid.ru”, “Miloserdie.ru”, 2016–2019). In our analysis we focused on the content and context of the stories, the structures and social role of narratives (Labov and Waletzky 1997). The articles were chosen according to topic relevance and genre along two criteria: 1) the story was told by a person with disability; 2) sexuality and disability issues were covered. Ten articles were found that corresponded to these two criteria. Additionally, we monitored statements in threads devoted to sexuality and disability in social media and online forums (2013–2018). These statements were used to deepen understanding of self-assessments and self-representations of people with disabilities in terms of sexuality and gender.

Some of the authors of such statements cited in this article approved of the use of their quotes and original names, while others were anonymized or provided with pseudonyms. Among the possible limitations of these types of data analysis are the unmeasurable impact of journalists in the construction of personal narratives, given “silent” stories are not spoken publicly due to the cultural barriers of the post-Soviet societies, and the sheer scope of personal reasons or trauma (Zaviršek 2010). Striving to overcome such limitations, we have reviewed expert knowledge. For this reason, additional data was included in the form of two in-depth expert interviews with prominent disability activists and an interview with a journalist who is writing for Miloserdie.ru (Russian online orthodox media). The interviews were conducted by the authors of this article in 2017–2018 in Moscow with the support of the Russian Science Foundation grant N°18-18-00321.

Sexual Storytelling: Discourses and Practices of Control

Since “able-bodiedness, heterosexism, and misogyny are made as an acknowledged, integral part of the government’s policies” (Kondakov 2018: 83), disability calls for non-normative sexualities. Often in mass culture and media “people with disabilities are cast in “deviant” roles or are excluded from participation in typical kinship patterns” (Hartblay 2015: 362). Long-existing cultural practices of control and normalization of sexuality transform into a system of personal taboos and collective stereotypes which are exposed in media narratives of persons with disabilities and expert interviews.

Media texts and social networks commentaries on sexual and gender behavior that we analyze further mostly touch the relationship with the opposite sex, i.e., public discourse normalizes persons with disabilities within heterosexuality. It is important to note, however, that the life experiences of people with disabilities in Russia do not fit the narrow categories of normative sexualities reproduced by public discourses (Kondakov 2018: 80–81). A piece of forum commentary retrieved from a popular Russian online platform (Intimnye uslugi) for disability issues discussion illustrates the normative pressure of heterosexuality. Even the imagined situation of the intimate relationship is driven into the socially acceptable norm of heterosexuality:

Probably, the thing is that after 35 years of life I have not had sex with anyone, either with girls or boys, and the sexual tension is really massive, and it looks for a way out, sometimes in homo-fantasies. But I try to kick away these homo-fantasies. How hard it is to live as a DeTsePshnik, inside four walls, without the opportunity to go out, to meet a girl (statement from the forum discussion dedicated to the sexual life of people with disabilities on Dislife.ru, 2013–2015; user is registered as a man of 41 y.o.)

Particularly stable and non-reflective are the norms of constrained sexuality reproduced within the segregated institutionalized life space where the children and adults with various disabilities live. The residents of such institutions, especially people with mental disabilities, have a minimum of private spaces to appropriate, their private life is under the strict surveillance of staff. Issues of sex education are acute there (Sumskiene and Orlova, 2015). As a result, the discussion is avoided and it is believed that a particular child, and then a teenager and a young adult, has not matured sufficiently to be exposed to such knowledge.

The medicalized control of sexuality is accompanied by the cultural control, which is reinforced through the stereotypes of deviant hypersexuality of a person with disability, especially in a case of mental ones, as well as through the hyperpublicity of the very space of the institution, where even the bathroom often may not be private. The situation is aggravated by the lack of professional assistive practices that could eliminate the risks of stigmatization and become the basis for a reflexive approach to the many-sided experiences of body and sexuality. Under conditions of neoliberal post-socialist capitalism, the necessary sources for care and compassion are unavailable (Kondakov 2018: 85).

The diaries of the volunteers and expert interviews in mass-media suggest that, inside institutions, practices of controlling sexuality can take the form of harsh punishment and stigmatization, gendered selective approval or the complete disregard of sexuality (Sumskiene and Orlova 2015; Klepikova, 2018). Attitudes toward a boy, a teenager, a man and his manifestations of sexual behavior can be perceived as a manifestation of the norm with which the code of perception of the male body in traditional culture is inextricably linked. At the same time, early manifestations of sexuality in boys and adolescents may be stigmatized and perceived as degeneration, a display of “preoccupation,” a deviation that is subject to correction. In Anna Klepikova’s 2018 anthropological novel, which is based on her extensive field work at institutions for children and adults with mental disabilities, several instances were recorded:

According to the tutor, he [the eldest child in the group] “was good, but became more degenerate.” First, just because of the “concern” and magazines [with “half-naked girls”]… his interest in the sexual sphere of life increased, as it turns out, not as part of the natural stage in the development of a teenager (Klepikova 2018: 34–35).

The lack of comprehensive educational practices, a system of support for parents and staff consultations, leads not only to the suppression of sexuality, but the active intervention of corrective specialists, teachers and volunteers, who deploy a repertoire of symbolic instruments from “strict taboo” to the substitution of sexual desire with “positive” spiritual, intellectual or physical activities:

Imagine: you are twenty years old. You experience sexual desire for the people around you, to the actors from the movies you watch. But at the same time you can’t find a sexual partner nor even help yourself, because your arms are paralyzed […] Teachers and volunteers believed that it was necessary to switch his sexual energy to other areas - to physical therapy classes or to train literacy and text typing skills at a computer, religious people talked to him about taming the flesh, someone believed that a psychologist was needed. All this may be true, but no one could help Igor in the simplest solution of the problem. (Klepikova 2018: 319).

Narratives of people with disabilities in mass-media provoke moral and spiritual values issues that regulate ideas about sex and permissible sexual behavior. Steady stereotypes of the “asexuality” of people with disabilities in combination with religious values of spiritual and moral “purity” of the “suffering” disabled body become regulators of everyday judgment and behavior not only for people with disabilities, but also for the community of professionals, parents, volunteers and activists who form their inner circle. Mladenov (2014) regards the desexualization of disabled people as a form of disablism that is sustained through medicalization and patriarchal stereotypes and stigma attached to bodily difference.

The main questions that appear in media publications and social media commentaries reveal the challenges of finding a sexual partner under the pressure of legitimizing cultural stereotypes. A young man is concerned with use of commercial sex services: is it acceptable without emotional attachment, spiritual intimacy?

Several times I’ve got an idea to call for a sex worker, but my parents were totally against it. And indeed, when I think about it, a lot of fears immediately appear in my head: what if a priestess of love (zhritsa lyubvi: sex worker) would see me and would not want to carry out such a service? (the story of a young man with cerebral palsy, interview for Meduza: Kravtsova 2018)

In a situation of physical, social and cultural isolation, people with disabilities are often deprived of the opportunity to resort to other scenarios of sexual relations or use assistive technologies. In addition, public conversation on the sexual life of people with disabilities inevitably turns to the argument of ignoring sexual needs in favor of spiritual development. Denying sexual needs may seem the only way but does not solve the central problem. The story of this young man is built on the interaction between three heroes, each of which symbolizes the corresponding types of narratives—the search for one’s own sexuality (the young man himself), the debatable norm and the search for avoiding its pressure (mother), the observance of the norm and the denial of sexuality (father):

I am afraid that people with strong Orthodox beliefs will condemn me for my desires, for example. It is expected that I should not dream of such a thing, isn’t it? (the story of a young man with a profound cerebral palsy, interview for Meduza: Kravtsova 2018)

When the young man takes the initiative and talks with me about it, we talk. But how to help him, I do not know. The husband took a different position: he is sure that since the monks live without carnal pleasures, it means that there is nothing terrible and [our son] will survive [without them]. I try to argue with him: after all, the monks themselves chose such a path, but our son did not (the parents’ reactions from the same story, interview for Meduza: Kravtsova 2018)

Sacrifice and rejection of the body are considered the most obvious and legitimate way out of a situation in which social conditions and cultural stereotypes deny the need to search for space and resources to build individual sexual identity. Other stories of people with disabilities, reveal an open set of values that treats sexuality as a personal choice. Moreover, talking about sexuality in public becomes a tool for building a community, a place for sharing and caring, and a political act for disabled people in today’s Russia.

Networking and Personal Choice in Sexual Stories

The system of limitations and constraints embodied through practices and discourses have for a long time been producing “conditions of marginalization by making certain populations contagious and restricting their accessibility to the public sphere” (Kondakov 2018: 83). In response, mutual relations are enhanced and communities of care are built in private realms (Phillips 2011; Kondakov 2018). At the same time, in the public sphere, too, processes of recognition are on the rise. Media narratives produced and co-produced by journalists and persons with disabilities illuminate the ways where the narrow categories of normative sexuality are redefined by the open set of values and personal choice of sexuality. Vibrant web actors and ordinary users of social networks with their personal stories raise important political issues of independent living, accepting their own sexuality, inverting and dismantling the stereotypes and taboos.

In the narrative of these stories, the topic of sex can emerge spontaneously as one of the fragments of the lifestyle and routine, authors’ achievements and failures, personal evaluation of surrounding people and events. The plots conform to several generic genres mentioned by Plummer (1995: 107): suffering, coming out and surviving. Storytelling narratives offer stimuli for public reflexive conversation about the limits of institutional pressure, the balance of individual and collective in contemporary identity projects. In his interview to online media, Ivan, a creative developer of assistive IT applications for people with disabilities, discusses his personal experience and the difficulties associated with independent living for people with cerebral palsy and other types of disabilities. The message is that the issues of sexual life are inseparable from the politics of independent life, the infrastructure of which is only emerging in Russia:

Cerebral palsy guys [DeTsePeshki] have the following problem: if you live with your family, then you cannot have sex. But this is not good. At the heart of my desire for independence is the desire to have a sex life. For a person without speech, tactile communication is very important. (Ivan, 17 years old, active public figure, IT specialist, interview for online media: Morozova 2018)

Men and women’s stories share experiences on how to subvert and resist the cultural ban of sexuality and “asexuality” assumption. The drama of the oral story in the genre of coming out, starts with the painful internalization of the dominant cultural norms to embody asexuality at certain stage(s) of life, goes on through the subsequent stages of accepting oneself and one’s own body, overcoming the traumatic scenario of normalization, in search for new formats of sexuality, ending with the final re-establishing of oneself and sharing of new self-knowledge with others. Narrators insist on the visibility of personal stories of sexuality, that should be told aloud, and this can also be regarded as a significant element of disability politics. An example of such a statement may be the story of the Cyborg Diva, who described the difficulties of accepting herself and her history of fighting her own and societal stereotypes. The story guides the reader through the stages of suffering and survival offering a scenario of conscious overcoming of trauma and discomfort:

I was afraid to undress in front of a man, because I thought that my left hand was a portal of evil, and it could not be shown to anyone. I thought that no one needed me (although I did not admit it to myself). Unfortunately, another thing was connected with the lack of a hand – the desire to part with virginity “at any cost”, otherwise I would not fit into the standard of “normality” that I wanted to fit into […] This also applies to ordinary people who don’t feel their worth. It’s just that people with a peculiarity are more difficult to handle, because the “babushka” of Public Opinion believes we are a burden… It is very important to love and accept yourself. Sometimes it is not only about comfort, but also about life itself. Take care of yourself! (cyborgdiva 2019)

The audience of her Instagram account praise the posts and comment about their emotions and thoughts, contributing with their own impressions and experiences.

Traditionally the body of a disabled person is the object of the gaze of others—the public, doctors, photographers, researchers. However, people with disabilities use this “social gaze” and beautification instruments as resources to construct their personal and collective embodiment identity through media narratives. New aesthetics of the body are constructed in social media profiles and beauty blogs. We analyzed examples of such stories in the Instagram of the show presenter and sportsman with a bionic prosthesis Dmitry Ignatov (dvignatov 2019) or the popular YouTube beauty vlog of a young Russian woman with genetic peculiarities Lili Lo (liliylis 2019). The visibility of the physical body in the shifting boundaries of private and public realms of social media makes the story comprehensible to the multiple audiences both in terms of Arendt’s classical notion of “situated visibility of co-presence” and Thompson’s more recent concept of “mediated visibility” (Thompson 2011).

The spaces of mediated visibility help to unlock the potential contexts of enacting disability policies “from below”. However, according to disability activist opinions articulated in the expert interviews conducted during field research, Russian grassroots communities of people with disabilities have weak cohesion and low protest potential in comparison to disability movement in the West and other civil initiatives in Russia:

The LGBT movement [in Russia] is a protest. People are not accepted, they are deleted from the agenda of most media outlets, and all they can do is protest, from which they become stronger. With disability it is much more complicated, because everything is different: the state takes care of disabled people, builds some ramps […] Therefore, such a sense of justice that you need to go and defend your rights is not observed yet. (interview with Evgeniy, 22 y.o., LGBT activist and disability youth leader, Moscow, 2017)

He argues that in Russian sociocultural context, strong horizontal links between civil LGBT initiatives and public organizations of people with disabilities have not yet been established. This problem is rooted, to his mind, in the oppressive powers of homophobic stereotypes, legal discourses and public opinion. The informant claims that people with disabilities who support LGBT movement or simply do not fit into the standards of normative sexuality, in fact, are trapped and held down by a powerful stigma.

Discounting the topic of sexuality of disabled people affects also “self-censorship in the disability movement itself” (Shildrick 2007: 226). In public organizations and the grassroots of people with disabilities, according to Evgeniy, this topic remains unvoiced and stigmatized, and access to LGBT initiatives is often limited by low mobility and disruption of social contacts:

These people [with disabilities] are invisible in the LGBT community for obvious reasons: there is no accessibility [of environment] and it is not clear how, in principle, this community is ready to accept them. And in the communities of people with disabilities - there the story is even tougher, because all these homophobic stereotypes, of course, also affect people with disabilities. (interview with Evgeniy, 22 y.o., LGBT activist and disability youth leader, Moscow, 2017)

The queer/crip kinship is based on social commonalities, political solidarity, and emotional compassion (Kondakov 2018: 83), it has political and intimate dimensions, provides care and pride. But Evgeniy points out the limits of such community and challenges its permeability. So, in reality, not all may employ “a queer political strategy” or enjoy “a crip network of care” (Kondakov 2018: 85) as joining or building one’s own queer/crip kinship maybe a matter of an exceptional chance.

Some groups may be more hermetical than others towards different grounds of otherness. Disability groups often base their social closure on the type of impairment and may be hostile towards non-impaired individuals and share anti-queer attitudes. While entering a concrete group or community may become a challenge and not always possible for a person who may not associate her/himself with that group identity, queerness understood and accepted as otherness becomes a resource of reflectivity and activism. Talking about sexuality helps create and sustain queer/crip kinship that “becomes a political location of resistance, where a variety of personal experiences come together to combat disposability and isolation” (Kondakov 2018: 85).

Media storytelling shows that people with disabilities, becoming actors and authors, characters and tellers of sexual stories, try to go beyond the narrow confines of the category of disability and resist such images that stigmatize them. “Flexible” media spaces—personal accounts on social networks, popular Internet publications (personal stories in Wonderzine, Such Matters [Takie dela], Medusa), autobiographical books, groups in social networks and forums contribute to this to a greater extent. These web-forum discussions manifest what Barchunova and Parfenova (2010) call “liquid sexuality”, meaning flexible intimacy practices of men and women with disabilities concerning the choice of a partner.

The topic of sexuality of people with disabilities and personal history as a whole becomes the resource that, on the one hand, responds to the request of the audience, on the other,—promotes the issues of the rights to live a full life by a person with disabilities. “Everyone is tired of celebrities and politics. Today, the audience is interested in the life of each of us, it attracts attention,”—this is how one of our interviewees, a journalist (Miloserdie.ru, June, 2017, Moscow) explained the motives for the media to turn to personal stories of people with disabilities. The appearance of these stories makes it impossible to ignore the topic and end the existence of the “metanarrative” of the solely approved norm of sexuality (Plummer 1995). While previously, as our informants, the activists and journalists say, they had to fight to highlight the violation of disabled people’s rights and prove its relevance to the media agenda, now it may become a conventional part of a journalist job. However, there is a danger that the point of saturation may be reached if readers are overloaded with such themes. Investigating this question is a new challenge for further research on the sexuality and disability personal stories.

The boundaries of private/public, as well as the limits of transparency, have become matters of reflection and revision. When to speak out and when to keep silent has become a matter of personal choice and self-definition, and in some cases, what was considered personal, intimate in the past, is political in the current period. Activists and experts mentioned two significant autobiographical narratives published in Russia during the 2000s. Personal life stories of the well-known Russian female journalists with disabilities triggered public discussions on the private female experiences of disability, including sexual life. Irina Yasina, the author of the book Istoriya Bolezni (“The Disease History”) first published in 2011 (Yasina 2012), describes in her interview the generational shift towards an open discussion of the sexuality of women with disabilities. She addresses the narration style in a book of her colleague Evgeniya Voskoboinikova entitled “Istoriya odnogo pereloma” (“The Story of a Break”) published in 2017 (Voskoboynikova and Chukovskaya 2017):

Though, I didn’t tell everything. I kept a lot of things out of my book. By the way, Zhenya Voskoboinikova wrote a book and it is franker. There she describes […] she is paralyzed below the waist, but she is pregnant. Personal things need to be explained, like how she feels during sexual activity (interview with Irina, 55 y.o., journalist and disability activist, Moscow, 2017)

It is important to note that both women are active political actors and public figures. Irina Yasina is a prominent journalist and economist, one of the founders of Open Russia Foundation in 2001, a writer and disability advocate. Evgenia Voskoboinikova is a fashion model, a journalist and one of the founding team members of the oppositional television channel “Dozhd” (The Rain).

While for some people with disabilities talking about sexuality is not a taboo but normal thing and even a political act, many others do not speak publicly or really, even in “private” to family and friends about their intimate sphere. Thus, it can be said that their sexual needs are suppressed. In the previous section we discussed the constraints imposed by residential frames, institutions and families, and above all, by the mass culture, religious beliefs and wider societal assumptions that are still in place on a large scale. However, in this section, we presented the types of sexual narratives that reach out the public and challenge the repressive picture.

Conclusion

In this article we have discussed sexuality of people with disabilities, something that has become the object of social control and power manipulations. We have shown that even under the conditions of silencing the issues of disability and intimacy some people might choose to speak publicly about the topic and their narratives reflect cultural understandings of sexuality in contemporary Russia. Uncovering the topic of “disabled sexuality” sheds light on the political and socio-cultural transformations of post-Soviet modernity in Russia. The ideas inherent to social hostility are still present in some images of people with disabilities in popular culture and in stigmatizing attitudes within society. Social control over the sexual identity of persons with disabilities is expressed in medicalized and grotesque images of sexual experience of persons with disabilities in public discourse; the “normal” heterosexuality of people with disabilities is presented in rare cases, while the queer identity is silenced. The way in which the issues of “disabled sexuality” are presented in Russian society reflects the renaissance of conservative ideology in the post-Soviet Russia. The solution of many social problems is increasingly seen in the strengthening of the traditional family, the reconstruction of the patriarchal gender order and the implementation of pronatalist demographic policies.

At the same time, new social stories of sexuality are appearing in public sphere. Persons with disabilities resist stereotypical discourses, making choice and self-determination central to their sexual stories. For a person with disability it is just as important, and sometimes even more important than for everyone else, to focus primarily on their gender identity, occupation, hobbies, family, and sexual life, to feel like a human being, not as the embodiment of diagnosis. Men and women refuse to remain within the limits of category of disability, at the same time drawing on it the resources of collective identification. Resisting prejudices in society and in their self-images, people with disabilities deconstruct and reconstruct their gender and sexual identities. Resistance to disabling discourse sometimes occurs through the formation of solidarity with other oppressed social groups. Solidarity ties and care relations are being developed, the queer/crip kinship established. At the same time, the availability of such communities of care is a matter of accepting, of recognition and inclusion. Differential inclusion takes place when the values of a person and the group do not correspond or the social closure mechanisms do not permit the entrance for an outsider.

When otherness is welcomed, kinship becomes a source of positive identity, group belonging and gives the strength necessary for resistance. Families may or may not become a part of that circle. Rigid institutional arrangements build barriers to intimate citizenship but channel personal sexual stories through social networks. With the help of journalists or disability activists, these stories become a part of revelation and liberation process. Stories of the body, gender and sexuality, being personal in the beginning, become political when their authors-protagonists go into the public sphere, redefining normalcy and claiming recognition and representation for those who are usually silent and silenced by the dominating majority. In personal stories about sexual, bodily experiences told in the interviews or autobiographical texts, self-presentations and discussions in social networks, voices of people who have become closely within the category of disability are heard. However, disability always remains with them, playing an important role in social lives of these people and in their sexual experiences and identities, and therefore becomes the cornerstone of the personal and collective re-defining of themselves. The feeling of queer/crip kinship becomes a source of solidarity and manifestation of one’s voice in public sphere in various formats of participation. The sexual identity of persons with disabilities is under close control by society with its requirements of normativity and a modernist understanding of subjectivity. This is reflected in the ways sexual identities and experiences of persons with disabilities are medicalized and exoticized, treated as problematic or silenced in institutional discourses and mass-media.

The idea of queer/crip kinship has its institutional embodiment and borders. Some disability communities are homophobic, individuals with disabilities and their families often share religious beliefs which may erect barriers towards queer identities and suppress sexual talks. Disability is shaped by various conditions, including gender, material well-being, health, education, geographic location, local politics and culture, availability of assistance or independent living. Sometimes groups and communities are inaccessible for the disabled as well as public spaces and social services. In this regard, the role of such public figures as Tatiana Demianova, Ivan Bakaidov, Irina Yasina, Evgenia Voskoboinikova is extremely important. They become the role models speaking in public, dismantling stereotypes and overcoming stigma, challenging public opinion and societal arrangements, provoking changes in attitudes and forms of communication. They are agents of visibility politics for people with disabilities. Telling sexual stories becomes one of the forms of agency that subvert official practices and shape disabled people’s lives and strategies today.

The analysis of representations of disability and sexuality in articles of the Internet media in the genre of storytelling show how sexuality of people with disabilities becomes a significant resource for their self-representation in today’s Russian media and a tool for journalistic expression. Quotes from the interviews with people with disabilities concerning the problems of sexual life are often put in the heading of materials, they become an independent section of the reportage, are emphasized in the text and are complemented by attractive photo images. The storytelling format itself offers effective performative resources for representing the diversity of individual experiences of disability and sexuality, while the narrative of a person with disability breaks the silence and supports the others to come out to advocate for the rights to recognition.

Notes

ДЦП (pronounced DeTsePe) means cerebral palsy in Russian. Thus, a sufferer of this condition can be called DeTsePeshnik.

References

Arendt, H. (1958). Human condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Barchunova, T., Parfenova, O. (2010). Shift-F2: The internet, mass media, and female-to-female intimate relations in Krasnoyarsk and Novosibirsk. Laboratorium: Russian Review of Social Research,2(3), 150–172.

Campling, J. (1981). Images of ourselves: Disabled women talking. Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Dmitry Ignatov. (2019). Retrieved September 15, 2019, from, https://www.instagram.com/dvignatov/?hl=ru.

Esmail, S., Darry, K., Walter, A., & Knupp, H. (2010). Attitudes and perceptions towards disability and sexuality. Disability and Rehabilitation,32(14), 1148–1155.

Fefelov, V. (1986). V SSSR invalidov net! (There are no invalids in the USSR!). London: Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd.

Foucault, M. (2003). Governmentality. In P. Rabinow & N. Rose (Eds.), The essential Foucault: Selections from essential works of Foucault 1954–1984 (pp. 229–245). London: The New Press.

Hartblay, C. (2014). Welcome to Sergeichburg: Disability, crip performance, and the comedy of recognition in Russia. Journal of Social Policy Studies,12(1), 111–124.

Hartblay, C. (2015). Inaccessible accessibility: An ethnographic account of disability and globalization in contemporary Russia. PhD dissertation, submitted to University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Iarskaia-Smirnova, E. (2001). Social change and self-empowerment: Stories of disabled people in Russia. In M. Priestley (Ed.), Disability and the life course: Global perspectives (pp. 101–112). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Iarskaia-Smirnova, E. (2002). Stigma “invalidnoj” seksual’nosti. [The stigma of “disabled” sexuality]. In E. Zdravomyslova & A. Temkina (Eds.), V poiskah seksual’nosti (pp. 223–244). Saint Petersburg: Dmitrij Bulanin.

Iarskaia-Smirnova, E. (2011). “A girl who liked to dance”: Life experiences of Russian women with motor impairments. In M. Jäppinen, M. Kulmala, & A. Saarinen (Eds.), Gazing at welfare, gender and agency in post-socialist countries (pp. 104–124). Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars.

Iarskaia-Smirnova, E., Romanov, P., & Yarskaya, V. (2015). Parenting children with disabilities in Russia: Institutions, discourses and identities. Europe-Asia Studies,67(10), 1606–1634.

Iarskaja-Smirnova, E. (2002). Stigma “invalidnoj” seksual’nosti. [The stigma of “disabled” sexuality]. In E. Zdravomyslova & A. Temkina (Eds.), V poiskah seksual’nosti (pp. 223–244). Saint Petersburg: Dmitrij Bulanin.

Intimnye uslugi, tem kto ne mozhet najti sebe partnera (Intimate services for those who cannot find a partner). Forum discussion on Dislife.ru. Retrieved April 13, 2019, from https://dislife.ru/forum/viewtopic.php?f=65&t=1149&start=20.

Ivanushkina, P. (2018). Cyborg-diva. The story of a girl who lost her arm and found herself, 24.12.2008. Retrieved September 15, 2019, from http://www.aif.ru/society/people/kiborg-diva_istoriya_devushki_poteryavshey_ruku_i_obretshey_sebya.

Kafer, A. (2003). Compulsory bodies: Reflections on heterosexuality and able-bodiedness. Journal of Women’s History,15(3), 77–89.

Kattari, S. K. (2015). “Getting It”: Identity and sexual communication for sexual and gender Minorities with physical disabilities. Sexuality and Culture,19(4), 882–899.

Klepikova, A. (2018). Naverno ya durak. Saint Petersburg: European University at St. Petersburg.

Kondakov, A. (2018). Crip kinship: A political strategy of people who were deemed contagious by the shirtless putin. Feminist Formations,30(1), 71–90.

Kravtsova, I. (2018). “Bojus’, chto za moi zhelanija menja osudjat”. Ljudi s invalidnost’ju hotjat seksa i govorjat ob jetom — no v Rossii ih nikto ne slushaet (“I’m afraid that people will condemn me for my desires”. People with disabilities want sex and talk about it - but in Russia no one listens to them). Meduza. Retrieved May 12, 2019, from https://meduza.io/feature/2018/11/12/boyus-chto-za-moi-zhelaniya-menya-osudyat.

Labov, W., & Waletzky, J. (1997). Narrative analysis: Oral versions of personal experience. Journal of Narrative & Life History,7(1–4), 3–38.

Levada Center. (2017). “Forbidden topics” press release on the results of the opinion poll held in November, 18–21 2016. Retrieved September 15, 2019, from http://www.levada.ru/2017/01/10/zapretnye-temy/.

Lili Lo. (2019). Retrieved September 15, 2019, from https://www.youtube.com/user/liliylis.

McRuer, R. (2006). Crip theory: Cultural signs of queerness and disability. New York: New York University Press.

Mladenov, T. (2014). Breaking the silence: Disability and sexuality in contemporary Bulgaria, Disability in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union: History, policy and everyday life. In M. Rasell & E. Iarskaia-Smirnova (Eds.), Breaking the silence: Disability and sexuality in contemporary Bulgaria (pp. 141–164). London: Routledge.

Mladenov, T. (2017). Postsocialist disability matrix. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research,19(2), 104–117.

Morozova, K. (2018). Istorija gika s DeTseP iz Peterburga, kotorogo nominirovali na premiju OON (The story of a geek with cerebral palsy from St. Petersburg, who was nominated for the UN Prize). Sobaka.ru. Retrieved May 12, 2019, from http://www.sobaka.ru/city/city/99073.

Oliver, M. (1990). The politics of disablement: A sociological approach. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Phillips, S. (2009). There are no invalids in the USSR!: A missing Soviet chapter in the new disability history. Disability Studies Quarterly, 29(3). Retrieved September 15, 2019, from https://dsq-sds.org/article/view/936/1111.

Phillips, S. (2011). Disability and mobile citizenship in postsocialist Ukraine. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Plummer, K. (1995). Telling sexual stories in a late modern world. Studies in Symbolic Interaction,18, 101–120.

Rasell, M., & Iarskaia-Smirnova, E. (2014). Conceptualising disability in Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union. In E. Iarskaia-Smirnova & M. Rasell (Eds.), Disability in Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union History, policy and everyday life (pp. 1–117). Abingdon, NY: Routledge.

Shildrick, M. (2007). Dangerous discourses: Anxiety, desire, and disability. Studies in Gender and Sexuality,8(3), 221–244.

Sumskiene, E., & Orlova, U. L. (2015). Sexuality of ‘Dehumanized People’ across post-soviet countries: Patterns from closed residential care institutions in Lithuania. Sexuality & Culture,19, 369.

Swader, Ch., & Obelene, V. (2015). Post-Soviet intimacies: An introduction. Sexuality and Culture,19(2), 245–255.

Tatiana4demyanova. cyborgdiva. (2018). https://www.instagram.com/p/BpTq6vYBLgw/ Accessed September, 15 2019.

Tatiana4demyanova. cyborgdiva. (2019). Retrieved September 15, 2019, from https://www.instazu.com/media/1953841128839479260.

Thompson, J. B. (2011). Shifting boundaries of public and private life. Theory, Culture & Society,28(4), 49–70.

Voskoboynikova, E., & Chukovskaya, A. (2017). Na moem meste. Istorija odnogo pereloma [In my place. The story of a Break]. Individuum.

Williams, L., & Nind, M. (1999). Insiders and Outsiders: Normalisation and women with learning difficulties. Disability and Society,14(5), 659–672.

Yasina, I. (2012). Istoriya bolezni: v popytkakh byt’ stchastlinoi [The Disease History: trying to be happy]. Moscow: Corpus (ACT).

Zaviršek, D. (2010). Vospominaniya invalidov o seksual’nom nasilii: fakty i umolchaniya [Disabled recollections of sexual violence: facts and silences]. The Journal of Social Policy Studies,7(3), 349–380.

Zhenshhiny govorjat s zhenshhinami (“Women speak to women”). (1986). A Russian language fragment of the video with the quote “There is no sex in USSR”. Retrieved to September 13, 2019, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y0FTbeKGPjM.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express appreciation to Alexander Kondakov, Yulia Gradskova, Maryna Shevtsova, anonymous reviewers for valuable and constructive suggestions during this article improvement process and Matthew Blackburn for editing of English translation.

Funding

The article was prepared within the framework of the HSE University Basic Research Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no potential conflicts of interest regarding this paper.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Iarskaia-Smirnova, E., Verbilovich, V. “It’s No Longer Taboo, is It?” Stories of Intimate Citizenship of People with Disabilities in Today’s Russian Public Sphere. Sexuality & Culture 24, 428–446 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-019-09699-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-019-09699-z