Abstract

Condoms have been highlighted as one of the most effective strategies to prevent the spread of HIV and AIDS. This study assessed how adolescents and parents perceive the condom distribution programme in selected secondary schools in the high-density suburbs of Bulawayo. A concurrent mixed method survey was conducted on three selected secondary schools. Three hundred adolescents and three hundred parents responded to a pre tested semi structured questionnaire. Likert scales were developed to assess knowledge and attitude levels. The χ2 test and multiple logistic regression were used to associate different demographic characteristics with attitudes and levels of knowledge regarding condom distribution at schools using STATA Version 13. Practices and beliefs were assessed using unstructured interviews on purposively selected adolescents and parents. Qualitative data collected was thematically analysed on MAXQDA. The response rate was 100% and 81% for adolescents and parents/guardians respectively. There were more females than males in both response groups. About 67% of adolescents and 60% of parents/guardians were knowledgeable about condom usage and its implications on prevention of spread of sexually transmitted infections and pregnancies. A large proportion of parents/adolescents (72%) had good attitudes towards condom distribution in schools compared to adolescents (27%). Age was strongly associated with knowledge in adolescents, with older adolescent 102 times more likely to be knowledgeable compared to younger adolescents. Religion was the strongest predictor of attitudes in parents/guardians with Catholic having an odds of 227. The concerned sexual health institutions should increase awareness among adolescents, targeting their attitudes towards condom distribution and usage. Targeting attitudes will hopefully foster safe sexual practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adolescents learn more from the social environment they live in and fulfill their sexual desires through experimentation. These adolescents are often guided by their parents who in most cases do not approve early engagement in sex (Trinh et al. 2009). Adolescents are tempted to engage in sexual activities, and this exposes them to many sex-related risks (Boohene et al. 1991). Nations have been challenged under Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) number 3.7 to ensure universal access to sexual health care services (Griggs et al. 2017; Pradhan et al. 2017). For this SDG to be achieved, there is need to provide a supportive environment that would ensure adolescents develop and maintain good sexual health seeking behaviour (Griggs et al. 2017; Pradhan et al. 2017). Perceptions of condom use by adolescents and parents is an important component of the public health strategy to prevent the transmission of sexually transmitted diseases and early pregnancies (Moore and Rosenthal 1991). The greatest concern about Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) is that there is no cure nor vaccine (Grace 1995). To avoid contracting an HIV infection, an individual has to either totally abstain from sexual activity or use prevention methods such as condoms (United Nations 2000).

Condom use has been deemed an effective way of reducing HIV infection and unwanted pregnancies (Cates 2001). Parents and adolescents should be equipped with understanding on the current prevention programmes, since they interact on day to day basis (Stanton et al. 2015). Elucidation of the perception of parents and adolescents regarding condom use will likely have important implications on HIV prevention for adolescents especially (Pequegnat and Bray 1997). Understanding adolescents’ opinions and beliefs about condom use and sexual activities can serve as a starting point for any country to reduce the chances of Sexually Transmitted Infections’ (STIs) transmission and early pregnancies (Stanton et al. 2015; Trinh et al. 2009).

Despite positive views by parents and adolescents on condom use, there are some untrue and scientifically-baseless beliefs that sex with a young girl prevents HIV infection whilst sex with virgin (including children and babies) cures Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) (Smith 2002). This then leads to high chances of adolescents being abused by the people they stay with in their communities (Smith 2002).

Some cultural beliefs such as wife inheritance commonly known as Nhaka in the Shona Language do not encourage condom use, and this may increase risks of contracting STIs (Castrì et al. 2009). There is no doubt that unprotected sex among adolescents leads to early pregnancies which can result in complications during birth due to incomplete physiological body growth, anaemia, inadequate knowledge, and low use of reproductive health services (Stanton et al. 2015; Trinh et al. 2009). A 2015 Demographic Health Survey in Zimbabwe showed that 22% of adolescent females aged 15–19 in Zimbabwe have begun childbearing (Care 2016). These figures may be due to lack of knowledge fuelled by educational gap and lack of contraception measures between parents and children (United Nations 2000). In a cultural ceremony that was televised nationwide in Zimbabwe, older women examined a group of female adolescents to ascertain their virginity status (Marindo et al. 2003). Those found to be virgins were honoured by the society and given certificates with the theme “warriors against AIDS” sponsored by “True Love Waits” clubs (Marindo et al. 2003). These ceremonies are meant to promote abstinence and discourage young people from engaging in risky sexual activities (Marindo et al. 2003). Although 86,806 female condoms and 878,516 male condoms were distributed in public and private premises in Bulawayo, sexual transmitted diseases within adolescents still persist. National AIDS Council (2016) indicated 18.7% HIV prevalence and an estimated pregnancy of 11% among Bulawayo adolescents (Care 2016).

Due to poverty, transactional and intergenerational sex has led to high increase in AIDS cases in developing countries (Rumano 2009). Due to harsh economic conditions in Sub Saharan Africa (SSA), adolescents often engage in sexual activities with adults, in exchange for monetary benefits (Luke and Kurz 2002). These adolescents are more often than not, taken advantage of, and have less decision making powers when it comes to whether or not to indulge in protected sex (Rumano 2009).

It has also been reported by some scholars in Zimbabwe that old man become violent if young girls suggest to use a condom (Rumano 2009). Typically, the young adolescent gives in and are left at risk of contracting STIs and falling pregnant, and this scenario would in turn jeopardise their future (Luke and Kurz 2002). Some men deem as waste of semen and it undermines man’s pride as well as masculinity hence sexual related outcomes will always exist if this psychological mind-set is not washed away (Coast 2007). Condom use is a voluntary act where two or more people should have the same perception on their benefits (Marindo et al. 2003). The decision to distribute condoms in schools should be an inclusive one. In Zimbabwe, most policies have focused on child abuse, child marriages, rape cases and places little attention on safeguarding adolescents in sexual health behaviour where condoms have played a major role in prevention of spread STIs ad unwanted pregnancies (Mantula and Saloojee 2016).

There is great controversy about how people view the use of condoms in high schools (Masa and Chowa 2014). It has been reported by some scholars that some people belonging to some religious groups think that condom use results in promiscuity, irresponsibility and could not be advocated as policy to prevent HIV and AIDS (Masa and Chowa 2014). They view usage of condoms and their distribution at school as an incentive to encourage adolescents to indulge in sexual activities early (Masa and Chowa 2014). Also some people think that the virus could easily pass through the condom (Fallon 2008). However scientific evidence highlights that condoms are not manufactured with netting or holes that allow viral passage (Cates 2001; Holmes et al. 2004). Understanding perceptions of key stakeholders who are involved or could influence adolescents knowledge, attitudes and practices towards usage of condoms is key if adolescent sexual health outcomes are to be improved. Little is known about perception of adolescents and parents on condom distribution programme in secondary schools in Zimbabwean context and has not been investigated in Bulawayo Metropolitan Province. This study therefore sought to assess adolescents and parents perceptions towards condom distribution in secondary schools in the high density suburbs in Bulawayo.

Methods

Study Area

The study was conducted in three secondary schools in Bulawayo Province. We were granted permission to conduct our research in these three schools by the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education. Bulawayo is the second largest city in Zimbabwe after the capital city Harare. The city was awarded a Metropolitan Province status in 2013. Adolescent population in the city is estimated at 186,265 females and 182,330 males (Care 2016). Bulawayo has 41 registered secondary schools. The map showing the study area and the selected schools is presented as Fig. 1.

Study Design

A concurrent mixed method survey that utilised a questionnaire which had both quantitative and qualitative questions was used. This design enabled for specific variables (demographics, level of knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and practices) to be explored concurrently (Malina et al. 2011; O’Byrne 2007). This also provided knowledge and attitudes to be assessed quantitatively through utilisation of a Likert scale, whilst beliefs and practices were assessed qualitatively. It is worth noting that each and every individual have different beliefs and practices (that might need to be well understood through in-depth explanations in an open ended manner) that might be missed out if the data is to be collected quantitatively through a use of a structured questionnaire (Malina et al. 2011). It was therefore, appropriate for this research to utilise a mixed method approach so as to get a comprehensive overview of probed variables of interest (Malina et al. 2011; O’Byrne 2007).

Target Population

The target population were all adolescents aged 15–18 years who were attending secondary schooling at the selected schools (these were 2311 in total) and all parents/guardians who had adolescents in these selected schools and stayed within one kilometre radius. A one kilometre buffer was established on the map using QGIS and this is shown on Fig. 1.

Sampling

Sampling of Schools

The 3 schools out 41 were purposively selected as they were the only beneficiaries of the condom allocation and distribution program that was spearheaded by a Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO) at the time of data collection. The program was yet to be expanded to other schools by the time of data collection. Therefore this research only focus on the schools that had benefitted from the NGO program at the time of data collection and were already distributing condoms to adolescents. The geographic location of the selected schools are shown on Fig. 1.

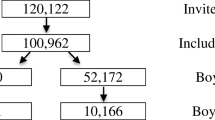

Sampling of Adolescents

About 100 adolescents were selected from each school as this number was above the minimum sample size calculated at 95% Confidence Level, 10% Width of Confidence and 50% expected Value of Attribute (241). This number was rounded off to 300 so as to improve the response rate. The respondents were selected through use of random numbers generated from class registers during school hours. This is summarised on Table 1.

Sampling of Parents

Since it was difficult to estimate the total number of parents/guardians who stayed within the 1 km radius and had adolescents in the participating schools, R38 sample size calculator on EPI INFO was used to determine the sample using 90% CI, 5% width of confidence and 50% expected value of attribute. This gave a sample size of 271 that was rounded of to 300. In recruiting these participants, researchers went door to door to houses that were within the 1 km radius and recruited the parent or guardian who met the inclusion criteria. This was repeated until 100 participants were obtained with respect to the participating school giving a total of 300. This is also summarised in Table 1.

Data Collection Tools

A researcher administered questionnaire with both quantitative and qualitative questions was used to collect data. The questionnaire was divided into 4 sections (demographic characteristics, level of knowledge, attitude, beliefs and practices), level of knowledge and attitudes were probed quantitatively whilst beliefs and practices qualitatively. The questionnaire was translated into isiNdebele which is the main local language spoken and taught in schools in Bulawayo. The questionnaire took approximately 15–30 min to administer.

Data Analysis

Knowledge and attitudes were assessed using adapted Likert scales from other authors (Allen and Seaman 2007; Boone and Boone 2012). The reliability of these Likert scales was also tested using the Crobanch’s alpha (Gliem and Gliem 2003). Ten questions were asked (to probe separately attitudes and knowledge levels of parents and adolescents on condoms) and scored with a correct response scoring a 1 and a wrong or bad attitude answer scoring a 0. These were aggregated and if the respondent gets 0–5 they were deemed Not Knowledgeable or they denoted bad attitude. Anyone scoring 6 and above were deemed Knowledgeable and or had Good Attitudes in the separate sections of knowledge and attitude. Attitude and knowledge outcomes were then cross tabulated with different demographic characteristics to determine associations using χ2 tests. Odds ratios with a 95% Confidence Interval (CI) were also used to determine associations with these different demographic characteristics with attitudes and knowledge. This was done using Multiple Logistic Regression (MLR). Thematic analysis was done on qualitative data obtained from beliefs and practices of adolescents and parents/guardians towards condom distribution in schools. This was done on MAXQDA Version 18.

Results

A total of 300 adolescents responded to the questionnaire whilst 243 parents/guardians responded to the questionnaire. This gave a 100% and 81% response rate in adolescents and parents/guardians respectively.

Demographic Characteristics

Females were more than males in both groups (56% in adolescents and 60% in parents/guardians). Majority (222, 91%) of the parents/guardians had attained at least Ordinary level of education. Majority of Parents/guardians (151, 62%) who responded to this survey had a partner. Employment status of the parents stood at 51%. These findings are presented in Table 2.

Knowledge on Condom Usage and Prevention of Pregnancies and Spread of Sexually Transmitted Infections

Parents/Guardians

About 60% of the parents/guardians were knowledgeable on condom utilisation and its associations with teenage pregnancy and prevention of spread of STIs. “Gender” and “Nature of employment” were not associated with level of knowledge regarding condoms and their distribution, use and prevention of pregnancies and spread of STIs. On the other hand age, religion and number of school going adolescents and parent/guardian has were significantly associated with level of knowledge regarding condoms. The findings are presented in Table 3.

Adolescents

About 67% of adolescent were knowledgeable on condom utilisation and its associations with teenage pregnancy and prevention of spread of STIs. Gender was the only variable that was not significantly associated with level of knowledge. Age was strongly associated with knowledge the older the adolescent the higher the chances that they were knowledgeable, for instance, older adolescents were 102 times more likely to be knowledgeable as compared to adolescents who were aged 15. These findings are presented in Table 4.

Attitudes Towards Condom Distribution at Schools

Parents/Guardians

About 72% of the parents/guardians had a good attitude towards condom distribution in schools. Age was associated with attitude using χ2P value; however, Multiple Logistic Regression revealed no difference between the different categories of age and how they influence attitudes. Religion showed a strong significance in influencing good attitudes with Catholics 227 times more likely to exhibit good attitudes as compared to Apostolic sect parents/guardians. These results are presented in Table 5.

Adolescents

About 27% of the adolescents had a good attitude towards condom distribution in schools. Gender was not significantly associated with attitudes. Age and level of education were significant contributors to good attitude with older, and adolescents in higher classes being 2.6 times more likely to exhibit good attitudes as compared to form ones. These findings are presented in Table 6.

Beliefs Associated with Condom Distribution and Usage by Adolescents

Beliefs associated with condoms distribution and usage by adolescents. Themes that emerged under this section were culture, age, STIs and many more. These themes and how they shape beliefs is explained in depth in Table 7. It should be noted that these themes were combined for both adolescents and parents.

Practices Associated with Condoms

Adolescents cited that they end up having unprotected sex as most condoms are very big. This theme together with others are presented in-depth in Table 8.

Discussion

Level of Knowledge

Adolescents were more knowledgeable than parents/guardians regarding condom usage and minimization of chances of pregnancies and spread of STIs. These findings are similar to findings obtained in studies that were conducted by different authors that found an association between educational programs that are conducted on adolescents and the subsequent awareness on condoms and their usage (Kegeles et al. 1988; Shoop and Davidson 1994). The studies further highlight that adolescents are more knowledgeable than their parents because they are exposed to sexual curriculum during their studies (Shoop and Davidson 1994).

We noted that the level of knowledge of adolescents towards condom use and spread of STIs increased with age. That is, as adolescents grow the more knowledgeable they become about sexual health issues in general. This is supported by studies conducted by different authors in different settings that as adolescents grow they are exposed to a plethora of information on sexual health in general from peers, parents and the school curriculum (Bankole et al. 2007; Clark et al. 2002; Dell et al. 2000). As they grow they mature and get to understand issues regarding sexual health better (Bankole et al. 2007). Studies further suggest that adolescents with parents/guardians that are knowledgeable on sexual health issues are likely to be knowledgeable as well about sexual health including usage of condoms (de Graaf et al. 2010).

It is worth noting that in our study parents who had three or more adolescents were more likely to be knowledgeable when compared to those with only one. It is explained in other studies that parents also learn from their children through experience in bringing them up (de Graaf et al. 2010). Having more than one adolescent would, therefore, mean more exposure and information seeking for the parent or guardian to bring up those adolescents.

Attitudes

Parents/guardians had better attitudes as compared to adolescents with most parents/guardians (over 70%) having a good attitude towards condom distribution at schools as compared to adolescents (just above 25%). Studies have found that adolescents do not use condoms consistently as they claim that these disturb their sexual experiences (Schaalma et al. 1993). This is also well supported by the themes from this study where adolescents found condoms to be too big and not fitting very well with their small organs. There was a similar pattern as that noted on the knowledge section showing that parents with three or more school going adolescents exhibited good attitude towards condom distribution at schools. Parents usually want the best for their children and would support any initiative that protects their children from STIs and pregnancy as this disturbs their schooling activities (Bankole et al. 2007). Religion also had an influence on the attitudes with those in the Catholic sects having 227 times more likely to be knowledgeable compared to those attending the Apostolic sects. In Zimbabwe, the apostolic sect does not believe in modern medicine and the strategies associated with it (Kambarami 2006; Mpofu et al. 2011; Tachiweyika et al. 2011). This, therefore, leads to members attending this sect having worse health outcomes, compared to members of the other sects (Mpofu et al. 2011). On the other hand Catholic sects have a lot of resources and programs that are targeted for the young particularly on sexually related issues (McKay et al. 2014).

Beliefs

Parents/guardians believe that condoms are associated with the European culture and this violates African cultural beliefs. Culture plays an important role in shaping up beliefs that in turn translate into practices (Lancaster and Di Leonardo 1997). Most parents believe that condoms promote promiscuity and they will instead reprimand their children and discourage them from engaging in sexual practices (Dahl et al. 2005; Lancaster and Di Leonardo 1997). Most religious sects discourage early engagement in sexual activities, thus leaving less opportunities for parents and adolescents to dialogue (Garner 2000; Hounton et al. 2005). This study concurs with our findings that showed that some sects such as the apostolic did not have good attitudes towards condom distribution at schools and their usage.

Practices

It was evident from the themes that emerged, to infer that most adolescents do not consistently use condoms even though there are distributed free of charge even in schools. Adolescents claimed that usage of condoms delays sexual intercourse especially if one has to engage in sexual activities frequently in a particular day. Difficulties associated with consistent condom use are cited by some authors as: difficulties in accessing condoms due to stigmatisation, shyness, communication with sexual partners and influence of HIV and AIDS with those already infected neglecting condom usage (DiClemente 1991; Schaalma et al. 1993).

Conclusion

Knowledge of condom use among adolescents in this study does not translate to good attitudes of regular, consistence and correct use of condoms. Adolescents had negative attitudes towards condom distribution in schools as they believed it ruins their sexual experiences. There is need for massive awareness campaigns to change their attitudes and embrace the condom distribution programs. This can potentially enable the adolescents to adopt safe sexual practices. Adolescents are the adults of tomorrow, and this subject of condom utilisation should be treated as a driver to a healthy population.

References

Allen, I. E., & Seaman, C. A. (2007). Likert scales and data analyses. Quality Progress,40(7), 64–65.

Bankole, A., Biddlecom, A., Guiella, G., Singh, S., & Zulu, E. (2007). Sexual behavior, knowledge and information sources of very young adolescents in four sub-Saharan African countries. African Journal of Reproductive Health,11(3), 28.

Boohene, E., Tsodzai, J., Hardee-Cleaveland, K., Weir, S., & Janowitz, B. (1991). Fertility and contraceptive use among young adults in Harare, Zimbabwe. Studies in Family Planning,22(4), 264–271.

Boone, H. N., & Boone, D. A. (2012). Analyzing likert data. Journal of Extension,50(2), 1–5.

Care, M. O. H. A. C. (2016). Zimbabwe National Adolescent Fertility Study, Harare.

Castrì, L., Tofanelli, S., Garagnani, P., Bini, C., Fosella, X., Pelotti, S., et al. (2009). mtDNA variability in two Bantu-speaking populations (Shona and Hutu) from Eastern Africa: Implications for peopling and migration patterns in sub-Saharan Africa. American Journal of Physical Anthropology,140(2), 302–311. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.21070.

Cates, W., Jr. (2001). The NIH condom report: The glass is 90% full. Family Planning Perspectives,33(5), 231.

Clark, L. R., Jackson, M., & Allen-Taylor, L. (2002). Adolescent knowledge about sexually transmitted diseases. Sexually Transmitted Diseases,29(8), 436–443.

Coast, E. (2007). Wasting semen: Context and condom use among the Maasai. Culture, Health & Sexuality,9(4), 387–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050701208474.

Dahl, D. W., Darke, P. R., Gorn, G. J., & Weinberg, C. B. (2005). Promiscuous or Confident? Attitudinal Ambivalence Toward Condom Purchase 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology,35(4), 869–887.

de Graaf, H., Vanwesenbeeck, I., Woertman, L., Keijsers, L., Meijer, S., & Meeus, W. (2010). Parental support and knowledge and adolescents’ sexual health: Testing two mediational models in a national Dutch sample. Journal of Youth and Adolescence,39(2), 189–198.

Dell, D. L., Chen, H., Ahmad, F., & Stewart, D. E. (2000). Knowledge about human papillomavirus among adolescents. Obstetrics and Gynecology,96(5), 653–656.

DiClemente, R. J. (1991). Predictors of HIV-preventive sexual behavior in a high-risk adolescent population: The influence of perceived peer norms and sexual communication on incarcerated adolescents’ consistent use of condoms. Journal of Adolescent Health,12(5), 385–390.

Fallon, D. (2008). Lets talk about sex. British Journal of Nursing (Mark Allen Publishing),17(20), 1260.

Garner, R. C. (2000). Safe sects? Dynamic religion and AIDS in South Africa. The Journal of Modern African Studies,38(1), 41–69.

Gliem, J. A., & Gliem, R. R. (2003). Calculating, interpreting, and reporting Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for Likert-type scales.

Grace, K. M. (1995). After more than a decade, still no AIDS cure. Alberta Report/Newsmagazine,22(4), 42.

Griggs, D., Nilsson, M., Stevance, A., & McCollum, D. (2017). A guide to SDG interactions: from science to implementation. International Council for Science, Paris.

Holmes, K. K., Levine, R., & Weaver, M. (2004). Effectiveness of condoms in preventing sexually transmitted infections. Bulletin of the World Health Organization,82(6), 454–461.

Hounton, S. H., Carabin, H., & Henderson, N. J. (2005). Towards an understanding of barriers to condom use in rural Benin using the Health Belief Model: A cross sectional survey. BMC Public Health,5(1), 8.

Kambarami, M. (2006). Femininity, sexuality and culture: Patriarchy and female subordination in Zimbabwe. South Africa: ARSRC.

Kegeles, S. M., Adler, N. E., & Irwin, C. E., Jr. (1988). Sexually active adolescents and condoms: changes over 1 year in knowledge, attitudes and use. American Journal of Public Health,78(4), 460–461.

Lancaster, R. N., & Di Leonardo, M. (1997). The gender/sexuality reader: Culture, history, political economy. New York: Psychology Press.

Luke, N., & Kurz, K. (2002). Cross-generational and transactional sexual relations in sub-Saharan Africa. Washington: International Center for Research on Women (ICRW).

Malina, M. A., Nørreklit, H. S., & Selto, F. H. (2011). Lessons learned: Advantages and disadvantages of mixed method research. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management,8(1), 59–71.

Mantula, F., & Saloojee, H. (2016). Child sexual abuse in Zimbabwe. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse,25(8), 866. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2016.1234533.

Marindo, R., Pearson, S., & Casterline, J. (2003). woRKING condom use and abstinence among unmarried young People in Zimbabwe: Which Strategy, Whose Agenda?

Masa, R. D., & Chowa, G. A. (2014). HIV risk among young Ghanaians in high school: Validation of a multidimensional attitude towards condom use scale. International Journal of Adolescence & Youth,19(4), 444–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2014.963629.

McKay, A., Byers, E. S., Voyer, S. D., Humphreys, T. P., & Markham, C. (2014). Ontario parents’ opinions and attitudes towards sexual health education in the schools. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality,23(3), 159–166.

Moore, S., & Rosenthal, D. (1991). Adolescents’ perceptions of friends’ and parents’ attitudes to sex and sexual risk-taking. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology,1(3), 189–200.

Mpofu, E., Dune, T. M., Hallfors, D. D., Mapfumo, J., Mutepfa, M. M., & January, J. (2011). Apostolic faith church organization contexts for health and wellbeing in women and children. Ethnicity & Health,16(6), 551–566.

O’Byrne, P. (2007). The advantages and disadvantages of mixing methods: An analysis of combining traditional and autoethnographic approaches. Qualitative Health Research,17(10), 1381–1391.

Pequegnat, W., & Bray, J. H. (1997). Families and HIV/AIDS: Introduction to the special section. Journal of Family Psychology,11(1), 3–10.

Pradhan, P., Costa, L., Rybski, D., Lucht, W., & Kropp, J. P. (2017). A systematic study of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) interactions. Earth’s Future,5(11), 1169–1179.

Rumano, M. B. (2009). Africa University’s approach to Zimbabwe’s HIV/AIDS epidemic: A case study of teacher preparation. (text). Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ddu&AN=5260F1F52B7C891D&site=ehost-live. EBSCOhost ddu database.

Schaalma, H., Kok, G., & Peters, L. (1993). Determinants of consistent condom use by adolescents: The impact of experience of sexual intercourse. Health Education Research,8(2), 255–269.

Shoop, D. M., & Davidson, P. M. (1994). AIDS and adolescents: The relation of parent and partner communication to adolescent condom use. Journal of Adolescence,17(2), 137–148.

Smith, M. K. (2002). Gender, poverty, and intergenerational vulnerability to HIV/AIDS. Gender & Development,10(3), 63–70.

Stanton, B., Bo, W., Deveaux, L., Lunn, S., Rolle, G., Xiaoming, L., et al. (2015). Assessing the effects of a complementary parent intervention and prior exposure to a preadolescent program of HIV risk reduction for mid-adolescents. American Journal of Public Health,105(3), 575–583. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302345.

Tachiweyika, E., Gombe, N., Shambira, G., Chadambuka, A., Tshimamga, M., & Zizhou, S. (2011). Determinants of perinatal mortality in Marondera district, Mashonaland East Province of Zimbabwe, 2009: A case control study. Pan African Medical Journal,8(1), 7.

Trinh, T., Steckler, A., Ngo, A., & Ratliff, E. (2009). Parent communication about sexual issues with adolescents in Vietnam: Content, contexts, and barriers. Sex Education,9(4), 371–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681810903264819.

United Nations. (2000). The United Nations on the Demographic Impact of the AIDS Epidemic. Population & Development Review,26(3), 629–633.

Funding

The research was not funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NM conceptualised the research idea. The author also collected and analysed qualitative data. WNN refined the idea and together with NM drafted the manuscript. The author also co-ordinated the manuscript writing process. BN developed quantitative data analysis plan, cleaned and coded the raw data and performed data analysis. NK collected data and developed the map for the study area and proof read the manuscript. OD designed the methodology and data collection tools. The author also translated the data collection tool to Local language (Ndebele). All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

Written permission to carry out this study was sought from the Department of Environmental Science and Health at the National University of Science and Technology and from National AIDS Council (Bulawayo) and the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education for Bulawayo Metropolitan Province. Written consent was obtained from all parents and legal guardians. With regards to adolescents permission was first sought from their parents or legal guardians and the adolescents’ themselves accented to participate.

Informed Consent

All respondents were made aware that their participation was voluntary and they could opt out of the study at any given time without any explanation. Participants were not coerced or given tokens of appreciation for being part of the study. The questionnaires were translated into local language (Ndebele) that participants understood so as for them to understand and participate fully in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Mudonhi, N., Nunu, W.N., Ndlovu, B. et al. Adolescents and Parents’ Perceptions of Condom Distribution in Selected Secondary Schools in the High Density Suburbs of Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. Sexuality & Culture 24, 485–503 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-019-09642-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-019-09642-2