Abstract

Since its inception, public deliberation has been largely seen as an effective tool of inclusion and transformation within democratic politics. However, this article argues that public deliberation is not necessarily inclusive and transformative. These aspirations can only be achieved if certain conditions are met. The qualitative analyses drawn upon in this public deliberation study included virtual and face-to-face conversations between participants (N = 70) about opinions on eating together. The article examines factors that can impede food system transformation initiatives. This can be particularly problematic in low- and middle-income countries because corruptibility can reduce the stringency of food system transformation policy. This study was conducted with participants from the Dutch cities of Almere and Amsterdam. The article argues that public deliberation can be truly transformative when (1) it is institutionally sanctioned, and (2) participants in the deliberation are given more time to make their arguments and reconsider these arguments in light of what others have to say.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

What Is Deliberation and How Did It Come About?

Public deliberation is an approach in democracy based on the idea that those affected by or interested in a collective decision have the right, opportunity and capacity to participate in consequential deliberation about the content of decisions (Ercan et al., 2019). Public deliberation illustrates that democracy has demands that transcend the ballot box (Sen, 2003). This broader approach to democracy, through public deliberation, offers citizens the opportunity to participate in political discussions and, in doing so, be in a position to influence public choice. This process of decision-making through public deliberation can enhance information about society and individual priorities. The process of public deliberation can include simple expression, listening and reflection, and decision-making (Ercan et al., 2019). But it is the reflective function that differentiates deliberation from mere talk.

The idea of public deliberation draws its origin from classic Greek democratic ideology. For instance, Aristotle conceived the democratic process as a considered judgement of what seems right or wrong (true or false), an exchange of points of view about reasons for a particular choice, a rational process of acquisition of information and a clarification of one’s preferences based on this new information (see Bachtiger et al., 2018). These ideas inspired the founding fathers of the United States Constitution, through a process of reconciling perspectivesFootnote 1 on the political practice of self-determination (Bessette, 1994). The Greek democratic ideology also inspired contemporary scholars (such as Manin, 1987; Cohen, 2009) in setting out a new theoretical model around public deliberation. This phase included identifying alternative paradigms which could influence the form of public deliberation. More recently, there has been a move from the theoretical phase of public deliberation to a more empirical phase. This transition is the expression of deliberative democracy in the forms of mini-publics,Footnote 2 constitutional courts and legislatures both in open and closed sessions (Setälä, 2014).

Whilst ancient Greece has often been credited for its contribution to democracy, Greeks were not unique in this respect. It was noted by Sen (2003) that there is an extensive history of the cultivation of tolerance, pluralism and public deliberation in other societies. Although people in different cultures may not use the word deliberation to describe the pros, cons and trade-offs of different options, decisions based on alternative courses of action have often been made by communities across the world (Marin, 2006). This suggests that although mainstream deliberation research has been conducted in predominantly Western cultural contexts (see Min, 2014), deliberation is not a purely Western construct. For instance, Sen (2003) argues that deliberation is a universal practice, and deliberative democracy has global roots. According to Sen, the ability to deliberate, to collaborate with others and to engage in public argumentation is in fact basic human nature.

Usefulness of Public Deliberation

The ultimate purpose of convening a public deliberation exercise is open-ended. It can even be to answer a research question but is more commonly to inform or exert some influence on public policy. Deliberation requires a process of mutual justification where participants are offered reasons for their positions, listen to the views of others and reconsider their preferences in light of new information and arguments (Ercan et al., 2019). Self-expression can contribute to democracy only if it is linked with listening and reflection. In general, public deliberation has been presented as giving agency and a voice to citizens, thus improving their interactions with decision-makers and making citizens more knowledgeable about the content, trade-offs and challenges of public policies (Barrett et al., 2012). It also helps decision-makers to better understand citizens’ needs, interests, concerns and values, thus shaping the way they, the leaders, approach decision-making (Munno & Nabatchi, 2020). These benefits of public deliberation have tended to emphasise the transformative potential of public deliberation. It has long been established that when deliberation is done right, it regularly changes the opinions of participants (Fishkin 2009; Himmelroos & Christensen, 2014). This has been called preference transformation (Dryzek & Lo, 2015). Through its principles of inclusiveness and unconstrained dialogue, public deliberation is expected to encourage people to understand the judgements of others and, most importantly, to reflect on and potentially transform or change their own assumptions and values (Blue & Dale, 2020). In other words, the outcome of deliberation is often an expected exchange of position—people weighing what they hear and possibly changing their position in response (Jennstål & Niemeyer, 2014).

Alternative Views on Deliberation

Although public deliberation research has been strongly associated with democracy and transforming opinions, there are contrasting examples of public deliberation in ‘non-democratic’ spheres (see Medaglia & Zhu, 2017; Filatova et al., 2019). These have been collectively described as authoritarian deliberation (He & Warren, 2011) and include deliberation ranging from spaces created and totally controlled by governments to grassroot deliberation practices which are monitored by governments. This corroborates another line of thinking which contests the link between deliberation and democracy (Baiocchi & Ganuza, 2017). For instance, such sceptics of deliberation have argued that despite best intentions, the new spaces created for deliberation, even in ‘democratic’ societies, tend to reinforce, instead of challenge, existing inequalities and power relations (Morozov, 2011). Others argue that the multiplicity of communication spaces where participants are encouraged to voice their opinions exacerbates fragmentation in the public sphere by hindering ‘opportunities for linking together political struggles’, thus the formation of strong ‘counter-hegemonies’ (Dean, 2015: 52F). Others such as Sunstein (2017) warn of polarisation and the loss of common public life as people gravitate to enclaves where their views can or are reinforced in interactions with like-minded others and driven to extremes.

How Can Public Deliberation Be Improved?

The lesson to be learned is that deliberation is not implicitly democratic or transformative. Certain conditions have to be met in order to enhance the transformative potential that resides in deliberation. Furthermore, although the recent empirical turn in studies on public deliberation helps to clarify the institutional conditions under which good-quality deliberation might be enabled, a criticism is that the analysis often prioritises isolated instances of deliberation, investigated with little if any attention to their relationship to the spatial system as a whole (Owen & Smith, 2015).

Scholars such as Benhabib (1992) and Calhoun (1992) have drawn particular attention to the continued importance of the need for public space as a necessary condition for deliberative democracy. Their key question which is restated by other contemporary scholars is, how to create such spaces in the absence of formal structures created by government policy? Public deliberation occurs within and across multiple and diverse spaces (Elstub et al., 2016) and times (Kraeger & Schecter, 2020) of engagement. This means that deliberation offers the space for people to explore and examine alternative frames of an issue, and to confront each other with rival worldviews, competing ideals and conflicting political commitments (Blue & Dale, 2020). However, finding the right time and place for reflection has become increasingly more challenging in contemporary societies (Ercan et al., 2019). This is because spaces for deliberation are not adequately designed to enable participants to listen to each other and to develop thoughtful new conclusions together (Kraeger & Schecter, 2020). Also, spaces for deliberation often do not offer participants enough time to explore topics in-depth (Kraeger & Schecter, 2020). Despite these strictures, there has been little empirical research examining how in practice prospective public deliberative processes should be organised in space and time to initiate change (Bourgeois et al., 2017; Lehoux et al., 2020). The aim of this paper is to generate methodological insights into the ways deliberation can stimulate people’s opinions regarding what is right or wrong and what should be done to make things better. This paper will seek to address this objective by building on two key concepts: heterotopia and discursive distancing.

Spaces for Deliberation as Friction Spaces

Foucault’s concept of heterotopia presents a critical groundwork for developing interdisciplinary understandings of the complex nature of twenty-first-century space. It also helps us to understand sociocultural and economic differences and identities in multicultural and multivalued settings. The concept of heterotopia was first introduced in the preface of Foucault’s (1966) work Les Mots et les choses (translated into English in 1970 as The Order of Things). In a lecture titled ‘Of Other Spaces’, Foucault (1967) elaborated on the concept. He described heterotopia as a space that disrupts the continuity and normality of common everyday places by breaking down boundaries within and between places into spaces of ‘otherness’ (des espaces autres). He stated that:

A society, as its history unfolds, can make an existing heterotopia function in a very different fashion; for each heterotopia has a precise and determined function within a society and the same heterotopia can, according to the synchrony of the culture in which it occurs, have one function or another (Foucault, 1967: p. 26).

Foucault observed the heterogenous and hierarchical nature of spaces. He stated that heterotopias merge certain spaces, like ‘private space and public space, family space and social space, cultural space and useful space, the space of leisure and that of work into spaces of otherness’ (Foucault, 1967: p. 23). He noted that there are spaces where things find themselves because they had been violently displaced. There are also spaces where things exist naturally and in a stable atmosphere (Foucault, 2006). These divergent spaces do not exist in isolation. There is a network of multiple dialectical relationships in which one space influences others and is influenced by others. Heterotopia presents spaces that represent incompatibility and reveal paradoxes in ideas, values and knowledge in general.

This incompatibility is what distinguishes Foucault’s heterotopia from the classic concept of utopia. In its classic sense, utopia is based on the construction of imaginary worlds which are free from the difficulties that beset us in reality. Although this dream of a life without complications is seen by some critics of utopia as unrealistic, other supporters of the concept see utopia as a vision to be pursued and not a vision that could necessarily come true (Levitas, 2013). Foucault’s heterotopia does not present a utopic view of society in which different ideas, values and knowledge exist devoid of friction or complication. He presents heterotopia as spaces of friction in which ideas and values compete against each other in defining what truth is or should be. He interprets heterotopia in such a way that we can see this fragmented realm as one of opportunities and freedoms, as one in which otherness or difference in opinion becomes a real possibility and opportunity.

According to Foucault (2006), space constitutes the form of relations amongst sites, or is defined by relations between points or elements. The homogeneity or interrelation of elements in certain spaces (or places) changes significantly over time. Relating time and space, Foucault and Miskowiec (1986) note that every experience of interaction between people cannot disregard the interaction of time with space. In his work ‘Of Other Spaces’, Foucault’s fourth principle entails that ‘heterotopias are most often linked to slices in time, often breaking with traditional time in certain spaces’ (Foucault, 1967: p. 27). For instance, time does not have to be finite as in a certain hour of the clock (where time begins and ends at a particular spot on the clock). Museums or libraries view time in a more infinite manner in which an end of time is not conceived.

Foucault’s theoretical framing of heterotopia as spaces in which otherness or differences converge does not proceed to state what happens when these alternative ideas, visions and knowledges converge. Although Foucault’s heterotopia can be seen as overly optimistic because it suggests that a heterotopic can always have room for pluriformity (in values and opinions), it is unclear how differing opinions can be perceived by others or what effect otherness can have on the views held by others. Can others tolerate other views in a deliberative heterotopia? Can others be influenced by others’ views in a deliberative heterotopia? To answer such questions, this paper also draws on David Shane’s (2005) interpretation of heterotopia. He uses Foucault’s concept of heterotopia to articulate how urban systems and fragments change in contemporary cities as citizens interact with others. He identifies heterotopias as particular places where processes of change and hybridization are facilitated. Based on this conception, this paper views spaces for deliberation as particular spaces where change and hybridization are facilitated through the pluriformity of values and meanings.

There is the need to examine spaces of deliberation for elements which can exclude or include participants in the process. In other words, spaces of deliberation can be loaded with unequal power relations. Therefore, it is important to broaden the typology of spaces of deliberation to see what works and what doesn’t work for certain groups in society. Having presented heterotopias as spaces where change could occur, it is important to look at what forms this change could take.

Additional Factors Shaping Public Deliberation

Based on a review of the existing literature, we can further elaborate key factors associated with public deliberation. They include the following.

Compromise

For some scholars, the dilemmas of compromise are of primary importance. By engaging in public deliberation exercise, people can become more willing to tolerate others. According to Polletta (2020), reaching a compromise implies not only that people have altered their opinions, but that they are willing to endorse opinions that run contrary to their own interests. Polletta adds that the person who makes a compromise could be seen as cooperative and strategic (positive attributes). The point of caution with compromise in deliberation is that participants could mistakenly believe a problem has been solved when others choose to compromise. Therefore, a compromise is not necessarily a solution to a problem. Another danger is that participants may be forced to compromise in order to avoid confrontation with more powerful actors. Thus, compromise in this case is merely to avoid confrontation and not based on conviction.

Awareness

Here, the expected outcome is that engaging in discussion with others can offer new insight and information (Polletta, 2020; Blacksher et al., 2021; Ghimire et al., 2021). In Pitts et al. (2020), participants reported that through the discussion, they became aware of new arguments and gained insight from other participants. Intersubjective rationality is ‘when individuals who agree on preferences also concur on the relevant reasons, and vice versa for disagreement’ (Niemeyer & Dryzek, 2007: p. 500). Intersubjective rationality is an important outcome of public deliberation since it allows for normative criteria to be applied to decisions, without having to designate particular decisions as ‘right’ or ‘wrong’.

Shift in Opinion

This is potentially the most ideal outcome of public deliberation (Goold et al., 2012; Himmelroos & Christensen, 2014; Polletta, 2020; Blacksher et al., 2021; Ghimire et al., 2021). Here, one of the most prevalent arguments is that deliberation ‘… tends to change things–opinions, rationales, intensity, attitudes toward opposing views, and so on and often aims to influence policy’ (Goold et al., 2012: p. 24). In this regard, exposure to expert information from different perspectives and a process of listening to others can lead to changes in opinion about specific aspects of policy, both positive and negative (Stark et al., 2021).

Feeling of Equality or Equity

Equality and equity must also be considered desired outcomes of public deliberation (Abdullah et al., 2020; Blacksher et al., 2021; Ghimire et al., 2021). Research suggests that opportunities for deliberation amongst ordinary citizens can greatly enhance their confidence regarding their own ability to participate in conversations surrounding critical issues (Stirling, 2008). The historically marginalised are often drawn to deliberative exercise (Abdullah et al., 2020). It is important that they leave the deliberation process with the feeling that they were treated fairly and that their voices were heard. This poses a challenge to the public deliberation process to ensure that policies developed through deliberation are equal or equitable. Regarding this, Karpowitz and Raphael (2020) argue that public deliberation recruitment practices should include and empower all perspectives in society—not necessarily strictly representative samples. However, Coelho and Waisbich (2020) caution here that satisfying equity and equality amongst participants is not simply a function of the quality of the deliberative process. Rather, they argue that addressing inequality requires attention to other elements of the political setting that go beyond deliberation, such as the array of political alliances and broader patterns of mobilisation (Coelho & Waisbich, 2020).

Confirmation of Pre-existing Perspectives

Being exposed to a variety of perspectives can also ensure that people’s own opinions are well informed. Even without changing their views, participants can still gain deeper insight into their own views, and that in itself is change. Regardless of what evidence people are presented, they evaluate new information in a way consistent with their prior beliefs and in turn, this biased assimilation strengthens the prior beliefs that give rise to the original bias (Sherman & Cohen, 2006). People often use their prior beliefs to evaluate the validity of incoming data. Likewise, people also tend to accept with little scrutiny information which conforms with their pre-existing beliefs (Nisbett & Ross, 1980). Just talking or listening to others is an important form of political or civic engagement that may advertently or inadvertently result in learning or a change of knowledge (Gordon & Baldwin-Philippi, 2014; Pitts et al., 2020), even if opinions do not change. That in itself is change. Goodin (2000) describes this process of deepening, affirming or reinforcing existing impressions as ‘deliberation within’. Deliberation within is a part of the deliberative process that entails taking in and considering multiple viewpoints, arguments and counter-arguments, but not necessarily voicing them or using them to alter the way one thinks. This too is a process of change.

Discursive Distancing and Outcomes of Heterotopia

How do opinions change? This paper argues that spaces can only produce the ideal situation of a shift in opinion when discursive distance between participants is not too wide. This introduces the concept of discursive distancing, which refers to a sort of ‘othering’, or the tendency to impose a strict distinction between we (our kind of people or values) and them (not our kind of people or not our kind of values), or between our acceptable view and their unacceptable view (Boréus, 2006: p. 410). This polarisation of views makes it harder for people to express certain ideas and perspectives or accommodate certain views and perspectives. Those who do not wish to pick sides or who show a predisposition to listen to what others have to say could feel ostracised for having a view associated with other unacceptable views. In political terms, such distinctions are analogous to the Left-wing and Right-wing dichotomy. Extreme discursive distancing means that an action can neither be justified nor understood, it can only be condemned. Spaces can either enhance these extreme views (increased discursive distance) or reduce them (diminished discursive distance). The assumption is that the deliberation process will more positive outcomes if spaces for deliberation diminish discursive distance. This paper will examine various deliberation spaces, identify what kind of changes are most prevalent in these spaces and link these changes to certain characteristics that either inhibited or enhance discursive distances.

How This Research Was Conducted from Theory to Practice

This section introduces the study area and explains how the data were collected. The methodological approach that guided this inquiry was reflexivity. In a deliberative process, the spaces that function primarily to gather and amplify voice (expressive function) should first be linked with the spaces that place an explicit emphasis on reflection and listening (reflective function). The premise is that participants engage in continuous examination and questioning of the assumptions and commitments that are presented as expressive functions (expression; see Stilgoe et al., 2013).

Study Area

The data for this study were collected in the Dutch cities of Almere and Amsterdam. Whilst Amsterdam is the largest city in the Netherlands, Almere, which is younger and smaller, requires a longer introduction. Almere is a newly planned and rapidly growing suburb, 30 kms east of Amsterdam (Jansma & Visser, 2011), making it an ideal suburban environment for commuting into Amsterdam (Dormans, 2008). The city was founded approximately 45 years ago on the reclaimed land of the Southern Flevopolder in the Ijsselmeer and is part of the Amsterdam Metropolitan Area (Jansma & Wertheim-Heck, 2021). The city grew to 64,000 inhabitants between 1976 and 1989 (Constandse, 1989). In 2019, the city had a population of approximately 208,000 inhabitants (Jansma & Wertheim-Heck, 2021), and this figure is expected to increase to 350,000 inhabitants by 2030; thus, it is on course to become the Netherlands’ fifth largest city. This rapid expansion in population is fuelled by the growing need for new housing in the Amsterdam Metropolitan Area and the absence of alternative locations for constructing new housing (Jansma & Visser, 2011). Although the city was originally designed to accommodate urban agriculture (Zalm & Oosterhoff, 2010), this was never fully implemented, with the only exception being the urban farming district of Oosterwold on the city’s Eastern fringe (Dekking et al., 2007). The Almere Principles (Feddes, 2008) for a sustainable future consist of the following seven starting points for sustainable urban development: cultivating diversity, connecting place and context, combining city and nature, anticipating change, continuing innovation, designing healthy systems and empowering people to make the city more liveable (Feddes, 2008).

Setting the Scene

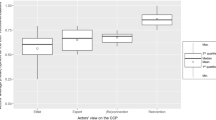

This study was based on a previous unpublished project by the author that sought to understand the visions of the residents of Almere concerning a healthier food future, for which it employed the photovoice method. Thirty-four participants were involved in the project, each of whom provided two photographs (N = 68 photos) to answer the following main question: How do you see a healthier food future for Almere? Residents (men, women, teenagers, elderly and people with different ethnic backgrounds) were asked to take photos of their daily lives that reflected their visions of a healthier food future. After the photographs were collected, one-on-one interviews were conducted with the participants, mostly using Zoom due to COVID-19 restrictions. The interviewees were asked to explain the following: (1) What is visible in the photos? (2) What motivated you to take the photo? (3) What is the meaning of the photo in line with visions of a healthier food future? Next, through a thematic analysis of the discussions that followed the presentation of the photographs, the frequency of common themes was summed and presented as percentages, as presented in Fig. 1.

According to this figure, cooking and eating together were the second most important themes in the residents’ visions for a healthier food future. Coincidentally, it was also the theme of the Dutch Food Week, which was held in Almere in October 2021. Farmers and horticulturists, (local) governments, inspiring food entrepreneurs and green educators came together and shared knowledge in various areas as well as demonstrated new developments related to food. The aim of the public deliberation was to initiate a change of opinion regarding healthy eating through an exchange of ideas in heterotopic spaces. What change this process could lead to was not defined. Therefore, all of the change outcomes presented in the conceptual framework sections of this paper were possible and expected outcomes.

In this study, three kinds of spaces of deliberation for change accommodated different views and opinions about what a healthy food practice is or should be. Noteworthily, the primary concern of this study was not to make a novel contribution to knowledge on healthy or unhealthy food practices. Food was used as a topic to generate discussions in the deliberation process because almost everyone can relate to food in some way. Everyone eats, and everyone knows how, where and what they want to eat. A viable context for large-scale public deliberation can be shaped as follows: first, the spaces for voice and expression should be accompanied by sufficient spaces for reflection and listening; and second, collective decisions should follow the sequence of expression, then listening and lastly reflection (Ercan et al., 2019). To illustrate the plausibility of the findings, this study employed the following methodological cases with spaces of listening, reflection and talk built into conventional democratic practices: face-to-face public (Almere city centre), online semipublic (with an institution of applied sciences in Amsterdam) and face-to-face semipublic (with an institution of applied sciences in Almere). Figure 2 presents the study sites.

In the face-to-face semipublic and face-to-face public cases, COVID-19 regulations were not strict at the time, and deliberation was conducted face-to-face as part of the events of Dutch Food Week (13th October 2021). In the online semipublic case, which took place on 23rd December 2021, stricter COVID-19 regulations had come into force in the Netherlands the week before the event, which forbade mass gatherings. Therefore, the deliberation was virtual through Microsoft Teams. Approximately 70 people participated in the deliberation process in all three deliberation spaces. These were subdivided as follows: Almere city centre (30 participants with more diverse demographic characteristics), a university of applied sciences in Almere (20 participants in face-to-face deliberation, predominantly involved students aged 18–30 years) and a university of applied sciences in Amsterdam (20 participants in virtual deliberation, predominantly involving students aged 18–30 years).

The Deliberation Process

In each case, participants were shown posters of what others had said concerning eating and cooking together as a healthy food practice. In response to these posters and the messages they carried, participants were asked to share how they felt or their impressions about the photos and the opinions expressed on them. There were 16 numbered posters in total, and some samples are presented in Fig. 3. In each case, the participants were also given the chance to respond to comments from other people. The online deliberation lasted for an hour. In the cases of face-to-face deliberation, the physical platform with the exhibition of posters was open for 3 h (3–6 pm in each case).

Requirements for Successful Deliberation

This section presents evidence from empirical data to either support or reject the assumption that certain heterotopias either enhance or limit discursive distance. The question of what it is in these heterotopic spaces that makes them enhance or reduce discursive distance can be answered according to the following two main factors: institutional norms (or a lack thereof) and time (duration of deliberation).

Institutional Norms or a Lack Thereof

The first two types of heterotopias are the online heterotopia of the school and the face-to-face heterotopia of the school, both of which are semipublic spaces. These comprise institutional spaces that can shape the process of change in highly controlled environments. In these spaces of highly disciplined order, relationships between participants are organisationally restructured to facilitate the emergence of a certain order that may transform society in a particular way. Loopmans (2002) defined institutional places (and by extension spaces in this paper, since the study included virtual spaces such as online communication space) as places in which access is formally regulated. To belong to a school, one must fulfil certain requirements. Being at a school also requires students to conform to certain norms and values that are set by the institution. If one of these norms is to promote or accept a particular understanding of what healthy eating practices are, then students will likely be more obliged to accept that vision of healthy eating as the standard.

Concerning the meanings of healthy and unhealthy food, these are understood to be either nutrition-based or socioculturally informed. Nutrition-based meanings of healthy food refer to the process of food medicalisation based on scientific nutritional rationality (Viana et al., 2017). In socioculturally informed meanings of healthy food or its practices, food–health practice associations are created in particular contexts by the social actors present there (Díaz-Méndez & Gómez-Benito, 2010). This involves assigning moral meanings to foods and is influenced by each social group’s cultural values (Gaspar & Larrea-Killinger, 2020). These socioculturally informed meanings of healthy food include the pleasure derived from the acts of sharing food experiences, which positively contribute to consumers’ overall pleasure and satisfaction with food consumption (Mendini et al., 2019).

In the Netherlands, the latest version of healthy food as promoted by the Wheel of Five (national guidelines on healthy food) of the Voedingscentrum (Netherlands Nutrition Centre) is largely nutrition-based. It is more focused on the prevention of chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases (Feskens, 2016). Therefore, the concept of the Wheel of Five is based on the latest scientific information regarding food products that are good and healthy for the human body. One could argue that this view of healthy food is being promoted by institutions of higher learning in the Netherlands. Therefore, presenting an alternative view to students of a healthy food practice being to eat with others (i.e. something that has nothing to do with nutrition) created a clash of values. This created a polarised state, or a sort of othering. This refers to a tendency for participants to view a strict distinction between our values (healthy eating as eating what is nutritionally healthy) and their values (healthy eating as eating socially with others), or between our acceptable view and their unacceptable view of healthy eating. In other words, a wide discursive distance existed between the students online and the views expressed on the posters, which promoted a socially constructed meaning of healthy eating practices. Students who participated in the online deliberation largely disagreed with the alternative views expressed on the posters. The following quotes from students from the online heterotopia of the school illustrate this discursive distance:

Referring to poster 14: This seems more like a healthy wishful thinking. Basically, they wish what they are eating and drinking could have been healthy. But it isn’t so they just make something up by saying that eating together is healthy. Hahahaha [sarcastic laughter]. All I see is them eating unhealthy food. It doesn’t matter how they try to coat it or defend what they are eating. It is unhealthy food, period. (Gina, Amsterdam Univ of Applied Sciences)

Referring to poster 14: I think these people do not have a good argument. In my opinion, they are just making up an excuse to be able to eat unhealthy food and drink beer which is also unhealthy without feeling guilty. (Ilse, Amsterdam Univ of Applied Sciences)

Referring to poster 14: I see beer is their priority there at the table ☺ That’s not a healthy food practice, is it? (NX, Amsterdam Univ of Applied Sciences)

Referring to poster 4: Someone is just lazy not being able to eat healthy and then they come up with this eating together at the table as healthy eating bull***t. (JSch, Amsterdam Univ of Applied Sciences)

In the semipublic face-to-face deliberation at the university in Almere, although participants met other participants face-to-face, the power of institutional norms could still be found in the majority of the opinions they shared. The following quotes demonstrate that although the students agreed with the views expressed on the posters to an extent, they still tended to lean on the institutionally sanctioned, nutrition-based understanding of healthy eating practices:

Referring to poster 14: Getting together and talking about life is very healthy I think, humans are very social animals after all. However, the alcohol is definitely not healthy food, although it feels good to drink ☺. (Daniel, Almere University of Applied Sciences)

Referring to poster 4: I agree that eating together is very healthy! But you can also eat healthy together. You don’t have to eat all this unhealthy food I see on the photo which they are branding as healthy by ‘eating together is healthy’. (Jose, Almere Univ. of Applied Sciences)

Referring to poster 14: Very studentesque with all the unhealthy things like beer and such. Seems like a nice relaxing get together though. (Jan, Almere Univ. of Applied Sciences)

As these quotes indicate, despite the institutional sanctioning of norms around what is understood to be healthy and unhealthy food, the discursive distance between the participants was smaller in the semipublic face-to-face deliberation than in the online deliberation. The students in the face-to-face deliberation were more willing to accommodate alternative views, even if their institutionally sanctioned views did not change. The key factor responsible for moderating this discursive distance was face-to-face contact. Face-to-face social interactions offer a higher quality of conversation by virtue of increased responsiveness and sensory engagement (Kvarnstrom, 2015). This implies that face-to-face communication allows for vital and complex nonverbal/nondiscursive communication in which nuances of emotion are conveyed through facial expressions and body language; thus, relationships and bonding are strengthened, willingness to share difficult emotions is increased, and social understanding is enhanced (Kvarnstrom, 2015). In the online deliberative process, the lack of face-to-face contact restricted the development of rapport, thus creating greater discursive distance between the participants.

The third heterotopia was that of the public space—namely the public square in Almere city centre. Shane (2005) asserted that such a heterotopia comprises realms of apparent chaos and creative, imaginative freedom. Here, expectations are loose, and the primary values are pleasure and leisure, consumption, and display, not work or study. Furthermore, institutional norms are non-existent, and people have more freedom to choose how they want to think or what they believe or say. This freedom from institutional expectations diminished the tendency for participants to view a strict distinction between our values (healthy eating as eating what is nutritionally healthy) and their values (healthy eating as eating socially with others), or between our acceptable view and their unacceptable view of healthy eating. Therefore, the discursive distance between the participants in the heterotopia of the public space was much smaller. Evidence of this is found in the following quotes, which demonstrate how participants were less critical of the views expressed on the posters:

Referring to poster 4: What you see on this poster is absolutely normal to me. Back home in India we often eat together as a family. During COVID-19 we even ate together more as we spent more time together at home. Everyone likes food made at home by their mothers and to me, eating together like this with family gives me that feeling. (23-year-old Indian resident of the Literatuurwijk neighbourhood of Almere)

Poster number 4 appeals to me. This is because I regularly have dinner at my parents’ place. There are often loads of snacks and drinks at the table. We normally do this as a family but sometimes with guests too. It is indeed something I find really enjoyable. (24-year-old resident of the Stedewijk neighbourhood)

[Referring to poster 13] I agree with this one as well. This reminds me of when I still lived with my parents and we used to eat in front of the television, and it was just so boring. Eating at a dinner table is much more gezelligFootnote 3! (SBr, resident of the Tussen de Vaart neighbourhood)

I agree and I find it important to eat slowly as they mention on poster 13. That is something I would consider doing more because it is healthy. That way I can also learn to control how much food I eat as they mention on the photo. I often don’t have enough time to eat. So, I end up eating a lot but that has to change. (Almere resident from the Filmwijk neighbourhood)

Time

Time was also observed to be a critical factor that influenced the discursive distance between participants in all three heterotopic spaces. Here, time refers to the duration of the deliberation process. In the case of the online school heterotopia, the deliberation process lasted only 1 h and involved 20 students. Assuming that every student had something to say and, due to the nature of the online platform, only one person could speak at a time, one can hypothetically state that each student only had approximately 3 min to speak. In the other two heterotopias (face-to-face school and public place), the deliberation process lasted 3 h. Following the aforementioned logic, this means that the face-to-face school space allowed each participant approximately 9 min to talk. The difference between face-to-face and online deliberations in terms of time is that in face-to-face deliberations, it is much more common and easier for several people to talk simultaneously in smaller groups. In the online deliberation, only one person spoke at a time. Thus, cumulatively, people in the face-to-face heterotopia had much more time to deliberate than those online.

Crucially, having more time translates to the ability to expand on answers, the time to think and, in the case of face-to-face interviews, the time to feel comfortable in the presence of certain people. Irvine (2011) found that nonphysical interviews were on average shorter than face-to-face ones because the participant spoke for less time. Thus, participants are unable to fully express themselves or genuinely understand what others are saying. Perhaps face-to-face interactions allow participants to talk more openly in the ‘real world’. With more time at their disposal, they feel more informal and relaxed, which would likely facilitate the disclosure of material that might be withheld in more formal or time-constrained settings (Hart & Crawford-Wright, 1999). Having more time to feel relaxed and a more informal feel in face-to-face deliberations could have also spurred this study’s participants to share their personal experiences with others. Using personal experiences when discussing a subject could be an easy and effective strategy for reducing discursive distance. It could start further conversations and help people to connect with the people around them—even if they are surrounded by others who do not share the same opinions. This study argued that in the public deliberation, it was crucial to provide sufficient time for people to use their personal experiences to inform their opinions about others or what others say. The findings have revealed that references to personal experiences and stories helped people to be more accommodating to other views, as empirical evidence in the previous section revealed (see the quotes from the face-to-face public and student heterotopias). In these cases, there were more references to personal experiences when people considered others’ viewpoints in face-to-face deliberations with other participants.

Major Takeaways from This Study

The normative stand adopted in this study was that positive outcomes of public deliberation are more likely to be observed when deliberative spaces diminish discursive distances compared with when such spaces enhance discursive distances. The empirical findings in the previous section revealed that this is true because spaces that granted people more time to reflect on what others were saying and feel sufficiently comfortable with others to bring in their personal experiences tended to display a smaller discursive distance between participants. Likewise, other spaces with fewer institutional norms (e.g. the public place), which promote a certain way of thinking, tended to diminish the discursive distance; thus, people were more accommodating of the ‘otherness’ of others. Concerning the latter on the effect of institutions on opinion change, some related studies have provided an opposing view on the effect of institutional norms in shaping opinions.

Piekut and Valentine (2017) as well as Awuh and Spijkers (2020) have combined empirical material and existing literature to distinguish different places based on their role in the relationship between contact and attitude change. They have argued that contact opportunities are excellent in public places but provide little opportunity to change attitudes due to the fleeting nature of interactions. Therefore, these authors have observed more potential in the other types of places in which the regulation of interactions is institutionally sanctioned (as in an obligation to attend a function in the case of institutional places) for nurturing personal interactions and challenging attitudes. They have argued that in semipublic spaces, interactions tend to be between people with close ties (e.g. students and teachers at a school). Thus, in such spaces, there is a higher potential for attitudes to change (Piekut & Valentine, 2017; Awuh & Spijkers, 2020).

Whilst this study agrees that institutions could enhance participation in a deliberation exercise by making it compulsory or obligatory, people often do not have the freedom to fully express how they think or feel because of certain expectations of them. In this study, biology and nutrition students—who constituted the bulk of the sample—possibly could not freely endorse (even if deep down they wanted to) drinking beer and eating deep-fried snacks as healthy when consumed together with others. Therefore, whilst institutional norms might have the potential to enhance attitude change, as Piekut and Valentine (2017) and Awuh and Spijkers (2020) have argued, in the case of public deliberation, it is often not so straightforward because institutional expectations could stifle freedom of expression. In a typical case of reinventing distancing, institutional norms could make it more difficult for people to express certain ideas and perspectives or to accommodate certain views and perspectives. This is because failure to sufficiently distance oneself from the other side and their point of view is disapproved of. This explains why institutional spaces such as schools create more discursive distancing between participants than public spaces where institutional norms are non-existent, as illustrated in the inverted pyramid in Fig. 4.

Another observation is that, as a result of varying degrees of discursive distance, different heterotopias produced different change outcomes. Revisiting the framework presented earlier in this paper, there are several possible outcomes of a deliberation process. These include the following: compromise, awareness, a shift in opinion, respect and the confirmation/reaffirmation of pre-existing opinions. In almost every deliberation process, there is a degree of awareness. This awareness is the gateway to the deliberation process because it lays the framework for the other outcomes. In raising awareness, people get to know about the nature of the issue at hand, not necessarily the actual outcome (Niemeyer & Dryzek, 2007). Here, participants set aside their private interests and engage with alternative views, beliefs and values. In the empirical cases of the face-to-face school heterotopia, the outcome was largely one of compromise. In this case, although opinions did not shift because participants still disproved of eating nutritionally unhealthy food in the practice of eating together, they did put some thought into it by first acknowledging the healthy argument behind the practice of eating together. Therefore, their opinions concerning what constitutes a healthy food practice did not seem to change, as they prioritised nutrition over pleasure in definitions of ‘healthy’. However, some thought was given to the poster, and in that process of thinking, they acknowledged what was good or bad about what they saw on the poster. This is change as an outcome of the deliberation process—deliberation within—despite them not shifting their opinions on their priorities concerning a healthy food practice. Deliberation within means taking in and considering multiple viewpoints, arguments and counter-arguments, but not necessarily voicing them or using them to make a shift in opinion (Goodin, 2000). In the online school and public heterotopias, although the outcome was the confirmation/reaffirmation of pre-existing opinions in both cases, this took different shapes in the two cases. In the online space, following awareness, people did not demonstrate any interest in accommodating or endorsing alternative views. By contrast, in the public space, following awareness, people developed parallel views that demonstrated no significant deviations from the opinions expressed by others on the posters.

The major limitation of this research is that the data collected and presented were only based on reflection-in-action (i.e. how people feel or what they think about a subject on the spot). The problem with this is that some participants might have needed time to go home and reflect on the things they heard at the deliberation event (i.e. reflection-after-action) before deciding whether to shift their opinion. Therefore, it is possible that reflection after the deliberative event, which was not considered in this research, could have increased the number of responses from people who had a shift of opinion as a result of their deliberation. Future research on the outcomes of deliberation should include such a perspective and investigate whether institutional norms and time could still play roles in shaping reflection-after-action outcomes.

In conclusion, a successful public deliberation process must satisfy the following conditions: (1) It must be institutionally sanctioned or set up in a space governed by an institution; and (2) participants in the deliberation process must be given more time to make their arguments and reconsider them in light of what others have to say. These critical methodological limits or preconditions should be acknowledged by those who design, implement and use public engagement methods to inform societal change. They highlight caveats that scholars and practitioners should seek to avoid when using deliberation to influence public opinion. If these conditions are met, the results of an effective deliberation process will be worth the time, cost and effort.

Data availability

The datasets obtained and/or analysed during the current study are available from the author on reasonable request.

Notes

Between radical democratic aspirations of the pre-independence stage and post-independence pluralism.

These are spaces within which a diverse body of citizens who would not otherwise interact is selected randomly to reason together about an issue of public concern.

Dutch word which loosely translates into cosy, enjoyable or pleasant.

References

Abdullah, C., Karpowitz, C. F., & Raphael, C. 2020. Equality and equity in deliberation: Introduction to the special issue. Journal of Deliberative Democracy, 12(2), 1–9.

Agnew, J. A., & Livingstone, D. N. 2011. The Sage handbook of geographical knowledge. Sage Publications.

Awuh, H. E., & Spijkers, F. 2020. ‘We Are Not As Bad as you Think we Are’: Dealing with Diversity and Self-Exclusion in a Youth Football Club. International Journal of the Sociology of Leisure, 3(2), 97–114.

Bächtiger, A., Dryzek, J. S., Mansbridge, J., & Warren, M. E. (Eds.). 2018. The Oxford handbook of deliberative democracy. Oxford University Press.

Baiocchi, G., & Ganuza, E. 2017. Popular Democracy: The Paradox of Participation, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Barrett, G., Wyman, M., & Schattan, P. C. V. 2012. Assessing the policy impacts of deliberative civic engagement. Democracy in motion: Evaluating the practice and impact of deliberative civic engagement, 181–204.

Benhabib, S. 1992. Situating the self: Gender, community, and postmodernism in contemporary ethics. New York: Routledge.

Bessette, J. M. 1994. The mild voice of reason: Deliberative democracy and American national government. University of Chicago press.

Blacksher, E., Hiratsuka, V. Y., Blanchard, J. W., Lund, J. R., Reedy, J., Beans, J. A., ... & Spicer, P. G. 2021. Deliberations with American Indian and Alaska Native People about the Ethics of Genomics: An Adapted Model of Deliberation Used with Three Tribal Communities in the United States. AJOB Empirical Bioethics, 12(3), 164–178.

Blue, G., & Dale, J. 2020. Framing and power in public deliberation with climate change: Critical reflections on the role of deliberative practitioners. Journal of Deliberative Democracy, 12(1), 1–22.

Boréus, K. 2006. Discursive Discrimination: A Typology. European Journal of Social Theory, 9(3), 405–424.

Bourgeois, R., Penunia, E., Bisht, S., & Boruk, D. 2017. Foresight for all: Co-elaborative scenario building and empowerment. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 124, 178–188.

Calhoun, C. 1992. Introduction: Habermas and the public sphere. Boston, Massachusetts: MIT press.

Coelho, V. S. R. P., & Waisbich, L. 2020. Participatory mechanisms and inequality reduction: searching for plausible relations. Journal of Deliberative Democracy, 12(2), 1–16.

Cohen, J. 2009. Reflections on deliberative democracy. Contemporary debates in political philosophy, 17, 247

Constandse, A. K. 1989. Almere: A new town in development: problems and perspectives. The Netherlands journal of housing and environmental research, 4(3), 235–255.

Dean, J, 2015. Technology. The Promises of Communicative Capitalism. In: Azmanova, Albena and Mihaela Mihai (eds.) Reclaiming Democracy. Judgment, Responsibility, and the Right to Politics, New York: Routledge, pp. 50–76.

Degeling, C., Rychetnik, L., Street, J., Thomas, R., & Carter, S. M. 2017. Influencing health policy through public deliberation: lessons learned from two decades of Citizens’/community juries. Social Science & Medicine, 179, 166–171.

Dekking, A., Jansma, J.E., & Visser, A.J. 2007. Urban Agriculture Guide; Urban agriculture in the Netherlands under the magnifying glass. Wageningen University, Applied Plant Research, Lelystad, the Netherlands.

Díaz-Méndez, C., & Gómez-Benito, C. 2010. Nutrition and the Mediterranean diet. A historical and sociological analysis of the concept of a “healthy diet” in Spanish society. Food Policy, 35(5), 437–447.

Dormans, S. E. M. 2008. Narrating the city. Urban tales from Tilburg and Almere (Doctoral dissertation, Nijmegen: RU Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen).

Dryzek, J. S., & Lo, A. Y. 2015. Reason and Rhetoric in Climate Communication. Environmental Politics, 24(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2014.961273.

Elstub, S., Ercan, S., & Mendonça, R. F. 2016. Editorial introduction: The fourth generation of deliberative democracy. Critical Policy Studies, 10(2), 139–151.

Ercan, S. A., Hendriks, C. M., & Dryzek, J. S. 2019. Public deliberation in an era of communicative plenty. Policy & Politics, 47(1), 19–36.

Feddes, F. 2008. The Almere principles; for an ecologically, socially and economically sustainable future of Almere 2030. Bussum, Netherlands: Thoth Publishers.

Feskens, E. 2016. Schijf van vijf 2016; een reactie van de wetenschap. Tijdschrift voor gezondheidswetenschappen, 94(5), 166–166. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s12508-016-0063-9.

Filatova, O., Kabanov, Y., & Misnikov, Y. 2019. Public deliberation in Russia: Deliberative quality, rationality and interactivity of the online media discussions. Media and Communication, 7(3), 133–144.

Fishkin, J. S. 2009. When the People Speak: Deliberative Democracy and Public Consultation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fishkin, J. 2018. Democracy When the People Are Thinking: Revitalizing Our Politics Through Public Deliberation, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Foucault, M. 1966. Les mots et les choses: Une archéologie des sciences humaines. Paris: Gallimard.

Foucault, M. 1967. “Of other spaces,” Diacritics, volume 16, 22–27.

Foucault, M., & Miskowiec, J. 1986. Of other spaces. Diacritics, 16(1), 22–27.

Foucault, M. 2006. Of Other Spaces Utopias and Heterotopias’ and ‘Panopticum’’. Rethinking Architecture A Reader in Cultural Theory, London: Routledge, 350–367.

Gaspar, M. C. D. M. P., Garcia, A. M., & Larrea-Killinger, C. 2020. How would you define healthy food? Social representations of Brazilian, French and Spanish dietitians and young laywomen. Appetite, 153, 104728.

Ghimire, R., Anbar, N., & Chhetri, N. B. 2021. The impact of public deliberation on climate change opinions among US citizens. Frontiers in Political Science, 13.

Goodin, R. E. 2000. Democratic deliberation within. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 29, 81–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1088-4963.2000.00081.x.

Goold, S. D., Neblo, M. A., Kim, S. Y., Vries, R. D., Rowe, G., & Muhlberger, P. 2012. What is good public deliberation? Hastings Center Report, 42(2), 24–26.

Gordon, E., & Baldwin-Philippi, J. 2014. Playful civic learning: Enabling reflection and lateral trust in game-based public participation. International Journal of Communication, 8, 759–786.

Hart, N., & Crawford-Wright, A. 1999. Research as therapy, therapy as research: Ethical dilemmas in new-paradigm research. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 27(2), 205–214.

He, B., & Warren, M. E. 2011. Authoritarian deliberation: The deliberative turn in Chinese political development. Perspectives on Politics, 9(2), 269–289.

Himmelroos, S., & Christensen, H. S. 2014. Deliberation and Opinion Change: Evidence from a Deliberative Mini‐public in F inland. Scandinavian Political Studies, 37(1), 41–60.

Holdo, M., & Öhrn Sagrelius, L. 2020. Why inequalities persist in public deliberation: Five mechanisms of marginalization. Political Studies, 68(3), 634–652.

Irvine, A. 2011. Duration, dominance and depth in telephone and face-to-face interviews: A comparative exploration. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 10(3), 202-220.

Jansma, J. E., & Visser, A. J. 2011. Agromere: Integrating urban agriculture in the development of the city of Almere. Urban Agriculture Magazine, 25(2011), 28–31.

Jansma, J. E., & Wertheim-Heck, S. C. 2021. Thoughts for urban food: A social practice perspective on urban planning for agriculture in Almere, the Netherlands. Landscape and Urban Planning, 206, 103976.

Jennstål, J., & Niemeyer, S. 2014 The Deliberative Citizen: Exploring Who is Willing To Deliberate, When and How Through the Lens of Personality. Working Paper, Centre for Deliberative Democracy and Global Governance, Canberra: University of Canberra, Available from: http://igpa.edu.au/deldem/papers. Accessed Nov 2021.

Karpowitz, C. F., & Raphael, C. 2020. Ideals of inclusion in deliberation. Journal of Deliberative Democracy, 12(2), 3.

Kraeger, P., & Schecter, D. 2020. Mini-public deliberation in philanthropy: A new way to engage with the public. In Kraeger, P. and Schecter, D. (2020) Mini-public deliberation in philanthropy: A new way to engage with the public new Democracy Foundation, 1–8. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=3593158. Accessed Nov 2021.

Kvarnstrom, E. 2015. The Importance of Face-to-Face Contact in Depression Treatment and Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.bridgestorecovery.com/blog/the-importance-of-face-to-face-contact-in-depression-treatment-and-prevention/#:~:text=Face-to-face%20interaction%20may%20also%20encourage%20important%20neurochemical%20changes,pressure%2C%20and%20increased%20willingness%20to%20share%20difficult%20emotions. Accessed Nov 2021.

Lefebvre and Nicholson-Smith, 1991Lefebvre, H., & Nicholson-Smith, D. 1991. The production of space (Vol. 142). Blackwell: Oxford

Lehoux, P., Miller, F. A., & Williams-Jones, B. 2020. Anticipatory governance and moral imagination: Methodological insights from a scenario-based public deliberation study. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 151, 119800.

Levitas, R. 2013. Utopia as method: The imaginary reconstitution of society. Dordrecht: Springer.

Loopmans, M. 2002. From hero to zero. Armen en stedelijk beleid in Vlaanderen. Ruimte en Planning, 22(1), 39–49.

Manin, B. 1987. On legitimacy and political deliberation. Political Theory, 15(3), 338–368.

Marin, I. 2006. Collective decision making around the world: Essays on historical deliberative practices, Dayton, OH: Kettering Foundation.

Medaglia, R., & Zhu, D. 2017. Public deliberation on government-managed social media: A study on Weibo users in China. Government Information Quarterly, 34(3), 533–544.

Mendini, M., Pizzetti, M., & Peter, P. C. 2019. Social food pleasure: When sharing offline, online and for society promotes pleasurable and healthy food experiences and well-being. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 22(4), 544-556.

Min, S. J. 2014. On the Westerness of deliberation research. Journal of Deliberative Democracy, 10(2), 5.

Morozov, E. 2011. The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom/ How Not to Liberate the World, London: Penguin Books.

Munno, G., & Nabatchi, T. 2020. Public deliberation and co-production in the political and electoral arena: a citizens’ Jury Approach. Journal of Deliberative Democracy, 10(2), 1–31.

Niemeyer, S., & Dryzek, J. S. 2007. The Ends of Deliberation: Metaconsensus and Intersubjective Rationality as Deliberative Ideals. Swiss Political Science Review, 13(4), 497–526.

Nisbett, R. E., & Ross, L. 1980. Human inference: Strategies and shortcomings of social judgment. Englewood Cllffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

O’Malley, E., Farrell, D. M., & Suiter, J. 2020. Does talking matter? A quasi-experiment assessing the impact of deliberation and information on opinion change. International Political Science Review, 41(3), 321–334.

Owen, D., & Smith, G. 2015. Survey article: Deliberation, democracy, and the systemic turn. Journal of Political Philosophy, 23(2), 213–234.

Piekut, A., & Valentine, G. 2017. Spaces of encounter and attitudes towards difference: A comparative study of two European cities. Social Science Research, 62, 175-188.

Pitts, M. J., Kenski, K., Smith, S. A., & Pavlich, C. A. 2020. Focus group discussions as sites for public deliberation and sensemaking following shared political documentary viewing. Journal of Deliberative Democracy, 13(2), 1–27.

Polletta, F. 2020. Just talk: Public deliberation after 9/11. Journal of Deliberative Democracy, 4(1), 1–22.

Sen, A. 2003. Democracy and its global roots. New Republic, 229(14), 28–35.

Setälä, M. 2014. Deliberative mini-publics: Involving citizens in the democratic process. Ecpr Press.

Shane, D. G. 2005. Recombinant Urbanism: Conceptual Modeling in Architecture, Urban Design, and City Theory. London: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Sherman, D. K., & Cohen, G. L. 2006. The psychology of self‐defense: Self‐affirmation theory. Advances in experimental social psychology, 38, 183–242.

Stark, A., Thomson, N. K., & Marston, G. 2021. Public deliberation and policy design. Policy Design and Practice, 1–13.

Soja, E. W. 2013. Seeking spatial justice (Vol. 16). University of Minnesota Press.

Stilgoe, J., Watson, M., & Kuo, K. 2013. Public engagement with biotechnologies offers lessons for the governance of geoengineering research and beyond. PLoS Biology, 11(11), e1001707.

Stirling, A. 2008. “Opening up” and “closing down” power, participation, and pluralism in the social appraisal of technology. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 33(2), 262–294.

Viana, M. R., Neves, A. S., Camargo Junior, K. R., Prado, S. D., & Mendonça, A. L. O. 2017. A racionalidade nutricional e sua influência na medicalização da comida no Brasil. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 22, 447–456.

Voedingscentrum. 2022. Homepage. Retrieved from https://www.voedingscentrum.nl/nl.aspx. Accessed Nov 2021.

Funding

This research is part of the Almere Kennisstad (growing green cities) project funded by Flevo Campus (Almere, The Netherlands).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in this study. The participants were informed about the purpose of the research and what the data will be used for. Participation was voluntary and participants could withdraw their consent and discontinue participation at any time without prejudice.

Conflict of interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Awuh, H.E. Geographies of Public Deliberation: A Closer Look at the Ingredient of Space. Soc 60, 893–906 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-023-00907-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-023-00907-z