Abstract

Education level—often referred to as the “diploma divide”—has been implicated as one of the key cleavages in the 2016 presidential election. This piece explores this division over time, along with the most common explanations of the education cleavage in 2016, class and racial resentment. Voters’ views on the value of expertise are added as a possible explanation of the 2016 electoral divide by education level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Donald Trump’s victory in the 2016 presidential election was a development that very few experts—among both academics and the punditocracy—saw coming. Indeed, according to many accounts Trump’s own campaign did not think he would win, up to and including Election Day (Schreckinger 2017; Wolff 2018). Trump himself acknowledged that he believed he was going to lose in a speech in Wisconsin in December 2016, recalling to supporters how he went to his wife Melania on Election Day and said: “Baby, I’ll tell you what, we’re not going to win tonight…” (McCaskill 2016). Trump’s 2016 win is one of the most shocking American presidential election outcomes of all time, surpassed perhaps only by Harry Truman’s victory over Thomas Dewey in 1948.

Almost immediately analysts of all stripes—journalists, political operatives, elections scholars—began the process of attempting to understand and explain Trump’s victory. Why and how did he win? A quick glance at the exit poll results showed substantial differences in vote choice on the basis of race (Trump won among whites 57% to 37%, while Hillary Clinton led among non-whites 74% to 21%) and education level (Trump led among non-college graduates 51% to 44%, while Clinton won college graduates 52% to 42%).Footnote 1 Very quickly the claim that working-class whites were the key to Trump’s win became the predominant frame in understanding the results. On the day after the election, both the New York Times and the Washington Post—arguably the two most important daily newspapers in the United States—ran stories featuring this explanation. The Times piece, written by Nate Cohn, had a headline of “Why Trump Won: Working Class Whites,” and opened with this sentence: “Donald J. Trump won the presidency by riding an enormous wave of support among white working-class voters” (Cohn 2016). The Post article, written by Jim Tankersley, was titled “How Trump Won: The Revenge of Working Class Whites,” and presented its pointed explanatory statement over the first three, short paragraphs:

For the past 40 years, America's economy has raked blue-collar white men over the coals…On Tuesday, their frustrations helped elect Donald Trump, the first major-party nominee of the modern era to speak directly and relentlessly to their economic and cultural fears. It was a ‘Brexit’ moment in America, a revolt of working class whites who felt stung by globalization and uneasy in a diversifying country where their political power had seemed to be diminishing (Tankersley 2016).

Both pieces agreed that white voters without a college degree were primarily responsible for the fact that Donald Trump would be sworn in as the forty-fifth President of the United States. But pointing the finger at the white working class also raised the question of which element was more important—race or class? Tankersley’s piece added another intriguing element by specifically singling out men among the disgruntled white working class.

This article examines the various explanations that have been offered for the strong support of Trump by non-college educated whites, with an eye toward understanding why these voters were so attracted to Trump in 2016. It is clear that both race and class are critical to making sense of vote choice among this group, as lower levels of education, economic struggle and insecurity, and racial anxiety and resentment are intimately interconnected. This piece adds a new possible explanation for non-college educated whites’ class support of Trump in 2016—Trump’s condemnation and rejection of expertise. The article closes with speculation on how Trump’s disdain for science and rejection of virtually all forms of expert knowledge might play out on Election Day 2020.

Education

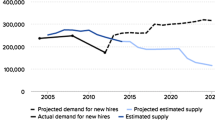

There is little doubt that education level was an important factor in vote choice among whites in 2016. Multiple reports and analysts point to the fact that the so-called “diploma divide” among whites was highly relevant in the 2016 presidential election (Harris 2018, Miller 2018; Pew 2018; Sances 2019). And there is no doubt that Trump benefitted immensely from high levels of support among less educated white voters at the same time he fared poorly among whites with a bachelor’s degree or higher (Cohn 2018; Pew 2018; Sides et al. 2018; Silver 2016). It is also clear that less educated voters were critical in Trump’s success in the primaries that ultimately secured him the Republican nomination (Dyck et al. 2018; McVeigh and Estep 2019). But Republican success among non-college educated whites did not begin with Trump in 2016. As Jones (2019) and Sides et al. (2018) show, the movement of non-college whites toward the GOP and college-educated whites toward the Democratic Party predates Trump’s candidacy. As Table 1 shows, Republicans have had the advantage among non-college educated whites relatively consistently for almost 70 years, save for brief interruptions by Lyndon Johnson in 1964 and Bill Clinton in both 1992 and 1996. It is important to note that Trump’s edge among non-college educated whites was the largest since Ronald Reagan in 1984, but a Republican presidential candidate doing well among non-college whites is not that unusual. Where Trump really stands out is how much better he did among non-college educated whites than among whites with a degree. His 21-point advantage here is the largest in the period covered by the American National Election Studies (ANES). Both results point to Trump’s strong appeal among non-college educated whites, while at the same time indicating that something about Trump troubled at least some college-educated white voters.

Explanations

It is one thing to point out the large education divide among whites in the 2016 presidential election. But by far the more interesting exercise is attempting to explain it. Many of the earliest accounts pointed to class as the primary explanation. As Tankersley (2016) pointed out in his day-after assessment, rural whites working in blue-collar occupations (and therefore unlikely to have a college degree) had been suffering for years in the United States as the fundamental nature of the American economy changed. Their struggles had been exacerbated by both the Great Recession and the ever-increasing pace of globalization. Trump appealed to non-college educated whites on economic grounds early and often throughout the campaign, promising to look out for their interests by ending bad trade deals and bringing manufacturing jobs back to the United States, specifically back to the nation’s rural areas (Michaels 2017; Swanson 2017). And indeed, if one looked at class measures (such as family income) and economic anxiety concerns (such as worries about finances, job insecurity, and inability to pay one’s bills) on their own, it did appear that non-college educated whites supported Trump at least partially on the basis of class concerns (Abramowitz 2018; Sides et al. 2018). It appeared that Trump’s economic appeals and promises had worked, pushing less educated whites to vote for him in the hope of a brighter economic future for themselves and their families.

Such appearances vanished, however, as soon as scholars started taking a more detailed and nuanced look at the data. Sides et al. (2017) were the first to publish such findings. Using multivariate analysis, Sides and his colleagues demonstrated that levels of white support for Trump were heavily determined by views on race, ethnicity, and immigration. Simply put, the more negative their views on African Americans, others seen as non-white, and immigrants; the more they believed whites were subject to discrimination; and the more central whiteness was to their identity, the more likely whites were to vote for Trump over Clinton (Sides et al. 2017). Sides et al. followed their short 2017 article with a 2018 book that carefully and meticulously laid out the evidence for their argument that attitudes about race and immigration, not economic anxiety or class concerns, were the primary explanation for vote choice among whites in the 2016 presidential election (Sides et al. 2018).

Many similar analyses soon followed. Abramowitz (2018) argued that racial fear and resentment explained whites voting for Trump. Class made little difference after racial concerns were introduced into the analysis. Using different datasets and measuring racial and class concerns in different ways, the number of studies demonstrating that concerns over race, ethnicity, and immigration were the driving force behind white support of Trump grew dramatically throughout 2018 and 2019 (Bunyasi 2019; Green and McElwee 2018; Hooghe and Dassonneville 2018; Margalit 2019; Rowland 2019; Schaffner et al. 2018; Setzler and Yanus 2018). Mutz (2018) added greater depth to these findings by bringing racial and immigration concerns together under the umbrella of “status threat,” arguing that the groups long dominant in American society—predominantly determined by race but also including sex and religion—were becoming increasingly unsettled as the United States became more diverse and its position in the world changed. Higher levels of these concerns pushed whites toward Trump. Racial resentment—measured using the scale from Kinder’s and Sanders’s seminal 1996 work—was critical in understanding how race played into white support for Trump. Those who agreed that blacks should work their way up without favors in the way that other minority groups did and that blacks lagged behind whites economically because they did not work hard enough, and disagreed that the lengthy history of slavery and discrimination made it hard for blacks to succeed and that blacks have gotten less than they deserve, voted heavily for Trump. Various measures of anti-immigrant sentiment worked in the same way. Concerns about losing one’s place of privilege also pushed whites to Trump. These racial, immigration, and status measures maintained their statistical significance in multivariate analyses, while measure of class and economic concern did not. More important for this study, the inclusion of the various racial, immigration, and status variables always reduced education level to statistical non-significance (Abramowitz 2018; Hooghe and Dassonneville 2018; Mutz 2018; Schaffner et al. 2018; Setzler and Yanus 2018; Sides et al. 2018). As we head toward the finish line in the 2020 presidential election, the apparent consensus explanation of Trump’s 2016 success among non-college educated whites is rooted in racial, immigration, and status concerns.

A Possible Addition—The Rejection of Expertise

There is little doubt that racial resentment and anxiety, anti-immigrant sentiment, and concerns over the loss of privileged status were critical to Trump’s victory in 2016. I would argue that there are economic and class elements intertwined in each of these perspectives (McVeigh and Estep 2019), but the explanatory power of these measures on the white vote in 2016 cannot be disputed. I do, however, want to propose a potential addition to this explanation: the rejection of expertise.

As both a candidate and now as president, Trump presents a rejection of expertise and a devaluing of scientific knowledge on an unprecedented scale. No major-party presidential candidate or sitting president—at least in the modern era—has ever attacked and belittled experts and their expertise to the degree that Trump has. Certainly previous presidents of different parties have chosen to surround themselves with different schools of expertise, listening to some experts while ignoring others. But Trump seemingly rejects all expertise, save for his own. This is the man, after all, who after presenting the United States as a nation teetering on the brink of destruction as he accepted the 2016 Republican presidential nomination, declared: “I alone can fix it.” Trump has followed this belief as president. He rejects expertise in the belief that he knows more than the experts, and therefore both he and the nation are better served by his making decisions based on his “gut,” famously telling the Washington Post in 2018: “I have a gut, and my gut tells me more sometimes than anybody else’s brain can ever tell me,” (Rucker et al. 2018). I argue that Trump’s supporters agree, and that their rejection of experts and their expertise is critical in understanding why they support Trump.

The appeal to some voters of Trump’s rejection of expertise is rooted in the appeal of populism to some segments of the American electorate. American populism has always featured a strong strain of anti-elitism and anti-intellectualism (Brewer 2016; Conley 2020; Hofstadter 1962, 1966; Lacatus 2019; Rowland 2019). Trump embraces both of these. Anti-intellectualism leads to opposition to experts and their proposed solutions to the problems of the day (Merkley 2020). As Rowland (2019) puts it, populism “rejects the pretensions of experts.” Here too, Trump fits the bill. In American populism generally, and especially in Trump’s particular populist strain, the elites of American society are morally bankrupt actors who for decades have been using the power of the state to benefit themselves and harm average Americans, destroying the greatness of America as they go. Trump tells his supporters that he will end this practice. His displacement of the elites and assumption of decision and policymaking authority totally to himself will allow Trump to return the United States to a country that benefits average Americans, and “make America great again.” This is what Trump has offered and promised to Americans, and I argue that it is critical in understanding why his supporters, especially whites without a college degree, support him. They too reject elite experts and their expertise, and see Trump as their champion against a cabal of elites who consistently work against their interests and impose harm.

There are far too many examples of Trump rejecting expertise to recount in a piece of this length. Trump has repeatedly rejected views of experts in foreign policy (military and diplomatic), trade, fiscal and monetary policy, intelligence and national security, immigration, and the environment, to name but a few. The list could go on and on. Trump has stripped government of expertise to a degree that has never been seen before (Kalb 2018). In a recent report by the Union of Concerned Scientists, Carter et al. (2020) make the case that the Trump administration’s attacks against science are unprecedented. The evidence they lay out is hard to ignore. Among other things, the report documents that the Trump administration has:

-

“Weakened or disbanded a number of federal advisory committees”

-

Left vacant a “high proportion of scientific leadership appointments”

-

Engaged in significant cuts in scientific funding

-

Empowered political appointees over scientists

-

Forced scientists to stop work or not publicize completed work

-

Deleted valid scientific information for public-facing government websites

-

Censored and retaliated against government scientists for their work

Carter et al.’s report ends with this conclusion:

The Trump Administration's unprecedented attacks on science highlight an urgent need for the next president to restore integrity in science-based decision making. This administration has sidelined scientific guidance from experts inside and outside of agencies, directly censored scientists, suppressed federal scientific reports, and created a chilling environment that has demoralized federal scientists and led to self-censorship of their work (16).

Carter et al.’s comments about scientists and their expertise can easily be extended to experts and their expertise more broadly. I argue that whites (and Americans more broadly) with college degrees react negatively to Trump’s attacks on experts and their knowledge. But non-college whites agree with Trump here, and this agreement is critical for understanding their support. Trump’s “unending recrimination of elites” (Conley 2020) and relentless attacks on the elite political establishmentFootnote 2 appeal to these voters, who see elites as corrupt snobs who look down on and demean them. In the same way he speaks to non-college whites on race, immigration, and status, Trump speaks their language on elites and their expertise. These voters, in turn, reward Trump with their support.

Given all of this, Trump’s rejection of expertise bears watching in the 2020 election. Of course Americans are currently living through what will undoubtedly go down as Trump’s most significant rejection of expertise: his handling of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. According to the New York Times, there have been 192,000 deaths in the United States from COVID-19 as of September 11, 2020. The latest forecast from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington predicts over 410,000 deaths in the United States by the end of 2020 (Achenbach and Wan 2020). How will Americans respond? I strongly suspect that this response will be mediated to some degree by education level. What that degree is remains to be seen.

Notes

All exit poll results as reported by CNN: https://www.cnn.com/election/2016/results/exit-polls

The examples of this are virtually limitless, but for two more prominent examples, one can see Trump’s first inaugural address and his 2020 Republican nomination acceptance speech.

Further Reading

Abramowitz, Alan I. 2018. The Great Alignment. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Achenbach, Joel, and William Wan. 2020. "Experts Warn U.S. Covid-19 Deaths Could More Than Double By Year's End." Washington Post. September 4.

Brewer, Mark D. 2016. "Populism in American Politics." The Forum 14 (3): 249-264.

Bunyasi, Tehama L. 2019. "The Role of Whiteness in the 2016 Presidential Primaries." Perspectives on Politics, 17 : 679-698.

Carter, Jacob, Taryn MacKinney, Genna Reed, and Gretchen Goldman. 2020. "Presidential Recommendations for 2020: A Blueprint for Defending Science and Protecting the Public." Union of Concerned Scientists. January.

Cohn, Nate. 2016. "Why Trump Won: Working-Class Whites." New York Times. November 9.

Cohn, Nate. 2018. Trump Losing College Educated Whites? He Never Won Them in the First Place." New York Times. February 27.

Conley, Richard S. 2020. Donald Trump and American Populism. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press.

Dyck, Joshua J., Shanna Pearson-Merkowitz, and Michael Coates. 2018. "Primary Distrust: Political Distrust for the Insurgent Candidacies of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders in the 2016 Primary." PS, 51 (2): 351-357.

Green, Jon, and Sean McElwee. 2018. "The Differential Effects of Economic Conditions and Racial Attitudes in the Election of Donald Trump." Perspectives on Politics, 17 (2): 359-379.

Harris, Adam. 2018. "America Is Divided By Education." The Atlantic. November 7.

Hofstadter, Richard. 1962. Anti-Intellectualism in American Life. New York: Random House.

Hofstadter, Richard. 1966. The Paranoid Style in American Politics. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Hooghe, Marc, and Ruth Dassonneville. 2018. "Explaining the Trump Vote: The Effect of Racist Resentment and Anti-Immigrant Sentiments." PS, 51 (3): 528-534.

Jones, Jeffrey M. 2019. "Non-College Whites Had Affinity for GOP Before Trump." Gallup. April 12.

Kalb, Marvin. 2018. Enemy of the People. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Kinder, Donald B., and Lynn M. Sanders. 1996. Divided by Color: Racial Politics and Democratic Ideals. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lacatus, Corina. 2019. "Populism and the 2016 American Election: Evidence from Official Press Releases and Twitter." PS, 51 (2): 223-228.

Margalit, Yotam. 2019. "Economic Insecurity and the Causes of Populism, Reconsidered." Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33 (4): 152-170,

McCaskill, Nolan. 2016. "Trump Tells Wisconsin: Victory Was a Surprise." Politico. December 13.

McVeigh, Rory, and Kevin Estep. 2019. The Politics of Losing. New York: Columbia University Press.

Merkley, Eric. 2020. "Anti-Intellectualism, Populism, and Motivated Resistance to Expert Consensus." Public Opinion Quarterly, 84 (1): 24-48.

Michaels, Allison. 2017. "Will Trump Bring Back American Manufacturing Jobs?" Washington Post. July 21.

Miller, Patrick R. 2018. "The 2016 Southern Electorate: Demographics, Issues, and Candidate Perceptions." In The Future Ain't What It Used To Be. Edited by Branwell Dubose Kapeluck and Scott E. Buchanan. Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Press, pp. 3-21.

Mutz, Diana. 2018. "Status Threat, Not Economic Hardship, Explains the 2016 Presidential Vote." PNAS, 115 (19): E4330-E4339.

Pew Research Center. 2018. "For Most Trump Voters, 'Very Warm' Feelings for Him Endured." Washington, DC. August 9.

Rowland, Robert C. 2019. "The Populist and Nationalist Roots of Trump's Rhetoric." Rhetoric and Public Affairs, 22 (3): 343-388.

Rucker, Philip, Josh Dawsey, and Damian Paletta. 2018. "Trump Slams Fed Chair, Questions Climate Change, and Threatens to Cancel Putin in Wide-Ranging Interview With the Post." Washington Post. November 27.

Sances, Michael W. 2019. "How Unusual Was 2016? Flipping Counties, Flipping Voters, and the Education-Party Correlation Since 1952." Perspectives on Politics, 17 (3): 666-678.

Schaffner, Brian F., Matthew MacWilliams, and Tatishe Nteta. 2018. "Understanding White Polarization in the 2016 Vote for President: The Sobering Role of Racism and Sexism." Political Science Quarterly, 133 (1): 9-

Schreckinger, Ben. 2017. "Inside Donald Trump's Election Night War Room." GQ. November 7.

Setzler, Mark, and Alixandra B. Yanus. 2018. "Why Did Women Vote for Donald Trump." PS, 51 (3): 523-527.

Sides, John, Michael Tesler, and Lynn Vavreck. 2017. "The 2016 U.S. Election: How Trump Lost and Won." Journal of Democracy, 28 (2): 34-44.

Sides, John, Michael Tesler, and Lynn Vavreck. 2018. Identity Crisis. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Silver, Nate. 2016. "Education, Not Income, Predicted Who Would Vote For Trump." fivethirtyeight. November 22.

Swanson, Ana. 2017. "Trump Promised to Make Trade Fair Again. Is He Succeeding?" Washington Post. July 5.

Tankersley, Jim. 2016. "How Trump Won: The Revenge of Working Class Whites." November 9.

Wolff, Michael. 2018. Fire and Fury: Inside the Trump White House. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brewer, M.D. Trump Knows Best: Donald Trump’s Rejection of Expertise and the 2020 Presidential Election. Soc 57, 657–661 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-020-00544-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-020-00544-w