Abstract

Even though political science is one of the most extensive research fields within the social sciences, there is little scholarly knowledge about its publishing trends and the internationalization of the discipline. This paper analyzes international publishing by taking a close look at publishers, Scopus-indexed journals, articles, and author collaboration networks. The results show that the number of political science journals almost tripled between 2000 and 2022. Our descriptive analysis also reveals that only a few Western commercial international publishers, and Taylor & Francis in particular, dominate the publication of political science journals, and Western authors account for the majority of both academic papers and citations. Additionally, our research explores that the most prolific country in terms of publication within political science is still the United States, but the BRICS countries, especially India, Russia, and China, have achieved remarkable growth in their publication outputs. Finally, our network analysis suggests that the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia occupy central positions in international collaborations among political scientists, but Asian, Eastern European and Latin-American regional networks have been developing in the last decade.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Publishing research papers in prestigious academic journals and the internationalization of science are intertwined. Although internationalization in publishing is an essential step toward academic knowledge transfer beyond institutions and states, the distribution of the most productive countries is heavily skewed in favor of the United States and the United Kingdom [1]. Considering the “publishing industry,” many researchers agree that academic journals primarily disseminate scholarly knowledge via research papers in contemporary science [1,2,3]. Most published studies are written by two or more authors [4], proving that scientific collaboration within and beyond institutions and states is inevitable. Since scientific databases such as Scopus collect extensive data on bibliometrics, researchers have an opportunity to understand publication patterns and the internationalization of various research fields. Researchers have taken advantage of bibliometrics and started to analyze the network structures, publication patterns, and the growth of scholarly knowledge in various fields, including the social sciences [1, 4,5,6,7]. Bibliometric analysis of the different research fields is useful because it helps to evaluate researcher performance, contributes to learning which institutions and authors are prominent in specific research fields, supports understanding the past and current state of science, and can predict future knowledge production trends [8,9,10]. This paper also relies on bibliometrics and focuses on publication trends within political science.

Political science is particularly interesting because the experts in this field consciously review the developments and the state of their discipline [11]. Additionally, political science is an exciting field because editors’ decisions in accepting or rejecting manuscripts can outline those political issues that are “worth” scholarly attention. Since political science consists of many research topics, for example: international relations, public opinion, comparative political science, political sociology, political economy, the oppression of human rights, public choice, public policy, public administration, and political communication [12,13,14,15], it has an important, if not central, position among the social sciences. Finally, a small but growing number of articles deal with bibliometrics in political science, showing that the importance of analyzing international publication trends in political science can contribute to our understanding of global political debates [16].

This paper aims to advance bibliometrics and analyze all the published papers in political science in every Scopus-indexed journal since 2013 to depict this field’s publication patterns. Moreover, we also analyze every Scopus-indexed journal’s affiliation and publisher in political science from 2000 onwards to give a more informative picture of publishing in this research field. We chose Scopus to collect the relevant data because it is “the largest database of abstracts and citations of peer-reviewed literature containing active coverage of nearly 25,000 journals published by more than 5000 international publishers and covering periods” [1]. This paper is an exploratory one that utilizes quantitative, descriptive, and network analyses to reveal publishing trends and collaborations in political science between states [16]. Our results suggest that the hegemony of the US and UK institutions is unquestionable in terms of publication output, citations, and H-indices. Furthermore, our outcomes demonstrate that the US and UK’s central positions are spectacular in the publication network of the most prolific political scientists. However, there is a clear and very important trend that shows some decline regarding the publication productivity of the United States, together with a stronger position for Western Europe and Asia. Even more importantly, our analysis shows that Russia was able to significantly raise the number of its internationally published papers in political science, and it has a significant position in the international collaboration network of political science scholars today.

Literature Review

As stated above, a few valuable studies have analyzed bibliometric data in political science so far [13, 16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. We summarize the most important and relevant findings in this subchapter. Prominent researchers have outlined a clear message regarding publication trends in political science: “Publications in most academic journals in political science are stones that fall into the pool of disciplinary discourse without causing a ripple” [18]. In other words, if researchers aim to gain considerable impact in political science, they should not struggle to publish several papers in lower-ranking journals but to publish a single piece of research in one of the top ten periodicals [18]. The above political science journals were research ranked by considering their impact: seven of the top ten journals are affiliated with the United Kingdom, while the rest are embedded in the United States [18].Footnote 1

Wæver [2] analyzed the distribution of authors by their locations in prestigious European and American international relations journals. His findings clearly show the distribution of authors between 1970 and 1995: American authors’ shares from publications are between 66 and 100% in North American journals. The aforementioned results indicate that “American [international relations] journals are not becoming more ‘global’” [2] in the long run. Even though the distribution of authors in the sense of publication was more balanced in European journals, authors beyond North America and Europe published in those journals at a maximum of 14.3% of the time [2].

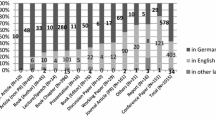

Chi [19] analyzed the bibliometrics of two top-ranking political scientific departments in Germany. The analysis was conducted on a database consisting of bibliometrics between 2003 and 2007. Unsurprisingly, Chi [19] found that publications written in English receive more citations than works written in German. Leifeld et al. [23] also focused on German political scientists: they analyzed the entire co-author network (1339 researchers) of German political science. The outcomes revealed that the following few well-connected institutions in Berlin host the most influential and central political scientists: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung, the German Institute for International and Security Affairs, and Freie Universität Berlin [23].

Kristensen [20] analyzed the bibliographic coupling of references in more than 20,000 articles in international relations between 2005 and 2009 and found that the network of international relations journals is dominated by American periodicals. Furthermore, the aforementioned study also revealed that authors located in the United States tend to publish more in American journals, while scholars affiliated to Europe are willing to publish their works in European journals, which makes the discipline divided [20]. In his conclusion, Kristensen [20] states that “non-Western journals are conspicuously absent” [20].

Jensen and Kristensen [24] analyzed the citation structures of four EU studies journals between 2003 and 2010 by scrutinizing 2561 documents because “citation network constitutes a latent structure of communication, a specific citation practice that EU scholars acknowledge is there but nevertheless tend to leave unaddressed” [24]. Their goal was to reveal the network characteristics of the most important sources dealing with EU studies. The results indicate the dominance of the Anglophone sources, but there is a divide between these sources (including journals). Specifically, sources from the United States tend to cite US-affiliated papers, while European sources mostly cite the works of European-affiliated scholars. The outcomes imply solid evidence on geographical clustering between European and US journals: the former refers to mostly pluralist and non-positivist sources, while the latter cites positivist sources [24].

Metz and Jäckle [25] analyzed the number of co-authors political scientists had between 1990 and 2013. Their analysis showed that the co-author numbers of the most-connected researchers range from 41 to 86. Their findings show that nglophone authors dominate, and were the most central political scientists (e.g., closeness and betweenness centrality in the network). The above study revealed that the more co-authors a researcher has, the more connected they become in the political science network. Moreover, well-connected political scientists cooperate with each other strongly, and there is a similar trend among the most prolific researchers in the field [25].

Researchers analyzed the bibliometrics of an important journal in the field, namely European Political Science (EPS) [13]. The most productive and influential authors at EPS had affiliations at Western institutions; six British, one Irish, Canadian, Portuguese, and German universities provided the most prolific political scientists. The research went further and also explored the most productive and influential institutions at EPS. The results show that British, Italian, Portuguese, Canadian, Dutch, and German universities dominate this prestigious journal [13].

One of the most extensive analyses on political science bibliometrics was conducted by Carammia [16], who studied 67,000 articles in 100 high-impact journals between 2000 and 2019. According to Carammia [16], scholars hosted in the United States contributed the most to knowledge production between 2010 and 2019. In terms of production, the United States is top, followed by the United Kingdom and Germany. Among European political scientists, those from the United Kingdom, Germany, and the Netherlands are involved to the largest extent in international collaboration. Moreover, American (40%) and British (15%) institutions provided more than half of the articles published in top-tier political scientific journals. Considering collaboration networks in co-authorship by country, the United States and the United Kingdom were in central positions between 2000 and 2009 and could stabilize their critical role in the following decade. Carammia [16] also concluded that in Europe, mostly two subgroups exist in political science: “a larger group of scholars based in seventeen countries; and an even more integrated, highly productive and connected core of scholars based in seven northern European countries” [16].

While there are former studies that focused on publication trends in political science, we have only a limited knowledge of the complex publishing patterns that entail both the ownership of academic publishers in political science, the geographic diversity of political science journals, and the publication trends and collaborative publication networks of political science scholars. In order to provide a complex, systematic, and detailed analysis on the abovementioned features of publishing in the field of political science, we outlined the following research questions:

-

RQ1:

What publication trends characterize the Scopus-indexed journals in political science since 2013?

-

RQ2:

What are the characteristics of internationalization in the Scopus-indexed journals in political science for the past two decades?

Methods and Results

To address our research questions we applied both descriptive statistics (RQ1 and RQ2) and network analysis (RQ2). For the analysis of the publication trends we selected the most related Scimago Journal Rank (SJR) category: political science and international relations. In scrutinizing the participation of different publishing houses from the market of political science journals, we worked with the latest SJR data (2019–2022). Then, as Table 1 shows, we calculated three values for each publishing house: (a) the number of different journal titles they published in the analyzed period; (b) the number of different papers they published in the analyzed period; (c) the impact of the published papers as measured by the number of citations.

The results show that Taylor & Francis owns almost a quarter of the journals, and the ten most productive publishing houses publish more than half of all the journals and almost 60% of the published papers in political science. More importantly, the journals of these publishers provide even more impact than production as the journals of the ten most prolific publishers account for more than 80% of the field’s impact. Accordingly, the influence of the giant publishing houses’ journals on the field of political science is even more than it can be estimated by their production. It means that they do not just publish the most journals but, even more importantly, they publish the most influential journals.

Next, we calculated the share of different countries in political science publishing, with a specific attention to open access publication trends. Moreover, as Table 2 shows, we made the same analysis in the case of the top-ranked political science journals indicated by the Q1 category in Scopus/Scimago.

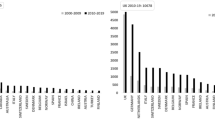

The general publication trend in political science shows a rapid growth with almost three times more journals in 2022 than in 2000, and now the amount of open access journals is 20%. While the same ratio amongst Q1 journals is only 14%, we must emphasize that it was 0% until 2010, so we can see that at least some of the Q1 journals had to consider open access publishing in the last decade. However, as we will show later, Q1 open access publishing has very strong regional differences.

Regarding open access, results show that, similarly to the trends in other disciplines [26] Latin-America has a leading position in open access publishing as the vast majority of their Scopus journals provide open access publication. While the participation of this region in Q1 journals is still very limited (there were only two Q1 journals published in Latin-America in 2022), they retained the open access model even in the case of their leading journals. Eastern Europe is another region where open access publication flourishes with open access journals accounting for 50% of the entire sample, and only one Eastern European Q1 journal follows an open access model, too. Asia is a bit more moderate in terms of open access publishing, but there is clearly a growing tendency towards open access as the amount of open access journals has grown from 10 to 27% between 2000 and 2022. The participation of Africa and the Middle East is marginal in political science publishing, so we cannot estimate clear trends for them.

In the case of Western Europe, we defined two groups: the UK and Western Europe without the UK, and continental Europe. It is an important distinction because the UK publishes many more journals than all the other Western European countries together, so without this distinction the data and would show a bias. Results indicate that political science publishing in Western Europe (without the UK) is skyrocketing as this region has produced the most considerable growth in the last two decades with more than four times as many journals in 2022 than in 2000. The open access ratio is as high as in Asia: in 2022, more than a quarter of all the journals are published through open access and, more importantly, almost half of the Q1 journals are open access journals. With this, while Latin-America is the front-runner in open access publishing, Western Europe is the front-runner in Q1 open access publishing. The United States still has a considerable number of journals, but by 2022 it was lagging behind both the UK and Western Europe with a relatively limited amount of open access journals (10%). Still, the most modest country in terms of open access is the UK, which has almost half of all the journals and two thirds of the Q1 journals. Here open access journals still amount to under 5% which leaves the vast majority of UK journals, and correspondingly the vast majority of Q1 journals, as subscription-based outlets.

Thus far we have analyzed the regional distribution of the publishers: now we turn to the analysis of the national distribution of the journal authors. As the next step, we collected longitudinal data on the publication output of different countries over the last two decades, more precisely, from 2000 to the latest available data (2022). For data collection we used the Scimago Journal country rankings database that shows the country of affiliation of the authors. Table 3 shows the ranking of the top 10 most productive countries in 5-year periods. The results show that the US and the UK remain the leading countries in publishing over the last two decades, India also has a stable position, but there are interesting regional changes in the sample. For instance, China, which had previously focused more on natural sciences and engineering, appeared amongst the most productive countries in political science in 2022. Even more striking is the publication record of Russia that only appeared amongst the top publishers in 2015 and now stands in third place following the US and the UK.

Considering all the countries that published in political science, we calculated the regional contribution of different world regions as well (Table 4). Results show a clear decline in the hegemony of North America as the amount of papers from there decreased significantly, from 38% in 2000 to 18% in 2022. The most significant development can be seen in Western Europe with even more growth in citations than in production in 2022, accounting for almost the half of all citations. Another trend is the development of Eastern European publication, which rose from 2 to 12% in 2022, mostly as a consequence of the skyrocketing number of published papers from Russian authors. Finally, Asia and the BRICS countries show steady, systematic growth, but unlike Eastern Europe they have shown a significant increase in the number of citations as well.

To address our second research question, we analyzed the international collaboration patterns of the ten most productive countries in political science. Table 5 shows that there is steady growth in international cooperation in all the analyzed countries, except Russia, and we can also see that the most significant development took place in those countries in the Western world that had a low level of international collaboration 10 years ago. So, for example, international collaboration almost doubled in the US and the UK where the level of internationalization was relatively low in 2013, while there is only a moderate growth in Germany and the Netherlands where internationalization was already high in 2013. In sum, international papers account for more than 25% of the total in each Western country while it is still relatively low (around 10%) in Russia and India.

Taking the most productive countries as reference points, we downloaded their internationally coauthored papers for the last 10 years (2013–2022) from Scopus. Based on this data, we developed a cooperation network where nodes represent the countries of the internationally coauthored papers the edges of which represent the cooperation between different countries. Edge weights represent the frequency of the international cooperation between the corresponding countries (Fig. 1).

As can be seen in Fig. 1, the most international countries in political science publishing are the four English speaking countries (the UK, the US, Canada, and Australia) together with Germany. These countries do not only collaborate a lot with other countries, but the majority of their collaborations are with each other, thus, for example, US-UK cooperation is extremely frequent. Scandinavian countries are very international and collaborate a lot with other Western European countries and with US authors as well, but they still form a Scandinavian—North European sub hub with Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland.

China has an important publication tie to the US and, in a more moderate way, to other important Western countries. Together with its Western relations, China is an important intermediate point between the Western world and other Asian countries such as Pakistan, Hong Kong or Taiwan that have many collaborative papers with Chinese authors but only moderate connection with Western peers. Japan is another intermediate point in Asia as it connects some economically developed Asian countries such as South Korea, and some economically developing countries such as Thailand or Indonesia, to the international publication network in political science. In sum, while Asian countries tend to be very international and, especially through China, they have significant Western collaborations, they still have an Asian hub so the collaboration between different Asian authors—especially in the case of less cooperative Asian countries—are still very typical.

Another hub is formed by the Eastern European countries with Russia in a central position. Russia is less international than China, but still has significant ties to some Western European countries and the US, and it is an important intermediate point between underrepresented Eastern European countries and the central Western hub.

As Fig. 1 shows, there is a linguistically and culturally distinguished subgraph formed by the most productive Iberoamerican countries: Spain and Brazil. Many Latin-American authors collaborate with these countries, while Spain and Brazil themselves tend to publish authors beyond Iberoamerica with a specific focus on Western European countries.

Finally, South Africa is also in an important position, most likely because of its colonial ties to the Western world. Similarly to China’s position in the Asian hub, South Africa, beyond its strong Western collaboration, connects other African countries to the international network.

Discussion and Conclusions

The academic publishing industry is held to be both diverse (as indicated by the large number of publishing houses and university publishers) and centralized, as the majority of well-known international academic journals is in the hands of huge, established, and profit-oriented publishers [26]. It terms of ownership, it can lead to the hegemonic position of giant publishers, typically located in the US and the UK, as they publish the most important, most popular and most prestigious journals [27]. Former studies have found that, in terms of authorship in political science, the leading position of the US and the UK is unquestionable [13, 16] and our current analysis found that the same holds true for journal publishers as well. The leading position of Taylor and Francis is evident as it publishes almost one quarter of the indexed political science journals. While, according to former studies, the primacy of Taylor and Francis holds for other disciplines such as law and legislation, researchers found the Taylor and Francis share to be less significant because while it has the largest share in law journals, that actually amounts to only 10% of the journals [26]. Moreover, we found that the top 10 biggest publishers account for more than half of all the journals in political science so we can say that the market is significantly centralized in terms of the ownership of Scopus journals, with a specific position for Taylor and Frances. Even more notable is that the journals of the top ten publishers receive more than 80% of the publications that means that they have the most prestigious journals of the field and thus the journals of these giant publishing houses have the most significant impact on the development of the field [18].

The geographically centralized nature of political science publishing is even more evident when we take a look at the national diversity of the most prestigious journals that are indexed as Q1 journals in Scopus. Our results show that the UK, the US, and Western Europe were the exclusive owners of the Q1 journals until 2010, but non-Western Q1 journals still only amounted to around 4% in 2022. Most journals in this top category are published in the UK, which has 62% of Q1 journals in political science—three times more than the US and six times more than Western Europe. With this, we can rightfully say that the UK has the single most powerful position in elite political science publishing, followed by the US and Western Europe, and other world regions are literally invisible amongst the Q1 journals.

When it comes to the emerging or less established journals, we can see a more nuanced picture with the participation of world regions beyond the Western world. Specifically, Eastern Europe, Asia and Latin America now publish a lot of Scopus indexed journals (more than 110 together) but there are only five in the highest quartile (Q1). In other words, regions beyond the Western world succeeded in terms of productivity—they publish a lot of journals—but still failed to develop in terms of impact, because, due to their limited number of citations, their journals are indexed in lower quartiles.

While the non-Western world regions lag behind the Western world in terms of impact, they perform much better in terms of open access publishing. Similarly to the patterns of law publishing [26], non-Western regions publish many more journals in open access than do their Western counterparts. While the overall share of open access publication grew significantly from 2000 to 2002 (from 5 to 20%), this development is very different across both world regions and journal prestige. In terms of geography, the most developed open access market is in Latin-America, followed by Eastern Europe and Asia, but only 4% of British journals were published in the open access model in 2002. Moreover, in the case of the most prestigious journals (Q1), the proportion of open access periodicals is much lower (14%), and as most of the Q1 journals are published in the UK, we can add a geographic variance to the prestige variance. In other words, the most significant trend in political science regarding open access publishing is that open access journals are typically lower ranked and published outside the Western world. However, while this trend seems to be persistent in the analyzed period, the number and amount of open access journals is emerging in all the analyzed world regions, with the least development in the UK and the US. This trend can be explained—at least partially—that in Latin America, Asia, and Eastern Europe—but even in Western Europe—Scopus-indexed academic journals are typically younger than the established American and British journals, and in many cases—especially in Latin-America and Eastern Europe—are published by nonprofit university publishers. However, as open access publishing is the subject of an ongoing and widespread scholarly debate within both academia and the publishing industry, we can assume that the share of open access journals will continuously rise in the next couple of years, even in the case of the most prestigious journals [28].

When we turn to the most prolific countries in terms of journal authors, we found that, while the US is only ranked second amongst the countries with the most journals, it has the leading position amongst journal authors across the analyzed years. The trends we found are very similar to the trends that former studies found [13, 16, 18, 26], as authors from English speaking countries publish the most papers in political science journals. However, a more detailed analysis found interesting evidence of regional trends, especially in the case of India, Russia and China, and with them, in the case of the BRICS region. Perhaps because of its colonial past, India is constantly amongst the most prolific countries in political science, despite being in other subcategories in Scimago, India is typically not amongst the most productive countries and focuses more on engineering and computer science. In the general social science category, India is not amongst the top ten countries in Scopus, however, in the political science subcategory, it had the third position in 2000, 2010 and 2015, and now it has fourth position right after the US, the UK and Russia. There could be a variety of possible explanations on why India has a leading position in political science publishing. First, India is a multicultural country with a complex political landscape that includes federalism, regional identities, caste dynamics, and religious diversity. This context provides Indian researchers with rich opportunities to explore and analyze various aspects of political science, such as electoral politics, identity politics, federalism, and social justice. Moreover, India has strong historical, political and policy ties to the Western world and especially to the UK, so the Indian political processes (such as the development of democracy, multiculturalism, etc.) can be easily related to Western political issues, and it makes it possible to conduct comparative research across Western and Indian political cultures. In international journals, sometimes it can be challenging to prove why national political issues have international importance, so the self-evident international ties make it easier for Indian political science researchers to publish their papers for international audiences.

Another significant trend is the rapidly growing Russian participation in political science journals. Our results show that Russian authors were not represented amongst the top publishing countries until 2015, when they held 8th position, and now they are the third most prolific authors behind the US and the UK in political science that puts Russia in a distinguished position in the international network of political scientists. Evidently, Russia has a very important role in global affairs and Russian research often focuses on topics such as Russian foreign policy, Eurasian integration, energy politics, and security studies, which—being very interesting for the international audiences—contribute to the country's prominence in political science publishing. However, the Russian presence was not significant before 2015, so the importance of the country cannot be the sole explanation. While we do not have the analysis that could help us to explain the emerging Russian presence, there can be some tentative explanations. First, the pressure to publish in English language international journals might make Russian political science researchers put more emphasis on their international profile. Second, Russia managed moreover, to get some Russian journals onto the Scopus/Scimago list: while there were no Russian journals in Scimago in 2010, there were 15 journals in 2022 that might also have led to a more visible presence for Russian authors. Third, the Eastern European presence in political science publishing is rapidly growing with 57 journals in 2022, and we can assume that they favor Russian researchers more than Western journals as they are historically and geopolitically more related. Finally, as a result of the Ukrainian conflict, Russia has become more interesting to the international political science discourse, which might have made it easier for Russian political scientists to publish their research in international political science journals.

The last trend that we would like to mention is China, which has a growing presence in international publishing in political science. China has been the second-largest country in terms of R&D expenditure and accounts for more than twenty of global science and engineering publications [29]. However, research shows that in social sciences China does not have the same level of influence as in natural sciences, due to several factors such as imperial legacies, Confucianism, or the Western cultural hegemony in global academia [30]. While research shows that China implemented policies to influence international publishing patterns, its long-term impacts on China’s international engagements, publications, and collaborations remain uncertain [31]. Our study shows that, at least in political sciences, the Chinese science policy led to some success as China appeared amongst the most prolific countries in 2022.

Regarding our second research question, we also explored significant trends in both internationalization and international collaboration. In political science publishing, the international process is continuously evolving, but it holds mainly for the Western countries, as there is no significant improvement regarding internationalization in Russia and India that typically publish papers without international collaboration. From this, we can conclude that the improving internationalization of Western countries is the consequence of their cooperation with each other, and the internationalization process has not resulted in a geographically diverse field of political science. Indeed, our network analysis clearly shoes that the political science publishing field has a strong center within the network that consists of Western countries only. The strongest ties are between the UK, the US, and other English-speaking countries such as Canada and Australia, together with some economically well-developed European countries. Beyond the Western center, there are regional hubs for all world regions, except the Middle East and Africa that are represented only through their most “Westernized” countries, namely Turkey and South Africa. The Latin-American hub is established around Brazil, the Eastern European hub is around Russia, China and Japan have a loose set of Asian countries that cooperate with them. However, these semi-peripheral hubs are not just slightly disconnected from the Western center, but also more or less isolated from each other.

This semi-peripheral positionality shows that, even if need for de-Westernization, de-centralization and the diversification of academic knowledge production are frequently expressed in the literature, the publishing field is still Western-centric where English speaking western countries define the picture of the discipline. As we have seen, the vast majority of journals are published by the West, and most of the political science articles are written by Western authors, or increasingly frequently, in the cooperation of Western authors from different Western countries. One explanation could be—besides the western hegemony in academic publishing—that the language of international journals is still English, so authors from non-English speaking countries are in a worse position when it comes to publication. Our results also show that other cultural features of different world regions can be important when it comes to international cooperation in political science. One of them is language: our findings prove that world regions with the same or similar languages—typically Iberoamerican countries—cooperate with each other very frequently, and, at least partially, it could be a consequence of the shared Roman languages (Spanish and Portuguese). A less visible example is the case of Germany and Austria which share the German language and the cooperation between these two countries is significant. Another important feature is culture because we can see that Asian countries collaborate each other quite often, and in terms of the number of the participating countries, the Asian hub is the most populous with the participation of ten Asian countries. Finally, besides language and culture, a common historical background can lead to frequent collaboration, too. In the case of Eastern European countries, there is neither a common language, nor a common shared culture, but these countries share the post-Soviet legacy that makes them comparable in terms of democratic development, political history and even in terms of academic internationalization.

In sum, our findings show that the publishing field in political science is still lead by a Western core that holds most of the journals, and its influence is extremely high on the level of the most prestigious journals that are located almost exclusively in the Western countries. While there is an improvement in terms of geographical diversity, world regions beyond the Western world tend to create semi-isolated hubs and cannot challenge Western centrality in publishing academic research in international journals. However, in the last few years, Russia, India, and China started to gain significant visibility in the field, thus future research should focus directly on these countries to see if these changes are parts of a general trend towards decentralization or just episodic phenomena.

Notes

These journals were the following: International Organization, Journal of Political Economy, World Politics, American Political Science Review, American Journal of Political Science, International Security, European Journal of International Relations, Journal of Law and Economics, Public Opinion Quarterly, and The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization.

References

Magadán-Díaz M, Rivas-García JI. Publishing industry: a bibliometric analysis of the scientific production indexed in Scopus. Publ Res Q. 2022;38(4):665–83.

Wæver O. The sociology of a not so international discipline: American and European developments in international relations. Int Organ. 1998;52(4):687–727.

Shaw P, Phillips A, Gutiérrez MB. The death of the monograph? Publ Res Q. 2022;38(2):382–95.

Sarin S, et al. Uncovering the knowledge flows and intellectual structures of research in technological forecasting and social change: A journey through history. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2020;160:120210.

Mas-Tur A, et al. Half a century of quality & quantity: a bibliometric review. Qual Quant. 2019;53(2):981–1020.

Mora L, Bolici R, Deakin M. The first two decades of smart-city research: a bibliometric analysis. J Urban Technol. 2017;24(1):3–27.

López-Rubio P, Roig-Tierno N, Mas-Tur A. Regional innovation system research trends: toward knowledge management and entrepreneurial ecosystems. Int J Qual Innov. 2020;6(1):4.

Donthu N, et al. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: an overview and guidelines. J Bus Res. 2021;133:285–96.

Palmatier RW, Houston MB, Hulland J. Review articles: purpose, process, and structure. J Acad Mark Sci. 2018;46(1):1–5.

Khan MA, et al. Value of special issues in the journal of business research: a bibliometric analysis. J Bus Res. 2021;125:295–313.

Fisher BS, et al. How many authors does it take to publish an article? Trends and patterns in political science. PS: Polit Sci Polit. 1998;31(4):847–56.

Lowi TJ. The state in political science: how we became what we study. Am Polit Sci Rev. 1992;86(1):1–7.

Mas-Verdu F, et al. A systematic mapping review of European Political Science. Eur Polit Sci. 2021;20(1):85–104.

Shor E, et al. Terrorism and state repression of human rights: a cross-national time-series analysis. Int J Comp Sociol. 2014;55(4):294–317.

Lehnert M, Miller B, Wonka A. Increasing the relevance of research questions: considerations on theoretical and social relevance in political science. In: Gschwend T, Schimmelfennig F, editors. Research design in political science: how to practice what they preach. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK; 2007. p. 21–38.

Carammia M. A bibliometric analysis of the internationalisation of political science in Europe. Eur Polit Sci. 2022;21(4):564–95.

Needler MC. Political development and military intervention in Latin America. Am Polit Sci Rev. 1966;60(3):616–26.

Giles MW, Garand JC. Ranking political science journals: reputational and citational approaches. PS: Polit Sci Polit. 2007;40(4):741–51.

Chi P-S. Bibliometric characteristics of political science research in Germany. Proc Am Soc Inf Sci Technol. 2012;49(1):1–6.

Kristensen PM. Dividing discipline: structures of communication in international relations. Int Stud Rev. 2012;14(1):32–50.

Maliniak D, Powers R, Walter BF. The gender citation gap in international relations. Int Organ. 2013;67(4):889–922.

Dion ML, Sumner JL, Mitchell SM. Gendered citation patterns across political science and social science methodology fields. Polit Anal. 2018;26(3):312–27.

Leifeld P, et al. Collaboration patterns in the German political science co-authorship network. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(4):e0174671.

Jensen MD, Kristensen PM. The elephant in the room: mapping the latent communication pattern in European Union studies. J Eur Publ Policy. 2013;20(1):1–20.

Metz T, Jäckle S. Patterns of publishing in political science journals: an overview of our profession using bibliographic data and a co-authorship network. PS: Polit Sci Polit. 2017;50(1):157–65.

Christián L, Háló G, Demeter M. Twenty years of law journal publishing: a comparative analysis of international publication trends. Publ Res Q. 2022;38(1):1–19.

Demeter M. The world-systemic dynamics of knowledge production. The distribution of transnational academic capital in social sciences. J World-Syst Res. 2019;25(1):111–44.

Demeter M, Mayor ZB, Jele Á. The international development of open access publishing. A comparative empirical analysis over seven world regions and nine academic disciplines. Publ Res Q. 2021;37(3):364–83.

Xu X. A policy trajectory analysis of the internationalisation of Chinese humanities and social sciences research (1978–2020). Int J Educ Dev. 2021;84:102425.

Xu X. Internationalization of Chinese humanities and social sciences. In: Marginson S, Xu X, editors. Changing higher education in East Asia. London: Bloomsbury; 2022. p. 129–46.

Shu F, Liu S, Larivière V. China’s research evaluation reform: what are the consequences for global science? Minerva. 2022;60(3):329–47.

Funding

Open access funding provided by National University of Public Service. TKP2021-NKTA-51 has been implemented with the support provided by the Ministry of Culture and Innovation of Hungary from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund, financed under the TKP2021-NKTA funding scheme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaiser, T., Tóth, T. & Demeter, M. Publishing Trends in Political Science: How Publishing Houses, Geographical Positions, and International Collaboration Shapes Academic Knowledge Production. Pub Res Q 39, 201–218 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-023-09957-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-023-09957-x