Abstract

The profession of sociologist in Italy has undergone the same ups and downs as the development of the discipline, which since its institutionalisation (which came very late) has always had to fight for autonomy and the search for legitimate recognition as a science within the wider world of social sciences (economics, political science, etc.). This has produced two conditions that have not favoured the construction of a real community of practice of sociologists: on the one hand, a scarce or total lack of cultural legitimization for the the work of the sociologist that is a consequence of a sociology perpetually in crisis and in search of political recognition and influence that has never been achieved; on the other hand, the separation between academic sociologists and professional sociologists which has resulted, for the former, in the analysis, explanation and interpretation (on the basis of different disciplinary paradigms) of sociocultural processes and changes in society, without any real direct involvement (theoretical sociology), while for the latter, in the comparison, measurement, evaluation of observable processes in the context of the social reality of which one is a part (applied sociology). This article focuses on the “lights” and “shadows” of the professional development of sociologists in Italy, starting from the assumption, however, that a regulatory legitimization can never be complete unless a cultural legitimization and recognition is achieved that can consolidate a professional identity that allows differentiation with other “neighbouring” professions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In Italy, the profession of sociologist in Italy has undergone the same ups and downs as the development of the discipline (Mangone & Picarella, 2023) which, since its institutionalization (which came very late), has always had to fight for autonomy and the search for legitimate recognition as science within the broader world of social sciences (economics, political science, etc.). This has produced two conditions that have not favored the construction of a real community of practice of sociologists (Siza, 2019; Wenger, 1998): on the one hand, a poor or total lack of cultural legitimization for the work of the sociologist (Chiarenza, 1993, 1998) which is the consequence of a sociology perpetually in crisis and in search of political recognition and influence never achieved; on the other hand, the separation between academic sociologists and professional sociologists (Minardi, 2019) which translated, for the former, into the analysis, explanation and interpretation (on the basis of different disciplinary paradigms) of socio-cultural processes and changes in society, without real direct involvement (theoretical sociology); while for the latter in the comparison, measurement, evaluation of the processes observable in the context of the social reality of which one is part (applied sociology). This, if for academic sociologists, meant having a legitimacy based on the two main functions performed (teaching and research), for professional sociologists - not having a strong position in the world of professions (as for lawyers or doctors to name just two examples) - meant conquering one’s position in the world of work through a laborious search for cultural and regulatory legitimization (Perino, 2021). And if the first can be achieved (the process is not yet completed) with the construction of a professional cultural identity that takes shape already in university study courses and continues with continuous training; the second was achieved with the approval of the technical standard (‘UNI 11695’ of 2017) of the National Standardization Body (Benvenuti et al., 2020) - national organization homologous to the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) - built in order to clarify the tasks and activities that characterize the professional profile and strengthen the identity of the professional sociologist. We are trying to strengthen this first step towards normative legitimization also with the establishment of the Professional Register of Sociologists: as will be said later, in fact, a bill has been deposited in the Chamber of Deputies with the aim of establishing the register and regulate the profession. On the base of these brief statements, this article intends to examine these dynamics by highlighting the “lights” and “shadows” of the professional development of sociologists in Italy, starting from the assumption, however, that normative legitimization can never be complete if it is not achieved a legitimization and cultural recognition that can consolidate a professional identity such as to allow differentiation with other ‘neighboring’ professions and the construction of a real community of practice (Wenger et al., 2002). In fact, the activities of the sociologist have a connotation of collective and social character and, therefore, can not be the result of the imagination or ingenuity of a single, but often are the result not so much of a community of practice but of a community of resistance (Sivanandan, 1990; van der Velden, 2004): groups of individuals characterized by the spontaneity of both social and professional aggregation, inserted in learning processes and dealing with common themes and with the same needs (the communities, in general and similarly the professional ones, represent the active subject that favors the exchange of experiences and promotes and provokes actions).

Sociology and the Work of the Sociologist Between Objective and Subjective Dimensions

As mentioned in the introduction, the development of the profession of the sociologist is intertwined with the development of sociology inevitably, but above all with the position that sociology has occupied in the Italian socio-political-cultural scenario that, as Mangone and Picarella (2023) argued, they produced with considerable delay the legitimization of the discipline and consequently also the profession of the sociologist and not always with positive effects on society.

Sociology is an instrument of knowledge of the interconnections of the social because it analyzes not so much the specific aspects of society as such but the interactions, the ties and the reciprocal conditioning. This was clarified very well by Sorokin in his essay - published for the first time in 1913 in Russian by the publisher Obrazovanie of Saint Petersburg and republished posthumously in English with the title The Boundaries and Subject Matter of Sociology - where you can read:

To define the field of sociology, as with any science, means to select the category of facts that are the object of its study - in other worlds, to establish a special point of view on a series of phenomena that is distinct from the point of view of other sciences. No matter how diverse the definitions by means of which sociologists characterize the existence of social or superorganic phenomena, all of them have something in common, namely, that the social phenomenon - the object of sociology - is first of all considered the interaction of one or more kinds of center, or interaction manifesting specific symptoms. The principle of interaction lies at the base of these definitions; they are all in agreement on this point, and their differences occur further on, regarding the character and form of this interaction (Sorokin, 1998, p. 59).

This definition of the field of study of sociology appears clear both in the objectives and in the aims of the discipline that must describe the most common forms and stages of development, without claiming to formulate “laws of development” and/or “historical trends”. As Bourdieu argued in his speech for the CNRS Gold Medal, the task of the humanities and social sciences is “the critical unhinging of the manoeuvring and manipulation of citizens and of consumers that rely on perverse usages of science” (Bourdieu, 2013, p. 12) going beyond the questions posed by common sense or the media, which are often configured as induced and not real.

Therefore, the profession of the sociologist and the consequent knowledge produced are configured as a dimension of the reflectivity of the individual that is neither subjective nor structural but correlated to the order of reality of the social relationship (Bourdieu, Chamboredon & Passeron, 1991). And it is precisely on relations, for example, that Bourdieu bases his unitary model. This model, aiming at the conjugation of the “theory of action” with the “structuralist theory”, focuses the analysis not on individual phenomena but on the systems of relations between objects and events. As Wacquant points out “Against all forms of methodological monism that purport to assert the ontological priority of structure or agent, system or actor, the collective or the individual, Bourdieu-affirms the primacy of relations. In his view, such dualistic alternatives reflect a commonsensical perception of social reality of which sociology must rid itself […] Social science need not choose between these poles, for the stuff of social reality — of action no less than structure, and their intersection as history — lies in relations” (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992, p. 15). In summary, for Bourdieu, the “thinking relationally” is at the foundation of the social sciences, and it is precisely this thinking that must lead sociology to be reflective in the sense that it must recognize the limits of the scientific statute of the discipline starting from the distinction between knowledge of common sense and scientific knowledge. In this way we introduce the idea of the “epistemological rupture”, that is the precise definition of the boundaries of social science with respect to common sense while not denying that the persistence of that “spontaneous sociology” of common sense is rooted in social. In fact, sociological knowledge, “is always suspected - especially among conservative circles - of compromising with politics” (Bourdieu, 2013, p. 9), since these knowledges are the result of the work of a subject (the sociologist) which is itself part of society and therefore runs the risk of investing presumptions and prejudices, but the main defense for this danger is precisely the critical interpretation of sociocultural phenomena. In fact, Bourdieu himself makes it clear that “for the sociologist, familiarity with his social universe, is the epistemological obstacle par excellence, because it continuously produces fictitious conceptions or systematizations and, at the same time, the conditions of their credibility. The sociologist’s struggle with spontaneous sociology is never finally won, and he must conduct unending polemics against the blinding self-evidences which all too easily provide the illusion of immediate knowledge and his insuperable health” (Bourdieu, Chamboredon & Passeron, 1991, p. 13). The sociologist is strongly involved in this sort of double role (analyst and object of analysis at the same time), the sociologist does not try to aseptically understand the problems, but is the one who, as part of society, considers himself an active part and, therefore, does not defend himself from society, but tries to make it more “human-scale” through critical reflection (Wacquant, 1989). The work of the sociologist and the sociological knowledge produced are therefore configured in a dual way: on the one hand, they allow for “institutional accompaniment” (public service) which does not mean responding to all the needs of society, but means formulating scientific responses to real problems not with the “solution”, but by proposing possible paths for improving the specific need (Mangone, 2019); on the other hand, they allow the development of a “critical and active citizen” very close to the ideal type of the “well-informed citizen” of Schütz (1946) which, revisited according to current society (Mangone, 2014), seems to advocate the affirmation of a modern citizenship that is no longer configured only as a right, but also as a duty; and for which the constitution of socially approved knowledge - based on responsible forms of freedom that reveal themselves through social reflexivity, a dimension of the individual that is neither subjective nor structural but correlated to the order of reality of the social relationship - becomes priority.

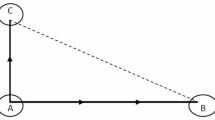

Based on this, we can state that, if all work activities produce effects of an individual and economic nature, for some of them the implications produced can also be of a social and cultural nature and Sainsaulieu (2009) refers precisely to the latter two characters regarding the role of the sociologist. The French scholar states that the problems related to the role of the sociologist cannot be separated from those related to the commitment and intervention of the sociologist in general. Our view is that a clear distinction of the implications of these activities does not exist. There are socio-political implications and personal (biographical) implications. And it can be said without a doubt that this non differentiation of the implications is concrete because social reality consists of objective (objective) and subjective (symbolic) aspects. Sociology is the search for these real connections which are both ‘actions’ (intersubjectivity) and ‘operations’ (organizational structure). The boundary between what is science (think of academic sociologists), profession and social utility is soon overcome. Moreover, the researchers “are ordinary human beings who have dedicated their lives to create knowledge” (Valsiner, 2017, p. 25) are themselves part of sociocultural phenomena. At this point we can no longer talk about the opposition theory-operativity. We must speak of a continuum of interdependencies that goes from theory to operativity, passing through action-research.

It becomes essential to acquire a knowledge that must “get its hands dirty” to read the individual and/or social phenomena, in order to translate the theoretical premises into concrete acts. In this logic, sociology (in particular) and the other sciences of society and humanity (in general) must play a fundamental role in the establishment (first) and maintenance (then) of the integration of these aspects, contributing also to the construction of a responsible working environment, in which each professional with his own knowledge and experience can be directly involved in the choices to be made in relation to the problematic situations that arise.

In the field of sociological work in Italy, this condition is exacerbated by the difficulty that sociologists have to enter fully into the debates on the future of the professions that concern the social sphere, and this is mainly due to two kinds of reasons. On the one hand, we find a twofold fragmentation: the first is that which is recorded among professional sociologists and academic sociologists. The Italian sociologists (as a whole of academics and professionals) failed to overcome the “two sociologies” that Ernest Becker had identified in his book, The Structure of Evil: An Essay on the Unification of the Science of Man (1968): “One is the superordinate science of humanity which calls us to action and to change the world. It is an ideal science concerned with not just ‘what is’ but what ‘ought to be.’ The postmodernists have re-taught us that any version of ‘what is’ contains its own recommendation of ‘what ought to be.’ […] The second sociology is the narrow academic discipline content to color within the lines and seek only journal articles, research grants, and tenure” (Du Bois & Wright, 2002, p. 6). What Becker called the new science (“Science of Man”) should not separate the “facts” from the “values” and had “as its primary task that of changing society, so that it [becomes] a product of human freedom rather than of blind necessity […] a program for analyzing and remedying the evils that befall man in society” (Becker, 1968, pp. 30–31). What Becker proposed was “that sociologists no longer imagine that it suffices ‘to do’ science; that in order to have a science of man, they need only work piling up data (facts), and trying to ‘tease out’ (horrid positivist word) social laws for eventual use… they cannot shun an active option for man as an end. If they continue to do so, they will not have any science” (pp. 367 − 68). Italian sociology - distinguished between academics and professionals - does not fall within Becker’s idea of sociology as “a superordinate science in the service of humanity. To say it is a superordinate science means that it synthesizes the disciplines and then uses that synthesis to forge a shared agreement about how to create a better world” (Du Bois & Wright, 2002, p. 5) while using scientific tools and methods. Italian sociology has never been oriented to the rediscovery of the positive aspects of man and, therefore, has never been seen as a guide for overcoming strictly positivistic models of knowledge (Masullo, forthcoming). And the second is between the “historical core” of the professionals (the first generation professionals that has developed since the 60/70) and the new who live in a more precarious condition; on the other hand, there is the notion of “social mission” (Sainsaulieu, 2009). This shows a change in values. In fact, we have moved from an idea of “humanism” to an idea of “sociality”, the values that seemed to prevail previously were visible and recognizable. “What has replaced them does not have these characteristics, thus the ‘mission’ has become rather a ‘burden without hope’ because of the intangibility of the activities carried out. What we now call ‘social work’ corresponds to what was called ‘work on others’ or ‘work of help yesterday’ (Mangone, 2009, p. 156). The substantial difference is that social work has almost become or is becoming residual and that workers themselves often find it difficult to recognise it, partly because of the poor visibility of this particular type of work, but the problem of visibility is not a problem of form rather than of content and organization; visibility is necessary to legitimize the action and to make known its meaning and usefulness. The problem arises, and also in considerable form, when the sociologist himself does not recognize this role, and does not see himself as such. To favor this condition of lack of perception there is the aspect of the intangibility of the content of their work, social work acts on the relationships of individuals and as such poorly defined and uncertain.

However, the work of the sociologist in Italy has difficulty in combining the system (objective dimension) with individuals (subjective dimension). Regarding the activity of the sociologist, it can be said that it must presuppose a union with knowledge, and this is even more necessary in a scenario in which the complexity increases and the definition of the territory to which to turn the actions is less and less precise and this in Italy is also linked to the process of administrative federalism. The crisis of the welfare state systems and the attempts to define and launch new policies has not prevented the fraying of the legal protections of labour, nor the deterioration of the social fabric that must be reconstructed through the realization of new forms of solidarity for the well-being of citizenship. And it is in this process of reconstruction that lies the work of the sociologist (which can be understood as an intermediate position between the civil and political role of the person). In the practice of his work, the sociologist must pay close attention to all aspects of the transformation of society, and not only those of certain specific sectors, since the action can not be exclusively technical, having already given the understanding of reality and therefore exercise control over it, but it must also contemplate a reflexivity on its own activities.

The sociologist is strongly involved in this double dimension (objective and subjective) and struggles to extricate himself as an analyst and the object of analysis at the same time. The sociologist must take on the role of promoter of the construction of links in the living environments between subjects and initiatives that can not spontaneously get in touch by overcoming the logic that “must help” to encourage the logic of a professional “hub” of the community territorial network.

Recognition of the Profession of Sociologist in Italy

The process of professionalization of the sociologist in Italy is characterized by an uncertain identity and a slow and non-linear evolution that highlight the difficulties of sociology both to make the best use of the skills available, both to provide satisfactory and lasting employment opportunities (Perino, 2021; Luciano, 2013; Rampazi, 2015; Argentin et al., 2015). The problems affecting the profession arise mainly in terms of the lack of recognition of the profession by the world of work and, consequently, in terms of dissatisfaction with new graduates seeking to enter the said market, of those who can not find a suitable place to the professional profile and even those employed sociologists who aspire to get more recognition and protection.

The cultural nature of the institutionalization of sociological studies in Italy lays its foundations at the turn of the 1950 and 1960 s (Mangone & Picarella, 2023). In particular, the phenomenon has been expanding since 1968. For the graduates of the first faculties of sociology the path of public employment is predominantly open, where, however, they are greeted with mistrust both for the different vocation, both for the social image that the sociologist was creating of himself in those years. This absorption by the public sector was not in itself a bad thing. As is pointed out, “the fact that there are state, semi-state, local government officials whose cultural background is dominated by the sociology of organization, political science, social psychology and research methodology, rather than the history of Roman law, ecclesiastical law and criminal procedure, is probably a fact in itself consistent with the need for greater attention of bureaucracy to the substantive aspects of its activity, then to the attenuation of the exasperating ritualism that still characterizes the bureaucratic apparatus” (Statera, 1980, p. 110).

In other words, sociologists proposed themselves in society as subjects with a set of analytical knowledge and methodological and technical skills, as well as relational and communicative skills able to provide advice for the analysis and diagnosis of ‘social problems’ with reference to aggregates of different configurations and consistency. This, through the use of a coordinated set of recognized theoretical knowledge (Social Theory), methodological and technical tools, specific for the observation and measurement of social phenomena (Research Methods) and models and practices of intervention on social organization (Action Research) for the solution of social problems or for the treatment of the subjects and groups involved in it (Social Work) (Minardi, 2019). On the other hand, the formation of an unprecedented demand (of models and techniques of planning and organization of systems of supply and distribution of services for the Welfare that was taking shape in Italy) has progressively identified in the sociologist that set of analytical knowledge and methodological and technical skills, as well as relational and communicative skills with social subjects and organizations, decisive for the growth and articulation of systems of social and welfare provision, adapted to the complexity of social demands. In this sense, the profession of the sociologist seemed to be among those so-called emerging and, in some respects, winning, also and above all if related to the demands for innovation and social reform active within a country differentiated in a socio-economic and cultural sense like Italy. However, with this trend that characterized the Italian context, many other potential outlets for the profession of the sociologist remained closed and there began to be a growing “mediatization” of the discipline (Cesareo, 2001). In common opinion, the sociologist is often another version of the ideologue and on the level of the public image of official culture is not recognized a scientifically autonomous space: the so-called figure of the assault sociologist (Statera, 1982), albeit caricatural, is often associated with the very idea of sociology.

In fact, sociology, at the moment in which it increased its orientation to the applicative dimension to the different worlds of the social, has certainly operated in itself a sort of adaptation to the new context from which came questions of growing interest; in this perspective has developed a methodology of analysis and research focused on quantitative techniques (also thanks to easier access to data processing software) but at the same time it has received the demand for the development and differentiation of qualitative analysis techniques (from observational techniques to more directly semiotic ones). A change of this kind of discipline was followed by other significant changes (Minardi, 2019) that contributed to the enrichment and strengthening of the methodological heritage of the discipline.

In the context of this change, what are the factors that have contributed to produce the figure and profile of the professional sociologist, directly derived from the academic figure? In many places it is emphasized, in fact, how the “extra-university” characterization of the professional sociologist translates into a specialized technical action - which refers to modified theoretical frameworks - and the construction of methodologies of analysis and evaluation more centered on the subject-object of research and its direct involvement in a design of “participatory investigation” (Minardi, 2023). For these reasons, it can be observed that the professionalization of the sociologist is presented as a process that is not built only by external events, but also by a change in the “vocational” structure of sociology. Initially the role of the sociologist was to develop an analytical activity aimed at building a general and scientific social theory; the subsequent criticism of this approach brought the subject to the center of the work of the sociologist, the various concrete phenomena attributable to intersubjectivity, the complex questions elaborated by social subjects in the context of everyday life.

Such a change of strategy has been very relevant to sociology as a science, but also for the sociologist who has been trained on this science and who starts from it to build his own strategy of social work and change in the organizational and communicative systems of the wider social system.

As Minardi explains, “the professionalization of the sociologist seems to fit within a progressive maturation of sociological knowledge and its ‘interests’ that from the traditional centrality of the ‘social system have gradually centered on the ‘phenomenological’ concreteness of social subjects and the relational forms of their actions as well as, of the symbolic mediations they produce” Footnote 1 (2023, p. 8). The centrality of the subject and its living conditions, however, is not enough to explain the professionalization of the sociologist; indeed, the social construction of reality (Berger & Luckmann, 1966) also requires a work of sociological understanding as well, the measurement and weighting of its component variables. “It is not uncommon to see how the professionalization of the sociologist, while stimulated and oriented by sociological frames of qualitative or more specifically phenomenological, it results - and is reduced - often in a set of empirical research actions characterized in a strictly quantitative sense, and in a method of analysis that often makes use of essentially sociographic techniques” (Minardi, 2023, p. 10).

Hence the sociologist’s need for a concrete knowledge of the phenomenon being considered, which does not prescind from the recognition of the subjectivity of the social actors that are a constitutive part of it, but is based on it, identifying the set of relational structures, inter-objective and regulatory-institutional content, on which to intervene to achieve change and development. On the other hand, the possibility of analytically reconstructing and representing in a phenomenological sense the different social phenomena in their relational structures based on intersubjective, and at the same time normative, allows not to have to give up the other ‘vocation’, that is the therapeutic and transformative of sociology.

The Evolution of Normative Legitimization

The symptoms of the start of a decisive path of change have occurred in Italy, starting from the 1980s, when a growing group of sociologists began, through formal and informal actions, to draw the attention of public opinion and the scientific community to problems relating to the social use of sociology and the legal recognition of the profession (Chiarenza, 1993). In 1982 the Italian Association of Sociology (AIS – Associazione Italiana di Sociologia) was founded - in fact the association of academic sociologists - which is the oldest and most structured among Italian associations and which is presented as a meeting place between academic sociologists and professional sociologists (although it will not succeed in this); at the same time we witness the birth of the National Association of Sociologists (ANS – Associazione Nazionale dei Sociologi), with the aim of promoting and recognizing the role of the sociologist. A few years later (in 1990) the Italian Society of Sociology (SOIS – SOcietà Italiana di Sociologia) was born, an association of professional sociologists who will also publish a scientific journal (entitled Sociology and Profession: reflections, themes and proposals) to give national resonance to the scientific debate on professional sociology, the formalisation of the request for legal protection of the profession and the implementation of a code of self-regulation. The goal of the professionalization of the sociologist goes on during the nineties with the birth, in 1996, of the Italian Association of Sociotherapy (AIST – Associazione Italiana di SocioTerapia), and, in 1997, of the Italian Association of Evaluation (AIV – Associazione Italiana di Valutazione). The third millennium will see the birth of the Italian Society of Sociology of Health (SISS – Società Italiana di Sociologia della Salute) in 2002 and, much more recently (in 2015) the Italian Association of Dynamic Sociology (AISoD – Associazione Italiana di Sociologia Dinamica) and, in 2016, the Association of Italian Sociologists (ASI – Associazione Sociologi Italiani) which - at the time this contribution is being written - is the only association recognized by the Ministry of Enterprises and Made in Italy (MIMIT – Ministero delle Imprese e del Made in Italy) for issuing the professional qualification certificate for the services provided by its members, guaranteeing training initiatives; has a code of ethics and a price list of services to guarantee the client and protect the professionalism of the sociologist.

As you can guess, over the last half century or so, various bodies have been created to protect the profession, some with more general social objectives, others have more specific spheres of competence. And this shows that if it is true that there are areas in which the figure of the sociologist has many critical issues, it is equally true that there are also areas of greater protection and recognition, especially as regards the private sector in its various degrees of structuring. All these associations, in fact, represent the privileged areas where to address the issue of professional recognition, since they are structured associations, which, among their associative objectives, have to offer guarantees of identity and professional recognition.

In the field of the liberal profession, the sociologist can work in a creative and experimental way in the area of research-intervention, dissemination, teaching, change and improvement innovation, etc. enjoying a creativity, a dynamism and a professional freedom, not easily applicable within structured contexts, which allow him to make full use of his knowledge and skills. In this case, in addition to referring to the associations and the aforementioned rules, he enjoys tax recognition that allows him to work in full respect of his professionalism having access, at the end of his career, to pension treatment, like any other professional. There is, in fact, the tax categoryFootnote 2 (72.20.00: research and experimental development in the field of humanistic social sciences) which includes systematic and creative studies undertaken in the field of social sciences and humanities aimed at enriching the existing knowledge stock and improving its use (Rossetti, 2022). Very recently, then, a bill was presented (Act No. 1338Footnote 3) for the organization of the profession of sociologist with the establishment of the Order of SociologistsFootnote 4 and for the definition of a figure that is recognized for role, space, specialization and responsibility. This was presented (23 November 2023) at a press conference in the Chamber of Deputies. The motivation behind this bill is dictated by the evidence that sociology can be interpreted as that discipline that helps to better know the dynamics of everyday life and that has accompanied the evolution and growth of today’s society. In Italy, this has had a great value also in the health field, so much so that the figure of the sociologist is expected in the staff of local health units since 1978, the year of the establishment of the National Health System (SSN – Sistema Sanitario Nazionale). Sociology offers, in fact, a decisive contribution in understanding phenomena and keeping communities together, especially in difficult or traumatic moments and the relevance to the health theme is due precisely to the fact that health is always an interest and a collective good. For example, the skills of the sociologist can be extremely important in one healthFootnote 5 holistic vision to read needs, understand complexities and plan with good policies new development models. By virtue of Law 4/2013, the sociologist is among the non-regulated professions and from 2017 can also count on the technical standard ‘UNI-11695’, by National Standardization Body (Benvenuti et al., 2020) - which defines the requirements of competence, skills and knowledge of the professional sociologist. In particular, then, also in 2017, the most specific figure of the “sociologist of health”Footnote 6 has been inserted in all respects in the area of the socio-sanitary professions under Law 3/2017 (so-called Lorenzin Law, by the name of the Minister) but despite this it has remained in fact missing the first and most important recognition being the only profession among those socio-sanitary to not be equipped with an Order.

The recognition of the sociosanitary function of the sociologist and the integration of his specific role in the legal status of the staff of the National Health System have occurred very recently, on the occasion of the pandemic due to the spread of the SARS-virusCov-2, by means of the Decreto Sostegni Bis of May 2021, freeing the pre-existing classification in the technical role. Nevertheless, in Ministerial Decree no. 77/2022 “Models and standards for the development of Territorial Assistance in the National Health Service” the role of the sociologist does not appear and is never even mentioned, unlike other figures such as psychologists, obstetricians, prevention, rehabilitation and technical professionals, and social workers. Another initiative that deserves to be mentioned concerns the establishment of the “sociology service of the territory” that took place only in a specific territory (the Campania region in Southern Italy) with Regional Law n. 16 of 18 July 2023. The service of territorial sociology introduces in a structured and continuous way the figure of the sociologist in the Zone Social PlansFootnote 7. It is a connecting and interconnecting figure, with specific skills, who, working in the social field, will be able to provide adequate answers and strategies to individual and group discomfort: in particular, with regard to family issues, women in difficulty, the rights of children, elderly people, with disabilities.

It is clear that, over time, the sociologist has never ceased to offer his contribution in social, health and social health services (public and private). An important contribution also supported by the commitment of university education and research that in recent years has increased and deepened the teachings on applied sociology (in particular to social and health systems). However, this has not prevented, over the years, the process of de-qualification of the role and the exclusion of fact from many areas (health but also educational and pedagogical), replaced by figures regulated by professional associations.

The creation of an Order and the establishment of a Register would, therefore, be the guarantee to be able to carry out the profession in the workplace, both public and private, in order to better place, use and enhance strategic skills and skills that the Italian welfare services system cannot do without and that require a process of unique recognition. But also, and above all, a guarantee to stem any tendency to sociologism or sociological minimalism (Cesareo, 2014, p. 5) - which threatens to become increasingly concrete and dangerous for the category - and a source of greater credibility towards the public that wants or should rely on the professional services of a sociologist.

Is There a Community of Practice of Sociologists in Italy?

As Minardi (2019) reminds us, the weakness of the professional dimension of sociology has already manifested itself since the 1990s, when sociology was urged to dedicate strong attention to crucial issues such as healthcare reform, the reform of intervention on the labor market, the development of new tools for regulating migratory flows, national and regional provisions for the organization of social services. Added to this is the fact that the too weak presence of associationist proposals in the sociological field has further weakened the experiences made by sociologists (often very young) who entered the heart of social work.

Probably already starting from this brief consideration, and taking into account the regulatory efforts for the recognition of the profession, which have taken place over the years, we can understand the reason for the failed attempt to build a community of practice of sociologists (Siza, 2019; Wenger, 1998) which had as its cause and effect the poor or total lack of cultural letitimization for the work of the sociologist as well as the separation between academic sociologists and professional sociologists.

A community of practice (CoP) is a group of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly. This is a concept developed by Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger at the end of the last century and has become a fundamental part of social learning theory (Lave & Wenger, 1991; Wenger, 1998). Communities of practice have some characteristics that differentiate them from communities of interest or project teams. They are first and foremost active participation groups, where everyone takes part in community activities, contributing with their skills, resources and questions.

Participatory activity occurs within a common domain, as members of a community of practice are united by a common interest, activity or field of knowledge, which provides fruitful ground for mutual learning. Another element consists of a shared repertoire of practices, routines and protocols useful for achieving the group’s objectives. Finally, members develop a sense of shared identity within the community of practice, which helps create a space in which collaboration and learning can occur and spreadFootnote 8.

It is precisely about these characteristics, and in particular that relating to the sense of identity, that the main difficulties have been found in identifying and building a community of practice for sociologists. The sociological community is too often considered to coincide with the academic community. And this implies that a large and now consolidated area of professional sociologists, who operate in a variety of contexts, is neglected. For sociologists who work in non-academic contexts, the sociological community as a whole rarely provides any support in interprofessional conflicts; at the same time, the sociologist who works in non-academic contexts is unable to face an increasingly differentiated demand for professional services, to include this differentiation through more complex processes of professional inclusion, strengthening the sense of a common origin and training, a solid identity of common fund, capable of directing differentiated training processes. Experts in communication and/or evaluation, pollsters, mediators, experts in relations with the public, crowd into an operational and conceptual field traditionally the heritage of sociologists, further fragmenting the professional fields into a myriad of figures, whose identities and mutual relationships do not appear adequately identified, whose conceptual references are labile, whose skills are often based on a substantially limited set of techniques and operational practices rather than on an organic body of knowledge (Siza, 2013).

About it, Santoro (2011) tries to demonstrate whether Italian sociology can be considered a scientific community or a community of practices by introducing Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of scientific field. Talking about a scientific field instead of a scientific community “[precisely] means breaking with the idea that scientists form a unitary, if not homogeneous, group” (Bourdieu, 2003, p. 62). Intellectual life, including that which takes place within the boundaries of science, is made up of conflicts and disagreements (Collins, 1999). This is not to say that there is only conflict, and never cooperation, or that scientists never act as if they are in a community. But the question is: under what conditions does this happen? In other words, what conditions must be met before an intellectual field can credibly present itself as a “scientific community”? The answer is not easy especially if one considers that the construction of a profession takes place when the professional community, or the sociological community in this case, begins to be aware that different application developments of the knowledge to which reference is made are legitimate and possible, and on this awareness distinct tools and operating paths are built. On this point, Siza (2013) outlines three application developments for Italy. The first consists of teaching, training and research. The University appears to be the place that can best ensure the autonomy of researchers and teachers, and not hinder their critical vocation. In this aspect, an applicative orientation emerges which is not centered on the resolution of a well-defined practical problem (often the sociologist does not simplify the decision-making situation, indeed he frequently increases its complexity) but is aimed at influencing decision-makers and public opinion.

A second side is made up of the academic and/or professional researcher, who carries out studies and empirical research aimed at building a cognitive framework delivered to the decision maker to increase his decision-making capacity. In this second direction, the sociologist produces analyses and informations useful for solving practical problems. A final application direction concerns operations in non-academic contexts and is therefore constituted by the multiplicity of experiences in which the sociologist is entrusted with the decision to formulate a plan, an intervention project, to manage human relations, to decide on the continuation of a service using the results of an evaluation research, to carry out an analysis and an organizational intervention. They are clearly identifiable professional activities, which have precise disciplinary references, organically apply concepts and results and evolve with constant reference to disciplinary developments.

If in the United States sociology, since its origins, has sought its legitimacy as a science and the support of public opinion through the analysis and development of programs of intervention on many concrete social problemsFootnote 9, in Italy the legitimacy of the non-academic role has never been granted: a substantial part of the same sociology, in fact, believes that this discipline should be only formative, that it should be limited to producing knowledge useful to the critical sense of the student and of public opinion, and should not be involved in practical action, in issues of intervention. In this way, not only is knowledge detached from its operational applicability, but the connections between epistemology, research methodology and the practical spendability of sociological knowledge are completely obliterated (Donati, 2010). These observations show that there is no community if this term means a shared space of frequent and continuous social relations and interactions between the academic and professional world; that there is no community if this imagines a shared space of values and ideals, including ideals and values of excellence (Brint, 2001). A community could exist if this means a shared space of practices, provided that these practices do not end up denying or compromising the community space understood in a relational sense and in that normative ideal. In fact, it does not help to define a community of practice, as defined above, the fact that the three components in which the Italian sociological field is articulated (Mangone & Picarella, 2023) have their own social and intellectual hierarchies, their own intellectual and organizational leaders, their own followers, their own specializations or alleged intellectual superiority (Santoro, 2011).

This has profound consequences on communication between the parties, on scientific production (increasingly segmented according to logics that are often not explained by the object of study but attributable to belonging to a certain group) (Akbaritabar et al., 2020), on credibility, the reputation and the “symbolic capital” of the entire discipline, creating a deficit, both compared to other disciplines (political science, economics, psychology and historiography) sia compared to other national sociologies. It is all this that prevents the construction of a real community of practice. Actually, as Siza writes, “Lynd (1936) observed the emergence of a stratification in the sociological community already in the 1930s, identifying the two blocks of academic sociologists and technicians. Both assume that there are continuities and connections between their respective fields of study, but in truth they tend to grow apart: the academics becoming estranged and ignoring any contact with immediate reality, the technicians accepting an often too narrow definition of problems and looking exclusively to resolve them immediately” (Siza, 2019, p. 7).

This separation continues to be profound in Italy today. In many professional environments, bonds, communication and feelings of sharing and belonging to the same community of academics and professionals are missing. This is a paradoxical situation which not only prevents the consolidation of an existing profession, but has clear effects on the credibility and social identity of the discipline, often giving a negative image of its usefulness. Sociologists working in non-academic contexts rarely receive assured support from the sociological community as a whole: a wide range of professional sociologists working in different contexts are overlooked, not equipped with adequate cognitive resources, methods and techniques. The academic community also seems to show little interest in a large group of sociology graduates who have not differentiated technical skills and generic expectations from the profession but wish to undertake professional roles relevant to their skills that relate to their specific and distinguishing training. Within this social group, professional identity is built through mostly nebulous ties and paths, or is put aside as a secondary problem compared to the primary need to find work (Siza, 2019). This large group of graduates, not having the necessary professional awareness, has for many years been the main critical point with regards to emerging associative experiences, professional development paths, possible training paths and inclusion in work projects.

Marginal Reflections

The absence of a community of practice of sociologists, the weak associative forms that do not support sociologists operating in non-academic contexts with regard to interprofessional conflicts, and the ambivalence of cultural and normative legitimization, constitute the crucial aspects in the path of development of the sociologist profession in Italy.

In terms of curricular training, the figure of the sociologist in Italy is still strongly connected to the courses within the faculties of sociology and political science, while post-curricular training both inside and outside the universities presents a plurality of proposals that increase the uncertainty of the profile in professional terms, even if they accentuate the interest in the technical and methodological aspects: “in recent years there has been a proliferation of the offer of occupational and professional profiles that we would define as ‘unlikely’; many of these not only did not correspond to employment demands in the local and national job markets, but even contrasted with the restrictive, decidedly self-referential logic of the categories equipped with professional self-regulation regulations” (Minardi, 2019, p. 26). In fact, during this period we are witnessing in Italy, not only the growth and institutionalization of professional profiles attributable to psychology and social service (with the establishment of the relevant professional orders and colleges), but also the progressive formation of new figures who are characterized by their function of social and cultural mediation (such as the cultural mediator or the social manager).

The attempts to build participatory and widespread communities of practices and profiles of the work of the sociologist in the italian reality date back, as we have seen, to many years ago without, however, gathering support and consequently favoring the dispersion of experiences, the lack of recognition of the profiles of sociological work, the consolidation of experiences, the sharing of methodologies and techniques, the renunciation of innovation in knowledge and professional practices. Indeed, we have witnessed a succession of aggregations of sociologists who, starting from the most general interests, then focused on the areas of greatest extension of applied sociologies (social and health policies, the labor market, the migratory phenomenon, corporate communication). The facts show that in the professional community of sociologists (contrary to what happened for other professions that followed the same path) the possibility of forming a single community has not been seized, due to the resistance of the professionals and the attitude of the academy, which tends to perceive as intrusive the presence of some certifying body (Perino, 2021). For these reasons and to avoid nullifying the work carried out so far, it would be desirable for community collaboration between professional associations, universities and the labor market to be intensified, in order to be able to promote the aforementioned bill, raise awareness of the knowledge of the technical standard, share information relating to the demands and difficulties of the labor market, create operational synergies in the training field.

In this scenario, an important role should be taken on by professional associations which, as already specified in Law 4/2013, should become not only important points of reference for the orientation and support of their members but also places where discussions and compares the specific fields of action of the profession, the knowledge and skills that the sociologist needs to be a reliable professional, the improvement of professional profiles and training offers, in close collaboration with the academic world, which is often too distant from the world of work (Perino, 2014). In other words, in order to enhance the sociologist’s skills and strengthen his professional identity, we should work on several fronts: (a) on the training front to make qualifications more professional; (b) on the labor market front to spread knowledge of the discipline and promote the employability of sociologists in various sectors; (c) on the front of cultural and normative legitimization. The 2017 ‘UNI’ technical standard was certainly a very useful tool to intensify the process of change that resulted in the bill of 27 July 2023 regulating the profession. A process that has seen an acceleration in the light of some recent events that have especially affected sociologists who work or will work in the health and socio-health sectors: the enactment of Law 3/2018 which, in addition to completing the regulatory framework of twenty-two professions in the healthcare sector, established the area of social and healthcare professions and also included the sociologist in it; the inclusion of socio-health professions in the legal status of National Health System staff, in implementation of the aforementioned law. The “Sostegni bis” decree of May 2021, in fact, in an attempt to recognize and enhance the commitment of some professional figures (social workers, educators, social-health workers, sociologists) who have been on the front line in the Covid health emergency − 19, seems to want to remind you that it is necessary to clarify the activities, work opportunities and recognition of some social professions, including that of the sociologist (Perino, 2021). And the current bill must also take into account the so-called Covid Age and, in general, the complexity of the processes underway, particularly in the social field, and the fact that within these new scenarios employment profiles and professionals that have been present for some time, but demands for new skills are also being generated, new skills with a stronger social orientation, new languages and communication sets capable of bringing together cultural universes, characterized by plurality and multi-ethnicity.

But above all it aims to be an attempt to overturn a situation which for years has seen the prevalence of weakness, precariousness and instability of associative experiences and which today aims to encourage the formation of a sharing of interests and representation of ways of operating, such to make possible the affirmation and visibility of doing the so-called “sociological work” (Minardi, 2019, 2021).

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Notes

At the same time Minardi (2023) observes that the current professionalization of the sociologist does not necessarily also mean “professionalization of sociology”. The current development of schools and addresses of qualitative Sociologies, in fact, does not in itself involve the change of the “theoretical” qualification and the position of “analytical science” that sociology has developed in the course of its functionalist tradition. Moreover, the urge to reconnect theoretical-interpretative imagination and history, masterfully expressed by C. Wright Mills, is not invalidated, nor is the position that A. W. Gouldner has attributed to sociology as “reflective science”: a science that, practiced outside university institutions, would lose the criticality that must characterize it permanently, precisely as a “science of social”.

In Italy, the ATECO code is an alphanumeric combination that identifies an economic activity. The letters identify the economic macro-sector, while the numbers (from two to six digits) represent, with different degrees of detail, the specific articulations and subcategories of the sectors themselves. With ATECO codes it is possible to classify economic activities for statistical, tax and contribution purposes.

The first draft of the Bill was submitted to the Chamber of Deputies on 27 July 2023 signed by Mr Ilenia Malavasi (Democratic Party) and co-signed by Mr Marco Furfaro (Democratic Party). The presentation, in addition to Malavasi and Furfaro, was attended by Rocco Di Santo, president of the Italian Society of Sociology of Health; Patrizia Magnante, president of the Italian Society of Sociology; Francesco Antonelli, president of the Research Council of the Italian Association of Sociology; Pietro Zocconali, president of the National Association of Sociologists; and Saverio Proia, sociologist, former director of the Ministry of Health.

A first Bill on the initiative of senators Brescia, Pellegatti, Bettoni, Brandani and Taddei proposing the establishment of the Order of Sociologists was communicated to the Presidency of the Chamber of Deputies on 15 May 1992 (n. 203/1992). Subsequently, a new parliamentary text on the organization of the profession of the sociologist was approved by the Chamber of Deputies on 8 July 1998, but never completed its approval process in the Senate (the second chamber of approval of the laws in Italy).

One Health’s holistic vision, a health model based on the integration of different disciplines, is based on the recognition that human health, animal health and ecosystem health are inextricably linked. It is officially recognized in Italy by the Ministry of Health, the European Commission and all international organizations as a relevant strategy in all areas that benefit from collaboration between different disciplines (doctors, veterinarians, environmentalists, economists, sociologists, etc.). One Health is an ideal approach to achieving global health because it addresses the needs of the most vulnerable populations based on the intimate relationship between their health, the health of their animals and the environment in which they live (https://www.iss.it/one-health).

The need to create a figure who was specialized in the analysis of the need for health (the sociologist of health, precisely) was born when Health in Italy became “public”, with the establishment of the National Health System. At the same time, over the years, the health sociologist has also made his mark in other contexts, in response to the growing privatization of certain sectors of the system: cooperatives, private social sector, third sector - which seem to require not only “agents of assistance” but real social planners, able to relate the structures of the social protection offer with the genetic factors of social demands - are the contexts in which today finds a more favorable professional placement.

The Zone Social Plan is a programmatic document with which the Italian Municipalities, in agreement with the Local Health Unit Company, define the services to be provided during a year.

Structured in this way, communities of practice, when well managed, can be extremely effective in facilitating learning, knowledge sharing and professional development. However, there are situations where communities of practice may encounter difficulties or not function as intended. Some reasons why this might happen include: (a) lack of active participation; (b) lack of clear objectives; (c) communication problems; (d) absence of effective leadership; (e) inadequate size and diversity; (f) changes in community organization or structure; (g) lack of resources; (h) changes in external contexts.

During the work of the annual conference of the American Sociological Association in 1962 - dedicated to the usefulness of Sociology - the plurality of occupations of the sociologist was documented, its use in industry, in the military apparatus, in public administration, in non-profit organizations, as decision-makers, not only as teachers or researchers (Lazarsfeld et al., 1967). In recent decades there have been further developments in sociological practice in terms of the connection between theory and practical interests, with the introduction of applied sociology courses in university programs (Siza, 2013), with the definition of broad agreements between professional sociologists and sociologists academics.

References

Akbaritabar, A., Traag, V. A., Caimo, A., & Squazzoni, F. (2020). Italian sociologists: A community of disconnected groups. Scientometrics, 124, 2361–2382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03555-w.

Argentin, G., Decataldo, A., & Fullin, G. (2015). Gli esiti occupazionali dei laureati in Sociologia [The employment outcomes of graduates in sociology]. AIS Journal of Sociology, 6, 115–128.

Becker, E. (1968). The structure of evil: An essay on the Unification of the Science of Man. G. Braziller.

Benvenuti, L., Bruni, C., Magnante, P., & Perino, A. (2020). La Norma Tecnica UNI 11695:2017: opportunità e sfide [The technical standard UNI 11695:2017: Opportunities and challenges]. Sociologia Italiana, 15, 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1485/2281-2652-202015-5.

Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The Social Construction of reality: A Treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Anchor Books.

Bourdieu, P. (2003). Il Mestiere Di Scienziato. Corso Al Collège De France 2000–2001. Feltrinelli.

Bourdieu, P. (2013). In praise of sociology: Acceptance speech for the gold medal of the CNRS. Sociology, 47(1), 7–14.

Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. (1992). An invitation to Reflexive Sociology. The University of Chicago Press.

Bourdieu, P., Chamboredon, J. C., Passeron, J. C. (1991). The Craft of Sociology: Epistemological Preliminaries. (R. Nice, Trans.). Walter de Gruyter. (Original work published 1968).

Brint, S. (2001). Gemeinschaft Revisited: A Critique and Reconstruction of the Community Concept. Sociological Theory, 19(1), 1–23.

Cesareo, V. (2001). L’istituzionalizzazione degli studi sociologici in Italia [The institutionalization of sociological studies in Italy]. Sociologia E Ricerca Sociale, 66, 107–114.

Cesareo, V. (2014). La qualità Del sapere sociologico in Italia: Una riflessione [The quality of sociological knowledge in Italy: A reflection]. Studi Di Sociologia, 1, 3–6.

Chiarenza, A. (1993). Legittimazione Culturale E controllo della professione di sociologo [Cultural legitimization and control of the sociology profession]. Sociologia E Professione, 11, 5–19.

Chiarenza, A. (1998). La Deontologia professionale: Un’analisi sociologica [Professional ethics: A sociological analysis. In E. Minardi (Ed.), L’etica Nella Sociologia E nel lavoro sociologico (pp. 159–169). Homeless Book.

Collins, R. (1999). The sociology of philosophies. A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Harvard University Press.

Donati, P. (2010). Sulla Sociologia italiana [On Italian sociology]. Il Mulino, LIX(450), 663–666.

Du Bois, W., & Wright, R. D. (2002). What is humanistic sociology? The American Sociologist, 33(4), 5–36.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511815355.

Lazarsfeld, P., Sewell, W. H., & Wilensky, H. L. (Eds.). (1967). (Eds.). The uses of sociology. Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Luciano, A. (2013). Professione sociologo: C’è un futuro per i laureati in Sociologia? [Sociologist profession: Is there a future for graduates in sociology?]. AIS Journal of Sociology, 1, 133–140.

Lynd, R. S. (1936). Knowledge for what? The place of social science in American culture. Princeton University Press.

Mangone, E. (2009). Il lavoro sociale del sociologo tra dimensione oggettiva e dimensione soggettiva [The social work of the sociologist between objective and subjective dimension]. Salute e Società, VIII(supplement n. 3), 155–160.

Mangone, E. (2014). La Conoscenza come forma di libertà responsabile: l’attualità del cittadino ben informato di Alfred Schütz [Knowledge as a form of responsible freedom: The relevance of Alfred Schütz’s well-informed citizen]. Studi Di Sociologia, 1, 53–69.

Mangone, E. (2019). Limiti E opportunità delle scienze sociali [Limits and opportunities of Social sciences]. Culture e studi del sociale, 4(1), 3–13.

Mangone, E., & Picarella, L. (2023). Sociocultural context, reference scholars and contradictions in the origin and development of sociology in Italy. The American Sociologist. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12108-023-09604-0.

Masullo, G. (forthcoming). The Phases of Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Italian Sociology: Institutionalisation, social engagement, and Emerging Problems. The American Sociologist.

Minardi, E. (2019). Sociologia Accademica E Sociologia professionale [Academic sociology and professional sociology]. Homeless Book.

Minardi, E. (2021). Quale sociologia, quale professione? [Which sociology, which profession?]. Intervista di G. Piscitelli, 4 maggio 2021, https://sociologiaclinica.it/quale-sociologia-quale-professione/.

Minardi, E. (2023). La professione del sociologo di fronte allo sviluppo ed alla crisi del sistema sanitario [The sociologist’s profession in the face of the development and crisis of the healthcare system]. Unpublished manuscript.

Perino, A. (2014). Verso La Certificazione della professione sociologica [Towards the certification of the sociological profession]. AIS Journal of Sociology, 4, 125–135.

Perino, A. (2021). Il malessere della sociologia professionale tra problematiche, aspettative, opportunità e occasioni mancate [The malaise of professional sociology between problems, expectations, opportunities and missed opportunities]. Quaderni Di Sociologia, 85- LXV, 155–163. https://doi.org/10.4000/qds.4539.

Rampazi, M. (2015). Una crisi salutare? Qualche considerazione sulle criticità della professione sociologica, oggi [A healthy crisis? Some considerations on the critical issues of the sociological profession today]. In Perino A., Savonardo L. (Eds.), Sociologia, professioni e mondo del lavoro (22–35) Egea.

Rossetti, F. (2022). La consulenza sociologica: una storia personale, tra promozione e prevenzione [Sociological consultancy: a personal story, between promotion and prevention]. https://sociologiaclinica.it/la-consulenza-sociologica-una-storia-personale-tra-promozione-e-prevenzione/.

Sainsaulieu, I. (2009). Il coinvolgimento del sociologo nel suo oggetto: Il caso del lavoro sociale, sanitaria e di cura [The involvement of the sociologist in his object: The case of social, health and care work]. Salute e Società, VIII(supplement n. 3), 133–148.

Santoro, M. (2011). Esiste una comunità scientifica per la sociologia italiana? [Is there a scientific community for Italian sociology?]. Rassegna Italiana Di Sociologia, 2, 253–299. https://www.rivisteweb.it/doi/10.1423/34988.

Schütz, A. (1946). The Well-informed Citizen. An essay on the Social Distribution of Knowledge. Social Research, 14(4), 463–478.

Sivanandan, A. (1990). Communities of Resistance: Writings on black struggles for socialism. Verso.

Siza, R. (2013). La professione del sociologo tra sviluppo e diffusione della sociologia [The profession of the sociologist between the development and diffusion of sociology]. Sociologia, 1(1), 167–181.

Siza, R. (2019). The sociologist: A profession without a community. International Review of Sociology, 29(3), 378–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/03906701.2019.1672354.

Sorokin, P. A. (1998). The boundaries and Subject Matter of Sociology. In B. V. Johnston (Ed.), Pitirim A. Sorokin. On the Practice of Sociology (pp. 59–70). University of Chicago Press.

Statera, G. (1980). Società E comunicazione di massa [Society and mass media]. Palumbo editore.

Statera, G. (1982). Problemi della sociologia [Problems of sociology]. Palumbo editore.

Valsiner, J. (2017). From methodology to methods in human psychology. Springer.

van der Velden, M. (2004). From communities of Practice to communities of Resistance: Civil society and cognitive justice. Development, 47, 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.development.1100004.

Wacquant, L. (1989). Towards a Reflexive Sociology: A workshop with Pierre Bourdieu. Sociological Theory, 7(1), 26–63. https://doi.org/10.2307/202061.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511803932.

Wenger, E., McDermot, R., & Snyder, W. M. (2002). Cultivating communities of Practice: A guide to managing knowledge. Harvard Business School Press.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Salerno within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This article is the result of active collaboration and exchange of thoughts and ideas between the authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Both authors consent to the publication of the manuscript in The American Sociologist, should the article be accepted by the Editor-in-Chief upon completion of the refereeing process.

Conflicts of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Martini, E., Mangone, E. Sociologists in Italy Between Cultural and Normative Legitimization. The Failed Construction of a Community of Practice. Am Soc (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12108-024-09613-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12108-024-09613-7