Abstract

Both within and outside of sociology, there are conversations about methods to reduce error and improve research quality—one such method is preregistration and its counterpart, registered reports. Preregistration is the process of detailing research questions, variables, analysis plans, etc. before conducting research. Registered reports take this one step further, with a paper being reviewed on the merit of these plans, not its findings. In this manuscript, I detail preregistration’s and registered reports’ strengths and weaknesses for improving the quality of sociological research. I conclude by considering the implications of a structural-level adoption of preregistration and registered reports. Importantly, I do not recommend that all sociologists use preregistration and registered reports for all studies. Rather, I discuss the potential benefits and genuine limitations of preregistration and registered reports for the individual sociologist and the discipline.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Science is powerful, in part, because it is self-correcting. Specifically, due to replication and the cumulative nature of scientific inquiry, over time, errors are exposed. For errors to be exposed, however, research must be transparent, i.e., research methods (e.g., data cleaning processes, questionnaires, research protocol, etc.) must be made explicit. Without transparency, the replication and comprehensive evaluation of prior research is difficult, and scientific progress may be inhibited (Freese, 2007).

Because accuracy is integral to science, it is perhaps unsurprising that researchers in social and natural sciences are vexed by errors which may result in an inability to verify or replicate research findings. For example, psychologists’ inability to replicate important findings has garnered considerable attention in and outside of academia (Moody et al., 2022). In response, some have claimed that science is in the midst of a replication crisis (Jamieson, 2018). The discussion of this “crisis” generally blames researchers whose findings are non-replicable, portraying them as sloppy, incompetent, or dishonest (Jamieson, 2018). Ironically, due to fear of public shaming, researchers may hesitate to admit to mistakes, thereby making the identification of non-replicability more difficult (Moody et al., 2022).

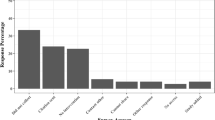

Like these other social and natural sciences, there is reason to believe sociology may also suffer from non-replicability. Specifically, Gerber and Malhotra (2008) reviewed papers published in three top sociology journals: American Sociological Review, American Journal of Sociology, and The Sociological Quarterly. The authors compared the distribution of z-scores in these published papers to what might be expected by chance alone. Without bias, we would expect that z-scores would be about equivalent among statistically significant levels. That is, there would be no greater likelihood to publish a paper with a z-score of 1.96 (and corresponding p-value of < 0.05) than a paper with a z-score of 2.58 (and a corresponding p-value of < 0.01). In fact, if the effect and statistical power are large enough, we might even expect a higher rate of papers to be published at the p < 0.01 than the p < 0.05 level (Simonsohn et al., 2014). In contrast, however, z-scores that are barely past the widely accepted critical value (1.96) and associated alpha level (0.05) are published at a (much) higher rate than would be expected by chance alone. The abundance of barely significant results suggests that, for many claims in sociological research, the strength of evidence may be overstated.

To some extent, a lack of reproducibility is normal and to be expected in research (Shiffrin et al., 2018). It is important, however, that non-reproducible findings are identified so that they do not become the foundation for future research. Additionally, retractions, corrections, and public debate over research findings may damage sociologists’ credibility among the general public (Anvari and Lakens 2018; Hendriks et al., 2020; Wingen et al., 2020). This reputational damage is unfortunate because sociologists have the theoretical and methodological training to weigh in on conversations that are relevant for public policy, workplace practices, and educational guidelines, among others. Furthermore, sociologists’ conclusions are often unpopular, especially to those who have historically held power. For sociological research to have the maximum possible impact, researchers must maximize the actual and perceived quality of their research.

Below, I begin by describing two related practices, preregistration and registered reports, which have been shown to: (1) enhance research quality and replication (Chambers and Tzavella 2022; Scheel 2021; Soderberg et al., 2021; Wicherts et al. 2011) and (2) increase the public’s trust in research (Chambers and Tzavella 2022; Christensen and Miguel 2016; Nosek and Lakens 2014; Parker et al., 2019; Scheel 2021). Next, I discuss the strengths and weaknesses of these practices. Finally, I conclude by discussing the potential implications of adopting preregistration and registered reports for the field more broadly.

Background

Pre-registration

Preregistration is the process of carefully considering and stating research plans and rationale in a repository. When and if the researcher is ready to share them, these plans can be made public. Depending on the type of research, preregistration may include details such as hypotheses, sampling strategy, interview guides, exclusion criteria, study design, and/or analysis plans (Kavanagh & Kapitány, 2019). Preregistration encourages researchers to carefully consider research methods and statistical modeling decisions prior to embarking on a study. As such, preregistration promotes the theoretical and methodological integrity of research.

The “pre” in preregistration is somewhat misleading. Preregistration is not a strict set of rules researchers must follow no matter what (DeHaven 2017; Nosek et al., 2018). When using preregistration, researchers can and should post their research questions, methods, planned analyses, etc. prior to embarking on a research study. Preregistration does not, however, prevent researchers from conducting exploratory or sensitivity analyses. There are moments when the best decision is to deviate from an initial research plan and conduct additional analyses. Preregistration promotes reporting all analyses, while acknowledging which analyses were pre-planned and which were not. This supports methodological transparency and theoretical integrity in the research process.

Registered Reports

Like preregistration, registered reports involve detailing theoretical, methodological, and analytical decisions prior to conducting analyses. Unlike preregistration, registered reports are the basis for peer-review and the acceptance/rejection of a paper (Parker et al., 2019). Specifically, registered reports take place in two stages. In stage 1, researchers submit the content of a preregistration (hypotheses, methods, analysis plans, etc.) to a journal and editors invite reviewers to evaluate the preregistration. At this stage, reviewers are evaluating only the theoretical and methodological rigor of the research plan—not the findings. If the editors’ decision is favorable, i.e., in-principle acceptance (IPA), this means that the journal is committed to publishing the paper, regardless of results. After IPA, researchers carry out their preregistered research plan. Upon completing the study, researchers submit the stage 2 manuscript. For this manuscript, reviewers can only evaluate if the authors adhered to their research plan and made accurate conclusions based on evidence. In Stage 2, reviewers cannot re-evaluate the theory, hypotheses, research plan, etc. (Chambers and Tzavella 2022).

The idea of registered reports have been around since at least the 1960s. In their current form, however, registered reports have only existed since 2012 (Chambers and Tzavella 2022). As of 2022, over 300 journals had adopted registered reports. Because registered reports were started in the psychological sciences, it is perhaps unsurprising that many of the journals that accept registered reports are in psychology. With that said, registered reports have expanded to other social and life sciences (Chambers and Tzavella 2022).

In summary, when adopted by journals, registered reports ensure that papers are reviewed and accepted or rejected based on their preregistered research questions, theory, and methods, rather than their findings (Nosek and Lakens, 2014; Scheel 2021). Since registered reports are a special case of preregistration, in what follows, I will use the term preregistration to refer to both preregistration and registered reports. When speaking of something that is relevant only to registered reports or preregistration, I will clarify.

Types of Preregistration Based on Research Goals

Sociology differs from other social sciences in many ways, but perhaps most notably because of the breadth of research goals/methods that are valued and published within the field. Sociologists commonly use inductive/abductive, deductive, and descriptive approaches to research (i.e., logics). Broadly speaking, by inductive and abductive research, I am referring to research that develops theory. By deductive research, I am referring to the kind of research that tests a priori theoretical hypotheses. Finally, by descriptive research, I am referring to research that neither develops nor tests theory, but that describes patterns that exist in data. Each approach to research (inductive/abductive, deductive, and descriptive) can be done with both quantitative and qualitative data and each is important for scientific progress.

Preregistration takes different forms based on the kind of research; below, I briefly review these idiosyncrasies. Later, I discuss the strengths and weaknesses of preregistration for these different forms of research. While preregistration can be helpful for most forms of research, as I discuss below, it more helpful for some than others.

Inductive/Abductive and Descriptive Research

Inductive and abductive research are focused on the development and refinement of theories (Charmaz, 2014; Charmaz and Thornberg 2021; Glaser and Anselm 1967; Timmermans and Tavory 2012). There are multiple forms of inductive/abductive research, such as ethnographies, interviews, focus groups, analyses of survey data, analyses of administrative or registry data, etc. In contrast, descriptive research is not interested in explicitly developing or refining theory, but instead, presents trends in a consolidated manner. In general, descriptive research involves secondary data analysis, but the sources of that data may vary widely from things like secondary analysis of survey data to word embedding analysis of social media data or news articles.

When preregistering inductive/abductive and descriptive research, researchers will post their research questions and study design (including things such as their interview guides and sampling strategies) on a repository (Haven & Van Grootel, 2019). Because inductive/abductive and descriptive research designs may change in response to findings, researchers are encouraged to update their study design throughout the research process. In updating the study design, the preregistration becomes a living document for researchers to track their study’s evolution.

Deductive Research

Deductive research involves the testing of hypotheses. Like inductive/abductive and descriptive research, deductive research may take many forms, including experiments, textual analysis, analysis of interview data, secondary analysis of survey data, etc. To reduce multiple tests (see discussion below), when preregistering deductive research, researchers will post information about research plans. Specifically, researchers will be asked to report their: research question, hypotheses, sampling strategy, independent variables, covariates, dependent variables, planned analyses, exclusion criteria, sample size, operationalization of variables, etc. Changes to these plans may still be made and documented, but researchers engaged in deductive research are encouraged to stay close to original research plans, justify deviations from those plans, and address statistical concerns associated with such deviations.

Strengths of Preregistration

Scholars from other social science disciplines, including psychology, economics, and political science, have discussed the benefits of preregistration (e.g., see DeHaven 2017; Haven & Van Grootel, 2019; Kavanagh & Kapitány, 2019; Lakens, 2019; Nosek et al., 2018).Footnote 1 Initially developed in the medical sciences and later adopted in social sciences, preregistration was designed to improve deductive, and specifically experimental, research. Preregistration has since been adapted to accommodate multiple methodologies and research goals (Haven & Van Grootel, 2019).

For each type of research, preregistration has different strengths. In what follows, I describe both general strengths of pre-registration (transparency, planning, consideration of prior theoretical knowledge) and strengths that are more specific to research logics (verification of a priori hypotheses, consideration of positionality). Importantly, although preregistration has benefits for all forms of research, it is perhaps most helpful for research designed to test hypotheses, i.e., deductive research, or affect policy (Chambers and Tzavella 2022; Moody et al., 2022).

Transparency

Transparency has two main benefits for scientific advancement. First, a comprehensive picture of the research process may provide useful information for future scholars interested in extending prior work. Second, and perhaps more importantly, an embrace of transparency is associated with stronger research findings and higher quality statistical analyses (Wicherts et al., 2011).

For all forms of research, preregistration promotes transparency about things like study design, theoretical dispositions, and specific data cleaning and analysis plans. By detailing research plans in advance, researchers can make clear what decisions were made before embarking on the study and which decisions were made during the research process. Additionally, preregistration provides a framework in which to report these decisions in detail.

Importantly, however, similar levels of transparency can be implemented with or without preregistration. Journals could change expectations of reporting methodological decisions and extend word counts to encourage a more complete reporting of research practices, including data preparation decisions, testing of model assumptions, or researchers’ positionality. Alternatively, researchers could include such information in appendices. These transparency-enhancing protocols and practices may have once been constrained by the space limitations of physical journals, but are now entirely viable as publishing has moved to a digital format and/or embraced digital tools.

Preregistration’s main advantage over other methods for enhancing transparency is that it is done in advance and contemporaneously updated. Compared to methods in which a researcher reflects on the record and reports details, preregistration may result in a more accurate research record. Specifically, it is easy to unintentionally rewrite a messy research process to seem clear when the findings are known and the data are cleaned. Preregistration shows the process more completely, which may lead to insights, even if not by the original researchers.

Planning and Reduced Error

Perhaps the most helpful feature of preregistration is that it encourages careful planning, thereby reducing error. As noted above, although error is human, errors may slow scientific progress and reduce sociologists’ credibility among the public (Anvari and Lakens 2018; Hendriks et al. 2020; Wingen et al. 2020). There are many reasons why non-reproducible findings are commonly published, and under-identified (Moody et al., 2022). These include things like researchers’ and reviewers’ over-reliance on p-values for determining significance, journals’ desire to publish novel and non-null findings, a lack of transparency, and more rarely, blatant researcher misconduct. Another reason for non-replication is honest researcher error.

Although researchers do their best to think of everything prior to conducting a study, it is easy to overlook important data preparation steps (Lucchesi et al., 2022), or fail to consider possible interaction effects. To reduce such error, preregistration encourages researchers to carefully plan and consider data management and analysis (Olken, 2015; van ’t Veer and Giner-Sorolla 2016). Such planning may reduce error. For example, Desmond et al. (2016)Footnote 2 asserted that after an incident of police violence, calls to 911 from Black communities decreased. Zoorob (2020) reanalyzed the data, demonstrating that the findings in the original study relied heavily on outliers. Responding to this criticism, Desmond et al., (2020) re-analyzed the data, accounting for outliers and including an additional variable, temperature (which is known to affect crime rates due to people spending more time outside rather than in their homes), and found substantively comparable findings to the original study (2016). Even though the authors eventually found compelling support for their initial claims, the debate may have hurt these researchers’, and/or sociology’s, credibility (Anvari and Lakens 2018; Hendriks et al. 2020; Wingen et al. 2020).

Although there is no guarantee, the use of preregistration might have prevented error and resulted in a clearer record. When preregistering the study, researchers are asked how they plan to address any outliers. This question may have prompted Desmond et al. (2016) to consider the role of outliers more carefully. Second, when answering preregistration questions about covariates, Desmond et al. (2016) may have been encouraged to consider the base rate of crime in the original analysis. Without being asked such questions in advance, and by seeing results that conformed to expectations, the researchers may not have been inclined to further question assumptions and findings. With preregistration, these factors may have been considered more carefully. In this way, even when not adopted at the journal-level or made even public, but simply used as a tool for enhancing rigor, preregistration can reduce error and increase reproducibility (Chambers and Tzavella 2022; Nuijten et al., 2016).

White preregistration may be helpful for reducing error, registered reports may be even more helpful. Like preregistration, registered reports may reduce error by encouraging researchers to carefully plan their research methods and analysis. However, by implementing the peer review stage before the execution/completion of a research project, registered reports also ensure additional eyes on these plans. Additional eyes on research plans may increase the potential to catch mistakes before they occur. This is especially true when analyses are quantitative in nature and reviewers are statistically-inclined (Locascio, 2019). For example, reviewers would have had access to all data preparation decisions and may have noticed the inattention to outliers. Furthermore, in evaluating the data analysis plans as opposed to findings alone, reviewers’ attention may have been drawn to the (missing) covariates. As such, the oversight of temperature may have been noticed, and, prior to publication, researchers may have added it in their models. Of course, there is no guarantee that with preregistration and registered reports these errors would have been caught, but they are designed to address these very concerns.

Preregistration and registered reports are not only helpful for quantitative research, but also qualitative research. Specifically, preregistration and registered reports encourages researchers and reviewers to reflect on why researchers made the decisions they did as opposed to alternative decisions. Such reflections may reveal limitations in the current design and/or inspire alternative designs that optimize (rather than limit) the scope and contributions of a study. By revealing such limitations early in the research process, researchers can adjust prior to, or while collecting data (as opposed to merely reporting on them after data has been collected).

Positionality

Positionality describes how researchers’ visible (e.g., race/gender) and invisible (e.g., cultural capital) characteristics affect the way that researchers gain access to different spaces, interact with participants, and analyze data (Atkinson, 2001; Brewer, 2000; Reyes, 2020; Wasserfall, 1993). Because inductive research focuses on researchers’ interpretation of data, positionality is often emphasized in these forms of research. For example, in the methods sections of interview studies, researchers are often expected to state how their social characteristics may have affected how respondents answered interview questions.Footnote 3 Importantly, however, positionality can affect all forms of research. For example, if a researcher is conducting an experiment and only considers some racial/ethnic groups or does not consider race/ethnicity at all, a preregistration form will ask the researcher to explicitly defend their decisions. By asking researchers to consider how their characteristics may be affecting research decisions, preregistration encourages positionality. Furthermore, by pre-emptively and continuously considering positionality during the research process, researchers may make more thoughtful and informed research design decisions (Emerson et al., 2011).

Training

Preregistration may also be a useful tool for training researchers. Specifically, an advisor may encourage students to fill out a preregistration prior to conducting a research project. Just as it does for more seasoned researchers, preregistration asks early career researchers to critically consider and concisely report each aspect of their research design. Perhaps more importantly, preregistration asks students to consider the relationship between their theory and methods. This type and level of consideration is important for all researchers, ranging from undergraduates conducting their first research project to those planning their dissertation (and beyond).

Preregistration is also helpful for advisors. There are a range of different preregistration forms designed to help scholars with different kinds of research. These forms can be used as templates that advisors can use to help advisees get started on research projects. The structure provided by preregistration forms saves advisors some of the work associated with planning the project and provides a clear path for concrete feedback.

Multiple Comparisons: Verification of A Priori Hypotheses

Preregistration is particularly helpful for deductive research. For deductive research, many researchers are working within a framework of null hypothesis significance testing (NHST). In the NHST framework, researchers are generally trying to determine if the difference between groups or the association between variables is meaningful.

Within the NHST framework, there is a single test statistic that is compared to a distribution of test statistics. When working with data, however, there are many decisions that a researcher makes, each creating a potentially different test statistic and/or distribution (Gelman and Loken 2013; Rubin 2017; Wicherts et al., 2016). Depending on the number of these tests, it is likely that at least one will show a statistically significant effect—even if the effect size is rather small and substantively not meaningful (Frane, 2015; de Groot 2014; Szucs, 2016). That is, there is a possibility of Type 1 error. This is referred to as the problem of multiple comparisons or the garden of forking paths (Gelman and Loken 2013, 2014).

Preregistration can ensure researchers are not (consciously or unconsciously) making decisions based on the decision’s implication for findings (DeHaven 2017; Nosek et al., 2018; Wicherts et al., 2016). This is not to say that without preregistration researchers are purposefully searching for a statistically significant effect, running test after test (i.e., p-hacking). Sure, in some instances, p-hacking occurs; however, perhaps more often, researchers may inadvertently engage in motivated reasoning, in which they justify data preparation and modeling decisions based on the implications for hypotheses (Gelman and Loken 2013). Preregistration can prevent such inadvertent reasoning and therefore reduce the likelihood of generating statistically significant—but substantively meaningless—findings.Footnote 4 Indeed, preregistered research papers appear to replicate at a higher rate than traditional papers (Field et al., 2020).

In addition to all the benefits of preregistration, registered reports may go one step further. Specifically, since tenure and promotion are often determined by publication quantity and prestige, and papers with novel and statistically significant findings are more likely to be published, researchers may be motivated to selectively present hypotheses or data that support hypotheses. These motivations pose a problem for scientific inquiry and may incentivize questionable research practices (Dickersin, 1990; Fanelli, 2010; Franco et al., 2014; Gerber and Malhotra 2008). With registered reports, a paper is already accepted on the basis of the question and research methods. This results-masked review means that researchers have little incentive to deviate from plans and engage in questionable research practices.

Reduces the File Drawer Problem

Research is often published based on the extent to which the findings provide new and exciting insights. Consequently, the published record may not be a good reflection of the entire body of research. Specifically, since published research is biased towards larger effect sizes, statistically significant results, and novel findings, the published literature may not provide accurate measurements of effects (Fanelli, 2010; Franco et al. 2014; Gerber and Malhotra 2008). This publication bias does not only exist for quantitative work, but also for qualitative research (Petticrew et al., 2008).

The non-publication of research based on its findings is known as the “file-drawer problem” in which null findings remain filed-away and unpublished (Rosenthal, 1979). The file-drawer problem may result in researchers selectively reporting findings that “fit” a particular narrative (Ioannidis, 2008). As a result, a more nuanced narrative of research findings may be untold (Simmons et al., 2011, 2021).

Some evidence suggests that preregistration may resolve some of the file-drawer problem (Schäfer and Schwarz 2019). Perhaps because research questions and hypotheses are verified in advance, preregistered papers tend to report smaller effect sizes than regular papers (Schäfer and Schwarz 2019). This suggests that journals are perhaps more open-minded to publishing weaker results so long as the results are examining pre-determined questions and hypotheses. This willingness to publish weaker results may resolve some of the file-drawer problem (and associated p-curve, in which findings that are barely past the widely accepted alpha level (0.05) are published more often than we would expect by chance alone (Simonsohn et al., 2014)).

Registered reports may further reduce the file drawer problem. For registered reports, the findings are not known. As such, editors and reviewers should be even less pulled towards the publication of statistically significant results (as opposed to publishing work that evaluates meaningful questions). Indeed, research suggests null findings are published at a higher rate in registered reports than traditional articles (Allen & Mehler, 2019; Scheel, 2021).

Intellectual Property

When transparency is implemented in research, some scholars worry that their intellectual property is at risk. Concerns about intellectual property are particularly relevant for sociologists, as we regularly collect our own data. Collecting data is time-consuming and researchers likely want to publish as much as possible before sharing this data with others.

Fortunately, preregistration helps with concerns about intellectual property. First, researchers can embargo or delay the publication of a preregistration until they are ready to share it with others. The control over when a preregistration is made public is helpful for protecting research plans before they can be conducted.

Furthermore, preregistration is a potential way to protect against plagiarism, or at least prove it when it occurs. Even when not published, when a preregistration is done online, it is time-stamped. As such, preregistration can provide protection from plagiarism by providing verification of when researchers claim a research idea as their own. That is, if another researcher takes an idea and tries to publish it as their own, there will be a record of the plagiarism.

Weaknesses of Preregistration and Registered Reports

Although preregistration is a helpful tool, it is not a panacea for errors in scientific inquiry (Kavanagh & Kapitány, 2019; Lakens, 2019). Indeed, preregistration is not appropriate for all forms of research. Additionally, although preregistration may improve the quality of research, it cannot address all issues within scientific inquiry. Said otherwise, although preregistration may improve research quality, it is neither necessary nor sufficient for guaranteeing it (Pham and Oh 2021). In what follows, I discuss the potential weaknesses of preregistration and registered reports and warn against their uncritical adoption.

Inappropriate/less Helpful for Some Forms of Research

Preregistration and registered reports are not useful for all forms of research. In particular, preregistration & registered reports may not be useful to some researchers who employ grounded theory methods. Specifically, to avoid preconceiving analyses, some—but not all—practitioners of grounded theory strive to suspend prior knowledge, postponing the literature review until after entering the field (e.g., Glaser 1978, 1998, 2001; Glaser and Anselm 1967). As a result, stating assumptions, questions, etc. may not be appropriate for these researchers.

Alternatively, since many researchers—including some who use grounded theory (e.g., Barbour 2003; Charmaz, 2014; Charmaz and Thornberg 2021; Dey 1999; Layder, 1998)—have found it difficult and/or unhelpful to suspend prior knowledge and postpone the literature review (Timmermans and Tavory 2012), preregistration may still benefit researchers who are focused on developing theory. Specifically, when conducting work that is focused on theory development, researchers are likely bringing prior theoretical knowledge (Haven et al., 2020; Haven & Van Grootel, 2019; Timmermans and Tavory 2012). Far from a liability, this prior theoretical knowledge is often considered to be beneficial for theory construction by helping researchers identify gaps in existing theories (Burawoy 1991; James, 1907; Katz, 2015; Timmermans and Tavory 2012). Preregistration encourages researchers to consider prior theoretical knowledge and maintain a contemporaneous record of changes in theoretical dispositions throughout the development of the research project (Haven et al., 2020; Haven & Van Grootel, 2019).

Multiple Comparisons: Over-reliance on p-values

Above, I discussed how multiple comparisons increase the risk of Type 1 error. Although preregistration and registered reports can verify a priori hypotheses and prevent motivated reasoning for multiple comparisons, they cannot change the fact that multiple comparisons may exist (Rubin, 2017). Specifically, each potential decision about how to treat outliers, missing data, etc. can affect the number of potential comparisons. Even if the results of these decisions do not affect which decisions are made, the mere existence of multiple tests belies the logic of the Fisher/Neyman-Pearson/NHST approach. Said otherwise, although preregistration and registered reports may prevent analysis decisions from being influenced by the implications for results, preregistration and registered reports do not prevent analysis decisions “from being influenced by the idiosyncrasies of the data” (Rubin, 2017, p. 8).

In addition to preregistration and registered reports, there are a few ways to address the issue of multiple comparison, including: (1) considering a higher threshold for statistical significance, (2) abandoning the Neyman-Pearson approach (p-values) for Bayesian methods, and (3) the liberal use of sensitivity analyses (Moody et al., 2022; Rubin, 2017). Doing any one of these methods does not necessarily address all concerns about multiple comparisons. Additionally, of the above-listed solutions to the problem of multiple comparisons, preregistration alone is perhaps the least effective in reducing Type 1 error and ensuring the strength of published research (Moody et al., 2022; Rubin, 2017). Rather, research suggests that the liberal use of sensitivity analyses may be the best approach (Frank et al., 2013; Moody et al., 2022; Rubin, 2017; Young, 2018). That is, rather than rely on a single test, researchers can conduct multiple iterations of that test, reporting them all, and coming to a consensus based on this larger body of analyses. Thus, while preregistration can ensure p-values are used as intended, it cannot fix the errors inherent with p-values.

Errors: Coding & Transcription

It is difficult to avoid error. Although some errors occur due to important researcher oversights, many others occur due to everyday human fallibilities, such as coding and transcription mistakes. Indeed, Nuijten et al., (2016) examined papers published in eight major psychology journals between 1983 and 2015 and found that nearly half contained at least one p-value that was inconsistent with its test statistic and degrees of freedom. The researchers attributed many of these to transcription errors, which aligns with other research (Eubank, 2016; Ferguson and Heene 2012; Gerber and Malhotra 2008; Wetzels et al., 2011). Although this kind of error is pervasive and important, unfortunately it cannot be resolved by preregistration. No matter how thoughtful a preregistration, it cannot prevent typos. To reduce the number of such typos, researchers should embrace tools for automation (Long 2009).

Additionally, rather than exposing potential errors in research, preregistration could be used as armor against criticism. As it stands, when errors are identified in research papers (and/or non-replication occurs), the authors of papers face serious consequences and a damaged reputation (Shamoo & Resnick, 2015). Often, this treatment of errors does not distinguish between honest error and misconduct (Resnik and Stewart 2012). As a result, individuals who make honest mistakes may be hesitant to accept their mistakes for fear of the criticism that may befall them (Moody et al., 2022). To defend against such criticism, researchers may use preregistration as a signal of quality, rather than soberly addressing honest mistakes.

This hypothetical scenario is less of a criticism of preregistration than it is a criticism of the treatment of honest mistakes and the researchers who make them. When encountering scientific errors, sociologists must eschew shaming tactics. Instead, we should establish norms of scientific humility, understanding that we are all prone to making similar errors, and treating others’ research (and mistakes) as we would want them to treat ours (Janz and Freese 2021; Moody et al., 2022).

Because error-prevention is equally desirable for journals and authors, journals may consider embracing some of the responsibility of high quality research by, for example, providing pre-publication code review (Colaresi, 2016; Maner, 2014; Moody et al., 2022). This would involve individuals who are employed by the journal examining code in detail. The proposed benefit of this method is that it would reduce error before publication, thereby aligning journal and researcher interests. Although it would require considerable investment, Moody (2022:78–79) notes that “as a discipline, we have decided that other publication processes—copyediting, layout, and bibliometrics, for example—are acceptable and worthwhile. It may be time to include data and methods editing in this process.” To effectively implement these procedures, however, journals would need to have support and incentive (as opposed to mandates and punishment) from other entities, e.g., governmental agencies, funding organizations, academic associations, etc.

Conclusion

In summary, preregistration has promise, but, like any solution, is unable to fully resolve some of the most serious problems that hinder scientific progress. Preregistration may help improve the quality of research by increasing transparency, reducing some forms of error (through planning), preventing questionable research practices, and reducing the file-drawer problem (Chambers and Tzavella 2022; Nuijten et al., 2016; Scheel, 2021; Soderberg et al., 2021). Furthermore, preregistered papers and registered reports have higher rates of replicability and quality than traditional research (Chambers and Tzavella 2022; Nuijten et al., 2016; Scheel, 2021; Soderberg et al., 2021).

Due to its benefits, preregistration may provide an air of legitimacy. Specifically, the use of preregistration has been found to increase the public’s perception of research credibility (Chambers and Tzavella 2022; Christensen and Miguel 2016; Nosek and Lakens 2014; Parker et al., 2019; Scheel 2021).Footnote 5 Unfortunately, reviewers and journals must be careful when assuming that a preregistered paper is inherently more rigorous or accurate than a non-preregistered paper. Preregistration does not reduce Type 1 error caused by data-related idiosyncrasies, does not reduce errors from coding or transcription, and cannot prevent all questionable research practices (Ikeda et al., 2019; Jacobs, 2020; Moody et al., 2022; Pham and Oh 2021; Rubin 2017; Yamada, 2018). Therefore, while preregistration may improve the quality of research in general, it does not guarantee the quality of any one paper. Thus, although preregistration may be a useful tool, if reviewers and journals assume preregistration indicates credibility, preregistration may become a tool for authors to signal but not improve the quality of their work.

Finally, despite the potential advantages for research quality, preregistration and registered reports are often perceived to place high demands on journals and reviewers. An additional layer of bureaucracy and additional content to review may appear to worsen such a problem (Pham and Oh 2021). Importantly, however, some research suggests that registered reports (specifically) may actually reduce the burden to journals by reducing the number of total submissions associated with trying to publish null findings (Chambers and Tzavella 2022). Furthermore, even if registered reports prove to be too labor intensive when adopted at the journal-level, preregistration (as opposed to registered reports) needn’t be adopted at the journal level to be helpful for researchers. As mentioned above, the exercise of filling out a preregistration, even without posting to a public repository, may prevent errors in study design, study implementation, data management, and data analysis (Wicherts et al., 2016). Second, there is considerable evidence that, on the whole, preregistration, registered reports, and similar open-science practices increase research quality (Chambers and Tzavella 2022; Nuijten et al., 2016; Scheel, 2021; Soderberg et al., 2021; Wicherts et al. 2011). Thus, despite the potential high costs, preregistration’s positive effect on research quality may be worth the price of adoption. Specifically, at the individual level, the initial cost is nominal compared to the cost to reputation associated with errors in research (Wagenmakers and Dutilh 2016). At the journal level, multiple submissions, retractions, and corrections are time-intensive, therefore the cautious adoption (or mere encouragement) of preregistration (but especially registered reports) may be helpful, especially when publishing deductive research.

In conclusion, when adopted thoughtfully, preregistration and registered reports may increase the actual and/or perceived quality of research, but do not guarantee it. When used to address non-replication, preregistration acts as an individual solution to a structural problem. Unlike preregistration, registered reports are adopted at the journal level, and therefore may provide additional benefits, for example, by helping address the file-drawer problem. However, due to the diversity of methods and research goals that are valued in sociology, there needs to be flexibility in the adoption of these tools—especially at the journal or discipline-level.Footnote 6 If preregistration is adopted instead of other tools, then researchers, reviewers, and editors may feel better about scientific integrity without substantially improving it. If, however, preregistration is adopted along with other tools or strategies for improving research quality (e.g., pre-publication code review, posting of all materials, more in-depth methods sections), we are likely to see the greatest improvement in research quality (Moody et al., 2022). Thus, preregistration’s true promise lies in the adoption of its goals (i.e., improved transparency, reduced error, comprehensive evaluation of the strength of findings, and a shift in incentive structure), as opposed to an uncritical adoption of its methods.

Data Availability

N/A.

Code Availability

N/A.

Notes

Although preregistration is not widely adopted by sociologists in the United States, the flagship journal for the European Sociological Association, European Societies, recently encouraged scholars to preregister quantitative research (Präg et al., 2022).

I chose this example for a few reasons. First, it appears to be an honest mistake caused by an understandable oversight. Second, the researchers are well-established scholars whose work is highly respected in the field. Although errors in research should not be considered shameful, but rather, human, scholars are often ridiculed for research errors. Due to the high potential for such ridicule, I did not want to choose an example from an early career scholar whose reputation was not yet established in the field.

This is not to say that interviews are only used for inductive research.

Preregistration cannot prevent all questionable research practices and misconduct. For example, to ensure there is something publishable that is also preregistered, researchers could preregister multiple versions of studies and only selectively report these in published papers. Additionally, researchers could preregister findings after results are known, a practice known as PARKing (Yamada, 2018). These practices would, of course, belie the spirit of preregistration, rendering it ineffective (Ikeda et al., 2019; Pham and Oh 2021).

But also see Field et al., (2020).

Fortunately, virtually all journals that adopt registered reports tend to include them as an alternative type of submission, not one that replaces traditional articles (Chambers and Tzavella 2022).

References

Allen, C., & Mehler, D. M. A. (2019). Open Science Challenges, benefits and Tips in Early Career and Beyond. PLOS Biology, 17(5), e3000246. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000246.

Anvari, F., and Daniël Lakens (2018). The Replicability Crisis and Public Trust in Psychological Science. Comprehensive Results in Social Psychology, 3(3), 266–286. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/23743603.2019.1684822.

Atkinson, J. (2001). “Privileging Indigenous Research Methodologies.” National Indigenous Researchers Forum, University of Melbourne

Barbour, R. S. (2003). The Newfound credibility of qualitative research? Tales of Technical Essentialism and Co-Option. Qualitative Health Research, 13(7), 1019–1027. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732303253331.

Brewer, J. D. (2000). Ethnography. Philadelphia, PA: Open University Press: Buckingham.

Burawoy, M. (Ed.). (1991). Ethnography unbound: power and resistance in the Modern Metropolis. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Chambers, C. D., and Loukia Tzavella (2022). The past, Present and Future of Registered Reports. Nature Human Behaviour, 6(1), 29–42. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01193-7.

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing Grounded Theory.

Charmaz, K., and Robert Thornberg (2021). The pursuit of quality in grounded theory. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 305–327. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1780357.

Christensen, G. S. (2016). and Edward Miguel. “Transparency, Reproducibility, and the Credibility of Economics Research.” National Burea of Economic Research Working Paper Series 94.

Colaresi, M. (2016). Preplication, replication: a proposal to efficiently upgrade Journal Replication Standards. International Studies Perspectives, 17, 367–378. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/isp/ekv016.

DeHaven, A. C., & Retrieved (2017). (https://www.cos.io/blog/preregistration-plan-not-prison).

Desmond, M., & Papachristos, A. V., and David S. Kirk (2016). Police Violence and Citizen Crime reporting in the Black Community. American Sociological Review, 81(5), 857–876. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122416663494.

Desmond, M., Papachristos, A. V., & Kirk, D. S. (2020). Evidence of the Effect of Police Violence on Citizen Crime Reporting. American Sociological Review, 85(1), 184–190. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419895979.

Dey, I. (1999). Grounding grounded theory: guidelines for qualitative Inquiry. San Diego: Academic Press.

Dickersin, K. (1990). The existence of publication Bias and Risk factors for its occurrence. Journal Of The American Medical Association, 263(10), 1385–1389.

Emerson, R. M., Rachel, I., Fretz, & Shaw, L. L. (2011). Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes (2nd ed.). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Eubank, N. (2016). Lessons from a decade of replications at the Quarterly Journal of Political Science. PS: Political Science & Politics, 49(02), 273–276. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096516000196.

Fanelli, D. (2010). “‘Positive’ results increase down the Hierarchy of the Sciences” edited by E. Scalas. Plos One, 5(4), e10068. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0010068.

Ferguson, C. J., and Moritz Heene (2012). A vast graveyard of undead theories: publication Bias and Psychological Science’s aversion to the null. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(6), 555–561. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612459059.

Field, S. M., Wagenmakers, E. J., Henk, A. L., Kiers, R., Hoekstra, A. F., Ernst, & Don, R. (2020). The Effect of Preregistration on Trust in empirical research findings: results of a registered report. Royal Society Open Science, 7(4), 181351. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.181351.

Franco, A., & Malhotra, N., and Gabor Simonovits (2014). Publication Bias in the Social Sciences: unlocking the file drawer. Science, 345(6203), 1502–1505. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1255484.

Frane, A. V. (2015). Planned hypothesis tests are not necessarily exempt from Multiplicity Adjustment. Journal of Research Practice, 11(1), 17.

Frank, K. A., Spiro, J., Maroulis, Minh, Q., Duong, & Kelcey, B. M. (2013). What would it take to change an inference? Using Rubin’s Causal Model to interpret the robustness of Causal Inferences. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 35(4), 437–460. doi: https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373713493129.

Freese, J. (2007). Overcoming objections to Open-Source Social Science. Sociological Methods & Research, 36(2), 220–226. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124107306665.

Gelman, A. (2013). and Eric Loken. “The Garden of Forking Paths: Why Multiple Comparisons Can Be a Problem, Even When There Is No ‘FIshing Expedition’ or ‘p-Hacking’ and the Research Hypothesis Was Posited Ahead of Time.” Department of Statistics, Columbia University 17.

Gelman, A., and Eric Loken (2014). The Statistical Crisis in Science. American Scientist, 102(6), 460–465.

Gerber, A. S., and Neil Malhotra (2008). Publication Bias in empirical Sociological Research: do arbitrary significance levels distort published results? Sociological Methods & Research, 37(1), 3–30. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124108318973.

Glaser, B. G. (1978). Theoretical sensistivity: advances in the methodology of grounded theory (2nd ed.). Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. G. (1998). Doing grounded theory: issues and discussions. Mill Valley, Calif: Sociology Press: First printing.

Glaser, B. G. (2001). The grounded theory persepctive: conceptualization contrasted with description. Calif.: Sociology Press: Mill Valley.

Glaser, B. G., and Strauss Anselm (1967). The Discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. London: Wiedenfeld and Nicholson.

de Groot, A. D. “The Meaning of ‘Significance’ for Different Types of Research [Translated and Annotated by Eric-Jan Wagenmakers, Denny Borsboom, Josine Verhagen, Rogier Kievit, & Bakker, M. (2014). Angelique Cramer, Dora Matzke, Don Mellenbergh, and Han L. J. van Der Maas].” Acta Psychologica 148:188–94. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2014.02.001.

Haven, T. L., Timothy, M., Errington, K. S., Gleditsch, L., van Grootel, A. M., Jacobs, F. G., Kern, Rafael Piñeiro, Fernando Rosenblatt, and, & Mokkink, L. B. (2020). “Preregistering Qualitative Research: A Delphi Study.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 19:160940692097641. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920976417.

Haven, T. L., & Van Grootel, D. L. (2019). Preregistering qualitative research. Accountability in Research, 26(3), 229–244. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2019.1580147.

Hendriks, F., & Kienhues, D., and Rainer Bromme (2020). Replication Crisis = Trust Crisis? The effect of successful vs failed replications on Laypeople’s Trust in Researchers and Research. Public Understanding of Science, 29(3), 270–288. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662520902383.

Ikeda, A., Xu, H., Fuji, N., & Zhu, S. (2019). and Yuki Yamada. Questionable Research Practices Following Pre-Registration. preprint. PsyArXiv. doi: https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/b8pw9.

Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2008). Why most discovered true Associations are inflated. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.), 19(5), 640–648. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e31818131e7.

Jacobs, A. (2020). “Pre-Registration and Results-Free Review in Observational and Qualitative Research.” Pp. 221–64 in The Production of Knowledge: Enhancing Progress in Social Science, edited by C. Elman, J. Gerrig, and J. Mahoney. Cambridge University Press.

James, W. (1907). Pragmatism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Hackett.

Jamieson, K. H. (2018). “Crisis or Self-Correction: Rethinking Media Narratives about the Well-Being of Science.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115(11):2620–27. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1708276114.

Janz, N., and Jeremy Freese (2021). Replicate others as you would like to be replicated yourself. PS: Political Science & Politics, 54(2), 305–308. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096520000943.

Katz, J. (2015). A theory of qualitative methodology: the Social System of Analytic Fieldwork. Méthod(e)s: African Review of Social Sciences Methodology, 1(1–2), 131–146. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/23754745.2015.1017282.

Kavanagh, C. M., & Kapitány, R. (2019). Promoting the Benefits and Clarifying Misconceptions about Preregistration, Preprints, and Open Science for Cognitive Science of Religion. preprint. PsyArXiv. doi: https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/e9zs8.

Lakens, D. (2019). The Value of Preregistration for Psychological Science: A Conceptual Analysis. preprint. PsyArXiv. doi: https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/jbh4w.

Layder, D. (1998). Sociological practice: linking theory and Social Research. London; Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage.

Locascio, J. J. (2019). The impact of results Blind Science Publishing on Statistical Consultation and collaboration. The American Statistician, 73(sup1), 346–351. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00031305.2018.1505658.

Long, J. S. (2009). The Workflow of Data Analysis Using Stata. Stata Press Books.

Lucchesi, L. R., Petra, M., Kuhnert, J. L., & Davis (2022). and Lexing Xie. “Smallset Timelines: A Visual Representation of Data Preprocessing Decisions.” Pp. 1136–53 in 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency. Seoul Republic of Korea: ACM.

Maner, J. K. (2014). Let’s put our money where our mouth is: if authors are to Change their Ways, Reviewers (and editors) must change with them. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9(3), 343–351. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614528215.

Moody, J. W., Lisa, A., Keister, & Ramos, M. C. (2022). Reproducibility in the Social Sciences. Annual Review of Sociology, 48, 21.

Nosek, B. A., Ebersole, C. R., DeHaven, A. C., & Mellor, D. T. (2018). “The Preregistration Revolution.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115(11):2600–2606. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1708274114.

Nosek, B. A., Daniël, & Lakens (2014). Registered reports: a method to increase the credibility of published results. Social Psychology, 45(3), 137–141. doi: https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000192.

Nuijten, M. B., Chris, H. J., Hartgerink, Marcel, A. L. M., van Assen, S., & Epskamp, and Jelte M. Wicherts (2016). The prevalence of statistical reporting errors in psychology (1985–2013). Behavior Research Methods, 48(4), 1205–1226. doi: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-015-0664-2.

Olken, B. A. (2015). Promises and perils of Pre-Analysis Plans. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(3), 61–80. doi: https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.29.3.61.

Parker, T., & Fraser, H., and Shinichi Nakagawa (2019). Making Conservation Science more Reliable with Preregistration and Registered Reports. Conservation Biology, 33(4), 747–750. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13342.

Petticrew, M., Egan, M., Thomson, H., Hamilton, V., Kunkler, R., & Roberts, H. (2008). “Publication Bias in Qualitative Research: What Becomes of Qualitative Research Presented at Conferences?” Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 62(6):552–54. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2006.059394.

Pham, M., & Tuan, and Travis Tae Oh (2021). Preregistration is neither sufficient nor necessary for Good Science. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 31(1), 163–176. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/jcpy.1209.

Präg, P., & Ersanilli, E., and Alexi Gugushvili (2022). An invitation to Submit. European Societies, 24(1), 1–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2022.2029131.

Resnik, D. B., & Neal Stewart, C. (2012). Misconduct versus honest error and scientific disagreement. Accountability in Research, 19(1), 56–63. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2012.650948.

Reyes, V. (2020). Ethnographic Toolkit: Strategic Positionality and Researchers’ visible and invisible tools in Field Research. Ethnography, 21(2), 220–240. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1466138118805121.

Rosenthal, R. (1979). The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychological Bulletin, 86(3), 638–641. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.86.3.638.

Rubin, M. (2017). An evaluation of four solutions to the forking Paths Problem: adjusted alpha, preregistration, sensitivity analyses, and abandoning the Neyman-Pearson Approach. Review of General Psychology, 21(4), 321–329. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000135.

Schäfer, T., and Marcus A. Schwarz (2019). The meaningfulness of Effect Sizes in Psychological Research: differences between sub-disciplines and the impact of potential biases. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 813. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00813.

Scheel, A. M. (2021). An excess of positive results: comparing the standard psychology literature with registered reports. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 4(2), 1–12.

Shamoo, A. E., & Resnick, D. B. (2015). Responsible Conduct of Research. Third edition. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

Shiffrin, R. M., & Börner, K. (2018). and Stephen M. Stigler. “Scientific Progress despite Irreproducibility: A Seeming Paradox.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115(11):2632–39. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1711786114.

Simmons, J. P., Leif, D., & Nelson, and Uri Simonsohn (2011). False-positive psychology: undisclosed flexibility in Data Collection and Analysis allows presenting anything as significant. Psychological Science, 22(11), 1359–1366. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611417632.

Simmons, J. P., & Nelson, L., and Uri Simonsohn (2021). Pre-registration: why and how. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 31(1), 151–162. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/jcpy.1208.

Simonsohn, U., Nelson, L. D., & Simmons, J. P. (2014). P-Curve: a key to the file-drawer. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143(2), 14. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033242.

Soderberg, C. K., Timothy, M., Errington, S. R., Schiavone, J., Bottesini, F. S., Thorn, S., Vazire, K. M., Esterling, & Nosek, B. A. (2021). Initial evidence of Research Quality of Registered Reports compared with the Standard Publishing Model. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(8), 990–997. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01142-4.

Szucs, D. (2016). A Tutorial on Hunting Statistical significance by chasing N. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01444.

Timmermans, S., and Iddo Tavory (2012). Theory construction in qualitative research: from grounded theory to Abductive Analysis. Sociological Theory, 30(3), 167–186.

van Elisabeth, V. A., and Roger Giner-Sorolla (2016). Pre-registration in social Psychology—A discussion and suggested Template. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 67, 2–12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2016.03.004.

Wagenmakers, E. J. (2016). and Gilles Dutilh. “Seven Selfish Reasons for Preregistration.” Retrieved December 23, 2021 (from https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/seven-selfish-reasons-for-preregistration).

Wasserfall, R. (1993). Reflexivity, Feminism and Difference. Qualitative Sociology, 16(1), 23–41. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00990072.

Wetzels, R., Matzke, D., Lee, M. D., Rouder, J. N., & Iverson, G. J., and Eric-Jan Wagenmakers (2011). Statistical evidence in experimental psychology: an empirical comparison using 855 t tests. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(3), 291–298. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611406923.

Wicherts, J. M., & Bakker, M. (2011). and Dylan Molenaar. “Willingness to Share Research Data Is Related to the Strength of the Evidence and the Quality of Reporting of Statistical Results” edited by R. E. Tractenberg. PLoS ONE 6(11):e26828. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0026828.

Wicherts, J. M., Coosje, L. S., Veldkamp, Hilde, E. M., Augusteijn, M., Bakker, Robbie, C. M., van Aert, Marcel, A. L. M., & van Assen (2016). Degrees of Freedom in Planning, running, analyzing, and reporting psychological studies: a Checklist to avoid p-Hacking. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01832.

Wingen, T., & Berkessel, J. B., and Birte Englich (2020). No replication, No Trust? How low replicability Influences Trust in psychology. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 11(4), 454–463. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550619877412.

Yamada, Y. (2018). How to Crack Pre-Registration: toward transparent and Open Science. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1831. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01831.

Young, C. (2018). Model uncertainty and the Crisis in Science. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 4, 237802311773720. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023117737206.

Zoorob, M. (2020). Do police brutality stories reduce 911 calls? Reassessing an important Criminological Finding. American Sociological Review, 85(1), 176–183. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419895254.

Acknowledgements

This paper would not be possible without the excellent feedback from my colleagues Jane Sell, Anne Groggel, Jenny Davis, and Alex Frenette. Additional thanks to Andrew Wesolek and Elaine Li for research support.

Funding

This research was not funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there are no financial or non-financial conflicts of interest.

Ethics Approval

N/A There were no subjects, human or otherwise, used in this research.

Consent to Participate

N/A.

Consent for publication

N/A.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Manago, B. Preregistration and Registered Reports in Sociology: Strengths, Weaknesses, and Other Considerations. Am Soc 54, 193–210 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12108-023-09563-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12108-023-09563-6