Abstract

Background

ETV6 gene rearrangement is the molecular hallmark of secretory carcinoma (SC), however; the nature, frequency, and clinical implications of atypical ETV6 signal patterns by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) has not yet been systematically evaluated in salivary gland neoplasms.

Methods

The clinical, histopathologic, immunohistochemical and molecular features of seven salivary SCs, including four cases with atypical ETV6 FISH patterns, were retrospectively analyzed along with a critical appraisal of the literature on unbalanced ETV6 break-apart in SCs.

Results

The patients were four males and three females (31–70 years-old). Five presented with a painless neck mass and two patients with recurrent disease had a history of a previously diagnosed acinic cell carcinoma of the buccal mucosa. Histologically, there were varied combinations of microcystic, papillary, tubular, and solid patterns. All tumors were diffusely positive for S100 and/or SOX10, while 2 cases also showed luminal DOG1 staining. Rearrangement of the ETV6 locus was confirmed in 5/7 cases, of which 3 cases showed classic break-apart signals, 1 case further demonstrated duplication of the ETV6 5`end and the other loss of one copy of ETV6. Two cases harbored ETV6 deletion without rearrangement. Two of the 4 cases with atypical ETV6 FISH patterns represented recurrent tumors, one with widespread skeletal muscle involvement, bone and lymphovascular invasion. Surgical treatment resulted in gross-total resection in all 7 cases, with a median follow up of 9.5 months post-surgery for primary (n = 3) and recurrent disease (n = 1).

Conclusion

Duplication of the distal/telomeric ETV6 probe represented the most common (26/40; 65%) variant ETV6 break-apart FISH pattern in salivary SC reported in the literature and appears indicative of an aggressive clinical course.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Secretory carcinoma (SC) of the salivary glands, previously classified as mammary analogue secretory carcinoma, is a rare and distinctive neoplasm, which typically harbors a recurrent balanced chromosomal translocation t(12;15) (p13;q25) ETV6::NTRK3 [1]. Morphologically, salivary SCs closely resemble zymogen granule poor and intercalated duct-rich acinic cell carcinomas [2], but usually express various markers of breast SC including mammaglobin, S100 protein, SOX10 and GCDFP-15 [3]. Molecular testing is the gold standard for confirmation of the diagnosis, particularly if the morphology and immunohistochemistry findings are equivocal [4]. An ETV6 rearrangement may be detected on paraffin embedded tissue by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) with a break-apart probe and has been the laboratory method most widely used in salivary SC [5]. Alternatively, the fusion transcript can be identified by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction [5], with the caveat that the ETV6 gene may fuse with genes other than NTRK3 [6], or that the ETV6::NTRK3 fusion gene may display atypical exon junctions [4], or rarely harbor alternative non-ETV6 chimeric fusions as identified by next generation sequencing [7]. Further, atypical FISH signal patterns have also been described with the ETV6 and NTRK3 break-apart probes in salivary SCs [8, 9]. The authors present a series of salivary gland malignancies with assessment for rearrangement of the ETV6 (12p13) locus using a break-apart probe and review the literature on salivary gland tumors with an atypical ETV6 FISH result.

Materials and Methods

Seven patients diagnosed with salivary SCs between 2017 and 2023, with either a typical or an atypical pattern on FISH for ETV6 rearrangement, were identified from the archives of the Departments of Oral and Anatomical Pathology, University of the Witwatersrand and National Health Laboratory Service, Johannesburg, South Africa. Patient clinical information, histopathologic reports and immunohistochemical expression profile for S100 protein and/or SOX10 and DOG1 were reviewed. FISH analysis was performed as part of the routine diagnostic work-up using the Vysis LSI Dual Colour ETV6 break-apart rearrangement probe. A normal nucleus shows two fusion signals while a case positive for rearrangement of ETV6 shows one fusion, one orange and one green signal. The orange probe spans the 5’telomeric end of the ETV6 gene from intron 2 and the green probe flanks the 3’centromeric region of the ETV6 gene. A minimum of 100 interphase nuclei were screened for each of the cases and images were captured using BioView Duet imaging system (BioView Ltd., Israel and Abbott Molecular, Des Plaines, IL, US). The cut-off value for positive ETV6 rearrangement was a minimum of 10% of all analyzed cells. Institutional ethics approval was obtained from the University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee (M221094).

Literature Review

We searched PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science to find relevant English-language articles (including reviews, meta-analyses, original papers, case reports, and case series) published between 2010 and 2023. Search terms included “salivary secretory carcinoma” and “mammary analogue secretory carcinoma”. The following information was extracted from each selected study (when available): the study’s publication year and country, the number of reported cases, patients’ demographic details, tumor location, final diagnosis, and details regarding the cytogenetic findings following FISH analysis with an ETV6 break-apart probe.

Results

Case Series

Clinical Characteristics

The age of the cohort ranged from 31 to 70 years (median of 36 years), with 4 males and 3 females. The tumor involved the parotid gland in 4 cases, the submandibular gland in 1 case, and the buccal mucosa in 2 cases, with the tumor size ranging from 2.3 to 6 cm (median of 3.0 cm). Most patients presented with a painless neck mass of variable duration (ranging from 2 months to 4 years). Two of the patients had a history of a previously diagnosed acinic cell carcinoma, in the same region of the current tumor that had been previously treated by surgical excision at 9- and 10-years respectively (Table 1).

Morphologic, Immunophenotypic, and Molecular Characteristics

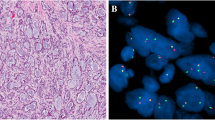

Histologically, all cases demonstrated a lobulated growth pattern with fibrous septa. The morphologic features of the tumor lobules comprised varied combinations of microcystic (cases 2, 5, 6 and 7), papillary (case 1 and 4), tubular (case 5), and follicular patterns (case 3) often with one pattern predominating (Fig. 1a-d). The microcysts contained homogenous eosinophilic secretions, positive for periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) with and without diastase digestion. In the papillary pattern, tumor cells typically filled prominent cystic spaces, thin fibrovascular cores were often visible within the papillary epithelial projections and some exhibited an overlapping microcystic pattern (Fig. 1b). Zymogen granules were absent, and the cytoplasm was eosinophilic to prominently vacuolated. The tumors were mitotically inert, and necrosis was absent. Except for one of the recurrent tumors (case 7), all SCs were cytologically low grade with bland round to ovoid nuclei, finely granular chromatin, and occasional small nucleoli. Local perineural invasion and isolated single lymph node metastases were identified in 2 cases (case 5 and 7), which included the cytologically high grade recurrent SC which further showed widespread skeletal muscle involvement (Fig. 1e), bone and lymphovascular invasion. Infiltrating nests of tumor cells and a fibrosclerotic stroma were also prominent in the latter case (Fig. 1f). Immunohistochemically, S100 staining was carried out on 6 cases (Table 1; Fig. 2. a, b), and all were diffusely positive. Cases 1–4 and case 7 demonstrated diffuse positivity for SOX10 (Fig. 2c), while case 2 and case 4 further showed luminal DOG1 staining only with no cytoplasmic reaction (Fig. 2d). The remaining 5 cases were all completely negative for DOG1. ETV6 break-apart analysis was performed in all 7 cases, and the results are summarized in Table 1; Fig. 3a-d.

Case 1 a-b: a, tumor lobules composed of anastomosing papillae within cystic spaces, magnification X10 (H&E). b, higher magnification of the papillary pattern, magnification X40 (H&E). Case 5: c, a diffuse microcystic growth pattern, magnification X10 (H&E). Case 3: d, microcysts contain dense colloid-like secretory material, magnification X40 (H&E). Case 7 e-f: e, cords of pleomorphic tumor cells with prominent eosinophilic nucleoli infiltrate skeletal muscle, magnification X200 (H&E). f, other areas in the same tumor demonstrated a sclerosing pattern, magnification X40 (H&E)

Case 1 and Case 5: a-b immunohistochemistry for S100 showed strong diffuse nuclear and cytoplasmic staining, magnification X40. Case 2 c-d: c, immunohistochemistry for SOX10 showed diffuse nuclear staining, magnification X200. d, staining for DOG1 showed moderate immunoreactivity confined to the luminal membranes of the tumor cells, magnification X200

Case 1: a FISH analysis of ETV6 gene rearrangement demonstrates a classic pattern of one fusion signal and one break-apart signal (asterisk). Case 2: b all the tumor cells analyzed have an atypical pattern of loss of one copy of ETV6 without gene rearrangement. Case 7 c-d: atypical ETV6 FISH signal pattern showing one fusion signal, separated orange and green signals (asterisk) and gain of orange signal (arrow)

Treatment and Follow-up

All 7 patients underwent surgical excision of the tumor, with one of the recurrent tumors requiring an extensive wide local excision including segmental mandibular resection, excision of the overlying skin and level II-IV neck dissection (case 7). Further treatment included subsequent total parotidectomy for close margins (< 5 mm) with elective neck dissection (case 1), and radiotherapy as an adjunct to surgery in 2 patients (case 5 and 7). Follow-up data was available in 4 cases, with a median follow up of 9.5 months post-surgery for primary (n = 3) and recurrent disease (n = 1) (Table 1).

Literature Review

The search returned 10 manuscripts published between 2012 and 2022, describing 51 salivary gland carcinomas with an atypical ETV6 FISH result (Table 2).

Discussion

In this case series report, the demographic, clinical, histopathologic and ETV6 break-apart FISH patterns of 7 salivary gland carcinomas are presented. Tumors were most frequently located in the parotid gland, followed by the buccal mucosa and submandibular gland. Four carcinomas harbored atypical ETV6 FISH patterns, of which 3 were found in non-parotid locations, and 2 cases presented as recurrent disease. To our knowledge, this is the first case series of salivary gland carcinomas with ETV6 molecular analysis in Africa, and wherein variations in ETV6 break-apart FISH patterns are compared to previous reports.

The association of atypical ETV6 FISH signals with epidemiological, clinical and prognostic parameters in salivary gland carcinomas has not been fully characterized. In a review of the literature, 36 cases of salivary SC showing an atypical ETV6 FISH pattern were identified (Table 2). Nine cases were from Western countries [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18] and 27 cases were from China [8]. There was a male predilection, and the parotid gland was the most common site of involvement. The most frequent atypical FISH pattern was ETV6 rearrangement with gain of red/orange signals (69.4%, 25/36; Table 2). Three cases exhibited changes in ETV6 copy number either in isolation [15, 18] or in combination with classic ETV6 break-apart FISH patterns [14]. Less frequently encountered ETV6 molecular aberrations in salivary SC included an ETV6 3` interstitial deletion [8, 16] and inversion of the ETV6 gene [18]. Among salivary gland tumors, although ETV6 rearrangements have been exclusively associated with SC [5], alterations in ETV6 copy number have been reported in other malignant salivary gland neoplasms (Table 2). In a comparative study assessing ETV6 gene status in salivary gland tumors, almost all cases of high-grade salivary duct carcinomas (11/12, 91.7%) demonstrated increased ETV6 fusion signals, indicative of gain of the ETV6 gene [14]. By contrast, deletion of one copy of the ETV6 gene has been observed in isolated cases of acinic cell carcinoma [10, 13, 14]. Since most of the salivary gland carcinomas with atypical ETV6 FISH patterns were identified when screening for SC among its mimics in surgical pathology archives, there is limited individual patient information currently available for evaluation of the clinical implications of alterations in ETV6 copy number in these tumors.

By contrast, there has been a greater focus on the prognostic value of the more prevalent atypical pattern of ETV6 break-apart with gain of red/orange signals in SC. Although the exact significance of this phenomenon in salivary SC is not known, the literature findings provide some insight into the clinicopathologic trends associated with this aberrant ETV6 FISH pattern. Sun et al. [8] found a higher proportion of salivary SC cases with increase of the red signal associated with necrosis, neural invasion and a higher proliferation index compared to SCs with the classic ETV6 FISH pattern. In an analysis of the clinical behavior of SC of the major salivary glands, Ayre et al. [17] reported a recurrent SC that was found to have facial nerve invasion, extraglandular extension, and a positive lymph node. Although mitotic figures were infrequent, and there was no evidence of necrosis or high-grade transformation, this case demonstrated extra red signals on ETV6 FISH analysis. The patient experienced multiple subsequent recurrences in the parotid bed and the surrounding skin of the ear and neck, and ultimately died of lung metastases and uncontrolled regional disease. A pattern of lymph node spread, perineural infiltration, vascular, skin, skeletal muscle and bone invasion was also seen in case 7 which harbored ETV6 rearrangement with gain of orange signals as described above. There are reports of similar observations in SCs presenting outside the salivary glands. An unbalanced ETV6 translocation was recently reported in 2 cases of SC presenting in the sinonasal region and where high-grade transformation was documented in one of the cases and focal geographic necrosis in the other [19]. Furthermore, in the first reported case of thyroid SC with diffuse metastatic disease at presentation, it is noteworthy that while 22% of the tumor cells had a typical ETV6 rearrangement, the remaining tumor cells showed one intact gene and one rearranged gene with gain of the red signal [20]. This case also showed prominent necrosis, multiple foci of extrathyroidal extension, an aggressive clinical course and death of the patient from extreme airway compromise [20].

In a series of secretory breast carcinoma with the ETV6::NTRK3 fusion (confirmed on RT-PCR), the morphologic features of the SCs carrying a balanced ETV6 reciprocal translocation (8/10) were typically low grade. However, 2 cases showed unbalanced ETV6 break-apart with gain of the oncogenic derivative (red signal) and with corresponding high histologic grade (moderate to marked nuclear atypia, vascular invasion and tumor necrosis) [21]. Lastly, in a single report of a primary pulmonary SC, FISH testing for ETV6 rearrangement demonstrated a clonal variant with an extra 5′ ETV6 signal pattern (83% of tumor cells). This case also demonstrated aggressive features; notably an increased mitotic count (6/10 high-power fields) but without high grade cytology, and advanced-stage disease as evidenced by lymph node metastases, visceral and pleural invasion [22]. Although the numbers of published cases thus far are low, it appears that unbalanced ETV6 break-apart with an extra 5’ETV6 signal pattern may be associated with more infiltrative histologic features and less favourable clinical outcomes in SC.

Two of the cases in the current series exhibited loss of one ETV6 fusion signal without rearrangement (Table 1). One of the cases represented a recurrent tumor in the buccal mucosa that was originally diagnosed as an acinic cell carcinoma. By immunohistochemistry, the tumor cells showed diffuse S100 and SOX10 positivity, while luminal DOG1 staining without a cytoplasmic reaction was also observed in this case. Interestingly, Stevens et al. [14] reported a similar pattern of apical membranous DOG1 staining in 10/12 SCs and wherein typical ETV6 rearrangements were documented in 10/11 cases tested. This DOG1 staining pattern contrasted with the diffuse, strong, cytoplasmic and canalicular DOG1 expression that was demonstrated in acinic cell carcinomas in the same study. In another study, DOG1 expression was noted along the luminal surface of tumor cells in one-third of salivary SCs with atypical FISH signal patterns using break-apart and ETV6::NTRK3 fusion probes [8]. Given the expanding molecular profile of SC these cases appear to represent a subset of salivary SC with divergent molecular findings.

In this cohort, whilst the overall histomorphologic and immunohistochemical findings of those cases without typical 1F1O1G ETV6 rearrangements were considered consistent with SC, orthogonal testing for an ETV6::NTRK3 fusion gene or other associated gene fusion was not available to confirm the diagnosis. The possibility of an intercalated duct type intraductal carcinoma was, however, considered unlikely as a rim of myoepithelial cells surrounding the tumor lobules was not visualized by p63 immunostaining in these cases. Nevertheless, given the limitations of this study which includes the lack of testing for NR4A3 (NOR1) or NR4A2 (NURR1) expression, a non-secretory salivary carcinoma cannot be entirely excluded in those cases without typical 1F1O1G rearrangements. The nosology of salivary gland tumors harboring deletion of one ETV6 fusion signal and demonstrating apical membranous staining for DOG1 around tumor lumina thus remains to be clarified. Future investigations are also needed to determine whether the nature and frequency of ETV6 genetic abnormalities in salivary SC varies by geographic region or are instead acquired in association with disease progression.

Conclusion

Among the 40 cases of salivary SC showing variations in ETV6 break-apart FISH patterns as reported in the literature and including 4 cases from the current series, ETV6 rearrangement with duplication of the ETV6 5`end (1F1GnR, n ≥ 2) represented the most common (26/40; 65%) variation. Larger studies are required to confirm the link of duplication of the distal/telomeric ETV6 probe with a more aggressive disease course in salivary SC.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Skálová A, Vanecek T, Sima R, Laco J, Weinreb I, Perez-Ordonez B et al (2010) Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands, containing the ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene: a hitherto undescribed salivary gland tumor entity. Am J Surg Pathol 34:599–608

Parekh V, Stevens TM (2016) Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med 140:997–1001

Projetti F, Lacroix-Triki M, Serrano E, Vergez S, Barres BH, Meilleroux J et al (2015) A comparative immunohistochemistry study of diagnostic tools in salivary gland tumors: usefulness of mammaglobin, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, and p63 cytoplasmic staining for the diagnosis of mammary analog secretory carcinoma? J Oral Pathol Med 44:244–251

Skálová A, Vanecek T, Simpson RH, Laco J, Majewska H, Baneckova M et al (2016) Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands: Molecular Analysis of 25 ETV6 gene rearranged tumors with lack of detection of classical ETV6-NTRK3 Fusion transcript by standard RT-PCR: report of 4 cases harboring ETV6-X Gene Fusion. Am J Surg Pathol 40:3–13

Inaki R, Abe M, Zong L, Abe T, Shinozaki-Ushiku A, Ushiku T et al (2017) Secretory carcinoma - impact of translocation and gene fusions on salivary gland tumor. Chin J Cancer Res 29:379–384

Skálová A, Vanecek T, Martinek P, Weinreb I, Stevens TM, Simpson RHW et al (2018) Molecular Profiling of Mammary Analog Secretory Carcinoma revealed a subset of tumors harboring a Novel ETV6-RET translocation: report of 10 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 42:234–246

Skálová A, Banečkova M, Thompson LDR, Ptáková N, Stevens TM, Brcic L et al (2020) Expanding the Molecular Spectrum of Secretory Carcinoma of salivary glands with a Novel VIM-RET Fusion. Am J Surg Pathol 44:1295–1307

Sun J, Li J, Tian Z, Zhang C, Xia R, He Y (2022) Atypical/unbalanced ETV6/NTRK3 rearrangement in salivary secretory carcinoma with a focus on the incidence, the patterns, and the clinical implications. J Oral Pathol Med 51:721–729

Wagner F, Greim R, Krebs K, Luebben F, Dimmler A (2021) Characterization of an ETV6-NTRK3 rearrangement with unusual, but highly significant FISH signal pattern in a secretory carcinoma of the salivary gland: a case report. Diagn Pathol 16:73

Chiosea SI, Griffith C, Assaad A, Seethala RR (2012) The profile of acinic cell carcinoma after recognition of mammary analog secretory carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 36:343–350

Williams L, Chiosea SI (2013) Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma mimicking salivary adenoma. Head Neck Pathol 7:316–319

Patel KR, Solomon IH, El-Mofty SK, Lewis JS Jr., Chernock RD (2013) Mammaglobin and S-100 immunoreactivity in salivary gland carcinomas other than mammary analogue secretory carcinoma. Hum Pathol 44:2501–2508

Pinto A, Nosé V, Rojas C, Fan YS, Gomez-Fernandez C (2014) Searching for mammary analogue [corrected] secretory carcinoma of salivary gland among its mimics. Mod Pathol 27:30–37

Stevens TM, Kovalovsky AO, Velosa C, Shi Q, Dai Q, Owen RP et al (2015) Mammary analog secretory carcinoma, low-grade salivary duct carcinoma, and mimickers: a comparative study. Mod Pathol 28:1084–1100

Khurram SA, Sultan-Khan J, Atkey N, Speight PM (2016) Cytogenetic and immunohistochemical characterization of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 122:731–742

Naous R, Zhang S, Valente A, Stemmer M, Khurana KK (2017) Utility of immunohistochemistry and ETV6 (12p13) gene rearrangement in identifying secretory carcinoma of salivary gland among previously diagnosed cases of Acinic Cell Carcinoma. Patholog Res Int 2017:1497023

Ayre G, Hyrcza M, Wu J, Berthelet E, Skálová A, Thomson T (2019) Secretory carcinoma of the major salivary gland: Provincial population-based analysis of clinical behavior and outcomes. Head Neck 41:1227–1236

Xu B, Viswanathan K, Umrau K, Al-Ameri TAD, Dogan S, Magliocca K et al (2022) Secretory carcinoma of the salivary gland: a multi-institutional clinicopathologic study of 90 cases with emphasis on grading and prognostic factors. Histopathology 81:670–679

Yue C, Zhao X, Ma D, Piao Y (2022) Secretory carcinoma of the sinonasal cavity and pharynx: a retrospective analysis of four cases and literature review. Ann Diagn Pathol 61:152052

Desai MA, Mehrad M, Ely KA, Bishop JA, Netterville J, Aulino JM et al (2019) Secretory carcinoma of the thyroid gland: report of a highly aggressive case clinically mimicking undifferentiated carcinoma and review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol 13:562–572

Del Castillo M, Chibon F, Arnould L, Croce S, Ribeiro A, Perot G et al (2015) Secretory breast carcinoma: a histopathologic and genomic Spectrum characterized by a joint specific ETV6-NTRK3 Gene Fusion. Am J Surg Pathol 39:1458–1467

Huang T, McHugh JB, Berry GJ, Myers JL (2018) Primary mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of the lung: a case report. Hum Pathol 74:109–113

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of the Witwatersrand. No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Open access funding provided by University of the Witwatersrand.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by FM, SB and ZM. The first draft of the manuscript was written by FM. The initial review and editing were performed by KH, ZM and SN. The final review and editing by SB and KH. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

This case series report has obtained institutional approval from the University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee (M221094).

Consent to Participate

For this type of study informed consent is not required.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahomed, F., de Bruin, J., Ngwenya, S. et al. ETV6 Molecular Heterogeneity in Salivary Secretory Carcinoma: A Case Series Report and Literature Review. Head and Neck Pathol 18, 66 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-024-01673-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-024-01673-y