Abstract

Objective

To know the risk of endometrial cancer (EC) in a population of women with BRCA 1/2 pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants after risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO).

Methods

The study cohort included data from 857 women with BRCA mutations who underwent RRSO visited four hospitals in Catalonia, Spain, from January 1, 1999 to April 30, 2019. Standardized incidence ratio (SIR) of EC was calculated in these patients using data from a regional population-based cancer registry.

Results

After RRSO, eight cases of EC were identified. Four in BRCA 1 carriers and four in BRCA2 carriers. The expected number of cases of EC was 3.67 cases, with a SIR of 2.18 and a 95% CI (0.93–3.95).

Conclusions

In our cohort, the risk of EC in BRCA1/2 carriers after RRSO is not greater than expected. Hysterectomy is not routinely recommended for these patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Women who are germline BRCA 1/2 mutation carriers are at an increased risk of developing tumours, specially breast and ovarian/fallopian tube cancers, as compared with the general population. It is well-studied that these patients have a lifetime risk of ovarian cancer of 39–46% if they carry the BRCA1 mutation and 12–20% if they carry the BRCA2 mutation [1].

The estimated prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations is dependent on the population and can vary between 1 in 300 and 1 in 800, respectively, being higher in populations such as Ashkenazi Jewish [1, 2].

Nowadays, genetic testing for BRCA is recommended in women diagnosed with ovarian cancer regardless of their family history as they might benefit from PARP inhibitor therapies. This fact can increase the detection of BRCA carriers which can, therefore, lead to changes in treatment decisions regarding prophylactic surgeries.

Current guidelines recommend undergoing risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) by the age of 35–40 for BRCA1 and by the age of 40–45 for BRCA2 and once child-bearing is complete to reduce the risk of ovarian or fallopian tube cancer by 80–90% and also to reduce mortality in patients harbouring these mutations [2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. However, hysterectomy at the same time as RRSO is controversial.

Such information remains of clinical importance since endometrial cancer is the most common gynaecological malignancy, yet it is still unknown if there is any increased risk in women with BRCA mutations. Moreover, it must be considered that endometrial cancer in early stages has a good prognosis while survival in locally advanced or metastatic setting is nowadays very limited, with a 5 years survival rate of approximately 47% [9]. In addition, its prognosis may change with the prophylactic surgery if added benefit of hysterectomy had been confirmed. Furthermore, if the association of an increased EC risk in BRCA carriers had been confirmed, it might influence clinical implications such as genetic counselling and treatment strategies.

Regarding this topic, different articles have been published with discordant results. Few authors have recommended concomitant hysterectomy because there might be a high risk of EC among patients carrying a BRCA mutation. Moreover, a study [10] has suggested an association between BRCA1 and serous endometrial cancer subtype. Nevertheless, outcomes of other studies have not confirmed this [11,12,13,14].

In addition, there have also been different findings related to the EC cancer risk possibly confounded by the use of tamoxifen, an adjuvant therapy for hormone receptor-positive breast cancer [15,16,17,18].

The goal of our analysis was to estimate the incidence of endometrial cancer among a cohort of women with BRCA mutations who underwent risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy compared to general population to assess the benefit of undergoing hysterectomy in the RRSO setting.

Material and methods

Study cohort

Data from 2,237 women with BRCA mutation, 857 of which underwent RRSO without a prior hysterectomy, visited four hospitals in Catalonia (Spain) from January 1, 1999 to April 30, 2019 were analyzed. Data were obtained from the Hereditary Cancer Registry that contains data ambispectively collected. Participants were followed-up until January 1, 2023 for a median of 7.13 (IQR 6.31) years after BRCA testing. Censoring occurred at either endometrial cancer diagnosis, last follow-up or death.

The cohort inclusion criteria were (a) positive BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation test results, (b) aged 18 or older (c) no previous history of endometrial cancer and (d) risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy.

Information related to age, EC histology and stage, previous history of breast cancer (BC), treatment with tamoxifen and its duration, dates of EC diagnoses and type of surgery were collected from each patient through a review based on medical histories, surgical and pathology reports.

All patients have signed a written consent which has been approved by the local Ethical Committee and conducted in accordance with the guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysis

To compare the risks with the general population, the standardized incidence ratios were calculated by dividing the number of observed endometrial cancer cases by the number of expected ones. The number of expected cases was calculated taking into account the incidence rate standardized by age of EC of the general population in Catalonia, from 2008 to 2018 that was 21.5 new cases per 100,000 women/year. Data were obtained from the Population-based Cancer Registry database.

Results

A total of 2,237 BRCA1/2+ patients were selected. Among them 1,122 (49.36%) were BRCA1 mutated and 1,115 (49.84%) BRCA2. Eight hundred fifty-seven 857 (37%) underwent RRSO without hysterectomy (423 (49.35%) were BRCA1 and 434 (50.64%) BRCA2) and were included in the analyses.

After RRSO, eight cases (0.93%) of EC were identified. Four of them in BRCA1 and four in BRCA2. The characteristics of these EC were as follows (Table 1): four were endometrioid, three were serous and one was a carcinosarcoma. Two of the three serous subtypes were in patients BRCA1 mutated. Six were stage IA according to the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) classification, one was stage IIIA and one IIIC1. The median age was 52 years old (range 45–70). Between the date of RRSO and EC diagnosis, 1–3 years had passed in three cases and 3–6 years in four patients whereas 13 years was the time passed in one case.

Six out of eight patients had a history of breast cancer, and of these, three had taken tamoxifen previously (one case for 5 years and the others for 2 years). Of those who had taken TMX, the interval between breast cancer diagnosis and endometrial cancer was 3.9–19 years. One of these had serous histology and BRCA1 mutation, and the other two had endometrioid and serous histology with a BRCA2 mutation.

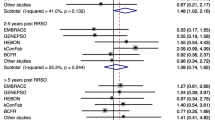

In our analyses, expected EC in the cohort studied would be 3.67 cases, being our overall SIR 2.18 with a 95% CI (0.93–3.95). Expected cases separately for BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers were 1.82 and 1.87, respectively, being the standardized incidence rates 2.2 (95% CI 0.57–4.88) and 2.14 (95% CI 0.49–4.15) respectively, resulting in an incidence rate ratio for BRCA2–BRCA1 of 0.97 (95% CI 0.23–4.01).

Discussion

BRCA mutation and endometrial cancer

Several articles have been published evaluating the impact of RRSO on BRCA-associated cancer risk [2, 3, 5, 19] due to the importance of reducing ovarian, fallopian tube, peritoneal and breast cancers established in these patients as well as increasing survival.

At the time of risk-reducing surgery, both ovaries and fallopian tubes are removed, but there is controversy as to whether a hysterectomy should be performed concomitantly owing to a possible strong association between endometrial cancer and BRCA mutations which remains to be demonstrated.

The contribution of BRCA mutations to endometrial cancer has been reported in some publications, such as that of Kauff et al. [3] who reported the risk of EC arose from the small amount of intramural fallopian-tube tissue that is remains after the salpingo-oophorectomy. Furthermore, a published article by Shu et. al [10] suggested an increased risk of serous endometrial cancer in BRCA1 mutation carriers (O:E ratio 22.2; 95% CI, 6.1–56.9; p < 0.001). Similar results were shown in recent studies where BRCA 1 and 2 carriers have an increased risk of serous endometrial carcinoma and prophylactic hysterectomy could be discussed for this population [6, 22, 23]. A study published by De Jonge et al. demonstrated an increased risk of EC in patients with germline BRCA-associated hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome. Those patients with loss-of-heterozygosity were more likely to be diagnosed with non-endometrioid and histological grade 3 endometrial cancer [20]. In 2021, a paper of a Dutch nationwide cohort study described a two-to-threefold increased risk for EC in BRCA 1/2 mutation carriers, especially for rare histological subgroups such as serous-like and p-53 abnormal EC [21].

Nevertheless, a recent systematic review has identified all relevant studies regarding BRCA mutation and EC. Only 5 out of 14 studies have found a correlation between BRCA mutation and an increased risk of EC [23]. Hence, this does not provide evidence in favour of performing a routine hysterectomy at the time of RRSO.

In line with these findings, our results indicate there is no evidence that carrying the BRCA1 mutation gives a higher likelihood for developing EC than carrying the BRCA2 mutation (0.97 95% CI 0.23–4.01).

Tamoxifen and endometrial cancer

Tamoxifen is a selective oestrogen receptor modulator. It has an anti-oestrogenic effect on breast tissue while it acts as an oestrogenic factor in endometrium. It has been widely used as adjuvant treatment for breast cancer.

It is important to take into account the role of tamoxifen as it is a known risk for endometrial cancer [15, 16] specifically in postmenopausal patients [18]. Multiple studies have shown an increased risk of endometrial cancer in association with prolonged tamoxifen use. Some authors published an increased risk of aggressive histology of endometrial cancer with poor prognosis in those treated with tamoxifen [18, 25] while others have not found this relationship [14, 24].

Segev et al. [16] found that BRCA1 mutation carriers with a history of tamoxifen use had a significant increase in the incidence of endometrial cancer (O:E ratio 4.43; 95% CI, 1.94–8.76). Additionally, Wen et al. [25] reported that those women with decreased BRCA1 protein expression treated with tamoxifen might be more susceptible to serous endometrial cancer. Whereas some studies have not confirmed this information [12], there are authors who support that hysterectomy should be suggested only to those likely to use tamoxifen [16] and taking into account that this surgical procedure has no negligible risks [26].

In our cohort, three out of eight EC patients had been treated with tamoxifen due to a previous diagnosis of breast cancer, indicating that it could be one of the risk factors that contributed to the development of EC. One of them was BRCA1 and two BRCA2 mutation carriers. However, none of them were postmenopausal, as expected based on previous studies.

Hysterectomy and endometrial cancer

Despite being less with minimally invasive procedure, risks and benefits of prophylactic hysterectomy should be weighed and discussed with patients to address issues of quality of life and morbi-mortality of this intervention [4]. It is known that performing concomitant surgeries increases morbidity and complications such as pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence, and it may result in sexual dysfunction. However, advantages of concomitant hysterectomy at the time of RRSO should be balanced regarding management of menopausal symptoms with hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Combined HRT with oestrogen and progestin are required when the uterus is left in place because unopposed oestrogen increases EC risk, but combined HRT may further increase the risk of BC which is important to BRCA carriers [23].

Based on the results of Shu et al., Havrilesky and colleagues [26] estimated the mortality reduction benefit and cost-effectiveness of performing a hysterectomy at the time of RRSO to prevent serous uterine cancer in BRCA1 carriers in the United States. They suggested that hysterectomy is highly cost-effective with an increased life expectancy of 5 months.

Furthermore, three population-based studies reported mortality due to hysterectomy of 0.03–0.06% which is much lower compared to the estimate risk for serous uterine cancer in patients aged up to 70 years old of 2.6% in BRCA1 carriers [10].

The strengths of our study are the high number of patients from a multicentre ambispective cohort that include clinical data collected from medical and pathology reports. However, we recognize a few limitations such as data on risk factors (epidemiological, hormone replacement therapy or lifestyle) associated with EC that does not allow for drawing conclusions.

Conclusions

This study revealed that there was no significantly higher risk of endometrial cancer in BRCA-mutation carriers, and despite some literature suggesting an association between BRCA1 and serous endometrial cancer, this study does not reinforce this association. Further large studies are required to better estimate the risk of EC before hysterectomy at the time of RRSO and whether it is justifiable for women harbouring BRCA mutations. A multidisciplinary approach should be offered to these patients to assess the best risk-reducing options.

References

Nair N, Schwarts M, Guzzardi L, Durlester N, Pan S, Overbey J, et al. Hysterectomy at the time of risk-reducing surgery in BRCA carriers. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2018;26(October):71–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gore.2018.10.003.

Domchek SM, Freibel TM, Singer C, Evans G, Lynch H, Isaacs C, et al. Association of risk-reducing surgery in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers with cancer risk and mortality. J Am Med Assoc. 2010;304(9):967–75. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.1237.Association.

Kauff ND, Satagopan JM, Robson ME, Scheuer L, Hensley M, Hudis CA, et al. Risk-reducing Salpingo–Oophorectomy in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2002;57(9):574–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006254-200209000-00016.

Paluch-Shimon S, Cardoso F, Sessa C, Balmana J, Cardoso MJ, Gilbert F, et al. Prevention and screening in BRCA mutation carriers and other breast/ovarian hereditary cancer syndromes: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for cancer prevention and screening. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(Supplement 5):v103–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdw327.

Finch APM, Lubinski J, Moller P, Singer CF, Karlan B, Senter L, et al. Impact of oophorectomy on cancer incidence and mortality in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15):1547–53. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.53.2820.

Saule C, Mouret-Fourme E, Biraux A, Becette V, Rouzier R, Houdayer C, et al. Risk of serous endometrial carcinoma in women with pathogenic BRCA1/2 variant after risk-reducing Salpingo–Oophorectomy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(2):213–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djx159.

Lavie O, Ben-Arie A, Faro J, Barak F, Haya N, Auslender R, et al. Brca germline mutations in women with uterine serous carcinoma-still a debate. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20(9):477. https://doi.org/10.1111/IGC.0B013E3181CD242F.

Daly M, Pal T, Alhilli Z, Arun B, Buys SS, Cheng H, et al., “NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: breast, ovarian, and pancreatic”. https://www.nccn.org/home/member-. Accessed: 03 Apr 2023

Halassy S, Au K, Malviya V, Mullings-Britton J. Prophylactic bilateral Salpingo–oophorectomy and eventual development of endometrial cancer: two individual case reports. Case Rep Womens Health. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CRWH.2020.E00195.

Shu CA, Pike MC, Jotwani AR, Friebel TM, Soslow RA, Levine DA, et al. Uterine cancer after risk-reducing salpingo–oophorectomy without hysterectomy in women with BRCA mutations. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(11):1434. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMAONCOL.2016.1820.

Kitson SJ, Bafligil C, Ryan NAJ, Lallo F, Woodward ER, Clayton RD, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variant carriers and endometrial cancer risk: a cohort study. Eur J Cancer. 2020;136:169–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2020.05.030.

Reitsma W, Mourits MJE, De Bock GH, Hollema H. Endometrium is not the primary site of origin of pelvic high-grade serous carcinoma in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers. Mod Pathol. 2013;26(4):572–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2012.169.

Lee YC, Milne RL, Lhereux S, Friedlander M, McLachlan SA, Martin KL, et al. Risk of uterine cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Eur J Cancer. 2017;84:114–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2017.07.004.

Levine DA, Lin O, Barakat RR, Robson ME, McDermott D, Cohen L, et al. Risk of endometrial carcinoma associated with BRCA Mutation. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;80(3):395–8. https://doi.org/10.1006/GYNO.2000.6082.

Beiner ME, Finch A, Rosen B, Lubinski J, Moller P, Ghadirian P, et al. The risk of endometrial cancer in women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. A prospective study. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;104(1):7–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.08.004.

Segev Y, Iqbal J, Lubinski J, Gronwald J, Lynch HT, Moller P, et al. The incidence of endometrial cancer in women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations: an international prospective cohort study. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;130(1):127–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.03.027.

Cuzick J, Sestak I, Bonanni B, Costantino JP, Cummings S, DeCensi A, et al. Selective oestrogen receptor modulators in prevention of breast cancer: an updated meta-analysis of individual participant data. The Lancet. 2013;381(9880):1827–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60140-3.

Bland AE, Clingaert B, Alvarez A, Lee PS, Valea FA, Berchuck A, et al. Relationship between tamoxifen use and high risk endometrial cancer histologic types. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112(1):150–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.08.035.

Rutter JL, Wacholder S, Chetrit A, Lubin F, Menczer J, Ebbers S, et al., “Gynecologic surgeries and risk of ovarian cancer in women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 ashkenazi founder mutations: an israeli population-based case-control study.” https://academic.oup.com/jnci/article/95/14/1072/2520333. Accessed: 09 Nov 2022

de Jonge MM, Mooyaart AL, Vreeswijk MPG, de Kroon CD, Van Wezel T, van Asperen CJ, et al. Linking uterine serous carcinoma to BRCA1/2-associated cancer syndrome: a meta-analysis and case report. Eur J Cancer. 2017;72:215–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2016.11.028.

De Jonge MM, De Kroon C, Jenner DJ, Oosting J, de Hullu JA, Mourits MJE, et al. Endometrial cancer risk in women with germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations: Multicenter cohort study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(9):1203–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djab036.

de Jonge MM, Ritterhouse LL, De Kroon CD, Vreeswijk MPG, Segal JP, Puranik R, et al. Germline BRCA-associated endometrial carcinoma is a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(24):7517–26. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0848.

Gasparri ML, Bellaminutti S, Farooqi AA, Cuccu I, Di Donato V, Papadia A. Endometrial cancer and BRCA mutations: a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11113114.

Barretina-Ginesta M, Galceran J, Pla H, Meléndez C, Carbó A, Izquierdo A, et al. Gynaecological malignancies after breast cancer diagnosis: a population-based study. Clin J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;2(2):113–8. https://doi.org/10.29328/journal.cjog.1001031.

Wen J, Li R, Lu Y, Shupnik MA. Decreased BRCA1 confers tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer cells by altering estrogen receptor-coregulator interactions. Oncogene. 2009;28(4):575–586

Havrilesky LJ, Moss HA, Chino J, Myers ER, Kauff ND. Mortality reduction and cost-effectiveness of performing hysterectomy at the time of risk-reducing salpingo–oophorectomy for prophylaxis against serous/serous-like uterine cancers in BRCA1 mutation carriers. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;145(3):549–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.03.025.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. This research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Manuscript: Risk of endometrial cancer after RRSO in BRCA 1/2 carriers: a multicentre cohort study. HPJ: Conceived and designed the analysis, Collected the data, Contributed data or analysis tools, Wrote the paper. MP: Collected the data, Contributed data or analysis tools, Performed the analysis, Wrote the paper. ÁJI: Contributed data or analysis tools, Performed the analysis. ED: Collected the data. AC: Collected the data. EM: Collected the data. STE: Collected the data. JB: Collected the data, Wrote the paper. CL: Collected the data. JMB: Conceived and designed the analysis, Contributed data or analysis tools, Wrote the paper. MPBG: Conceived and designed the analysis, Collected the data, Contributed data or analysis tools, Wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pla-Juher, H., Pardo, M., Izquierdo, À.J. et al. Risk of endometrial cancer after RRSO in BRCA 1/2 carriers: a multicentre cohort study. Clin Transl Oncol 26, 1033–1037 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-023-03312-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-023-03312-4