Abstract

In the Netherlands the share of immigrants in the total population has steadily increased during recent decades. The present paper takes a look at wage differences between natives and migrants who are equally educated. This reduces potential skills biases in our analysis of wages. We apply a Mincer equation in estimating the wage differences between natives and migrants. We analyse only young graduates; the conventional human capital factor cannot explain the differences in monthly gross wages. Therefore, we have to look further into “otherness” factors, such as parents’ roots, to find an alternative explanation. Our empirical results show that acquiring Dutch human capital, such as Dutch-specific skills, language, and even integration in the long-term for first-generation migrants, and for a group of second-generation migrants with a non-OECD background, do not overcome wage differences in the Dutch labor market. Furthermore, age structure also plays a role in the payment of different wages in the labor market due to an age discrimination effect: immigrants who invest in their education at later age earn lower wages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The share of foreign-born population has steadily increased in recent years in most developed countries. This has prompted much research on the social and economic impacts of immigrants on the host society. Such impacts may refer to job creation (or loss), wage changes, welfare and growth effects, trade and tourism flows, or new business formation. A broad review of migration impact assessment methods can found in Nijkamp et al. (2012). An important and recurrent question is whether a migration inflow may widen the wage differences between natives and migrants. The present paper will examine in particular the wage gap between natives and migrants with a higher education diploma in the Netherlands.

In the Netherlands, the share of immigrants in the total population has risen substantially in recent decades. Figure 1 below describes the immigration development over the past 10 years. As can be seen, the share of younger immigrants is higher compared to the older categories. This indicates that migrants who migrated to the Netherlands during that period were mostly young people. Especially, the 20–30 age group is large, and their share increases as we move toward 2010. Some of these migrants have completed their education in their country of origin; others in the Netherlands.Footnote 1 With reference to Eurostat (2010), there were 1.8 million foreign-born residents in the Netherlands, corresponding to 11.1 % of the total population. Of these, 1.4 million (8.5 %) were born outside the EU and 0.428 million (2.6 %) were born in another EU Member State.

Immigration and the immigrants’ economic impact on the host society have long been a sensitive political topic in many developed countries. As migrants are heterogeneous in terms of skills and social demographic characteristics, their impact on the host country labor market can also be different. There is much evidence of a wage gap between migrant workers and native workers (Bovenkerk et al. 1995), but the reasons need a careful study.

The aim of the present paper is, first, to examine the gross salary of students who have graduated from a Dutch higher professional education, and then to make a comparison between migrants and natives in the labor market. In doing so, we employ the Mincer equation and apply it to graduates of Dutch higher professional education. Clearly, the present paper contributes to the rapidly emerging set of studies on wage differences between migrants and natives in the following ways. First, in our analysis the role of skill bias will be limited: natives and migrants in our sample have largely obtained the same degrees from a higher education institution. Secondly, we also control for ‘otherness’ which relates to the ethnic background of migrants; our empirical results reveal that wage discrimination is related to the individuals’ geographic roots. Graduates from non-OECD countries are receiving relatively low wages, if compared with native and OECD graduates. Furthermore, a part of the effect can be assigned to an age discrimination effect in the labor market: immigrants who invest in their education at later age earn lower wages. Therefore, age structure plays a role in the payment of different wages in the labor market.

The paper has the following structure. After reviewing the literature on wage differences between immigrants and natives, the paper presents some empirical results, by using data from Maastricht UniversityFootnote 2 for the years 2007–2010 on graduates of higher professional education. We found that there is no wage difference between natives and second-generation migrants, but the wage gap between first-generation migrants and natives is −3 %. Furthermore, we also find that migrants coming from outside the OECD region receive a lower gross salary in comparison with OECD area migrants. This study demonstrates that the most important factor in the wage gap between immigrants and natives does not strongly correlate with their human capital endowment, but probably more with the effect of “otherness”.

The remaining part of the paper is now organized as follows. Section 2 provides a concise literature review. Section 3 describes our data set and offers a descriptive analysis. Next, Sect. 4 presents the empirical results, and Sect. 5 concludes.

2 Literature review

In recent years, special attention has been devoted to the impact of immigrants in general and highly educated and skilled immigrants, in particular. These studies tend to differ from an analytical perspective; some studies look at the effect of immigrants on wages of natives (Borjas 2003; Borjas and Katz 2007; Ottaviano and Peri 2012; Foged and Peri 2015), while other studies observe this phenomenon from a wage discrimination perspective (Groot 2013; Friedberg 2000). Although developed countries are often in desperate need of skilled and highly educated immigrants, immigrants and even the children of immigrants (also called the second-generation) are in various cases nit enjoying equal job opportunities and wages.

According to human capital theory, the difference in labor market outcomes is related to an individual’s investment in education and job training (Becker and Becker 1998; Mincer 1974). Education and job training increase an individual’s productivity, which in turn has a positive impact on a person’s earning. On the basis of this theory, individuals with the same labor supply characteristics are expected to have the same wage and employment opportunity. Furthermore, as the conventional human capital model cannot fully explain the differences in terms of wage and employment opportunities between migrants and natives, some additional adjustments have been added to the standard model, for example, whether an individuals’ investment in human capital was accumulated in the country of origin or country of destination. The same holds true for the years of work experience, especially if they are from non-OECD countries (Coulon de 2001; Friedberg 2000), lack of host country’s specific skills, language and knowledge. In due time, however, after immigrants have lived for a number of years in the host country, they steadily acquire the host country’s specific knowledge and language. Consequently, their labor market performance will likely increase, and in the course of time their wage difference in comparison to natives will be diminished (Friedberg 2000; Borjas 1985; Chiswick 1978). In our study we focus on immigrants who have graduated from Dutch higher education institutions; therefore, they have the same educational qualifications as the natives. If these were the only relevant distinct factors, there would not be a wage difference between immigrants and natives, and certainly not between second-generation immigrants and natives.

At the same time, the concept of social capital indicates that social ties produce transferable values, and can lead people toward better employment opportunities and possibly higher paid jobs. According to Bourdieu and Wacuant (1992, p 119) “social capital is the sum of the resources that accrue to an individual or a group by virtue of possessing a durable network of more or less institutional relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition.” This brings two important elements of social capital: (1) the strength of the social network (total number of connections) that one depends on, and (2) the sum of the resources (capital, human and cultural) that each social network possesses. Studies find that a person with a better-connected network has more chances in job-matching channels, which may also be associated with higher incomes (Granovetter 1995; Sprengers 1988). As personal relationships are homogeneous in different groups (e.g. ethnic, religious), job opportunities acquired via personal relationships can cause inequalities in society (Behtoui 2004). Campbell et al. (1986) indicate that networks are resources and, like many other resources, are not distributed evenly. Sprengers (1988) studied 242 Dutch men, aged 40–55, who became unemployed in or before 1978. They conclude that those with better social capital found a job within a year, especially those with access to social capital through weak ties. Furthermore, Lin et al. (1981) find that a person who uses information from—and the influence of—powerful, wealthy or prestigious people are more likely to find a better job than those without such connections. In the present study, we aim at retesting the assumption of Behtoui (2004) for the second-generation migrants with only one parent being a Dutch native.

There are two neoclassical economic models that are able to explain the labor market gaps between immigrants and natives from the demand side. The first is the taste model developed by Becker (1957), and the second is statistical discrimination pioneered by Phelps (1972) and Arrow (1973). According to Becker’s model, discrimination is fundamentally a problem of taste, meaning that there is a disamenity value in employing a person, while, according to Phelps and Arrow, it is due to lack of information about the productivity of individuals. This gives the firms an incentive to use observable characteristics, such as race, gender, etc., to infer the expected productivity of applicants. However, the second model is not free from criticism (for an overview, see Aigner and Cain 1977). As it is difficult to measure discrimination empiricallyFootnote 3 in the labor market, scholars adopt the conventional discrimination measure, namely the effect of “otherness” on wage and employment to explain the differences between immigrants and natives (Chiswick 1978; Behtoui 2004). Foreign background is negatively related to employment and wages, especially for those outside the OECD circle (Miles 1993).

In this paper, we start by the dividing the immigrants into first- and second-generation, and then into two groups, namely, those with roots in OECD countries, and those with roots in non-OECD countries. The motivation behind this selection is the cultural similarity of OECD countries with the Netherlands, while non-OECD nationals have a incomparable culture with the Netherlands. Through this distinction we would like to capture the possible risk of suffering from discrimination (Miles 1993). Next, having a foreign background is associated with lower wages and employment, especially for those from non-OECD countries (Behtoui 2004). Furthermore, we also examine the effect of having a foreign-born father or mother from OECD or non-OECD countries for the second-generation migrants in order to test Chiswick (1977) and Behtoui (2004) hypothesis. Based on Chiswick (1977) hypothesis, a foreign father is more likely have to migrate for the sake of his own economic reasoning, and therefore, he does not represent a random sample of men from his country of origin. We focus on highly-educated migrants who have completed their studies together with natives in the same year, and who then entered the labor market. Thus, we have hardly any skill bias in our analysis. Before presenting the empirical results, we discuss the data set and carry out some descriptive analyses. The next section presents a brief description of the data used.

3 Data source and descriptive analysis

Our data originates from the Research Center for Education and the Labor Market (ROA) of Maastricht University in cooperation with DESAN Research Solutions. The relevant graduates have all the same higher education level, i.e., there is no selection bias via-a-vis their current status as starters on the labor market. Yet, informally, they carry their history of different cultural background, and this may also relate to different abilities at the same higher education institutions, and finally end up at different spatial locations.

The survey is based on the cohort of students from all higher professional educationFootnote 4 in the Netherlands who graduated in the period 2006/2007 to 2009/2010 after their higher professional training. Graduates were surveyed after a period of approximately 18 months, after they had completed their studies, and information was collected not only on their discipline of study and other aspects of their background, but also on their current job. Together with this, spatial information was also collected. The average response rate was 37 % for each year. Furthermore, we focus on graduate students who both had obtained their degree and have a full-time job. Therefore, we dropped from our analysis those graduates who had part-time jobs, were self-employed, were still students, and whose answer sheets had missing information.

For the students who have graduated from higher education, data are available on a series of variables including: personal characteristics (such as gender, age and ethnicity), subject of study, mode (full-time vs. part-time), degree results at the time of graduation, whether individuals are employed in (i) small firms (1–9 employees), (ii) medium-size firm (10–99 employees), or (iii) large firms (\(\le \)100 employees); graduates were also asked to give information about their place of residence, for instance: where they lived when they were 16 years old; where they lived during their course of study; and where they were now? Through an analysis of these questions, we could generate four variables, namely: lived in Noord Holland, Zuid Holland, Utrecht, (NH, ZH, U); moved to (NH, ZH, U); left (NH, ZH, U), and moved in-between (NH, ZH, U). Each of the aforementioned provinces (Noord Holland, Zuid Holland, Utrecht) hosts one of the major cities (Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague, and Utrecht); the total area connecting these cities are called the Randstad in Dutch.

Table 1 presents the personal characteristics of graduates with a higher professional education. The gender composition is 53 % male and the mean age of the graduates is 27 years. The share of second-generationFootnote 5 migrants is higher (8.6 %) compared with first-generation migrants (3.4 %). We also added three dummies to capture the differences between natives, OECD nationals and non-OECD nationals. As can be observed from Table 1, the share of non-OECD (7.6 %) nationals is higher compared with OECD nationals (4.4 %).

Regarding the graduation scores, Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for natives, and first-and second-generation migrants. The share of the first-generation migrants in the high graduation marks is slightly higher than that of the second generation. This suggests that the first-generation migrants are more talented than the second-generation migrants. A possible reason for higher marks of the first-generation migrants might be that some of these students came into the Netherlands already with a degree from their country of origin, and, since their original degree is sometimes not considered to be equivalent to a Dutch degree, they have to re-study for a couple of years.

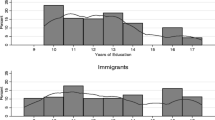

Figure 2 below shows the ratio of supplyFootnote 6 and wages for natives-immigrants in different age categories of graduates with a higher professional education. As expected, the supply ratio of first-generation migrants is low in the younger age groups (20–24), but, interestingly, they get higher wages. As we move further along the age line, the supply ratio of first-generation migrants to native increases, and the wage ratio gets below 1, indicating that older migrants are not paid as much as natives of the same age in the labor market. For the second-generation immigrants, there is no wage difference with natives, and even at older ages, the second-generation migrants receive slightly higher wages compared with natives.

4 Estimation of the Mincer equation

The Mincer equation (Mincer 1974) is often used in economics to analyse wage variation. This equation relates wages to a series of personal, work, and regional characteristics, and performs well in explaining the positive relationship between ability (proxied by years of education) and earnings. In the Mincer equation, it is assumed that the logarithm of earnings is a nonlinear function of experience, and, according to the model, it can be measured as age minus years of schooling, minus the school starting age (5 years). In this study we do not have information on total years of education. Therefore, we use age and age squared as proxies for experience. Furthermore, we also include the subject of study in the form of seven dummies for graduates with higher professional training.Footnote 7 We introduce also a dummy variable taking the value of 1 if the individual is responsible for controlling other employees, i.e. he/she is a ‘supervisor’, and 0, otherwise. Furthermore, to control for the language of the graduates, we use a dummy taking the value of 1, if a language other than Dutch is spoken inside the household.

The regression equation for graduates with a higher professional education is written as:

where (w\(_\mathrm{it})\) is the gross monthly salary of individual (i) in year (t); X\(_\mathrm{{i,t}}\) represents the explanatory variables that include the graduation score,Footnote 8 age (a proxy for experience), age-squared to capture nonlinear effects, dummies for gender, field of study, and residential location; Z\(_\mathrm{{i,t}}\) is a dummy for immigrant status; and \(\in _{i,t} \) is the error term. We use residential and time fixed effects to cope with spatial and temporal heterogeneity. We follow four steps in our estimations. In the first step, we include the main variables, while in the second step, we separate age and age squared for the first- and the second-generation immigrants. In the third step, we add the interaction between the first and second-generation migrants with different size classes of firms. And, finally, in the fourth variant we add dummies for the field of study.

5 Empirical evidence

Table 3 shows the empirical results. There appears to a wage gap between genders (male and female) who are equally educated; male graduates receive 8 % more gross salary per month than their female counterparts, but the outcome appear to improve a bit (7 %) when we control for the field of education. We consider full-time jobs only, and therefore, the gender difference cannot be explained by the difference in working hours.

The age variable, which is used as a proxy for experience, is positively related to our dependent variable, and is highly significant in all three variants. The estimated coefficients are comparable with the values generally found in the literature. Furthermore, as the descriptive analysis show (Sect. 2), the first-generation migrants experience a difference in their gross salary per month, if they graduate at later age. To capture this age effect, we separated the age and age squared for the first- and the second-generation immigrants; the interpretation of our result is presented in Fig. 3 below. As can be observed from Fig. 3, there is no significant wage difference with age category between the second-generation immigrants and the native graduates. Clearly, if we compare native graduates with the first-generation immigrants, we can observe that the older the age category of the first-generation immigrants, the lower the wages. This indicates that, for the first-generation immigrants who are investing in their human capital at later age, the returns to their education get smaller compared with the natives and the second-generation immigrants of the same age.

The human capital measure indicates that talented graduates receive higher wages in the labor market compared with our reference case (where the graduation score is below 7.5). Graduating with marks between 9 and 10 increases the monthly gross salary by 5 % compared with our reference category, ceteris paribus. For those who graduated with scores between 7.5 and 8.5, the difference is 3 %.

The social structure variable, which contains our variables of interest, indicates that first-generation migrants earn lower wages, leading to a 3 % wage gap between natives and the first-generation migrants. Our finding for the first-generation migrants is in line with the literature: that is, the wage gap is mostly related to language and social skills (Chiswick 1978). Our result confirms previous study findings: for example, Algan et al. (2010) find for France, Germany and the United Kingdom that first-generation migrants who are living and working in the above-mentioned countries earn significantly less than the natives, and for those who come from developing countries, their wage gap increases further. Furthermore, second-generation migrants are equally paid in the labor market, and this group of migrants in general does not suffer a wage difference. Our empirical result for non-OECD countries indicates that the wage gap between graduates from OECD members and non-OECD countries is 1 %. Furthermore, a possible reason for the wage difference between OECD and non-OECD graduates may be that graduates from non-OECD countries accept lower paid jobs to remain in the Netherland. A study by Bijwaard and Wang (2013) finds that graduate students from less developed countries accept lower paid jobs to remain in the country and find better job opportunities.

An important factor that affects wages according to the efficiency wage theory is the size of the firm (Akerlof 1982; Bulow and Summers 1986). Our empirical finding shows that wages increase with firm size. Medium-sized and large firms pay respectively, 2 and 6 % more gross salaries than our reference category (small firms). The second-generation immigrant earns higher wages in both medium-sized and large firms compared with the second-generation immigrant graduates employed in small firms. Furthermore, employees with more responsibility receive higher wages compared with those without.

As indicated above in the data section (Sect. 2), we created four variables for residential location to determine whether residential location has an impact on the gross salary of these graduates. The results indicate that those who lived in the provinces of Noord Holland, Zuid Holland and Utrecht (NH, ZH, U) receive 4 % more gross salary compared with our reference variable (which refers to those living and continuing to live in other provinces). Furthermore, those who are moving into the mentioned provinces are also receiving higher wages, while their gross monthly salary increases by 3–4 %. Interestingly, for those graduates who are moving between the aforementioned provinces, their gross monthly salary increases by 6 % in comparison to our reference variable. Venhorst (2012) studied the wages of college and university graduates in the Netherlands, and found that wages are higher for those graduates who work in larger labor markets and expensive regions. Furthermore, those who move away from the aforementioned provinces, have a higher gross salary compared with the reference group. These results are in line with the literature that indicates that those graduates who change their location fare better than those who do not change location (Abreu et al. 2015).

We also controlled for field of education, and our results indicate that those who study technical studies are paid the highest (17 %) compared with our reference category (language and arts). All coefficients for the field of study are positive and significant, which indicates that graduates of language and arts courses are employed in less well-paid jobs.

The impact of parent’s roots

Taking into account the conventional discrimination measures applied by Chiswick (1977), having a native-born mother contributes more to language skills than a native-born father, and, as a result, individuals can earn higher wages. However, Behtoui (2004), with reference to a Swedish case, finds that since fathers can occupy higher positions in the labor market than mothers, a native-born father can pass on a more valuable social network to his children than a native-born mother. We test both hypotheses by categorizing individuals’ parents as coming from either OECDFootnote 9 or non-OECD countries. Through this distinction we can observe the differences in culture, language and quality of the parents’ education and its impact on the productivity of individuals in the labor market.

Table 4 above shows the share of each category of immigrants in terms of their parents’ roots (i.e. country of origin). In the first-generation immigrants, the share of graduates from non-OECD countries is higher compared with the other categories (OECD, father from OECD, mother from OECD), and this share is the second highest in the second-generation immigrants. This is not surprising, because, after the Second World War, the Netherlands hosted a large number of guest workers from non-OECD countries. Table 4 also shows that the share of children born from marriages between Dutch nationals (both male and female) and non-OECD nationals is relatively higher compared with the share of marriages with OECD nationals.

Table 5 presents the results concerning the wages of higher education graduates after correcting for their parents’ roots. We estimated wages in two variants, but because of space limitation, we only report here the parents’ roots variables. The first variant does not control for field of education, while the second does. Our result for the second generation of immigrants indicates that, if individuals have a native father or native mother in combination with a non-OECD national mother (−2.6 %) and an OECD father (−2.5 %), they are earning lower wages compared with our reference category (where both parents are Dutch nationals). The results suggest that having either a native father or mother and access to their social capital does not affect the labor market outcome of these young graduates compared with the case where both parents are natives. The difference between having a native mother or a native father is very small in our estimation, but still our results confirm Behtoui’s (Behtoui 2004) results that graduates with a native father perform better (the difference is between 0.0045 to 0.0059 %) than a native mother, even though they probably would speak a different language at home.

The difference between those young graduates who have roots from OECD countries and those with roots in non-OECD countries shows that having non-OECD parents decreases their wages by 2 % compared with the reference case (where both parents are Dutch natives), ceteris paribus. The finding for OECD and non-OECD parents captures the culture and language differences on the one hand, and the parents’ quality of education, on the other.

The first-generation immigrants follow a pattern that is similar to what we have just described for the second-generation migrants. Young graduates with roots in non-OECD countries experience labor market disadvantages, which are twice as high as those of young graduates with roots in OECD countries. Furthermore, this also highlights, the effect of “otherness” due to one’s name and family name. We can conclude that acquiring Dutch human capital, Dutch-specific skills, language, and even integration in the long-term for some people in the Netherlands, especially those with a more extensive cultural background, does not overcome wage differences in the labor market.

Robustness check

In order to check the robustness of our OLS regression on the wage difference between the first- and second-generation immigrants and natives, we employed two different methods. Firstly, we dropped some of the variables such as: different firm sizes, graduation score and supervisor position from our analysis, because there was a concern on the endogeneity of these variables with our dependent variable. Secondly, we used the logarithm of gross hourly wages as a dependent variable. Table 6 presents our results in two variances; the first variance-dependent variable is monthly gross salary, while in the second variance as indicated it is gross-hourly wage.

As can be observed, the results are similar to the ones we found in Table 3. Secondly, we ran a quantile regression. The quantile regression also confirms our OLS results. The first-generation immigrants in fact receive lower gross wages with a magnitude of \(-3\) percent per month. As can be observed from Figure 4 below, the coefficient confidence interval in the quantile regression for both first- and second-generation immigrants does, for the most part, not cross the confidence interval of the OLS regression. Therefore, we can conclude that the quantile regression results are not significantly different from the OLS results.

6 Conclusion

In this study we have investigated wage differences between immigrants (first- and second-generation) and natives, and the extent to which the immigrant background has an impact on the labor market outcome of graduates with higher professional education who have full-time jobs. Our empirical results indicate that, even when migrants are educated equally well as natives, there is still a wage gap between first-generation migrants and second-generation with roots in non-OECD countries and natives in the Netherlands. Our empirical findings indicate that for groups of people, especially those with roots in non-OECD countries, acquiring Dutch human capital does not overcome the wage differences. Furthermore, graduation age plays a significant role in wage discrimination, in particular for the first-generation immigrants. The first-generation immigrants who start to invest in their human capital at later ages experience more wage discrimination compared to those who invest at younger ages.

We also find that there is a monthly gross income gap between males and females. This is even larger than the wage gap between the first- and the second-generation migrants and the natives. The female graduates who are employed full-time and graduated with equal scores as their males counterparts receive between 7 to 8 % less monthly gross salary compared to male graduates with the same labor market supply characteristics.

The literature indicates that graduates who change their location fare better than those who do not change location. Our results confirm the findings of previous studies, and also add new information to the emerging literature, regarding the people who move from one big city to another. These people earn higher wages compared to the rest of the categories.

We also compared individuals according to their parents’ roots: those who have roots in OECD countries and those who have roots in non-OECD countries. We found that for the second-generation immigrants, having roots in non-OECD countries (mainly referring to those individuals with both parents from non-OECD countries) is negatively related to wages. So, when both parents are from outside the OECD, their wages are lower by approx. 2 %. This indicates that neither the parents’ acquisition of specific-Dutch labor market knowledge due to long duration of residence, nor the graduates’ acquisition of Dutch-specific human capital are able to overcome labor market wage differences. The same result is found for the first-generation immigrants with roots outside OECD countries. Further research on the effect of social capital—and specifically on the parents’ roots—is needed to divide both the first- and the second-generation immigrants into more detailed groups. However, in our research context it was very hard to make this categorization because of the limited number of observations. Further research is also needed to find out whether the wage gap of migrants is due to discrimination in their labor contract or due to differences in personal contacts (the impact of social capital).

Notes

Migrants coming from non-OECD countries may find that their university or college degree is not considered equivalent to a Dutch degree. Therefore, they need to re-study and upgrade the degree obtained in their homeland.

Maastricht University collects information on graduates from higher professional institutions (in Dutch it is called HBO), and universities graduates from the entire country.

This is because factors such as race, skin colour, hair colour etc may have a significant impact on discrimination, and we do not control for them.

This does not include university graduates.

The supply ratio refers to the total number of graduated migrants divided by total graduated natives.

For more information on the descriptive statistics, we refer to Table 7 in Appendix.

For details, see Footnote 2.

We have a lower share of migrants in our analysis; therefore, their classification into detailed ethnic backgrounds is not possible because of the lower number of observations. Thus, we distinguished them into bigger groups, like OECD and non-OECD.

References

Abreu, M., Faggian, A., McCann, P.: Migration and inter-industry mobility of UK graduates. J. Econ. Geogr. 15, 353–385 (2015)

Aigner, D.J., Cain, G.G.: Statistical theories of discrimination in labor market. Indus. Labor Relations Rev. 30, 175–187 (1977)

Akerlof, G.A.: Labor contracts as partial gift exchange. Q. J. Econ. 97, 543–569 (1982)

Alders, M.: Classification of the population with a foreign background in the Netherlands. Division of Social and Spatial Statistics, Department of Statistical Analysis of Population Voorbug, Statistics Netherlands (2001)

Algan, Y., Dustmann, C., Glitz, A., Manning, A.: The economic situation of first and second-generation immigrants in France, Germany and the United kingdom. Econ. J. 120, 4–30 (2010)

Arrow, K.J.: The theory of discrimination. In: Ashenfelter, O., Rees, A. (eds.) Discrimination in Labor Markets, pp. 3–33. Princeton University Press, Princeton (1973)

Becker, S.G.: The Economics of Discrimination. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1957)

Becker, S.G., Becker, N.G.: The Economics of Life: From Baseball to Affirmative Action to Immigration, How Real-World Issue Affect Our Everyday Life. McGraw-Hill, New York (1998)

Behtoui, A.: Unequal opportunities for young people with immigrant backgrounds in the Swedish labour market. Labour 18, 633–660 (2004)

Bijwaard, G.E., Wang, Q.: Return migration of foreign students. IZA Discussion Paper 7185 (2013)

Borjas, G., Katz, L.: The Evolution of the Mexican-Born Workforce in the United States. In: Borjas G. (eds.) Mexican Immigration to the United States. National Bureau of Economic Research Conference Report, Cambridge, MA (2007)

Borjas, G.: The labor demand curve is downward sloping: reexamining the impact of immigration on the labor market. Q. J. Econ. 118, 1335–1374 (2003)

Borjas, G.J.: Assimilation, change in cohort quality, and the earnings of immigrants. J. Labor Econ. 3, 463–489 (1985)

Bourdieu, P., Wacuant, J.D.L.: An Innovation to Reflexive Sociology. Blackwell Publishers, Oxford (1992)

Bovenkerk, F., Gras, M.J.I., Ramsoedh, D.: Discrimination against migrant workers and ethnic minorities in access to employment in the Netherlands. International Labour Organization, Geneva (1995)

Bulow, J., Summers, L.: A theory of dual labor markets with application to industrial policy, discrimination, and Keynesian unemployment. J. Labor Econ. 4, 376–414 (1986)

Campbell, K.E., Marsden, P.V., Hurlbert, J.S.: Social resources and socioeconomic status. Soc. Netw. 8, 97–117 (1986)

Chiswick, B.R.: Sons of immigrants: are they at an earnings disadvantage? Am. Econ. Rev. 67, 376–380 (1977)

Chiswick, B.R.: The effect of Americanization on the earnings of foreign-born men. J. Polit. Econ. 86, 897–921 (1978)

Chiswick, B.R., Miller, P.W.: The international transferability of immigrants’ human capital. Econ. Educ. Rev. 28, 162–169 (2009)

de Coulon, A.: Wage differentials between ethnic groups in Switzerland. Labour 15, 111–132 (2001)

Eurostat (2010) Statistics in focus. 34/2011. Accessed 24 March 2013

Foged, M., Peri, G.: Immigrants’ effect on native workers: new analysis on longitudinal data. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 8, 1–34 (2015)

Friedberg, R.: You can’t take it with you? Immigrant assimilation and the portability of human capital. J. Labor Econ. 18, 221–251 (2000)

Granovetter, M.: Getting a Job: A Study of Contacts and Careers. University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1995)

Groot, S.: The impact of foreign knowledge workers on productivity. Chapter in: S. Groot, Agglomeration, globalization and regional labor market. pp. 137–165. PhD thesis. Vrij Universiteit Amsterdam (2013)

Lin, N., Vaughn, J.C., Ensel, W.: Social resources and occupational status attainment. Soc. Force 59, 1163–1181 (1981)

Miles, R.: Racism after ‘race relations’. Routledge, London (1993)

Mincer, J.: Schooling, Experience and Earnings. Columbia University Press, New York (1974)

Nijkamp, P., Poot, J., Sahin, M. (eds.): Migration Impact Assessments: New Horizons. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham (2012)

Ottaviano, I.P.G., Peri, G.: Rethinking the effect of immigration on wages. J. Eur. Assoc. 10, 152–197 (2012)

Phelps, E.S.: The statistical theory of racism and sexism. Am. Econ. Rev. 62, 659–661 (1972)

Sprengers, M., Tazelaar, F., Flap, H.D.: Social resources, situational constraints, and reemployment. Neth. J. Sociol. 24, 98–116 (1988)

Venhorst, A.V.: Smart move? The spatial mobility of higher education graduates. Ph.D thesis. Rijksuniversiteit Groningen (2012)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

P. Rietveld passed away on November 1, 2013.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Gheasi, M., Nijkamp, P. & Rietveld, P. Wage gaps between native and migrant graduates of higher education institutions in the Netherlands. Lett Spat Resour Sci 10, 277–296 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12076-016-0174-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12076-016-0174-6