Abstract

Biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma (BSNS) is a rare malignant tumour of the upper nasal cavity and ethmoid sinuses that presents predominantly in middle aged female patients and show a characteristic infiltrative and hypercellular proliferation of spindle cells that demonstrate a specific immunoreactivity. We present three cases with BSNS that had different presenting complaints, either sinonasal or orbital problems, underwent endoscopic surgical treatment and/or radiotherapy and have been disease free on long follow up. A systematic review of all published cases was performed to identify all BSNS cases known at present. BSNS requires prompt and correct diagnosis with accurate surgical resection as well as consideration of radiotherapy. Our three cases confirm the findings of the literature and support that BSNS is an aggressive but treatable malignant disease of the sinonasal tract.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There is a wide variety of sinonasal tumours with multiple presentations, phenotypes and symptoms. Sinonasal malignancies are a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge due to histologic diversity and proximity to vital structures like the orbit, skull base, brain and cranial nerves. Biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma (BSNS) is one of the rarest and slow growing soft tissue sarcomas that has been only described in the last decade [1]. The morphologic features, the high recurrence rate but only locally without distant metastases and immunohistochemical and molecular findings demonstrate a highly differentiated tumour that requires thorough care [2]. The uniqueness of this tumour as well as its novelty requires further investigation and report of cases to ensure correct diagnosis and management in the future.

Material and Methods

A thorough systematic review of the literature was conducted by two electronic databases Medline/Pubmed (1946–December 2022) and Embase databases (1947–December 2022) using the Ovid research tool. The research terms used were “biphenotypic”and “sinonasal” and “sinus” and “nasal” and “sarcoma” creating the MeSH terms respectively. A systematic review flowchart was created and followed to ensure coherence. Only 52 results were identified with the research terms described and abstract assessment led to inclusion of 27 articles that were either case reports or reviews of the existing literature. Studies or case reports that had doubtful results or did not confirm BSNS diagnosis were excluded from the search. Non English language articles were excluded from the search. Table 1 summarises the BSNS cases identified in the literature with main findings and key points of their age/gender, presentation and symptoms, site of lesion and extension, treatment modalities, recurrence rates and main genetic findings.

Cases

Case 1

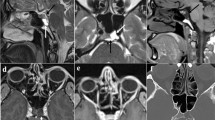

We present a 52 year old lady that suffered with exophthalmos symptoms and was initially assessed by ophthalmology specialists. During her investigation process, she underwent a CT scan of her orbits and sinuses that revealed an ossified hard tumour extending from the sinonasal tract until the cribriform plate and into the orbit, pressing the rectus medialis and the orbital fat causing exophthalmos (Fig. 1a, b). Office biopsy was most consistent with a low-grade spindle cell carcinoma. An endoscopic resection of the tumour was performed adopting the cavitation technique for complete removal of the mass. More specifically, after tumor debulging a middle meatal antrostomy, and complete ethmoidectomy provided access into the intraorbital part. The middle turbinate was removed to ensure free margins of the histological specimen. The ossification of the tumour worked as an adjunct towards its complete removal and there was also reassurance of the clear margins of the resection in the histology report that prevented this lady from having post-operative radiotherapy. Final pathology returned as BSNS characterized by a low cellular proliferation of spindle cells arranged in interwoven fascicles with major calcification. She was therefore followed up with a MRI scan of her orbits and sinuses that showed clearance of the disease observed 7-year postoperatively (Fig. 1c).

Case 2

Α 30-year old lady who presented with pressure symptoms of her orbit resulting in bulb protrusion without any other complaints. She underwent a CT scan of her orbits and sinuses that revealed a tumour in the maxillary sinus with orbital floor destruction and intraorbital extension (Fig. 2a). Primary biopsy was most consistent with a low-grade spindle cell carcinoma. An endoscopic resection of the tumour was performed via a medial maxillectomy and anterior ethmoidectomy. Intra-operative frozen sections from adjacent anatomical structures were negative for malignancy. Final pathology revealed a BSNS characterised by moderate to highly cellular proliferation of spindle cells arranged with focal rhabdomyoblastic differentiation. This lady had subsequent radiotherapy since at the time of the diagnosis the tumour had already spread into the orbit and the resection was challenging due to the proximity to the infraorbital nerve that was eventually preserved. She was also followed up with MRI scan that 6 years after her surgery show no local recurrence of the disease (Fig. 2b).

Case 3

The third case is summarised in a 47 year old lady who presented with severe recurrent headaches as her main concern. She underwent a CT scan of her paranasal sinuses that revealed a mass extending in the middle meatus involving the orbit and the anterior skull base (Fig. 3a). Primary biopsy was most consistent with a low-grade spindle cell malignant tumor. An endoscopic transnasal approach was used for gross tumor resection. Intraoperatively, the mass was found to extend superiorly to involve the cribriform plate, medially the nasal septum and was laterally adherent to the lamina papyracea. After unilateral middle meatal antrostomy, complete ethmoidectomy on both sites, the superior nasal septum was removed and a type three drainage of the frontal sinus was performed. The lamina papyracea of tumor site was removed and the cribriform plate and crista galli were resected, resulting in a small dural defect with a low flow cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak. This was repaired with a fascia lata graft and a local mucoperiostal flap from the contralateral septum which can be rotated to resurface the skull base defect (flip-flap). Intraoperative margins returned negative. Histopathology of the tumor confirmed diagnosis of BSNS. The patient was also decided to have radiotherapy to complete her treatment since the disease was progressed at the time of diagnosis. In her 4-year follow up, she appears to be disease free and has no headaches or other sinonasal symptoms (Fig. 3b).

Discussion

Sinonasal tract tumours are neoplasms that affect mostly the sinuses, internal nasal cavities, orbits, skull base and in some cases can have intracranial extension. Common presenting symptoms are nasal obstruction, epistaxis, facial pressure or pain, smell impairment, as well as neurological or ophthalmic complaints due to the tumour’s extension [25, 26]. In our cases, the main symptoms were headaches or macroscopic changes of the eye orientation. The diversity of sinonasal tumours makes their identification and diagnosis challenging due to the large spectrum of their clinical presentation as well as the the histopathological origin that can be neurogenic, myogenic, fibroblastic, vascular or can even reveal benign reactive proliferation.

Biphenotypic sinonasal sarcomas were firstly discovered by Lewis et al. in 2012 [27], who described them as low grade spindle sarcomas of the sinonasal tract. WHO announced addition of this entity in the reviewed 2017 WHO classification of head and neck tumours including BSNS as one of the newly discovered tumours of the sinonasal cavity [28,29,30]. These tumours have double neural and myogenic differentiation but are histologically different from malignant sarcomas or other sinonasal cancerous masses. The primary different characteristic of this group is the biphenotypic marker expression during the immunohistochemical analysis as well as its unique identity combining clinical, morphologic, histologic and genetic features. In our cases, all three patients presented with generic sinonasal symptoms and initially underwent routine investigations, primarily CT and MRI scan of their orbits and sinuses as well as flexible nasoendoscope to assess the nature of the sinonasal masses. Although the above are all adjuncts to a thorough surgical planning for mass excision, they have minimal to offer towards determining the diagnosis. In all BSNS cases, imaging modalities and endoscopic investigations reveal an enhancing soft tissue mass with infiltrative growth associated with hyperplastic bone or even bone infiltration. It is therefore evident that minimal features exist to guide the ENT surgeon towards BSNS as these entities present similar to other nerve sheath tumours, mesenchymal neoplasms and other varieties of sarcomas [31]. It is therefore histological, immunochemical and genetic analysis which is required to confirm diagnosis of BSNS.

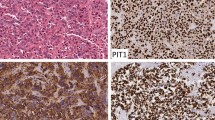

BSNS histopathological analysis reveals a spindle cell carcinoma that infiltrates the surrounding tissues including the nasal bones [32]. It is mostly unencapsulated and macroscopically gives the impression of a polypoid mass [13]. Microscopically, the spindle cells are organised in fascicles with all nuclei arranged in the same direction mimicking a herringbone pattern. There are no foci and tumour cells mostly lie on a fragile collagenous matrix with minimal mitotic activity[9]. In our cases, all three tumours had macroscopic features of a normal polyp with no ulceration, haemorrhage or necrosis and no characteristics of malignancy while erosion of bone and destruction of surrounding tissues was observed on imaging modalities. The histopathological analysis showed BSNS with small sinonasal-type glands, lymphocytes and macrophages with an increased vascular network, features that are typical of BSNS according to the literature.

However, the important finding that determined the diagnosis was smooth muscle actin (SMA) and S100 positivity with EMA and CD34 negativity during the immunohistochemical analysis [13, 24]. Normally, BSNS tumours show immunoreactivity for S100, SMA and sometimes desmin but demonstrate no reaction with CD34, STAT6, EMA and myogenin, which was also included in the report of all three cases presented. According to the literature and histological reports for BSNS mentioned in all 52 articles reviewed, it is evident that the BSNS is consistently positive for S100, calponin, actin, factor XIIIa and β-catenin; in some cases positive for myogenin, desmin, cytokeratins and EMA; and it is always negative for SOX10 [23, 33].

In terms of genetic analysis, PAX3 and MAML3 are genes involved in BSNS and their mutations may lead to different presentations of the disease or even different sinonasal mesenchymal tumours [17]. MAML3 is one of the mastermind-like (MAML) family of transcriptional co-activators that contribute to significant stages of cell life cycle such as cell proliferation, differentiation and death. Genetic analysis is performed using the FISH technique followed by PCR focusing on PAX3 re-arrangement atypias. PAX3 and MAML3 fusion is most commonly seen in BSNS while combinations such as AX3-FOXO1, PAX3-MAML1, PAX3-MAML2, PAX3-NCOA1, PAX3-NCOA2 and PAX7-MAML3 are also observed. To make differential diagnosis more challenging, most of the above combinations exist in various sinonasal sarcomas such as the PAX3-FOXO1 and PAX3-NCOA1 that exist in rhabdomyosarcomas. However, the pathognomonic finding of PAX3-MAML3 fusion transcript is an adjunct towards BSNS diagnosis [17, 34]. Interestingly, it emerges from the literature that different combinations lead to various presentations of BSNS with characteristic tumour site or extension or even affecting the recurrent rates. In order to achieve such results though, more cases with genetic testing are required to gain safe and reliable information on how genetics affect clinical variations [35]. Unfortunately, our histopathology team did not proceed to genetic testing, however BSNS has unique histological and immunohistochemical findings that lead towards the correct diagnosis as seen in various other cases in the literature where FISH genetic testing could not be performed.

Regarding treatment modalities, all cases in the literature were treated with surgical excision either endoscopic or open using craniotomy or lateral rhinotomy as an access point with or without adjuvant radiotherapy with some cases receiving chemotherapy as well (Table 1). Recurrence was observed in both groups irrespective of having adjuvant radiotherapy post operatively. There is therefore, no important evidence in the current literature to argue towards concomitant radiotherapy or surgical excision alone [5, 36]. In the literature, BSNS show significant extrasinonasal extension (approximately 27%) with the most common site of extension to be the cribriform plate. Local recurrence rate is considered high but fortunately, no distant metastasis was observed in any case with BSNS in the literature. In our cases, orbital and skull base involvement was observed, however radiotherapy was selected only according to intra-operative findings regarding the tumour infiltration of surrounding tissues. Despite having only endoscopic resection of the tumour that was invading the orbital fat, the patient in case 1 has no recurrence on their 7-year follow up, even without receiving adjuvant radiotherapy. It is therefore mindful to advocate, that radiotherapy should be individually selected in patients with spreading tumours and difficulties in complete endoscopic resections and should always be a result of multidisciplinary team discussion and involvement of patient views in the decision. The rarity of the disease and the small number of cases described in the literature limit the accurate assessment of treatment efficacy and more data is needed.

Conclusion

Biphenotypic sinonasal sarcomas are uncommon low-grade spindle cell carcinomas in the sinonasal tract that demonstrate positive myogenic and neural differentiation. The clinical importance of these tumours is summarised to their common symptoms in association with the non-specific radiological findings but their high local recurrence rates that makes the early diagnosis and full treatment critical. Additional radiotherapy should always be a consideration but individualised treatment according to clinicopathological features of the tumour is key. Treatment with radiotherapy is individualised and is supported by concrete criteria based on location of the tumour, intraoperative surgical margins, histopathological features and general condition of the patient. It is therefore crucial for the multidisciplinary team that consists of the ENT surgeon, radiologist and primarily pathologist as well as oncologist, to be aware of this sinonasal entity to correctly diagnose BSNS, avoid misdiagnosis and treat effectively and successfully the disease.

References

Chitguppi C et al (2019) Biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma-case report and review of clinicopathological features and diagnostic modalities. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base 80(1):51–58. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1667146

Carter CS, East EG, McHugh JB (2018) Biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma: a review and update. Arch Pathol Lab Med 142(10):1196–1201. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2018-0207-RA

Bartoš V, Rác P, Skálová A (2022) Biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma-a case report. Klin Onkol 35(5):402–406. https://doi.org/10.48095/ccko2022402

Nichols MM, Alruwaii F, Chaaban M, Cheng YW, Griffith CC (2022) "Biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma with a novel PAX3::FOXO6 fusion: a case report and review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-022-01479-w

Sudabatmaz EA, AkifAbakay M, Koçbıyık A, Sayın İ, Yazıcı ZM (2022) A rare sinonasal malignancy: biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma. Turkish Arch Otorhinolaryngol 60(1):53–58. https://doi.org/10.4274/tao.2022.2021-11-9

Baněčková M et al (2022) Misleading morphologic and phenotypic features (Transdifferentiation) in solitary fibrous tumor of the head and neck: report of 3 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol 46(8):1084–1094. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000001875

Georgantzoglou N, Green D, Stephen SA, Kerr DA, Linos K (2022) Biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma with PAX7 expression. Int J Surg Pathol 30(6):642–645. https://doi.org/10.1177/10668969221080082

Bell D, Phan J, DeMonte F, Hanna EY (2022) High-grade transformation of low-grade biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma: radiological, morphophenotypic variation and confirmatory molecular analysis. Ann Diagn Pathol 57:151889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2021.151889

Sethi S, Cody B, Farhat NA, Pool MD, Katabi N (2021) Biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma: report of 3 cases with a review of literature. Hum Pathol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehpc.2021.200491

Hanbazazh M, Jakobiec FA, Curtin HD, Lefebvre DR (2021) Orbital involvement by biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma with a literature review. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 37(4):305–311. https://doi.org/10.1097/IOP.0000000000001839

Gross J, Fritchie K (2020) Soft tissue special issue: biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma: a review with emphasis on differential diagnosis. Head Neck Pathol 14(1):33–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-019-01092-4

Miglani A, Lal D, Weindling SM, Wood CP, Hoxworth JM (2019) Imaging characteristics and clinical outcomes of biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol 4(5):484–488. https://doi.org/10.1002/lio2.305

Le Loarer F et al (2019) Clinicopathologic and molecular features of a series of 41 biphenotypic sinonasal sarcomas expanding their molecular spectrum. Am J Surg Pathol 43(6):747–754. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000001238

Dean KE, Shatzkes D, Phillips CD (2019) Imaging review of new and emerging sinonasal tumors and tumor-like entities from the fourth edition of the world health organization classification of head and neck tumors. Am J Neuroradiol. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A5978

Sugita S et al (2019) Imprint cytology of biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma of the paranasal sinus: a case report. Diagn Cytopathol 47(5):507–511. https://doi.org/10.1002/dc.24142

Alkhudher SM, Zamel HA, Bhat IN (2019) A rare case of nasal biphenotypic sino-nasal sarcoma in a young female. Annals Med Surg 37:4–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2018.08.015

Andreasen S et al (2018) Biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma: demographics, clinicopathological characteristics, molecular features, and prognosis of a recently described entity. Virchows Arch 473(5):615–626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-018-2426-x

Fudaba H, Momii Y, Hirano T, Yamamoto H, Fujiki M (2019) Recurrence of biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma with cerebral hemorrhaging. J Craniofac Surg 30(1):e1–e2. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000004720

Kakkar A, Rajeshwari M, Sakthivel P, Sharma MC, Sharma SC (2018) Biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma: a series of six cases with evaluation of role of β-catenin immunohistochemistry in differential diagnosis. Ann Diagn Pathol 33:6–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2017.11.005

Zhao M et al (2017) Clinicopathologic and molecular genetic characterizations of biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi 46(12):841–846. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-5807.2017.12.006

Lin Y, Liao B, Han A (2017) Biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma with diffuse infiltration and intracranial extension: a case report. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 10(12):11743–11746

Fritchie KJ et al (2016) Fusion gene profile of biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma: an analysis of 44 cases. Histopathology 69(6):930–936. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.13045

Rooper LM, Huang SC, Antonescu CR, Westra WH, Bishop JA (2016) Biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma: an expanded immunoprofile including consistent nuclear β-catenin positivity and absence of SOX10 expression. Hum Pathol 55:44–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2016.04.009

Huang SC et al (2016) Novel PAX3-NCOA1 fusions in biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma with focal rhabdomyoblastic differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol 40(1):51–59. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000000492

Bishop JA (2016) Recently described neoplasms of the sinonasal tract. Semin Diagn Pathol 33(2):62–70. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semdp.2015.12.001

Johncilla M, Jo VY (2016) Soft tissue tumors of the sinonasal tract. Semin Diagn Pathol 33(2):81–90. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semdp.2015.09.009

Lewis JT et al (2012) Low-grade sinonasal sarcoma with neural and myogenic features: a clinicopathologic analysis of 28 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 36(4):517–525. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182426886

Tatekawa H, Shimono T, Ohsawa M, Doishita S, Sakamoto S, Miki Y (2018) Imaging features of benign mass lesions in the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses according to the 2017 WHO classification. Jpn J Radiol 36(6):361–381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11604-018-0739-y

Thompson LDR, Franchi A (2018) New tumor entities in the 4th edition of the World Health Organization classification of head and neck tumors: nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and skull base. Virchows Arch 472(3):315–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-017-2116-0

Stelow EB, Bishop JA (2017) Update from the 4th edition of the world health organization classification of head and neck tumours: tumors of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and skull base. Head Neck Pathol 11(1):3–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-017-0791-4

Galy-Bernadoy C, Garrel R (2016) Head and neck soft-tissue sarcoma in adults. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 133(1):37–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anorl.2015.09.003

Purgina B, Lai CK (2017) Distinctive head and neck bone and soft tissue neoplasms. Surg Pathol Clin 10(1):223–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.path.2016.11.003

Bishop JA (2016) Newly described tumor entities in sinonasal tract pathology. Head Neck Pathol 10(1):23–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-016-0688-7

Jo VY, Mariño-Enríquez A, Fletcher CDM, Hornick JL (2018) Expression of PAX3 distinguishes biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma from histologic mimics. Am J Surg Pathol 42(10):1275–1285. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000001092

Wang X et al (2014) Recurrent PAX3-MAML3 fusion in biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma. Nat Genet 46(7):666–668. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2989

Kominsky E, Boyke AE, Madani D, Kamat A, Schiff BA, Agarwal V (2021) Biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma: a case report and review of literature. Ear Nose Throat J. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145561321999196

Funding

Open access funding provided by HEAL-Link Greece.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Human or Animal Rights

All three patients that were included in this project were informed and consented verbally for the anonymous publication of their health data.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Anastasiadou, S., Karkos, P. & Constantinidis, J. Biphenotypic Sinonasal Sarcoma with Orbital and Skull Base Involvement Report of 3 Cases and Systematic Review of the Literature. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 75, 3353–3363 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12070-023-03900-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12070-023-03900-4