Abstract

Supply chain (SC) adaptability (SC-Ad) implies that SC processes should change and adapt to anticipated structural and market changes. However, when these changes are related to shifts from exploitative to explorative focuses, companies face an inflexibility problem because of involved uncertainties, creating a barrier to obtaining SC-Ad. This research proposes to overcome this barrier by integrating new combinations of the product/market strategy and SC processes and securing their fit over time. To get it, this study proposes two SC-Ad drivers (related to the SC process (ASCOS) and new product development competences (PDC)), which secure the aforementioned fit by reducing its uncertainties and thus ensuring a SC-Ad that responds to emerging competitive changes. Measurement and structural models were assessed following PLS-SEM. ASCOS and PDC’ relative importance was analyzed using the importance/performance/analysis procedure. PLS, PLS-predict, and CVPAT were used to analyze model’s in-sample and out-of-sample predictive capacity. ANOVA was used to compare SC-Ad, ASCOS and PDC in different plant groups. Results suggest that ASCOS and PDC are SC-Ad’s drivers, and that the plants with highest SC-Ad values are those with the higher ASCOS and PDC’ values. This expand knowledge about SC-Ad drivers, which represents an important literature gap. In an indirect way, some new light is also added to the topic of ambidextrous management. The adequate generalizability of these results is supported by a) a wide multi-country, multi-informant, and multi-sector sample of 268 plants, b) a good out-of-sample model predictive capacity c) no heterogeneity issues.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Supply chain adaptability (SC-Ad) is defined as the capability of directing and enabling supply chains (SC) to adapt its strategies, products, processes and/or technologies to structural changes in the market (Fisher 1997; Lee 2002, 2004; Ivanov et al. 2010; Arana-Solares et al. 2011; Marin-Garcia et al. 2018). The adaptability capability facilitates companies’ reaction to structural changes, such as those in supply, demand and business environment (Eckstein et al. 2015; Christopher and Holweg 2017; Feizabadi et al. 2019). Accordingly, SC-Ad consists of two competences regarding SC processes: a) identifying the goals and necessary changes in SC processes to respond to structural changes in the markets; and b) implementing these changes (Alfalla-Luque et al. 2018).

Consequently, SC-Ad is considered crucial for SC’s performance in a complex and turbulent global environment (Tuominen et al. 2004; Ivanov et al. 2010; Garrido-Vega et al. 2023), in which SC must continually adapt strategies and structures (Gibbons et al. 2003; Ivanov et al. 2010), while considering technology and market focuses (Tuominen et al. 2004; Ivanov et al. 2010; Arana-Solares et al. 2011). The importance of SC-Ad is increasing in the current context as it facilitates the reconfiguration of companies’ SC design to respond to structural changes in the markets (Yang et al. 2022). Although the importance and positive effects of SC-Ad on company’s performances have been acknowledged by the literature (e.g.: Lee 2004; Ivanov et al. 2010; Eckstein et al. 2015; Rojo et al. 2016; Yang et al. 2022; Iranmanesh et al. 2023; Daneshvar Kakhki et al. 2023; Marin-Garcia et al. 2023), the research about how to acquire SC-Ad is still limited (Whitten et al. 2012; Eckstein et al. 2015; Alfalla-Luque et al. 2018; Yang et al. 2022).

Regarding SC processes above mentioned, they consist of physical process network structures (from procurement to final delivery to customers) and administrative processes (for designing and managing operations such as physical processes) (Sterman 2000; Ivanov et al. 2010; Abassi and Varga 2022). One significant managerial issue as to SC processes is that companies must adapt those structures and processes to emerging new threats or opportunities timely and appropriately (Skinner 1969; Fisher 1997; Lee 2002, 2004; Ivanov et al. 2010). Although this adaptation is necessary to meet new competitive requirements such as quality, cost and delivery (Lee 2002), such changes have been sometimes considered as a serious managerial challenge because of the inflexibility of SC processes including manufacturing processes, which comes from the consideration of an enormous sunk cost and an immediate loss of efficiency under situations involving the shift (Skinner 1969; Hayes et al. 1988; De Meyer et al. 1989). This inflexibility of existing SC processes sometimes causes a companies’ bias towards exploitative focuses (for current performance), and it is important to prevent companies from having such short-term focus because it could interfere the explorative activities (explorative focus for future performances) such as those related to the adaptation to the aforementioned structural market and competitive changes (Brenner and Tushman 2003).

This is important for companies that wish long time prosperity, but the inflexibility of SC processes (Skinner 1969; Hayes et al. 1988; De Meyer et al. 1989), which gives constraints on timely strategic changes could be a significant barrier for the appropriate balance between these two focuses, which is not yet operationally defined. Those factors such as the cost limitations (Boumgarden et al. 2012; Parida et al. 2016), the tensions between explorative and explorative focuses (He and Wong 2004; Van Looy et al. 2005; Hu and Chen 2016) and the dominant competitive focuses in markets like the topmost importance of innovativeness (Luger et al. 2018; Clauss et al. 2021) make the balancing complex and difficult. Successfully facilitating the steering of switchbacks between the mentioned exploitative and explorative activities (Levinthal 1997), we assume, requires the sufficient competence of mobilizing SC processes in terms of timing and scale with clear sense of future directions.

Despite the strategic importance of enhancing SC-Ad by resolving this inflexibility issue of SC processes (Skinner 1969; Hayes et al. 1988; De Meyer et al. 1989; Fisher 1997; Lee 2002, 2004; Ivanov et al. 2010), and the mentioned positive effects on performance measures (Skinner 1969; Fisher 1997; Lee 2002, 2004; Ivanov et al. 2010; Martínez Sánchez and Pérez Pérez 2005; Eckstein et al. 2015; Rojo et al. 2016; Wamba et al. 2020; Yang et al. 2022; Iranmanesh et al. 2023; Khan et al. 2023; Daneshvar Kakhki et al. 2023), how to drive SC-Ad has not still been well studied and this study seeks to fill this gap. In this sense, this paper aims to expand knowledge about SC-Ad drivers, because addressing the theoretical foundations of dynamic SC capabilities such as SC-Ad, and especially its antecedents, is still in its infancy. This is an important gap as it indicates that managers do not have guidelines to develop a SC-Ad that would make it easier for them to take advantage of new market opportunities (Aslam et al. 2020).

At this point, it is worth remembering that, in practice, leading companies have often shown appropriate examples of mobilization of SC processes by integrating the characteristics of product/market strategy and SC processes to create competitive advantages in specific phases of market competitions, as some cases in the automobile industry indicate. Some examples that can be cited are Ford (T-model and efficient SC process characterized by lot-size economy and assembly lines) (Tedlow 1988; Bednarek and Parkes 2021), General Motors (Class-based variety of models and SC processes under multi-divisional structures) (Chandler Jr. 1962; Sloan 1990; Tedlow 1988), and Toyota (a wide range of small fuel-efficient cars and the lean SC process) (Ohno 1988; Womack et al. 1990), all of which have been acknowledged as “winners” during specific phases of automobile market development when prestigious leaders supported these mobilizations. These cases also suggest that seeking a fit between the product/market strategy aims such as low price, variety and quality and the working properties of SC processes lead companies to successful SC-Ad with competitive advantage. Therefore, it is hoped that investigating how to develop this fit will provide us with important clues to obtain a higher SC-Ad.

Based on the above, this study seeks to propose drivers for the mobilization of SC processes to implement an effective SC-Ad through securing the competitive fit between the product/market strategy focus and the working properties of SC processes, which is a contribution to the existing literature. It is also important to consider that a successfully established effective fit may turn out to be not effective as competitive situations change, making it necessary to change to a new fit as the cases in the automobile industry previously mentioned which focused on the shift from the lot-size economy focused to (the Ford case), then to the variety focused (the General Motors case) and to the lean focused (the Toyota case) exemplified. Consequently, the objective of this study is to find and propose appropriate drivers of SC-Ad that secure the fit between the product/market strategy focuses and the SC processes over time (embracing the mobilization of the strategic aims and SC processes).

To solve this issue, it is important to recall again that SC processes consist of physical process network structures and administrative processes (Sterman 2000; Ivanov et al. 2010; Abassi and Varga 2022), and that to mobilize SC processes, that is, to design, construct, and operate such a network, it is necessary to have the knowledge required to understand what determines the network’s performance given anticipated or planned demand patterns. Without these knowledge drivers, the barriers that generate the inflexibility of SC processes would remain and prevent companies from getting a higher SC-Ad. Regarding this matter, research by Morita et al. (2015, 2018) provides an interesting reference framework for this knowledge. Said authors introduce the concept of absolute SC orientation strategy (ASCOS) and analyzes it in conjunction with the new product development competence (PDC). PDC is related to the SC-Ad competency of determining the goals and requirements of SC processes, and ASCOS is related to the SC-Ad competency of implementing these changes, that is, of configuring and operating the necessary SC processes. Morita et al.’s (2015, 2018) research results show that high levels of ASCOS and PDC lead to high competencies in both existing and new product strength. Therefore, they can be considered potential drivers of SC-Ad in the abovementioned sense. We assume that this approach is expected to contribute to improving company competitiveness overtime by reducing the uncertainty around the feasibility of steering the company’s explorative and exploitative activities by means of ASCOS and PDC, which secure the fit between the product/market strategy and the SC processes over time, so as to get the necessary SC-Ad to adapt to anticipated changes.

The present section is followed by the theoretical background of this research and the hypotheses development. Next, we set out the analytical framework, the measurement of the factors involved, and the analysis of the results. The final section of this study offers the discussion and conclusions.

2 Theoretical background and research hypotheses

Thus far, we have showed that the inflexibility of SC processes makes it difficult to get SC-Ad and then to implement strategic changes of companies, but that this can be overcome by securing a fit that integrates the competences of product/market strategy (strategic focus) and SC processes (SC competence) over time. It was then proposed that the above issue should be addressed by securing this fit through appropriate drivers of SC-Ad in order to enable the successful response to environmental changes, and that absolute SC orientation strategy (ASCOS) in conjunction with the new product development competence (PDC) (Morita et al.’s (2015, 2018)) can be considered potential drivers of SC-Ad in the abovementioned sense. The present section develops the theoretical framework related to these issues and ends with the proposal of the corresponding hypotheses.

The issue of SC process inflexibility, i.e., the issue as to how to improve the flexibility of SC processes including manufacturing is an important problem for many companies seeking satisfactory long-term performance as it impedes timely adaptation to new competitive situations (Skinner 1969; Hayes and Wheelwright 1984; De Meyer et al. 1989; Brenner and Tushman 2003; Winkler 2009). The need for flexible SC processes stems from the view that companies’ strategic focuses need to adapt the firms’ SC processes to new competitive requirements such as quality, on-time delivery, and competitive cost (Fisher 1997; Lee 2002, 2004; Defee and Stank 2005; Selldin and Olhager. 2007; Flynn et al. 2010; Wagner et al. 2012; Prajogo et al. 2018; Sabri 2019) depending on their strategic focuses, as the concepts of generic strategies (Porter 1981) and product/market strategies exemplify (Ansoff 1957). This research assumes that due to SC process inflexibility, many companies struggling to develop a high SC-Ad capability find it difficult to change existing SC process configurations to adapt to new competitive situations.

On the other hand, the fit between competitive requirements (such as the above mentioned) in companies’ markets and their supply process competences to meet these competitive requirements (even in changing environment) is considered to be one of the essential conditions that must be met to sustain high performance (Fisher 1997; Lee 2002, 2004; Defee and Stank 2005; Selldin and Olhager 2007; Flynn et al. 2010; Wagner et al. 2012; Prajogo et al. 2018; Sabri 2019). In this sense, this study assumes that securing this fit (under any changing competitive circumstances) between designed new values that are desirably innovative (e.g., new business or product introductions or new markets through expanded globalization) and the necessary SC process competences presupposes the competence of SC processes to be flexible to adjust to the new requirements, which is necessary for achieving a high SC-Ad.

In this line, this paper focuses on enablers which secure the above-mentioned competitive fit over time to ensure a SC-Ad that responds to emerging competitive changes. Regarding the mentioned issues, if the competences of SC-Ad previously defined in this study (i.e.: specifying the new goals and requirements to be met by SC processes to respond to structural changes in the markets and to implement these changes (Alfalla-Luque et al. 2018)) are strong, they will reduce the inflexibility of SC processes and improve SC-Ad by redefining the fit between designed values and SC processes. Therefore, SC-Ad would give directions and would show desirable changes for a new fit between the company’s strategic focuses and its SC processes while focusing on strengthening this fit competency. Therefore, this research focuses on proposing drivers that strengthen the two aforementioned SC-Ad’s competencies and hypothesizes that companies should be competitive in both.

Morita et al. (2015, 2018)’ works provide a reference framework for these drivers. On the one hand, the above-described first SC-Ad competence (“specifying the goals and requirements to be met by SC processes to respond to structural changes in the markets”) could be considered to be driven by the product development competence (PDC) proposed by the authors, defined as the integration of wisdom for designing and developing new products or services, which involves suppliers, customers, and functional departments such as manufacturing and marketing (Morita et al. 2018). In this sense, PDC is used in this paper to stand for the most representative explorative competence of new value design and development as well as improvements to existing products, and it is conceptualized as the integration of multifunctional explorative competencies. These include the following 4 dimensions, validated in the different rounds of the survey of the High Performance Manufacturing Project (HPM) (about HPM, see Schroeder and Flynn 2001) and used in (Morita et al. 2018): Customer involvement in new product development (NPD), manufacturing involvement in NPD, supplier involvement in NPD and front-end loading in NPD.

On the other hand, Morita et al (2015, 2018)’ proposed the absolute SC orientation strategy (ASCOS), which is related to the second SC-Ad competence (“to implement the required changes”) by the design and operation of SC structures and processes to respond to demand patterns. ASCOS is defined as a measure that contains strengths in four aspects: lead time, just-in-time control, quality conformance, and demand stability, which, together, are all functionally important for any SC process to deliver designed values to markets in terms of efficiency (cost and time) and effectiveness (for customers) (Morita et al. 2015, 2018). Therefore, when a company is ASCOS-oriented, it consistently focuses on these operating process factors and makes constant efforts to improve all four. The four mentioned components of ASCOS are fundamental factors that determine the potential performance of SC processes, which consist of linkages between activities in a network structure whose maneuvering competences are effectively and appropriately exploited in any set of products/markets (Morita et al. 2018). In other words, the capability to maneuver in these ASCOS’s four aspects is expected to be transferable and applied to the design, construction, and operation of SC processes to meet the anticipated competitive requirements of newly targeted products or markets detected thanks to an appropriate PDC competence. In this sense, ASCOS is regarded here as the capability to design and implement any necessary operational activities to meet new competitive requirements. Therefore, if sufficiently high, this capability is expected to reduce the tension associated with the proposed necessary explorative initiatives. To a certain extent, this competence has functional meanings similar to those of the operational absorptive capacity (Patel et al. 2012; Rojo et al. 2018) and organizational nurturing of organizational learning (García-Morales et al. 2008; Rojo et al. 2018) but its construct is more specifically defined as the four mentioned operational focuses that, technically, determine potentially flexible SC process competences.

Summarizing, when designing and developing product and service values, PDC’s superiority is expected to correctly evaluate the existing strengths and weaknesses of current products and configure future products with a high probability of success. On the other hand, ASCOS competence diminishes SC processes’ inflexibility because it facilitates to design and operate SC structures and processes to respond to demand patterns. For example, a desired reduction in time delays could be improved by ASCOS’ lead time reduction focus. Securing information availability such as on-hand inventory level and reliable demand estimation is supported by ASCOS’ just-in-time control, quality conformance, and demand stability focuses. Therefore, PDC and ASCOS are expected to underlie the necessary dynamic adaptation process competence. Thus, due to the above, PDC and ASCOS are hypothesized to act as drivers of SC-Ad, and Hypothesis 1 is formulated as:

Hypothesis 1: ASCOS and PDC are drivers of the SC-Ad.

As noted by Morita et al. (2018), in general, companies tend to be more aggressive towards new product development activities than to SC activities, and this generates a conflict between the long- and short-term visions. An attempt at improvement of the PDC type is explorative focused while the ASCOS type is considered to be exploitative-focused. Regarding this matter, it is important to stress that when a company focuses mainly on exploration it risks building tomorrow’s business at the cost of today’s, while focusing on exploitation it risks losing its long-term vision (Birkinshaw and Gibson 2004). It is, therefore, essential to find an appropriate balance of focuses between the two (Birkinshaw and Gibson 2004; Kristal et al. 2010; Feizabadi and Alibakhshi 2022), and easing the tension between these two focuses is a key strategic challenge (He and Wong 2004; Nieto-Rodriguez 2016). Regarding this matter, it is assumed here that, when ASCOS capability is nurtured in companies, it increases SC processes’ flexibility as it lowers organizational barriers to renewing or rebuilding processes, and also contributes to carrying out an appropriate evaluation of new products or markets in terms of resource requirements and new SC process design. Two focuses, explorative and exploitative, can coexist (Adler et al. 2009; Kortmann et al. 2014; Alcaide-Muñoz and Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez 2017; Gutierrez-Gutierrez and Antony 2020). This can overcome the conflict between exploitative and explorative focuses by a balance in which ASCOS and PDC have both high values, which would lead to SC-Ad’s higher values than other possible combinations of values of these variables (e.g.: high value-low value and low value-high value would be prioritizing one of the focuses, leading to the mentioned conflict between long term and short-term goals. And low value-low value will be against the obtention of an adequate SC-Ad).

Therefore, ASCOS and PDC can (and should) work together in the long-term as adaptations generally must be made due to changes in product/market, SC structures, processes, and ways of operating as a set or package (Morita et al. 2018). In this sense, as previously said, to maintain high performance over time, companies have to secure two types of fit: a) the fit of companies’ strategic goals/aims to actual market and competitive situations (through PDC in this paper), and b) the fit of companies’ SC processes’ competencies to actual competitive requirements (through ASCOS in this research) (Venkatraman and Camillus 1984). Moreover, effective fits are required consecutively over time between their strategic goals and SC processes (Fisher 1997; Lee 2002, 2004; Ivanov et al. 2010; Arana-Solares et al. 2011; Marin-Garcia et al. 2018).

In line with the above comments, this study hypothesizes that the contribution of ASCOS and PDC to the creation of a more reliable and feasible configuration of SC-Ad is higher when both competences are present and are high in value than would otherwise be the case, and that the trade-off between these two competencies would harm the obtention of a high SC-Ad. This would avoid the conflict between the exploitative and explorative focuses, making it easier for companies to be competent in both kind of activities and, thus, be able to sustain the mentioned fits and companies’ competitiveness in changing competitive situations. As mentioned before, ASCOS and PDC should work in partnership to determine a better SC-Ad, overcoming the conflict of exploitation vs exploration under certain managerial cultures that are capable of generalizing the effectiveness and logic of practices involved in the process management above mentioned (Adler et al. 2009; Kortmann et al. 2014; Alcaide-Muñoz and Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez 2017; Gutierrez-Gutierrez and Antony 2020).

Considering the above comments, we can hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 2: Plants with higher SC-Ad values are characterized by higher values of the ASCOS and PDC competences.

Higher PDC and ASCOS lead to more reliable insights into the feasibility and prospects of proposed changes. Therefore, a competitive set of high ASCOS and high PDC is expected to drive a high SC-Ad. To perform these practices well, companies should be equipped with the above-described constituent competencies of ASCOS and PDC.

Figure 1 summarizes the conceptual research framework.

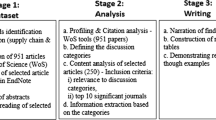

3 Methods

3.1 Sample

A wide multi-country, multi-informant, and multi-sector sample was used to provide highly reliable results. The sample was based on the database of the latest round of the international High-Performance Manufacturing (HPM) Project, which surveyed manufacturing plants (with ≥ 100 employees) in Europe, America, and Asia. Cases with missing values in over 15% of the items included in our study were deleted (Hair et al. 2022). The final sample consisted of 268 plants from 16 developed and emerging countries (Austria, Brazil, China Finland, Germany, Italy, Israel, Japan, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, UK, USA, Vietnam) in three sectors (electronics, machinery, and automotive components), chosen as they are in hotly-contested global competition and desirable managerial practice effects are expected to be identified in such industries. The 268 valid cases had missing values completely at random (MCAR) (little test, sig 0.097). At this point, all the variables with under 5% values missing per item (mean replacement option) (Hair et al. 2021, 2019) were selected in Smart PLS 4.0.8.9 (Ringle et al. 2022). To identify possible sources of heterogeneity in the sample, some control variables have been introduced into the model (country context, industry as dummy and log plant size), allowing the SC-Ad results to be adjusted for possible differences due to the sample. Furthermore, unobserved heterogeneity has been analyzed to verify whether the weights of the measurement model or the paths of the structural model have different values in the data subsamples (Becker et al. 2013; Marin-Garcia and Alfalla-Luque 2019).

3.2 Measures

Our constructs have been adapted from measures defined and validated in previous research. ASCOS and PDC were validated in Morita et al. (2018) and in Morita et al. (2015). All the lower-order composite constructs for ASCOS and PDC (see Table 1) have been measured with reflective indicators. Higher-order composite constructs (ASCOS2_JIT focus, ASCOS3_Quality focus, ASCOS, and PDC, see Table A2 in annex) have been modeled using lower-order construct latent variable scores as formative indicators. SC-Ad was validated in Marin-Garcia et al. (2018) and all the first-order and second-order constructs have been considered formative composite constructs (Table A2 in annex). ASCOS represents the competent culture of SC processes, which is consistently seeking lead time reduction, JIT implementation, demand stability, and quality conformance (Morita et al. 2018). PDC represents the competence of wisdom integration within and beyond organizations for new value development (e.g., product development) (Morita et al. 2018). SC-Ad embraces abilities for changes such as changing SC processes and structures in line with market changes, introducing new technologies (e.g., information technologies), and predicting changes such as those in markets (Marin-Garcia et al. 2018).

The control variables used in this research are in line with those used in previous research (e.g., Dubey et al. 2019; Machuca et al. 2021; Alfalla-Luque et al. 2023): a) plant size (log10), b) industry (dummy variable; reference category = electronics), and c) country context.

Several steps were taken to reduce the risk of common method bias (CMB) (Podsakoff et al. 2003; Schwarz et al. 2017). Different scale anchors were selected for use in the same scale and in different parts of the questionnaire to prevent any priming effects; items were randomly listed in scales to prevent item proximity from generating any response patterns (Marin-Garcia et al. 2018); the questionnaires were responded by two people in each function who had not been informed about what the items were intended to measure (Danese et al. 2019). Informant confidentiality was prioritized during the data collection phase. In addition, Harman’s Single-Factor test (Chin et al. 2013; Schwarz et al. 2017) was applied after collecting the data. The correlation matrix was analyzed using principal component with varimax rotation. The obtained results were robust and valid and indicated that several different factors were present with eigenvalues above 1, which indicated the absence of CMB issues (the presence of a single factor would have indicated CMB).

Using G-Power 3.1, a post hoc power check with 268 plants and R2 = 0.184 (the lowest value in our analysis, corresponding to Ad3 in the 1st-order model) gives a result of 0.99 power with Alpha 5% and 17 predictors. This power value is higher than the recommended cutoff value of 0.8 (Marin-Garcia and Alfalla-Luque 2019).

3.3 Analysis procedure

Measurement and structural models were assessed following the current guidelines for PLS-SEM (Marin-Garcia and Alfalla-Luque 2019; Becker et al. 2023; Sarstedt et al. 2022; Ringle et al. 2023). Mode A was used to calculate the weights of composites with reflective indicators (ASCOS and PDC low-order constructs (LOC)) and Mode B was used for formative indicators (SC-Ad lower order composites, and all 2nd and 3rd higher-order composites) (Hair et al. 2019; Sarstedt et al. 2019). The relative importance of the antecedents to SC-Ad was analyzed using the importance and performance analysis procedure (IPMA) (Hair et al. 2019). An analysis using PLS and PLS-predict was carried out of model in-sample and out-of-sample predictive capacity to show direct relationships of ASCOS and PDC with SC-Ad, respectively (Shmueli et al. 2016; Sharma et al. 2022). This predictive analysis enhances the retrospective character of classic explanatory models and helps to build theories for both explanation and prediction (Liengaard et al. 2021). ANOVA was used to compare ASCOS and PDC in plant groups with different SC-Ad values.

4 Results

The figures that represent 1st LOC (Fig. S1), 2nd HOC (Fig. S2) models and the full research model (Fig. S3) and some tables that complement the analyses can be accessed in the online supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7813833). The items used in the questionnaire and their descriptive statistics are given in Table A1 in the annex.

4.1 Measurement model

The constructs in this research clearly meet the established criteria of internal reliability. Regarding reflective LOCs (see Table 1), the established cut-off values for composite reliability (CR > 0.7) and average variance extracted (AVE > 0.5) are met (Marin-Garcia and Alfalla-Luque 2019; Sarstedt et al. 2022). Regarding Cronbach’s alpha, only one construct has a value below the cut-off value (0.626) but it is, nonetheless, very close to 0.7. It also shows high composite reliability (0.801) and AVE (0.574), which are the most relevant parameters. In addition, it belongs to a formative construct (ASCOS) and this dimension (1st-order construct-demand stability) is a basic part of ASCOS’s conceptual composition (as demonstrated in Morita et al. (2015, 2018). Therefore, it should be left in the model (Hair et al. 2019).

Fornell-Larcker and Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) have been used to test the Discriminant Validity of reflective constructs (Marin-Garcia and Alfalla-Luque 2019; Sarstedt et al. 2022). Both criteria show global satisfactory results (see Table S1 in online supplementary material). Although “Feedback to employees on quality” and “Quality training” do not meet discriminant validity individually (0.777, higher than the diagonal value (0.767)), they should be considered sub-dimensions of a formative HOC with a VIF value lower than the established cut-off value of 3 (see Table S2 in online supplementary material). In addition, their significance means that they are an essential part of their construct and, so, should be left in the model (Hair et al. 2019). In addition, when the HOC order-2 constructs are evaluated (Table A2 in annex), the corresponding loadings and weights show that this is not a problem and does not negatively affect the proposed model.

Regarding the formative constructs, all outer VIF values (see Table S2 in online supplementary material) are lower than the established cut-off value of 3 (Marin-Garcia and Alfalla-Luque 2019; Sarstedt et al. 2022). Also, all weights are significant except two (see Table A2 in annex). However, both have loadings above 0.5 and represent relevant aspects of their construct, so should be retained in the model (Marin-Garcia and Alfalla-Luque 2019; Sarstedt et al. 2022).

4.2 Structural model

The results of the structural model analysis for the third-order composites are presented in Table 2 and Fig. 2. They show that the ASCOS and PDC paths on SC-Ad are both significant, with no overlap between the confidence intervals (0.499 to 0.674 for ASCOS; 0.017 to 0.185 for PDC). In addition, the mean value of the coefficient of determination (R2) is 0.406, i.e., between the 0.344 and 0.509 confidence intervals. This indicates that the two variables (ASCOS and PDC) jointly explain a moderately high percentage of the variance, which is a sign of the model’s adequate predictive power (in-sample prediction). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is confirmed.

Further, as a set, the control variables can be considered not to exert any significant influence. The only significant control variable is the automotive sector in the industry control variable, which has a negative path (indicating that automotive sector firms present less SC-Ad (mean = 3.7) than electronics sector firms (mean = 3.9)). Despite being significant, this difference is almost certainly not relevant given that SC-Ad is in the mid-to-high part of the scale used in both sectors. Furthermore, the existence of a possible unobserved heterogeneity has been analyzed through solutions of 1 to 5 groups with finite mixture partial least squares (FIMIX) (Becker et al. 2013; Marin-Garcia and Alfalla-Luque 2019). The results seem to reinforce that a heterogeneity problem is not a real issue in the sample since they support that the solution of a single group can be considered to represent the results obtained.

The results show that ASCOS has a greater influence on SC-Ad than PDC (see Table 2 and Fig. 2). As Table 3 shows, this is mainly due to the significantly more intense relationship of the ASCOS JIT focus with SC-Ad (0.444). Nonetheless, two of the other ASCOS dimensions (ASCOS3_Quality focus, and ASCOS1_Lead time focus) also contribute to this higher influence (0.224 and 0.166, respectively).

The IPMA analysis (Hair et al. 2019) based on Table 3 (second and third columns) and presented in Fig. 3, also indicates that the influence of ASCOS on SC-Ad is, as already stated, is greater than that of PDC. This is, therefore, the construct that contains the most important levers of SC-Ad. It can also be stated that almost all the ASCOS levers are deployed between 63%-71% of the maximum deployment level, so there is still room for improvement. In this case, ASCOS4_Demand stability focus (the least deployed lever (55% of maximum capacity)) is the lever that least affects the development of SC-Ad. That said, the second least-deployed lever, ASCOS2_JIT focus (63.77%), is the LOC with the highest effect on SC-Ad, which indicates that it is the best candidate to use for leveraging SC-Ad in the plants of our sample.

Finally, it is important to comment that the negative sign in the weight of ASCOS 4 (Table 4) should not be interpreted as an issue as it is due to a "negative or net suppression" effect. This is common when several correlated variables are used in the same model, as is the case here. The tricky issue, in this case, is that although all the variables are positively related to SC-Ad (see latent variable correlations in the 2nd-order HOC model in Table S3 in online supplementary material), a negative value can be observed in the path. The reason for this is well-documented in mediation analysis (Ato and Vallejo 2011; Conger 2016; Krus and Wilkinson 1986) and it is explained by the relative "impact" of the predictors on the dependent variable. The predictor that is least correlated with the dependent variable (ASCOS 4, in this case) is used to “compensate” the “inflated” paths of the other predictors.

The model’s out-of-sample predictive validity was measured using PLS-predict (see Table 4), which allows to empirically compare out-of-sample predictive power (Shmueli et al. 2019; Hair et al. 2022). RMSE is the root mean square error, MAE is the mean absolute error, that is, the average absolute difference between the predictions and the actual observations, with all individual differences having equal weight. RMSE results show that all the indicators and two of the SC-Ad latent variable scores (Ad1 and Ad3) are better predicted with PLS than with simple linear regression (the difference between PLS-LM results is negative). Moreover, taking SC-Ad globally, the PLS model outperforms the linear regression model. In addition, the CVPAT average loss value is lower for PLS-SEM than for the linear model. This indicates that the model possesses good out-of-sample predictive capability, which reinforces the generalization of the results, i.e., the results can be extrapolated to different samples of the same population.

Table 5 shows the ANOVA comparison of the ASCOS and PDC levels of three groups of plants delimited by two SC-Ad cut-off values (µ + 0.5σ) and (µ—0.5σ). The results show that the top SC-Ad group of plants have ASCOS and PDC values significantly higher than those of the other two groups. This suggests that higher SC-Ad plants are characterized by higher ASCOS and PDC competences than those of the other SC-Ad groups as previously hypothesized. Besides, ANOVA has been used to compare the SC-Ad levels of two groups of plants delimited by ASCOS or PDC two cut-off values for high (µ + 0.5σ) and low (µ—0.5σ). The results show (see Table 6) that the mean of SC-Ad is significantly higher in the group of plants with high ASCOS and high PDC than in the in the plants with Low ASCOS and Low PDC. Besides, although the size of the samples of the groups of High ASCOS-Low PDC (11 plants) and Low ASCOS- High PDC (9 plants) are too little to allow comparison tests with the other groups with a robust significance, it should be indicated that the means show a decreasing tendence between the 4 groups when we move from the top group to the lowest one (High-High (4.197658) – High-Low (4.077086)- Low–High (3.616623)- Low-Low (3.311186).

Therefore, the ANOVA results suggest that plants reach their SC-Ad highest values when ASCOS and PDC are working together with high values. Overall, it can be said that Hypothesis 2 seems to be supported. However, it would be advisable to reinforce this conclusion by using larger samples of the high-low and low–high groups, which would allow a complete comparison of the four groups considered.

5 Discussion, implications, and concluding remarks

This study responds to the call for more empirical research focusing on how to build SC-Ad (Whitten et al. 2012; Eckstein et al. 2015; Alfalla-Luque et al. 2018; Aslam et al. 2020; Yang et al. 2022; Garrido-Vega et al. 2023; Marin-Garcia et al 2023). It is an urgent need to facilitate SCs the way to address in a more proactive way the new challenges coming from the increasing turbulence and rapid changes of the current companies’ global context. For this it is necessary that SC could be easily redesigned and reconfigured to successfully address structural changes (Feizabadi and Alibakhshi 2022). As stated by Aslam et al. (2020, p. 436), “the literature on the theoretical underpinnings of dynamic SC capabilities, in particular its antecedents, is still in the nascent stages”, and this is the case of SC-Ad. In this sense, this study contributes to the knowledge about key antecedents of the SC-Ad capability that facilitate companies’ adaptation of strategies, technologies and products to the structural market changes. This is done by providing evidences about effective new drivers that have not been analyzed to date (ASCOS and PDC) as it is shown in a literature review (Feizabadi et al. 2019), which shows that previous research has mainly focused on other kind of antecedents (e.g.: visibility, relationships, process integration…).

By proposing ASCOS and PDC as drivers of SC-Ad this research contributes to literature on the topic in a triple perspective. First, it develops/complements the framework established by Morita et al. (2015, 2018). Second, it contributes to SC-Ad research analyzing ASCOS and PDC as SC-Ad antecedents, which has not been done until now. The results suggest that ASCOS and PDC are drivers of SC-Ad, and that the plants with highest SC-Ad values are those with the higher competence levels of ASCOS and PDC. Finally, in an indirect way, this research also adds some new light on the topic of ambidextrous management (AM) as the SC-Ad’s drivers ASCOS and PDC also appear to facilitate AM. These contributions are commented below.

Higher SC-Ad means higher readiness to adapt SC processes to achieve new strategic goals and aims. This requires an organizational design allowing to change SC processes and structure in line with market changes as well as to introduce new technologies in processes, products and information systems based on the detection of technological cycles. Also, a medium and long-term market knowledge to detect trends and possible medium and long-term changes (Alfalla-Luque et al. 2018).

In this sense, ASCOS facilitates an organizational design like the one mentioned through its 4 dimensions. The inflexibility of operational processes, pointed as a significant barrier for strategic behaviors of many companies (Skinner 1969; Hayes and Wheelwright 1984; De Meyer et al. 1989; Brenner and Tushman 2003), implies that their drivers of SC-Ad are not adequate. This study’s results contribute to solve this issue by suggesting that ASCOS can be considered an effective driver of SC-Ad through the constant improvement of its four key facets (lead time, just-in-time control, quality conformance, and demand stability) to design, upgrade, and adjust SC processes for coming competition over time. Therefore, a high ASCOS value means greater power to fight against the mentioned inflexibility barrier. Moreover, low SC process competence (due to low ASCOS) induces greater adherence to existing processes and stronger resistance to the changes in processes, which are needed for more innovative product introduction or new product/market strategies such as large-scale globalization than would otherwise be the case. So, in the mentioned case, low ASCOS competence triggers attitudes averse to changing existing processes, which makes it difficult to enact SC-Ad. The reason may be that such strategic innovative changes tend to require significant structural changes in SC processes and that the new levels required will be difficult for companies with low ASCOS competence levels to accomplish.

On the other hand, designing appropriate new specifications for next SC processes requires good information feedback on markets, customers, competitors, etc., and thus PDC’s competence level should be on a par with that of ASCOS. PDC helps to detect trends and possible medium and long-term market changes through the involvement of customers, suppliers, manufacturing, and front-end loading in new product development. This has been confirmed by the ANOVA results, which show that the highest values of SC-Ad are attained by plants with the highest values of both ASCOS and PDC, which jointly contribute to SC-Ad. These results seem to show that although PDC’s effect on SC-Ad is weaker than that of ASCOS’, this should not be taken as a suggestion that PDC should not be considered as it allows to explain a higher deployment of the SC-Ad capability. In this sense, high SC-Ad requires high values of ASCOS and PDC competences together to secure fits of satisfactory performances between strategic goals/aims and properties of SC processes over time. Finally, the reduction in the uncertainty around the expected performance of explorative initiatives is enabled by refining the estimation of expected performance. Our analyses suggest that the estimation based on the best combination of new values (related to PDC) and SC processes (related to ASCOS) is possibly associated with the enhancement of the quality of the estimates and leads to better decision-making whatever the final decision, be it affirmative or negative.

The bottom line of this study is to show the importance of strengthening physical value delivery processes. The satisfactory performance of explorative activities such as new product developments is reaped together with competent physical value delivery processes, i.e., SC processes, over product life cycles (Morita et al. 2018). The inflexibility that slows down or sometimes even prevents the achievement of SC-Ad is alleviated by the SC process competence, which is organizationally shared and improved based on the normative ASCOS principles of SC processes and successfully adapts itself to changing competitive situations over time.

One important factor that should be stressed in this section is that our results support the idea that, to progress toward high SC-Ad, which sustains long-run adaptation of companies with satisfactory performances, companies should be “normatively envisioned” and focused on maintaining high levels of both the ASCOS and PDC competences. However, this would require a change in the mentality of many organizations that are not normatively envisioned, as can be observed in our results, which show that approximately 28% of the plants in the sample present low ASCOS and PDC values, with approximately 43% presenting a low value in at least one of the two. This leads to a lower value of SC-Ad that most likely slows down or even prevents the achievement of SC-Ad. In turn, no or little SC-Ad coming from low values of ASCOS and PDC implies that it is almost impossible for these plants to completely eliminate the uncertainties attached to any explorative initiatives if there is no change in their managerial mentality that might result in a new focus with a rational approach to this issue and an increase in both the potentiality and the feasibility of the initiatives. This fact can be considered an important managerial implication.

Continuing with practical implications, this research is valuable for managers because SC-Ad capability is difficult to develop in practice as it needs to continuously assess customer needs, to identify new markets and be able to generate flexible designs (Whitten et al. 2012). Moreover, it needs to reconfigure processes with SC partners, which is difficult and risky because any reconfiguration implies new operational uncertainties (Chan and Chan 2010; Bode et al. 2011). This study helps to overcome this problem by identifying how to build SC-Ad through effective drivers, which help managers to allocate resources in order to facilitate the adjustment of SC partners to match new markets requirements in the long term (Aslam et al. 2020).

Obtaining further implications for managers requires digging deeper into the analysis of ASCOS as it is the most influential SC-Ad driver; it should be recalled that the effectiveness of the JIT focus on SC-Ad is the largest one (total effect of 0.444). Therefore, it is the most powerful sub-lever that must be increased in our sample of companies to improve SC-Ad, especially if it is considered that its deployment level only stands at 63.776% of its maximum capacity (see Table 3 and Fig. 3). The measure of JIT is important in the sense that ASCOS assumes the adoption of JIT as a rule of controlling flows through SC processes. In other words, the degree of understanding JIT determines the degree of understanding of meaningfulness of ASCOS. Furthermore, it is important to consider that the JIT competence is generally supported by the other three ASCOS’s focuses (short lead time, high-quality conformance, smoothed production volume (stable demand)) and even by other resources, including trained human resources (Ohno 1988; Sakakibara et al. 2001; Singh and Singh 2013). Thus, the other three sub-competences should not be neglected because, as pointed above, in practice, they contribute to the performance level of JIT and therefore companies should focus on the improvement of all ASCOS components. In our sample, the relevance of the JIT focus is followed by Quality focus (0.224) and Lead time focus (0.166) and, although lower, both can be considered major SC-Ad sub-levers with room for improvement (71.442% and 66.994% deployment levels, respectively). This information about the most influential levers deployed by the plants in our sample is important for managers seeking to enhance the competence of initiating SC-Ad. As these comments refer to the aggregate sample, this analysis should be nuanced for company actions with due consideration of the conditions and circumstances of individual plants. In other respects, as mentioned above, although PDC’s effect on SC-Ad is weaker than that of ASCOS’, it should not be neglected as when having a high value together with ASCOS it allows a better balance of exploitative and explorative activities and facilitates a higher deployment of the SC-Ad capability.

At this point it is maybe worth highlighting another contribution of this research, which comes from the connection of this investigation with that of ambidextrous management (AM), which aims to secure companies’ “survival and prosperity” (March 1991) by keeping an appropriate balance of resource commitments between future-focused explorative and present-focused exploitative activities. In the same sense, many authors state that AM seeks to find an appropriate balance between exploitation (leveraging of competence of daily operations) and exploration (leveraging of competence of innovative and adaptive response to environmental structural changes) focuses (Levinthal and March 1993; Birkinshaw and Gibson 2004; He and Wong 2004; Junni et al. 2013; Nieto-Rodriguez 2014; Karrer and Fleck 2015), and that easing the tension between these two focuses is at the heart of company survival and prosperity (March 1991) as well as the sine qua non of organizational ambidexterity (O'Reilly and Tushman 2004). Although AM has become one of the most important focuses in the field of management research and practice as many authors suggested as above, some key questions have still not been sufficiently addressed (O’Reilly and Tushman 2004; Ogrean and Herciu 2019; Binci et al. 2020; Pertusa-Ortega et al. 2021; Kafetzopoulos 2021). For example, questions continue around how to successfully implement AM and, despite its mentioned relevance, this remains an important research gap since, as the above studies point out, it is not still clear how to best achieve AM. One of the main barriers is the inflexibility of SC processes stemming from huge sunk cost and risks or difficulties attached to the change of existing SC processes (March 1991; Duarte et al. 2017), which makes difficult to initiate the necessary shifts between exploitative and explorative activities to find a balance allowing an AM to sustain competitiveness under changing competitive situations (He and Wong 2004; Van Looy et al. 2005; Boumgarden et al. 2012; Hu and Chen 2016; Parida et al. 2016; Luger et al. 2018; Clauss et al. 2021).

Related to this gap in the AM literature, we could say that our results and findings give some new light to the mentioned issue, as the SC-Ad’s drivers ASCOS and PDC, which enable a higher SC-Ad by reducing the inflexibility of SC processes, facilitate the appropriate shifts between exploitative and explorative activities over time and then also AM. In this sense, we could say that although in an indirect way, this research also provides some new insight on this topic, where there is a lack of research (O’Reilly and Tushman 2004; Asif 2017; Ogrean and Herciu 2019; Pertusa-Ortega et al. 2021; Kafetzopoulos 2021).

Regarding the reliability of the results, it is important to note that reliability of this research’s results is improved by the use of a wide multi-country, multi-informant, and multi-sector sample (in which we have not found a problem of heterogeneity), in contrast with studies that use a sample at the national or regional level, and/or of a single sector, and/or with single respondents. This is beneficial as it improves the generalizability of the results. This has been reinforced by the use of PLSPredict, which has confirmed that the model has a good out-of-sample predictive capability that enables the results to be extrapolated to other samples of the same population. On the managerial side, where it is important to find generalizable models that can be useful for business or produce predictive power (Ruddock 2017), this enables managerial decisions that will be more likely to work in other settings (Chin et al. 2020). Besides, the effects of the control variables (plant size, country, and industry) are seen to be non-significant, which strengthens the obtained results.

6 Limitations and further research

This research is not free of limitations. However, these can indicate some lines of possible future research. First, the database only comprises three industries in a limited number of countries. Despite the above-mentioned adequate generalizability of the results, these must be interpreted in the context of these sectors and countries. Nonetheless, the control variables did not have any significant influence on the results and the complementary heterogeneity test did not show any issue on this matter, which is a sign of robustness. In any case, it would be advisable to extend this research to other samples from different sectors and countries. Another limitation is the use of cross-sectional analysis, which is commonly used in many studies but does not allow to observe change/reactions to change in practice. The concept of “adaptation” requires us to look at companies’ behaviors including data over time. Further research would be improved by using longitudinal analyses desirably based on time series data of more than a few product life cycles, which would enable to observe the evolution of the variables and their relationships. Hopefully, the next round of the HPM project will allow such research to be done.

A last important factor to be considered in further research is the role of managerial leadership, especially, top leadership as a facilitator or initiator. There are many studies on the positive role played by this factor regarding leaning toward explorative initiatives (Jansen et al. 2009; Kafetzopoulos 2021). In this sense, Section 1 referred to the three cases of Ford, GM, and Toyota (quoted as examples of a successful fit between product values and SC processes (PDC and ASCOS)), mentioning their three prodigious top leaders, Henry Ford, Alfred P. Sloan Jr., and Kiichiro Toyoda. It is highly likely that these leaders triggered and drove these successful watershed shifts in mentality with little certainty but with great belief in the theoretical insights that this study seeks to emphasize. For example, Mr. Toyoda said that the best way to make a car is by having a required part arrive at the very moment that a worker needs to assemble it (Ohno 1988). This was the birth of the JIT system and Toyota’s worldwide success. It would, therefore, not seem to be by chance that this work has revealed a focus on JIT to be the most important ASCOS lever for obtaining higher SC-Ad, which re-confirms Mr. Toyoda’s vision many years later. Moreover, Skinner (1969) observed that most inflexibility issues came from senior managers’ indifference to anything related to processes. The reliability and quality of this assessment are expected to depend onASCOS and PDC competence levels of the companies’ managers, which reflect the maneuverability of the critical factors that determine the performance of their processes. So, to associate the leadership issue with this research implication, we close this paper with two real examples that are provided as supplementary material in line with our results that spark further research (see https://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo.7813833).

References

Abassi M, Varga L (2022) Steering supply chains from a complex systems perspective. Eur J Manag Stud 27(1):5–38. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJMS-04-2021-0030

Adler PS, Brenner M, Brunner DJ, MacDuffie JP, Osono E, Staats BR, Takeuchi H, Tushman ML, Winter SG (2009) Perspectives on the productivity dilemma. J Oper Manag 27:99–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2009.01.004

Alcaide-Muñoz C, Gutierrez-Gutierrez LJ (2017) Six sigma and organisational ambidexterity: a systematic review and conceptual framework. Int J Lean Six Sigma 8:436–456. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLSS-08-2016-0040

Alfalla-Luque R, Machuca JAD, Marin-Garcia JA (2018) Triple-A and competitive advantage in supply chains: empirical research in developed countries. Int J Prod Econ 203:48–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2018.05.020

Alfalla-Luque R, Luján García DE, Marin-Garcia JA (2023) Supply chain agility and performance: evidence from a meta-analysis. Int J Oper Prod Manag 43(10):1587–1633. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-05-2022-0316

Ansoff I (1957) Strategies for diversification. Harv Bus Rev 5:113–124

Arana-Solares I, Machuca JAD, Alfalla-Luque R. (2011) Proposed framework for research in the triple A (agility, adaptability, alignment) in supply chains. In: Flynn B, Morita M and Machuca JAD (ed) Managing global supply chain relationships: Operations, strategies and practices, IGI Global, Hershey, PA, pp 306–321. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-61692-862-9.ch013

Asif M (2017) Exploring the antecedents of ambidexterity: a taxonomic approach. Manag Decision 55:1489–1505. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-12-2016-089

Aslam H, Blome C, Roscoe S, Azhar TM (2020) Determining the antecedents of dynamic supply chain capabilities. Supply Chain Manag 25(4):427–442. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-02-2019-0074

Ato M, Vallejo G (2011) Los efectos de terceras variables en la investigación psicológica. An Psicol 27:550–561

Becker J-M, Rai A, Ringle CM, Völckner F (2013) Discovering unobserved heterogeneity in structural equation models to avert validity threats. MIS Q 37(3):665–694

Becker J-M, Hwa CJ, Ghollamzadeh R, Ringle CM, Starstedt M (2023) PLS-SEM’s most wanted guidance. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 35:321–346. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-04-2022-0474

Bednarek M, Parkes A (2021) Legacy of Fordism and product life cycle management in the modern economy. Manag Prod Eng Rev 12:61–71. https://doi.org/10.24425/mper.2021.13687

Binci D, Belisari B, Appolloni A (2020) BPM and change management: an ambidextrous perspective. Bus Process Manag J 26:1–23. https://doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-06-2018-0158

Birkinshaw J, Gibson C (2004) Building Ambidexterity into an Organisation. MIT Sloan Manag Rev 45:47–55

Bode C, Wagner SM, Petersen KJ, Ellram LM (2011) Understanding responses to supply chain disruptions: insights from information processing and resource dependence perspectives. Acad Manag J 54(4):833–856

Boumgarden P, Nickerson J, Zenger TR (2012) Sailing into the wind: exploring the relationships among ambidexterity, vacillation, and organizational performance. Strateg Manag J 33:587–610. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.1972

Brenner MK, Tushman ML (2003) Exploitation, exploration, and process management: the productivity dilemma revisited. Acad Manage Rev 28:238–256. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2003.9416096

Chan HK, Chan FTS (2010) Comparative study of adaptability and flexibility in distributed manufacturing supply chains. Decis Support Syst 48(2):331–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2009.09.001

Chandler AD Jr (1962) Strategy and structure: chapters in the history of the American industrial enterprise. MIT Press, Cambridge

Chin W, Cheah J-H, Liu Y, Ting H, Lim X-J, Cham T-H (2020) Demystifying the role of causal-predictive modeling using partial least squares structural equation modeling in information systems research. Ind Manag Data Syst 120:2161–2209. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-10-2019-0529

Chin WW, Thatcher JB, Wright RT, Steel D (2013) Controlling for Common Method Variance in PLS Analysis: The Measured Latent Marker Variable Approach. In: Abdi H et al. (eds) New Perspectives in Partial Least Squares and Related Methods, Springer, New York, pp 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-8283-3_16

Christopher M, Holweg M (2017) Supply chain 2.0 revisited: a framework for managing volatility-induced risk in the supply chain. Int J Phys Distrib Logist Manag 47:2–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-09-2016-0245

Clauss T, Kraus S, Kallinger FL, Bicane PM, Bremd A, Kailer N (2021) Organizational ambidexterity and competitive advantage: the role of strategic agility in the exploration-exploitation paradox. J Innov Knowl 6:203–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2020.07.003

Conger AJ (2016) A revised definition for suppressor variables: a guide to their identification and interpretation. Educ Psychol Meas 34:35–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164474033400105

Danese P, Lion A, Vinelli A (2019) Drivers and enablers of supplier sustainability practices: a survey-based analysis. Int J Prod Res 57(7):2034–2056. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2018.1519265

Daneshvar Kakhki M, Rea A, Deiranlou M (2023) Data analytics dynamic capabilities for Triple-A supply chains. Ind Manag Data Syst 123(2):534–555. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-03-2022-0167

De Meyer A, Nakane J, Miller JG, Ferdows K (1989) Flexibility: the next competitive battle the manufacturing futures survey. Strateg Manag J 10:135–144. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250100204

Defee C, Stank TP (2005) Applying the strategy-structure-performance paradigm to the supply chain environment. Int J Logist 16:28–50. https://doi.org/10.1108/09574090510617349

Duarte FAK, Madeira J, Moura C, Carvalho J, Moreira JRM (2017) Barriers to innovation activities as determinants of ongoing activities or abandoned. Int J Innov Sci Eng Technol 9:244–264. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJIS-01-2017-0006

Dubey R, Gunasekaran A, Childe SJ (2019) Big data analytics capability in supply chain agility: the moderating effect of organizational flexibility. Manag Decis 57(8):2092–2112. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-01-2018-0119

Eckstein D, Goellner M, Blome C, Henke M (2015) The performance impact of supply chain agility and supply chain adaptability: the moderating effect of product complexity. Int J Prod Res 53(10):3028–3046. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2014.970707

Feizabadi J, Alibakhshi S (2022) Synergistic effect of cooperation and coordination to enhance the firm’s supply chain adaptability and performance. Benckmark: Int J 29(1):136–171. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-11-2020-0589

Feizabadi J, Maloni M, Gligor DM (2019) Benchmarking the triple-A supply chain: orchestrating agility, adaptability, and alignment. Benckmark: Int J 26(1):271–285. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-03-2018-0059

Fisher ML (1997) What is the right supply chain for your product? Harv Bus Rev 75:105–116

Flynn BB, Huo B, Zhao X (2010) The impact of supply chain integration on performance: a contingency and configuration approach. J Oper Manag 28:58–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2009.06.001

García-Morales VJ, Llorens-Montes FJ, Verdú-Jover AJ (2008) The effects of transformational leadership on organizational performance through knowledge and innovation. Br J Manag 19:299–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2007.00547.x

Garrido-Vega P, Moyano-Fuentes J, Sacristán-Díaz M, Alfalla-Luque R (2023) The role of competitive environment and strategy in the supply chain’s agility, adaptability, and alignment capabilities. Eur J Manag Bus Econ 32(2):133–148. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJMBE-01-2021-0018

Gibbons P, Kennealy R, Lavin G (2003) Adaptability and performance effects of business level strategies: an empirical test. Ir Market Rev 16(2):57–64

Gutierrez-Gutierrez L, Antony J (2020) Continuous improvement initiatives for dynamic capabilities development: a systematic literature review. Int J Lean Six Sigma 11:125–149. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijlss-07-2018-0071

Hair JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M, Danks NP, Ray S (2021) Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R. A Workbook. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80519-7

Hair JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2022) A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

Hair JF, Hult GT, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M, Castillo-Apraiz J, Cepeda-Carrión G, Roldan JL (2019) Manual de Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd edn, Omnia Science. https://doi.org/10.3926/oss.37

Hayes RH, Wheelwright SC (1984) Restoring our competitive edge: competing through manufacturing. John Wiley & Sons, New York

Hayes RH, Wheelwright SC, Clark K (1988) Dynamic manufacturing: creating the learning organization. The Free Press, New York

He Z, Wong P (2004) Exploration vs. Exploitation: an empirical test of the ambidexterity hypothesis. Organ Sci 15:481–494. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1040.0078

Hu B, Chen W (2016) Business model ambidexterity and technological performance: evidence from China. Technol Anal Strateg Manag 28(5):583–600. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2015.1122186

Iranmanesh M, Maroufkhani P, Asadi S, Ghobakhloo M (2023) Effects of supply chain transparency, alignment, adaptability, and agility on blockchain adoption in supply chain among SMEs. Comput Ind Eng 176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2022.108931

Ivanov D, Sokolov B, Kaeschel J (2010) A multi-structural framework for adaptive supply chain planning and operations control with structure dynamics considerations. Eur J Oper Res 200:409–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2009.01.002

Jansen JJP, Tempelaar MP, Van den Bosch FAJ, Volberda HW (2009) Structural differentiation and ambidexterity: the mediating role of integration mechanisms. Organ Sci 20:797–811. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1080.0415

Junni P, Sarala RM, Taras V, Tarba S (2013) Organizational ambidexterity and performance: a meta-analysis. Acad Manag Perspect 27:299–312. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2012.0015

Kafetzopoulos D (2021) Organizational ambidexterity: antecedents, performance and environmental uncertainty. Bus Process Manag J 27:922–940. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308316058

Karrer D, Fleck D (2015) Organizing for ambidexterity: a paradox-based typology of ambidexterity-related organizational states. BAR 12:365–383. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-7692bar2015150029

Khan SAR, Piprani AZ, Yu Z (2023) Supply chain analytics and post-pandemic performance: mediating role of triple-A supply chain strategies. Int J Emerg Mark 18(6):1330–1354. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-11-2021-1744

Kortmann S, Gelhard C, Zimmermann C, Piller FT (2014) Linking strategic flexibility and operational efficiency: the mediating role of ambidextrous operational capabilities. JOM 32:475–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2014.09.007

Kristal MM, Huang X, Roth AV (2010) The effect of an ambidextrous supply chain strategy on combinative competitive capabilities and business performance. JOM 28(5):415–429

Krus DJ (1986) Wilkinson SM (1986) Demonstration of properties of a suppressor variable. Behav Res Meth 18:21–24. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03200988/

Lee H (2002) Aligning supply chain strategy with product uncertainties. Calif Manage Rev 44:105–119. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166135

Lee HL (2004) The Triple-A supply chain. Harv Bus Rev 82:102–112

Levinthal DA (1997) Adaptation on rugged landscape. Manage Sci 43:934–950. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.43.7.934

Levinthal DA, March KG (1993) The myopia of learning. Strateg Manag J 14:95–112. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250141009

Liengaard BD, Sharma PN, Hult GT, Jensen BJ, Started M, Hair J, Ringle C (2021) Prediction: Coveted, yet forsaken? Introducing a cross-validated predictive ability test in partial least squares path modeling. Decis Sci 52:362–392. https://doi.org/10.1111/deci.12445

Luger J, Raisch S, Schimmer M (2018) Dynamic balancing of exploration and exploitation: the contingent benefits of ambidexterity. Organ Sci 29(3):1–22

Machuca JAD, Marin-Garcia JA, Alfalla-Luque R (2021) The country context in Triple-A supply chains: an advanced PLS–SEM research study in emerging vs developed countries. Ind Manag Data Syst 121:228–267. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-09-2020-0536

March JG (1991) Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organ Sci 2:71–87. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2.1.71

Marin-Garcia JA, Alfalla-Luque R (2019) Key issues on Partial Least Squares (PLS) in operations management research: a guide to submissions. J Ind Eng Manag 12(2):219–240. https://doi.org/10.3926/jiem.2944

Marin-Garcia JA, Alfalla-Luque R, Machuca JAD (2018) A Triple-A supply chain measurement model: validation and analysis. Int J Phys Distribution 48:976–994. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-06-2018-0233

Marin-Garcia JA, Machuca JAD, Alfalla-Luque R (2023) In search of a suitable way to deploy Triple-A capabilities through assessment of AAA models' competitive advantage predictive capacity. Int J Phys Distrib Logist Manag 53(7/8):860–885. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-03-2022-0091

Martinez Sánchez A, Pérez Pėrez M (2005) Supply chain flexibility and firm performance: a conceptual model and empirical study in the automotive industry. Int J Oper Prod 25:681–700. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570510605090

Morita M, Machuca JAD, Flynn JE, Peréz de los Ríos JL (2015) Alignning product characteristics and the supply chain process-a normative perspective. Int J Prod Econ 161:228–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2014.09.024

Morita M, Machuca JAD, Pérez Díez de los Ríos JL (2018) Integration of product development capability and supply chain capability: the driver for high performance adaptation. Int J Prod Econ 200:68–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2018.03.016

Nieto-Rodriguez A (2014) Ambidexterity Inc. Bus Strateg Rev 25:34–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8616.2014.01089.x

Nieto-Rodriguez A (2016). The focused organization: How concentrating on a few key initiatives can dramatically improve strategy execution. Routlege, London

O’Reilly CA, Tushman ML (2004) The ambidextrous organization. Harv Bus Rev 82(4):74–81

Ogrean C, Herciu M (2019) Ambidexterity – a new paradigm for organizations facing complexity. Stud Bus Econ 14:145–159. https://doi.org/10.2478/sbe-2019-0050

Ohno T (1988) Toyota production system. Productivity Press, New York. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429273018

Parida V, Oghazi P, Sedergren S (2016) A study of how ICT capabilities can influence dynamic capabilities. J Enterp Inf Manag 29:179–201. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-07-2012-0039

Patel PC, Terjesen S, Li D (2012) Enhancing effects of manufacturing flexibility through operational absorptive capacity and operational ambidexterity. JOM 30:201–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2011.10.004

Pertusa-Ortega EM, Molina-Azorín JF, Tarí J, Pereira-Moliner J, López-Gamero MD (2021) The microfoundations of organizational ambidexterity: a systematic review of individual ambidexterity through a multilevel framework. BRQ 24:355–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/234094442092971

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88(5):879–903

Porter ME (1981) Competitive strategy. The Free Press, New York

Prajogo D, Mena C, Nair A (2018) The fit between supply chain strategies and practices: a contingency approach and comparative analysis. IEEE Trans Eng Manag 65:168–218. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2017.2756982

Ringle CM, Wende S, Becker JM (2022) SmartPLS 4. In. Oststeinbek: SmartPLS GmbH, Available at http://www.smartpls.com

Ringle CM, Sarstedt M, Sinkovics N, Sinkovics RR (2023) A perspective on using partial least squares structural equation modelling in data articles. Data Br 48:109074

Rojo A, Llorens-Montes J, Perez-Arostegui MN (2016) The impact of ambidexterity on supply chain flexibility fit. Int J Supply Chain Manag 21:433–452. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-08-2015-0328

Rojo A, Stevenson M, Llorens-Montes J, Perez-Arostegui MN (2018) Supply chain flexibility in dynamic environments: the enabling role of operational absorptive capacity and organizational learning. Int J Oper 38:636–666. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-08-2016-0450

Ruddock R (2017) Statistical significance: why it often doesn’t mean much to marketers. Accessed 1 Aug 2022

Sabri Y (2019) In pursuit of supply chain fit. Int J Logist 30:821–844. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-03-2018-0068

Sakakibara S, Flynn BB, De Toni A (2001) JIT manufacturing: development of infrastructure linkages. In: Schroeder RG, Flynn BB (eds) High Performance Manufacturing: Global Perspectives. John Wiley & Sons Inc, New York, pp 141–161

Sarstedt M, Hair JF, Cheah J-H, Becker J-M, Ringle CM (2019) How to specify, estimate, and validate higher-order constructs in PLS-SEM. Australas Mark J 27(3):197–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2019.05.003

Sarstedt M, Hair JF, Ringle CM (2022) PLS-SEM: indeed, a silver bullet - Retrospective observations and recent advances. J Mark Theory Pract. https://doi.org/10.1080/10696679.2022.2056488

Schroeder RG, Flynn BB (2001) High performance manufacturing: global Perspectives. John Wiley, New York

Schwarz A, Rizzuto T, Carraher-Wolverton C, Roldán JL, Barrera-Barrera R (2017) Examining the impact and detection of the “Urban Legend” of common method bias. SIGMIS Database 48(1):93–119. https://doi.org/10.1145/3051473.3051479

Selldin E, Olhager J (2007) Linking products with supply chains: testing Fisher’s model. Supply Chain Manag 12:42–51. https://doi.org/10.1108/13598540710724392

Sharma PN, Liengaard BDD, Hair JF, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM (2022) Predictive model assessment and selection in composite-based modeling using PLS-SEM: extensions and guidelines for using CVPAT. Eur J Mark. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-08-2020-0636

Shmueli G, Ray S, Velasquez Estrada JM, Chatla SB (2016) The elephant in the room: predictive performance of PLS models. J Bus Res 69:4552–4564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.03.049

Shmueli G, Sarstedt M, Hair JF, Cheah J-H, Ting H, Vaithilingam S, Ringle CM (2019) Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: guidelines for using PLSpredict. Eur J Mark 53(11):2322–2347. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-02-2019-0189

Singh DK, Singh S (2013) JIT: a strategic tool of inventory management. Int J Eng Res Appl 3:133–136

Skinner W (1969) Manufacturing-Missing Link in Corporate Strategy. Harv Bus Rev 47:36–145

Sloan AP (1990) My years with general motors. Currency, New York

Sterman J (2000) Business dynamics: systems thinking and modeling for a complex world. Irwin McGraw-Hill, New York

Tedlow RS (1988) The struggle for dominance in the automobile market: the early years of Ford and General Motors. BEH 17:49–62

Tuominen M, Rajala A, Möller K (2004) How does adaptability drive firm innovativeness? J Bus Res 57(5):495–506

Van Looy B, Martens T, Debackere K (2005) Organizing for continuous innovation: on the sustainability of ambidextrous organizations. Creat Innov Manag 14(3):208–221. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8691.2005.00341.x

Venkatraman N, Camillus JC (1984) Exploring the concept of "fit" in strategic management. Acad Manage Rev 9:513–525. https://doi.org/10.2307/258291

Wagner SM, Grosse-Ruyken PT, Erhun F (2012) The link between supply chain fit and financial performance of the firm. JOM 30:340–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2012.01.001

Wamba SF, Queiroz MM, Trinchera L (2020) Dynamics between blockchain adoption determinants and supply chain performance: an empirical investigation. Int J Prod Econ 229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2020.107791

Whitten GD, Green KW, Zelbst PJ (2012) Triple-A supply chain performance. Int J Oper Prod Manag 32(1):28–48. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443571211195727

Winkler H (2009) How to improve supply chain flexibility using strategic supply chain networks. Logist Res 1:15–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12159-008-0001-6

Womack JP, Jones DT, Roos D (1990) The machine that changed the world. Free Press, New York

Yang L, Huo B, Gu M (2022) The impact of information sharing on supply chain adaptability and operational performance. Int J Logist Manag 33(2):590–619. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-11-2020-0439

Funding

Funding for open access publishing: Universidad de Sevilla/CBUA. This study has been conducted within the frameworks of the following funded competitive projects: PID2019-105001GB-I00 by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 (Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación- Spain); PY20_01209 (PAIDI 2020- Consejería de Transformación Económica, Industria, Conocimiento y Universidades -Junta de Andalucía); Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, 17K03952, Michiya Morita.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Special issue: This article belongs to the OMR’s Special issue from the 6th World P&OM Conference (Osaka, Japan, August 2024).

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Final note: We confirm that this work is original, and no prior or duplicate publication of any part of this work has been published elsewhere, nor is it currently being considered for publication in any other journal.All the authors have read the manuscript, the requirements for authorship have been met, and we believe that the manuscript represents honest work. Moreover, there are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

ANNEX

ANNEX

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Morita, M., Machuca, J.A.D., Marin-Garcia, J.A. et al. Drivers of supply chain adaptability: insights into mobilizing supply chain processes. A multi-country and multi-sector empirical research. Oper Manag Res (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-024-00474-4