Abstract

This study is the first to document how older adults in East Asian and Western societies spend their time, across four key dimensions of daily life, by respondent’s gender and education level. To do this, we undertook a pioneering effort and harmonized cross-sectional time-use data from East Asian countries (China, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan) with data from the Multinational Time Use Study (Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Italy, The Netherlands, Norway, Spain, United Kingdom, United States; to which we refer as Western countries), collected between 2000 and 2015. Findings from bivariate and multivariate models suggest that daily time budgets of East Asian older adults are different from their counterparts in most Western countries. Specifically, gender gaps in domestic work, leisure, and sleep time were larger in East Asian contexts, than in Western countries. Gender gaps in paid work were larger in China compared to all other regions. Higher levels of educational attainment were associated with less paid work, more leisure, and less sleep time in East Asian countries, while in Western countries they were associated with more paid work, less domestic work, and less sleep. Interestingly, Italy and Spain, two Southern European welfare regimes, shared more similarities with East Asian countries than with other Western countries. We interpret and discuss the implications of these findings for population aging research, and welfare policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Time is one of the most important resources we have, and despite appearing to be equally distributed, social forces shape imbalances and inequalities in how we use time, affecting population health and well-being (Adjei et al., 2017; Blair-Loy et al., 2015; Chatzitheochari & Arber, 2009; Luyster et al., 2012; Ng & Popkin, 2012; Thompson & Dahling, 2019). Documenting time-use inequalities across socio-demographic groups can help address larger societal issues like inequalities in pay, physical and mental health, life expectancy and happiness (Bianchi et al., 2014; Musick et al., 2020; Nomaguchi et al., 2005; Sayer et al., 2009). Previous comparative time-use studies have focused predominantly on working age adults (Hertog et al., 2021; Kan et al., 2011; Sullivan & Gershuny, 2001; Sullivan et al., 2018), and we know little about time-use patterns later in the life-course (for notable exceptions see Adjei & Brand, 2018; Anxo et al. 2011). Given demographic trends in population aging (i.e., the share of older adults is growing compared to younger people; Bloom et al., 2011; He et al., 2016), it is imperative for scholars to study the time-use budgets of older populations. This knowledge will inform policies aiming to provide adequate and sufficient support for their needs. Furthermore, the conventional approach excluding older people from time-use studies inevitably results in a lower coverage of the general population. Moreover, prior work has mainly documented time-use patterns in Western societies (Adjei & Brand, 2018; Anxo et al. 2011; Mattingly & Sayer, 2006), leaving a desert of knowledge about time-use budgets in other geo-cultural contexts like Asian countries, or the Global South (this pattern is changing, however). Finally, because previous work examining linkages between welfare regimes and people’s daily lives has also focused mainly on working adults (Kan et al., 2011), we know little about how older populations fare. These limitations are partly due to lack of, or difficulty in accessing quality time-use data. To help close this gap, this project makes a pioneering effort and harmonizes time-use surveys from four East Asian countries (China, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan) with data from ten Western countries included in the Multinational Time Use Survey (Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, United Kingdom, United States). For brevity, in the remainder of this paper we will refer to these geo-cultural contexts as “East Asian” and “Western” countries. For consistency we capitalize Western, while recognizing that it is not a coherent geographic entity and not capitalizing it would be grammatically correct.

Using this novel dataset, the main aim of this project is to examine if there are broad commonalities in time-use patterns among older populations in East Asia, and how these patterns compare to those in Western countries. We focus on four key dimensions of daily life: paid work, domestic work, leisure, and sleep (we motivate this decision in the Methods section). Further, given that gender roles and expectations shape what individuals spend their time on (Avital, 2017; Burgard & Ailshire, 2013; Hochschild & Machung, 2012; Sayer, 2005) and that gender gaps in life expectancy are likely to amplify the gender gaps in care burden (Dentinger & Clarkberg, 2002), the second aim of this study is to assess variation in time-use patterns for older women compared to older men. Lastly, because individuals’ education plays a key role in areas of life that directly impact their time budgets (Feng et al., 2019; He & Baker, 2005; Hofäcker & Naumann, 2015; Jones et al. 1998), the third aim of this study is to examine if time-use patterns among older populations vary by educational attainment.

In what follows, we provide a comprehensive review of prior literature on the linkages between time-use and welfare policies, gender roles, and educational attainment in East Asian and Western societies. Next, we describe the data and analytical approaches used in this study. Finally, we present and interpret the findings. To conclude we discuss directions for future research and policy implications stemming from this study.

Theoretical Background

Welfare Regimes and Time-use

With the establishment of the welfare state, problems such as poverty, illness and disability in old age that have traditionally been managed within families also came to be recognized as the state’s responsibility (Aysan & Beaujot, 2009). The main aim of generous pension policies, as available in some Western countries, is to enable older adults to maintain a decent standard of living after leaving gainful employment (Ebbinghaus, 2021; Gruber & Wise, 2009). Within Western contexts, we examine four welfare regimes based on the frameworks by Esping-Andersen (1990) and Sainsbury (1999) (for similar approach see Aysan & Beaujot, 2009). Democratic Liberal regimes (UK, US, and Canada) characterized by limited governmental and institutional support towards the welfare of families and individuals. State funded pensions are limited and reliance on family resources in old age is common, resulting in large social inequalities in old age. Social Democratic regimes (Denmark, Finland, and Norway) featuring strong governmental support for care provision and comprehensive pension policies aiming to reduce gender and social inequalities. Conservative regimes (France and the Netherlands) where pensions are jointly contributed by the state and employers through employment. Given gender and educational pay gaps from labor market activities, this system tends to reinforce social inequalities. Southern European regimes (Italy and Spain) characterized by welfare policies built on traditional family relations which reinforce gender inequalities within the household and the job market. For a comprehensive comparison of these systems see Anxo et al. (2011).

In Western societies, retirement has been established as a social institution for over several decades with a fixed retirement age and pension (Baumann et al., 2020; Walker, 2002). Retirement is based mainly on chronological age (usually 60 or 65). After reaching the legal retirement age, people expect to be freed from the obligation of paid work and be able to pursue discretionary activities (Baumann et al., 2020).

In East Asian societies, the welfare and pension systems are less developed compared to Western societies. The demographic old-age to working-age ratio (defined as the projected number of people aged 65 and over per 100 people aged between 20 and 64) was 52.0 in 2020 in Japan, which is the highest in East Asia and OECD countries (OECD, 2019). The figures in South Korea and China were 23.6 and 18.5, respectively. Therefore, in East Asian societies it is common for people to work after they have reached the legal retirement age.

China and Taiwan are characterized by a statist pension system where publicly funded pensions provide security for old age (Yeh et al., 2020). However, inequalities between urban and rural areas remain, as agricultural workers have limited access to state funded pensions (Feng et al., 2019). In South Korea, a relatively young pension system can also be thought of as being “under-developed” because it provides insufficient financial support, and only to half of people over 65 years old (Lee & Yeung, 2020). In Japan a dualist pension program, of both public and private nature provides older adults’ income after leaving gainful employment (Yeh et al., 2020). The pension spending in Japan is above OECD average (OECD, 2021a, b). However, because a part of pensions is privately sourced (i.e., funded by individual accounts), a clear gap in old-age financial security between Japan’s socio-demographic groups remains (Yeh et al., 2020). Further, more so than in Western contexts, in East Asian countries it is still common for older adults to rely on their families for care and financial support (Ng, 2011). This is partly because of traditional Confucianist values which encourage adult children to look after their older parents (Park & Chesla, 2007). But also, because East Asian countries have prioritized economic development over social redistribution (Gough, 2001; Holliday, 2000; Lee & Ku, 2007), while also adopting special features limiting the generosity of the state, thus constraining the expansion of welfare systems (Jacobs, 1998). During the past few decades, as families’ capacity to care for older adults significantly diminished, there have been extensive demands to improve pension coverage and social benefits in order to provide better economic security in later life (Yeh et al., 2020). However, due to rapid population ageing (Balachandran et al., 2020) as well as economic crises (Kwon, 2005), policy responses to such demands have been insufficient, resulting in high levels of social inequality and poverty among older populations (Yeh et al., 2020). The income poverty rate (i.e., percentage of people with incomes under 50% of equivalent median household disposable income) for people aged 66 to 75 is 17% in Japan, 38% in China, 27% in Taiwan, and 45.7% in South Korea, compared to 12.5% in the OECD countries (OECD, 2017). Thus, to make ends meet, in East Asia, older people work beyond the lowest legal retirement age whereas in most Western countries the difference between effective and legal retirement age is close to zero or negative (OECD, 2015a, b, 2017, 2018). Indeed, as reported by the OECD (2019), in nearly all East Asian countries, paid work rather than pension is the primary source of income for older people aged 60 and above. Taking these contextual factors into account, we expect that older adults in East Asia will work longer hours for pay compared to their counterparts in Western contexts.

Gender Roles and Time-use

An extensive literature documents how gender roles and expectations shape time-use patterns of men and women, over the life-course (for a recent review see Perry-Jenkins & Gerstel, 2020). Specifically, despite increasing popularity of egalitarian gender attitudes in recent decades (Boehnke, 2011; Knight & Brinton, 2017; Pepin & Cotter, 2018) in both Western and East Asian societies, women continue to be the primary caregiver, while men are overwhelmingly expected to provide for the family (Collins, 2019; Tsai, 2006).

In Western societies, different welfare regimes interact with gender structures, leading to variation in gendered time-use patterns (Geist, 2005; Kan et al., 2011). Prior work finds that gender gaps in time-use are smallest in Social Democratic regimes which have pioneered legislation and social policies aimed at reducing gender gaps in marketplace and family provision, followed by Conservative regimes which provide more assistance to families than Democratic Liberal regimes, and Southern European countries characterized by large gender gaps in family roles (Anxo et al. 2011; Collins, 2019; Craig & Mullan, 2010; Cutillo & Centra, 2017; Gornick & Meyers, 2008; OECD, 2021a).

In East Asian societies, despite rapid social change and economic growth, there is limited change in family expectations and obligations (Raymo et al., 2015). This is partially attributed to the long history of Confucianist ideology which emphasizes gender-specific orders and patriarchal structures (Tsai, 2006). But is also driven by low spending on family benefits, and reliance on women to provide care work, which in turn helps perpetuate women’s disadvantages in the labor market (for Japan and South Korea see OECD, 2021b). As a result, large gender-based inequalities continue to prevail in these societies.

Drawing on previous literature, we expect that in old age women will continue to take on less paid work and more domestic work, and enjoy less leisure time compared to men, as they shift from caring for own children to caring for grandchildren and other older kin (Anxo et al. 2011), across contexts. This trend is likely to be more pronounced in contexts with strong norms of filial piety, inadequate older adults’ care policies, strong role of family as a safety net, and multigenerational living arrangements like East Asian and Southern European contexts (Avital, 2017; Isengard & Szydlik, 2012; Yasuda et al., 2011). For sleep we expect small differences by gender—women having more than men—in Western contexts (Burgard & Ailshire, 2013) and no difference, or differences favoring men rather than women in East Asian and Southern European contexts (Park et al., 2001).

Educational Attainment and Time-use

Prior research shows that educational attainment is a key factor in how individuals’ use their time via mechanisms such as: employment type, household income, knowledge about healthy behaviors (Altintas, 2016; Kalil et al., 2012; Meara et al., 2008; Ross & Wu, 1995).

Recent research (Wu et al., 2020) suggests that education-based inequalities in old age, compared to working age, are shrinking in societies with functional provision policies for older individuals. However, inequalities remain.

In Western societies, on average, higher educated adults continue working for pay longer than lower educated adults because they enjoy stable, better paid jobs, and better health (König et al., 2016; Zajacova & Lawrence, 2018). Thus, we expect that higher educated older people will report more time in paid work compared to lower educated older people. Further, having more income to outsource housework, and less discretionary time, we expect that higher educated older people will report less domestic work than lower educated counterparts. Finally, because leisure time depends in part on the length of one’s employment hours, we also expect that higher educated older people will enjoy less leisure than less educated older people. We expect a similar pattern for sleep.

In East Asia, we expect to find the opposite patterns with lower educated older people reporting more time in paid work, less leisure, and less sleep, but the same or more time in domestic work because they lack the financial resources to outsource domestic labor (Yeh et al., 2020). This is because in East Asian contexts lower educated older people are less likely to access formal sector pension (compared to highly educated older people) and continue working for pay past the normative retirement age (World Bank, 2015; Yeh et al., 2020).

Overall, we expect that in contexts with more generous welfare benefits and support in the form of older adults’ care and pension such as in Social Democratic (Denmark, Finland, Norway) and Conservative regimes (France, the Netherlands), the educational gradient in time-use among older populations will be weaker, compared to the East Asian, Democratic Liberal (UK, US, Canada) and Southern European (Italy, Spain) contexts where old age safety net is more dependent on individual’s characteristics such as their educational attainment.

Methods

Data and Analytic Samples

We pooled data across the cross-sectional waves of the time-diary surveys from each of the 14 countries included in this study to examine daily time-use budgets among older populations. Time-diary surveys ask respondents to recall (or self-record), in sequence, the activities of the previous 24-h day (or of a sampled day; for a review of time-diary methodologies see Bartlett & Milligan, 2015; Robinson, 2002).

To make the data comparable across national contexts, we conducted a pioneering effort and harmonized the data from four East Asian countries (China, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan) with data from ten Western countries included in the Multinational Time Use Study and collected between 2000 and 2015 (Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, United Kingdom, and United States; Fisher et al., 2018; https://www.timeuse.org/mtus).Footnote 1 The harmonized East Asian surveys included: the Chinese Time Use Survey (2008 wave; http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/); the Japan Survey of Time Use and Leisure Activities (2001 and 2006 waves; https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/shakai/index.html); the Korean Time Use Survey (2004, 2009, and 2014 waves; http://kostat.go.kr/portal/eng/index.action); the Taiwan Survey of Social Development Trends (2000 and 2004 waves; https://srda.sinica.edu.tw/index.php). Details about the mode of data collection, collector, survey years, and survey titles, for each country are available in the Appendix, Table A1.

Because the focus of our analysis is on the time-use patterns of older populations, we retained in the sample respondents aged 60 to 75 years old,Footnote 2.Footnote 3 Our aim was to document the daily time-use budgets of functional older populations (Salomon et al., 2012), who are close to retirement age, or have recently retired (König et al., 2016; Yeh et al., 2020). We capped the sample at age 75 to limit the share of respondents who may suffer from serious health issues (Herd, 2006; Salthouse, 2009) which in turn would be reflected in their daily routines; and to limit sample selection bias linked to higher mortality at older ages (Statista 2021). Only primary activities (i.e., activities that were respondent’s main focus) were included in this analysis. Secondary activities (i.e., other activities done at the same time with the primary activity) were not included in this analysis. Note that we retain non-doers in the analysis (i.e., respondents who reported no time in a specific activity as for example paid work, either because they did not participate in that activity the day of the diary or because they do not engage in that activity in general (e.g., retired respondents) (for a similar approach see Negraia et al., 2018).

The analytic sample contains only a few outlier cases (see Appendix, Table A2 for details). Prior research suggests that people report their time use rather accurately in time use diaries at old ages (Sayer et al., 2016), and that age is not associated with systematic error in time use data (Kan 2008; Kan and Pudney 2008). Therefore, in line with previous time use research (Adjei et al., 2017; Anxo et al., 2011; Hertog et al. 2021; Kan et. al. 2011), we did not exclude outlier cases from the analytical sample.

We grouped the 14 countries in our study into eight study samples. The East Asian countries which represent the first four samples, were analyzed separately because little is known about differences in time-use patterns between these populations: Sample 1 (China; N = 9,280), Sample 2 (Japan; N = 118,791), Sample 3 (South Korea; N = 23,776), Sample 4 (Taiwan; N = 9,900). The Western countries were grouped into four samples according to welfare regime based on the framework of Esping-Andersen (1990) and Sainsbury (1999; for a similar approach see Aysan & Beaujot, 2009): Sample 5 = Southern European regimes (Italy, Spain; N = 30,408), Sample 6 = Social Democratic regimes (Denmark, Finland, Norway; N = 3,862), Sample 7 = Conservative regimes (France, the Netherlands; N = 11,069), and Sample 8 = Democratic Liberal regimes (Canada, UK, US; N = 37,493).Footnote 4

Key Measures

Dependent Variables

Time Spent in Major Daily Activities. The main aim of this project was to document how older individuals spend their time across four major daily activities: paid work, domestic work, leisure, and sleep (for similar approaches see Anxo et al. 2011; Van der Lippe et al., 2011). We focus on these broad categories because they capture a large share of individuals’ daily lives but also because they have clear implications for social inequalities (Blair-Loy et al., 2015; Chatzitheochari & Arber, 2009; Luyster et al., 2012; Ng & Popkin, 2012; Thompson & Dahling, 2019). Paid work included time spent working in the labor market (i.e., any income generating work, traveling as part of work, job searching). Domestic work captured household related chores and care activities such as: cooking, cleaning, shopping, home/vehicle maintenance, child-care, and older-adult-care. Leisure included socializing and recreational activities such as: practicing sports, going to the cinema, visiting friends, playing games, reading, watching television. Sleep captured any time spent sleeping or napping.Footnote 5

Welfare Regimes

As discussed in the Introduction section (see above), prior work suggests that macro-level factors such as the welfare regimes practiced in each country can structure how people spend their time (e.g., length of hours spent doing paid work/day). To capture the effect of various welfare regimes on the daily time budgets of older populations, we conducted analyses separately by country/welfare regime, for a total of eight samples as described in the Data section (see above).

Independent Variables

Sex reflects respondents’ self-reports of whether they identified as male (= 0) or female (= 1). Additional questions about respondents’ gender identity (man, woman, transgender, other identities) were not available in the data. We used this measure of sex as a proxy for respondents’ gender, although we recognize that sex and gender identities are non-binary and do not always correspond with each other. Education level is based on respondents’ highest degree attainment and was operationalized as: less than higher secondary education (= 1), higher secondary education (= 2), more than higher secondary education (= 3).

Covariates

All models included controls for respondent, household, and survey characteristics, which previous work has shown to be associated with time-use patterns (Bianchi et al., 2006; Kan and He 2018; Kolpashnikova and Kan 2020a): age (continuous) and age squared, partnership status (0 = not partnered/single; 1 = partnered/married/cohabiting); number of adults living in the household (measured continuously, ranging from 1 to 12); urbanicity (i.e., whether the household is located in an urban area coded as 0 = no; 1 = yes)Footnote 6; whether the diary was collected on a weekday (= 1) or a weekend (= 0); and survey year (ranging from 2000 to 2015).Footnote 7

Analysis Plan

Like other studies (Adjei & Brand, 2018; Sullivan et al., 2018), we modeled our four dependent measures—time spent in paid work, domestic work, leisure, and sleep—continuously (total minutes/day). As explained above, data were pooled across the available survey waves—within each of the 14 countries included in this study—and treated as cross-sectional. In the first part of the analysis, we conducted binary analyses, separately for each activity type, to provide a descriptive understanding of the time-use patterns of older populations across the eight study samples. Next, we repeated this step by respondents’ gender, and afterwards by education level to document differences in time-use patterns for these subgroups. In the second part of the analysis, we repeated these same steps, this time using ordinary least squared (OLS) regression models to test if patterns documented in the descriptive analyses persisted when controlling for the set of covariates described above. We used OLS instead of Tobit models, which are traditionally used to deal with the high volume of zeros typical for time-use data because of evidence suggesting that OLS estimates are similar to those obtained from Tobit models (Foster & Kalenkoski, 2013) and that OLS estimates are “unbiased and robust to a number of assumptions about the relationship between the variables in the model and the probability of doing an.

activity” (Stewart, 2013). Finally, we conducted several additional analyses to check the robustness of our findings including: a) models controlling for respondent’s employment status, b) models looking at respondents ages 70 to 75 years, c) models exploring the interplay between passive and active leisure. We provide theoretical justification for each of these additional analyses, below, in the Supplementary Analyses and Robustness Checks section. All analyses included weights so that the proportion of weekdays to weekends was 5:2 and each country-year shared the same proportion of the full sample. The percentage of missing data on the variables included in our models was low (< 1%). For this reason, we used listwise deletions, instead of multiple imputation (Allison, 2003). Analyses were conducted in STATA 16.

Findings

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics (weighted means and percentages) for socio-demographic characteristics of older respondents across the eight study samples separately and pooled together. The average age of respondents across samples ranges between 65 and 67 years old. Women represent roughly half of each sample, more in Sample 8 (Canada/UK/US) with 57%, and less in China with 47%. The distribution of respondent’s education levels varies between samples. Most respondents from China, South Korea, Taiwan, and Sample 5 (Italy/Spain) reported having Less than higher secondary education (range: 68% to 87%). In Samples 6 (Denmark/Finland/Norway), 7 (France/the Netherlands), and 8 (Canada/UK/US) respondents are somewhat more evenly distributed across educational gradients. The share of partnered (i.e., married or cohabiting) respondents ranges between 73 and 87% across samples, except for Sample 8 (Canada/UK/US) where 55% of respondents reported being partnered. On average, there were more than two adults (range: 2.38 to 2.86) co-residing with the respondent in East Asian countries and Sample 5 (Italy/Spain), and less than two adults (range: 1.83 to 1.91) in Samples 6 (Denmark/Finland/Norway), 7 (France/the Netherlands), and 8 (Canada/UK/US).

Bivariate Analyses

Time-use Budgets of Older Respondents across Countries/Regions

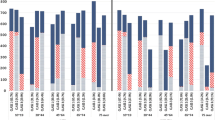

In the first step of the analysis, we examined the daily time-use budgets of older respondents across the eight study samples. We report average time spent in major daily activities in minutes/day, in Fig. 1. However, to facilitate comprehension of these descriptive statistics we summarize them here, in hours/day. We found that older respondents from East Asian countries, reported on average more time in paid work (between 1.8 and 2.6 h/day) compared to older respondents from Western countries (between 0.5 and 1.5 h/day). Next, we found that older respondents from East Asian countries reported spending, on average, less time doing domestic work (between 1.8 and 3 h/day) than older respondents from Western countries (between 3.3 and 4.3 h/day). For leisure and sleep, patterns are less differentiated. For leisure, respondents from China reported the least amount of time spent in leisurely activities (5.6 h/day) while respondents from the other samples reported between 6.3 and 7.4 h of leisure per day. However, for sleep, older respondents from China (9.5 h/day) and Taiwan (9.2 h/day) reported the most time sleeping with the other samples reporting between 8 and 9 h of sleep daily.

In sum, older respondents in East Asian countries undertook far more paid work and less domestic work than their counterparts in Western countries. Overall, time spent in leisure activities was somewhat similar across countries, but older adults in China, Southern European (Italy/Spain) contexts, and Japan enjoyed less leisure time than respondents from the other countries/regions; and older adults in China and Taiwan reported the longest sleep periods.

In supplementary analyses where we explored patterns separately for employed vs. not employed respondents (except for France where information on employment status is missing) we found that for the employed group, patterns were similar to those reported in the main analysis, although differences between East Asian and Western contexts were smaller (see Appendix, Figure A1). Interestingly, for the unemployed group, in China and Japan, respondents still reported on average 40 min of paid work per day – compared to less than 10 min in other regions – likely indicating that in these contexts some older adults continue working for pay into their retirement, in family farms, or in informal markets.

Next, we conducted binary analyses exploring variation in the daily time-use patterns of older adults, separately for women and men, and then by respondent’s education levels. However, because these patterns were similar to the multivariate results which we will present next, we report these descriptive findings in the Appendix, see Figures A2 and A3.

Multivariate Regression Analyses

In the second part of the analysis, we ran multivariate regression models (OLS) to test if the descriptive patterns obtained from bivariate analyses remained when we controlled for the relevant covariates described above (see Measures section). To facilitate the comprehension and visualization of these time-use patterns we graphed the regression coefficients, and we report these in Figs. 2 and 3 (see Appendix, Tables A3 to A6, for full regression coefficients).

Point estimates and 95% confidence interval of gender difference (women vs. men) in time-use among older people, across countries/regions. Note: The X axis presents difference in time (minutes/day) between women and men, aged 60 to 75, for four separate daily activities. Negative values indicate that men do more of that activity; positive values indicate that women do more of that activity. Results from OLS models, estimated separately for each activity and including controls for individual level factors (gender, age, age squared, education level, household size, urban area). Coefficients and cell sizes are available in the Appendix, Tables A2-A5

Point estimated and 95% confidence interval of time-use among older people, by educational level (reference group: less than higher secondary education). Note: The X axis presents difference in time between respondents with Higher Secondary Education and those with Less than Higher Secondary Education (blue lines); and More than Higher Secondary Education and those with Less than Higher Secondary Education (read lines); aged 60 to 75, across daily activities. Negative values indicate that the reference group (Less than Higher Secondary Education) do more of that activity; the reverse for positive values. Results from OLS models, estimated separately for each activity and including controls for individual level factors (gender, age, age squared, education level, household size, urban area). Coefficients and cell sizes are available in the Appendix, Tables A2-A5

Gender Gaps in Time-use Budgets of Older Respondents

First, we examined the size (minutes/day) of the gender gaps in daily time-use between older women and older men within each country/regional context (see Fig. 2). The X axis shows the difference in time between women and men, with negative values indicating that men reported more of that activity, and a positive value indicating that women reported more of that activity. For paid work, we found that across countries, older women reported significantly less time working for pay than men did; and that this gender gap in paid work was larger in East Asian (a difference of 80 to 100 min/day) than in Western contexts (a difference of 30 to 40 min/day), even after controlling for characteristics like respondents’ age, partnership status, education level. The largest gender gap was in Japan, where older women reported working for pay about 100 min less than older men. For domestic work, we found that women did more than men, across countries. The size of this gender gap was larger in East Asian countries and Southern European (Italy/Spain; a difference of 150 to 200 min/day) than in Social Democratic, Conservative, and Liberal Western countries (a difference of 60 to 75 min/day), even after controlling for relevant covariates. For leisure, we found that women enjoyed less leisure time than men did, across countries. Strikingly, women in Southern European (Italy/Spain) contexts spent 110 min less per day on leisure than men. The gender gap in leisure was also substantive in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan with a difference of 60 to 80 min. The smallest gender gap in leisure was in Social Democratic countries (Denmark/Finland/Norway; approximately 30 min per day). For sleep, in analyses controlling for relevant covariates, consistent with the bivariate results, we found little or no gender differences for respondents from Social Democratic, Conservative, and Liberal contexts. In China, older women reported more sleep time than men. However, in Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Italy/Spain, older women reported less sleep time than men. The largest gender gap in sleep time was in Japan, where women reported sleeping about half an hour/day less than men.

In sum, results from multivariate regression analyses exploring variation by respondents’ gender showed clear gendered time-use patterns among older adults in all the countries studied. Overall, men spent more time on paid work, less time on domestic work, and more time on leisure than women, across contexts. The gender gaps in time-use are substantially larger in the four East Asian countries than in the Western countries we studied (except for Italy/Spain). The gendered patterns in time-use are the most distinctive in Japan and Italy/Spain, where women reported far more domestic work, less leisure, and sleep less than men.

Educational Gradients in Time-use Budgets of Older Respondents

Next, we present results from multivariate OLS regressions assessing differences in time-use budgets of older adults across education levels (less than higher secondary education = reference group). To facilitate the visualization of the patterns we graphed the coefficients, and we present them in Fig. 3 (full regression coefficients are reported in Appendix, Tables A3-A6).

We found that in all East Asian countries, the more educated groups reported less time in paid work (between 20 and 40 min) than the least educated group. We observed the opposite association in Western countries, where more educated older adults reported spending more time in paid work (between 5 and 50 min) than the least educated respondents.

Looking at time spent in domestic work, we found that, overall, respondents’ education levels made little or no difference, in East Asian countries. In Western countries (except Canada/UK/US), more educated respondents spent less time on domestic work, but the difference is mainly between those with highest (i.e., above higher secondary educational level) and those with lowest education levels (i.e., less than higher education levels). This observation concurs with the finding that more educated older adults in these countries spend more time on paid work.

Moving on to leisure time, in East Asian countries we observed leisure time inequality by educational level, especially in South Korea and Taiwan where more educated older adults reported more leisure compared to the least educated group. Pairing this finding with the negative educational gradient in paid work, we can say that there is a time inequality in East Asian countries where least educated older adults enjoy less leisure and work for pay more than their more educated counterparts. In Southern European contexts (Italy/Spain) we observe the same pattern where more educated older adults enjoy more leisure time compared to their least educated peers. Democratic Liberal regime (Canada/UK/US) is the only context where higher educated older adults reported less leisure than the lowest educated group. For Social Democratic (Denmark/Finland/Norway) and Conservative (France/Netherlands) regimes, overall, we do not observe clear differences in leisure time by education level.

Finally, for sleep, in all countries educational attainment was negatively associated with sleep time; with highest educated respondents sleeping least (except for China where we observe no association). The educational gradient in sleep time is stronger in Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Southern European (Italy/Spain) contexts, compared to the other Western contexts where older adults with highest education levels reported spending less time sleeping than less educated older adults. In these countries, older adults with “higher secondary education” slept around 20 min less per day, and older adults with “above higher secondary education” slept around 35 min less per day than people with “below higher secondary education”.

To sum up, for paid work, we observed a distinct and clear pattern in the four East Asian countries, with more educated older adults working less than the least educated group. The Southern European (Italy/Spain) region joins the East Asian countries with more educated people spending more time on leisure and less time on sleep than the least educated group. For domestic work, the patterns of associations between education levels and time use among the countries included in this study are less clear cut.

Supplementary Analyses and Robustness Checks

Models Controlling for Employment Status

In the main analysis, we present estimates from regression models without the control for employment status (1 = employed, 0 = not employed) because the employment indicator is missing for France, one of the countries in Sample 7 (Conservative regimes). Thus, this approach enabled us to keep France in the Main Analysis.

However, time spent in paid work between older men and women is expected to vary with respect to labor force participation and this variation to be systematically different by country. Therefore, including a control for employment status in our models should provide more accurate estimates of the time budgets of older men and women, particularly for the dimension of paid work, but also for the other time contexts explored in this study. We re-ran our multivariate regression models, this time also including a control for respondents’ employment status (1 = employed, 0 = not employed). Results are reported in the Appendix, Tables A7-A10 and Figure A4. Note: this robustness check does not include France, because employment status is not available for France. For paid work, in models controlling for employment status we found that older women continue to report less time in paid work than men, across contexts, except for Japan, where the difference is no longer significant (see Table A7, Figure A4). Further, for paid work, the difference between East Asian and Western regions is no longer as clearly defined as in the main analysis, where the gender gap in paid work was much larger in East Asian countries compared to Western regions. Thus, while this regional difference becomes less relevant, the finding that in old age, women do less paid work than men, is supported by this robustness check where we control for employment status, in all contexts, except for Japan. Moving on to the gender gaps in time spent in domestic work, leisure, and sleep (see Tables A8-A10, Figure A4), the OLS models controlling for employment status revealed very similar patterns to those reported in the main analysis where we did not control for employment status. Finally, patterns by education levels from models where we controlled for respondents’ employment status (see Appendix, Figure A5) were similar to those reported in the main analysis.

Respondents Aged 70–75

Because retirement age varies across the countries included in this study, and retirement—or the lack of paid employment—plays an important role in structuring people’s daily time budgets, we repeated the analysis steps by gender and education on a sample of respondents aged 70 to 75 when we would expect that many respondents included in these data would have retired. We found that for paid work, time gaps by gender and education shrink at ages 70 + , and differences between the East Asian countries and Western contexts are less well defined. However, patterns for domestic work, leisure, and sleep are overall similar in the full sample (60 to 75 years old) and the oldest age group (70 to 75 years old). Tables and Figures are available in the Appendix (see Tables A11-A14, and Figures A6-A7).

The Interplay between Passive and Active Leisure

In our main analysis we explore differences in broad leisure time which is merging together dimensions of active and passive leisure. We did so in order to simplify the already complex design of our study. However, inequalities in active vs. passive leisure have different implications for population health (Bohn et al., 2017). Therefore, in supplementary analyses we explored if and how the patterns in broad leisure reported in the main analysis differ when we disentangle between active and passive forms of leisure. Our measure of active leisure includes activities such as relaxing, socializing, volunteering, organization work, religion, going out, sports and exercising. Our measure of passive leisure includes activities such as reading, listening to the radio, watching television, browsing the internet on a computer. We re-ran our multivariate models including these two additional outcome variables (see Appendix, Tables A15, A16 and Figures A8 and A9) and found that for gender, the patterns in active leisure largely mapped those for broad leisure, which is the leisure measure reported in the main analysis. Specifically, for active leisure, in East Asian countries and South European countries, older women reported significantly less active leisure than older men (see Appendix, Tables A15-A16, Figure A8). In Social Democratic (Denmark, Finland, Norway) and Democratic Liberal (Canada, UK, US) regimes, we actually found that gender gaps in active leisure are reversed – with women enjoying more time than men. In Conservative regimes (France, the Netherlands) we found no gender differences in active leisure.

Moving on to Passive Leisure (see Appendix, Tables A15-A16, Figure A8), the gender gap – with men enjoying more passive leisure than women – remains for each country/region. Interestingly, when we compare across broad, active, and passive leisure, for regions 6 (DK/FI/NO), 7 (FR/NL) and 8 (CA/UK/US), we observe that the gender gap in leisure is mainly a gap in passive leisure, where men in these contexts enjoy more passive leisure than women do, but gaps in active leisure are much smaller or not statistically significant. For East Asian and South European contexts however, the gender gaps in leisure are composed of gaps where women enjoy both less active and less passive leisure than men do.

This additional analysis also provides some refinement for our findings regarding gaps in leisure patterns by education level (see Appendix, Figure A9). Specifically, in Japan and South Korea higher educated older adults report more active leisure than their less educated counterparts; while in China, Taiwan and Southern European societies higher educated older adults report more passive leisure than their less educated counterparts. We find no gap in leisure time by education in Social Democratic (Denmark, Finland, Norway) and Conservative (France, the Netherlands) regimes. Interestingly, the Democratic Liberal regime (Canada, UK, US) is the only context where higher educated older adults report both less active and less passive leisure compared to less educated older adults.

Discussion

Most prior work examining daily time-use patterns has focused on working adults (Sullivan et al., 2018), and little is known about the lives of aging adults. As population demographics change and the share of aging adults continues to grow (He et al., 2016), it is imperative that we turn our attention to the lives of aging adults to examine how they use their time. Our aims were to make such advancements and document the daily time-use patterns of older populations (ages 60 to 75) at the intersection of gender and educational levels, using a cross-cultural framework comparing East Asian and Western societies. We did this by harmonizing time-diary data collected between 2000 and 2015 from multiple national survey agencies in East Asia (China, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea) with the Multinational Time Use Study (MTUS) capturing selected Western countries which we grouped based on their common welfare regimes (Esping-Andersen, 1990; Sainsbury, 1999): Democratic Liberal (Canada/UK/US), Social Democratic (Denmark/Finland/Norway), Conservative (France/the Netherlands), Southern European (Italy/Spain).

We found a clear difference in time spent in paid work by older individuals in East Asian contexts who reported working significantly longer hours for pay than their Western counterparts. This pattern is in line with our expectations, informed by the later development of welfare policies, and continued employment into retirement age to avoid old age poverty in East Asian countries (OECD, 2017). Surprisingly, when we refined our analysis by respondents’ gender, we found that East Asian older women reported more time in paid work than Western older men. This may be explained by higher risk of poverty in old age in East Asian contexts, therefore pushing lower educated women who are potentially agricultural workers, to continue working past retirement age (Yeh et al., 2020). Our analyses did not explore intersections between gender and education levels, which would allow to examine the potential mechanisms behind this finding. We leave this to future work. Further, as expected, we found that lowest educated older adults in East Asian contexts reported more paid work compared to their more educated counterparts. This is likely because highly educated older adults are more likely to have access to private savings, and formal pension plans allowing them to exit the labor market; while pension plans for the least educated older adults are insufficient thus pushing them to remain in the labor market (Yeh et al., 2020). We observed the opposite trend in Western contexts, where highest educated older adults reported more paid work time than lowest educated older adults. This may be because they are employed in well-paying jobs, but also because they are less likely to suffer from physical disabilities which push lower educated older adults out of employment (König et al., 2016).

For domestic work, we found that, overall, older respondents in East Asian countries reported less domestic work compared to their Western counterparts. This pattern is consistent with the paid work trends because one has less time for domestic work if they spend a large share of their day in paid work. Gender patterns revealed that, overall, women reported similar time in domestic work, across contexts, but East Asian older men reported less time in domestic work compared to any other group. These findings provide some support for the idea that despite rapid economic growth, gaps in gender roles and expectations in East Asian countries remain large and are slow to change (Raymo et al., 2015). Indeed, analyses where we explored the size of the gender gaps showed that gender gaps in domestic work were largest in East Asian contexts, especially Japan, and smallest in Western contexts, except for Southern European contexts (Italy/Spain) which was preceded only by Japan. Nevertheless, future research should explore if these gaps remain when comparing men and women of similar educational backgrounds. Potential explanations for the smaller gender gaps in domestic work in Western contexts (except Italy/Spain) may be because in recent decades men have increased their contribution to domestic housework while women decreased theirs (Bianchi et al., 2012). These findings suggest that gender gaps in domestic work documented among working age adults (Perry‐Jenkins and Gerstel 2020) continue into older age and are largest in traditional contexts with strong gender normative expectations like East Asia and Southern European contexts.

The amount of daily leisure time that people have depends mainly on their discretionary time left after paid work and unpaid work responsibilities have been fulfilled. Given the large gender time difference from domestic work, it is not surprising we found that older women reported spending less time on leisure across countries. This finding extends knowledge from prior work on gender gaps in leisure time (Craig & Mullan, 2013; Yerkes et al., 2020), by showing that these patterns persist into old age with women enjoying less time to relax and recharge compared to men across all contexts; gaps were largest in Southern European countries (Italy and Spain), followed by East Asian countries, and smallest in Social Democratic contexts (Norway, Denmark, and Finland). This finding mirrors patterns for domestic work which show that gender gaps were largest in countries with traditional gender roles. Patterns refined by respondents’ education level, revealed that in East Asian contexts, higher educated older adults reported more time in leisure compared to their less educated counterparts. A pattern that was also found in Southern European (Italy/Spain) contexts. In the other Western contexts, we found little variation in leisure time by educational level among older adults in Conservative (France/the Netherlands) and Social Democratic (Denmark/Finland/Norway), but more in Democratic Liberal (Canada/UK/US) regimes where higher educated older adults reported less leisure time compared to their less educated counterparts.

When considering the full sample, for sleep, we did not find major discrepancies across contexts. However, results from multivariate models showed that women slept less than men in Japan and Southern European (Italy/Spain) contexts. This finding complements the findings for domestic work and leisure, where older women reported doing more domestic work and enjoying less leisure time than older men. We found similar patterns, but smaller gaps in South Korea and Taiwan. Our results revealed no gender gaps in sleep for older adults in the other Western contexts. Interestingly, when we examined educational gradients, we found that higher educated older adults in East Asian contexts (except for China where there was no effect), reported significantly less time sleeping than their less educated counterparts. Given that higher educated older adults do less paid work than least educated older adults, this finding is potentially explained by their higher share of leisure time. In Western contexts educational gradients were again smaller than in East Asian contexts. Future work should examine sleep interruption (number of awakenings) in both East Asian and Western contexts, as prior work has suggested that women are at a disadvantage (Burgard & Ailshire, 2013; Park et al., 2001).

This work makes multiple key contributions to the study of older populations. First, to our knowledge, this study is the first to document the diverging destinies of vulnerable older groups in East Asia (women, and lower educated older adults) who need to continue working for pay (lower educated older adults), do disproportionately more domestic work and less leisure (older women) compared to the highest educated older adults and compared to older men. These findings suggest that in East Asia, the pension and welfare systems do not provide equal provisions to people with different levels of education, and lower educated older adults are more likely to be “pushed” to work after their normative retirement age and hence have their leisure time reduced. Second, these findings highlight that gender differences in time use among aging populations are much larger in the East Asian contexts, especially Japan and that patterns of time use between genders do not converge in later life. Third, this study showed that gender differences and educational gradients in time use among older adults in Southern European (Italy and Spain) contexts are more similar to patterns found in East Asian contexts than in other Western contexts. This suggests that in societies where there are strong family and gender norms about care provision, social inequalities in time use are more likely persist in later life. Overall, these findings call for policies aimed at reducing these inequalities and facilitating successful aging for all older adults, across socio-demographic groups in all geo-cultural contexts but particularly in Southern European and East Asian contexts (Nakagawa et al., 2020; Solé-Auró & Alcañiz, 2016). Policies targeted at reducing old age poverty and improving older adults’ care support will be especially relevant. Government subsidized pension schemes that potentially benefit workers from all occupations as well as full-time homemakers should be able to reduce gender and educational inequalities in time use in older age. In addition, a public social protection system for people in need of long-term care should be introduced, as care needs in old age is a major risk for old age poverty, and such a protection system should also reduce the care burden of older women (Hashiguchi & Llena-Nozal, 2020).

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Using pioneering harmonized data and a cross-cultural design, this study made important contributions to the study of inequalities in time-use inequalities among older populations. Yet, limitations remain. First, given the already complex design of the study, we chose to limit the scope of our study to four major dimensions of daily life with clear implications for inequalities. Future research should document time-use patterns among older populations across other daily activities which may also have implications for social inequalities such as time spent eating and drinking (Bowen et al., 2019), and time spent in personal and healthcare activities which become increasingly important as people age and their health deteriorates (Salomon et al., 2012). Second, we report gender gaps in time-use at the population level based on diary reports from individual respondents. Future work should replicate these findings using couple-level data. Third, due to data limitations we were not able to: a) explore time-use inequalities in old age along other socio-demographic characteristics such as race/ethnicity (Kan and Laurie 2018; Kolpashnikova and Kan 2020b) control for household income which would have enabled us to examine why lower educated older adults in East Asian contexts reported more paid work (Yeh et al., 2020); c) control for number of residential grandchildren, or if the household was multigenerational which would have enabled us to disentangle some of the domestic work patterns (Yasuda et al., 2011); d) explore variation in time use inequalities by gender and education over time. We believe these are all important avenues for future work.

This study is one of the first to provide a comprehensive overview of older adults’ time use across East Asian and Western contexts. These findings contribute to our understanding of inequalities in later life by showing that the destinies of older adults in East Asian and Western contexts are strikingly different and are diverging by gender and socioeconomic groups. These findings call for policy makers to prioritize legislation aimed at reducing these inequalities and facilitating successful aging across geo-cultural contexts but particularly in Southern European and East Asian contexts.

Data Availability

Data from the Multinational Time Use Study is publicly available at: https://www.timeuse.org/mtus. Data from East Asian countries is not publicly available but can be requested from each national agency (see links provided in the Methods section).

Code Availability

Harmonization codes are available at https://www.gentime-project.org/data. Codes for data analyses are available at https://osf.io/zm3t6/.

Notes

Harmonization codes are available at https://www.gentime-project.org/data.

If respondents were aged 60 to 75 at the time of data collection (2000 to 2015), then the respondents included in our study are part of cohorts born between 1925 and 1955.

For Japan, due to data limitations, the upper age limit was 74.

See Appendix, Table A1 for total number of diary days, and survey years by country.

See the MTUS user guide (Table 3.1., pages 43–44, https://www.timeuse.org/sites/default/files/9727/mtus-user-guide-r9-february-2016.pdf) for further detail on activity codes.

Information on urbanicity is missing in the MTUS for Samples 6, 7, and 8. To retain this indicator in the analysis, we coded respondents from these samples, as residing in urban areas. Robustness checks where we dropped the urbanicity indicator from the analyses showed very similar patterns as those from the main analysis.

See Appendix, Table A-1 for survey years for each country. Note that some countries include only one survey year. Data from countries including multiple survey years were pooled together and treated as cross-sectional.

References

Adjei, N. K., & Brand, T. (2018). Investigating the associations between productive housework activities, sleep hours and self-reported health among elderly men and women in western industrialised countries. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 110

Adjei, N. K., Brand, T., & Zeeb, H. (2017). Gender inequality in self-reported health among the elderly in contemporary welfare countries: A cross-country analysis of time use activities, socioeconomic positions, and family characteristics. PLoS One, 12(9), e0184676

Allison, P. D. (2003). Missing data techniques for structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(4), 545–557

Altintas, E. (2016). The widening education gap in developmental child care activities in the United States, 1965–2013. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78(1), 26–42

Anxo, D., Mencarini, L., Pailhé, A., Solaz, A., Tanturri, M. L., & Flood, L. (2011). Gender differences in time use over the life course in France, Italy, Sweden, and the US. Feminist Economics, 17(3), 159–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2011.582822

Avital, D. (2017). Gender differences in leisure patterns at age 50 and above: Micro and macro aspects. Ageing and Society, 37(1), 139–166

Aysan, M. F., & Beaujot, R. (2009). Welfare regimes for aging populations: No single path for reform. Population and Development Review, 35(4), 701–720

Balachandran, A., de Beer, J., James, K. S., van Wissen, L., & Janssen, F. (2020). Comparison of population aging in Europe and Asia using a time-consistent and comparative aging measure. Journal of Aging and Health, 32(5–6), 340–351

Bartlett, R., & Milligan, C. (2015). What is diary method? Bloomsbury Publishing.

Baumann, D., Ruch, W., Margelisch, K., Gander, F., & Wagner, L. (2020). Character strengths and life satisfaction in later life: An analysis of different living conditions. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 15(2), 329–347

Bélanger, D., Lee, H.-K., & Wang, H.-Z. (2010). Ethnic diversity and statistics in East Asia: ‘Foreign brides’ surveys in Taiwan and South Korea. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 33(6), 1108–1130

Bianchi, S. M., Robinson, J. P., & Milkie, M. A. (2006). The changing rhythms of American family life. Russell Sage Foundation.

Bianchi, S. M., Sayer, L. C., Milkie, M. A., & Robinson, J. P. (2012). Housework: Who did, does or will do it, and how much does it matter? Social Forces, 91(1), 55–63

Bianchi, S., Lesnard, L., Nazio, T., & Raley, S. (2014). Gender and time allocation of cohabiting and married women and men in France, Italy, and the United States. Demographic Research, 31, 183

Blair-Loy, M., Hochschild, A., Pugh, A. J., Williams, J. C., & Hartmann, H. (2015). Stability and transformation in gender, work, and family: Insights from the second shift for the next quarter century. Community, Work and Family, 18(4), 435–454

Bloom, D. E., Boersch-Supan, A., McGee, P., & Seike, A. (2011). Population aging: Facts, challenges, and responses. Benefits and Compensation International, 41(1), 22

Boehnke, M. (2011). Gender role attitudes around the Globe: Egalitarian vs. Traditional Views. Asian Journal of Social Science, 39(1), 57–74

Bohn, L., Ramoa, A., Silva, G., Silva, N., Abreu, S. M., Ribeiro, F., Boutouyrie, P., Laurent, S., & Oliveira, J. (2017). Sedentary behavior and arterial stiffness in adults with and without metabolic syndrome. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 38(5), 396–401

Bowen, S., Brenton, J., & Elliott, S. (2019). Pressure cooker: Why home cooking won’t solve our problems and what we can do about it. Oxford University Press.

Burgard, S. A., & Ailshire, J. A. (2013). Gender and time for sleep among US adults. American Sociological Review, 78(1), 51–69

Chatzitheochari, S., & Arber, S. (2009). Lack of sleep, work and the long hours culture: Evidence from the UK Time Use Survey. Work, Employment and Society, 23(1), 30–48

Collins, C. (2019). Making motherhood work: How women manage careers and caregiving. Princeton University Press.

Craig, L., & Mullan, K. (2010). Parenthood, gender and work-family time in the United States, Australia, Italy, France, and Denmark. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(5), 1344–1361

Craig, L., & Mullan, K. (2013). Parental leisure time: A gender comparison in five countries. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State and Society, 20(3), 329–357

Cutillo, A., & Centra, M. (2017). Gender-based occupational choices and family responsibilities: The gender wage gap in Italy. Feminist Economics, 23(4), 1–31

Dentinger, E., & Clarkberg, M. (2002). Informal caregiving and retirement timing among men and women: Gender and caregiving relationships in late midlife. Journal of Family Issues, 857–879

Ebbinghaus, B. (2021). Inequalities and poverty risks in old age across Europe: The double-edged income effect of pension systems. Social Policy and Administration

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton University Press.

Feng, Q., Yeung, W.-J.J., Wang, Z., & Zeng, Y. (2019). Age of retirement and human capital in an aging China, 2015–2050. European Journal of Population, 35(1), 29–62

Fisher, K., Gershuny, J., Flood, S. M., Roman, J. G., & Hofferth, S. L. (2018). Multinational time use study extract system: Version 1.2. IPUMS.

Foster, G., & Kalenkoski, C. M. (2013). Tobit or OLS? An empirical evaluation under different diary window lengths. Applied Economics, 45(20), 2994–3010

Geist, C. (2005). The welfare state and the home: Regime differences in the domestic division of labour. European Sociological Review, 21(1), 23–41

Gornick, J. C., & Meyers, M. K. (2008). Creating gender egalitarian societies: An agenda for reform. Politics and Society, 36(3), 313–349

Gough, I. (2001). Globalization and regional welfare regimes: The East Asian case. Global Social Policy, 1(2), 163–189

Gruber, J., & Wise, D. A. (2009). Social security programs and retirement around the world: Micro-estimation. University of Chicago Press.

Hashiguchi, T. C. O., & Llena-Nozal, A. (2020). The effectiveness of social protection for long-term care in old age: Is social protection reducing the risk of poverty associated with care needs? OECD Health Working Papers

He, X. Z., & Baker, D. W. (2005). Differences in leisure-time, household, and work-related physical activity by race, ethnicity, and education. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 20(3), 259–266

He, W., Goodkind, D., & Kowal, P. R. (2016). An aging world: 2015. United States Census Bureau.

Herd, P. (2006). Do functional health inequalities decrease in old age? Educational status and functional decline among the 1931–1941 birth cohort. Research on Aging, 28(3), 375–392

Hertog, E., Kan, M.-Y., Shirakawa, K., & Chiba, R. (2021). Do better-educated couples share domestic work more equitably in Japan? It depends on the day of the week. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 52(2), 271–310. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcfs-52-2-006

Hochschild, A., & Machung, A. (2012). The second shift: Working families and the revolution at home. Penguin.

Hofäcker, D., & Naumann, E. (2015). The emerging trend of work beyond retirement age in Germany. Zeitschrift Für Gerontologie Und Geriatrie, 48(5), 473–479

Holliday, I. (2000). Productivist welfare capitalism: Social policy in East Asia. Political Studies, 48(4), 706–723

Isengard, B., & Szydlik, M. (2012). Living apart (or) together? Coresidence of elderly parents and their adult children in Europe. Research on Aging, 34(4), 449–474

Jacobs, D. (1998). Social welfare systems in East Asia: A comparative analysis including private welfare. LSE STICERD Research Paper No. CASE010

Jones, A. D., Ainsworth, B. E., Croft, J. B., Macera, C. A., Lloyd, E. E., & Yusuf, H. R. (1998). Moderate leisure-time physical activity: Who is meeting the public health recommendations? A national cross-sectional study. Archives of Family Medicine, 7(3), 285

Kalil, A., Ryan, R., & Corey, M. (2012). Diverging destinies: Maternal education and the developmental gradient in time with children. Demography, 49(4), 1361–1383

Kan, M. Y. (2008). Measuring housework participation: The gap between “stylised” questionnaire estimates and diary-based estimates. Social Indicators Research, 86(3), 381–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9184-5

Kan, M. Y., & He, G. (2018). Resource bargaining and gender display in housework and care work in modern China. Chinese Sociological Review, 50(2), 188–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/21620555.2018.1430506

Kan, M.-Y., & Laurie, H. (2018). Who is doing the housework in multicultural Britain? Sociology, 52(1), 55–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038516674674

Kan, M. Y., & Pudney, S. (2008). Measurement error in stylized and diary data on time use. Sociological Methodology, 38(1), 101–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9531.2008.00197.x

Kan, M. Y., Sullivan, O., & Gershuny, J. (2011). Sociology, 45(2), 234–251

Knight, C. R., & Brinton, M. C. (2017). One egalitarianism or several? Two decades of gender-role attitude change in Europe. American Journal of Sociology, 122(5), 1485–1532

Kolpashnikova, K., & Kan, M.-Y. (2020a). Hebdomadal patterns of compensatory behaviour: Weekday and weekend housework participation in Canada, 1986–2010. Work, Employment and Society, 34(2), 174–192

Kolpashnikova, K., & Kan, M.-Y. (2020b). The gender gap in the United States: Housework across racialized groups. Demographic Research, 43(36), 1067–1080

König, S., Hess, M., & Hofäcker, D. (2016). Trends and determinants of retirement transition in Europe, the USA and Japan: A comparative overview. Delaying Retirement, 23–51

Kwon, H. J. (2005). Transforming the developmental welfare state in East Asia. Development and Change, 36(3), 477–497

Lee, Y., & Yeung, W.-J. J. (2020). The country that never retires: The gendered pathways to retirement in South Korea. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B

Lee, Y.-J., & Ku, Y. (2007). East Asian welfare regimes: Testing the hypothesis of the developmental welfare state. Social Policy and Administration, 41(2), 197–212

Luyster, F. S., Strollo, P. J., Jr., Zee, P. C., & Walsh, J. K. (2012). Sleep: A Health Imperative. Sleep, 35(6), 727–734

Mattingly, M. J., & Sayer, L. C. (2006). Under pressure: Gender differences in the relationship between free time and feeling rushed. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(1), 205–221

Meara, E. R., Richards, S., & Cutler, D. M. (2008). The gap gets bigger: Changes in mortality and life expectancy, by education, 1981–2000. Health Affairs, 27(2), 350–360

Musick, K., Bea, M. D., & Gonalons-Pons, P. (2020). His and her earnings following parenthood in the United States, Germany, and the United Kingdom. American Sociological Review, 0003122420934430

Nakagawa, T., Cho, J., & Yeung, D. (2020). Successful aging in East Asia: Comparison among China, Korea, and Japan. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B

Negraia, D. V., Augustine, J. M., & Prickett, K. C. (2018). Gender disparities in parenting time across activities, child ages, and educational groups. Journal of Family Issues, 39(11), 3006–3028

Ng, K.-H. (2011). Review essay: Prospects for old-age income security in Hong Kong and Singapore. Journal of Population Ageing, 4(4), 271–293

Ng, S. W., & Popkin, B. M. (2012). Time use and physical activity: A shift away from movement across the globe. Obesity Reviews, 13(8), 659–680

Nomaguchi, K. M., Milkie, M. A., & Bianchi, S. M. (2005). Time strains and psychological well-being: Do dual-earner mothers and fathers differ? Journal of Family Issues, 26(6), 756–792

OECD. (2015a). “Korea”, in Pensions at a Glance 2015: OECD and G20 indicators. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/pension_glance-2015-65-en

OECD. (2015b). “Japan”, in Pensions at a Glance 2015: OECD and G20 indicators. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/pension_glance-2015-64-en

OECD. (2017). Pensions at a Glance 2017: OECD and G20 indicators. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/pension_glance-2017-graph69-en

OECD. (2018). Pensions at a Glance Asia/Pacific 2018. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/pension_asia-2018-en

OECD. (2019). Pensions at a Glance 2019: OECD and G20 Indicators. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/b6d3dcfc-en

OECD. (2021a). Pension spending (indicator). https://doi.org/10.1787/a041f4ef-en

OECD. (2021b). Family benefits public spending (indicator). https://doi.org/10.1787/8e8b3273-en

Park, M., & Chesla, C. (2007). Revisiting Confucianism as a conceptual framework for Asian family study. Journal of Family Nursing, 13(3), 293–311

Park, Y. M., Matsumoto, K., Shinkoda, H., Nagashima, H., Kang, M. J., & Seo, Y. J. (2001). Age and gender difference in habitual sleep–wake rhythm. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 55(3), 201–202

Pepin, J. R., & Cotter, D. A. (2018). Separating spheres? Diverging trends in youth’s gender attitudes about work and family. Journal of Marriage and Family, 80(1), 7–24

Perry-Jenkins, M., & Gerstel, N. (2020). Work and family in the second decade of the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 420–453

Raymo, J. M., Park, H., Xie, Y., & Yeung, W. J. (2015). Marriage and family in East Asia: Continuity and change. Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 471–492

Robinson, J. P. (2002). The time-diary method. Time use research in the social sciences (pp. 47–89). Springer.

Ross, C. E., & Wu, C. (1995). The links between education and health. American Sociological Review, 719–745

Sainsbury, D. (1999). Gender and welfare state regimes. Oxford University Press.

Salomon, J. A., Wang, H., Freeman, M. K., Vos, T., Flaxman, A. D., Lopez, A. D., & Murray, C. J. (2012). Healthy life expectancy for 187 countries, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden Disease Study 2010. The Lancet, 380(9859), 2144–2162

Salthouse, T. A. (2009). When does age-related cognitive decline begin? Neurobiology of Aging, 30(4), 507–514

Sayer, L. C. (2005). Gender, time and inequality: Trends in women’s and men’s paid work, unpaid work and free time. Social Forces, 84(1), 285–303

Sayer, L. C., England, P., Bittman, M., & Bianchi, S. M. (2009). How long is the second (plus first) shift? Gender differences in paid, unpaid, and total work time in Australia and the United States. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 40(4), 523–545

Sayer, Liana C., Freedman, Vicki A., & Bianchi, Suzanne M. (2016). Gender, time use, and aging. Handbook of aging and the social sciences (pp. 163–180). Academic Press.

Solé-Auró, A., & Alcañiz, M. (2016). Educational attainment, gender and health inequalities among older adults in Catalonia (Spain). International Journal for Equity in Health, 15(1), 1–12

Stewart, J. (2013). Tobit or not Tobit? Journal of Economic and Social Measurement, 38(3), 263–290

Sullivan, O., & Gershuny, J. (2001). Cross-national changes in time-use: Some sociological (hi) stories re-examined. The British Journal of Sociology, 52(2), 331–347

Sullivan, O., Gershuny, J., & Robinson, J. P. (2018). Stalled or uneven gender revolution? A long-term processual framework for understanding why change is slow. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 10(1), 263–279

Thompson, M. N., & Dahling, J. J. (2019). Employment and poverty: Why work matters in understanding poverty. American Psychologist, 74(6), 673

Tsai, C.-T.L. (2006). The influence of Confucianism on women’s leisure in Taiwan. Leisure Studies, 25(4), 469–476

Van der Lippe, T., De Ruijter, J., De Ruijter, E., & Raub, W. (2011). Persistent inequalities in time use between men and women: A detailed look at the influence of economic circumstances, policies, and culture. European Sociological Review, 27(2), 164–179

Walker, A. (2002). A strategy for active ageing. International Social Security Review, 55(1), 121–139

World Bank. (2015). Live long and prosper: Aging in East Asia and Pacific (English). Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/832271468184782307/Live-long-and-prosper-aging-in-East-Asia-and-Pacific

Wu, Y.-T., Daskalopoulou, C., Terrera, G. M., Niubo, A. S., Rodríguez-Artalejo, F., Ayuso-Mateos, J. L., Bobak, M., Caballero, F. F., Fuente, J. de la, Torre-Luque, A. de la, García-Esquinas, E., Haro, J. M., Koskinen, S., Koupil, I., Leonardi, M., Pajak, A., Panagiotakos, D., Stefler, D., Tobias-Adamczyk, B., et al. (2020). Education and wealth inequalities in healthy ageing in eight harmonised cohorts in the ATHLOS consortium: A population-based study. The Lancet Public Health, 5(7), e386–e394

Yasuda, T., Iwai, N., Chin-Chun, Y., & Guihua, X. (2011). Intergenerational coresidence in China, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan: Comparative analyses based on the East Asian social survey 2006. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 42(5), 703–722

Yeh, C.-Y., Cheng, H., & Shi, S.-J. (2020). Public–private pension mixes in East Asia: Institutional diversity and policy implications for old-age security. Ageing and Society, 40(3), 604–625

Yerkes, M. A., Roeters, A., & Baxter, J. (2020). Gender differences in the quality of leisure: A cross-national comparison. Community, Work and Family, 23(4), 367–384

Zajacova, A., & Lawrence, E. M. (2018). The relationship between education and health: Reducing disparities through a contextual approach. Annual Review of Public Health, 39(1), 273–289

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the European Research Council Consolidator Grant agreement No 771736 (awardee: Man-Yee Kan), and the Economic and Social Research Council grant No ES/S014098/1 (awardee: Man-Yee Kan).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

First author is the principal investigator of the project. Data harmonization (a, b, d, e, g). Literature Review (all authors). Data analysis (b, c, d, f). Writing of: Introduction (a, c), Methods (a, b, c), Findings (a, b, c), Discussion (a, c). Revision (a, b, c, f, g). All authors read and agreed on the final draft of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This project has passed ethnic review checks.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

All authors read and agreed on the final draft of the paper.

Conflicts of interests

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kan, MY., Zhou, M., Negraia, D.V. et al. How do Older Adults Spend Their Time? Gender Gaps and Educational Gradients in Time Use in East Asian and Western Countries. Population Ageing 14, 537–562 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-021-09345-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-021-09345-3