Abstract

Dyskinesia induced by L-DOPA administration (LID) is one of the most invalidating adverse effects of the gold standard treatment restoring dopamine transmission in Parkinson’s disease (PD). However, LID manifestation in parkinsonian patients is variable and heterogeneous. Here, we performed a candidate genetic pathway analysis of the mTOR signaling cascade to elucidate a potential genetic contribution to LID susceptibility, since mTOR inhibition ameliorates LID in PD animal models. We screened 64 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) mapping to 57 genes of the mTOR pathway in a retrospective cohort of 401 PD cases treated with L-DOPA (70 PD with moderate/severe LID and 331 with no/mild LID). We performed classic allelic, genotypic, and epistatic analyses to evaluate the association of individual or combinations of SNPs with LID onset and with LID severity after initiation of L-DOPA treatment. As for the time to LID onset, we found significant associations with SNP rs1043098 in the EIF4EBP2 gene and also with an epistatic interaction involving EIF4EBP2 rs1043098, RICTOR rs2043112, and PRKCA rs4790904. For LID severity, we found significant association with HRAS rs12628 and PRKN rs1801582 and also with a four-loci epistatic combination involving RPS6KB1 rs1292034, HRAS rs12628, RPS6KA2 rs6456121, and FCHSD1 rs456998. These findings indicate that the mTOR pathway contributes genetically to LID susceptibility. Our study could help to identify the most susceptible PD patients to L-DOPA in order to prevent the appearance of early and/or severe LID in a future. This information could also be used to stratify PD patients in clinical trials in a more accurate way.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- 6-OHDA:

-

6-Hydroxydopamine

- DA:

-

Dopamine

- LID:

-

L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia

- mAF:

-

Minor allele frequency

- MDR:

-

Multifactorial dimensionality reduction

- mTORC:

-

Mechanistic target of rapamycin complex

- PD:

-

Parkinson’s disease

- SNPs:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

- TTD:

-

Time to dyskinesia

- TTL:

-

Time to L-DOPA

- TLP:

-

Time to LID Peak

- LED:

-

L-DOPA equivalent dose

References

Fahn S (1998) Medical treatment of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol 245:P15–P24

Fahn S (2008) Clinical aspects of Parkinson disease. In: Parkinson’s disease, 1st edn. Academic Press, New York, p 1–8

Cotzias GC, Papavasiliou PS, Gellene R (1969) Modification of parkinsonism—chronic treatment with L-Dopa. N Engl J Med 280:337–345. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM196902132800701

Bastide MF, Meissner WG, Picconi B, Fasano S, Fernagut PO, Feyder M, Francardo V, Alcacer C et al (2015) Pathophysiology of L-dopa-induced motor and non-motor complications in Parkinson’s disease. Prog Neurobiol 132:96–168

Chondrogiorgi M, Tatsioni A, Reichmann H, Konitsiotis S (2014) Dopamine agonist monotherapy in Parkinson’s disease and potential risk factors for dyskinesia: a meta-analysis of levodopa-controlled trials. Eur J Neurol 21:433–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.12318

Jankovic J (2005) Motor fluctuations and dyskinesias in Parkinson’s disease: clinical manifestations. Mov Disord 20:S11–S16. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.20458

Nadjar A, Gerfen CR, Bezard E (2009) Priming for l-dopa-induced dyskinesia in Parkinson’s disease: a feature inherent to the treatment or the disease? Prog Neurobiol 87:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.09.013

Malagelada C, Ryu EJ, Biswas SC, Jackson-Lewis V, Greene LA (2006) RTP801 is elevated in Parkinson brain substantia nigral neurons and mediates death in cellular models of Parkinson’s disease by a mechanism involving mammalian target of rapamycin inactivation. J Neurosci 26:9996–10005. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3292-06.2006

Sarkar S, Ravikumar B, Floto RA, Rubinsztein DC (2009) Rapamycin and mTOR-independent autophagy inducers ameliorate toxicity of polyglutamine-expanded huntingtin and related proteinopathies. Cell Death Differ 16:46–56. https://doi.org/10.1038/cdd.2008.110

Tain LS, Mortiboys H, Tao RN et al (2009) Rapamycin activation of 4E-BP prevents parkinsonian dopaminergic neuron loss. Nat Neurosci 12:1129–1135. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2372

Kim DH, Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, King JE, Latek RR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Sabatini DM (2002) mTOR interacts with raptor to form a nutrient-sensitive complex that signals to the cell growth machinery. Cell 110:163–175

Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM (2005) Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science (80- ) 307:1098–1101. https://doi.org/10.1126/Science1106148

Calabresi P, Galletti F, Saggese E, Ghiglieri V, Picconi B (2007) Neuronal networks and synaptic plasticity in Parkinson’s disease: beyond motor deficits. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 13(Suppl 3):S259–S262. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1353-8020(08)70013-0

Bockaert J, Marin P (2015) mTOR in brain physiology and pathologies. Physiol Rev 95:1157–1187

Laplante M, Sabatini DM (2012) mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell 149:274–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017

Malagelada C, Jin ZH, Jackson-Lewis V, Przedborski S, Greene LA (2010) Rapamycin protects against neuron death in in vitro and in vivo models of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci 30:1166–1175. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3944-09.2010

Santini E, Heiman M, Greengard P, Valjent E, Fisone G (2009) Inhibition of mTOR signaling in Parkinson’s disease prevents L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia. Sci Signal 2:ra36. https://doi.org/10.1126/scisignal.2000308

Decressac M, Bjorklund A (2013) mTOR inhibition alleviates L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia in parkinsonian rats. J Parkinsons Dis 3:13–17. https://doi.org/10.3233/JPD-120155

Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Blankson S, Lees AJ (1993) A clinicopathologic study of 100 cases of Parkinson’s disease. Arch Neurol 50:140–148

Dickson DW, Braak H, Duda JE, Duyckaerts C, Gasser T, Halliday GM, Hardy J, Leverenz JB et al (2009) Neuropathological assessment of Parkinson’s disease: Refining the diagnostic criteria. Lancet Neurol 8:1150–1157

Fahn S, Elton R (1987) Unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale. In: Recent developments in Parkinson’s disease, 2nd edn. Macmillan Healthcare Information, Florham Park, p 153–163

Fernández-Santiago R, Iranzo A, Gaig C, Serradell M, Fernández M, Tolosa E, Santamaría J, Ezquerra M (2016) Absence of LRRK2 mutations in a cohort of patients with idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder. Neurology 86:1072–1073. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000002304

Sole X, Guino E, Valls J, Iniesta R, Moreno V (2006) SNPStats: a web tool for the analysis of association studies. Bioinformatics 22:1928–1929. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btl268

Ritchie M, Hahn L, Roodi N et al (2001) Multifactor-dimensionality reduction reveals high-order interactions among estrogen-metabolism genes in sporadic breast cancer. Am J Hum Genet 69:138–147. https://doi.org/10.1086/321276

Motsinger AA, Ritchie MD (2006) The effect of reduction in cross-validation intervals on the performance of multifactor dimensionality reduction. Genet Epidemiol 30:546–555. https://doi.org/10.1002/gepi.20166

Reijmerink NE, Bottema RWB, Kerkhof M, Gerritsen J, Stelma FF, Thijs C, van Schayck CP, Smit HA et al (2010) TLR-related pathway analysis: novel gene-gene interactions in the development of asthma and atopy. Allergy 65:199–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02111.x

Shen Y, Xun G, Guo H, He Y, Ou J, Dong H, Xia K, Zhao J (2016) Association and gene-gene interactions study of reelin signaling pathway related genes with autism in the Han Chinese population. Autism Res 9:436–442. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1540

Holmans P, Moskvina V, Jones L, Sharma M, The International Parkinson's Disease Genomics Consortium (IPDGC), Vedernikov A, Buchel F, Sadd M et al (2013) A pathway-based analysis provides additional support for an immune-related genetic susceptibility to Parkinson’s disease. Hum Mol Genet 22:1039–1049. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/dds492

Mas S, Gassó P, Ritter MA, Malagelada C, Bernardo M, Lafuente A (2015) Pharmacogenetic predictor of extrapyramidal symptoms induced by antipsychotics: Multilocus interaction in the mTOR pathway. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 25:51–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.11.011

Zai CC, Tiwari AK, Mazzoco M, de Luca V, Müller DJ, Shaikh SA, Lohoff FW, Freeman N et al (2013) Association study of the vesicular monoamine transporter gene SLC18A2 with tardive dyskinesia. J Psychiatr Res 47:1760–1765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.07.025

Comi C, Ferrari M, Marino F, Magistrelli L, Cantello R, Riboldazzi G, Bianchi M, Bono G et al (2017) Polymorphisms of dopamine receptor genes and risk of L-Dopa-induced dyskinesia in Parkinson’s disease. Int J Mol Sci 18:242. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18020242

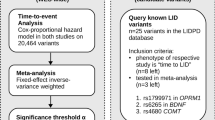

Cheshire P, Bertram K, Ling H, O'Sullivan SS, Halliday G, McLean C, Bras J, Foltynie T et al (2014) Influence of single nucleotide polymorphisms in COMT, MAO-A and BDNF genes on dyskinesias and levodopa use in Parkinson’s disease. Neurodegener Dis 13:24–28. https://doi.org/10.1159/000351097

Devos D, Lejeune S, Cormier-Dequaire F, Tahiri K, Charbonnier-Beaupel F, Rouaix N, Duhamel A, Sablonnière B et al (2014) Dopa-decarboxylase gene polymorphisms affect the motor response to l-dopa in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 20:170–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2013.10.017

Kaplan N, Vituri A, Korczyn AD, Cohen OS, Inzelberg R, Yahalom G, Kozlova E, Milgrom R et al (2014) Sequence variants in SLC6A3, DRD2, and BDNF genes and time to levodopa-induced dyskinesias in Parkinson’s disease. J Mol Neurosci 53:183–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12031-014-0276-9

Polakiewicz RD, Schieferl SM, Gingras AC, Sonenberg N, Comb MJ (1998) ?-opioid receptor activates signaling pathways implicated in cell survival and translational control. J Biol Chem 273:23534–23541. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.273.36.23534

Picconi B, Centonze D, Håkansson K, Bernardi G, Greengard P, Fisone G, Cenci MA, Calabresi P (2003) Loss of bidirectional striatal synaptic plasticity in L-DOPA–induced dyskinesia. Nat Neurosci 6:501–506. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn1040

Grünblatt E, Mandel S, Jacob-Hirsch J et al (2004) Gene expression profiling of parkinsonian substantia nigra pars compacta; alterations in ubiquitin-proteasome, heat shock protein, iron and oxidative stress regulated proteins, cell adhesion/cellular matrix and vesicle trafficking genes. J Neural Transm 111:1543–1573. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-004-0212-1

Banko JL (2005) The translation repressor 4E-BP2 is critical for eIF4F complex formation, synaptic plasticity, and memory in the hippocampus. J Neurosci 25:9581–9590. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2423-05.2005

Zhang Y, Meredith GE, Mendoza-Elias N, Rademacher DJ, Tseng KY, Steece-Collier K (2013) Aberrant restoration of spines and their synapses in L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia: involvement of corticostriatal but not thalamostriatal synapses. J Neurosci 33:11655–11667. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0288-13.2013

Mandel SA, Youdim MBH, Riederer P, et al (2013) Peripheral blood gene markers for early diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. (Patent reference number: US20130217028A1) Google Patents web. https://patents.google.com/patent/US20130217028. Accessed 26 October 2010

Charbonnier-Beaupel F, Malerbi M, Alcacer C, Tahiri K, Carpentier W, Wang C, During M, Xu D et al (2015) Gene expression analyses identify Narp contribution in the development of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia. J Neurosci 35:96–111. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5231-13.2015

Angliker N, Rüegg MA (2013) In vivo evidence for mTORC2-mediated actin cytoskeleton rearrangement in neurons. Bioarchitecture 3:113–118. https://doi.org/10.4161/bioa.26497

Jacinto E, Loewith R, Schmidt A et al (2004) Mammalian TOR complex 2 controls the actin cytoskeleton and is rapamycin insensitive. Nat Cell Biol 6:1122–1128. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb1183

Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Kim DH et al (2004) Rictor, a novel binding partner of mTOR, defines a rapamycin-insensitive and raptor-independent pathway that regulates the cytoskeleton. Curr Biol 14:1296–1302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.054

Rodriguez-Viciana P, Warne PH, Dhand R, Vanhaesebroeck B, Gout I, Fry MJ, Waterfield MD, Downward J (1994) Phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase direct target of Ras. Nature 370:527–532. https://doi.org/10.1038/370527a0

Pacold ME, Suire S, Perisic O, Lara-Gonzalez S, Davis CT, Walker EH, Hawkins PT, Stephens L et al (2000) Crystal structure and functional analysis of Ras binding to its effector phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma. Cell 103:931–943

Kitada T, Asakawa S, Hattori N, Matsumine H, Yamamura Y, Minoshima S, Yokochi M, Mizuno Y et al (1998) Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. Nature 392:605–608. https://doi.org/10.1038/33416

Petrucelli L, O’Farrell C, Lockhart PJ et al (2002) Parkin protects against the toxicity associated with mutant alpha-synuclein: proteasome dysfunction selectively affects catecholaminergic neurons. Neuron 36:1007–1019

Helton TD, Otsuka T, Lee MC et al (2008) Pruning and loss of excitatory synapses by the parkin ubiquitin ligase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:19492–19497. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0802280105

Wang L, Gout I, Proud CG (2001) Cross-talk between the ERK and p70 S6 kinase (S6K) signaling pathways: MEK-dependent activation of S6K2 in cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem 276:32670–32677. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M102776200

Pardo OE, Seckl MJ (2013) S6K2: The neglected S6 kinase family member. Front Oncol 3:191. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2013.00191

Shahbazian D, Roux PP, Mieulet V, Cohen MS, Raught B, Taunton J, Hershey JWB, Blenis J et al (2006) The mTOR/PI3K and MAPK pathways converge on eIF4B to control its phosphorylation and activity. EMBO J 25:2781–2791. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.emboj.7601166

Cao H, Yin X, Cao Y, Jin Y, Wang S, Kong Y, Chen Y, Gao J et al (2013) FCHSD1 and FCHSD2 are expressed in hair cell stereocilia and cuticular plate and regulate actin polymerization in vitro. PLoS One 8:e56516. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056516

Coyle IP, Koh YH, Lee WCM, Slind J, Fergestad T, Littleton JT, Ganetzky B (2004) Nervous wreck, an SH3 adaptor protein that interacts with Wsp, regulates synaptic growth in Drosophila. Neuron 41:521–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0896-6273(04)00016-9

Huang RS, Duan S, Shukla SJ, Kistner EO, Clark TA, Chen TX, Schweitzer AC, Blume JE et al (2007) Identification of genetic variants contributing to cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity by use of a genomewide approach. Am J Hum Genet 81:427–437. https://doi.org/10.1086/519850

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Jason H. Moore and Dr. Peter Andrews for their kind assessment with the MDR software use and helpful discussion. We also thank Dr. Roger Anglada from the Genomics Core Facility from the Universitat Pompeu Fabra (Barcelona) for his work and helpful assessment with sample analysis. We acknowledge the CERCA Program from the Generalitat de Catalunya and the FEDER Program from the European Union to IDIBAPS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Author notes

N.M-F & R.F-S. contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All subjects were recruited at the Movement Disorders Unit from the Hospital Clínic Provincial de Barcelona. Written informed consent and whole blood samples were obtained from each subject. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona.

Conflict of Interest

This work has been granted by the Michael J. Fox Foundation, Dyskinesia Challenge 2014. The technology derived from this work has been filed for a European patent application (File number: EP17382248), to develop a diagnostics method of personalized medicine for PD patients.

Electronic supplementary material

Figure 1

Illustration of the mTOR pathway with the proteins encoded by the genes with the selected SNPs for the analyses. The illustration contains 64 proteins directly or closely related to the mTOR pathway. For the analyses, SNPs from the genes coding for these proteins were selected. (PNG 8102 kb)

Figure 2

Association of the SNPs rs1043098 in EIF4EBP2, rs2043112 in RICTOR and rs4790904 in PRKCA genes with LID onset. (A) SNP interaction map with LID onset. The nodes were obtained in the epistatic analyses with the MDR software and represent the polymorphisms, including the genes that contain the SNP, while the numeric values inside represent the main information gain. The links show the interaction between SNPs. The color of the lines indicates the type of interaction explaining synergy or redundancy (yellow = independency, blue = correlation and orange = synergistic relationship). (B) Localization in the mTOR pathway of the proteins translated from the genes with SNPs significantly associated with LID onset. In color are highlighted the proteins 4EBP2 (orange), Rictor (pink) and PKCα (green) that are the product of the genes EIF4EBP2, RICTOR and PRKCA, respectively. (PNG 791 kb)

Figure 3

Distribution of high-risk and low-risk genotypes in the interaction of rs1043098 in EIF4EBP2, rs2043112 in RICTOR and rs4790904 in PRKCA with LID onset. Light gray boxes present combinations for early LID onset and dark gray boxes present the combinations for late LID onset. In each cell is shown the TTD average (7,62 years) in a horizontal line and in vertical the difference in years in each combination from the global mean. (PNG 23.5 kb)

Figure 4

Association of the SNPs rs12628 in HRAS, rs5456121 in RPS6KA2, rs1292034 in RPS6KB1 and rs456998 in FCHSD1 genes with LID severity. (A) SNP interaction map with LID onset. The nodes were obtained in the epistatic analyses with the MDR software and represent the polymorphisms, including the gene that contain the SNP, while the numeric values inside represent the main information gain. The links show the interaction between SNPs. The color of the lines indicates the type of interaction explaining synergy or redundancy (yellow = independency, blue = correlation and orange = synergistic relationship). (B) Localization in the mTOR pathway of the proteins translated from the genes with SNPs significantly associated with LID severity. In color are highlighted the proteins H-Ras (light blue), ribosomal protein S6 kinase beta-1, S6 K1, and ribosomal protein S6 kinase alpha-2, S6 K2, (green and pink) and FCHSD1 (red) that are encoded by the genes HRAS, RPS6KB1, RPS6KA2 and FCHSD1, respectively. (PNG 851 kb)

Figure 5

Distribution of high-risk and low-risk genotypes in the interaction of rs1292034 in RPS6KB1, rs12628 in HRAS, rs6456121 in RPS6KA2 and rs456998 in FCHSD1 with LID severity. Dark gray boxes present the high-risk factor combinations (moderate/severe LID severity) and light gray boxes present the low risk factor combinations (no/mild LID severity). Each cell shows the number of PD patients with moderate/severe LID with that specific genotype on the left bar and control group with no/mild LID on the right bar. (PNG 53.4 kb)

ESM 1

SNPs in the genes of the mTOR pathway and PD related genes selected for the analyses. (DOCX 22.9 kb)

ESM 2

Distribution of genotypes in the interaction of rs1043098 in EIF4EBP2, rs2043112 in RICTOR and rs4790904 in PRKCA with LID onset. (DOCX 18.6 kb)

ESM 3

MDR analysis of SNP-SNP interaction with LID severity considering no LID as the control group. (DOCX 15.3 kb)

ESM 4

Distribution of genotypes in the interaction of rs1292034 in RPS6KB1, rs12628 in HRAS, rs6456121 in RPS6KA2 and rs456998 in FCHSD1 with LID severity. (DOCX 23.1 kb)

ESM 5

MDR forced analysis for the interaction between rs1292034 RPS6KB1, rs12628 HRAS, rs6456121 RPS6KA2 and rs456998 FCHSD1 with LID with severity as main variable. (DOCX 16.9 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Martín-Flores, N., Fernández-Santiago, R., Antonelli, F. et al. MTOR Pathway-Based Discovery of Genetic Susceptibility to L-DOPA-Induced Dyskinesia in Parkinson’s Disease Patients. Mol Neurobiol 56, 2092–2100 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-018-1219-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-018-1219-1