Abstract

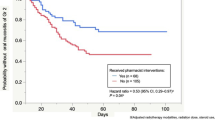

Oral therapies have highly modified cancer patient management and changed hospital practises. We introduce a specific Oral Therapy Centre and retrospectively review information prospectively recorded by co-ordination nurses (CNs) (the DICTO programme). We describe the roles played by CNs in the management of oral cancer therapies at Limoges Dupuytren Hospital between May 2015 and June 2018. All cancers, irrespective of stage or whether oral general chemotherapy or targeted therapy was prescribed, are included. We followed up 287 patients of median age 67 years (range 26–89 years). Of these, 76% had metastases and 44% were on first-line therapy. The vast majority (88%) of their first CN contacts occurred just after physician consultation and lasted an average of 60 min. As part of follow-up, the CNs made 2719 calls (average 10 min) to patients to educate them and to verify compliance and drug tolerance. They also received 833 calls from patients (70%) or their relatives or health professionals (30%) seeking advice on management of side effects. In addition to the initial appointments, 1069 non-scheduled follow-up visits were made to assess side effects (49.2%). The CNs devoted 5 h to each patient over 3 months of treatment (i.e. 25 min/day) and, also organised scheduled hospitalisations in the department of oncology for 51% of patients. We show the interest and real-life work in a specific oral therapy centre within oncology department with the role of CNs to facilitate the global health care of the patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recent developments in oral chemotherapy and targeted therapies have radically changed cancer patient management; ambulatory care is now common. Oral therapies afford many advantages, improving patient quality of life and autonomy by reducing hospital stays and involving patients in their own care [1, 2]. During oral treatment, early detection of adverse events avoids emergency hospitalisation, and non-adherence to/discontinuation of treatment [3]. Although patients prefer oral to intravenous therapy [4, 5], non-adherence may become an issue because patients are not constantly supervised [6]. Multidisciplinary care is required to follow this therapy. Healthcare organisations must prioritise coordination to ensure the quality and safety of patient care [7, 8]. Optimising the care of cancer patients at home requires the co-ordinated intervention of hospital and town healthcare professionals to detect, prevent, and manage adverse events, avoid drug interactions, and educate patients. Several studies have revealed the benefits of managing patients treated on oral cancer drugs, both in terms of improved adherence and reduced toxicity. Usually, nurses are involved in patient contact, sometimes via telephone or other forms of communication [9,10,11,12].

The 2014–2019 cancer plan emphasises the need to re-organise care delivery, to strengthen town-hospital links, and to train medical and paramedical professionals [13]. Currently, no standard of care for cancer patients on oral therapy exists; few programmes treat a wide spectrum of cancers or involve all healthcare professionals [14]. To improve co-ordination of oral anti-cancer treatments, University Limoges Hospital developed a specific centre featuring strong links between physicians, nurses, and pharmacists of the hospital and town. In 2010, Limoges Hospital became 1 of 35 hospitals selected to develop a personalised approach to cancer treatment (the PICSCEL project) [15]. This highlighted the needs of certain patients in terms of care co-ordination between the town and hospital. In 2014, we were asked to develop a new centre to follow-up cancer patients on oral therapy and to link town and hospital healthcare professionals. The centre is an integral part of our Department of Medical Oncology. Here, we describe the centre’s operations with a focus on the roles played by co-ordinating nurses (CNs) (within the DICTO programme) who prospectively recorded their work and the tools used.

Patients and methods

This was a single-centre prospective study of the roles played by CNs in the management of cancer patients on oral therapy prescribed by the Limoges Dupuytren Hospital. We included all cancer patients (metastatic or not) on oral chemotherapy and/or targeted therapy, at the request of the referring doctors, managed from May 2015 to June 2018.

Objectives

We describe the work of the CNs. We explain their roles in detail, the contributions made, the added value of their care, and communications between hospital and non-hospital health professionals.

Eligibility criteria

The oncologists proposed the DICTO programme to patients commencing oral therapy. The eligibility criteria were fluency in French, age 18 years or older, a diagnosis of a solid tumour requiring oral chemotherapy or targeted therapy, a willingness to be followed up, and a telephone at home. The exclusion criteria were hormonotherapy alone, no home telephone, inclusion in a clinical trial, a previous treatment with oral drugs, or a need for combined oral and intravenous treatments. Patients on multiple oral therapies were included. Patients were censored on death, disease progression requiring initiation of intravenous treatment, or on request.

Organisation of the oral therapy centre (OTC)

The OTC is a dedicated unit in the Department of Medical Oncology, with a consultation room and a nursing office. A dedicated hotline facilitates communication between CNs, patients, their family members, and other healthcare professionals. The hotline is open from Monday to Friday from 10 am to 6 pm. The OTC includes oncologist practitioners, CNs trained in the management of oral treatments, health professionals offering supportive care, pharmacists, and a social worker. The six CNs have been trained in oral therapy oncology management. One or two CNs are assigned to OTC daily to follow-up patients. The CNs also arrange consultations with doctors when necessary. When patients visit, pharmacy consultations are also offered to adapt treatments (if necessary), monitor side effects, and explore patient attitudes.

Procedure at initial consultation

After the patient consulted with the oncologist and oral treatment was prescribed, the CNs assumed responsibility for patient care. Twenty-four oral chemotherapies and targeted therapies were delivered (Supplementary Table 1). For each drug, the CNs had been trained, and had information sheets on how to deal with: biology (essential blood tests), telephone intervals (and modifications thereof if patients visited for blood tests), medical consult intervals, monitoring of specific toxicities, and when to call the referring doctor.

The CNs had been trained to deal with each type of medication, had information sheets on how to take essential blood tests into account, establish the intervals for medical consultations, monitor specific toxicities and determine when to call the referring doctors.

The CNs explained to the patients (and their families, if possible) drug indications, dosages, administration, adverse reactions, and drug interactions. During initial appointments, CNs gave patients drug data and follow-up notebooks, finalised personalised care plans, assessed social precariousness and obtained G8 scores [16], contacted social services if social fragility was evident, ensured that the secretariat sent letters and drug data to general practitioners, explained the prescriptions, called home nurses and town pharmacists and sent all necessary documents, and programmed medical consults.

We identified high-risk situations at initial consultation and special attention (extra telephone calls and systematic social and psychological support) was given to these patients. It included patients with brain tumours, pancreatic cancers, or head-and-neck cancers (because of poor prognoses or a high risk for a complex short- or long-term disease course); with metastases or inoperable local recurrences; over 75 years of age; and at risk for social fragility as revealed by the INCA indicators [17]. The INCA social fragility indicators are over 75 years of age, living alone, disability, difficulty speaking French, difficult financial situation, and difficulty performing daily activities. A patient might exhibit several risk factors.

Follow-up

All patients were followed up throughout their treatments via telephone and consultations. Follow-up was individualised by the type of drug and patient characteristics (based on questionnaire responses) and formalised in written or computerised notes held in the OTC. All questionnaires were developed and validated by a working group composed of doctors, nurses, and pharmacists [18]. Phone calls were made on days 15 and 30, and then every 3 months. An additional call for high-risk patients was made between day 8 and 10. During each call, the CN assessed compliance and drug tolerance, educated the patient, answered questions, reinforced the initial advice, and planned the next visit or telephone call.

CNs contacted local nurses, general practitioners, local pharmacists, or paramedical staff, depending on the patient’s situation. Hospitalisation was discussed with the oncologists who prescribed the drugs. If hospitalisation was necessary, the CNs recorded why and the outcomes of treatment. The CNs actively facilitated the patient’s return home by calling all town caregivers. All direct or indirect actions were recorded on a computer spreadsheet.

Clinical data were collected in accordance with French bioethics laws addressing patient information and consent. This project has been ethically approved by the relevant national authority: the National Institute of Cancer (INCa) and the Ministry of Health (no. DGOS/R3/2014/235–24 July 2014). Patients provided written (signed) informed consent to use their medical and administrative data.

Statistical analyses

All data were collected and analysed using STATVIEW software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Quantitative data are given as medians ± standard deviations (SDs) and qualitative results are numbers with percentages. The significance of between-group differences was evaluated using the Chi-square test. Means were compared using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test for continuous variables and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for categorical variables. A p-value < 0.05 was taken to reflect significance.

Results

Patient population

Of 436 patients on oral treatments, 287 were recruited between May 2015 and June 2018 (Fig. 1). Demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. We included 155 females and 132 males of median age 67 years (range 26–89 years); 63 were older than 75 years (Supplementary Fig. 1). Most patients lived in Limousin (Haute-Vienne, Creuse, Corrèze) (74%); the others lived in neighbouring areas or sometimes in more distant places (Supplementary Fig. 2). The sites of primary cancer varied. The most common cancers were breast (30%), renal (19%), colorectal (12%), and brain cancers (10%) (Table 1). Most cancers were metastatic (76%); 67 patients were prescribed neoadjuvants. Most patients (131) were considered high-risk because of metastases. Other high-risk INCA indicators included age > 75 years (n = 63), social disadvantage (n = 36), and tumour type (n = 32) (these sometimes overlapped).

Treatment

The median time between the first diagnosis of cancer and oral therapy commencement was 23 months (1–286 months). Of patients with metastases, 98 (44%) were on first-line, 51 (24%) on second-line, and 71 (32%) on third- or later-line drugs (Table 1). Supplementary Table 1 lists the treatments; 68% were targeted (n = 15). Everolimus was most commonly prescribed (17.4%), followed by capecitabine (13.5%) and palbociclib (9.4%). Sunitinib and everolimus induced the most side effects (39% and 38%, respectively) followed by regorafenib (36%) and pazopanib (36%). Most participants developed disease progression requiring new intravenous treatment (48.4%), side effects (24%), or died (4%). No patients withdrew from the programme. The median treatment duration was 4 months (range 0–37 months) (Supplementary Table 1).

Management of patients by CNs

The first CN contact lasted for an average of 60 min (20–120 min) and usually occurred just after the patient visited the doctor (n = 255, 88%). The consultations were longer for patients older than 75 years (60 vs. 50 min, p = 0.01, respectively). Consultation length did not vary by other high-risk factors or the distance between the hospital and the patient’s home. Information sheets were given to all patients (except two who refused them). If a follow-up booklet was available, it was given to the patients (254; 88%). Personalised care was scheduled for 253 patients (88%) (Table 2). A questionnaire exploring satisfaction was completed by the first 30 patients; feedback was positive.

During follow-up, of the 2720 calls made by CNs, 1869 were to patients (66.3%) and 226 were to helpers and family members. Calls dealt with test results (926/1345; 68.8%), systematic follow-up (658/2719; 24.2%), and treatment validation (434/2719; 16.0%) (Table 3). CNs received 833 calls of median duration 10 min (2–135 min) from patients; 70% were calling from places distant from family members (Table 4). The calls explored management of side effects (226/334) and test data validating drug prescription (n = 84). Some patients complained of anxiety/a need for moral support (n = 71). Other calls dealt with misunderstandings/reformulations of plans (49/79; 62%) (Table 4). CN consultations in the OCT (median duration 30 min) were scheduled on 1,069 occasions. Of the 287 patients, 238 received a mean of 3 such consultations (range 1–18). Side effects were assessed during either non-scheduled (49.2%) or scheduled (50.8%) appointments (Table 5). Appointment numbers did not vary by patient geographic location or high-risk status. The CNs also provided follow-up care for patients after 248 hospitalisations (a median of 2 appointments per hospitalised patient [range 2–12 hospital stays]). Of all hospitalisations, 125 were in the department of oncology (scheduled, 51%), 81 were in the emergency department, and 23 were in other departments (unscheduled, 49%).

Town-hospital links created by CNs

At the first consultation, the CNs telephoned the patient’s general practitioner (88%), town nurse (65%), and town pharmacist (84%). The combined median duration of all calls was 20 min (range 2–65 min). Letters and booklets were sent to general practitioners (Table 2). Of patients at high INCA-defined risk, 46 were referred to social services during initial consultations; some refused or claimed that assistance was already in place. The CNs also contacted hospital nurses, dieticians, psychologists, town laboratories, and hospital doctors and, also requested additional examinations (n = 72) (Table 2).

During follow-up, CNs made threefold more calls than they received (2719 [median time 10 min; range 2–130 min] vs. 833). A total of 726 calls were to health professionals (Table 3) to discuss test results (419/1345 tests; 31%) and administrative data (67/168 datasets; 40%), and to seek medical information (44/74 questions; 60%). CNs made unplanned calls to doctors if decisions lay outside CN competence (60%) and to order prescriptions (16%) (Table 3). The number of calls did not vary by patient geographic home or risk status (low or high). Of the 833 unplanned calls received by CNs, 96 were from concerned health professionals who discussed toxicities (32/334; 9.5%), misunderstandings/reformulations (19/79; 24%), and administrative details (16/59; 27%) (Table 4).

In conclusion, overall, the CNs devoted 5 h to each patient over 3 months, including calls and consultations. A total of 1847 calls were unplanned, related to patient requests or actions required following planned calls.

Discussion

The use of oral therapies in oncology has increased over the past decade, necessitating changes in the monitoring of side effects; this is essential to ensure patient compliance, assess safety, and optimise therapy. Here, we describe the pivotal roles played by the CNs of a multidisciplinary OTC team. The CNs optimised communications between patients and healthcare professionals. The CNs of the OTC involved outside healthcare professionals in patient care irrespective of cancer or drug type. To the best of our knowledge, few organisations have used CNs, and hospital and town pharmacists and doctors, to manage oral therapies for all types of cancer patients [19]. Interventions included education, monitoring, administration, telephone calls, and physical assessments; high-risk patients often do not receive so much attention [19]. No patients withdrew and the rate of side effects was low (24%); the OTC worked well. Full-time CNs are required to adequately co-ordinate town and hospital healthcare professionals. The call register showed that not only patients, but also their families, needed to contact the OTC. One or two nurses were always available to take calls and then to alert the necessary professionals. Certain drugs associated with serious side effects (e.g. everolimus) were specifically monitored [20] reducing treatment discontinuation [21]. When published, the outcomes of CAPRI, a rare randomised controlled trial enrolling breast cancer patients, are expected to confirm the critical roles played by nurse “navigators” and a Web portal in terms of co-ordinating town and hospital carers during routine delivery of oral anti-cancer therapy [12].

Although patients prefer oral drugs, and although out-patient chemotherapy improves the quality of life [22], management of anxiety experienced by patients and their families remains a major issue [2, 23, 24]. Some anxiety is attributable to side effects; patients on oral therapy are not monitored to the same extent as those on intravenous therapy [2, 23, 24].We found that 37.8% of calls received concerned side effects (the prime reason for calling). It is essential to manage treatment, improve patient quality of life, and provide psychological assistance. Whether via the telephone or otherwise, patients must have information [25, 26].

A co-ordinated regional health network of the Ile de France (CHIMORAL) has reported findings [14]. The hospitalisation rates of orally and intravenously treated cancer patients did not differ. Patients reporting satisfaction with treatment and minimal anxiety adhered well to oral chemotherapy [1]. We thus evaluated patient quality of life. The CNs reduced emergency admissions and physician visits, and thus were cost-effective, although further prospective studies are required [27]. A novel feature of our work is that we included pharmacists when co-ordinating patient management. A prospective study involving 18 French cancer centres found that only 54.5% had deployed oral anti-cancer drugs programmes that involved pharmacists, and only 44.4% featured hospital/community co-ordination [28]. Community pharmacists educate patients but also require cancer-specific education [29, 30]. Calls from nurses to general practitioners are very well accepted if the nurses are trained in oral cancer treatment. A possible limitation of our work is that we included all types of cancers and treatments, but we deliberately chose to analyse the entire population, because in the real world, our oncology department is responsible for a very large area. Another limitation is that we sought feedback from only the first 30 patients, and we did not survey hospital and town healthcare professionals.

In conclusion, we developed and implemented a new healthcare structure for cancer patients on oral therapy; all patients received personalised support throughout their treatment. Our OTC co-ordinated all hospital and town professionals who “surrounded” the patient. The OTC improves patient quality of life, reduces anxiety, and improves compliance.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Jacobs JM, Pensak NA, Sporn NJ, MacDonald JJ, Lennes IT, Safren SA, et al. Treatment satisfaction and adherence to oral chemotherapy in patients with cancer. JOP. 2017;13:e474–e485485.

Jacobs JM, Ream ME, Pensak N, Nisotel LE, Fishbein JN, MacDonald JJ, et al. Patient experiences with oral chemotherapy: adherence, symptoms, and quality of life. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2019;17:221–8.

Palmer DH, Johnson PJ. Evaluating the role of treatment-related toxicities in the challenges facing targeted therapies for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2015;34:497–509.

Liu G, Franssen E, Fitch MI, Warner E. Patient preferences for oral versus intravenous palliative chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:110–5.

Twelves C, Gollins S, Grieve R, Samuel L. A randomised cross-over trial comparing patient preference for oral capecitabine and 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin regimens in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:239–45.

Bassan F, Peter F, Houbre B, Brennstuhl MJ, Costantini M, Speyer E, et al. Adherence to oral antineoplastic agents by cancer patients: definition and literature review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2014;23:22–35.

Holle LM, Puri S, Clement JM. Physician-pharmacist collaboration for oral chemotherapy monitoring: Insights from an academic genitourinary oncology practice. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2016;22:511–6.

Schneider SM, Hess K, Gosselin T. Interventions to promote adherence with oral agents. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2011;27:133–41.

Bordonaro S, Romano F, Lanteri E, Cappuccio F, Indorato R, Butera A, et al. Effect of a structured, active, home-based cancer-treatment program for the management of patients on oral chemotherapy. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8:917–23.

Cnossen IC, van Uden-Kraan CF, Eerenstein SEJ, Jansen F, Witte BI, Lacko M, et al. An online self-care education program to support patients after total laryngectomy: feasibility and satisfaction. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:1261–8.

Craven O, Hughes CA, Burton A, Saunders MP, Molassiotis A. Is a nurse-led telephone intervention a viable alternative to nurse-led home care and standard care for patients receiving oral capecitabine? Results from a large prospective audit in patients with colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer Care. 2013;22:413–9.

Gervès-Pinquié C, Daumas-Yatim F, Lalloué B, Girault A, Ferrua M, Fourcade A, et al. Impacts of a navigation program based on health information technology for patients receiving oral anticancer therapy: the CAPRI randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:133.

Plan cancer 2014–2019 : priorités et objectifs - Plan cancer. 2015. https://www.e-cancer.fr/Plan-cancer/Plan-cancer-2014-2019-priorites-et-objectifs. Accessed 29 Feb 2020.

Maritaz C, Gault N, Roy C, Tubach F, Burnel S, Lotz J-P. Impact of a coordinated regional organization to secure the management of patients on oral anticancer drugs: CHIMORAL, a comparative trial. Bull Cancer. 2019;106:734–46.

Résultats des expérimentations du parcours personnalisé des patients pendant et après le cancer. Rapport d’évaluation - Ref : BILEVALPPAC12. 2012. https://www.e-cancer.fr/Expertises-et-publications/Catalogue-des-publications/Resultats-des-experimentations-du-parcours-personnalise-des-patients-pendant-et-apres-le-cancer.-Rapport-d-evaluation. Accessed 29 Feb 2020.

Soubeyran P, Bellera C, Goyard J, Heitz D, Curé H, Rousselot H, et al. Screening for vulnerability in older cancer patients: the ONCODAGE prospective multicenter cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(12):e115060.

Institut National du Cancer. 2011-fiche_de_detection_fragilite_sociale_2-inca.pdf. 2011. https://www.e-cancer.fr/content/download/59312/539202/file/Fiche_de_detection_fragilite_sociale_2.pdf. Accessed 29 Feb 2020.

Fiches conseils médicaments anticancéreux oraux | m.rohlim. 2019.https://m.rohlim.fr/professionnels-de-sante/fiches-conseils/fiches-conseils-medicaments-anticancereux-oraux. Accessed 29 Feb 2020.

Zerillo JA, Goldenberg BA, Kotecha RR, Tewari AK, Jacobson JO, Krzyzanowska MK. Interventions to improve oral chemotherapy safety and quality: a systematic review. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:105–17.

Deppenweiler M, Falkowski S, Saint-Marcoux F, Monchaud C, Picard N, Laroche M-L, et al. Towards therapeutic drug monitoring of everolimus in cancer? Results of an exploratory study of exposure-effect relationship. Pharmacol Res. 2017;121:138–44.

Rougeot J, Nevado E, Maillan G, Marie-Daragon A, Leobon sophie, Tubiana-Mathieu N, et al. 164 PP - Le dispositif de prise en charge des patients traités par thérapie orale au sein d’un service d’oncologie médicale, illustré par la molécule évérolimus. Syndicat National des Pharmaciens Praticiens Hospitaliers et Praticiens Hospitaliers Universitaires; 2016. https://www.snphpu.org/poster.php?HiNum=9535.

Coolbrandt A, Wildiers H, Aertgeerts B, Van der Elst E, Laenen A, Dierckx de Casterlé B, et al. Characteristics and effectiveness of complex nursing interventions aimed at reducing symptom burden in adult patients treated with chemotherapy: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51:495–510.

Poort H, Jacobs JM, Pirl WF, Temel JS, Greer JA. Fatigue in patients on oral targeted or chemotherapy for cancer and associations with anxiety, depression, and quality of life. Palliat Support Care. 2019;18:141–7.

Yahiro Y, Nakai Y, Higashi A. A literature review of studies examining the psychological aspects of cancer patients receiving outpatients chemotherapy. J Jpn Soc Nurs Res. 2012;35:5.

Lai XB, Ching SSY, Wong FKY, Leung CWY, Lee LH, Wong JSY, et al. A nurse-led care program for breast cancer patients in a chemotherapy day center: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer Nurs. 2019;42:20–34.

Handa S, Okuyama H, Yamamoto H, Nakamura S, Kato Y. Effectiveness of a smartphone application as a support tool for patients undergoing breast cancer chemotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Breast Cancer. 2020;20:201.

Lai XB, Ching SSY, Wong FKY, Leung CWY, Lee LH, Wong JSY, et al. The cost-effectiveness of a nurse-led care program for breast cancer patients undergoing outpatient-based chemotherapy—a feasibility trial. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2018;36:16–25.

Occhipinti S, Petit-Jean E, Pinguet F, Beaupin C, Daouphars M, Parent D, et al. Pharmacist involvement in supporting care in patients receiving oral anticancer therapies: a situation report in French cancer centers. Bull Cancer. 2017;104:727–34.

O’Bryant CL, Crandell BC. Community pharmacists’ knowledge of and attitudes toward oral chemotherapy. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2008;48:632–9.

Mekdad SS, AlSayed AD. Towards safety of oral anti-cancer agents, the need to educate our pharmacists. Saudi Pharm J. 2017;25:136–40.

Acknowledgements

We thank Textcheck for assistance with English language editing. The English in this document has been checked by at least two professional editors, both of whom are native English speakers. For a certificate, please see: https://www.textcheck.com/certificate/SdsM8g.

Funding

This project was selected and ethically approved by the National Institute of Cancer (INCa) and the Ministry of Health in 2014 after a call for projects (DGOS/R3/2014/235–24 July 2014) and in 2017 was deemed to be an excellent “Cancer Research Territory” by the French Hospital Federation in collaboration with the National Research Coordination Committee.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NTM, SLD, and GM participated in study conception and design. All authors participated in data acquisition. ED, LM, and SL performed the statistical analyses. NTM, SLD, ED, TD, SL, and KB analysed the data. NTM and SLD supervised the work. NTM, SLD, KB, TD, and ED were the major contributors to manuscript preparation. All authors contributed to the manuscript, critically revised it, and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No author has any conflicts of interest to report.

Ethics approval

All clinical data were collected in accordance with French bioethics laws addressing patient information and consent. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Patients provided written (signed) informed consent to use their medical and administrative data.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Deluche, E., Darbas, T., Bourcier, K. et al. Prospective evaluation of an anti-cancer drugs management programme in a dedicated oral therapy center (DICTO programme). Med Oncol 37, 69 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-020-01393-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-020-01393-7