Abstract

Purpose

Population-based Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) screening and eradication for adults in areas with a high incidence of gastric cancer have been shown to be effective. The current status of H. pylori screening for young people, however, has not been sufficiently evaluated.

Methods

A systematic review of population-based H. pylori screening of young people was performed using four databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, and ICHUSHI) and independently evaluated by two investigators. Studies were evaluated with regard to the country, region, screening method, target age, number of screened people, and rate of positive screening.

Results

From 3231 studies, 39 studies were included (14 English original studies published in peer-review journals, 6 Japanese original studies, and 19 conference reports). These studies originated from 10 countries, with the largest number stemming from Japan (29 studies) followed by Germany (2 studies). Screening was performed using the urea breath test, blood antibodies, stool antigens, and urine antibodies. Five countries used the breath test as the first screening method, five used blood samples, two used stool antigens, and only Japan used urinary tests.

Conclusion

Screening for H. pylori in young people was reviewed based on reports from several countries, and findings suggest that local authorities considering screening for H. pylori in young people need to scrutinize the age and potential methods. Further research is required to determine the effectiveness of mid- to long-term H. pylori screening for young people.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Screening is performed to detect specific diseases among healthy people. There is a wide range of diseases that can be screened for, including infectious diseases [1], chronic diseases [2], and cancer [3, 4]. Screening enables the provision of early treatment to those with positive results and, from a public health perspective, also serves to prevent the spread of infectious disease such as tuberculosis [5], human immunodeficiency virus [6], and syphilis [7], in certain populations. In most cases, the parent organization providing the screening is a public organization, government, or local government. The aim of the screening programs is to prevent the prevalence of disease in a population and the emergence of disease in the future, as well as to enhance the well-being of the population and reduce the social burden of disease. Medical examinations are also conducted where companies provide opportunities for their employees to get tested. The type of screening these entities provide depends on the prevalence a specific disease in the population, cost-effectiveness of screening, and the economic status of the entity. For this reason, the structure and coverage of screening often vary widely across countries and regions. In particular, screening for cancer, which has a higher incidence and is the leading cause of death, is prioritized over communicable diseases, which have a lower mortality in developed countries. In recent years, however, several infectious diseases, including Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), human papillomavirus, hepatitis virus B and C, and others have been shown to pose a risk for the development of cancer and chronic diseases, and this has become a public health challenge in both developing and developed countries [8,9,10].

H. pylori infection causes chronic gastritis and gastroduodenal ulcers and is a major risk factor for gastric cancer. In 1994, the International Cancer Research Agency recognized H. pylori as a class I carcinogenic pathogen to humans. [11,12,13] Eradication of H. pylori is an effective method for reducing the incidence of gastric cancer. Following endoscopic treatment for early-stage gastric cancer, eradication of H. pylori can have a significant inhibitory effect on gastric carcinogenesis [14]. Furthermore, eradication of H. pylori has also recently been shown to reduce the risk of gastric cancer in asymptomatic adults. [15] However, the effect of H. pylori eradication on the risk of gastric cancer has been shown to vary based on the region and race [16]. For example, studies have indicated that it is more effective to eradicate H. pylori in Asian populations with a high incidence of stomach cancer than in Americans [17]. The Asia–Pacific and European guidelines recommend screening for H. pylori in populations at high risk of gastric cancer, regardless of their symptoms. [18, 19] In Japan, multiple H. pylori screening and treatment programs are being conducted in the municipality for adults [20].

While there is a consensus that population-based H. pylori screening and eradication for adults in areas with high gastric cancer incidence is effective in reducing the incidence of gastric cancer, there is controversy regarding H. pylori infection therapy in young people. The benefit of H. pylori eradication in children and adolescents has not yet been clearly established. H. pylori is believed to be infectious in children [21]. It is thought that if H. pylori is eradicated at a young age, reinfection is less likely to occur and eradication in children with dyspepsia has been shown to be effective in improving symptoms [22]. However, whether the test and treat approach in young asymptomatic patients suppresses the long-term development of gastric cancer has yet to be established. Moreover, there is concern that treatment of asymptomatic H. pylori-infected patients may encourage the growth of drug-resistant H. pylori, which has already been a problem [23]. On the other hand, in order to prevent the carcinogenic effects of H. pylori, it is also believed that the earlier the eradication, the better. Pathologically, eradication of H. pylori prior to the progression of chronic gastritis and development of intestinal metaplasia is thought to be effective in controlling carcinogenesis, and therefore, the theory of eradication therapy in young people has merit [24, 25]. For this reason, several municipalities in Japan are offering H. pylori screening for teenagers [26]. Although there has been no clear consensus on the optimal timing of H. pylori eradication, the appropriate eradication strategy for young patients with H. pylori infection needs to be thoroughly discussed.

Although the pros and cons of H. pylori testing and eradication for young people need further and continued analysis, providers of screening programs need to consider its priority. However, despite the clinical need, there have been few reports on the implementation of H. pylori screening in young people. In the present report, we conducted a systematic review to determine whether there is a systematic trend in the implementation of H. pylori screening in Japan and around the world with the purpose of assessing the current status of H. pylori screening for young people.

Methods

In this study we applied the guidelines for conducting a review from Parts 1 and 2 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6 and adhered to the systematic reporting guidelines of the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement. The PRISMA checklist is shown in Supplementary file 1. Our review protocol is shown in Supplementary file 2.

Criteria for Considering Studies for This Review

Types of Studies

In this review, we included available published or unpublished observational studies and conference reports assessing the H. pylori infection. Reviews, survey reports for the purpose of infection rate identification, and case reports that included less than 10 cases were excluded.

Types of Participants

Healthy, asymptomatic persons, including teenagers, screened for H. pylori (with towns or schools being the smallest population units) were included in this review. Patients with symptoms were excluded.

Search Methods for Identification of Studies

We searched MEDLINE (via PubMed, 1966 to 10 December 2018), EMBASE (1966 to 10 December 2018), Cochrane Library (Issue 12 of 12, December 2018), and ICHUSHI (1970 to 10 December 2018), for studies published in either English or Japanese using the search terms “H. pylori infection” and “child.” The search strategy is detailed in Supplementary file 3.

We also performed a search for additional references, by hand, from The Japanese Journal of Helicobacter Research and The Journal of Japanese Gastroenterological Association.

Data collection and Analysis

Selection of Studies

Two authors (HS, YN) independently assessed all potential studies identified using our search strategy for inclusion in this review. Any disagreement was resolved through discussion or, if necessary, by consultation with a third author (YM).

Data extraction and Management

HS extracted the data using a standardized form. The items on the form included study design, countries, cities, participants, methods used for testing (e.g., urine, blood, urea breath), and positive rate.

Assessment of Risk of Bias in Included Studies

Due to this review including observational studies that utilized a variety of methods, we did not evaluate risk of bias.

Data Synthesis

Descriptive summaries of the individual study results are provided for each outcome in table including the characteristics of each review by country and by region within Japan.

Results

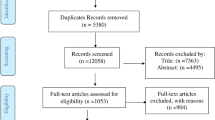

Description of Included Reviews

The flow diagram of the selection process is shown in Fig. 1. A total of 4708 studies were identified from the database search. After removing duplicates, 3231 studies remained. A total of 3133 titles and abstracts were excluded as they did not involve human subjects, did not include young people, or the full text was not available in English. Of the 97 studies remaining, 58 were excluded because they had no illiquidity of testing to specific populations, such as sampling for research purposes and reporting only those that visited the hospital, and three reports were excluded as they were intended for refugees. The excluded studies are detailed in Supplementary file 4. Finally, 39 studies met the inclusion criteria for analysis of which 14 were English original studies published by peer-review journals [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39], 7 Japanese original studies, [40,41,42,43,44,45,46], and 18 conference reports. [47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64]

Study Characteristics

The 39 studies were reported from 10 countries, with the largest number stemming from Japan (29 studies) followed by Germany (2 studies). Screening was performed using the urea breath test, blood antibodies, stool antigens, and urine antibodies; five countries used the urea breath test as their first method of screening, five used blood samples, two used stool antigens, and only Japan used urinary tests. The age range of the subjects varied from country to country and from report to report (Table 1). The size of the population tested for H. pylori also varied between studies, ranging from school-based surveys to town or city-wide populations. Furthermore, the reported positive rates significantly differed between studies with the reported rates ranging from 2.6 to 72.4%. In Japan, four original articles in English peer-reviewed journals, seven original articles in Japanese journals, and 18 conference abstracts were published. Eleven prefectures and 17 cities or towns conducted screening for H. pylori in young people. Characteristics of the prefecture screenings are shown in Table 2. The most common test used for primary screening was the urine antibody test conducted in nine prefectures, followed by blood antibodies in three prefectures, and the fecal antigen test and urea breath test in two prefectures. The reported positive rate of H. pylori was low in Japan (2.6%-9.5%) compared with that in other countries. The main stakeholders providing screening were local governments in prefectures or municipalities, local medical associations, and university hospitals; in some areas, these branches worked together to deliver H. pylori screening programs.

Discussion

Summary

In this study, we clarified, for the first time, the present status of H. pylori screening for young people worldwide. We screened 3231 reports, of which 97 reports were reviewed and 39 were included in our analysis. We then summarized the results, by country, in terms of screening methods, number of screenings, and positive rates. This review was independently screened by two reviewers, aiming to reduce selection bias. However, it should be noted that we only included English and Japanese literature; furthermore, we included grey literature and there were limitations with regards to assessing the quality of the literature.

Demographic of the H. pylori Screening for Young People

The prevalence of gastric cancer varies greatly by country and region, and differences in regional H. pylori infection rates and H. pylori pathogenicity have an impact on said prevalence [65,66,67]. For this reason, it is thought that strategies for H. pylori treatment for the prevention of gastric cancer will differ between populations. Currently, screening for H. pylori is recommended in areas with high H. pylori infection rates and a high incidence of gastric cancer. [18, 19] Our study, however, included countries from areas with both high and low incidences of gastric cancer and noted substantial differences in the age-standardized incidence rate (ASR) between countries. The ASR of gastric cancer per 100,000 of population in the countries included in this study are reported to be 39.6 in South Korea, 27.5 in Japan, 20.7 in China, 8.3 in Poland, 7.9 in Brazil, 7.2 in Italy, 6.7 in Germany, 4.2 in Finland, 3.9 in Uganda, and 2.8 in Egypt. Eradication of H. pylori is a preventive measure against gastric cancer, as well as a preventive measure against peptic ulcers, MALT lymphoma, iron deficiency anemia, and immune thrombocytopenic purpura, issues that can arise in children and young people [68,69,70]. It is possible that efforts to screen young people for H. pylori in areas with a low incidence of gastric cancer may not be aimed solely at the preventive effect of gastric cancer.

The age at which the screening approach should be initiated is controversial. This review indicated that a proportion of the studies included, especially those from Japan, were found to be screening young people at junior high school. This is because junior high school education is compulsory in Japan, an environment that allows for the targeting of all young people in the region. Even if screening is done at an early age, such as elementary school, therapeutic intervention then raises concerns with regard to antibiotic capacity and side effects. As such, it would be potentially be more effective to introduce screening as part of a junior high or high school health check-up. It is theorized that these “test and treatment” efforts will contribute to reducing the incidence of gastric cancer in the population and will also contribute to reducing the prevalence of H. pylori in the future. However, long-term trends require ongoing monitoring.

Screening Method

The screening method reported in the study included a urine test, blood test, stool test, and urea breath test. Of these, urine tests were used only in Japan. Although this study did not include a detailed inspection, the sensitivity and specificity of the test, the cost of the test, and the simplicity of the test were the main factors in the selection of the testing method for screening. The sensitivity and specificity of the fecal antigen test and urea breath test are higher than those of blood and urine antibodies test. The cost is generally higher for the urea breath test, which requires reagents. Urea breath tests and urine tests are not invasive, but blood antibodies require a blood draw. Some believe that fecal testing is unsuitable for young people because of the photophobia associated with it. When introducing screening, a balance between sensitivity and specificity, cost, and simplicity should be considered when deciding on the testing method.

Current Screening Implementation

Many of the communities in this study that screened for H. pylori at a young age were using a schooling framework [26, 27, 30, 32, 37,38,39,40,41, 43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61, 63]. Two studies used a pre-enrolment health screening mechanism [34, 35], while others implemented the initiative as part of a health screening during school. Schooling, in which everyone participates, is used to cover all of a generation’s population. In addition, in some areas, H. pylori screening for young people was conducted as a part of a screening program for the entire population. Municipalities that are considering implementing H. pylori screening should determine what framework they will use and its impact on the population to be targeted, ease of participation in screening, and screening coverage.

The impact of testing and treatment of young asymptomatic patients for H. pylori on the prevention of future gastric cancer is not well understood. While there have been efforts to screen young people for H. pylori to reduce the risk of future gastric cancer and prevent infection, some reports have suggested that H. pylori testing and treatment should not be performed, at least in asymptomatic children, because of concerns regarding the overuse of antibiotics and subsequent side effects. [71]

None of the literature collected for the current study assessed the mid- to long-term impact of screening for H. pylori in young people. How screening and treatment of healthy children and adolescents for H. pylori will contribute to reducing the risk of future cancer, including long-term adverse events, remains to be studied.

Compared with testing of adults, testing of adolescents and children may require additional considerations. None of the papers in this study used invasive methods such as endoscopy, which is different from testing for adults. There were no reports of major adverse occurrences in any of the studies included in this review. However, special attention should be paid to the occurrence of adverse events as a result of screening, especially in younger generations. The main reason for endoscopy in adults prior to H. pylori eradication is to screen for any potential gastric cancer that may have already developed. In contrast, in adolescents, the likelihood of this is low, and thus, the benefits of endoscopy are greatly limited. At the very least, a credible and safe method should be used for H. pylori screening in younger populations. For this reason, it is reasonable to use a combination of urine and blood tests, urea breath tests, and stool tests to diagnose and eradicate H. pylori.

Finally, none of the studies included in this review compared and discussed the cost of the different types of tests. When administrations initiate screening for disease, its cost-effectiveness needs to be considered. The price of the test itself, the sensitivity and specificity of the test, the time it takes to perform the test, and adherence to the test should be considered when deciding on the screening method. A strategy that combines several tests to avoid the possibility of false-negative results is ideal. [72]

Limitations

The current study has several limitations. First, the current review was based on studies in which the H. pylori test was performed on a population with a thoroughness. This may result in fewer reports than those that have actually been screened. In addition, the results of the present study are not representative of all regions, as report bias may occur. This study includes Japanese literature, and therefore the study may be more relevant in Japan. Stomach cancer is more common in Japan, and more papers have been published on the pros and cons of screening adolescents for H. pylori, so we judged that this would provide important insights. A more comprehensive survey is to achieve a thorough overview of H. pylori screening in young people worldwide.

Conclusions

Screening for H. pylori in young people was reported from countries around the world. Various methods were used, including urinary antibodies, blood antibodies, stool antigens, and the urea breath test, and less invasive methods should be considered for H. pylori screening in young people. Studies observing the effects of H. pylori screening on young people in the medium- to long-term were scarce, and as such, further research is required to ascertain these effects. Future study should be conducted in collaboration with the local government, which is the main body of the health care management for young people.

Availability of Data and Material

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

Change history

21 April 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12029-021-00636-8

References

Moyer VA: Screening for hepatitis C virus infection in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2013;159(5):349–7.

Jankowski P, Banach M, Małyszko J, Mastej M, Tykarski A, Narkiewicz K, Hoffman P, Nowicki MP, Tomasik T, Windak A, et al. May measurement month 2018: an analysis of blood pressure screening campaign results from Poland. European heart journal supplements : journal of the European Society of Cardiology. 2020;22(Suppl H):H108-h111.

Siu AL, Force USPST: Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med 2016;164(4):279–6.

White A, Thompson TD, White MC, Sabatino SA, de Moor J, Doria-Rose PV, Geiger AM, Richardson LC. Cancer screening test use—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(8):201–6.

Yoon C, Dowdy DW, Esmail H, MacPherson P, Schumacher SG. Screening for tuberculosis: time to move beyond symptoms. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(3):202–4.

Kahn JG, Bendavid E, Dietz PM, Hutchinson A, Horvath H, McCabe D, Wolitski RJ. Potential contributions of clinical and community testing in identifying persons with undiagnosed HIV infection in the United States. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care. 2020;19:2325958220950902.

An Q, Bernstein KT, Balaji AB, Wejnert C. Sexually transmitted infection screening and diagnosis among adolescent men who have sex with men, three US cities, 2015. Int J STD AIDS. 2020;31(1):53–61.

Hooi JKY, Lai WY, Ng WK, Suen MMY, Underwood FE, Tanyingoh D, Malfertheiner P, Graham DY, Wong VWS, Wu JCY, et al. Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(2):420–9.

Liu Z, Shi O, Zhang T, Jin L, Chen X: Disease burden of viral hepatitis A, B, C and E: a systematic analysis. J Viral Hepat. 2020;27(12):1284–1296.

Jee B, Yadav R, Pankaj S, Shahi SK: Immunology of HPV-mediated cervical cancer: current understanding. Int Rev Immunol. 2020:1–20.

Huang JQ, Sridhar S, Chen Y, Hunt RH. Meta-analysis of the relationship between Helicobacter pylori seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 1998;114(6):1169–79.

Eslick GD, Lim LL, Byles JE, Xia HH, Talley NJ. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with gastric carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(9):2373–9.

Nomura A, Stemmermann GN, Chyou PH, Kato I, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric carcinoma among Japanese Americans in Hawaii. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(16):1132–6.

Choi IJ, Kook MC, Kim YI, Cho SJ, Lee JY, Kim CG, Park B, Nam BH. Helicobacter pylori therapy for the prevention of metachronous gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(12):1085–95.

Lee YC, Chiang TH, Chou CK, Tu YK, Liao WC, Wu MS, Graham DY. Association between Helicobacter pylori eradication and gastric cancer incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(5):1113-1124.e1115.

Ford AC, Yuan Y, Forman D, Hunt R, Moayyedi P. Helicobacter pylori eradication for the prevention of gastric neoplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;7(7):Cd005583.

Kim GH, Liang PS, Bang SJ, Hwang JH. Screening and surveillance for gastric cancer in the United States: is it needed? Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84(1):18–28.

Talley NJ, Fock KM, Moayyedi P. Gastric Cancer Consensus conference recommends Helicobacter pylori screening and treatment in asymptomatic persons from high-risk populations to prevent gastric cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(3):510–4.

Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, Atherton J, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gensini GF, Gisbert JP, Graham DY, Rokkas T, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection—the Maastricht IV/ Florence consensus report. Gut. 2012;61(5):646–64.

Yamaguchi Y, Nagata Y, Hiratsuka R, Kawase Y, Tominaga T, Takeuchi S, Sakagami S, Ishida S. Gastric cancer screening by combined assay for serum anti-Helicobacter pylori IgG antibody and serum pepsinogen levels—the ABC method. Digestion. 2016;93(1):13–8.

Goh KL, Chan WK, Shiota S, Yamaoka Y. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection and public health implications. Helicobacter. 2011;16(Suppl 1):1–9.

Ünlüsoy Aksu A, Yılmaz G, Eğritaş Gürkan Ö, Sarı S, Dalgıç B. The effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on functional dyspepsia in Turkish children. Helicobacter. 2018;23(4):e12497.

Lahaie RG, Gaudreau C: Helicobacter pylori antibiotic resistance: trends over time. Can J Gastroenterol = Journal Canadien de Gastroenterologie. 2000;14(10):895–9.

Eusebi LH, Telese A, Marasco G, Bazzoli F, Zagari RM. Gastric cancer prevention strategies: a global perspective. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35(9):1495–1502.

Suzuki H, Mori H. Helicobacter pylori: Helicobacter pylori gastritis—a novel distinct disease entity. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12(10):556–7.

Akamatsu T, Ichikawa S, Okudaira S, Yokosawa S, Iwaya Y, Suga T, Ota H, Tanaka E. Introduction of an examination and treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection in high school health screening. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46(12):1353–60.

Szaflarska-Popławska A, Soroczyńska-Wrzyszcz A. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among junior high school students in Grudziadz, Poland. Helicobacter. 2019;24(1):e12552.

Yim JY, Kim N, Choi SH, Kim YS, Cho KR, Kim SS, Seo GS, Kim HU, Baik GH, Sin CS, et al. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori in South Korea. Helicobacter. 2007;12(4):333–40.

Hestvik E, Tylleskar T, Kaddu-Mulindwa DH, Ndeezi G, Grahnquist L, Olafsdottir E, Tumwine JK. Helicobacter pylori in apparently healthy children aged 0–12 years in urban Kampala, Uganda: a community-based cross sectional survey. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:62.

Mohammad MA, Hussein L, Coward A, Jackson SJ. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among Egyptian children: Impact of social background and effect on growth. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11(3):230–6.

Dattoli VC, Veiga RV, da Cunha SS, Pontes-de-Carvalho LC, Barreto ML, Alcantara-Neves NM. Seroprevalence and potential risk factors for Helicobacter pylori infection in Brazilian children. Helicobacter. 2010;15(4):273–8.

Tam YH, Yeung CK, Lee KH, Sihoe JDY, Chan KW, Cheung ST, Mou JWC. A population-based study of Helicobacter pylori infection in Chinese children resident in Hong Kong: prevalence and potential risk factors. Helicobacter. 2008;13(3):219–24.

Salomaa-Rasanen A, Kosunen TU, Aromaa AR, Knekt P, Sarna S, Rautelin H. A “screen-and-treat” approach for Helicobacter pylori infection: a population-based study in Vammala. Finland Helicobacter. 2010;15(1):28–37.

Rothenbacher D, Bode G, Berg G, Knayer U, Gonser T, Adler G, Brenner H. Helicobacter pylori among preschool children and their parents: evidence of parent-child transmission. J Infect Dis. 1999;179(2):398–402.

Bode G, Rothenbacher D, Brenner H, Adler G. Helicobacter pylori and abdominal symptoms: a population-based study among preschool children in Southern Germany. Pediatrics. 1998;101(4):634–7.

Dominici P, Bellentani S, Di BAR, Saccoccio G, Le RA, Masutti F, Viola L, Balli F, Tiribelli C, Grilli R, et al. Familial clustering of Helicobacter pylori infection: population based study. Br Med J. 1999;319(7209):537–41.

Honma H, Nakayama Y, Kato S, Hidaka N, Kusakari M, Sado T, Suda A, Lin Y: Clinical features of Helicobacter pylori antibody-positive junior high school students in Nagano Prefecture, Japan. Helicobacter. 2018:e12559.

Akamatsu T, Okamura T, Iwaya Y, Suga T. Screening to identify and eradicate Helicobacter pylori infection in teenagers in Japan. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2015;44(3):667–76.

Kusano C, Gotoda T, Suzuki S, Ikehara H. The administrative project of Helicobacter pylori infection screening among junior high school students in an area of Japan with a high incidence of gastric cancer. Gut. 2018;67:A43–4.

Okuda M, Tachikawa T, Osaki Y, Maekawa K. Focusing on examination and diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori in junior high school students in Sasayama City (in Japanese). The Journal of the Japan Pediatric Society. 2014;118(2):326.

Okamura T, Suga T, Yokosawa S, Niikura N, Matsumoto T, Okudaira S, Akamatsu T, Tanaka E. Introduction of H. pylori screening into routine school medical examinations (in Japanese). Jpn J Helicobacter Res. 2015;16(2):10–15.

Shinichi F, Mutsuko K, Nariaki T, Michiko T, Shinichi Y. A study on the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in children in urban and rural areas (in Japanese). The Mutual Aid Examiner Newsletter. 2015;37:25–9.

Sasaki Y, Yuichi A, Yukari Y, Hiroki K. Helicobacter pylori screening in junior high school students in Abashiri City] (in Japanese). J Clin Pediatr, Sapporo. 2017;65(1–6):21–4.

Kousen K, Miyamura T, Ogasawara M, Mabe K, Kato M. Helicobacter pylori screening for junior high school students (first report) as a medical association project with the aim of eradicating gastric cancer in the area (in Japanese). J Med Assoc South Hokkaido. 2018;Supplement 1.

Handa O. Medical trends Kyoto First year high school pylori project (in Japanese). Schneller. 2018;106:8–12.

Ichikawa S, Akamatsu T, Okudaira S. Selection and expansion of H. pylori eradication therapy. Introduction of Helicobacter pylori infection screening tests in school screening (in Japanese). Gastroenterology. 2009;48(1):1–5.

Akifuji Y, Amano M, Okamoto T, Takami H, Miyakawa T, Kawamoto T, Tsukuda S, Igori J, Ootani M: Helicobacter pylori screening for primary prevention of gastric cancer in junior high school students in Hokuei Town, Tottori Prefecture, Japan (first report) (in Japanese). In: Tottori Medical Association Spring Medical Conference. 2016.

Kaji E, Yoda A, Aomatsu T, Okudaira T, Akamatsu M, Tamai H: How Helicobacter pylori screening and eradication for the prevention of gastric cancer in junior high school students: Takatsuki-shi pediatric H. pylori study (2014) (in Japanese). J Jpn Pediatr Soc. 2016;120(2):208.

Ota Y, Otsuka T, Tomidokoro T. Examination of H. pylori in junior high school students in Nagaoka City (in Japanese). J Jpn Pediatr Soc. 2018, 122(8):1379–1380

Okuda M. Diagnosis and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in childhood—toward screening and eradication of Helicobacter pylori in junior and senior high school students for prevention of gastric cancer (in Japanese). Bulletin of the Osaka Pediatricians’ Association. 2015;172:26–7.

Okuda M, Kikuchi S, Mabe K, Kato M. [How should junior high school students be screened for Helicobacter pylori and eradicated to prevent gastric cancer? Screening and eradication of Helicobacter pylori in junior high school students for the prevention of gastric cancer Including the initiatives of Sasayama City and a nationwide survey](in Japanese). The Journal of the Japan Pediatric Society. 2016;120(2):207.

Tachikawa T, Fujino E, Maekawa K, Okuda M, Fukuda Y, Fujino T, Ueda J, Kikuchi S. Screening for Helicobacter pylori in junior high school students in Sasayama City (in Japanese). The Journal of the Japan Pediatric Society. 2014;118(6):965.

Okamura t, Suga T, Niikura N. Introduction of screening for H. pylori infection to school screening and examination of pepsinogen levels in high school students in relation to strategies to reduce gastric cancer mortality (in Japanese). J Jpn Soc Gastroenterol. 2014;111:A720.

Okuda M, Kikuchi S, Mabe K, Kato M, Fukuda Y. Screening for Helicobacter pylori and treatment for gastric cancer in junior high school students (in Japanese). J Jpn Soc Gastroenterol. 2014;111:A255.

Mabe K, Miyamoto S, Mizushima T, Ono M, Omori S, Ono S, Shimizu Y, Kato M, Asaka M: The strategy of test and treat for H. Pylori infection to junior and senior high school students in Hokkaido, Japan. Helicobacter. 2014;19:162.

Fujiwara S, Konno M, Hattori T, Doyama A, Tosaka N, Takahashi M. How Helicobacter pylori screening and eradication for the prevention of gastric cancer should be performed in junior high school students: a study of mass screening for H. pylori and eradication in Memuro-cho (in Japanese). J Jpn Pediatr Soc. 2016;120(2):207.

Kakiuchi T, Nakayama A, Matsuo M. Helicobacter pylori “Program to promote measures against gastric cancer for the future” screening in all third-year junior high schools in Saga Prefecture (in Japanese). The general meeting of the Japanese Society of Gastroenterology. 2017;121(2):339.

Yamashita N, Inoue K, Ishii M, Imamura Y, Mabe N, Kamata T, Kusunoki H, Shioya A, Hatake J, Kondo H et al. Serum pepsinogen levels and ABC classification of H. pylori-positive junior high school students (in Japanese). Japan Gastroenterological Cancer Screening Congress. 2014;52(5):215.

Ichikawa S, Akamatsu T, Ito T, Sudo M, Yoneda S, Sudo T, Takeda R, Takenaka K, Nagaya M, Kitahara K et al. Introduction of Helicobacter pylori infection screening test in school screening-focusing on the results of secondary examinations (in Japanese). Gastroenterol Endosc. 2009;51:Page815.

Akamatsu T, Kaneko Y, Suzawa K. Expansion of indications for H. pylori eradication therapy (in Japanese). J Jpn Soc Gastroenterol 2008;100:A46.

Ono K, Handa K. Establishment of a screening system for junior high school students by Helicobacter pylori antibody testing (in Japanese). J Jpn Soc Gastroenterol. 2016;113:A699.

Kitagawa K, Taguchi J: Helicobacter pylori screening in junior high school students (in Japanese). In: National Association for Regional Health Care. 2017.

Kusano C, Gotoda T, Suzuki S, Kono S, Iwatsuka K. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in children in an area of Japan with a high incidence of gastric cancer: a population-based cross-sectional study. Journal of Gastroenterology. 2016;150(4):S438.

Ichikawa S, Akamatsu T, Sudo T, Takeda R, Takenaka K, Nagaya M, Tanaka E. Introduction of screening test for Helicobacter pylori infection into school examinations Drug Resistance and Eradication Outcomes in Secondary Screening (in Japanese). J Jpn Soc Gastroenterol. 2009;106:A769.

Perez-Perez GI, Rothenbacher D, Brenner H. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2004;9(Suppl 1):1–6.

Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Orentreich N, Vogelman H. Risk for gastric cancer in people with CagA positive or CagA negative Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut. 1997;40(3):297–301.

Kuipers EJ, Pérez-Pérez GI, Meuwissen SG, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori and atrophic gastritis: importance of the cagA status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87(23):1777–80.

Hudak L, Jaraisy A, Haj S, Muhsen K: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis on the association between Helicobacter pylori infection and iron deficiency anemia. Helicobacter. 2017;22(1).

Goddard AF, James MW, McIntyre AS, Scott BB. Guidelines for the management of iron deficiency anaemia. Gut. 2011;60(10):1309–16.

Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, Gisbert JP, Kuipers EJ, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gasbarrini A, Atherton J, Graham DY, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection—the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2017;66(1):6–30.

Jones NL, Koletzko S, Goodman K, Bontems P, Cadranel S, Casswall T, Czinn S, Gold BD, Guarner J, Elitsur Y, et al. Joint ESPGHAN/NASPGHAN Guidelines for the Management of Helicobacter pylori in Children and Adolescents (Update 2016). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;64(6):991–1003.

Saito H, Nishikawa Y, Mizuno Y. Patient outcomes and environment may affect adherence to Helicobacter pylori testing. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020; S1542-3565(20)30936-8.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful to Ms. Erika Yamashita for her help in organizing and extracting the literature and Mr. Anju Murayama for organizing the literature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Review preparation and data management: HS; Study concept and design: HS, YN, YuM; Data acquisition: HS, YN, YuM; Study selection: HS, YN, YuM; Drafting the manuscript: HS, YN, YuM; Supervision: MT, YaM.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. supported the acquisition of the literature but was not involved in the conduct of the study.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Saito, H., Nishikawa, Y., Masuzawa, Y. et al. Helicobacter pylori Infection Mass Screening for Children and Adolescents: a Systematic Review of Observational Studies. J Gastrointest Canc 52, 489–497 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12029-021-00630-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12029-021-00630-0