Abstract

Background/objective

Monitoring of brain tissue oxygen tension (PbtO2) provides insight into brain pathophysiology after intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). Integration of probe location is recommended to optimize data interpretation. So far, little is known about the importance of PbtO2 catheter location in ICH patients.

Methods

We prospectively included 40 ICH patients after hematoma evacuation (HE) who required PbtO2-monitoring. PbtO2-probe location was evaluated in all head computed tomography (CT) scans within the first 6 days after HE and defined as location in the healthy brain tissue or perilesional when the catheter tip was located within 1 cm of a focal lesion (hypodense or hyperdense). Generalized estimating equations were used to investigate levels of PbtO2 in relation to different probe locations.

Results

Patients were 60 [51–66] years old and had a median ICH-volume of 47 [29–60] mL. Neuromonitoring probes remained for a median of 6 [2–11] days. PbtO2-probes were located in healthy brain tissue in 18/40 (45%) patients and in perilesional brain tissue in 22/40 (55%) patients. In the acute phase after HE (0–72 h), PbtO2 levels were significantly lower (21 ± 12 mmHg vs. 29 ± 10 mmHg, p = 0.010) and brain tissue hypoxia (BTH) was more common in the perilesional area as compared to healthy brain tissue (46% vs. 19%, adjOR 4.0, 95% CI 1.54–10.58, p = 0.005). Episodes of BTH significantly decreased over time in patients with probes in perilesional location (p = 0.001) but remained stable in normal appearing area (p = 0.485). A significant association between BTH and poor functional outcome was only found when probes were located in the perilesional brain tissue (adjOR 6.6, 95% CI 1.3–33.8, p = 0.023).

Conclusions

In the acute phase, BTH was more common in the perilesional area compared to healthy brain tissue. The improvement of BTH in the perilesional area over time may be the result of targeted treatment interventions and tissue regeneration. Due to the localized measurement of invasive neuromonitoring devices, integration of probe location in the clinical management of ICH patients and in research protocols seems mandatory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite improvements in the neurocritical care management of patients with hemorrhagic stroke over the past decades [1], intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is still a devastating disease associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality [2]. Multimodal neuromonitoring, including brain tissue oxygen tension (PbtO2) monitoring, provides insight into pathophysiologic changes of secondary brain injury, which in turn may open the opportunity to initiate interventions aiming to prevent additional brain damage [3]. As the assessment of PbtO2 is restricted to a small volume of brain tissue surrounding the tip of the probe, integration of probe location seems essential to optimize data interpretation and is therefore also recommended by guidelines and consensus statements [4, 5]. Primary placement of neuromonitoring catheters depends on the underlying disease entity, lesion location, and technical feasibility [4]. In patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) PbtO2 probes should be placed in the lesioned hemisphere (hemisphere with higher lesion load, respectively) in order to detect brain tissue hypoxia in areas at highest risk for secondary injury [3, 6]. Absolute PbtO2 values may differ depending on the type of probe used [7] and probe location [5, 6].

Despite the assumed importance of neuromonitoring probe location in patients with ICH, no data describe the impact of probe location on absolute PbtO2 levels, their temporal dynamics and implications regarding outcome prediction. We hypothesized that multimodal neuromonitoring probe location largely influences PbtO2 levels and has an impact in the prediction of outcome after ICH. Therefore, we aimed to examine the influence of catheter location on PbtO2 levels and whether the prognostic association of brain tissue hypoxia (PbtO2 < 20 mmHg) with functional outcome depends on probe location.

Methods

Patient Population and Study Setting

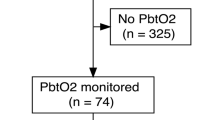

Prospectively recorded observational data of 51 consecutive spontaneous ICH patients fulfilling the inclusion/exclusion criteria for multimodal neuromonitoring admitted to the neurological intensive care unit (NICU) at a tertiary care center between 2011–2018 were studied. Neuromonitoring was initiated after hematoma evacuation (HE) in all patients and comprised assessment of brain tissue oxygen tension (PbtO2), intracranial pressure (ICP), and cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP). Patients were excluded if PbtO2 probes were dysfunctional (n = 7) or when recording time was less than 12 h (n = 4), leaving 40 patients eligible for the final analysis (Fig. 1). General inclusion criteria encompassed (1) admission with non-traumatic ICH diagnosed on cerebral imaging, (2) age ≥ 18 years, (3) hematoma evacuation, including the placement of invasive multimodal neuromonitoring as part of routine clinical care. The study was approved by the local ethics committee of the Medical University of Innsbruck (AN4088292/4.3, AM4091-292/4.6). Informed consent was obtained from all patients according to local regulations in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. The reporting of data conforms to the STROBE guidelines.

Patient Management and Data Collection

Clinical management of ICH patients conformed to current international guidelines set forth by the American Heart Association and European Stroke Association [8, 9]. The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE-II) Score [10] and the ICH Score [11] were used to assess the clinical and radiographic initial disease severity. Patients’ baseline characteristics, hospital complications, treatment interventions and outcomes were prospectively recorded in our institutional ICH database and confirmed in weekly meetings of the study team and treating neurointensivists. Continuous parameters (ICP, CPP, blood pressure (BP), PbtO2) were saved in our patient data management system (Centricity™ Critical Care 8.1 SP7; GE Healthcare Information Technologies, Dornstadt, Germany) and averaged (mean) over one hour. Up to the discretion of the treating neurointensivist, head computed tomography (CT) scans were performed, with the first CT scan obtained in all patients at admission, within the first 24 h and if clinically indicated. Hematoma volumes were calculated using the (ABC)/2 method on the admission CT and are given in milliliters (mL) by a blinded member of the study team [12].

Functional outcome was assessed by a study nurse blinded to the clinical course of patients using the modified Rankin Scale Score (mRS) 3 months after NICU discharge. In view of the high proportion of poor outcomes in patients with large size ICH, a mRS ≤ 4 was compared to a mRS between 5 and 6.

Neuromonitoring and Probe Location

In this study, the decision to evacuate the hematoma was carefully evaluated in all patients by an interdisciplinary team including neurointensivists and neurosurgeons and performed by either surgical craniotomy (N = 32/40, 80%) or hemicraniectomy (N = 8/40, 20%). ICP was measured using a parenchymal ICP-probe (NEUROVENT-P-TEMP; Raumedic®, Helmbrechts, Germany) and PbtO2 by using a Licox® CC1.SB probe (Integra LifeSciences, Ratingen, Germany). None of the authors reposted any conflict of interest regarding the oxygen monitoring systems used. Whenever possible, multimodal monitoring probes were placed in the perihematomal brain tissue in order to monitor the tissue at highest risk for secondary brain injury. Probes were placed after HE without stereotactic support. Following the user manual, there is no requirement for a specific calibration as each PbtO2 probe includes a designated Smart Card. Additionally, FiO2 (FiO2 100% for 5 min) challenges were performed daily to check the functionality of the probe. All patients were mechanically ventilated and received appropriate sedative medication as needed.

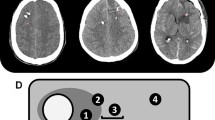

The first CT scan after surgery was obtained within 24 h after probe insertion to evaluate probe location. Probe location was assessed by an independent neuroradiologist and AL on all available head CT scans within the first 6 days. If the tip of the PbtO2-probe was located within a 1-cm distance of a focal hyperdense lesion (parenchymal hemorrhage) and/or focal hypodense lesion (perihematomal edema, focal brain edema, ischemia), the location was defined as perilesional, which mostly reflected the perihematomal area. If there was no focal lesion within 1 cm of the tip, probe location was graded as normal-appearing brain tissue. (Fig. 2) Whenever there was direct contact with the hemorrhage (intralesional location), the data was excluded from the analysis. Brain tissue hypoxia (BTH) was defined as mean PbtO2 < 20 mmHg over one hour as considered in the Consensus Conference on Multimodality Monitoring in Neurocritical care and the current Seattle Consensus Statement and was treated in a stepwise multifactorial approach using an institutional protocol including a CPP target > 70 mmHg [4, 13, 14].

Data Management and Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables (PbtO2, CPP, ICP, BP) were assessed for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and reported as median and interquartile range [IQR] or mean and standard error of the mean (SEM), as appropriate. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 24 (IBM SPSS Statistics, version 24.0. Armonk, NY, USA). The acute phase (≤ 72 h) was compared with the subacute phase (73–168 h), for the assessment of temporal dynamics. To evaluate the impact of probe location on brain oxygenation, generalized estimating equations (GEEs) with the correlation matrix best fitting the data were used for time-series data analysis in order to account for repeated measurements within one patient. All multivariable models were corrected for predefined variables (age, GCS at admission and ICH volume at admission) based on their potential confounding influence on brain oxygenation and indicated appropriately [5, 15]. Adjusted odds ratios (adjOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. In the same way, the associations with functional outcome were analyzed by using the dichotomized outcome factor as independent variable. Statistical significance was judged to a p value < 0.05. Graphical presentation was done using GraphPad Prism 7.

Results

Patient characteristics, hospital complications and outcomes of 40 ICH patients are presented in Table 1. There was no difference in between patient groups (patients with probes in healthy brain tissue compared to those with probes in perilesional brain tissue). Patients were 60 [51–66] years old and had a median ICH volume of 47 [29–60] mL. All patients underwent hematoma evacuation, with a median of 9 [4–32] hours from hospital admission. Neuromonitoring probes were placed during surgery and remained for a median of 6 [2–11] days. In total, 89 head CT scans (2 [2–3] CT scans per patient) of the first 6 days after admission were analyzed. Median time to head CT scan after HE was 10 [5–14] hours. There were no neurosurgical complications recorded within the study time, including instant rebleeding or infarction related to the surgical procedure.

PbtO2-probes were located in healthy brain tissue in 18/40 (45%) patients and in perilesional brain tissue in 22/40 (55%) patients. Importantly, cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) did not differ in patients with different probe locations both, during the early (p = 0.300) and delayed phase (p = 0.613) after HE. Episodes (> 1 h) of ICP ≥ 22 mmHg and mean number of administrations of osmotherapy were higher in patients with perihematomal probe location, although the results did not reach significant levels (p = 0.060 and p = 0.114, respectively).

In healthy brain tissue, mean PbtO2 levels were 29 ± 10 mmHg and in perilesional location 25 ± 12 mmHg (p = 0.144). Episodes of brain tissue hypoxia (BTH, PbtO2 < 20 mmHg) occurred in both groups (overall: 24% of monitoring time) and were slightly more common when PbtO2 was measured in the perilesional area (31% versus 18%, p = 0.074). (Table 2).

Trends in Brain Tissue Oxygen Tension Over Time in Relation to Probe Location

In two patients, we found a shift of catheter tip location from healthy brain tissue to perilesional tissue (n = 1) or from perilesional location to intralesional placement (n = 1); in all other patients probe location remained in the same position during neuromonitoring time. In the early phase after surgery (≤ 72 h), PbtO2 levels were significantly lower in comparison to the subacute phase (21 ± 12 mmHg vs. 29 ± 10 mmHg, p = 0.010; Fig. 3, Panel A). In the early phase, BTH was more common in the perilesional area compared to healthy brain tissue (46% vs. 19%, adjOR 4.0, 95% CI 1.54–10.58; p = 0.005, Fig. 3; Panel B) even after adjusting for admission GCS Score, age and ICH volume. Episodes with BTH significantly decreased over time in patients with probes in perilesional location (from 42% on day 0 to 14% on day 6, p < 0.001). Episodes with BTH remained stable when probes were located in normal appearing area (p = 0.485). There was no impact of probe location on BTH during the subacute phase (BTH: 16% vs. 17%, adjOR 1.1, 95% CI 0.29–4.1, p = 0.884).

PbtO2-Probe Location and Outcome

Patients severely disabled or dead (mRS ≥ 5) 3 months after ICH showed a trend toward lower overall PbtO2 values (25.5 [19.7–32.8] mmHg vs. 28.8 [20.6–36.1] mmHg, p = 0.201) and a higher incidence of BTH than patients with better outcome (26% vs. 23%, p = 0.336). Multivariable analysis revealed a significant association between BTH and major disability or death (adjOR 6.6, 95% CI 1.3–33.8, p = 0.023) when probes were located in the perilesional brain tissue. Moreover, patients severely disabled or dead showed a trend toward lower mean PbtO2 values, when probes were placed in perilesional location (23 [23–29] mmHg vs. 27 [17–36] mmHg), compared to patients with better outcome (adjOR 0.92, 95% CI 0.83–1.01, p = 0.086). Neither BTH nor PbtO2 were associated with functional outcome when the probe was placed in healthy brain tissue (p = 0.807 and p = 0.465, respectively). All models were adjusted for admission GCS score, ICH volume and age. (Table 3).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study analyzing the impact of PbtO2-probe location on longitudinal PbtO2 levels in patients with spontaneous ICH. The main findings of this study are that (1) episodes of brain tissue hypoxia are more frequent in the perilesional location and (2) that lower PbtO2 levels were only associated with 3-month functional outcome when the probe was located close to a lesion.

Invasive multimodal neuromonitoring can provide insight into metabolic, electrographic and oxygenation changes in distinct areas of the brain. [5, 16] It is crucial to integrate catheter location for data interpretation although an individualized treatment concept has not been developed so far [13, 16]. The impact of catheter location has been described in patients with TBI and SAH [17,18,19,20], but has not been systematically analyzed in ICH patients so far.

PbtO2 values reflect the balance between oxygen delivery, consumption, tissue diffusion and extraction [21] and can be influenced by various factors such as cerebral autoregulation status [22, 23], neurovascular coupling [24], CO2 levels [25], probe location [5, 6] as well as factors that contribute to an increased consumption of local oxygen such as fever [26], spreading depolarizations [27] and epileptic seizures [28].

It is recommended to insert the tip of the PbtO2 catheter in the most affected hemisphere targeting “perilesional” brain tissue in TBI patients [5, 6]. In patients with diffuse brain injury, neuromonitoring probes should be inserted in the non-dominant frontal lobe. In patient with SAH, catheters should be placed in the brain tissue of watershed of the aneurysm bearing vessel [29]. For ICH patients, there is no recommendation regarding the optimal placement of PbtO2 probes. Due to the localized measurement, integration of probe location in the clinical management of ICH patients seems mandatory. It remains unclear if brain oxygenation parameters are representative for the whole brain (most likely in the normal appearing brain tissue on head CT-scan) or data derived from the perilesional brain tissue should be integrated into clinical decision making [6, 30]. In the current study, we could confirm higher rates of BTH in the perilesional brain tissue in the early phase which is in line with previous reports [31]. In ICH patients, the perihemorrhagic area is most vulnerable to secondary brain damage due to the proinflammatory response and other secondary injury cascades [32]. Interestingly, we found that BTH significantly decreased over time in our patients which could reflect a regeneration process of the perihematomal area after ICH [33] or the impact of our PbtO2-based protocol to prevent brain tissue hypoxia [14]. This would support the hypothesis that the perihematomal area may be amenable to treatment. Importantly, there was no significant difference indicating a more aggressive treatment in patients with perilesional probes as compared to those with probes in healthy appearing tissue within the acute phase. Still, we observed more often episodes of intracranial hypertension in patients with perihematomal probe location, although the results did not reach significant levels. Either way, monitoring of PbtO2 in the perihematomal area may open up a novel treatment target in individualized patients in order to prevent further brain injury. Still, our data should be confirmed prospectively to quantify the effect of implementing a PbtO2 guided treatment protocol. Improvement in PbtO2 levels in the perilesional area over time has previously been described in TBI patients [5, 6, 14, 33].

Deleterious effects of BTH are well known in neurocritical care patients [19, 34]. Recently, a Phase III study proved that the time spent in BTH can be significantly reduced when applying a PbtO2-based protocol in TBI patients. Although underpowered to detect an impact on outcome, descriptive outcome analysis seemed promising [18]. In these studies, the location of the PbtO2 probe was not integrated. It is important to mention that the association between BTH and outcome has not been thoroughly studied in ICH patients. We found an overall incidence in BTH of 24%. Interestingly, BTH was only associated with poor functional outcome when measured in the perilesional area, which is consistent with the findings in TBI patients by Ponce et al. [5] and data derived from a swine model [35]. Our results support the placement of PbtO2 probes in the perihematomal tissue, since PbtO2 values obtained in perilesional tissue bear greater prognostic potential than levels measured in normal-appearing tissue. This may be explained by the less frequent occurrence of BTH episodes in healthy brain tissue. Moreover, it might also be that healthy parenchyma is less sensitive to BTH, and therefore, there is a need for different thresholds for BTH than in perilesional location.

There are some limitations that warrant consideration. First, we present a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data. Accordingly, we cannot specify causalities but only associations. Moreover, the patient cohort was a selected group of poor-grade ICH patients requiring HE and invasive neuromonitoring. Consequently, we determined a mRS ≤ 4 to dichotomize outcome. Still, our results describe clinical practice of PbtO2 monitoring in poor-grade ICH patients and may help to better understand data derived from neuromonitoring. Third, there is a limitation grading PbtO2 catheter location by using less sensitive CT scans rather than MRI. As a result, there may be undetected minor ischemic or hemorrhagic lesions that may have affected PbtO2 levels. Although we found that PbtO2 values might be even more relevant in the perilesional tissue for outcome prediction, further studies are needed to investigate the pathophysiologic cascades leading to BTH in the early phase of ICH. Despite the fact we aimed for a perilesional probe location in our patients by placement after HE and by tunneling the devices, this was only achieved in 18/40 patients. There are insufficient data to support an imaging guided procedure, which would facilitate probe location. Even if probe positioning may not be improved, interpretation of absolute PbtO2 levels strongly depend on probe location. Moreover, our data suggest that low PbtO2 levels sincerely matter in the perihematomal brain tissue. Still, more studies are needed to test the hypothesis that a more aggressive treatment to increase PbtO2 levels in the perihematomal area would ameliorate outcome in these patients. Furthermore, in the current study we used a single probe to monitor the oxygen profile in ICH patients and separated the groups depending on neuroimaging results revealing probes either in the perihematomal brain tissue or in normal appearing brain tissue. Our results are supported by a porcine model where 4 concurrent PbtO2 probes were placed in different regions. PbtO2 values were strongly influenced by the distance from the site of focal injury with the lowest values in the perihematomal area [35]. A recommendation for individual patients may not be given based on our results. Still, our data confirm the brain tissue hypoxia in the perihematomal area is important in outcome prediction.

Summary/Conclusions

This observational study indicates that BTH was more common in the perilesional area and has prognostic implications. Furthermore, BTH was more pronounced in the early phase in ICH patients. Our data suggest that PbtO2 values obtained in perilesional tissue bear greater prognostic potential than levels measured in normal-appearing tissue. In addition, these results support the hypothesis that BTH in the perilesional area improves over time and is potentially amenable to treatment.

References

Dornbos Iii D, Powers CJ, Ding Y, Liu L. Neurocritical care in the treatment of stroke. Neurol Res. 2016;38:491–4.

van Asch CJ, Luitse MJ, Rinkel GJ, van der Tweel I, Algra A, Klijn CJ. Incidence, case fatality, and functional outcome of intracerebral haemorrhage over time, according to age, sex, and ethnic origin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:167–76.

Rivera Lara L, Puttgen HA. Multimodality monitoring in the neurocritical care unit. Continuum. 2018;24:1776–888.

Le Roux P, Menon DK, Citerio G, et al. The International Multidisciplinary Consensus Conference on Multimodality Monitoring in Neurocritical Care: a list of recommendations and additional conclusions: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Neurocritical Care Society and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Neurocrit Care. 2014;21(2):282–96.

Ponce LL, Pillai S, Cruz J, et al. Position of probe determines prognostic information of brain tissue PO2 in severe traumatic brain injury. Neurosurgery. 2012;70:1492–502.

Longhi L, Pagan F, Valeriani V, et al. Monitoring brain tissue oxygen tension in brain-injured patients reveals hypoxic episodes in normal-appearing and in peri-focal tissue. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:2136–42.

Morgalla MH, Haas R, Grozinger G, et al. Experimental comparison of the measurement accuracy of the Licox((R)) and Raumedic ((R)) Neurovent-PTO brain tissue oxygen monitors. Acta Neurochirurg Suppl. 2012;114:169–72.

Hemphill JC 3rd, Greenberg SM, Anderson CS, et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American heart association/American stroke association. Stroke. 2015;46:2032–60.

Steiner T, Al-Shahi Salman R, Beer R, et al. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Int J Stroke. 2014;9:840–55.

Alizadeh AM, Hassanian-Moghaddam H, Shadnia S, Zamani N, Mehrpour O. Simplified acute physiology score II/acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II and prediction of the mortality and later development of complications in poisoned patients admitted to intensive care unit. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2014;115:297–300.

Hemphill JC 3rd, Bonovich DC, Besmertis L, Manley GT, Johnston SC. The ICH score: a simple, reliable grading scale for intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2001;32:891–7.

Kothari RU, Brott T, Broderick JP, et al. The ABCs of measuring intracerebral hemorrhage volumes. Stroke. 1996;27:1304–5.

Chesnut R, Aguilera S, Buki A, et al. A management algorithm for adult patients with both brain oxygen and intracranial pressure monitoring: the Seattle international severe traumatic brain injury consensus conference (SIBICC). Intensive care medicine 2020.

Rass V, Solari D, Ianosi B, et al. Protocolized Brain Oxygen Optimization in Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care 2019.

Hemphill JC 3rd, Morabito D, Farrant M, Manley GT. Brain tissue oxygen monitoring in intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2005;3:260–70.

Rose JC, Neill TA, Hemphill JC 3rd. Continuous monitoring of the microcirculation in neurocritical care: an update on brain tissue oxygenation. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2006;12:97–102.

Mulvey JM, Dorsch NW, Mudaliar Y, Lang EW. Multimodality monitoring in severe traumatic brain injury: the role of brain tissue oxygenation monitoring. Neurocrit Care. 2004;1:391–402.

Okonkwo DO, Shutter LA, Moore C, et al. Brain oxygen optimization in severe traumatic brain injury phase-II: a phase II randomized trial. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:1907–14.

Kett-White R, Hutchinson PJ, Al-Rawi PG, Gupta AK, Pickard JD, Kirkpatrick PJ. Adverse cerebral events detected after subarachnoid hemorrhage using brain oxygen and microdialysis probes. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:1213–21.

Haitsma IK, Maas AI. Advanced monitoring in the intensive care unit: brain tissue oxygen tension. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2002;8:115–20.

Rosenthal G, Hemphill JC 3rd, Sorani M, et al. Brain tissue oxygen tension is more indicative of oxygen diffusion than oxygen delivery and metabolism in patients with traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1917–24.

Gaasch M, Schiefecker AJ, Kofler M, et al. Cerebral autoregulation in the prediction of delayed cerebral ischemia and clinical outcome in poor-grade aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage patients. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:774–80.

Czosnyka M, Smielewski P, Piechnik S, Steiner LA, Pickard JD. Cerebral autoregulation following head injury. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:756–63.

Balbi M, Koide M, Wellman GC, Plesnila N. Inversion of neurovascular coupling after subarachnoid hemorrhage in vivo. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2017;37:3625–34.

Coles JP, Fryer TD, Coleman MR, et al. Hyperventilation following head injury: effect on ischemic burden and cerebral oxidative metabolism. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:568–78.

Wang E, Ho CL, Lee KK, Ng I, Ang BT. Effects of temperature changes on cerebral biochemistry in spontaneous intracerebral hematoma. Acta Neurochirurg Supp. 2008;102:335–8.

Schiefecker AJ, Beer R, Pfausler B, et al. Clusters of cortical spreading depolarizations in a patient with intracerebral hemorrhage: a multimodal neuromonitoring study. Neurocrit Care. 2015;22:293–8.

Witsch J, Frey HP, Schmidt JM, et al. Electroencephalographic Periodic Discharges and Frequency-Dependent Brain Tissue Hypoxia in Acute Brain Injury. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:301–9.

Kirkman MA, Smith M. Brain oxygenation monitoring. Anesthesiol Clin. 2016;34:537–56.

Coles JP, Fryer TD, Smielewski P, et al. Incidence and mechanisms of cerebral ischemia in early clinical head injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:202–11.

Ko SB, Choi HA, Parikh G, et al. Multimodality monitoring for cerebral perfusion pressure optimization in comatose patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2011;42:3087–92.

Tobieson L, Ghafouri B, Zsigmond P, Rossitti S, Hillman J, Marklund N. Dynamic protein changes in the perihaemorrhagic zone of Surgically Treated Intracerebral Haemorrhage Patients. Sci Rep. 2019;9:3181.

Siddique MS, Fernandes HM, Wooldridge TD, Fenwick JD, Slomka P, Mendelow AD. Reversible ischemia around intracerebral hemorrhage: a single-photon emission computerized tomography study. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:736–41.

De Georgia MA. Brain tissue oxygen monitoring in neurocritical care. J Intensive Care Med. 2015;30:473–83.

Hawryluk GW, Phan N, Ferguson AR, et al. Brain tissue oxygen tension and its response to physiological manipulations: influence of distance from injury site in a swine model of traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2016;125:1217–28.

Greenberg SM, Rebeck GW, Vonsattel JP, Gomez-Isla T, Hyman BT. Apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 and cerebral hemorrhage associated with amyloid angiopathy. Ann Neurol 1995;38:254–9.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Elisabeth Scherl for data acquisition. Moreover, we would like to thank the nursing staff and the entire team of the intensive care unit for their ongoing contribution in the care of our patients

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Innsbruck and Medical University of Innsbruck. This study has received funding from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) under Project Number KLI 375 (to RB). The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest. Dr. Beer reports grants from Austrian Science Fund (FWF), during the conduct of the study; grants from Austrian Science Fund (FWF), outside the submitted work. Dr. Thomé reports grants and personal fees from BrainLab, grants and personal fees from DePuySynthes, grants and personal fees from Intrinsic Therapeutics, grants from TETEC AG, personal fees from Aesculap, grants and personal fees from Signus Medizintechnik, grants and personal fees from Medtronic, grants and personal fees from Icotec AG, grants and personal fees from Edge Therapeutics, grants from BITPharma, outside the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AL was involved in study idea and design, data acquisition and analysis, manuscript writing and drafting. RH helped in study idea and design, data acquisition and analysis, manuscript writing and drafting. VR, BI, AJS, MK, PR, BP and RB helped in study idea, data acquisition, manuscript drafting. ES was involved in study idea and design, data acquisition, manuscript drafting. CT contributed to study idea and design, manuscript drafting. All authors read and approved this version of the final manuscript and have contributed significantly to the work. The study design was guided by the STROBE statement on observational cohort studies.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study according to local regulations.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lindner, A., Rass, V., Ianosi, BA. et al. The Importance of PbtO2 Probe Location for Data Interpretation in Patients with Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care 34, 804–813 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-020-01089-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-020-01089-w