Abstract

A 44-year-old female patient with a familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) was diagnosed with a cribriform morular thyroid carcinoma (CMTC). We observed within the very necrotic tumor a small but distinct poorly differentiated carcinomatous component. As expected, next generation sequencing of both components revealed a homozygous APC mutation and in addition, a TERT promoter mutation. A TP53 mutation was found exclusively in the CMTC part, while the poorly differentiated component showed a clonal evolution, harboring an activating PIK3CA mutation and copy number gains of BRCA2, FGF23, FGFR1, and PIK3CB—alterations which are typically seen in squamous cell carcinoma. The mutational burden in both components was low, and there was no evidence for microsatellite instability. No mutations involving the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, typically seen in papillary thyroid carcinomas, were detected. Immunohistochemically, all tumor parts were negative for thyroglobulin, providing further evidence that this entity does not belong to the follicular epithelial cell-derived thyroid carcinoma group. CD5 was negative in the poorly differentiated component, making a relation to intrathyroidal thymic carcinoma rather unlikely. However, since this marker was seen in the morules, a loss in the poorly differentiated component and a relation to the ultimobranchial body cannot be excluded either. After total thyroidectomy and radioiodine ablation, the patient was disease-free with no residual tumor burden on 2-year follow-up.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cribriform morular thyroid carcinoma (CMTC) is frequently associated with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and is characterized by a strong female predominance [1]. It has an excellent prognosis and a very distinctive histology with multifocal morules within the neoplasm. Because of this distinctive morphology, it serves as an indicator lesion for FAP which is present in about 40% of CMTC patients and which is much more likely to determine the patient’s fate with multiple colonic adenomas and a very high lifetime risk of progression to invasive colorectal cancer.

This report is, to our knowledge, the first case of a CMTC with morphological and molecular clonal evolution into a poorly differentiated carcinoma with squamoid morphology without invasion into perilesional tissue, and we provide next generation sequencing data of both tumor components with new molecular insights into tumor progression of this rare TC (thyroid carcinoma) variant.

Patient’s Clinical History

A 44-year-old female patient was referred to our thyroid center with a painful left cervical mass. She has a family history of FAP which is genetically confirmed. Nineteen years earlier, she underwent a prophylactic proctocolectomy, which showed no malignancy. There was no positive family history for thyroid or parathyroid disease. Due to hypothyroidism, the patient has been on hormonal substitution therapy with levothyroxine for the past 6 years with stable hormonal function. B-symptoms were denied. On inspection, she had a grade 2 left-sided goiter. Physical examination showed a palpable thyroid nodule which was not tender or indurated without adjacent cervical lymphadenopathy. The patient was euthyroid; serum calcium and calcitonin were in the normal range, and thyroid antibodies were negative. Sonographically, the left thyroid lobe was almost completely filled by a hypoechogenic nodule (EU-TIRADS 4). The right lobe of the thyroid gland was free of nodules. No evidence of lymphadenopathy could be found in the cervicocentral or cervicolateral compartments. Fine-needle aspiration revealed foam cells and blood. No epithelia could be detected. The findings were consistent with cystic fluid (Bethesda category I). Initially, a left hemithyroidectomy was performed without complications.

After obtaining the definite histological results and collecting international expert opinions, the case was extensively discussed at our interdisciplinary tumor board for endocrine malignancies. The recommendation was made for staging by whole-body FDG-PET-CT and subsequent completion thyroidectomy as well as adjuvant radioiodine therapy which was performed without complications. Whole-body FDG-PET-CT showed no local or distant metastases. Postoperatively, the patient had normal serum calcium and parathyroid hormone values and a normal phoniatrical evaluation. No further malignant tissue was found in the final histology. After completion of wound healing, adjuvant radioiodine therapy with 1958 MBq iodine 131 under exogenous stimulation was performed 4 weeks postoperatively. Thyroid hormone substitution was continued and adjusted (TSH goal 0.5–2.0 mU/L). At the first follow-up, 6 months postoperatively, clinical examination, sonography, posttreatment whole-body radioiodine scan, and partial body PET/CT with 274 MBq 18F-FDG showed no evidence of local recurrence in the thyroid bed, suspicious lymph nodes, or distant metastases. The patient had a TSH-stimulated thyroglobulin of < 1 ng/mL. The last follow-up, 2 years postoperatively, including physical examination, non-stimulated serum thyroglobulin, and imaging showed a persisting excellent response to initial therapy (Fig. 1a and b).

Materials and Methods

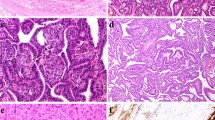

Reference histology showed a 3-cm largely necrotic tumorous mass. In the vital parts, the classic hallmarks of CMTC were seen including complex architecture with cribriform and squamoid morulae without colloid formation [1, 2]. Immunohistochemistry showed TTF1 (Clone SPT24, Novocastra, cat-nr.:NCL-L-TTF1) and estrogen receptor positivity and diffuse nuclear accumulation of beta-catenin and a negativity for PAX-8 (polyclonal, Proteintech, cat-nr.: 10,336–1-AP) and thyroglobulin, the squamoid morules were positive for CD10 and negative for TTF1, estrogen receptor, PAX-8 and thyroglobulin (Fig. 2, Table 1). More important, there was a small but very unique second tumor component of a poorly differentiated carcinoma. No evidence of lymphatic or vascular invasion was found. Both tumor parts were sequenced using Illuminas true sight oncology 500 (TSO500) panel on DNA and RNA level. There was a homozygous APC mutation in both tumor parts with a high allelic frequency, consistent with the diagnosed FAP of the patient. A TERT promoter mutation was also identified in both tumor areas. A TP53 mutation was found exclusively in the CMTC part. The poorly differentiated carcinoma only harbored an activating PIK3CA mutation and copy number gains of BRCA2, FGF23, FGFR1, and PIK3CB (Table 2). The mutational burden in both components was 3.9 mutations per megabase, and there was no evidence for microsatellite instability (instability in 2 of 125 microsatellites). Of note, a metastasis of a squamous cell carcinoma primary into the CMTC was ruled out clinically and on molecular grounds since it shared some mutations with the CMTC.

Left side, well-differentiated CMT component, 20 × magnification, right side poorly differentiated areas, 30 × magnification. First row HE. Second row TTF1, note negativity in the morules. Third row left: CD 5, with positivity in morules, negativity in the poorly differentiated areas (not shown). Third row right: p40, strong nuclear positivity in poorly differentiated areas. Forth row left: CD10 partial positivity in morules. Forth row right: increased Ki-67 in poorly differentiated areas. Fifth row: strong cytoplasmic and nuclear b-catenin staining in both areas

Discussion

Until recently, CMTC was thought to be a part of the spectrum of papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC), and this is the reason why old papers list CMTC together with PTC [3]. However, new research data showed convincing evidence that CMTC is a distinct entity [2, 4].

CMTC is very rare—it occurs in only about 0.5% of all TC [5, 6]. This variant is known to occur almost exclusively in females, and it is known for a very favorable outcome [3, 4, 7, 8]. A large series of 30 CMTCs out of 17,062 PTC cases found only one patient with a local recurrence in the remaining thyroid, while all other patients were tumor-free in their long-term follow-up. Therefore, the authors did not recommend lymph node dissection in these patients [8]. It is nevertheless important to recognize this entity for pathologists and clinicians alike since it may serve as an indicator lesion for FAP, which was also present in our patient [8].

Patients with FAP frequently harbor germline mutations in APC, which causes activation of the Wnt signaling pathway. In the case of sporadic CMTC, this pathway can also be activated by somatic APC mutations or mutations in CTNNB1. As a consequence, β-catenin shows immunohistochemically an aberrant nuclear expression, especially in the squamoid morules, a fact that is used as an immunohistochemical diagnostic hallmark for this tumor [1, 2, 8].

The cell of origin for CMTC is still unknown. This tumor is never immunohistochemically positive for markers expressed by all other tumors derived from the follicular epithelial cell like thyroglobulin or PAX8. The immunohistochemical profile reported in the largest series of CMTC with different expression of various markers in the cribriform component and the morules are also recapitulated by the tumor presented here—at least in the well-differentiated component and the morules.

Typical PTC frequently harbors activating mutations of genes in the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, which are the main driver of tumorigenesis. These include BRAF and RAS mutations or CCDC6::RET and NCOA4::RET fusions [9]. In contrast, no BRAF mutation was found in a series of 17 CMTC, and only one KRAS mutation was reported in 7 cases [10]. The present case also had none of these mutations, providing further evidence that CMTC is a distinct neoplasm.

The differential diagnosis for the poorly differentiated component was a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), a carcinoma arising in morules with squamous metaplasia or an intrathyroidal thymic carcinoma. Morphologically and immunohistochemically, it would best fit the diagnosis of poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) because of strong nuclear positivity of p40, a marker considered very sensitive for differentiating SCC [11]. Staining for CD5 and CK5 was negative, with the latter marker being negative in approximately 5% of SCC, arguing against the diagnosis of SCC [12]. This component was seen within the CMTC without extension or invasion into the surrounding thyroid tissue and was therefore considered non-invasive, analogous to the diagnostic criteria for higher-grade TC. The possibility that the poorly differentiated component originated in ultimobranchial pouch-related cellular components, as discussed by Boyraz et al., and subsequently lost the typical morular immunophenotype, cannot be excluded and may be supported by an absence of CK5 expression [4].

The PI3K/Akt pathway plays an important role in the tumorigenesis of thyroid cancer [13], and two of the genes we identified in the poorly differentiated carcinoma component, PIK3CA and PIK3CB, belong to this pathway. However, PIK3CA mutations are rare in PTC, accounting for only 2% of cases, and to our knowledge have not been observed in CMTC. FGFR1 copy number increases were also not detected in PTC or other thyroid carcinomas [14, 15].

In contrast, PIK3CA mutations and copy number gains of components of FGFR signaling pathway have been described as oncogenic drivers of squamous cell carcinoma of different origin including lung, head and neck, and stomach [16]. Therefore, we can speculate that the acquisition of these changes may have triggered the squamous morphology.

The molecular alterations just mentioned must have arisen in a subclone of CMTC prior to the acquisition of the TP53 mutation, thereby progressing into a poorly differentiated carcinoma. TP53 mutations are usually associated with an aggressive nature of the tumor being most common in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma [17, 18]. However, the TP53 mutation was identified in the well-differentiated tumor area of CMTC only. The reason for this is unknown but may be explained by the different genetic background of both components. To date, no TP53 mutations have been reported in CMTC [19].

The CMTC and the poorly differentiated cell component share a common mutation in the TERT promoter, indicating that they are derived from the same cell of origin. Interestingly, TERT promoter mutations were observed in a subset (22%) of intrathyroidal thymic carcinomas [20]. These mutations are strongly associated with an adverse clinical outcome in thyroid carcinomas [21, 22]. One publication reported a TERT promoter mutation in a patient with CMTC with local and distant metastases [10], consistent with the adverse outcome associated with TERT promoter mutations [19]. Furthermore, progression into a poorly differentiated TC with an adverse outcome including local and distant metastases has been very rarely reported in CMTC [23]. The aggressive morphology of the carcinoma component on the one hand and the presence of the TERT mutation on the other hand indicate a rather unfavorable prognosis of the patient.

Moreover, the new 2022 WHO classification of endocrine organs lists primary squamous cell carcinoma in the thyroid gland as part of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma [1]. However, the poorly differentiated component was encapsulated, and applying general pathologic diagnostic rules, the diagnosis of this tumor part does not qualify as poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma according to the Turin classification or as anaplastic thyroid carcinoma, because of the absence of unequivocal invasive features [24,25,26]. Nevertheless, this reflects a cytomorphologically aggressive part, also underscored by the high proliferation index. A similar situation is described in thyroid tumors of follicular cell origin harboring areas of poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma without invasion, and these tumors did not recur over a 10-year period [27]. In line with this, our patient had no evidence of local or distant metastatic spread after a 2-year follow-up. Thus, the clinical significance of genetic alterations of the CMTC case described here remains to be seen.

Conclusion

We report a rare case of a CMTC with a poorly differentiated tumor component with squamous cell morphology. Next-generation sequencing revealed an APC mutation and a TERT promoter mutation in both tumor parts with the former being associated with the underlining FAP, the latter being potentially associated with an adverse outcome. In addition, the poorly differentiated component harbored mutations like PIK3CA and PIK3CB and an amplification in FGFR1, supporting evidence in conjunction with immunohistochemistry and conventional morphology of squamous cell morphology. The cell of origin of this component and whether this reflects an ultimobranchial pouch-related cellular component remain unclear. The patient was treated with total thyroidectomy and radioiodine ablation. On 2-year follow-up, she was disease-free with no clinical, biochemical, or structural evidence identified on risk-appropriate follow-up studies [28,29,30].

Availability of Data and Materials

Not applicable.

References

WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Endocrine and neuroendocrine tumours [Internet; beta version ahead of print]. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2022 [cited 2023–05–02]. (WHO classification of tumours series, 5th ed.; vol. 10). Available from: https://tumourclassification.iarc.who.int/chapters/53.

Baloch ZW, Asa SL, Barletta JA, Ghossein RA, Juhlin CC, Jung CK, LiVolsi VA, Papotti MG, Sobrinho-Simoes M, Tallini G, Mete O Overview of the 2022 WHO Classification of Thyroid Neoplasms. Endocr Pathol 2022 Mar;33(1):27-63.

Lloyd RYO, Klöppel G, Rosai J WHO Classification of Tumours of Endocrine Organs. (IARC, 2017) (4th ed).

Boyraz B, Sadow PM, Asa SL, Dias-Santagata D, Nose V, Mete O. Cribriform-Morular Thyroid Carcinoma Is a Distinct Thyroid Malignancy of Uncertain Cytogenesis. Endocr Pathol 2021 Sep;32(3):327-335.

Hirokawa M, Maekawa M, Kuma S, Miyauchi A Cribriform-morular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma-Cytological and immunocytochemical findings of 18 cases. Diagn Cytopathol, 2010 Dec;38(12):890-6.

Tomoda C, Miyauchi A, Uruno T, Takamura Y, Ito Y, Miya A, Kobayashi K, Matsuzuka F, Kuma S, Kuma K, Kakudo K Cribriform-morular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: clue to early detection of familial adenomatous polyposis-associated colon cancer. World J Surg 2004 Sep;28(9):886-9.

Lam A K, Saremi N Cribriform-morular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: a distinctive type of thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 2017 Apr;24(4):R109-R121.

Akaishi J, Kondo T, Sugino K, Ogimi Y, Masaki C, Hames KY, Yabuta T, Tomoda C, Suzuki A, Matsuzu K, Uruno T, Ohkuwa K, Kitagawa W, Nagahama M, Katoh R, Ito K Cribriform-Morular Variant of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma: Clinical and Pathological Features of 30 Cases. World J Surg 2018; 42, 3616-3623.

Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N. Integrated genomic characterization of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cell 2014 Oct 23;159(3):676–90.

Oh EJ, Lee S, Bae JS, Kim Y, Jeon S, Jung CK TERT Promoter Mutation in an Aggressive Cribriform Morular Variant of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. Endocr Pathol 2017 Mar;28(1):49-53.

Bishop JA, Teruya-Feldstein J, Westra WH, Pelosi G, Travis WD, Rekhtman N p40 (DeltaNp63) is superior to p63 for the diagnosis of pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol 2012 Mar;25(3):405-15.

Volkel C, De Wispelaere N, Weidemann S, Gorbokon N, Lennartz M, Luebke AM, Hube-Magg C, Kluth M, Fraune C, Moller K, Bernreuther C, Lebok P, Clauditz TS, Jacobsen F, Sauter G, Uhlig R, Wilczak W, Steurer S, Minner S, Krech RH, Dum D, Krech T, Marx AH, Simon R, Burandt E, Menz A Cytokeratin 5 and cytokeratin 6 expressions are unconnected in normal and cancerous tissues and have separate diagnostic implications. Virchows Arch 2022 Feb;480(2):433-447.

Zhu J, Wu K, Lin Z, Bai S, Wu J, Li P, Xue H, Du J, Shen B, Wang H, Liu Y Identification of susceptibility gene mutations associated with the pathogenesis of familial nonmedullary thyroid cancer. Mol Genet Genomic Med 2019 Dec;7(12):e1015.

von Loga K, Kohlhaussen J, Burkhardt L, Simon R, Steuerer S, Burdak-Rothkamm S, Jacobsen F, Sauter G, Krech T FGFR1 Amplification Is Often Homogeneous and Strongly Linked to the Squamous Cell Carcinoma Subtype in Esophageal Carcinoma. PLoS One 2015 Nov 10;10(11):e0141867.

Willis O, Choucair K, Alloghbi A, Stanbery L, Mowat R, Charles BF, Dworkin L, Nemunaitis J PIK3CA gene aberrancy and role in targeted therapy of solid malignancies. Cancer gene therapy 2020 Sep;27(9):634-644.

Alqahtani A, Ayesh HSK, Halawani H PIK3CA Gene Mutations in Solid Malignancies: Association with Clinicopathological Parameters and Prognosis. Cancers (Basel) 2019 Dec 30;12(1):93.

Nikiforov YE, Nikiforova MN Molecular genetics and diagnosis of thyroid cancer. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2011 Aug 30;7(10):569-80.

Dettmer MS, Schmitt A, Komminoth P, Perren A Poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma : An underdiagnosed entity. Pathologe 2020 Jun;41(Suppl 1):1-8.

Cameselle-Teijeiro JM, Peteiro-Gonzales D, Caneiro-Gomez J, Sanchez-Ares M, Abdulkader I, Eloy C, Melo M, Amendoeira I, Soares P, Sobrinho-Simoes M Cribriform-morular variant of thyroid carcinoma: a neoplasm with distinctive phenotype associated with the activation of the WNT/beta-catenin pathway. Mod Pathol 2018 Aug;31(8):1168-1179.

Tahara I, Oishi N, Mochizuki K, Oyama T, Miyata K, Miyauchi A, Hirokawa M, Katoh R, Kondo T Identification of Recurrent TERT Promoter Mutations in Intrathyroid Thymic Carcinomas. Endocr Pathol 2020 Sep;31(3):274-282.

Dettmer MS, Schmitt A, Steinert H, Capper D, Moch H, Komminoth P, Perren A Tall cell papillary thyroid carcinoma: new diagnostic criteria and mutations in BRAF and TERT. Endocr Relat Cancer 2015 Jun;22(3):419-29.

Liu R, Xing M TERT promoter mutations in thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 2016 Mar;23(3):R143-55.

Kusum L Sharma RBS, Nisreen F, Ricardo VL Cribriform-morular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma with poorly differentiated features: report of a case and review of the literature. Surg Exp Pathol 2022; 5, 1.

Dettmer M, Schmitt A, Steinert H, Haldemann A, Meili A, Moch H, Komminoth P, Perren A Poorly differentiated thyroid carcinomas: how much poorly differentiated is needed? Am J Surg Pathol 2011 Dec;35(12):1866-72.

Dettmer M, Schmitt A, Steinert H, Moch H, Komminoth P, Perren A Poorly differentiated oncocytic thyroid carcinoma--diagnostic implications and outcome. Histopathology 2012 Jun;60(7):1045-51.

Volante M, Collini P, Nikiforov YE, Sakamoto A, Kakudo K, Katoh R, Lloyd RV, LiVolsi VA, Papotti M, Sobrinho-Simoes M, Bussolati G, Rosai J Poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma: the Turin proposal for the use of uniform diagnostic criteria and an algorithmic diagnostic approach. Am J Surg Pathol 2007 Aug;31(8):1256-64.

Rivera M, Ricarte-Filho J, Patel S, Tuttle M, Shaha A, Shah JP, Fagin JA, Ghossein RA Encapsulated thyroid tumors of follicular cell origin with high grade features (high mitotic rate/tumor necrosis): a clinicopathologic and molecular study. Hum Pathol 2010 Feb;41(2):172-80.

Patel KN, Yip L, Lubitz CC, Grubbs EG, Miller BS, Shen W, Angelos P, Chen H, Doherty GM, Fahey TJ 3rd, Kebebew E, Livolsi VA, Perrier ND, Sipos JA, Sosa JA, Steward D, Tufano RP, McHenry CR, Carty SE The American Association of Endocrine Surgeons Guidelines for the Definitive Surgical Management of Thyroid Disease in Adults. Ann Surg 2020 Mar;271(3):e21-e93.

Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, Doherty GM, Mandel SJ, Nikiforov YE, Pacini F, Randolph GW, Sawka AM, Schlumberger M, Schuff KG, Sherman SI, Sosa JA, Steward DL, Tuttle RM, Wartofsky L 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid 2016 Jan;26(1):1-133.

Dralle H, Musholt TJ, Schabram J, Steinmuller T, Frilling A, Simon D, Goretzki PE, Niederle B, Scheuba C, Clerici T, Hermann M, Kussmann J, Lorenz K, Nies C, Schabram P, Trupka A, Zielke A, Karges W, Luster M, Schmid KW, Vordermark D, Schmoll HJ, Muhlenberg R, Schober O, Rimmele H, Machens A German Association of Endocrine Surgeons practice guideline for the surgical management of malignant thyroid tumors. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2013 Mar;398(3):347-75.

Acknowledgements

We thank the technicians of the Clinical Genomics Lab Inselspital for excellent technical assistance.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Bern.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Matthias S. Dettmer and Aurel Perren made the diagnosis and wrote the manuscript. Erik Vassella performed NGS and analyzed molecular data. Sandra Hürlimann, Lukas Scheuble, and Corinna Wicke provided clinical data. All authors read and approved the final document.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

A patient consent was obtained, appropriate processes have been followed, and the study was approved by the Cantonal Research Ethics Board (KEK Bern ID 2018–01657).

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Aurel Perren and Corinna Wicke share last authorship.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dettmer, M.S., Hürlimann, S., Scheuble, L. et al. Cribriform Morular Thyroid Carcinoma – Ultimobranchial Pouch-Related? Deep Molecular Insights of a Unique Case. Endocr Pathol 34, 342–348 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12022-023-09775-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12022-023-09775-z