Abstract

Purpose

Sirtuin 1 may regulate glucose and lipid metabolism. We aimed to assess adipose tissue and skeletal muscle sirtuin 1 expression in relation to insulin sensitivity, the expression of proinflammatory and metabolic genes, and to study the regulation of sirtuin 1 expression by hyperinsulinemia and circulating free fatty acids elevation.

Methods

We examined 60 normal-weight, 42 overweight and 15 obese young subjects. The hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp technique was applied throughout to measure insulin sensitivity. In 20 subjects, two 6 h clamps were performed, one of them with concurrent Intralipid/heparin infusion. Biopsies of subcutaneous adipose tissue and skeletal muscle were collected for the measurement of gene and protein expression.

Results

Obese subjects had lower adipose sirtuin 1 in comparison with normal-weight and overweight participants. Muscle sirtuin 1 did not differ between the groups. Adipose tissue sirtuin 1 was related to insulin sensitivity, adipose tissue SLC2A4. The relationship between adipose tissue sirtuin 1 and insulin sensitivity was still present after controlling for BMI, however, it disappeared after controlling for adipose tissue SLC2A4. Muscle sirtuin 1 was not related to insulin sensitivity. Hyperisulinemia decreased adipose tissue and increased muscle sirtuin 1 expression. Intralipid/heparin infusion negated these effects.

Conclusions

Adipose tissue, but not muscle, sirtuin 1 is associated with insulin sensitivity in humans, possibly because of its correlation with adipose tissue SLC2A4 expression. Insulin differentially regulates adipose tissue and skeletal muscle sirtuin 1 expression in the short-term and circulating free fatty acids elevation negates these effects, which may be associated with lipid-induced insulin resistance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), is a (NAD)-dependent deacetylase, a member of the sirtuin family [1]. SIRT1 can deacetylate many histone and nonhistone proteins. Therefore, it is involved in the regulation of multiple physiological processes, including substrate metabolism [1, 2].

SIRT1 may influence insulin signaling in multiple insulin sensitive cells [3]. It increases insulin receptor substrate 2 (IRS2) and protein kinase B (PKB, known as Akt) phosphorylation in response to insulin whereas it decreases the expression of protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B), a negative regulator of insulin signalling [4,5,6].

Some studies indicate that SIRT1 enhances insulin signalling at least in part because of its antiinflammatory effects in AT. SIRT1 overexpression prevents macrophage accumulation caused by high-fat feeding [7]. SIRT1 represses proinflammatory gene expression in adipocytes, possibly through nuclear factor κB (NFκB) deacetylation and inhibition of binding to its target gene promoters [8]. It also increases adiponectin synthesis/secretion [9].

SIRT1 may also influence skeletal muscle metabolism through deacetylation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1-α (PGC1-α), a mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation activator [10].

In the context of the above data, it was hypothesized that SIRT1 influences insulin sensitivity [11] and may be a therapeutic target in the prevention and treatment of disorders related to insulin resistance [9, 12, 13]. Resveratrol, a SIRT1 activator, had a protective effect against diet-induced insulin resistance in mice [5, 14] and decreased plasma glucose and triglycerides, homeostatic model assessment (HOMA) index and inflammation markers in humans with obesity [15]. However, in the studies with SIRT1 overexpression in multiple tissues in mice, both improved and unchanged glucose tolerance was observed [16, 17].

It remains unclear as to what the possible mechanism of beneficial SIRT1 action is on insulin sensitivity and which tissue is its major target. Furthermore, human data on the potential relationships of SIRT1 expression in different tissues with insulin sensitivity, especially with simultaneous assessment of SIRT1 in adipose tissue and muscle, are very limited.

Therefore, we aimed to assess AT and skeletal muscle SIRT1 expression in young male subjects in relation to body weight, insulin sensitivity; tissue SLC2A4 (encoding GLUT4), AT proinflammatory gene and ADIPOQ and muscle PGC1A expression. We also examined the regulation of tissue SIRT1 expression by hyperinsulinemia and circulating free fatty acids (FFA) elevation.

Materials and methods

Study groups

We examined 117 healthy young men (aged between 18 and 35 years), 60 normal-weight, 42 overweight, and 15 with obesity. The exclusion criteria were: morbid obesity, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, infection or any other serious medical problem, smoking or the taking of drugs known to affect glucose or lipid metabolism. All participants had normal glucose tolerance according to World Health Organization criteria. All examinations were performed after an overnight fast. Body weight had been stable for at least the previous 3 months. Anthropometric and laboratory measurements were performed as described [18, 19].

The Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Białystok, Białystok, Poland, approved the study protocol. All participants gave written informed consent before entering the study.

Insulin sensitivity

A 2 h hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp was applied to assess insulin sensitivity [18]. Additionally, in 20 subjects, two 6 h clamps were performed, one of them with Intralipid/heparin infusion as previously described [19].

Muscle and AT biopsies

Before the clamp, a vastus lateralis muscle and subcutaneous AT biopsy was performed. In a subgroup of 20 individuals, tissue biopsies were collected both before and after each clamp [19].

Gene expression analysis

RNA isolation from tissues was performed as previously described [19]. SIRT1 and SLC2A4 mRNA expression in AT and skeletal muscle; IL18, CCL2, IKBKB, NFKB1, NFKB2, RELA, MAPK8, and ADIPOQ expression in AT and PGC1A mRNA expression in skeletal muscle was measured with Real Time PCR, using the Light Cycler® 480 II system (Roche Diagnostics GmbH) and Software release 1.5.0 SP3. Each sample was measured in triplicate. We used beta-2 microglobulin (B2M) or phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (PGK1) expression as a reference gene in muscle and AT, respectively. Primer sequences are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Western blot

Muscle lysates were prepared by tissue homogenization in a RIPA buffer (R0278, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) with added protease (PMSF, P7626, and Protease Inhibitor Cocktail P8340; Sigma-Aldrich) and phosphatase inhibitors (Pierce Phosphatase Inhibitor Mini Tablets 88,667; Thermo Fisher Scientific), and incubated for 1 h on ice. Thereafter samples were centrifuged and supernatants collected. Adipose tissue samples were prepared according to the manufacturer’s guidelines using the NucleoSpin®RNA/Protein Kit protocol (Macherey-Nagel GmbH, Duren, Germany). BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to determine protein concentration.

Samples were loaded into SDS-10% polyacrylamide gels. After electrophoresis proteins were transferred from the gel onto PVDF (polyvinylidene fluoride) membranes under wet conditions (30 V overnight at 4 °C). Membranes were blocked in Odyssey Blocking Buffer (TBS, LI-COR, Lincoln, NE) for 3 h at room temperature. Primary antibodies were carried out overnight at 4 °C with anti-SIRT1 (1:500, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and anti-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (1:2000, Abcam). After thoroughly washing for 60 min with TBST 0.1% (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), the membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibodies (1:5000, Abcam) for 1 h at room temperature. After re-washing the membranes, immunodetection and visualization of proteins were performed on a ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad) using chemiluminescent substrate detection reagent (ECL, Bio-Rad). GAPDH protein expression from parallel runs was used for the normalization of results.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the STATISTICA 12.5 Program (Statsoft, Krakow, Poland). Where variables did not have normal distribution, log-transformed values were used in the analyses. These variables were again anti-log-transformed to absolute values in the results for the purpose of data presentation. To analyze differences between the groups, one-way ANOVA and Tukey post-hoc tests were used. Differences before and after each clamp and between the 6 h clamps were assessed with Student’s t-test for paired samples. Correlations between variables were determined with the Pearson product-moment correlation and with multiple regression analysis. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Subjects with overweight and obesity had higher fasting serum insulin and total cholesterol (all p < 0.05) than subjects in the normal-weight group. Additionally, subjects with obesity had higher LDL-cholesterol and triglycerides and lower HDL-cholesterol (all p < 0.05) than normal-weight subjects. Insulin sensitivity was similar in the normal-weight and overweight groups whereas subjects with obesity had lower insulin sensitivity in comparison to normal-weight and overweight participants (both p < 0.05) (Table 1).

AT and muscle gene expression

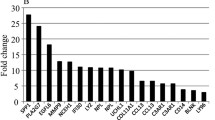

AT SIRT1 expression was lower in obese subjects than in normal-weight and overweight subjects (both p < 0.05) (Fig. 1a). Muscle SIRT1 was not different among the study groups (Fig. 1b).

IL18 and CCL2 AT expression was higher whereas SLC2A4 and ADIPOQ AT expression was lower in the obese than in normal-weight and overweight subjects (all p < 0.05, ADIPOQ only vs. normal-weight subjects). AT IKBKB was lower in the overweight and obese groups than in the normal-weight group (both p < 0.05) (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, in the obese group lower muscle SLC2A4 in comparison to the normal weight and overweight groups and lower PGC1A (all p < 0.01) in comparison to the normal-weight group was observed (Fig. 2b).

Correlations of tissue SIRT1 expression with other parameters

AT SIRT1 expression was related to BMI, waist, percent of body fat, total cholesterol, triglycerides (r values between −0.23 and −0.29, all p < 0.05) and HDL cholesterol (r = 0.35, p < 0.001). We also demonstrated the correlation between AT SIRT1 and M (r = 0.35, p = 0.0003; Fig. 3a). Furthermore, AT SIRT1 was related to AT SLC2A4 (r = 0.41, p < 0.0001; Fig. 3b), but not to inflammatory gene and ADIPOQ expression. Association between AT SIRT1 and insulin sensitivity was still significant after controlling for BMI (β = 0.31, p = 0.006), whereas the correlation of AT SIRT1 with BMI lost its significance after adjustment for M (β = −0,12, p = 0.22). However, the relationship between AT SIRT1 and insulin sensitivity lost its significance after controlling for AT SLC2A4 (β = 0.19, p = 0.053).

There was no correlations between muscle SIRT1 and BMI, insulin sensitivity (Fig. 3c) and other clinical and biochemical parameters studied, however, we observed positive associations with muscle SLC2A4 (r = 0.27; p = 0.006; Fig. 3d) and PGC1A (r = 0.20; p = 0.037). Muscle SIRT1 was not related to AT SIRT1 expression.

Tissue protein expression

Due to the limited amount of tissue available, SIRT1 protein expression was measured in 10 AT (five from normal-weight and five from obese subjects) and eight muscle samples (four from normal-weight and four from obese subjects) in baseline conditions only. Both AT (r = 0.79, p = 0.007) and muscle (r = 0.80, p = 0.017) SIRT1 protein was strongly related to the respective mRNA expression.

AT SIRT1 protein was lower in obese subjects than in normal-weight subjects (p = 0.013, Fig. 4a) and was associated with M (r = 0.70, p = 0.023). Muscle SIRT1 protein was not different between the groups (p = 0.70, Fig. 4b). No correlation of muscle SIRT1 protein with M value was found (r = −0.37, p = 0.38).

SIRT1 expression in AT and muscle after 6 h clamp without and with Intralipid/heparin infusion

Hyperinsulinemia decreased SIRT1 expression in AT by approx. 20% (p = 0.046). Subgroup analysis revealed that this effect was due to the change observed in the normal-weight group (n = 9, p = 0.046; Fig. 5a). The change in SIRT1 after hyperinsulinemia (ΔSIRT1) differed between normal-weight and obese subjects (p = 0.021).

In contrast, muscle SIRT1 expression increased after hyperinsulinemia (p = 0.016) in the entire study group. In subgroup analysis, this effect was observed mainly in the participants with obesity (n = 4, p = 0.013). However, muscle SIRT1 expression increased in response to insulin also in seven out of nine normal-weight subjects, where it approached the level of significance (p = 0.09) and in five out of seven overweight subjects (Fig. 5b). In consequence, ΔSIRT1 in response to insulin in skeletal muscle was not different between the study groups.

Intralipid/heparin infusion resulted in a more than fourfold rise of circulating FFA (p < 0.0001). Insulin sensitivity decreased by approx. 40% during the 6th hour of the clamp (p < 0.0001). No change in AT and skeletal muscle SIRT1 expression was observed after Intralipid/heparin infusion (Fig. 5a, b).

Discussion

In the present study we found that AT, but not skeletal muscle, SIRT1 expression is decreased in obesity and is positively related to whole-body insulin sensitivity. We found that the relationship between AT SIRT1 and SLC2A4 explains the correlation of the former with whole-body insulin sensitivity. Furthermore, we observed that 6 h hyperinsulinemia decreased AT and increased skeletal muscle SIRT1 expression and that both effects were negated by concurrent Intralipid/heparin infusion.

Our data indicate that AT SIRT1 may be important for obesity-associated insulin resistance. Decreased AT SIRT1 expression in obesity had also been reported in other human studies [20,21,22,23,24,25]. In some, obese subjects had BMI in the range of morbid obesity [22], whereas in others [20, 21] mean BMI was similar to the value observed in our obese group. Thus, it is interesting to note that overweight subjects in our study had an AT SIRT1 expression comparable with those in the normal-weight group, which suggests that there could be a threshold associated with body fat accumulation, which determines a decrease in AT SIRT1. Our results suggest that such threshold may be associated with insulin resistance as overweight subjects had normal insulin sensitivity, which may be due to their young age. The relationship between AT SIRT1 and indirect indices of insulin sensitivity [20, 21, 23] and the values from the clamp study in subjects with a family history of type 2 diabetes [26] was also observed by other researchers. In subjects with morbid obesity, decreased AT SIRT1 was observed in the insulin resistant vs. insulin sensitive group [27]. We demonstrated that insulin sensitivity, and not BMI, was an independent predictor of AT SIRT1, whereas such analysis has not been reported in other studies.

Surprisingly, no differences in muscle SIRT1 was found among the study groups. Individuals with type 2 diabetes had lower muscle SIRT1 protein compared to control subjects [4]. However, such difference may be secondary to diabetic conditions, as it was demonstrated in C2C12 myocytes that high glucose significantly reduces the number of SIRT1-positive nuclei and total cellular SIRT1 protein content [28].

We also did not observe any correlations between muscle SIRT1 and metabolic parameters. Although muscle SIRT1 was positively related to muscle SLC2A4 and PGC1A expression, these associations did not seem to influence whole-body insulin sensitivity. Both increased and unchanged insulin-stimulated activation of Akt was observed in cultured myotubes with SIRT1 overexpression [4, 5]. Furthermore, studies with muscle-specific SIRT1 overexpression in rodents showed that it did not enhance insulin-stimulated muscle glucose uptake [29,30,31]. These data indicate that SIRT1 activation in tissues other than muscle may be important for modulating insulin action. Our data on the relationship between AT, but not skeletal muscle, SIRT1 expression with insulin sensitivity, fall in line with this hypothesis.

Rutanen et al. [26] observed a correlation between AT SIRT1 mRNA expression and insulin sensitivity in subjects with a family history of type 2 diabetes. They suggested that results obtained in AT reflected metabolic changes in skeletal muscle, as they observed positive correlation between AT and muscle SIRT1 expression in a small subgroup of their study subjects (n = 11) [26]. Although our results are generally in agreement with those of Rutanen et al. regarding positive correlation between AT SIRT1 mRNA and insulin sensitivity, they do not support the hypothesis about the role of skeletal muscle SIRT1 in determining insulin action. We also did not observe any correlation between AT and muscle SIRT1 expression. This indicates that AT SIRT1 associates with whole-body insulin sensitivity without any relation to muscle SIRT1. In our study AT SIRT1 was also not related to the local proinflammatory gene and ADIPOQ expression.

We found correlation between AT SIRT1 and AT SLC2A4 expression and this association explained the relationship between AT SIRT1 and whole-body insulin sensitivity. SIRT1 knock down in adipocytes led to a decrease in GLUT4 translocation and glucose uptake after stimulation with insulin [8]. AT accounts only for a small fraction of whole-body glucose disposal, however, it was demonstrated that AT-specific GLUT4 depletion resulted in profound metabolic abnormalities, including muscle and liver insulin resistance [32]; whereas AT GLUT4 overexpression in mice with muscle GLUT4 knockout increased muscle glucose uptake [33]. The results of other studies that in part were similar to our own, also demonstrated a decreased ATSLC2A4 expression in animal models of type 2 diabetes [34] and in insulin-resistant humans [33], which may serve to support our findings. Thus, SIRT1 may influence insulin sensitivity through its effect on adipose tissue GLUT4 expression. However, the cause-effect relationship cannot be established on the basis of our data and it is also possible that lower AT SIRT1 expression in obesity may be an effect of hyperinsulinemia, as discussed below.

We next examined the effect of hyperinsulinemia and circulating FFA elevation on tissue SIRT1 expression. In AT, hyperinsulinemia resulted in a decrease in SIRT1. AT SIRT1 increased in response to fasting [22] and weight loss [35], where a decrease in fasting insulin was also observed, however, no correlation between these changes was reported. On the other hand, an increase in AT SIRT1 in response to weight loss without significant change in serum insulin was also observed [20]. It was demonstrated that SIRT1 expression in various tissues, including fat, increased after caloric restriction in rats, and that insulin attenuated this response [36]. To our knowledge, AT SIRT1 expression after hyperinsulinemia in humans has hitherto not been reported. Insulin stimulates adipogenesis and inhibits lipolysis, whereas SIRT1 exerts opposite effects, so the decrease in SIRT1 expression after insulin infusion might be important for the maintaining of adipocyte differentiation and function. It is interesting to note that this effect was present only in the normal-weight group. It is possible that mild prolonged hyperinsulinemia observed in obesity has already led to a decrease in AT SIRT1 expression in the obese group and thus our experimental hyperinsulinemia did not promote any additional effect. We did not observe a decrease in AT SIRT1 in response to insulin in the overweight group, despite baseline SIRT1 and insulin sensitivity comparable to the normal-weight group. One may hypothesize that lack of response of AT SIRT1 to insulin represents an early metabolic abnormality in this group, even before the onset of overt insulin resistance, measured as a decreased insulin-stimulated glucose uptake.

FFA elevation, obtained by Intralipid/heparin infusion, negated the insulin effect on AT SIRT1. This negation of insulin effect may seem paradoxical, when we take into account that a high-fat diet decreases AT SIRT1 [37], however, it may reflect insulin-desensitizing action of FFA and may indicate that AT SIRT1 response contributes to FFA-induced insulin resistance.

Muscle SIRT1 expression increased after hyperinsulinemia. This effect was mostly expressed in the group with obesity, however, a similar tendency was also present in other groups. Insulin significantly increased SIRT1 expression in C2C12 myotubes under low glucose conditions, which was associated with an impaired insulin ability to exert myogenic-stimulating action [28]. However, in our relatively short-term, 6 h experiment, changes in SIRT1 may influence substrate metabolism. Therefore, we can hypothesize that an increased muscle SIRT1 expression during hyperinsulinemia might represent an additional mechanism to maintain muscle glucose uptake.

As in AT, Intralipid/heparin infusion negated the insulin effect on muscle SIRT1 expression. Baseline tissue SIRT1 reflect rather long-term processes regulating its expression whereas the effects of insulin and FFA show short-term regulation of SIRT1 expression. Thus, although our data do not indicate muscle SIRT1 as a modulator of long-term insulin sensitivity, it is possible that it is regulated by short-term insulin fluctuations/nutrient availability to exert some metabolic effects.

The strengths of our study include: use of the “gold standard” in measurement of insulin sensitivity, i.e., the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp; analysis of AT and muscle gene expression in a human study with a large group of participants and the examination of an apparently healthy study population, which allowed us to assess early events in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance, without the confounding effects of hyperglycemia, morbid obesity and other diseases. Also, we for the first time report the relationship between AT SIRT1 and SLC2A4 as well as the tissue-specific effect of hyperinsulinemia on SIRT1 expression.

One limitation of our study arises from the fact that limited tissue availability prevented SIRT1 protein expression being measured in samples from all participants. Nevertheless, we were able to demonstrate an excellent correlation between AT and muscle SIRT1 mRNA and protein expression. We were also able to validate the major findings of our study at the protein level in subgroups of participants, both in AT and in muscle. Another limitation of our study is the fact that one cannot establish cause-effect relationship on the basis of our results.

In conclusion, our data show that AT, but not skeletal muscle, SIRT1 is associated with insulin sensitivity in healthy young humans, possibly because of its correlation with adipose tissue SLC2A4 expression. Insulin differentially regulates AT and skeletal muscle SIRT1 expression in the short-term and circulating FFA elevation negates these effects, which may be associated with lipid-induced insulin resistance.

References

S. Imai, C.M. Armstrong, M. Kaeberlein, L. Guarente, Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase. Nature 403, 795–800 (2000)

S. Mariani, D. Fiore, S. Basciani, A. Persichetti, S. Contini, C. Lubrano, L. Salvatori, A. Lenzi, L. Gnessi, Plasma levels of SIRT1 associate with non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases in obese patients. Endocrine 49, 711–716 (2015)

F. Liang, S. Kume, D. Koya, SIRT1 and insulin resistance. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 5, 367–373 (2009)

S. Fröjdö, C. Durand, L. Molin, A.L. Carey, A. El-Osta, B.A. Kingwell, M.A. Febbraio, F. Solari, H. Vidal, L. Pirola, Phosphoinositide 3-kinase as a novel functional target for the regulation of the insulin signaling pathway by SIRT1. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 335, 166–176 (2011)

C. Sun, F. Zhang, X. Ge, T. Yan, X. Chen, X. Shi, Q. Zhai, SIRT1 improves insulin sensitivity under insulin-resistant conditions by repressing PTP1B. Cell. Metab. 6, 307–319 (2007)

J. Zhang, The direct involvement of SirT1 in insulin-induced insulin receptor substrate-2 tyrosine phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 34356–34364 (2007)

M.P. Gillum, M.E. Kotas, D.M. Erion, R. Kursawe, P. Chatterjee, K.T. Nead, E.S. Muise, J.J. Hsiao, D.W. Frederick, S. Yonemitsu, A.S. Banks, L. Qiang, S. Bhanot, J.M. Olefsky, D.D. Sears, S. Caprio, G.I. Shulman, SirT1 regulates adipose tissue inflammation. Diabetes 60, 3235–3245 (2011)

T. Yoshizaki, J.C. Milne, T. Imamura, S. Schenk, N. Sonoda, J.L. Babendure, J.C. Lu, J.J. Smith, M.R. Jirousek, J.M. Olefsky, SIRT1 exerts anti-inflammatory effects and improves insulin sensitivity in adipocytes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 1363–1374 (2009)

A.S. Banks, N. Kon, C. Knight, M. Matsumoto, R. Gutiérrez-Juárez, L. Rossetti, W. Gu, D. Accilli, SirT1 gain of function increases energy efficiency and prevents diabetes in mice. Cell. Metab. 8, 333–341 (2008)

Z. Gerhart-Hines, J.T. Rodgers, O. Bare, C. Lerin, S.H. Kim, R. Mostoslavsky, F.W. Alt, Z. Wu, P. Puigserver, Metabolic control of muscle mitochondrial function and fatty acid oxidation through SIRT1/PGC-1alpha. Embo. J. 26, 1913–1923 (2007)

S. Schenk, C.E. McCurdy, A. Philp, M.Z. Chen, M.J. Holliday, G.K. Bandyopadhyay, O. Osborn, K. Baar, J.M. Olefsky, Sirt1 enhances skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity in mice during caloric restriction. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 4281–4288 (2011)

J.N. Feige, M. Lagouge, C. Canto, A. Strehle, S.M. Houten, J.C. Milne, P.D. Lambert, C. Mataki, P.J. Elliott, J. Auwerx, Specific SIRT1 activation mimics low energy levels and protects against diet-induced metabolic disorders by enhancing fat oxidation. Cell Metab. 8, 347–358 (2008)

J.C. Milne, P.D. Lambert, S. Schenk, D.P. Carney, J.J. Smith, D.J. Gagne, L. Jin, O. Boss, R.B. Perni, C.B. Vu, J.E. Bemis, R. Xie, J.S. Disch, P.Y. Ng, J.J. Nunes, A.V. Lynch, H. Yang, H. Galonek, K. Israelian, W. Choy, A. Iffland, S. Lavu, O. Medvedik, D.A. Sinclair, J.M. Olefsky, M.R. Jirousek, P.J. Elliott, C.H. Westphal, Small molecule activators of SIRT1 as therapeutics for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Nature 450, 712–716 (2007)

M. Lagouge, C. Argmann, Z. Gerhart-Hines, H. Meziane, C. Lerin, F. Daussin, N. Messadeq, J. Milne, P. Lambert, P. Elliott, B. Geny, M. Laakso, P. Puigserver, J. Auwerx, Resveratrol improves mitochondrial function and protects against metabolic disease by activating SIRT1 and PGC-1alpha. Cell 127, 1109–1122 (2006)

S. Timmers, E. Konings, L. Bilet, R.H. Houtkooper, T. van de Weijer, G.H. Goossens, J. Hoeks, S. van der Krieken, D. Ryu, S. Kersten, E. Moonen-Kornips, M.K.C. Hesselink, I. Kunz, V.B. Schrauwen-Hinderling, E. Blaak, J. Auwerx, P. Schrauwen., Calorie restriction-like effects of 30 days of resveratrol supplementation on energy metabolism and metabolic profile in obese humans. Cell Metab. 14, 612–622 (2011)

L. Bordone, D. Cohen, A. Robinson, M.C. Motta, E. van Veen, A. Czopik, A.D. Steele, H. Crowe, S. Marmor, J. Luo, W. Gu, L. Guarente, SIRT1 transgenic mice show phenotypes resembling calorie restriction. Aging Cell 6, 759–767 (2007)

P.T. Pfluger, D. Herranz, S. Velasco-Miguel, M. Serrano, M.H. Tschop, Sirt1 protects against high-fat diet-induced metabolic damage. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 9793–9798 (2008)

M. Karczewska-Kupczewska, I. Kowalska, A. Nikołajuk, A. Adamska, M. Zielińska, N. Kamińska, E. Otziomek, M. Górska, M. Strączkowski, Circulating brain-derived neurotrophic factor concentration is downregulated by intralipid/heparin infusion or high-fat meal in young healthy male subjects. Diabetes Care 35, 358–362 (2012)

M. Karczewska-Kupczewska, M. Stefanowicz, N. Matulewicz, A. Nikołajuk, M. Strączkowski, Wnt signaling genes in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle of humans with different degrees of insulin sensitivity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 101, 3079–3087 (2016)

E. Rappou, S. Jukarainen, R. Rinnankoski-Tuikka, S. Kaye, S. Heinonen, A. Hakkarainen, J. Lundbom, N. Lundbom, V. Saunavaara, A. Rissanen, K.A. Virtanen, E. Pirinen, K.H. Pietiläinen, Weight loss is associated with increased NAD(+)/SIRT1 expression but reduced PARP activity in white adipose tissue. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 101, 1263–1273 (2016)

S. Jukarainen, S. Heinonen, J.T. Rämö, R. Rinnankoski-Tuikka, E. Rappou, M. Tummers, M. Muniandy, A. Hakkarainen, J. Lundbom, N. Lundbom, J. Kaprio, A. Rissanen, E. Pirinen, K.H. Pietiläinen, Obesity is associated with low NAD(+)/SIRT pathway expression in adipose tissue of BMI-discordant monozygotic twins. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 101, 275–283 (2016)

S.B. Pedersen, J. Ølholm, S.K. Paulsen, M.F. Bennetzen, B. Richelsen, Low Sirt1 expression, which is upregulated by fasting, in human adipose tissue from obese women. Int. J. Obes. 32, 1250–1255 (2008)

Y.S. Song, S.K. Lee, Y.J. Jang, H.S. Park, J.H. Kim, Y.J. Lee, Y.S. Heo, Association between low SIRT1 expression in visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissues and metabolic abnormalities in women with obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 101, 341–348 (2013)

S.J. Clark, M. Falchi, B. Olsson, P. Jacobson, S. Cauchi, B. Balkau, M. Marre, O. Lantieri, J.C. Andersson, M. Jernås, T.J. Aitman, S. Richardson, L. Sjöström, H.Y. Wong, L.M. Carlsson, P. Froguel, A.J. Walley, Association of sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) gene SNPs and transcript expression levels with severe obesity. Obesity 20, 178–185 (2012)

S. Mariani, G. Di Rocco, G. Toietta, M.A. Russo, E. Petrangeli, L. Salvatori, Sirtuins 1-7 expression in human adipose-derived stem cells from subcutaneous and visceral fat depots: influence of obesity and hypoxia. Endocrine 57, 455–463 (2017)

J. Rutanen, N. Yaluri, S. Modi, J. Pihlajamäki, M. Vänttinen, P. Itkonen, S. Kainulainen, H. Yamamoto, M. Lagouge, D.A. Sinclair, P. Elliott, C. Westphal, J. Auwerx, M. Laakso, SIRT1 mRNA expression may be associated with energy expenditure and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes 59, 829–835 (2010)

N. Klöting, M. Fasshauer, A. Dietrich, P. Kovacs, M.R. Schön, M. Kern, M. Stumvoll, M. Bluher, Insulin-sensitive obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 299, E506–E515 (2010)

T. Nedachi, A. Kadotani, M. Ariga, H. Katagiri, M. Kanzaki, Ambient glucose levels qualify the potency of insulin myogenic actions by regulating SIRT1 and FoxO3a in C2C12 myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 294, E668–E678 (2008)

A.T. White, C.E. McCurdy, A. Philp, D.L. Hamilton, C.D. Johnson, S. Schenk, Skeletal muscle-specific overexpression of SIRT1 does not enhance whole-body energy expenditure or insulin sensitivity in young mice. Diabetologia 56, 1629–1637 (2013)

A.E. Brandon, J. Tid-Ang, L.E. Wright, E. Stuart, E. Suryana, N. Bentley, N. Turner, G.J. Cooney, N.B. Ruderman, E.W. Kraegen, Overexpression of SIRT1 in rat skeletal muscle does not alter glucose induced insulin resistance. PLoS ONE 10, e0121959 (2015)

A.T. White, A. Philp, H.N. Fridolfsson, J.M. Schilling, A.N. Murphy, D.L. Hamilton, C.E. McCurdy, H.H. Patel, S. Schenk, High-fat diet-induced impairment of skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity is not prevented by SIRT1 overexpression. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 307, E764–E772 (2014)

E.D. Abel, O. Peroni, J.K. Kim, Y.B. Kim, O. Boss, E. Hadro, T. Minnemann, G.I. Shulman, B.B. Kahn, Adipose-selective targeting of the GLUT4 gene impairs insulin action in muscle and liver. Nature 409, 729–733 (2001)

E. Carvalho, K. Kotani, O.D. Peroni, B.B. Kahn, Adipose-specific overexpression of GLUT4 reverses insulin resistance and diabetes in mice lacking GLUT4 selectively in muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 289, E551–E561 (2005)

C. Hofmann, K. Lorenz, J.R. Colca, Glucose transport deficiency in diabetic animals is corrected by treatment with the oral antihyperglycemic agent pioglitazone. Endocrinology 129, 1915–1925 (1991)

A.R. Moschen, V. Wieser, R.R. Gerner, A. Bichler, B. Enrich, P. Moser, C.F. Ebenbichler, S. Kaser, H. Tilg, Adipose tissue and liver expression of SIRT1, 3, and 6 increase after extensive weight loss in morbid obesity. J. Hepatol. 59, 1315–1322 (2013)

H.Y. Cohen, C. Miller, K.J. Bitterman, N.R. Wall, B. Hekking, B. Kessler, K.T. Howitz, M. Gorospe, R. de Cabo, D.A. Sinclair, Calorie restriction promotes mammalian cell survival by inducing the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science 305, 390–392 (2004)

A. Chalkiadaki, L. Guarente, High-fat diet triggers inflammation-induced cleavage of SIRT1 in adipose tissue to promote metabolic dysfunction. Cell Metab. 16, 180–188 (2012)

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the grant UDA-POIG.01.03.01-00-128/08 from the Program Innovative Economy 2007–2013, partly financed by the European Union within the European Regional Development Fund. Monika Karczewska-Kupczewska was also supported by REFRESH Project (grant number FP7-REGPOT-2010-1-264103).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Stefanowicz, M., Nikołajuk, A., Matulewicz, N. et al. Adipose tissue, but not skeletal muscle, sirtuin 1 expression is decreased in obesity and related to insulin sensitivity. Endocrine 60, 263–271 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-018-1544-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-018-1544-1