Abstract

Improvement in DNA technology is increasingly revealing unexpected/unknown mutations in healthy persons and generating anxiety due to their still unknown health consequences. We report a 44-year-old healthy father of a 10-year-old daughter with bilateral coloboma and hearing loss, but without muscle weakness, in whom a whole-genome CGH revealed a deletion of exons 38–44 in the dystrophin gene. This mutation was inherited from her asymptomatic father, who was further clinically and molecularly evaluated for prognosis and genetic counseling (GC). This deletion was never identified by us in 982 Duchenne/Becker patients. To assess whether the present case represents a rare case of non-penetrance, and aiming to obtain more information for prognosis and GC, we suggested that healthy older relatives submit their DNA for analysis, to which several complied. Mutation analysis revealed that his mother, brother, and 56-year-old maternal uncle also carry the 38–44 deletion, suggesting it an unlikely cause of muscle weakness. Genome sequencing will disclose mutations and variants whose health impact are still unknown, raising important problems in interpreting results, defining prognosis, and discussing GC. We suggest that, in addition to family history, keeping the DNA of older relatives could be very informative, in particular for those interested in having their genome sequenced.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The reduced cost of DNA sequencing has launched several genome population projects in an attempt to clarify the contribution of genetic diversity to normal human as well as disease-related traits. Next-generation DNA sequencing can provide insight into different types of genetic variation that characterize the human genome, such as single-nucleotide polymorphisms, copy-number variation, mobile elements as well as the burden of deleterious variants that may be present in our genome (MacArthur et al. 2012; Quintana-Murci 2012). Several ongoing whole genome–sequencing projects are also focusing on centenarians or older individuals, in particular, to enhance our understanding on genetic versus environment contribution to healthy aging (Altshuler et al. 2010). Additionally, sequencing the genome of healthy older individuals will be extremely important as a database to interpret the significance of novel variants found in younger subjects, some of them associated with well-established Mendelian disorders as reported here.

Duchenne (DMD) and Becker (BMD) muscular dystrophies are X-linked allelic disorders caused by mutations in the dystrophin gene, which may result in the absence (DMD) or a defective (BMD) muscle protein dystrophin (Hoffman et al. 1987; Monaco et al. 1988). In DMD, which affects around 1 in 3,000/4,000 male births, the disease progression is very similar in all affected patients. Without any medical intervention, affected patients are usually confined to a wheelchair around age 10–12, and in the second decade, they are completely dependent for all activities. Death usually occurs as a result of respiratory failure or cardiac impairment in the second decade. Differently from DMD, BMD is characterized by a wide clinical variability. Some patients are confined to a wheelchair before age 20, while others may remain ambulant until late in life. Previous genotype:phenotype correlation studies have shown that the severity of the clinical course depends on the amount of muscle dystrophin and on the site of the mutation (Hoffman et al. 1988; Koenig et al. 1989; Vainzof et al. 1993). Deletions in the rod domain of the dystrophin gene are usually associated with a milder phenotype (Passos-Bueno et al. 1994), while those that involve the N or C-terminal domains cause a more severe course (Hoffman et al. 1988), although prognosis in younger patients can be difficult.

Results

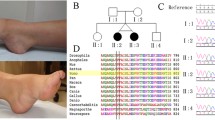

Here, we report an apparently clinically normal man carrying a deletion in the dystrophin gene who was indirectly ascertained through his daughter (IV-2, Fig. 1). This 10-year-old girl was referred for genetic studies due to facial dysmorphism, neurological and behavioral abnormalities, and attention deficit disorder with mild cognitive impairment, but no muscle weakness. Whole-genome array CGH performed elsewhere (Genome Dx Report) revealed her to carry a 179-kb deletion in the dystrophin gene that is apparently unrelated to her condition. This deletion was inherited from her father who was referred to us for further evaluation and genetic counseling.

The father, a 44-year-old healthy male, was clinically and molecularly evaluated in the Human Genome Research Center at the University of São Paulo. All studies were done following written informed consent.

Clinical and neurological examination showed that this father, who was our proband, is completely asymptomatic. He has no visible calf hypertrophy and is able to run and jump. He reportedly plays soccer every weekend and has no signs of fatigue, cramps, or other symptoms.

Pedigree analysis (Fig. 1) revealed that our proband (III-1) has two daughters (IV-1 and IV-2, aged, respectively, 16 and 10 years) and two younger siblings: a brother (III-3, aged 39) and a sister (III-5, aged 43), both clinically normal. His father (II-4, currently 70 years old) had two brothers (II-2 and II-3) and one sister (II-1). One of the paternal uncles (II-3) died of heart attack at age 39, and both the father and older paternal uncle have a heart condition. His mother (II-5), who is currently 64, has three younger siblings: one sister (II-6) who is 61, and two brothers (II-7 and II-9) aged, respectively, 56 and 44 years old. None of them have any clinical condition.

Complementary exams on the father showed that his serum creatine kinase was borderline (223 U/l; normal, up to 189 U/l) (Zatz et al. 1978). DNA analysis through MLPA (multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification) screening for whole dystrophin gene confirmed the presence of an “in frame” deletion spanning exons 38 to 44.

Muscle biopsy revealed histological characteristic of normal muscle (Fig. 2a). Immunofluorescence muscle protein analysis for dystrophin, using antibodies against the N-terminal and C-terminal regions of the protein, showed a normal and continuous sarcolemmal pattern of distribution (Fig. 2a). Sarcoglycans proteins were also normally distributed (Fig. 2a). Through Western blot analysis, a strong dystrophin band of ~390 kDa was observed with antibodies against the rod domain (DYS1) and C-terminal domain (DYS2), compatible with the size expected for the transcript of a gene with the partial deletion of exons 38–44. Calpain-3 and dysferlin bands were normal (Fig. 2b).

Histological (HE) and immunohistochemical analysis of the proband’s muscle biopsy, showing in a—normal muscle histology in HE staining, and normal dystrophin (antibodies against the N-terminal and C-terminal domains) and sarcoglycan (α-SG) distribution in muscle sarcolemma. In b—Western blot analysis for dystrophin showing a dystrophin band of ~390 kDa, in normal quantity, using antibodies against the rod domain (DYS1) and C-terminal domain (DYS2). In the triple reaction, calpain-3 and dysferlin bands are normal

Discussion

Improvement in DNA technology is increasingly identifying unexpected mutations in healthy persons, causing anxiety particularly when no information is available about their possible health consequences. “In frame” deletions of variable extent, mostly in the rod domain of the dystrophin gene, have been reported before in individuals with no or with very mild symptoms, such as elevated serum CK or myalgia (Ferreiro et al. 2009; Gospe et al. 1989; Ishigaki et al. 1996; Melis et al. 1998).

Two separate mutation prediction databases have classified the molecular defect found in our proband as compatible with Becker muscular dystrophy (The UMD-DMD France mutation database) or of unknown consequence (http://www.umd.be/DMD/4DACTION/Web_Large_rearrangement/c.5326_6438de). On the other hand, a duplication involving the same exons was reported in a Chinese patient with a DMD phenotype (http://www.dmd.nl/#eupdate, and Yuge et al. 1999). This mutation has never been found among 1,600 DMD/BMD patients analyzed in our center, 982 of them through MLPA technology (unpublished data). Therefore, it was difficult to conclude whether the lack of symptoms of our proband represents an exception or whether he could be reassured about his prognosis. In addition to his own future, this information was also important for genetic counseling of his daughters since it is expected that both carry the 38–44 deletion and thus have a chance of 50 % of transmitting this mutation to their male offspring.

In the present case, we did not know whether the 38–44 dystrophin deletion was a de novo mutation in the father or was already segregating in the family. This possibility was discussed during genetic counseling, and it was explained that DNA analysis of older family members could be informative in addressing this question. Although at first our proband was reluctant at the possibility of causing anxiety in other healthy relatives, he decided to contact them and several key members agreed to have their DNA screened for mutations in the dystrophin gene.

MLPA analysis in 4 additional relatives (III-3, II-5, II-7, and II-9) revealed that three of them carry the same 38–44 deletion: his mother (II-5), his younger brother (III-3), and his maternal uncle (II-7). Both grandparents are deceased, and therefore, we could not investigate further the origin of this mutation, but according to our proband′s information, they had no muscle weakness. It is not possible to rule out that our proband will have some muscle pathology later in life or that the same mutation could be pathogenic in an individual with a different genetic background. However, the finding of the same mutation in his asymptomatic brother and uncle who is currently 56 and also completely asymptomatic suggests that this mutation is unlikely to result in muscle weakness, at least in the present family.

Advances in genome-sequencing analysis will uncover genetic mutations and variants whose impacts in health are still unknown. This will raise important problems in interpreting results and defining prognosis as well as in genetic counseling of at-risk family members. Indeed, the recent analysis of 185 genomes has shown that all humans carry many genetic variants predicted to cause loss of function of protein-coding genes and approximately 20 genes are completely inactivated (MacArthur et al. 2012).

The finding of unexpected and novel mutations will probably be ever more frequent and their impact will have to be analyzed carefully during genetic counseling. Many disease-causing mutations reported in the literature have later been shown to be benign polymorphisms or only partially penetrant (Altshuler et al. 2010). Other publications on individual genome sequences have also found homozygosity for alleged severe disease mutations despite no evidence for the associated phenotype in the sequenced individual (Lupski et al. 2010). In short, the available mutation databases are quite imperfect guides to assess sequence variant pathogenicity. On this respect, deep genome analysis of healthy octogenarians (currently underway in our center), the whole-genome sequencing of 1,000 healthy older individuals (the Scripps Wellderly Study), and of 100 centenarians may bring valuable information, in particular for adult onset disorders.

In the family presented here, the observation that the same mutation was present in older healthy relatives was very helpful and reassuring, in particular because the penetrance of a specific mutation can vary on different genetic backgrounds. Therefore, in addition to population studies, we suggest keeping the DNA of your older family members. It could be very informative, in particular for those who want to have their own genome sequenced.

References

Altshuler, D., Durbin, R. M., Abecasis, G. R., Bentley, D. R., Chakravarti, A., Clark, A. G., et al., The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium (2010) A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature, 467(7319), 1061–1073.

Ferreiro, V., Giliberto, F., Muñiz, G. M., Francipane, L., Marzese, D. M., Mampel, A., et al. (2009). Asymptomatic Becker muscular dystrophy in a family with a multiexon deletion. Muscle and Nerve, 39(2), 239–243.

Gospe, S. M., Jr, Lazaro, R. P., Lava, N. S., Grootscholten, P. M., Scott, M. O., & Fischbeck, K. H. (1989). Familial X-linked myalgia and cramps: a nonprogressive myopathy associated with a deletion in the dystrophin gene. Neurology, 39(10), 1277–1280.

Hoffman, E. P., Brown, R. H., Jr, & Kunkel, L. M. (1987). The protein product of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy locus. Cell, 51, 919–928.

Hoffman, E. P., Fischbeck, K. H., Brown, R. H., Johnson, M., Medori, R., Loike, J. D., et al. (1988). Characterization of dystrophin in muscle-biopsy specimens from patients with Duchenne’s or Becker’s muscular dystrophy. The New England Journal of Medicine, 318(21), 1363–1368.

Ishigaki, C., Patria, S. Y., Nishio, H., Yabe, M., & Matsuo, M. (1996). A Japanese boy with myalgia and cramps has a novel in-frame deletion of the dystrophin gene. Neurology, 46(5), 1347–1350.

Koenig, M., Beggs, A. H., Moyer, M., Scherpf, S., Heindrich, K., Bettecken, T., et al. (1989). The molecular basis for Duchenne versus Becker muscular dystrophy: Correlation of severity with type of deletion. American Journal of Human Genetics, 45(4), 498–506.

Lupski, J. R., Reid, J. G., Gonzaga-Jauregui, C., Rio Deiros, D., Chen, D. C., Nazareth, L., et al. (2010). Whole-genome sequencing in a patient with Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy. The New England Journal of Medicine, 362(13), 1181–1191.

MacArthur, D. G., Balasubramanian, S., Frankish, A., Huang, N., Morris, J., Walter, K., et al. (2012). A systematic survey of loss-of-function variants in human protein-coding genes. Science, 335(6070), 823–828.

Melis, M. A., Cau, M., Muntoni, F., Mateddu, A., Galanello, R., Boccone, L., et al. (1998). Elevation of serum creatine kinase as the only manifestation of an intragenic deletion of the dystrophin gene in three unrelated families. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology, 2(5), 255–261.

Monaco, A. P., Bertelson, C. J., Liechti-Gallati, S., Moser, H., & Kunkel, L. M. (1988). An explanation for phenotypic differences between patients bearing partial deletions of DMD locus. Genomics, 2(1), 90–95.

Passos-Bueno, M. R., Vainzof, M., Marie, S. K., & Zatz, M. (1994). Half the dystrophin gene is apparently enough for a mild clinical course: Confirmation of its potential use for gene therapy. Human Molecular Genetics, 3(6), 919–922.

Quintana-Murci, L. (2012). Gene losses in the human genome. Science, 335, 806–807.

Vainzof, M., Takata, R. I., Passos-Bueno, M. R., Pavanello, R. C., & Zatz, M. (1993). Is the maintenance of the C-terminus domain of dystrophin enough to ensure a milder Becker muscular dystrophy phenotype? Human Molecular Genetics, 2(1), 39–42.

Yuge, L., Hui, L., & Bingdi, X. (1999). Detection of gene deletions in Chinese patients with Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy using CDNA probes and the polymerase chain reaction method. Life Sciences, 65(9), 863–869.

Zatz, M., Shapiro, L. J., Campion, D. S., Oda, E., & Kaback, M. M. (1978). Serum pyruvate-kinase (PK) and creatine-phosphokinase (CPK) in progressive muscular dystrophies. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 36(3), 349–362.

Acknowledgments

The collaboration of the following persons is gratefully acknowledged: Constancia Urbani, Marta Canovas, Leticia Nogueira, Dr. Lydia U. Yamamoto, Fernando Luis Molina, Dr. Alessandra Splendore, Dr. Maria Rita Passos-Bueno. Special thanks to Daniel MacArthur for valuable suggestions. This work was supported with grants of CEPID-FAPESP (Centro de Pesquisa, Inovação e Difusão-Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo), CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico), INCT (Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia), FINEP and ABDIM.

Conflict of interest

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Zatz, M., Pavanello, R.C.M., Lourenço, N.C.V. et al. Assessing Pathogenicity for Novel Mutation/Sequence Variants: The Value of Healthy Older Individuals. Neuromol Med 14, 281–284 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12017-012-8186-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12017-012-8186-x