Abstract

Non-hereditary angioedema (AE) with normal C1 esterase inhibitor (C1INH) can be presumably bradykinin- or mast cell-mediated, or of unknown cause. In this systematic review, we searched PubMed, EMBASE, and Scopus to provide an overview of the efficacy of different treatment options for the abovementioned subtypes of refractory non-hereditary AE with or without wheals and with normal C1INH. After study selection and risk of bias assessment, 61 articles were included for data extraction and analysis. Therapies were described for angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced AE (ACEi-AE), for idiopathic AE, and for AE with wheals. Described treatments consisted of ecallantide, icatibant, C1INH, fresh frozen plasma (FFP), tranexamic acid (TA), and omalizumab. Additionally, individual studies for anti-vitamin K, progestin, and methotrexate were found. Safety information was available in 26 articles. Most therapies were used off-label and in few patients. There is a need for additional studies with a high level of evidence. In conclusion, in acute attacks of ACEi-AE and idiopathic AE, treatment with icatibant, C1INH, TA, and FFP often leads to symptom relief within 2 h, with limited side effects. For prophylactic treatment of idiopathic AE and AE with wheals, omalizumab, TA, and C1INH were effective and safe in the majority of patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

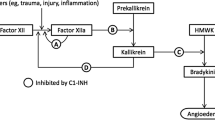

Angioedema (AE) frequently occurs as part of urticaria, a disease characterized by the development of wheals, AE, or both [1, 2]. AE with wheals, also known as chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU), is presumably mast cell-mediated [1–3]. AE without significant wheals can be the presenting symptom of a variety of diagnoses, such as hereditary AE caused by C1 esterase inhibitor (C1INH) deficiency, resulting in the release of the key mediator bradykinin [2]. Accumulation of bradykinin can also be caused by the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi-AE) in patients with normal C1INH [2, 4]. ACEi-AE is estimated to occur in up to 0.68 % of patients who receive ACE inhibitors [5]. However, a majority of patients suffer idiopathic acquired AE, which implies AE with normal C1INH with no family history of AE, in which known causes of AE have been excluded [2, 3]. It is unclear to what extent idiopathic AE is similar to angioedema with wheals (CSU) [3], or to presumably bradykinin-mediated subtypes of AE.

Second-generation antihistamines are used as prophylactic treatment of AE with wheals and idiopathic AE [1, 2]. Antihistamines and corticosteroids, and, in life-threatening cases, adrenaline, represent the standard emergency room treatment of acute attacks of AE [2, 4, 6, 7]. CSU is thought to affect 0.5–1 % of the global population at any given time, with an estimated 67 % of patients with CSU shown to have both hives and AE and 1–13 % to have AE alone [8, 9]. In AE with wheals, daily treatment with antihistamines does not always lead to a complete absence of symptoms [1], and it is estimated that every third or fourth patient remains symptomatic even despite high-dose antihistamine treatment [8, 9]. Omalizumab is effective in patients with CSU [1, 10–15], although it has not been studied extensively in AE without wheals. Patients with ACEi-AE generally do not respond to conventional therapy [5, 6]. Pathophysiology suggests that drugs registered for hereditary angioedema (HAE) due to C1INH deficiency could also be effective in ACEi-AE. Several drugs are currently available, including (1) antifibrinolytic agents such as tranexamic acid (TA); (2) attenuated androgens such as danazol; (3) replacement of deficient proteins using fresh frozen plasma (FFP); (4) C1INH concentrates, which inhibit the formation of bradykinin; (5) the selective plasma kallikrein inhibitor ecallantide; and (6) the selective bradykinin B2 receptor antagonist icatibant [2]. Some of these drugs are licensed to treat acute attacks, whereas others are used for prophylactic treatment [2]. The efficacy of these drugs in refractory AE with normal C1INH has not been fully elucidated.

This systematic literature review aims to provide an overview of therapeutic options and their efficacy in patients with AE with normal C1INH, but refractory to conventional therapy. We have distinguished between treatment of acute attacks vs. prophylactic treatment and included bradykinin-mediated and mast cell-mediated non-hereditary AE as well as idiopathic AE.

Methods

This systematic literature review was conducted using the criteria mentioned in the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [16].

Search Strategies

Secondary evidence databases National Guideline Clearinghouse, CBO guidelines, Trip Database, and the Cochrane Library were searched for guidelines up to 20th April 2015 using several synonyms for the domain, angioedema, and determinant, treatment options (Table 1). Subsequently, primary evidence electronic databases PubMed, EMBASE, and Scopus were searched for articles up to 20th April 2015 using the domain and determinants as previously described. Synonyms for outcome measurements were not included in the search strategy so as to maximize the yield of articles and to allow for different outcome measures, including but not limited to time to initial or complete response and decrease in attack frequency or severity. The search was limited by title or abstract and, in Scopus, by title, abstract, or keywords.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Articles were included when the described study populations suffered ACEi-AE, AE with wheals (CSU), or idiopathic AE with normal C1INH. Furthermore, only articles describing pharmacological treatment of AE were included. This included both observational studies (case report and case series) and intervention trials (cohort studies or randomized controlled trials, RCTs). Any pharmacological treatment other than antihistamines up to fourfold, prednisolone, or adrenaline could be included. Articles were considered appropriate to be included only when sufficient details regarding type of treatment, dose, interval between doses, time to initial response, and time to maximum or complete response were described. Articles describing only ineffective therapies were described separately. For full understanding of scientific content by the authors who performed the selection of studies, only articles written in English, Dutch, or German were included. Recent articles for which only the title and abstract were available, such as congress abstracts, were included only if sufficient information about the patient(s), treatment regimen, and response were described. For icatibant only, when dose was missing, it was assumed that 30 mg was used due to the packaging of this product. Therefore, these articles could be included, although the dose was shown as “not reported” in the results. Articles regarding AE with wheals could only be included when treatment results specifically for AE symptoms could be extracted rather than only for the symptoms wheals and itch. Outcome measurements could differ for articles regarding an acute attack or prophylactic treatment: in acute settings, initial and complete responses refer to the resolution of a single attack of swelling, whereas in prophylactic or chronic settings this refers to a decrease in attack frequency or severity.

Studies were excluded when AE was caused by hereditary or acquired complement C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) deficiency, coagulation factor 12 (fXII) mutation, formerly known as HAE type 3, or other known causes of AE, including allergy, or when AE was an adverse effect of any therapy other than ACEi.

Selection of Studies

Unique titles and abstracts and subsequently full texts were screened for eligibility. Articles published in or after 2013 were screened by at least two independent reviewers (ME, MG, and MB), results were compared, and disagreements were discussed and resolved. Articles published before 2013 were screened by one reviewer (ME), and for assessment of unclear articles only, a second reviewer (MB) was available.

Risk of Bias

Risk of bias (RoB) for each study was assessed by one reviewer (MG) and verified by a second reviewer (ME). To allow for a careful assessment of observational studies as well as intervention studies, criteria for risk of bias assessment from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [17] were supplemented with items from the CARE guidelines checklist [18]. The risk of selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, and selective reporting bias was assessed. A low risk of bias was preferred and therefore displayed as a positive finding (+), whereas a high risk of bias was undesirable and displayed as a negative finding (−). The risk of selection bias was considered low (+) for observational studies when symptoms and important clinical findings were described. The risk of performance bias was considered low (+) when the chosen treatment option and dose regimen were both recorded. The risk of detection bias was assessed with regard to (1) effect of treatment and (2) adverse events and was considered low if this was noted in the article. In case of multiple patient groups including more than one type of AE, the risk of detection bias was considered low only when results could be extracted for the subgroups separately and unclear (+/−) when results were described for the total group. The risk of attrition bias was low (+) when reasons for exclusion or dropout were reported, and for controlled studies, the dropouts were balanced between treatment and placebo groups. The risk for reporting bias was low (+) when all prespecified outcomes were fully addressed in the results. Authors of RCTs were contacted to retrieve missing trial details. All evaluations were compared and disagreements between authors were discussed and resolved.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

For each study, data extraction was performed by one reviewer and verified by a second reviewer (ME and MG). Data regarding the study design, therapy, previous therapies, and effect of the described therapy were recorded in tables. For treatment of acute attacks and prophylactic treatment of AE, available efficacy results were described per subtype and per treatment option. Definitions for response were adopted from the original articles. Articles describing ineffective treatment options were described separately. If information about adverse effects was available, this was collected additionally for each type of treatment. A distinction between serious adverse effects (SAEs) and less severe treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) was made. Additionally, only adverse events possibly, probably, or definitely related to treatment were reported. Adverse effects reported by placebo-treated patients were not taken into account. Due to the high amount of available case reports and low amount of controlled studies, and since outcome measures varied among the study studies, a meta-analysis could not be performed. Instead, results are described using narrative summary technique.

Results

Search Results and Quality Assessment

The search in secondary evidence databases yielded no available aggregated evidence. The search in PubMed, EMBASE, and Scopus yielded 5107 original articles (Fig. 1). After screening titles and abstracts, 4952 articles were excluded. Subsequently, 155 full texts were screened for eligibility, leading to the exclusion of 94 further articles, including 53 articles with a lack of usable information, the use of conservative treatment in 40 articles, and overlap in study population in one article. The remaining 61 articles included 53 full articles and eight (congress) abstracts. Of the 61 included articles, 38 described treatment of AE in acute settings, including 3 RCTs, 2 cohort studies, 4 case series, and 29 case reports. Additionally, 26 of the 61 articles described prophylactic settings, including 1 RCT, 5 cohort studies, 9 case series, and 11 case reports. Three articles described both acute and prophylactic treatment.

All 61 articles underwent RoB assessment (Tables 2 and 3). All of the four included RCTs had a low risk of bias. Of the 57 descriptive studies, 46 had a low risk of bias and 11 had an unclear risk of at least one type of bias. Only 26 addressed safety results with regard to efficacy outcomes.

Treatment of Acute Attacks of AE

With regard to acute attacks of AE refractory to conventional treatment including antihistamines, corticosteroids, and adrenaline, the included articles described treatment of two subtypes: ACEi-AE and idiopathic AE.

ACEi-AE was addressed in 24 articles describing treatment of acute attacks in 154 patients, with study sizes varying from 1 to 58 patients. Outcome measures were (1) time to response (Fig. 2a and Table 4) and/or (2) proportion of patients with response (Fig. 2b and Table 4). As shown in Fig. 2a, described treatment strategies consisted of icatibant (42 patients in ten articles including one RCT) [5, 6, 21, 24, 26, 27, 31, 33, 36, 37], C1INH (14 patients in five articles) [22, 25, 28, 38, 39], FFP (13 patients in six articles) [23, 29, 30, 32, 35, 40], and kanokad (concentrate of vitamin K-dependent coagulation factor anti-vitamin K antagonist in one patient using anti-vitamin K medication concomitantly) [34]. In the 21 included studies for icatibant, C1INH, and FFP, the (median) time to initial response ranged from a few minutes up to 150 min, with one outlier up to 48 h [38]. Time to complete response ranged from 0.5 to 48 h. As shown in Fig. 2b, ecallantide was described additionally in 84 patients in two RCTs [4, 7]. Results for ecallantide were not significant: one RCT identified a difference in response rate vs. placebo of 16 % (95 % confidence interval, −11 to 41 %) [4], and a second RCT revealed a difference in response rate vs. placebo of 10 % (95 % confidence interval, −14 to 34 %) [7]. The level of evidence for C1INH, FFP, and icatibant was low, compared to ecallantide, due to lack of controlled studies. In conclusion, in treatment of acute attacks of ACEi-AE, no significant differences in the response rate between ecallantide and placebo were shown, and icatibant, C1INH, and FFP had similar times to response, mostly less than 2 h.

a–d Responses to treatment. NA not available, Anti-vit K anti-vitamin K, C1INH complement 1 esterase inhibitor, MTX methotrexate, TA tranexamic acid, P progestin. Numbers on the Y-axis represent the reference number for each study; n indicates the number of patients included from each study. Not shown in (c): Mansi et al., 13 of 24 patients had partial response to tranexamic acid. Not shown in (d): Zazzali et al., in 208 patients treated with omalizumab, the mean proportion of AE-free days was 90.1–95.8 % vs. 88.7 % for placebo

Idiopathic AE was addressed in 12 articles describing treatment of acute attacks in 84 patients. Effect of treatment was described as time to response (Fig. 2c and Table 5) or proportion of patients with response (Table 5). Treatment strategies consisted of icatibant (56 patients in nine studies) [19, 20, 41, 44, 46–50], TA (24 patients in one study) [19], C1INH (three patients in three articles) [19, 43, 45], and ecallantide (one patient) [42]. As shown in Fig. 2c, the time to initial response for C1INH ranged from 20 to 120 min and for icatibant from 20 to 45 min, and (median) time to complete response for ecallantide was 1 h. For C1INH, (median) time to complete response was also 1 h, and for icatibant this ranged from 45 min up to 26 h. In addition to Fig. 2c, one study reported response to TA in 13 of 24 patients (54 %) [19]. In conclusion, in acute attacks of idiopathic AE, C1INH, icatibant, and ecallantide had times to response often within 2 h, and TA was effective in more than 50 % of patients.

Prophylactic Treatment of AE

With regard to recurrent AE refractory to conventional treatment, included articles about prophylactic treatment described two subtypes: AE with wheals and idiopathic AE.

AE with wheals was addressed in 11 articles describing 230 patients. Effect was shown as time to response (Fig. 2d and Table 6) [53, 54, 62–64, 66–71]. All articles described treatment with omalizumab after unsuccessful treatment with antihistamines and often additional ineffective treatment options. One manuscript detailed two RCTs for which the results regarding urticaria had been published previously [10, 14]. However, in the included manuscript, specific results with regard to AE were described [53]. In the other articles, which consisted of cohort studies and case series or case reports, the time to initial effect ranged from 1 day to 60 days after administration, and 10 of 22 patients achieved complete remission within a time range varying from 1 day to <150 days [54, 62–64, 66–71]. In conclusion, in prophylactic treatment of AE with wheals, omalizumab had a broad range of time to response and was effective in almost half of the patients.

Lastly, prophylactic treatment of idiopathic AE was addressed in 16 articles describing 168 patients [19, 43, 48, 54–61, 64, 65, 72–74]. Efficacy was shown as proportion of patients with response (Fig. 2e and Table 7) or time to response (Fig. 2f and Table 7). As shown in Fig. 2e, described treatment options were TA (126 patients in six studies) [19, 48, 55, 56, 58, 59], progestin (20 patients in one study) [57], and C1INH (two patients in two studies) [43, 74]. When combining studies, TA led to improvement of symptoms in 92 patients (73 %) and a complete absence of symptoms in another 20 patients (16 %; Table 7). Progestin provided improvement in 19 of 20 patients and C1INH in two of two patients. Figure 2f shows the results for omalizumab (19 patients in six articles) [54, 60, 61, 64, 72, 73] and methotrexate (MTX, one patient) [65]. For omalizumab, in 12 patients (63 %), no further attacks occurred after starting treatment, and the time to initial response ranged from 1 day to 120 days. MTX provided improvement in one patient after 28 days of treatment. In conclusion, in prophylactic treatment of idiopathic AE, TA, omalizumab, and C1INH, as well as progestin and MTX, were effective in a majority of patients.

Ineffective Treatment Options

Ineffective treatment options were described in 21 patients in 12 articles (Table 8) [25, 31, 37, 38, 43, 48, 49, 51, 52, 60, 62, 75]. Nine of them overlap with the previously described articles since they had additionally described a successful treatment option for at least one of the subtypes of AE [25, 31, 37, 38, 43, 48, 49, 60, 62]. In three articles, only ineffective treatment options were described [51, 52, 75]. In total, ineffectiveness was recorded for TA (12 patients), C1INH and FFP (five patients each), and icatibant, MTX, and omalizumab (two patients each). In four patients, more than one therapy was recorded ineffective, in addition to conservative treatment with antihistamines, corticosteroids, and/or adrenaline. In conclusion, ineffectiveness was reported for several therapeutic options commonly used in bradykinin-mediated and mast cell-mediated AE and was reported for individual cases only, resulting in low numbers for each drug.

Safety

The presence or absence of adverse effects was addressed in 25 of the 61 included articles [4–7, 19, 21, 22, 27, 42, 46, 54–60, 62–66, 70, 72, 73] (Table 9). The other 36 articles did not report information on this topic. Thus, safety information was available for 315 patients treated with either ecallantide (87 patients), icatibant (37 patients), TA (125 patients), omalizumab (34 patients), progestin (20 patients), C1INH (ten patients), or MTX (two patients).

A distinction between SAEs and less severe TEAEs was adopted from the included articles, if available. Additionally, only adverse events possibly, probably, or definitely related to treatment are shown in this review. SAEs were reported in six patients, including five AE episodes during treatment with ecallantide (6 % of those treated with ecallantide) and one myocardial infarction during treatment with TA (0.8 %). TEAEs were reported in 13 patients treated with ecallantide (15 %) and 12 treated with icatibant (32 %; all local and related to the administration method). At least 19 patients treated with TA (15 %) reported TEAE, and at least nine treated with omalizumab (26 %). However, TEAEs were presented in the total study populations including also HAE and CSU patients; therefore, the number of patients experiencing adverse effects may be higher. For progestin and MTX, TEAEs were addressed in one article each, where TEAEs were also presented in the total study population including also HAE and CSU patients. For C1INH, no TEAE was reported. In addition, one article described the use of omalizumab during two pregnancies, with no developmental abnormalities in both children [66]. In conclusion, SAEs were reported in 2 % and TEAE in 17 % of patients.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we found several treatment options for patients with refractory AE. For acute attacks of AE, several articles described treatment with icatibant, C1INH, TA, FFP, and ecallantide. For prophylactic treatment of AE, omalizumab, TA, and C1INH were shown effective, and, with fewer included articles, also progestin and MTX. The described treatments showed good efficacy in addition to a favorable safety profile with a low number of mostly mild and self-limiting adverse effects. A limitation of the available literature was the low level of evidence for all treatment options, except ecallantide and icatibant.

In ACEi-AE, high-quality studies were performed for ecallantide, but the response rates compared to placebo were not significant. Many patients responded quickly after treatment with icatibant, C1INH, and TA, but most of the included studies were not controlled and therefore of lower quality in terms of scientific reliability. FFP has shown similar results, but since FFP also contains other substrates including prekallikrein and high-molecular-weight kininogen, it has been hypothesized to have the potential to worsen an acute attack of AE since new bradykinin can be formed [76]. Treatment of refractory ACEi-AE mostly consisted of drugs known for treatment of HAE. The rationale for this is that ACEi-AE is presumably bradykinin-mediated [2]. Icatibant had a similar time to response in ACEi-AE, as previously shown in HAE patients [77]. Ecallantide had stronger beneficial results in HAE patients [78] compared to ACEi-AE patients, partially due to a high response rate in the placebo group. Additional RCTs in HAE patients revealed time to onset of relief within 2 h for pasteurized C1INH, nanofiltered C1INH, and recombinant human C1INH (rhC1INH) [79–81]. In many of the cases included in this review, the onset of relief after C1INH was reported within 1 h of administration, and efficacy results may therefore be quite consistent with the results of C1INH treatment in acute HAE attacks. Very recently, the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health performed a non-systematic literature search and provided a summary of four available guidelines for urticaria and AE, which supports that icatibant, C1INH, ecallantide, and FFP may be useful in the treatment of ACEi-AE [82]. In addition to the results of these therapies in ACEi-AE, we show in the current review that these therapies, with icatibant as the most often studied, may also be effective in the treatment of acute attacks of idiopathic AE. In conclusion, in patients suffering ACEi-AE or an acute attack of idiopathic AE, ecallantide seems to have an effect in a limited number of patients, if any, whereas icatibant, C1INH, TA, and FFP often lead to symptom relief within 2 h, in addition to a good safety profile.

For AE with wheals, also known as CSU, omalizumab was the only treatment option described when conservative treatment had failed. A high success rate, good safety profile, and rapid responses were described, as was shown extensively in patients suffering CSU, which by definition includes AE with wheals [1, 10–15]. In patients suffering idiopathic AE, we show that both licensed HAE drugs and omalizumab seem to have a beneficial effect in a substantial amount of patients, even in those who are very refractory and have had many other treatments prior to the described treatment. When comparing with ACEi-AE, it appears that idiopathic AE responds even more rapidly upon treatment with icatibant, C1INH, or ecallantide. This suggests a role for both bradykinin and mast cells (histamine) in idiopathic AE with normal C1INH, although this was not the objective of the current review. Additionally, in one patient treated with C1INH and two treated with FFP, the time to response of an acute attack was reported to be 2 days [38]. In such cases, one should be aware of the natural course of an attack [1–3, 83]. Furthermore, also for this subtype, the level of evidence is low, and controlled studies remain to be performed. In conclusion, omalizumab, TA, and C1INH were effective and safe in a majority of patients in need of prophylactic treatment of refractory idiopathic AE or AE with wheals.

One needs to keep in mind that all treatment options described are currently off-label in these patient groups worldwide, except for omalizumab in AE with wheals (CSU), and that the findings should be confirmed in clinical trials. Due to the fact that most therapies described have only been registered for other indications recently, the efficacy and safety for the current subtypes of non-HAE have not been studied yet. It remains unclear which (groups of) patients derive a beneficial effect from each type of treatment. For C1INH, a beneficial effect was described even in patients who failed to respond to icatibant and/or FFP. On the contrary, in ACEi-AE and idiopathic AE, patients failed to respond to C1INH, but did respond to icatibant or TA. Similar results were seen for TA, FFP, icatibant, MTX, and omalizumab, indicating the presence of non-responders for each type of treatment in almost each subtype of AE and also indicating that switching treatment options can lead to satisfactory results in some individuals even when both target a similar pathophysiological mechanism.

We opted for a broad overview of the level of evidence of treatment options when performing this systematic review. This was deemed appropriate with regard to the research question and the therapeutic problems physicians face in daily practice. The results may be an overestimation since case reports generally represent one or few patients with positive effects of treatment, and only few cases without response are available possibly due to underreporting. Due to the use of different outcome measures, such as percentage of patients with response or the time to response, it was difficult to compare the results of the studies. Additionally, we found there to be a low level of prior research evidence. Fortunately, in the last couple of years, more extensive research has been published, allowing for the inclusion of several RCTs in this review. Still, our results illustrate the need for further research in these patient groups, including prospective cohort studies and controlled studies. The lack of available guidelines underlines this further. Not included in this review but worthy of mention is the fact that it is known that AE is known to have a detrimental effect on quality of life (QoL) [84]. While the impact on the QoL was not a part of this review, it is striking that this aspect was not addressed in many of the included studies. Disease-specific questionnaires have been developed for AE patients, both with regard to disease activity and QoL [1, 84–86], and we consider QoL an important additional outcome measure both in acute attacks and prophylactic setting studies.

A minority of articles included information with respect to adverse effects of treatment. When reported, only a few patients experienced adverse effects. These were generally mild and self-limiting, and most were known side effects [15, 76, 87–91]. New TEAEs were oropharyngeal discomfort (reported for TA), weight loss (omalizumab), and hypoesthesia, hematuria, muscle spasms, oral candidiasis, and pain in extremity (ecallantide; TEAEs may be unrelated). Notably, for icatibant, only injection-related TEAEs occurred.

In conclusion, for patients suffering angioedema refractory to conservative treatment, several additional treatment options are available with rapid time to response, high response rates, and limited side effects. However, these therapies are off-label, and there is a need for additional studies to provide a high level of scientific evidence. Treatment options differ per subtype of AE. Most promising treatments for acute attacks (ACEi-AE and idiopathic AE) consist of icatibant, C1INH, and FFP, with response often within 2 h and with limited side effects. For prophylactic treatment (idiopathic AE and AE with wheals), the most promising options are omalizumab, TA, and C1INH, with efficacy in a majority of patients, together with limited side effects.

Abbreviations

- ACEi-AE:

-

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema

- AE:

-

Angioedema

- C1INH:

-

C1 esterase inhibitor

- CSU:

-

Chronic spontaneous urticaria

- FFP:

-

Fresh frozen plasma

- fXII:

-

Coagulation factor 12

- HAE:

-

Hereditary angioedema

- RoB:

-

Risk of bias

- MTX:

-

Methotrexate

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- SAE:

-

Serious adverse event

- TA:

-

Tranexamic acid

- TEAE:

-

Treatment-emergent adverse event

References

Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Asero R, Bindslev-Jensen C, Brzoza Z, Canonica GW et al (2014) The EAACI/GA(2) LEN/EDF/WAO Guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria: the 2013 revision and update. Allergy 69:868–887

Cicardi M, Aberer W, Banerji A, Baş M, Bernstein JA, Bork K et al (2014) Classification, diagnosis, and approach to treatment for angioedema: consensus report from the Hereditary Angioedema International Working Group. Allergy 69:602–616

Schulkes KJG, Van den Elzen MT, Hack EC, Otten HG, FM B-KCa, Knulst AC (2015) Clinical similarities among bradykinin-mediated and mast cell-mediated subtypes of non-hereditary angioedema: a retrospective study. Clin Transl Allergy 5:5, eCollection

Lewis LM, Graffeo C, Crosley P, Klausner HA, Clark CL, Frank A et al (2014) Ecallantide for the acute treatment of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med 65:1–10

Baş M, Greve J, Stelter K, Havel M, Strassen U, Rotter N et al (2015) A randomized trial of icatibant in ACE-inhibitor-induced angioedema. N Engl J Med 372:418–425

Baş M, Greve J, Stelter K, Bier H, Stark T, Hoffmann TK et al (2010) Therapeutic efficacy of icatibant in angioedema induced by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a case series. Ann Emerg Med 56:278–282

Bernstein JA, Moellman JJ, Collins SP, Hart KW, Lindsell CJ (2015) Effectiveness of ecallantide in treating angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema in the emergency department. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 114:245–249

Weller K, Maurer M, Grattan C, Nakonechna A, Abuzakouk M, Bérard F et al (2015) ASSURE-CSU: a real-world study of burden of disease in patients with symptomatic chronic spontaneous urticaria. Clin Transl Allergy 5:29

Maurer M, Weller K, Bindslev-Jensen C, Giménez-Arnau A, Bousquet PJ, Bousquet J et al (2011) Unmet clinical needs in chronic spontaneous urticaria. A GA2LEN Task Force report. Allergy Eur J Allergy Clin Immunol 66:317–330

Maurer M, Rosén K, Hsieh H-J, Saini S, Grattan C, Gimenéz-Arnau A et al (2013) Omalizumab for the treatment of chronic idiopathic or spontaneous urticaria. N Engl J Med 368:924–935

Maurer M, Altrichter S, Bieber T, Biedermann T, Bräutigam M, Seyfried S et al (2011) Efficacy and safety of omalizumab in patients with chronic urticaria who exhibit IgE against thyroperoxidase. J Allergy Clin Immunol 128:202–209.e5

Saini S, Rosen KE, Hsieh H-J, Wong DA, Conner E, Kaplan A et al (2011) A randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study of single-dose omalizumab in patients with H1-antihistamine-refractory chronic idiopathic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol 128:567–573.e1

Kaplan A, Ledford D, Ashby M, Canvin J, Zazzali JL, Conner E et al (2013) Omalizumab in patients with symptomatic chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria despite standard combination therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 132:101–109

Saini SS, Bindslev-Jensen C, Maurer M, Grob J-J, Bülbül Baskan E, Bradley MS et al (2015) Efficacy and safety of omalizumab in patients with chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria who remain symptomatic on H1 antihistamines: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Invest Dermatol 135:67–75

Urgert MC, van den Elzen MT, Knulst AC, Fedorowicz Z, van Zuuren EJ (2015) Omalizumab in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria: a systematic review and GRADE assessment. Br J Dermatol 173:404–415

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 62:1006–1012

Higgins JPT, Green S (2011) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). http://handbook.cochrane.org/. Accessed 4 Feb 2016

Gagnier JJ, Kienle G, Altman DG, Moher D, Sox H, Riley D (2013) The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. Headache 53:1541–1547

Mansi M, Zanichelli A, Coerezza A, Suffritti C, Wu MA, Vacchini R et al (2015) Presentation, diagnosis and treatment of angioedema without wheals: a retrospective analysis of a cohort of 1058 patients. J Intern Med 277:585–593

Bouillet L, Boccon-Gibod I, Launay D, Gompe A, Kanny G, Fain O (2014) Hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor in a French cohort: clinical characteristics and response to treatment with icatibant. Allergy 69:52–53 (Congress abstract)

Bova M, Guilarte M, Sala-Cunill A, Borrelli P, Rizzelli GML, Zanichelli A (2015) Treatment of ACEI-related angioedema with icatibant: a case series. Intern Emerg Med 10:345–350

Greve J, Bas M, Hoffmann TK, Schuler PJ, Weller P, Kojda G et al (2015) Effect of C1-esterase-inhibitor in angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema. Laryngoscope 125:E198–E202

Hassen GW, Kalantari H, Parraga M, Chirurgi R, Meletiche C, Chan C et al (2013) Fresh frozen plasma for progressive and refractory angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema. J Emerg Med 44:764–772

Bartal C, Zeldetz V, Stavi V, Barski L (2015) The role of icatibant—the B2 bradykinin receptor antagonist—in life-threatening laryngeal angioedema in the ED. Am J Emerg Med 33:479.e1–e3

Lipski SM, Casimir G, Vanlommel M, Jeanmaire M, Dolhen P (2015) Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors-induced angioedema treated by C1 esterase inhibitor concentrate (Berinert®): about one case and review of the therapeutic arsenal. Clin Case Reports 3:126–130

Charmillon A, Deibener J, Kaminsky P, Louis G (2014) Angioedema induced by angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, potentiated by m-TOR inhibitors: successful treatment with icatibant. Intensive Care Med 40:893–894

Crooks NH, Patel J, Diwakar L, Smith FG (2014) Icatibant in the treatment of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema. Case Reports Crit Care 2014:1–3

Rasmussen ER, Mey K, Bygum A (2014) Isolated oedema of the uvula induced by intense snoring and ACE inhibitor. BMJ Case Rep 2014:1–3

Yates, C, Cordeiro MC, Crespi M, Puiguriguer J (2014) Successful treatment of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor angioedema with fresh frozen plasma. Clin Toxicol 52:407–408 (Congress abstract)

Bledsoe BE (2013) The swelling airway. Angioedema is not always caused by allergic reaction. JEMS 38:28–30

Volans A, Ferguson R (2013) Using a bradykinin blocker in ACE inhibitor-associated angioedema in the emergency department. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2012-008295

Bolton MR, Dooley-Hash SL (2012) Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor angioedema. J Emerg Med 43:e261–e262

Gallitelli M, Alzetta M (1664) Icatibant: a novel approach to the treatment of angioedema related to the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Am J Emerg Med 2012(30):e1–e2

Millot I, Plancade D, Hosotte M, Landy C, Nadaud J, Ragot C et al (2012) Tratment of a life-threatning laryngeal bradykinin angio-oedema precipitated by dipeptidylpeptidase-4 inhibitor and angiotensin-I converting enzyme inhibitor with prothrombin complex concentrates. Br J Anaesth 109:826–827 (Congress abstract)

Stewart M, McGlone R (2012) Fresh frozen plasma in the treatment of ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2012-006849

Baş M, Kojda G, Stelter K (2011) “Angiotensin-converting-enzyme”—Hemmer induziertes Angioödem. Anaesthesist 60:1141–1145

Schmidt PW, Hirschl MM, Trautinger F (2010) Treatment of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-related angioedema with the bradykinin B2 receptor antagonist icatibant. J Am Acad Dermatol 63:913–914

Dehne MG, Zimmer M, Deisz R, Bork K (2007) Angioödem durch C1-esterase-inhibitor-mangel oder ACE-hemmer? Anaesthesist 56:335–338

Nielsen EW, Gramstad S (2006) Angioedema from angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor treated with complement 1 (C1) inhibitor concentrate. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 50:120–122

Karim MY, Masood A (2002) Fresh frozen plasma as a treatment for life-threatning ACE-inhibitor angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol 109:370–371

Bertazzoni G, Bresciani E, Cipollone L, Fante E, Galandrini R (2015) Treatment with icatibant in the management of drug induced angioedema. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 19:149–153

Nanda A, Wasan AN (2014) Ecallantide in treatment of type III hereditary angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol 133:AB38

Stahl MC, Harris CK, Matto S, Bernstein JA (2014) Idiopathic nonhistaminergic angioedema successfully treated with ecallantide, icatibant, and C1 esterase inhibitor replacement. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2:818–819

Montinaro V, Loizzo G, Zito A, Castellano G, Gesualdo L (2013) Successful treatment of a facial attack of angioedema with icatibant in a patient with idiopathic angioedema. Am J Emerg Med 31:1295.e5–6

O’Keefe AW, McCusker C, Ben-Shoshan M (2013) Critical upper airway obstruction in sporadic angioedema responding to C1-esterase inhibitor. Case Rep 2013:bcr2013009616–bcr2013009616

Lleonart R, Andres B, Jacob J, Pasto L (2012) Treatment of idiopathic nonhistaminergic angioedema with icatibant

Weiler CR SS (2012) A case report of bradykinin receptorantagonist use in idiopathic non-histaminergic angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 109:A77

Vela Vizcaino C, Sola Enrique L, Chugo Gordillo S, Lizaso Bacaicoa MT, Caballero Molina T, García Figueroa BE (2014) Bradykinin-mediated hereditary angioedema (non-estrogen-dependant) without C1 inhibitor deficiency. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 24:280–281

Colás C, Montoiro R, Fraj J, Garcés M, Cubero J, Caballero T (2012) Nonhistaminergic idiopathic angioedema: clinical response to icatibant. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 22:529–531

Seoane M, Caralli ME, Micozzi S, Rodriguez-Mazariego ME, Baeza ML (2014) Incidence and treatment of angioedema in a third level Spanish hospital. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1:AB40 (Congress abstract)

Illing EJ, Kelly S, Hobson JC, Charters S (2012) Icatibant and ACE inhibitor angioedema. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2012-006646

Tran YD, de Malmanche T (2013) Management dilemmas in a case of angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor function during pregnancy. Intern Med J 43:1259–1259

Zazzali J, Rosen K, Bradley MS, Raimundo K (2014) Angioedema and angioedema management from Asteria I and Asteria II: phase III studies to evaluate the efficacy and safety of omalizumab in patients with chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria who remain symptomatic despite H1 antihistamine treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol 133:AB117 (Congress abstract)

Rijo Calderon Y, Palao P, Prior N, Fiandor A, Lopez-Serrano MC, Olalde S et al (2013) Treatment with off-label omalizumab in chronic idiopathic histaminergic urticaria—angioedema resistant to high doses of antihistamines. Allergy 68(Suppl 97):258 (Congress abstract)

Wintenberger C, Boccon-Gibod I, Launay D, Fain O, Kanny G, Jeandel PY et al (2014) Tranexamic acid as maintenance treatment for non-histaminergic angioedema: analysis of efficacy and safety in 37 patients. Clin Exp Immunol 178:112–117

Firinu D, Bafunno V, Vecchione G, Barca MP, Manconi PE, Santacroce R et al (2015) Characterization of patients with angioedema without wheals: the importance of F12 gene screening. Clin Immunol 157:239–248

Saule C, Boccon-Gibod I, Fain O, Kanny G, Plu-Bureau G, Martin L et al (2013) Benefits of progestin contraception in non-allergic angioedema. Clin Exp Allergy 43:475–482

Du-Tanh A, Raison-Peyron N, Drouet C, Guillot B (2009) Efficacy of tranexamic acid in sporadic idiopathic bradykinin angioedema. Allergy 65:792–793

Cicardi M, Bergamaschini L, Zingale LC, Gioffré D, Agostoni A (1999) Idiopathic nonhistaminergic angioedema. Am J Med 1999:650–654

Azofra J, Díaz C, Antépara I, Jaúregui I, Soriano A, Ferrer M (2015) Positive response to omalizumab in patients with acquired idiopathic nonhistaminergic angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 114:418–419e1

Sands MF, Blume JW, Schwartz SA (2007) Successful treatment of 3 patients with recurrent idiopathic angioedema with omalizumab. J Allergy Clin Immunol 120:977–979

Van Den Elzen MT, Röckmann H, Sanders CJG, Bruijnzeel-Koomen CAFM, Knulst AC (2014) Behandeling van chronische urticaria met omalizumab. Ned Tijdschr voor Dermatologie en Venereol 24:253–256

Groffik A, Mitzel-Kaoukhov H, Magerl M, Maurer M, Staubach P (2011) Omalizumab—an effective and safe treatment of therapy resistant chronic spontaneous urticaria. Allergy Eur J Allergy Clin Immunol 66:302–303

Büyüköztürk S, Gelincik A, Demirtürk M, Kocaturk E, Çolakoǧlu B, Dal M (2012) Omalizumab markedly improves urticaria activity scores and quality of life scores in chronic spontaneous urticaria patients: a real life survey. J Dermatol 39:439–442

Perez A, Woods A, Grattan CEH (2010) Methotrexate: a useful steroid-sparing agent in recalcitrant chronic urticaria. Br J Dermatol 162:191–194

Ghazanfar MN, Thomsen SF (2015) Successful and safe treatment of chronic spontaneous urticaria with omalizumab in a woman during two consecutive pregnancies. Case Rep Med 2015:368053

Wieder S, Maurer M, Lebwohl M (2015) Treatment of severely recalcitrant chronic spontaneous urticaria: a discussion of relevant issues. Am J Clin Dermatol 16:19–26

Kutlu A, Karabacak E, Aydin E, Ozturk S, Bozkurt B (2014) A patient with steroids and antihistaminic drug allergy and newly occurred chronic urticaria angioedema: what about omalizumab? Hum Exp Toxicol 33:882–885

Ozturk AB, Kocaturk E (2012) Omalizumab in recurring larynx angioedema: a case report. Asia Pac Allergy 2:76–85

Sánchez-Machín I, Iglesias-Souto J, Franco A, Barrios Y, Gonzalez R, Matheu V (2011) T cell activity in successful treatment of chronic urticaria with omalizumab. Clin Mol Allergy 9:11

Korkmaz H, Eigelshoven S, Homey B (2010) Omalizumab bei therapierefraktärer chronischer Urtikaria mit Angioödem. Hautarzt 61:828–831

Von Websky A, Reich K, Steinkraus V, Breuer K (2013) Complete remission of severe chronic recurrent angioedema of unknown cause with omalizumab. JDDG - J Ger Soc Dermatology 11:677–678

Suna B, Asli G, Ferhan O, Mustafa D, Sacide E, Bahattin C et al (2010) Successfull treatment of chronic idiopathic angioedema with omalizumab. Allergy 65(Suppl 92):459 (Congress abstract)

Bayer DK, DeGuzman M, Hanson IC (2013) Non-complement deficiency angioedema responsive to C1-inhibitor replacement. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 111:A71 (Congress abstract)

Maggadottir SM, Sullivan KE, Heimall J (2013) Case report of 2 patients with common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) and debilitating chronic urticaria/angioedema (CUA). J Clin Immunol 33:687 (Congress abstract)

Wu MA, Zanichelli A, Mansi M, Cicardi M (2016) Current treatment options for hereditary angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency. Expert Opin Pharmacother 17:27–40

Cicardi M, Banerji A, Bracho F, Malbrán A, Rosenkranz B, Riedl M et al (2010) Icatibant, a new bradykinin-receptor antagonist, in hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med 363:532–541

Cicardi M, Levy RJ, Mcneil DL, Li HH, Ph D, Sheffer AL et al (2010) Ecallantide for the treatment of acute attacks in hereditary angioedema. NEJM 363:523–531

Craig TJ, Levy RJ, Wasserman RL, Bewtra AK, Hurewitz D, Obtułowicz K et al (2009) Efficacy of human C1 esterase inhibitor concentrate compared with placebo in acute hereditary angioedema attacks. J Allergy Clin Immunol 124:801–808

Zuraw BL, Busse PJ, White M, Jacobs J, Lumry W, Baker J et al (2010) Nanofiltered C1 inhibitor concentrate for treatment of hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med 363:513–522

Zuraw B, Cicardi M, Levy RJ, Nuijens JH, Relan A, Visscher S et al (2010) Recombinant human C1-inhibitor for the treatment of acute angioedema attacks in patients with hereditary angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol 126:821–827.e14

Canadian Agency For Drugs And Technologies In Health (2015) Treatment of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema: guidelines (CADTH rapid response report: summary of abstracts). CADTH, Ottawa

Faisant C, Boccon-Gibod I, Mansard C, Dumestre Perard C, Pralong P, Chatain C et al. (2016) Idiopathic histaminergic angioedema without wheals: a case series of 31 patients. Clin Exp Immunol 185:81–85

Summary of product characteristics of omalizumab (Xolair®) 150 mg solution for injection. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/24912 and http://www.novartispharma.nl/pdf/ib/Xolair_150.pdf

Netherlands Pharmacovigilance Centre Lareb; WHO Collaborating Centre for Pharmacovigilance in Education and Patient Reporting. http://www.lareb.nl/

Assessment Report Kalbitor (ecallantide), procedure no.: EMEA/H/C/002200/. European Medicines Agency, London, 2011. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Application_withdrawal_assessment_report/human/002200/WC500122745.pdf

Product Monograph PrCYKLOKAPRON* (tranexamic acid); Tranexamic acid tablets BP and tranexamic acid injection BP. http://www.pfizer.ca/sites/g/files/g10017036/f/201410/Cyklokapron.pdf

Summary of product characteristics of methotrexate 10 mg tablets. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/12034

Weller K, Groffik A, Magerl M, Tohme N, Martus P, Krause K et al (2012) Development and construct validation of the angioedema quality of life questionnaire. Allergy 67:1289–1298

Weller K, Groffik A, Magerl M, Tohme N, Martus P, Krause K et al (2013) Development, validation, and initial results of the Angioedema Activity Score. Allergy 68:1185–1192

Weller K, Zuberbier T, Maurer M (2015) Chronic urticaria: tools to aid the diagnosis and assessment of disease status in daily practice. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol 29:38–44

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. C. Maas, Professor C.A.F.M. Bruijnzeel-Koomen, Professor C.E. Hack, and Andrew Walker for proofreading the manuscript.

Author Contributions

The study was designed by ME, HOM, and AK. Data were collected and extracted by ME, MG, and MB. Interpretation of data was performed by all authors. ME and MG prepared a first draft of the manuscript. HO, HOM, and AK contributed to finalizing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

M.T. van den Elzen has received speaker’s fees from Novartis. A.C. Knulst is a member of the national and international Novartis Omalizumab Advisory Council and has received speaker’s fees from Novartis and sponsoring for scientific studies from Novartis and Pharming. The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Funding

None.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

van den Elzen, M., Go, M.F.C.L., Knulst, A.C. et al. Efficacy of Treatment of Non-hereditary Angioedema. Clinic Rev Allerg Immunol 54, 412–431 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-016-8585-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-016-8585-0