Abstract

Background

Patient- and parent-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are increasingly used to evaluate the effectiveness of surgery for congenital hand differences (CHDs). Knowledge of an existing outcome measure’s ability to assess self-reported health, including psychosocial aspects, can inform the future development and application of PROMs for CHD. However, the extent to which measures used among children with CHD align with common, accepted metrics of self-reported disability remains unexplored.

Questions/purposes

We reviewed studies that used PROMs to evaluate surgery for CHD to determine (1) the number of World Health Organization-International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (WHO-ICF) domains covered by existing PROMs; (2) the proportion of studies that used PROMs specifically validated among children with CHD; and (3) the proportion of PROMs that targets patients and/or parents.

Methods

We performed a comprehensive review of the literature through a bibliographic search of MEDLINE®, PubMed, and EMBASE from January 1966 to December 2014 to identify articles related to patient outcomes and surgery for CHD. We evaluated the 42 studies that used PROMs to identify the number and type of WHO-ICF domains captured by existing PROMs for CHD and the proportion of studies that use PROMs validated for use among children with CHD. The most common instruments used to measure patient- and parent-reported outcomes after reconstruction for CHD included the Prosthetic Upper Extremity Functional Index (PUFI), Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand questionnaire, Childhood Experience Questionnaire, and Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory.

Results

Current PROMs that have been used for CHD covered a mean of 1.3 WHO-ICF domains (SD ± 1.3). Only the Child Behavior Checklist and the Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale captured all ICF domains (body functions and structures, activity, participation, and environmental factors). The PUFI, the only PROM validated specifically for children with congenital longitudinal and transverse deficiency, was used in only four of 42 studies. Only 13 of the 42 studies assessed patient-reported outcomes, whereas five assessed both patient- and parent-reported outcomes.

Conclusions

The PROMs used to assess patients after CHD surgery do not evaluate all WHO-ICF domains (ie, body structure, body function, environmental factors, and activity and participation) and generally are not validated for children with CHD. Given the psychological and sociological aspects of CHD illness, a PROM that encompasses all components of the biopsychosocial model of illness and validated in children with CHD is desirable.

Level of Evidence

Level III, therapeutic study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Congenital hand differences (CHDs) affect approximately one in every 600 newborns [59]. More than 10% of these children have partial or complete absence of the hand and functional losses are substantial [9]. Furthermore, children and their parents invariably experience considerable psychological stress from the appearance of the involved limb. Previous studies demonstrate that parents of children with CHD frequently mourn the loss of their expectations for their unborn child, and children with CHD have difficulty coping with the functional and aesthetic manifestations of these conditions [12, 30]. In this context, patient- and parent-reported outcome measures (PROMs) that can accurately and efficiently capture these experiences could provide important insight into the effect of CHDs on a child’s psychosocial functioning and development.

Many large series have reported substantial improvement in objective outcomes after surgery for CHD [29, 36, 48, 53, 54, 61–63]. However, the ultimate measure of success depends on more than the traditional measures of strength, sensibility, ROM, and time to task completion [1, 65]. In 2001, the World Health Organization developed the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (WHO-ICF) by which self-reported health can be considered and classified and consists of four domains: (1) body structure; (2) body function; (3) environmental factors; and (4) activity and participation [28]. Its purpose is to create an integrated biopsychosocial model of health status that accounts for environmental, sociodemographic, and psychological factors and to standardize descriptions of health and health-related status [79]. The biopsychosocial concept is a scientific model developed in the 1970s to account for the complex interplay of both medical and social factors that affect one’s health status [27]. The traditional biomedical model may be an effective way of measuring patient-reported outcomes but is limited by an inability to capture factors beyond the patient or disease process. Furthermore, because the biopsychosocial model categorizes self-reported health into discrete components, the ICF provides a clarifying framework for systematically reviewing the content of patient-reported outcome measures [51]. The use of a specific PROM can be assessed by examining the correlation between survey items and domains of this conceptual model [70].

The importance of patient and parent perspectives regarding disability and health status have been increasingly recognized, and PROMs are commonly used to evaluate the effectiveness of surgery for many conditions [6, 13, 18, 47, 60, 68]. However, prior research suggests that children’s experiences are not consistently elicited during clinical care, and providers more often engage parents during routine encounters [74, 75]. In turn, children may report feeling unheard and disconnected from providers [17, 32, 69] and, as a result, parent and child perceptions of outcomes, risks, and satisfaction are often discordant [24, 39, 57]. Therefore, understanding the extent to which child and parent perception of outcomes are captured is critical to develop effective and appropriate treatment plans.

To date, the extent to which PROMs are applied toward children with CHD is unclear, and the degree to which specific instruments accurately capture psychosocial functioning and disability is unknown. Understanding the ability of existing PROMs to assess such outcomes is critical to refine and improve these methods for future work. The purpose of this study is to determine (1) the number of WHO-ICF domains covered by existing PROMs; (2) the proportion of studies that used PROMs specifically validated among children with CHD; and (3) the proportion of PROMs that target patients and/or parents.

Search Strategy and Criteria

We performed a bibliographic search of MEDLINE®, PubMed, and EMBASE from January 1966 to December 2014 to identify articles related to patient outcomes after surgery for CHD. We used the phrases and keywords “brachydactyly”, “brachysyndactyly”, “camptodactyly”, “cleft hand”, “clinodactyly”, “congenital hand anomalies”, “congenital hand differences”, “congenital hand abnormalities”, “congenital clasped thumb”, “finger malformation”, “hand malformation”, “hand anomaly”, “hand deformities, congenital”, “mirror hand”, “pediatric hand anomalies”, “pediatric hand conditions”, “pediatric hand deformities”, “polydactyly”, “radial deficiency”, “radial longitudinal deficiency”, “radial dysplasia”, “syndactyly”, “thumb deficiency”, “thumb duplication”, “thumb hypoplasia”, and “thumb malformation”. We conducted a title and abstract search to identify appropriate articles using the following a priori criteria: original paper with primary patient outcomes; human subjects; English language publication published between January 1966 and December 2014; treatment included surgery for CHDs; and patient age at the time of surgery 0 to 18 years old. Additionally, we performed a manual reference check of the retrieved articles to capture additional references not initially captured by the original search. We excluded articles from review if they reported investigations of nonoperatively managed congenital hand differences, lacked patient- or parent-reported outcomes, or were from non-English language citations.

Data Extraction and Analysis

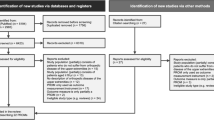

For our search, we used the selection process outlined by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Fig. 1). Our primary literature search identified 10,385 citations. Ultimately, 42 studies, including 1429 patients from 12 different countries, met inclusion criteria. Of these, 39 were cohort studies [2, 3, 5, 11, 12, 14–16, 19, 21–23, 26, 31, 33–35, 37, 38, 41, 44–46, 48, 50, 52, 56, 58, 62, 64, 66, 71–73, 76–78, 80, 82], two were cross-sectional studies [7, 43], and one was a case-control study [4].

After formal article review, two reviewers (JMA, RSB) independently extracted data from each study. These data included: study type, level of evidence, type of CHD, sample size, patient demographics, procedure performed, length of followup, domains and results of surgeon-generated ad hoc questionnaires, type, timing, and results of any patient- or parent-reported outcomes measure, clinical examination findings (when available), and ICF domain comparison for validated PROMs (Table 1).

Surgeon-generated ad hoc questionnaires were used in 36 studies. Most commonly, surgeon-generated questionnaires assessed satisfaction, appearance, function, social implications, psychosocial well-being, task performance, and pain. Objective outcomes measures most commonly evaluated included ROM, grip and pinch strength, tests of hand function (eg, Jebsen-Taylor, dexterity), sensibility, contour, and radiographic appearance (Table 2; Appendix 1 [Supplemental materials are available with the online version of CORR®]).

Results

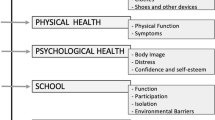

The PROMs identified in this study covered a mean of 1.3 WHO-ICF domains (SD ± 1.3). These domains include body functions and structures, activity, participation, and environmental factors. Body functions and structures were assessed by 12 of 19 validated measures, whereas 11 captured activity, 11 captured participation, and only six captured environmental factors. Only the Child Behavior Checklist [14] and Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale [4] captures all four ICF domains. Nine PROMs evaluated only one ICF domain.

Of the 19 validated PROMs used in the 42 studies, only the Prosthetic Upper Extremity Functional Index (PUFI) has been validated specifically in the CHD population (children with congenital longitudinal and transverse deficiency) [7, 8, 22, 48]. Only the ABILHAND-Kids Questionnaire, Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH), Pediatric Outcomes Data Collection Instrument, PUFI, and QuickDASH were developed specifically for use in patients with orthopaedic/upper extremity pathology [7, 8, 22, 26, 35, 44, 48, 72]. The remaining PROMs were developed and validated as generic adult or pediatric outcomes measures. Validated PROMs were used to assess radial longitudinal deficiency (n = 5), microvascular free toe-to-hand transfer (n = 3), all congenital anomalies (n = 2), thumb duplication (n = 2), and macrodactyly (n = 1) (Table 2). The PUFI was used in four studies, the DASH was used in three studies, and the Childhood Experience Questionnaire and Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory were both used in two studies. The remaining instruments were used once.

Patient-reported outcomes measures were used in 13 of the 42 studies. Seven of these 13 studies used more than one instrument and a single study used six different PROMs. Parent-reported outcomes measures were used in six of the 42 studies. Both patient- and parent-reported outcomes were reported in five of the 42 studies.

Discussion

Congenital hand differences profoundly affect a child’s physical and psychological development. Although prior research has largely focused on outcomes using objective, functional measures, PROMs capture and quantify the experience of the patient and parents. Ideally, PROMs used to study treatments for CHD would assess psychosocial aspects of the illness as well as symptom intensity and magnitude of disability. In other words, the PROM would address all the WHO-ICF domains. Our purpose was to determine the number of WHO-ICF domains covered by PROMs used in the study of treatments for CHD, the proportion of studies that use PROMs specifically validated among children with CHD, and the proportion of PROMs that target parents, patients, or both.

Our study has several limitations that should be noted. First, CHDs are relatively uncommon, and few studies specifically use PROMs when reporting outcomes for these rare conditions. Additionally, the quality of our findings relies on the quality of the studies included, and these studies vary in the way in which instruments were administered and the study samples that were included. Therefore, we cannot aggregate our data to examine summary effects. Our search only included published articles; other sources such as conference proceedings or unpublished data are not reflected in this review. In this way, there may be newer instruments under development that remain heretofore unexplored but may subsequently emerge to be important measures for future study.

Our review identified that current PROMs used to evaluate patients after surgery for CHD do not fully capture important disability domains as defined by the WHO-ICF framework. This finding likely results from a limited recognition of the impact of psychosocial function on overall health and well-being among those who create survey instruments relevant for children with CHD. Although this four-part model may only provide a broad framework for conceptualizing disability, it likely offers a better overall assessment of how a child with a CHD functions in daily life as compared with alternative measures that focus only on body function/structure or activities. Psychosocial function is highly relevant for children with CHD [42, 81]. In fact, Franzblau et al. [30] found that 58% of children and 40% of parents reported stress related to their CHD. The authors found that 58% of this stress resulted from social interactions, 46% resulted from emotional reactions, and 27% resulted from hand appearance. These factors may be more reliably assessed using a measure designed using the WHO-ICF framework. To this end, disability measures can provide a better assessment of the true outcomes of surgery. Therefore, consideration for each component is important to understand how children and their families experience life with CHD and what elements of disability can and should be addressed with surgery.

Most PROMs we found are not validated for children with CHD. To address the lack of disease-specific items of many of the generic PROMs outcomes instruments, surgeon-generated questionnaires are frequently used. Although these measures provide greater detail regarding outcomes specific to CHD such as web space creep, scarring, and difficulty with specific tasks (eg, buttoning shirts, using scissors), the use of surgeon-generated ad hoc instruments can be problematic. Their frequent use is understandable given that high-quality outcomes measures are extremely complex and require statistical expertise and clinical experience for both creation and application [55]. Surgeon-generated questionnaires are often developed to answer a specific clinical question in the setting of scant resources with a limited emphasis on proper development or validation [10]. If one is to report survey instrument findings, ensuring that the instrument has been validated in the population of interest is an important component of confident data reporting. Furthermore, the ad hoc nature of these instruments generally limits their ability to be used more broadly across other samples and centers for comparability [25]. For example, in our review, only four instruments have been used more than once. As such, it remains difficult to synthesize data across studies using different instruments given the lack of standardized outcomes.

In our review, the majority of PROMs focused on parent-, not patient-reported outcomes for several possible reasons. First, proposed age guidelines for PROMs depend on instrument complexity and the availability of trained assistants for children who may have difficulty reading the material or interpreting a question [20]. In children who are cognitively impaired or otherwise unable to understand survey items, validated parent-proxy reports are available, and many studies record only parent-reported outcomes data. However, discrepancies between child- and parent-reported outcomes have been noted in previous studies with parents either overestimating or underestimating the impact of CHD on their children [2, 3, 8, 10, 40, 44, 55]. One possible way to evaluate the reliability of a proxy report is to administer the exact same PROM in a parallel fashion to both the parental proxy and the child. The correlation between survey responses can be assessed by examining the response means, SDs, and an intraclass correlation coefficient (> 0.7 is considered to be a marker of answer reliability). Second, determining the most appropriate metrics for this unique patient population remains challenging. For example, many outcomes instruments are designed to measure recovery from an injury or some other alteration from a “nondiseased” physical state. Children with CHD have no “normal” baseline with which to compare their current physical and psychological condition. This limitation is further compounded by the substantial adaptability among pediatric patients [4]. In other words, the degree to which a child is affected by a CHD may evolve over time as the child learns to adapt and cope. As such, existing instruments may inadequately measure clinically meaningful differences in long-term outcomes. Lastly, control groups are rarely included in these studies and comparisons with normative data collected during instrument development are typically used. No instruments are available that have been validated in children younger than 5 years of age.

An instrument that captures all the important aspects of biopsychosocial functioning for children with CHD and their families and that is feasible and efficient to administer remains elusive. An ideal PROM for children with CHD would include disease- and age-relevant questions across the full scope of the four WHO-ICF domains. These questions can be based on the comprehensive and brief ICF Core Sets for Hand Conditions developed in 2012 by the multidisciplinary WHO International Consensus Group [67]. The relevance of the survey questions in these Core Sets has been demonstrated [49] and the use of these items allows for a direct content comparison to other measures [28]. Using these categories (eg, emotional functions [body functions], structure of upper extremity [body structures], fine hand use [activities and participation], support and relationships [environmental factors]), a survey may be developed that comprehensively examines the health and well-being of children with CHD. Finally, future studies could explore the need to validate and refine parent-proxy versions that could be used for children who are unable to complete self-reported measures as a result of age or cognitive difficulties.

In conclusion, our systematic review revealed broad heterogeneity in the available PROMs used to capture outcomes among children who have undergone surgery for CHD. Given the profound psychological and sociological sequelae of CHD, a PROM that comprehensively evaluates all biopsychosocial components of disability and is validated for use among children with CHD will improve our ability to measure the effectiveness of treatment and quality of care.

References

Aaron DH, Jansen CW. Development of the Functional Dexterity Test (FDT): construction, validity, reliability, and normative data. J Hand Ther. 2003;16:12–21.

Abdel-Ghani H, Amro S. Characteristics of patients with hypoplastic thumb: a prospective study of 51 patients with the results of surgical treatment. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2004;13:127–138.

Aliu O, Netscher DT, Staines KG, Thornby J, Armenta A. A 5-year interval evaluation of function after pollicization for congenital thumb aplasia using multiple outcome measures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:198–205.

Andersson GB, Gillberg C, Fernell E, Johansson M, Nachemson A. Children with surgically corrected hand deformities and upper limb deficiencies: self-concept and psychological well-being. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2011;36:795–801.

Andrew JG, Sykes PJ. Duplicate thumbs: a survey of results in twenty patients. J Hand Surg Br. 1988;13:50–53.

Appleby J, Poteliakhoff E, Shah K, Devlin N. Using patient-reported outcome measures to estimate cost-effectiveness of hip replacements in English hospitals. J R Soc Med. 2013;106:323–331.

Ardon MS, Janssen WG, Hovius SE, Stam HJ, Selles RW. Low impact of congenital hand differences on health-related quality of life. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93:351–357.

Ardon MS, Selles RW, Roebroeck ME, Hovius SE, Stam HJ, Janssen WG. Poor agreement on health-related quality of life between children with congenital hand differences and their parents. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93:641–646.

Bates SJ, Hansen SL, Jones NF. Reconstruction of congenital differences of the hand. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(Suppl):128e–143e.

Bayliss EA, Ellis JL, Shoup JA, Zeng C, McQuillan DB, Steiner JF. Association of patient-centered outcomes with patient-reported and ICD-9-based morbidity measures. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:126–133.

Bellew M, Haworth J, Kay SP. Toe to hand transfer in children: ten year follow up of psychological aspects. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:766–775.

Bellew M, Kay SP. Psychological aspects of toe to hand transfer in children. Comparison of views of children and their parents. J Hand Surg Br. 1999;24:712–718.

Bourne RB, Chesworth BM, Davis AM, Mahomed NN, Charron KD. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: who is satisfied and who is not? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:57–63.

Bradbury ET, Kay SP, Hewison J. The psychological impact of microvascular free toe transfer for children and their parents. J Hand Surg Br. 1994;19:689–695.

Buffart LM, Roebroeck ME, Janssen WG, Hoekstra A, Selles RW, Hovius SE, Stam HJ. Hand function and activity performance of children with longitudinal radial deficiency. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:2408–2415.

Ceulemans L, Degreef I, Debeer P, De Smet L. Outcome of index finger pollicisation for the congenital absent or severely hypoplastic thumb. Acta Orthop Belg. 2009;75:175–180.

Chesney M, Lindeke L, Johnson L, Jukkala A, Lynch S. Comparison of child and parent satisfaction ratings of ambulatory pediatric subspecialty care. J Pediatr Health Care. 2005;19:221–229.

Chung KC, Burke FD, Wilgis EF, Regan M, Kim HM, Fox DA. A prospective study comparing outcomes after reconstruction in rheumatoid arthritis patients with severe ulnar drift deformities. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:1769–1777.

Clark DI, Chell J, Davis TR. Pollicisation of the index finger. A 27-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80:631–635.

de Jong IG, Reinders-Messelink HA, Janssen WG, Poelma MJ, van Wijk I, van der Sluis CK. Mixed feelings of children and adolescents with unilateral congenital below elbow deficiency: an online focus group study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37099.

de Kraker M, Selles RW, van Vooren J, Stam HJ, Hovius SE. Outcome after pollicization: comparison of patients with mild and severe longitudinal radial deficiency. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131:544e–551e.

Dijkman RR, van Nieuwenhoven CA, Selles RW, Hovius SE. Comparison of functional outcome scores in radial polydactyly. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:463–470.

Do V, Trzcinski D, Rayan G. Perception of the esthetic and functional outcomes of duplicate thumb reconstruction. Hand (N Y). 2013;8:282–290.

Eiser C, Morse R. Can parents rate their child’s health-related quality of life? Results of a systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2001;10:347–357.

Eiser C, Varni JW. Health-related quality of life and symptom reporting: similarities and differences between children and their parents. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172:1299–1304.

Ekblom AG, Laurell T, Arner M. Epidemiology of congenital upper limb anomalies in 562 children born in 1997 to 2007: a total population study from Stockholm, Sweden. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35:1742–1754.

Engel GL. The need for a new model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129–136.

Forget NJ, Higgins J. Comparison of generic patient-reported outcome measures used with upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders: linking process using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health J Rehabil Med. 2014;46:327–334.

Foucher G, Medina J, Pajardi G, Navarro R. [Classification and treatment of symbrachydactyly. A series of 117 cases] [in French]. Chir Main. 2000;19:161–168.

Franzblau LE, Chung KC, Carlozzi N, Nellans KW, Waljee JF. Coping with congenital hand differences. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135:1067–75.

Ganley TJ, Lubahn JD. Radial polydactyly: an outcome study. Ann Plast Surg. 1995;35:86–89.

Garth B, Murphy GC, Reddihough DS. Perceptions of participation: child patients with a disability in the doctor-parent-child partnership. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74:45–52.

Goldfarb CA, Chia B, Manske PR. Central ray deficiency: subjective and objective outcome of cleft reconstruction. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33:1579–1588.

Goldfarb CA, Deardorff V, Chia B, Meander A, Manske PR. Objective features and aesthetic outcome of pollicized digits compared with normal thumbs. J Hand Surg. 2007;32:1031–1036.

Goldfarb CA, Klepps SJ, Dailey LA, Manske PR. Functional outcome after centralization for radius dysplasia. J Hand Surg Am. 2002;27:118–124.

Goldfarb CA, Monroe E, Steffen J, Manske PR. Incidence and treatment of complications, suboptimal outcomes, and functional deficiencies after pollicization. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34:1291–1297.

Goldfarb CA, Patterson JM, Maender A, Manske PR. Thumb size and appearance following reconstruction of radial polydactyly. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33:1348–1353.

Goldfarb CA, Steffen JA, Stutz CM. Complex syndactyly: aesthetic and objective outcomes. J Hand Surg. 2012;37:2068–2073.

Gutierrez-Colina AM, Eaton CK, Lee JL, LaMotte J, Blount RL. Health-related quality of life and psychosocial functioning in children with tourette syndrome: parent-child agreement and comparison to healthy norms. J Child Neurol. 2015;30:326–332.

Hadders-Algra M, Reinders-Messelink HA, Huizing K, van den Berg R, van der Sluis CK, Maathuis CG. Use and functioning of the affected limb in children with unilateral congenital below-elbow deficiency during infancy and preschool age: a longitudinal observational multiple case study. Early Hum Dev. 2013;89:49–54.

Hardwicke J, Khan MA, Richards H, Warner RM, Lester R. Macrodactyly–options and outcomes. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2013;38:297–303.

Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Masek B, Henin A, Blakely LR, Pollock-Wurman RA, McQuade J, DePetrillo L, Briesch J, Ollendick TH, Rosenbaum JF, Biederman J. Cognitive behavioral therapy for 4- to 7-year-old children with anxiety disorders: a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78:498–510.

Holtslag I, van Wijk I, Hartog H, van der Molen AM, van der Sluis C. Long-term functional outcome of patients with longitudinal radial deficiency: cross-sectional evaluation of function, activity and participation. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35:1401–1407.

Kaplan JD, Jones NF. Outcome measures of microsurgical toe transfers for reconstruction of congenital and traumatic hand anomalies. J Pediatr Orthop. 2014;34:362–368.

Kay SP, Wiberg M. Toe to hand transfer in children. Part 1: technical aspects. J Hand Surg Br. 1996;21:723–734.

Kemnitz S, De SL. Pre-axial polydactyly: outcome of the surgical treatment. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2002;11:79–84.

Kotsis SV, Chung KC. Responsiveness of the Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire and the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand questionnaire in carpal tunnel surgery. J Hand Surg Am. 2005;30:81–86.

Kotwal PP, Varshney MK, Soral A. Comparison of surgical treatment and nonoperative management for radial longitudinal deficiency. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2012;37:161–169.

Kus S, Oberhauser C, Cieza A. Validation of the brief International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) core set for hand conditions. J Hand Ther. 2012;25:274–286.

Larsen M, Nicolai JP. Long-term follow-up of surgical treatment for thumb duplication. J Hand Surg Br. 2005;30:276–281.

Lindner HY, Natterlund BS, Hermansson LM. Upper limb prosthetic outcome measures: review and content comparison based on International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2010;34:109–128.

Lumenta DB, Kitzinger HB, Beck H, Frey M. Long-term outcomes of web creep, scar quality, and function after simple syndactyly surgical treatment. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35:1323–1329.

Manske PR, McCarroll HR Jr. Abductor digiti minimi opponensplasty in congenital radial dysplasia. J Hand Surg Am. 1978;3:552–559.

Manske PR, Rotman MB, Dailey LA. Long-term functional results after pollicization for the congenitally deficient thumb. J Hand Surg Am. 1992;17:1064–1072.

McKenna SP. Measuring patient-reported outcomes: moving beyond misplaced common sense to hard science. BMC Med. 2011;9:86.

Mei H, Zhu G, He R, Liu K, Wu J, Tang J. The preliminary outcome of syndactyly management in children with a new external separation device. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2015;24:56–62.

Nauta MH, Scholing A, Rapee RM, Abbott M, Spence SH, Waters A. A parent-report measure of children’s anxiety: psychometric properties and comparison with child-report in a clinic and normal sample. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42:813–839.

Netscher DT, Aliu O, Sandvall BK, Staines KG, Hamilton KL, Salazar-Reyes H, Thornby J. Functional outcomes of children with index pollicizations for thumb deficiency. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38:250–257.

Netscher DT, Baumholtz MA. Treatment of congenital upper extremity problems. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:101e–129e.

Noble PC, Conditt MA, Cook KF, Mathis KB. The John Insall Award: Patient expectations affect satisfaction with total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;452:35–43.

Oda T, Pushman AG, Chung KC. Treatment of common congenital hand conditions. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:121e–133e.

Ogino T, Ishii S, Takahata S, Kato H. Long-term results of surgical treatment of thumb polydactyly. J Hand Surg Am. 1996;21:478–486.

Ozalp T, Coskunol E, Ozdemir O. [Thumb duplication: an analysis of 72 thumbs] [in Turkish]. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2006;40:388–391.

Patel AU, Tonkin MA, Smith BJ, Alshehri AH, Lawson RD. Factors affecting surgical results of Wassel type IV thumb duplications. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2014;39:934–943.

Pruitt SD, Varni JW, Setoguchi Y. Functional status in children with limb deficiency: development and initial validation of an outcome measure. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:1233–1238.

Roper BA, Turnbull TJ. Functional assessment after pollicisation. J Hand Surg Br. 1986;11:399–403.

Rudolph KD, Kus S, Chung KC, Johnston M, LeBlanc M, Cieza A. Development of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health core sets for hand conditions–results of the World Health Organization International Consensus process. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:681–693.

Sammer DM, Fuller DS, Kim HM, Chung KC. A comparative study of fragment-specific versus volar plate fixation of distal radius fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:1441–1450.

Sonneveld HM, Strating MM, van Staa AL, Nieboer AP. Gaps in transitional care: what are the perceptions of adolescents, parents and providers? Child Care Health Dev. 2013;39:69–80.

Squitieri L, Reichert H, Kim HM, Chung KC. Application of the brief international classification of functioning, disability, and health core set as a conceptual model in distal radius fractures. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35:1795–1805.e1791.

Staines KG, Majzoub R, Thornby J, Netscher DT. Functional outcome for children with thumb aplasia undergoing pollicization. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1314–1323; discussion 1324-1325.

Stutz C, Mills J, Wheeler L, Ezaki M, Oishi S. Long-term outcomes following radial polydactyly reconstruction. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39:1549–1552.

Tan JS, Tu YK. Comparative study of outcomes between pollicization and microsurgical second toe-metatarsal bone transfer for congenital radial deficiency with hypoplastic thumb. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2013;29:587–592.

Tates K, Meeuwesen L. ‘Let mum have her say’: turntaking in doctor-parent-child communication. Patient Educ Couns. 2000;40:151–162.

Tates K, Meeuwesen L, Elbers E, Bensing J. ‘I’ve come for his throat’: roles and identities in doctor-parent-child communication. Child Care Health Dev. 2002;28:109–116.67.

Tonkin MA, Boyce DE, Fleming PP, Filan SL, Vigna N. The results of pollicization for congenital thumb hypoplasia. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2015;40:620–624.

Unglaub F, Lanz U, Hahn P. Outcome analysis, including patient and parental satisfaction, regarding nonvascularized free toe phalanx transfer in congenital hand deformities. Ann Plast Surg. 2006;56:87–92.

Vekris MD, Beris AE, Lykissas MG, Soucacos PN. Index finger pollicization in the treatment of congenitally deficient thumb. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;66:137–142.

World Health Organization. World Health Organization International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2001.

Yen CH, Chan WL, Leung HB, Mak KH. Thumb polydactyly: clinical outcome after reconstruction. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2006;14:295–302.

Ylimainen K, Nachemson A, Sommerstein K, Stockselius A, Norling Hermansson L. Health-related quality of life in Swedish children and adolescents with limb reduction deficiency. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99:1550–1555.

Zlotolow DA, Tosti R, Ashworth S, Kozin SH, Abzug JM. Developing a pollicization outcomes measure. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39:1784–1791.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This project was supported, in part, by a National Institutes of Health, Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-oriented Research (K24 AR053120-6) (KCC) and the Michigan Institute for Clinical Health Research MICHR/CTSA Pilot Grant (JFW).

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research ® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

This work was performed at the Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA, and The University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

About this article

Cite this article

Adkinson, J.M., Bickham, R.S., Chung, K.C. et al. Do Patient- and Parent-reported Outcomes Measures for Children With Congenital Hand Differences Capture WHO-ICF Domains?. Clin Orthop Relat Res 473, 3549–3563 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-015-4505-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-015-4505-5