Abstract

Background

There has been increasing evidence to support the importance of psychosocial factors to poor outcomes after trauma. However, little is known about the contribution of pain catastrophizing and fear of movement to persistent pain and disability.

Questions/purposes

Therefore, we aimed to determine whether (1) high pain catastrophizing scores are independently associated with pain intensity or pain interference; (2) high fear of movement scores are independently associated with decreased physical health; and (3) depressive symptoms are independently associated with pain intensity, pain interference, or physical health at 1 year after accounting for patient characteristics of age and education.

Methods

Of 207 eligible patients, we prospectively enrolled 134 patients admitted to a Level I trauma center for surgical treatment of a fracture to the lower extremity. Sixty percent of patients (80 of 134) had an isolated lower extremity injury and the remainder sustained additional minor injury to the head/spine, abdomen/thorax, or upper extremity. Pain catastrophizing was measured with the Pain Catastrophizing Scale, fear of movement with the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia, and depressive symptoms with the Patient Health Questionnaire. Pain and physical health outcomes were assessed with the Brief Pain Inventory and the SF-12, respectively. Assessments were completed at 4 weeks and 1 year after hospitalization. Multiple variable hierarchical linear regression analyses were used to address study hypotheses. One hundred ten patients (82%) completed the 1-year followup.

Results

Pain catastrophizing at 4 weeks was associated with pain intensity (β = 0.67; p < 0.001) and pain interference (β = 0.38; p = 0.03) at 1 year. No association was found between fear of movement and physical health (β = 0.15; p = 0.34). Depressive symptoms at 4 weeks were associated with pain intensity (β = 0.49; p < 0.001), pain interference (β = 0.51; p < 0.001), and physical health (β = −0.32; p = 0.01) at 1 year.

Conclusions

Catastrophizing behavior patterns and depressive symptoms are associated with more severe pain and worse function after traumatic lower extremity injury. Cognitive and behavioral strategies that have proven effective for chronic pain populations may be beneficial for trauma patients. Future research is needed to determine whether the early identification and treatment of subgroups of at-risk patients based on catastrophizing behavior or depressive symptoms can improve long-term outcomes.

Level of Evidence

Level I, prognostic study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The persistence of moderate to severe pain is common in patients after traumatic injury. Studies report levels of moderate to severe pain in 48% to 59% of trauma survivors at hospital discharge [3, 65], 37% to 56% of patients within 6 months postinjury [10, 11], and 63% at 1 year after major trauma [47]. The Lower Extremity Assessment Project found that 73% of patients reported pain 7 years after traumatic lower extremity injury [10]. Trauma survivors also experience profound levels of physical disability and difficulty returning to productive employment [7, 34, 35]. Patient-reported quality-of-life scores are consistently below the health norm for adult populations [22, 58], 40% to 50% report moderate levels of disability [1, 7], and 35% to 50% have delayed return to work up to 24 months after injury [7, 39, 45].

There has been increasing evidence to support the importance of psychosocial factors to poor outcomes after trauma. A systematic review found moderate evidence of an association between depressive symptoms during the early recovery period and persistent pain [12]. Wegener and colleagues [63] demonstrated that as the recovery process proceeds, physical function is increasingly influenced by depression and anxiety related to the pain experience.

Pain catastrophizing (defined as the tendency to focus on, ruminate, and magnify pain sensations) and fear of movement are potentially important psychosocial factors for the development of chronic pain and physical disability in trauma survivors. Robust evidence supports an association between pain catastrophizing and the severity of postoperative pain [27]. More specifically, pain catastrophizing has been found to be an important predictor of increased pain after knee arthroplasty [46, 51]. Fear of movement has also demonstrated an important relationship with poor health outcomes in patients with various musculoskeletal conditions [16, 57]. In patients who have experienced orthopaedic trauma, little is known about these specific psychosocial risk factors. Archer et al. [2] demonstrated that pain catastrophizing was associated with pain intensity, pain interference, and physical health 2 years after traumatic injury. Three studies have found that patients who display catastrophizing behavior are at risk for more severe pain and disability up to 12 months after trauma [19, 42, 60].

This study had three specific objectives. The first aim was to determine whether high pain catastrophizing scores are independently associated with pain intensity or pain interference at 1 year after hospital discharge for a traumatic lower extremity injury after accounting for patient characteristics of age and education. The second aim was to determine whether high fear of movement scores are independently associated with decreased physical health at 1 year. The third aim was to determine whether depressive symptoms are independently associated with pain intensity, pain interference, or physical health at 1 year.

Patients and Methods

This study was a prospective cohort study of patients admitted to a Level I trauma center for surgical treatment of a traumatic lower extremity injury between November 2009 and March 2011.

Eligible participants were identified from the medical record and approached at an early postoperative clinic visit. Inclusion criteria included: (1) age older than 18 years; (2) admitted for an acute traumatic event; (3) undergoing surgery for fracture of the lower extremity using open reduction and internal fixation; (4) Glasgow Coma Score equal to 15 on admission; and (5) length of hospital stay greater than 24 hours. Patients with intracranial hemorrhage indicating moderate to severe brain injury, spinal cord deficit, a documented history of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorder, or surgery for an extremity amputation were excluded.

Four hundred patients were examined for eligibility and 207 were eligible and approached on weekdays and nonholidays. Of the 207 eligible patients approached, 134 (65%) agreed to participate and were enrolled (Table 1). One hundred ten patients (82%) completed the 1-year followup. There were no significant differences in age, sex, race, education, employment, marital status, insurance, comorbid conditions, mechanism of injury, primary injury, hospital length of stay, and Injury Severity Score (ISS) between patients with and without complete followup data.

Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants after institutional review board approval. Patients completed a questionnaire in person that contained demographic questions and validated measures of pain catastrophizing, fear of movement, depressive symptoms, pain intensity and interference, and physical health 4 weeks after hospital discharge. A followup assessment was conducted at 1 year to gather data on pain and physical health outcomes. Assessments were mailed to those patients not returning to the clinic. If a person did not respond within 1 week after mailing the questionnaire, patients were contacted by telephone and asked to complete and return the questionnaire within 5 days. Mechanism of injury, type of injury, length of hospital stay, and ISS were abstracted from the medical record.

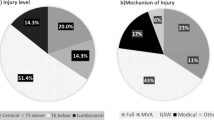

The mean age was 45 years (SD = 15) and the majority of study participants were male (70 of 134 [52%]), white (126 of 134 [94%]), and had less than or equal to a high school education (68 of 134 [51%]) (Table 1). Fifty-one percent of patients were treated for a motor vehicle accident (69 of 134) and 60% were hospitalized for isolated lower extremity injuries (80 of 134). The remainder sustained additional minor injury, not requiring surgery, to the head or spine (25 of 134 [19%]), abdomen or thorax (15 of 134 [11%]), and upper extremity (14 of 134 [10%]). Primary injury included tibia (53 of 134 [40%]), femoral shaft (28 of 134 [21%]), ankle (20 of 134 [15%]), distal femur (18 of 134 [13%]), and foot (15 of 134 [11%]).

Moderate to severe pain catastrophizing and high fear of movement were reported in 21% (28 of 134) and 65% (87 of 134) of the patients, respectively (Table 2). Presence of depressive symptoms was reported in 38% (51 of 134) of patients with 23% (31 of 134) indicating no preexisting depression diagnosis.

Psychosocial Factors

Pain catastrophizing was assessed with the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) [50]. Participants rate items on a 5-point scale with the endpoints “not at all” and “all the time.” A total score ranges from 0 to 52, and a score greater than 24 differentiates between “catastrophizers” and “noncatastrophizers.” The PCS has demonstrated strong internal consistency, high test-retest reliability, and validity through associations with pain, disability, negative affect, and pain-related fear [18, 44, 50].

The 17-item Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK) was used to measure fear of movement [28]. The TSK is a 17-item instrument with scoring options ranging from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 4 = “strongly agree.” A total score is calculated and can range from 17 to 68. A score greater than 39 differentiates between high and low scores [41, 56]. The TSK has been found to be a reliable index of fear of movement/(re)injury and to have good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.70) and test-retest reliability (Pearson’s r > 0.70) [8, 17].

Depressive symptoms were measured with the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [29]. This instrument was developed using the diagnostic criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). The PHQ-9 scores each of the DSM-IV criteria as 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“nearly everyday”) and a total score ranges from 0 to 27. PHQ-9 scores of 5, 10, 15, and 20 represent mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe depression, respectively [29]. In a psychometric study of the PHQ-9 compared with independent diagnoses made by mental health professionals, the instrument was both sensitive (0.75) and specific (0.90) for the diagnosis of major depression [49]. Internal reliability scores have been estimated at 0.89 in a primary care population [29]. A score of 10 or higher has been recommended as a cutoff for clinically significant depression and has been found to have sensitivity and specificity of 88% for major depression [29].

Pain and Physical Health Outcomes

The Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) was used to measure pain intensity and pain interference [13]. The four-item pain intensity scale measures current, worst, least, and average pain. The remaining seven items assess general activity, mood, walking, work, relations with others, sleep, and enjoyment of life. Numeric scales rate items from 0 to 10 with 0 being “no pain or no interference” and 10 being “severe pain or severe interference.” The BPI has proven reliable (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.80) and valid through strong correlations with the SF-36 pain scale and the Visual Analog Scale for pain in patients with postoperative pain [38, 67].

Physical health was measured with the physical component scale (PCS) of the SF-12 [62]. Scores range from 0 to 100 with 0 indicating worst health. The physical subscale assesses physical functioning, role limitations resulting from physical health problems, bodily pain, and general health perceptions. The PCS of the SF-12 has demonstrated responsiveness, good test–retest reliability (Pearson’s r > 0.75), good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.70), and validity with correlations greater than 0.90 with the SF-36 in generalized and various patient populations [23, 33, 62].

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize all study variables (means, medians, SDs, frequency). All continuous variables were examined for the assumptions required for parametric analyses. Differences between responders and nonresponders at 1 year after hospital discharge were examined with Student’s t-tests and Fisher’s exact tests. Pearson correlation coefficients with a Bonferroni correction were used to examine bivariate associations among pain catastrophizing, fear of movement, depressive symptoms, and outcome variables (pain intensity, pain interference, and physical health). Separate bivariate linear regression analyses were used to assess the relationship between demographic and clinical characteristics and outcomes.

Multiple variable hierarchical linear regression (HLR) [14] analyses were performed to determine whether pain catastrophizing, fear of movement, and depressive symptoms were independently associated with each outcome variable. Models controlled for patients characteristics that were significant at p < 0.05 in bivariate analyses and the outcome of interest at baseline (ie, 4 weeks after hospital discharge). In each HLR model, patient characteristics were entered first (Step 1), psychosocial factors were entered second (Step 2), and the outcome at baseline was entered third (Step 3) [52]. The estimate of the separate variance accounted for by each variable was reported using the adjusted partial σ 2. To control for multicollinearity in the models, variance inflation factors were determined for the independent variables and had to be below 10 [40]. Stata statistical software (Version 11.0; Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA) was used to analyze the data. The level of significance was set at α = 0.05.

The number of study participants for this study was based on a sample size calculation for a multiple variable linear regression. The estimate was based on the multiple correlation coefficients that are obtained when all variables are included in the regression model and only the independent variables of interest are included. Using a conservative R2 for the full model of 0.30 and R2 for the variables of interest of 0.10, alpha level of 0.05, power of 0.90, and controlling for six independent variables, a sample size of at least 92 was needed to detect an association between pain catastrophizing, fear of movement, and depressive symptoms and patient-reported outcomes. A larger sample size was recruited to account for a 70% followup rate.

Results

Our data indicate strong correlations between pain catastrophizing scores at 4 weeks and pain intensity (σ = 0.75; p < 0.001) and pain interference (σ = 0.60; p < 0.001) at 1 year (Table 3). These relationships were maintained after taking into account potential confounders. We found that patients with high pain catastrophizing scores at 4 weeks had worse pain intensity (β = 0.67; p < 0.001) and pain interference (β = 0.38; p = 0.03) at 1 year compared with patients with low pain catastrophizing scores after adjusting for age, education, fear of movement, depressive symptoms, and pain at 4 weeks (Table 4). Results suggest that for every 10-point increase in pain catastrophizing scores (range, 0–52) at 4 weeks, there was a 6.7-point and 3.8-point increase in pain intensity and pain interference (range, 0–10), respectively, at 1 year.

We found a low correlation between fear of movement scores at 4 weeks and physical health (σ = −0.25; p < 0.001) at 1 year (Table 3). These data indicate that a poor relationship exists between fear of movement and physical health and this was confirmed with analyses that controlled for potential confounders. There was no association between fear of movement scores at 4 weeks and physical health (β = 0.15; p = 0.34) at 1 year after adjusting for age, education, comorbid conditions, pain catastrophizing, depressive symptoms, and physical health at 4 weeks (Table 4).

A moderate relationship was found between depressive symptoms at 4 weeks and pain intensity (σ = 0.43; p < 0.001), pain interference (σ = 0.50; p < 0.001), and physical health (σ = −0.49; p < 0.001) at 1 year (Table 3). These moderate relationships were also noted in analyses that controlled for potential confounders. We found that patients with more depressive symptoms at 4 weeks had worse pain intensity (β = 0.49; p < 0.001), pain interference (β = 0.51; p < 0.001), and physical health (β = −0.32; p = 0.01) at 1 year compared with patients with less depressive symptoms after adjusting for age, education, pain catastrophizing, fear of movement, and pain or physical health at 4 weeks depending on the outcome of interest (Table 4). Results suggest that for every 10-point increase in depressive symptoms (range, 0–27) at 4 weeks, there was a 4.9-point and 5.1-point increase in pain intensity and pain interference (range, 0–10), respectively, and a 3.2-point decrease in physical health (range, 0–100) at 1 year.

Discussion

Psychosocial factors are important contributors to poor outcomes in chronic pain populations [24]. However, little is known about the relationship between specific psychosocial risk factors and long-term outcomes in patients after orthopaedic trauma. The current study aimed to determine whether pain catastrophizing, fear of movement, and depressive symptoms at 4 weeks after hospitalization were independent predictors of persistent pain and decreased physical health at 1 year after traumatic lower extremity injury. Results demonstrated a strong independent relationship between high pain catastrophizing scores and pain intensity and pain interference, whereas no relationship was found between high fear of movement scores and physical health at 1 year. A moderate independent relationship was found between depressive symptoms at 4 weeks and pain intensity, pain interference, and physical health at 1 year.

Several limitations of this study need to be considered when interpreting the results. First, caution should be exercised when generalizing results of this study to other trauma populations and settings outside of urban academic medical centers. A second limitation is that patient-reported measures were used to assess pain catastrophizing, fear of movement, and depressive symptoms instead of an interview with a mental health professional. We used well-accepted instruments that are reliable and valid; however, perceived psychological distress can innately influence and contribute to observed variances. Causation cannot be implied and additional psychosocial variables such as anxiety may yet explain some of the variance in outcomes after traumatic injury [12, 13, 66]. Finally, although responders (110 of 134) at 1 year were not statistically different from nonresponders (24 of 134) on baseline demographic and clinical variables, there is the potential for systematic differences based on unmeasured characteristics.

Our findings support a systematic review showing moderate evidence for the relationship between pain catastrophizing and postsurgical pain after musculoskeletal surgery [54]. Our results are also consistent with work by Vranceanu and colleagues [60] that found pain catastrophizing to be the sole predictor of pain at rest and pain during activity 5 to 8 months after skeletal trauma and controlling for depressive symptoms. In this study, pain catastrophizing demonstrated a stronger correlation and contributed a higher proportion of unique variance to pain intensity than depressive symptoms. Pain catastrophizing has generally been defined as the tendency to magnify pain symptoms and feelings of helplessness. Studies have consistently reported pain catastrophizing to be one of the most important predictors of persistent pain [19, 25, 52].

The hypothesis that fear of movement would have an independent relationship with physical health at 1 year was not supported. Results are unexpected given that the literature has reported on a strong association between fear of movement and physical disability in patients with various musculoskeletal pain populations such as low back pain, neck and shoulder pain, upper extremity conditions, and osteoarthritis [16, 20, 30, 48, 57]. Studies have even found pain-related fear to be a stronger predictor of physical disability than pain catastrophizing [31, 53]. With regard to orthopaedic surgery, several studies have demonstrated that high fear of movement is a predictor of increased disability and poor quality of life after lumbar spine surgery [5, 6, 36]. Additional research in the trauma population is needed to determine whether fear of movement is an important risk factor for patients with multiple injuries and higher injury severity.

We found a moderate association between depressive symptoms and increased pain at 1 year, which is consistent with several studies reporting on a depression-pain relationship in patients with traumatic injury [3, 10, 47]. Pain and psychological distress are interrelated and negative emotions tend to be elevated during the early postinjury period [3, 21, 37, 43, 66]. Thirty-eight percent of our patient population reported clinically significant depressive symptoms, which is consistent with other studies that have reported depression rates of 30% to 40% in the hospital and during the early postoperative period in patients with traumatic injury [3, 15, 45]. We also found a moderate relationship between depressive symptoms and decreased physical health at 1 year. Our finding supports work by Wegener et al. [63] who found that higher levels of negative mood contribute to poorer physical function during the first year of recovery after lower extremity trauma.

This study adds to a growing body of literature suggesting that early identification of psychosocial risk factors is needed to identify patients at high risk for poor outcomes after traumatic injury [3, 11, 12, 60, 66]. In particular, our findings contribute to research on the importance of pain catastrophizing and depressive symptoms to persistent postsurgical pain and physical disability. Cognitive and behavioral strategies that target pain catastrophizing and psychological distress have proven effective for chronic and surgical pain populations and may be beneficial for trauma survivors [4, 9, 26, 32, 55, 59, 64]. More specifically, cognitive-restructuring strategies such as identifying automatic negative thoughts, constructing realistic alternative responses, and acquiring positive coping self-statements may be beneficial for pain catastrophizing, whereas relaxation such as breathing and progressive muscle relaxation and mindfulness training can be useful techniques to address depression [24]. A pilot randomized controlled trial of a mind-body skills-based intervention, focusing on relaxation strategies, problem-solving, and cognitive restructuring, found that a biopsychosocial approach to rehabilitation was feasible, acceptable, and potentially efficacious in patients with acute orthopaedic trauma [61]. Additional research is needed to determine the large-scale effects of cognitive-behavioral-based interventions in patients at risk for poor outcomes after traumatic injury.

References

Airey CM, Chell SM, Rigby AS, Tennant A, Connelly JB. The epidemiology of disability and occupation handicap resulting from major traumatic injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2001;23:509–515.

Archer KR, Abraham CM, Song Y, Obremskey WT. Cognitive-behavioral determinants of pain and disability two years after traumatic injury: a cross-sectional survey study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72:473–479.

Archer KR, Castillo RC, Wegener ST, Abraham CM, Obremskey WT. Pain and satisfaction in hospitalized trauma patients: the importance of self-efficacy and psychological distress. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72:1068–1077.

Archer KR, Motzny N, Abraham CM, Yaffe D, Seebach CL, Devin CJ, Spengler DM, McGirt MJ, Aaronson OS, Cheng JS, Wegener ST. Cognitive-behavioral-based physical therapy to improve surgical spine outcomes: a case series. Phys Ther. 2013;93:1130–1139.

Archer KR, Seebach CL, Mathis S, Riley LH, Wegener ST. Early postoperative fear of movement predicts pain, disability, and physical health 6 months after spinal surgery for degenerative conditions. Spine J. 2014;14:759–767.

Archer KR, Wegener ST, Seebach C, Song Y, Skolasky RS, Thornton C, Khanna AJ, Riley LH. The effect of fear of movement beliefs on pain and disability after surgery for lumbar and cervical degenerative conditions. Spine. 2011;36:1554–1562.

Bosse MJ, MacKenzie EJ, Kellam JF, Burgess AR, Webb LX, Swiontkowski MF, Sanders RW, Jones AL, McAndrew MP, Patterson BM, McCarthy ML, Travison TG, Castillo RC. An analysis of outcomes of reconstruction or amputation after leg-threatening injuries. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1924–1931.

Burwinkle T, Robinson JP, Turk DC. Fear of movement: factor structure of the Tampa scale of kinesiophobia in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. J Pain. 2005;6:384–391.

Butler AC, Chapman JE, Forman EM, Beck AT. The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26:17–31.

Castillo RC, MacKenzie EJ, Wegener ST, Bosse MJ; LEAP Study Group. Prevalence of chronic pain seven years following limb threatening lower extremity trauma. Pain. 2006;124:321–329.

Clay FJ, Newstead SV, Watson WL, Ozanne-Smith J, Guy J, McClure RJ. Bio-psychosocial determinants of persistent pain 6 months after non-life-threatening acute orthopaedic trauma. J Pain. 2010;11:420–430.

Clay FJ, Watson WL, Newstead SV, McClure RJ. A systematic review of early prognostic factors for persistent pain following acute orthopaedic trauma. Pain Res Manag. 2012;17:35–44.

Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23:129–138.

Cohen J, Cohen P, West S, Aiken L. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlational Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 3rd ed. Mahwah, NJ, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2003.

Crichlow RJ, Andres PL, Morrison SM, Haley SM, Vrahas MS. Depression in orthopaedic trauma patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1927–1933.

Das De S, Vranceanu AM, Ring DC. Contribution of kinesophobia and catastrophic thinking to upper-extremity-specific disability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:76–81.

French DJ, France CR, Vigneau F, French JA, Evans RT. Fear of movement/(re)injury in chronic pain: a psychometric assessment of the original English version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia. Pain. 2007;127:42–51.

George SZ, Calley D, Valencia C, Beneciuk JM. Clinical investigation of pain-related fear and pain catastrophizing for patients with low back pain. Clin J Pain. 2011;27:108–115.

Gopinath B, Jagnoor J, Nicholas M, Blyth F, Harris IA, Casey P, Cameron ID. Presence and predictors of persistent pain among persons who sustained an injury in a road traffic crash. Eur J Pain. 2014 Dec 8 [Epub ahead of print].

Grotle M, Vøllestad NK, Brox JI. Clinical course and impact of fear-avoidance beliefs in low back pain: prospective cohort study of acute and chronic low back pain: II. Spine. 2006;31:1038–1046.

Hinrichs-Rocker A, Schulz K, Järvinen I, Lefering R, Simanski C, Neugebauer EA. Psychosocial predictors and correlates for chronic post-surgical pain (CPSP)–a systematic review. Eur J Pain. 2009;13:719–730.

Holbrook TL, Anderson JP, Sieber WJ, Browner D, Hoyt DB. Outcome after major trauma: 12-month and 18-month follow-up results from the Trauma Recovery Project. J Trauma. 1999;46:765–773.

Jenkinson C, Layte R, Jenkinson D, Lawrence K, Petersen S, Paice C, Stradling J. A shorter form health survey: can the SF-12 replicate results from the SF-36 in longitudinal studies? J Public Health Med. 1997;19:179–186.

Jensen MP. Psychosocial approaches to pain management: an organizational framework. Pain. 2011;152:717–25.

Keefe FJ, Rumble ME, Scipio CD, Giordano LA, Perri LM. Psychological aspects of persistent pain: current state of the science. J Pain. 2004;5:195–211.

Kerns RD, Thorn BE, Dixon KE. Psychological treatments for persistent pain: an introduction. J Clin Psychol. 2006;62:1327–1331.

Khan RS, Ahmed K, Blakeway E, Skapinakis P, Nihoyannopoulos L, Macleod K, Sevdalis N, Ashrafian H, Platt M, Darzi A, Athanasiou T. Catastrophizing: a predictive factor for postoperative pain. Am J Surg. 2011;201:122–131.

Kori SH, Miller RP, Todd DD. Kinesiophobia: a new region of chronic pain behavior. Pain Management. 1990;3:35–43.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613.

Landers MR, Creger RV, Baker CV, Stutelberg KS. The use of fear-avoidance beliefs and nonorganic signs in predicting prolonged disability in patients with neck pain. Man Ther. 2008;13:239–248.

Leeuw M, Goossens M, Linton SJ, Crombez G, Boersma K, Vlaeyen JW. The fear-avoidance model of musculoskeletal pain: current state of scientific evidence. J Behav Med. 2007;30:77–94.

Linton SJ, Andersson T. Can chronic disability be prevented? A randomized trial of a cognitive behavioral intervention and two forms of information for patients with spinal pain. Spine. 2000;25:2825–2831.

Luo X, George ML, Kakouras I, Edwards CL, Pietrobon R, Richardson W, Hey L. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Short Form 12-Item Survey (SF-12) in patients with back pain. Spine. 2003;28:1739–1745.

MacKenzie EJ, Bosse MJ, Kellam JF, Pollak AN, Webb LX, Swiontkowski MF, Smith DG, Sanders RW, Jones AL, Starr AJ, McAndrew MP, Patterson BM, Burgess AR, Travison T, Castillo RC. Early predictors of long-term work disability after major limb trauma. J Trauma. 2006;61:688–694.

MacKenzie EJ, Bosse MJ, Pollak AN, Webb LX, Swiontkowski MF, Kellam JF, Smith DG, Sanders RW, Jones AL, Starr AJ, McAndrew MP, Patterson BM, Burgess AR, Castillo RC. Long-term persistence of disability following severe lower-limb trauma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1801–1809.

Mannion AF, Elfering A, Staerkle R, Junge A, Grob D, Dvorak J, Jacobshagen N, Semmer NK, Boos N. Predictors of multidimensional outcome after spinal surgery. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:777–786.

McCarthy ML, MacKenzie EJ, Edwin D Bosse MJ, Castillo RC, Starr A, LEAP study group. Psychological distress associated with severe lower-limb injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1689–1697.

Mendoza TR, Chen C, Brugger A, Hubbard R, Snabes M, Palmer SN, Zhang Q, Cleeland CS. The utility and validity of the modified Brief Pain Inventory in a multiple-dose postoperative analgesic trial. Clin J Pain. 2004;20:357–362.

Michaels AJ, Michaels CE, Smith JS, Moon CH, Peterson C, Long WB. Outcome from injury: general health, work status, and satisfaction at 12 months after trauma. J Trauma. 2000;48:841–850.

Myers R. Classical and Modern Regression With Applications. 2nd ed. Boston, MA, USA: Duxbury; 1990.

Nederhand MJ, IJzerman MJ, Hermens HJ, Turk DC, Zilvold G. Predictive value of fear avoidance in developing clinical decision making. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:496–501.

Nota SP, Bot AG, Ring D, Kloen P. Disability and depression after orthopaedic trauma. Injury. 2015;46:207–212.

O’Donnell ML, Varker T, Holmes AC, Ellen S, Wade D, Creamer M, Silove D, McFarlane A, Bryant RA, Forbes D. Disability after injury: the cumulative burden of physical and mental health. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:e137–e143.

Osman A, Barrios F, Gutierrez PM, Kopper BA, Merrifield T, Grittmann L. The pain catastrophizing scale: further psychometric evaluation with adult samples. J Behav Med. 2000;23:351–365.

Ponsford J, Hill B, Karamitsios M, Bahar-Fuchs A. Factors influencing outcome after orthopaedic trauma. J Trauma. 2008;64:1001–1009.

Riddle DL, Wade JB, Jiranek WA, Kong X. Preoperative pain catastrophizing predicts pain outcome after knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:798–806.

Rivara FP, Mackenzie EJ, Jurkovich GJ, Nathens AB, Wang J, Scharfstein DO. Prevalence of pain in patients 1 year after major trauma. Arch Surg. 2008;143:282–287.

Somers TJ, Keefe FJ, Pells JJ, Dixon KE, Waters SJ, Riordan PA, Blumenthal JA, McKee DC, LaCaille L, Tucker JM, Schmitt D, Caldwell DS, Kraus VB, Sims EL, Shelby RA, Rice JR. Pain catastrophizing and pain-related fear in osteoarthritis patients: relationships to pain and disability. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:863–872.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary care evaluation of mental disorders. Patient health questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744.

Sullivan M, Bishop S, Pivik J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7:524–532.

Sullivan M, Tanzer M, Stanish W, Fallaha M, Keefe FJ, Simmonds M, Dunbar M. Psychological determinants of problematic outcomes following total knee arthroplasty. Pain. 2009;143:123–129.

Sullivan M, Thorn B, Rodgers W, Ward LC. Path model of psychological antecedents to pain experience. Clin J Pain. 2004;20:164–173.

Swinkels-Meewisse IE, Roelofs J, Oostendorp RA, Verbeek AL, Vlaeyen JW. Acute low back pain: pain-related fear and pain catastrophizing influence physical performance and perceived disability. Pain. 2006;120:36–43.

Theunissen M, Peters ML, Bruce J, Gramke H, Marcus MA. Preoperative anxiety and catastrophizing. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association with chronic postsurgical pain. Clin J Pain. 2012;28:819–841.

Turner JA, Maci L, Aaron LA. Short- and long-term efficacy of brief cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with chronic temporomandibular disorder pain: a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2006;121:181–194.

Vlaeyen JW, Kole-Snijders AM, Boeren RG, van Eek H. Fear of movement/(re)injury in chronic low back pain and its relation to behavioral performance. Pain. 1995;62:363–372.

Vlaeyen JW, Linton SJ. Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. Pain. 2000;85:317–332.

Vles WJ, Steyerberg EW, Seeink-Bot M, van Beeck EF, Meeuwis JD, Leenen LP. Prevalence and determinants of disabilities and return to work after trauma. J Trauma. 2005;58:126–135.

Von Korff M, Balderson BH, Saunders K, Miglioretti DL, Lin EH, Berry S, Moore JE, Turner JA. A trial of an activating intervention for chronic back pain in primary care and physical therapy settings. Pain. 2005;113:323–330.

Vranceanu AM, Bachoura A, Weening A, Vrahas M, Smith RM, Ring D. Psychological factors predict disability and pain intensity after skeletal trauma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:e20.

Vranceanu AM, Hageman M, Strooker J, Ter Meulen D, Vrahas M, Ring D. A preliminary RCT of a mind body skills based intervention addressing mood and coping strategies in patients with acute orthopaedic trauma. Injury. 2015;46:552–557.

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller DS. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–223.

Wegener ST, Castillo RC, Haythornthwaite J, Mackenzie EJ, Bosse MJ; LEAP Study Group. Psychological distress mediates the effect of pain on function. Pain. 2011;152:1349–1357.

Williams DA, Cary M, Groner K, Chaplin W, Glazer L, Rodriguez A, Clauw D. Improving physical functional status in patients with fibromyalgia: a brief cognitive-behavioral intervention. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:1280–1286.

Williamson OD, Epi GD, Gabbe BJ, Physio B, Cameron PA, Edwards ER, Richardson MD; Victorian Orthopaedic Trauma Outcome Registry Project Group. Predictors of moderate or severe pain 6 months after orthopaedic injury: a prospective cohort study. J Orthop Trauma. 2009;23:139–144.

Wood R, Maclean L, Pallister I. Psychological factors contributing to perceptions pain intensity after acute orthopaedic injury. Injury. 2011;42:1214–1218.

Zalon ML. Comparison of pain measures in surgical patients. J Nurs Meas. 1999;7:135–152.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no funding or commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research ® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

About this article

Cite this article

Archer, K.R., Abraham, C.M. & Obremskey, W.T. Psychosocial Factors Predict Pain and Physical Health After Lower Extremity Trauma. Clin Orthop Relat Res 473, 3519–3526 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-015-4504-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-015-4504-6