Abstract

Purpose of review

Doxorubicin has long been known to cause cardiotoxicity, yet our understanding of its pathophysiologic mechanisms remains incomplete. This review aims to update readers on the most recent evidence supporting candidate mechanisms and proposed treatments for doxorubicin cardiotoxicity.

Recent findings

Doxorubicin causes cardiotoxicity via traditional mechanisms, such as oxidative stress, DNA and mitochondrial damage, and iron overload, as well as through novel pathways such as autophagy and CYP1 induction. The relative importance of each pathway and how these pathways interact with each other is not well-understood. Novel approaches to cardioprotection are needed.

Summary

Novel mechanisms of doxorubicin cardiotoxicity represent exciting opportunities for prevention and treatment of this entity. Further studies are needed to translate recent findings into clinical use.

Similar content being viewed by others

References and recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

• Cardinale D, Colombo A, Bacchiani G, et al. Early detection of anthracycline cardiotoxicity and improvement with heart failure therapy. Circulation. 2015;131(22):1981–8. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013777. This is a study of the change in LVEF in a cohort of 2625 patients receiving chemotherapy with anthrayclines. Cardiotoxicity developed at a mean of 3.5 months after completion of chemotherapy, and 98% of cardiotoxicity was seen within the first year.

von Hoff DD, Layard MW, Basa P, Davis HL Jr, von Hoff A, Rozencweig M, et al. Risk factors for doxorubicin-induced congestive heart failure. Ann Intern Med. 1979;91(5):710–7. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-91-5-710.

Zamorano JL, Lancellotti P, Rodriguez Muñoz D, Aboyans V, Asteggiano R, Galderisi M, et al. 2016 ESC Position Paper on cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity developed under the auspices of the ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines: The Task Force for cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19(1):9–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.654.

Reichardt P, Tabone M-D, Mora J, Morland B, Jones RL. Risk–benefit of dexrazoxane for preventing anthracycline-related cardiotoxicity: re-evaluating the European labeling. Future Oncol. 2018;14(25):2663–76. https://doi.org/10.2217/fon-2018-0210.

Saleme B, Gurtu V, Zhang Y, et al. Tissue-specific regulation of p53 by PKM2 is redox dependent and provides a therapeutic target for anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11(478):eaau8866. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aau8866.

•• Amgalan D, Garner TP, Pekson R, et al. A small-molecule allosteric inhibitor of BAX protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. Nat Can. 2020;1(3):315–28. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43018-020-0039-1. This study identified a small-molecule BAX inhibitor that prevents apoptosis and necrosis when given with doxorubicin in zebrafish and mice, preventing the development of cardiotoxicity without compromising its anticancer efficacy.

A Phase 1/2 Study of INCB001158 in combination with chemotherapy in subjects with solid tumors. Clinicaltrials.Gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT03314935. Published 2019.

• Finkelman BS, Putt M, Wang T, et al. Arginine-nitric oxide metabolites and cardiac dysfunction in patients with breast cancer. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(2):152–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.019. This study of 170 patients with breast cancer undergoing treatment with doxorubicin with or without trastuzumab found that early alterations in arginine-nitric oxide metabolite levels were associated with an increased risk of cardiac dysfunction.

Jay SM, Murthy AC, Hawkins JF, Wortzel JR, Steinhauser ML, Alvarez LM, et al. An engineered bivalent neuregulin protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity with reduced proneoplastic potential. Circulation. 2013;128(2):152–61. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002203.

Rodon J, Dienstmann R, Serra V, Tabernero J. Development of PI3K inhibitors: lessons learned from early clinical trials. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10(3):143–53. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.10.

Liu Y, Asnani A, Zou L, et al. Visnagin protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy through modulation of mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(266):266ra170–0. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3010189.

• Asnani A, Zheng B, Liu Y, et al. Highly potent visnagin derivatives inhibit Cyp1 and prevent doxorubicin cardiotoxicity. JCI insight. 2018;3(1). https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.96753. This study examined derivatives of the CYP1 inhibitor visnagin and identified derivatives that were highly potent and prevented CYP1 induction and cardiomyopathy after doxorubicin in animal models, suggestive that small molecule CYP1 inhibitors could provide clinical benefit.

Doroshow JH. Effect of anthracycline antibiotics on oxygen radical formation in rat heart. Cancer Res. 1983;43(2):460–72 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6293697.

Davies KJA, Doroshow JH. Redox cycling of anthracyclines by cardiac mitochondria. I. Anthracycline radical formation by NADH dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 1986;261(7):3060–7 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3456345.

Vásquez-Vivar J, Martasek P, Hogg N, Masters BSS, Pritchard KA, Kalyanaraman B. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase-dependent superoxide generation from adriamycin. Biochemistry. 1997;36(38):11293–7. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi971475e.

Berthiaume JM, Wallace KB. Adriamycin-induced oxidative mitochondrial cardiotoxicity. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2007;23(1):15–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10565-006-0140-y.

•• Ichikawa Y, Ghanefar M, Bayeva M, et al. Cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin is mediated through mitochondrial iron accumulation. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(2):617–30. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI72931. This study demonstrated that doxorubicin concentrates in the mitochondria of cardiomyocytes and increases mitochondrial iron and ROS levels. Dexrazoxane decreased mitochondrial iron levels and attenuated cardiac damage.

Myers CE, Gianni L, Simone CB, Klecker R, Greene R. Oxidative destruction of erythrocyte ghost membranes catalyzed by the doxorubicin-iron complex. Biochemistry. 1982;21(8):1707–13. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi00537a001.

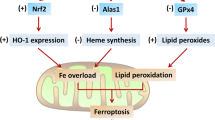

Fang X, Wang H, Han D, Xie E, Yang X, Wei J, et al. Ferroptosis as a target for protection against cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(7):2672–80. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1821022116.

Russo M, Guida F, Paparo L, Trinchese G, Aitoro R, Avagliano C, et al. The novel butyrate derivative phenylalanine-butyramide protects from doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21(4):519–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.1439.

Stockwell BR, Friedmann Angeli JP, Bayir H, Bush AI, Conrad M, Dixon SJ, et al. Ferroptosis: a regulated cell death Nexus linking metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell. 2017;171(2):273–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.021.

Conrad M, Angeli JPF, Vandenabeele P, Stockwell BR. Regulated necrosis: disease relevance and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15(5):348–66. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd.2015.6.

Yi LL, Kerrigan JE, Lin CP, et al. Topoisomerase IIβ-mediated DNA double-strand breaks: implications in doxorubicin cardiotoxicity and prevention by dexrazoxane. Cancer Res. 2007;67(18):8839–46. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1649.

Guo J, Guo Q, Fang H, Lei L, Zhang T, Zhao J, et al. Cardioprotection against doxorubicin by metallothionein is associated with preservation of mitochondrial biogenesis involving PGC-1α pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;737:117–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.05.017.

Jirkovský E, Popelová O, Křiváková-Staňková P, Vávrová A, Hroch M, Hašková P, et al. Chronic anthracycline cardiotoxicity: molecular and functional analysis with focus on nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 and mitochondrial biogenesis pathways. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;343(2):468–78. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.112.198358.

Hu X, Liu H, Wang Z, Hu Z, Li L. MiR-200a attenuated doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity through upregulation of Nrf2 in mice. Oxidative Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/1512326.

Zhao L, Qi Y, Xu L, Tao X, Han X, Yin L, et al. MicroRNA-140-5p aggravates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by promoting myocardial oxidative stress via targeting Nrf2 and Sirt2. Redox Biol. 2018;15:284–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2017.12.013.

Asnani A, Shi X, Farrell L, Lall R, Sebag IA, Plana JC, et al. Changes in citric acid cycle and nucleoside metabolism are associated with anthracycline cardiotoxicity in patients with breast cancer. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2019;13:349–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12265-019-09897-y.

Gu J, Wang S, Guo H, Tan Y, Liang Y, Feng A, et al. Inhibition of p53 prevents diabetic cardiomyopathy by preventing early-stage apoptosis and cell senescence, reduced glycolysis, and impaired angiogenesis article. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(2):82. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-017-0093-5.

Li J, Wang PY, Long NA, Zhuang J, Springer DA, Zou J, et al. P53 prevents doxorubicin cardiotoxicity independently of its prototypical tumor suppressor activities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(39):19626–34. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1904979116.

Nebigil CG, Désaubry L. Updates in anthracycline-mediated cardiotoxicity. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9(NOV). https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2018.01262

Vedam K, Nishijima Y, Druhan LJ, Khan M, Moldovan NI, Zweier JL, et al. Role of heat shock factor-1 activation in the doxorubicin-induced heart failure in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298(6):H1832–41. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.01047.2009.

Kalivendi SV, Kotamraju S, Zhao H, Joseph J, Kalyanaraman B. Doxorubicin-induced apoptosis is associated with increased transcription of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase: effect of antiapoptotic antioxidants and calcium. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(50):47266–76. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M106829200.

Neilan TG, Blake SL, Ichinose F, Raher MJ, Buys ES, Jassal DS, et al. Disruption of nitric oxide synthase 3 protects against the cardiac injury, dysfunction, and mortality induced by doxorubicin. Circulation. 2007;116(5):506–14. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.652339.

Cardounel AJ, Xia Y, Zweier JL. Endogenous methylarginines modulate superoxide as well as nitric oxide generation from neuronal nitric-oxide synthase: differences in the effects of monomethyl- and dimethylarginines in the presence and absence of tetrahydrobiopterin. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(9):7540–9. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M410241200.

Lin KY, Ito A, Asagami T, Tsao PS, Adimoolam S, Kimoto M, et al. Impaired nitric oxide synthase pathway in diabetes mellitus: role of asymmetric dimethylarginine and dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase. Circulation. 2002;106(8):987–92. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000027109.14149.67.

Toya T, Hakuno D, Shiraishi Y, Kujiraoka T, Adachi T. Arginase inhibition augments nitric oxide production and facilitates left ventricular systolic function in doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy in mice. Phys Rep. 2014;2(9):e12130. https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.12130.

Nitiss JL. Targeting DNA topoisomerase II in cancer chemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(5):338–50. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc2607.

Capranico G, Tinelli S, Austin CA, Fisher ML, Zunino F. Different patterns of gene expression of topoisomerase II isoforms in differentiated tissues during murine development. BBA - Gene Struct Expr. 1992;1132(1):43–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-4781(92)90050-A.

Zhang S, Liu X, Bawa-Khalfe T, Lu LS, Lyu YL, Liu LF, et al. Identification of the molecular basis of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Nat Med. 2012;18(11):1639–42. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.2919.

Deng S, Yan T, Jendrny C, Nemecek A, Vincetic M, Gödtel-Armbrust U, et al. Dexrazoxane may prevent doxorubicin-induced DNA damage via depleting both topoisomerase II isoforms. BMC Cancer. 2014;14(1):842. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-842.

Yarden Y, Sliwkowski MX. Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2(2):127–37. https://doi.org/10.1038/35052073.

Zhao YY, Sawyer DR, Baliga RR, Opel DJ, Han X, Marchionni MA, et al. Neuregulins promote survival and growth of cardiac myocytes: persistence of ErbB2 and ErbB4 expression in neonatal and adult ventricular myocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(17):10261–9. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.273.17.10261.

Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, Fuchs H, Paton V, Bajamonde A, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against her2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(11):783–92. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200103153441101.

Belmonte F, Das S, Sysa-Shah P, Sivakumaran V, Stanley B, Guo X, et al. ErbB2 overexpression upregulates antioxidant enzymes, reduces basal levels of reactive oxygen species, and protects against doxorubicin cardiotoxicity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;309(8):H1271–80. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00517.2014.

Horie T, Ono K, Nishi H, Nagao K, Kinoshita M, Watanabe S, et al. Acute doxorubicin cardiotoxicity is associated with miR-146a-induced inhibition of the neuregulin-ErbB pathway. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;87(4):656–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvq148.

Fukazawa R, Miller TA, Kuramochi Y, Frantz S, Kim YD, Marchionni MA, et al. Neuregulin-1 protects ventricular myocytes from anthracycline-induced apoptosis via erbB4-dependent activation of PI3-kinase/Akt. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35(12):1473–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2003.09.012.

Li Q, Ahmed S, Loeb JA. Development of an autocrine neuregulin signaling loop with malignant transformation of human breast epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64(19):7078–85. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1152.

Hsieh SY, He JR, Hsu CY, Chen WJ, Bera R, Lin KY, et al. Neuregulin/erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog 3 autocrine loop contributes to invasion and early recurrence of human hepatoma. Hepatology. 2011;53(2):504–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.24083.

Chen Y, Azad MB, Gibson SB. Superoxide is the major reactive oxygen species regulating autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16(7):1040–52. https://doi.org/10.1038/cdd.2009.49.

•• Li DL, Wang ZV, Ding G, et al. Doxorubicin blocks cardiomyocyte autophagic flux by inhibiting lysosome acidification. Circulation. 2016;133(17):1668–87. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017443. This study assessed the effects of doxorubicin exposure on autophagy and found that exposure inhibited autophagic flux. Reduced expression of autophagy-related protein Beclin 1 resulted in normalization of autophagy and prevention of cardiotoxicity in mice.

Xu X, Bucala R, Ren J. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor deficiency augments doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(6). https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.113.000439.

Kawaguchi T, Takemura G, Kanamori H, Takeyama T, Watanabe T, Morishita K, et al. Prior starvation mitigates acute doxorubicin cardiotoxicity through restoration of autophagy in affected cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;96(3):456–65. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvs282.

•• Li M, Sala V, De Santis MC, et al. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma inhibition protects from anthracycline cardiotoxicity and reduces tumor growth. Circulation. 2018;138(7):696–711. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030352. This study demonstrated that blockade of PI3Kγ in mice prevented doxorubicin cardiotixicity.

Smolensky D, Rathore K, Bourn J, Cekanova M. Inhibition of the PI3K/AKT pathway sensitizes oral squamous cell carcinoma cells to anthracycline-based chemotherapy in vitro. J Cell Biochem. 2017;118(9):2615–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.25747.

Jordan JH, Castellino SM, Meléndez GC, et al. Left ventricular mass change after anthracycline chemotherapy. Circ Hear Fail. 2018;11(7). https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.117.004560

Maejima Y, Usui S, Zhai P, Takamura M, Kaneko S, Zablocki D, et al. Muscle-specific RING finger 1 negatively regulates pathological cardiac hypertrophy through downregulation of calcineurin A. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7(3):479–90. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000713.

Willis MS, Parry TL, Brown DI, et al. Doxorubicin exposure causes subacute cardiac atrophy dependent on the striated muscle-specific ubiquitin ligase MuRF1. Circ Heart Fail. 2019;12(3). https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.118.005234.

Lubieniecka JM, Graham J, Heffner D, et al. A discovery study of daunorubicin induced cardiotoxicity in a sample of acute myeloid leukemia patients prioritizes P450 oxidoreductase polymorphisms as a potential risk factor. Front Genet. 2013;4(NOV). https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2013.00231

Wells QS, Veatch OJ, Fessel JP, Joon AY, Levinson RT, Mosley JD, et al. Genome-wide association and pathway analysis of left ventricular function after anthracycline exposure in adults. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2017;27(7):247–54. https://doi.org/10.1097/FPC.0000000000000284.

Zordoky BNM, Anwar-Mohamed A, Aboutabl ME, El-Kadi AOS. Acute doxorubicin cardiotoxicity alters cardiac cytochrome P450 expression and arachidonic acid metabolism in rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2010;242(1):38–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2009.09.012.

Lam PY, Kutchukian P, Anand R, et al. Cyp1 inhibition prevents doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy in a zebrafish heart-failure model. Chem Bio Chem. 2020:cbic.201900741. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbic.201900741

Volkova M, Palmeri M, Russell KS, Russell RR. Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor by doxorubicin mediates cytoprotective effects in the heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;90(2):305–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvr007.

Wei H, Bedja D, Koitabashi N, Xing D, Chen J, Fox-Talbot K, et al. Endothelial expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 protects the murine heart and aorta from pressure overload by suppression of TGF-β signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(14):E841–50. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1202081109.

Lee KA, Qian DZ, Rey S, Wei H, Liu JO, Semenza GL. Anthracycline chemotherapy inhibits HIF-1 transcriptional activity and tumor-induced mobilization of circulating angiogenic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(7):2353–8. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0812801106.

Tanaka T, Yamaguchis J, Shojis K, Nangakus M. Anthracycline inhibits recruitment of hypoxia-inducible transcription factors and suppresses tumor cell migration and cardiac angiogenic response in the host. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(42):34866–82. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M112.374587.

Curigliano G, Lenihan D, Fradley M, Ganatra S, Barac A, Blaes A, et al. Management of cardiac disease in cancer patients throughout oncological treatment: ESMO consensus recommendations. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(2):171–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2019.10.023.

Liesse K, Harris J, Chan M, Schmidt ML, Chiu B. Dexrazoxane significantly reduces anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity in pediatric solid tumor patients. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2018;40(6):417–25. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0000000000001118.

Shapira J, Gotfried M, Lishner M, Ravid M. Reduced cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin by a 6-hour infusion regimen. A prospective randomized evaluation. Cancer. 1990;65(4):870–3. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19900215)65:4<870::AID-CNCR2820650407>3.0.CO;2-D.

LEGHA SS. Reduction of doxorubicin cardiotoxicity by prolonged continuous intravenous infusion. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96(2):133–9. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-96-2-133.

Van Dalen EC, Van Der Pal HJH, Caron HN, Kremer LCM. Different dosage schedules for reducing cardiotoxicity in cancer patients receiving anthracycline chemotherapy. In: van Dalen EC, ed. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2009. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005008.pub3.

Feijen EAM, Leisenring WM, Stratton KL, Ness KK, van der Pal HJH, van Dalen EC, et al. Derivation of anthracycline and anthraquinone equivalence ratios to doxorubicin for late-onset cardiotoxicity. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(6):864–71. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.6634.

Green AE, Rose PG. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in ovarian cancer. Int J Nanomedicine. 2006;1(3):229–39 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17717964.

Smith LA, Cornelius VR, Plummer CJ, Levitt G, Verrill M, Canney P, et al. Cardiotoxicity of anthracycline agents for the treatment of cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMC Cancer. 2010;10(1):337. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-10-337.

Uziely B, Jeffers S, Isacson R, Kutsch K, Wei-Tsao D, Yehoshua Z, et al. Liposomal doxorubicin: antitumor activity and unique toxicities during two complementary phase I studies. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(7):1777–85. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1995.13.7.1777.

Hasinoff BB, Patel D, Wu X. The oral iron chelator ICL670A (deferasirox) does not protect myocytes against doxorubicin. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;35(11):1469–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2003.08.005.

McGowan JV, Chung R, Maulik A, Piotrowska I, Walker JM, Yellon DM. Anthracycline chemotherapy and cardiotoxicity. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2017;31(1):63–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10557-016-6711-0.

Tebbi CK, London WB, Friedman D, Villaluna D, de Alarcon PA, Constine LS, et al. Dexrazoxane-associated risk for acute myeloid leukemia/myelodysplastic syndrome and other secondary malignancies in pediatric Hodgkin’s disease. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(5):493–500. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.02.3879.

ZINECARD (dexrazoxane) for injection. accessdata.fda.gov. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/020212s017lbl.pdf. Published 2014.

Swain SM, Whaley FS, Gerber MC, Weisberg S, York M, Spicer D, et al. Cardioprotection with dexrazoxane for doxorubicin-containing therapy in advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(4):1318–32. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1997.15.4.1318.

Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128(16):e240–327. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8776.

Vaynblat M, Shah HR, Bhaskaran D, Ramdev G, Davis WJ III, Cunningham JN Jr, et al. Simultaneous angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition moderates ventricular dysfunction caused by doxorubicin. Eur J Heart Fail. 2002;4(5):583–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1388-9842(02)00091-0.

Boucek RJ, Steele A, Miracle A, Atkinson J. Effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor on delayed-onset doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2003;3(4):319–29. https://doi.org/10.1385/CT:3:4:319.

Gupta V, Kumar Singh S, Agrawal V, Bali ST. Role of ACE inhibitors in anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(11):e27308. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.27308.

Janbabai G, Nabati M, Faghihinia M, Azizi S, Borhani S, Yazdani J. Effect of enalapril on preventing anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2017;17(2):130–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12012-016-9365-z.

Gujral DM, Lloyd G, Bhattacharyya S. Effect of prophylactic betablocker or ACE inhibitor on cardiac dysfunction & heart failure during anthracycline chemotherapy ± trastuzumab. Breast. 2018;37:64–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2017.10.010.

Kalay N, Basar E, Ozdogru I, Er O, Cetinkaya Y, Dogan A, et al. Protective effects of carvedilol against anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(11):2258–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.052.

Nabati M, Janbabai G, Baghyari S, Esmaili K, Yazdani J. Cardioprotective effects of carvedilol in inhibiting doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2017;69(5):279–85. https://doi.org/10.1097/FJC.0000000000000470.

Avila MS, Ayub-Ferreira SM, de Barros Wanderley MR, et al. Carvedilol for prevention of chemotherapy-related cardiotoxicity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(20):2281–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.049.

Huang S, Zhao Q, Yang Z, Diao KY, He Y, Shi K, et al. Protective role of beta-blockers in chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity—a systematic review and meta-analysis of carvedilol. Heart Fail Rev. 2019;24(3):325–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-018-9755-3.

Bosch X, Rovira M, Sitges M, Domènech A, Ortiz-Pérez JT, de Caralt TM, Morales-Ruiz M, Perea RJ, Monzó M, Esteve J Enalapril and carvedilol for preventing chemotherapy-induced left ventricular systolic dysfunction in patients with malignant hemopathies: the OVERCOME trial (prevention of left ventricular dysfunction with enalapril and caRvedilol in patients submitted t. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61(23):2355–2362. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.02.072.

Gulati G, Heck SL, Røsjø H, et al. Neurohormonal blockade and circulating cardiovascular biomarkers during anthracycline therapy in breast cancer patients: results from the PRADA (Prevention of Cardiac Dysfunction During Adjuvant Breast Cancer Therapy) Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(11). https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.117.006513.

Akpek M, Ozdogru I, Sahin O, Inanc M, Dogan A, Yazici C, et al. Protective effects of spironolactone against anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17(1):81–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.196.

Burridge PW, Li YF, Matsa E, Wu H, Ong SG, Sharma A, et al. Human induced pluripotent stem cell–derived cardiomyocytes recapitulate the predilection of breast cancer patients to doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Nat Med. 2016;22(5):547–56. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.4087.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Christopher W. Hoeger, Cole Turissini, and Aarti Asnani declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Cardio-Oncology

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hoeger, C.W., Turissini, C. & Asnani, A. Doxorubicin Cardiotoxicity: Pathophysiology Updates. Curr Treat Options Cardio Med 22, 52 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11936-020-00842-w

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11936-020-00842-w