Abstract

Purpose of the Review

Smart sex toys (‘teledildonics’), are digitally enabled haptic devices designed for sexual or erotic stimulation. Devices may conform to conventional sex toy design (e.g. dildoes) or take other forms. Their primary purpose is to provide sexual or erotic stimulation through the networked haptic function. Here, we present a narrative review of academic work in which we aimed to synthesise current lines of inquiry relating to cultural impacts and research on risks and benefits.

Recent Findings.

Forty-one articles were included, published between 2011 and 2024. The articles focused on: prevalence and context of smart sex use; considerations on whether smart sex toys have potential to disrupt normative gendered sexual scripts; whether smart sex toys have potential to expand or change people’s expectations for sex; the potential for harm and non-consensual use; the politics of data security; and the possibilities for smart sex toys to enhance sexual wellbeing.

Summary

Smart sex toys may create new ways for people to explore sexual connection and experience, including people with limited mobility. Data security and consensual use should be considered in product development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

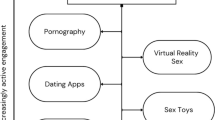

Digitally enhanced devices are ubiquitous in modern life (the ‘internet-of-things’) and are increasingly making their way into people’s sex lives via an expanding market in smart sex toys, also referred to as teledildonics or digitally enabled sex devices. The concept of teledildonics is not new, in fact most writers trace its origin to a 1991 text by Howard Rheingold, whose writings aimed to encourage people’s imagination about the possibilities for new technology to simulate or augment human sensory experience. Rheingold’s definition of teledildonics referred to machines which enable the physiological sensation of sexual pleasure to be communicated and felt by people, in real time, across distances [1]. While the current reality of teledildonic technology has not generated a radical re-imagining of human–machine sexual interaction, the possibilities for what it could become, and the ethical implications of this, have generated careful consideration in academic literature.

Teledildonics refers to digitally enabled devices (or smart products) designed for sexual or erotic stimulation. The currently available range of teledildonic products extends far beyond the ‘dildo’ implied in teledildonics, making the term ‘smart sex toys’ a more accurate representation of these products. As well as toys shaped as dildoes and sleeves (for penises), smart sex toys include products for clitoral stimulation and other haptic devices (e.g. jewellery or other wearable products) designed to provide erotic stimulation [2,3,4,5] or simulate kissing [4,5,6,7]. Smart sex toys are connected, usually via Bluetooth, to a smart-phone or tablet and controlled through an app, which often also collects data communicated from the device, such as body temperature and usage patterns [8].

Smart sex toys are marketed as products that enable ‘sex at a distance’ as the person controlling the device may be located some distance from the user/wearer. Some product apps also include video functions to facilitate visual connection [9], while others enable mutual connectivity, so two users can concurrently control each other’s device [4]. In addition, although this technology is still emerging, some products are designed to communicate physical sensation through the devices. For example, a person’s vaginal contractions may be communicated, via the app, to a sheath or ‘sleeve’ worn by their partner, which contracts accordingly [10].

The sex and technology (sextech) industry within which these products are currently being developed is diverse. It includes a handful of major companies, such as Lovense®, We-Vibe®, and Kiiroo®, which produce the leading (or most high profile) smart sex toys. These are predominantly marketed to heterosexual couples and include a range of networked dildos/vibrators and sleeves [4, 10, 11]. Alongside this, however, the sextech industry is defined by a range of smaller tech start-ups, many of which are female-led or queer-oriented and seek to support a culture of sex positivity, rejecting sexual moralism [12,13,14]. Interest in sextech was heightened as a result of Covid-19-related social lockdowns in 2020–2021 in which there was a sharp increase in reliance on technology for human connection [15].

As smart sex toys are relatively new, there is only a limited body of academic work which has looked closely at its use or implications. Here we present a review of the extant literature on these technologies with the aim of identifying current thinking regarding the possible impact on sexual experience, sexual cultures, ethical or safety concerns, and potential health implications or benefits.

Method

For this review, we used the checklist of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA- ScR) as a guideline for ensuring rigour in our method [16]. However, given our aim was to scope current foci of academic interest on the topic, rather than to synthesise findings from a body of evidence, we followed the conventions of a critical narrative synthesis [17].

Search Strategy

A literature search was conducted on Google Scholar and a combined database that incorporated PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and JSTOR. The search terms we used were: “teledildonic/s”, “smart sex + toy/device”, “digital sex + toy/device”, “networked sex”, “haptic technology and sex”, “haptic sex”, “wireless sex + toy/device”, “disability and teledildonic”, “disability and haptic”, “kissing machines”, “kissing and technology”. As we read each article, we systematically checked the reference lists to identify articles we had missed.

Criteria

While there are a range of sextech products designed for sexual pleasure (e.g. sex robots, virtual reality pornography), the definition of smart sex toys used for this review was digitally networked, haptic devices primarily designed for sexual or erotic pleasure. Such devices may conform to the design of conventional sex toys (e.g. dildos) or take other forms, but in all cases they are a physical device primarily designed to provide sexual or erotic stimulation through the haptic function.

Given the relative newness of this technology, we did not impose restrictions on date of publication. Our inclusion criteria specified that articles must engage in extended discussion about smart sex toys even if this was not the focus of the article (e.g. articles on virtual reality porn that discuss smart sex toys). We included commentaries or essays published in academic or industry journals, empirical papers presenting original research, and review papers.

Data Synthesis

Our analytical method involved careful reading of each article, attending to the disciplinary focus and methods as well as key insights generated (see Table 1). These findings were then used to identify salient issues, key debates and lines of inquiry as well as current evidence of health benefits.

Findings

Our review included 41 articles (Table 1) published between 2011 and 2024 (note, we excluded Rheingold’s 1991 text as it did not relate to technology current available). Reflective of the newness of smart sex toys, most articles are theoretical considerations of the potential implications of these technologies for gendered sexual interactions, embodied sexual experiences or for health and wellbeing. Below we outline key themes identified across this body of work including: existing work on prevalence and context of smart sex use; considerations on whether the unique qualities of smart sex toys have potential to disrupt normative gendered sexual scripts; considerations on whether smart sex toys have potential to expand or change people’s expectations for, or experiences of, sex; the potential for harm and non-consensual use of smart sex toys; the politics of data security in relation to smart sex toys; and the possibilities for smart sex toys to enhance sexual wellbeing.

Frequency, Patterns and Context of Use

To our knowledge, there are no existing population-based studies which explore prevalence of smart sex toy use. However, in a recent survey of 7512 US adults, nine percent reported some experience with smart sex toys. Usage was more common among men, compared to women, and lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) people compared to heterosexual people [26].

There is a small body of research exploring user experiences [5, 6, 35, 38, 42]. This is generally focused on the use and impact in couple relationships. In a small study of long-distance couples, Steensig and Westh [38] found couples tended to use the We-Vibe device when physically together rather than for sex at a distance, and they saw limited value for it beyond that of conventional sex toys. Similarly, Watson et al. [42] found the perceived benefits of the We-Vibe related to enhancement of couple intimacy and female pleasure, rather than for long-distance sex. Cheok and Zhang [6], however, in their study of the ‘Kissinger’, a haptic mobile phone attachment that allows users to feel lip pressure (simulated kissing) from a connected user, found daily use of the Kissinger increased relationship satisfaction for couples in a long-distance relationship.

The use of smart sex toys for sex at a distance seems most established in the webcam industry, with platforms such as Chaturbate allowing paying audience members to control devices worn by webcam performers [27, 34]. There is limited research, however, on user experience of this (either performers or customers).

Smart Sex Toys as Disruptive Technology?

A central question that underpinning academic work in this field, across multiple disciplines (design, humanities, law), is whether smart sex toys have potential to disrupt or expand heteronormative and gendered sexual scripts by centring female pleasure or encouraging users to creatively explore sexual pleasure. Optimism for change is focused on the emergent sex-positive, feminist and queer cultures within sextech start-up businesses [47] and the overt focus in the sextech industry on marketing to women [48], which have potential to generate a market in female centred or ‘queer’ products. However, perspectives on this vary and many authors note that hetero and cisgender normative attitudes tend to dominate the mainstream commercial market in smart sex toys [12, 20, 23, 43]. Faustino [25], for example, argues that the design of major smart sex toy products (dildos for women and sleeves for men) recreates normative penis/vagina intercourse. The design, along with marketing of these products as being just like ‘real’ sex, does little to expand normative sexual scripts or foster alternative pleasure seeking, including clitoral stimulation. Kaisar [10] is more optimistic, recognising the centrality of coitus in the design of many smart sex toys, but also arguing they do more than just simulate of intercourse. Rather, Kaiser sees smart sex toy use as akin to mutual masturbation that, when combined with non-human objects, datafication of sexual experience and distance from partner, offers potential for creative reimagining of sexual scripts [10].

Studies exploring the design and development of smart sex toys also tend to present an optimistic view of the potential for smart sex toys to creatively encourage pleasure [9, 12, 18,19,20]. Carpenter et al. (2018) present a series of designs for networked, haptic sex devices for non-binary bodies. These focus broadly on enabling pleasure across various regions of the body, rather than on simulating heterosexual intercourse – the point being that a ‘queer’ approach to smart sex toy design could enable a technology-facilitated expansion of people’s perspective on, and experience of, sexual pleasure.

In a study with 11 users of smart sex toys, Pym et al. [35] found that people’s experiences both reinforced and challenged heteronormative expectations of sex. Women found the devices created new opportunities for self-exploration and pleasure because the physical distance from their partner lessened their self-consciousness. Women explain that, as per normative feminine beauty standards, they often worried about looking unattractive during sex. They enjoyed that, with smart sex, they experienced freedom from this worry while also staying ‘present’ with their partner. Heterosexual men saw the devices as a medium to provide pleasure to their partner, a focus that challenged heteronormative conventions of male-centred pleasure but also reinforced notions of female pleasure as elusive and difficult.

Is Smart Sex ‘Real’ Sex?

Beyond (although not unrelated to) gendered sexual scripts, current academic work explores other cultural effects of smart sex toys, including the ways in which technologically mediated or enhanced sex may affect views on normative or ‘ordinary’ sexual practice. Liberati [31] argues that by introducing a world where sex with non-human objects is a readily available option, the experience of unmediated (in person) sex is changed because it becomes a choice for sexual pleasure, not an assumption. Similarly, Sparrow and Karas [36], in their discussion of the moral and legal dimensions of non-consensual use of smart sex toys, argue that widescale introduction and increasing sophistication of smart sex products will inevitably change what we consider to be ‘real’ sex. At present, it is likely that two people using networked sex toys would be seen to be engaging in mutual masturbation. However, as haptic technologies become more sophisticated, our perspective of what constitutes ‘real sex’ will also likely change. The potential for smart sex toys to recast conventional notions of ‘real’ bodies and ‘real’ sex, theoretically, offers radical potential for expanding what we consider possible, ‘real’ or ‘normal’, with regards to sex.

Extending this theme, some research considers the ways that smart sex toys, alongside other technologies that facilitate immersive sexual experiences with non-human objects (e.g. virtual reality), have potential to shift conventional ways of defining human bodies against non-human objects. By augmenting the human body, smart sex toys become, in effect, part of the human body, such that there is no clear separation between the human body (sensation and emotion) and non-human objects in networked sexual encounters [10, 22, 34]. Smart sex toys do not simply enable technologically mediated sexual interactions, they create sexual experiences that are defined, and determined, through collaboration between humans and technology [4]. Flore and Pienaar [11] further argue that the data produced by smart sex devices are part of this assemblage (which they term the sexuotechnical-assemblage). Data that is collected by devices and made available to users (e.g. to track physiological processes such as orgasm intensity) also shapes how people approach and experience networked sexual encounters.

Potential for Harm: Consent and Safety

While much of the literature on smart sex toys is optimistic about its potential for enhancing sexual pleasure and connection, concern about breaches of privacy and safety sits within this. Smart sex toys could enable sexual assault by deception in cases where a device is controlled by someone other than the person which the wearer/user of that device has consented to having control. This may occur as a result of a hacker taking control of the app, or the controlling app being given to another user without consent of both parties (e.g. a person handing their smart phone or app password to someone else) [8, 27, 36, 40, 44]. There are existing laws against rape by deception in some jurisdictions and people have been convicted of sexual assault for convincing a person to have sex with them by misrepresenting their intention (e.g. to pay) or misrepresenting their identity [36]. However, this is controversial territory, as Sparrow and Kraus [36] point out, given it can be hard to determine what level of deception should be considered criminal. For example, is it a criminal act to lie about one’s income to impress a potential lover? Sparrow and Kraus ask whether this ‘line’ is different in networked encounters where people may not be physically co-located. If a person misrepresents their gender, for example, in order to have sex with someone via smart sex toys, how much does this matter given the act does not involve physical contact? Gidaris [27] asks similar questions about the sexual rights of professional webcam performers. Would a professional webcam performer have rights to claim sexual assault if a second person was given access, without their knowledge, to the control of a device they were wearing/using? Döring et al. [21] argue that consideration of potential harm related to sextech needs to include reference to the commercial context of sexual interactions, including potential vulnerabilities and complexities arising from negotiating consent as part of a commercial exchange. To date, these questions have not been legally tested and, as networked sexual encounters can transcend jurisdictional boundaries, it may be a challenge to prosecute a case under criminal law [36].

A further consideration is whether manufacturers of smart sex products should be held accountable for sexual assault enacted with their products. Ley and Rambukkana [4] argue that responsibility for managing harm should sit with industry, not just the users, and a feminist ethics of consent should be built into the design of products. To explain this, they refer to examples from video gaming where processes for users to gain another person’s consent to interact or take actions are built into the game. With smart sex toys, there may be ways to integrate safe words or voice controls to enable user identification.

Data Security and Sexual Politics

Any internet enabled devices are vulnerable to hacking and non-consensual exposure of data. With smart sex toys, the likely impact of data breaches is public sexual shaming or extortion based on the threat of such shaming [39]. In 2017, sextech company We-Vibe settled a multi-million dollar lawsuit for failing to inform customers they were storing intimate user data such as body temperature, frequency and intensity of device use, in ways that could potentially be connected to user emails [37, 39]. While this did not result in a data breach, the existence of this store of data exposed the potential for a large amount of sensitive user information to be stolen. It also raised questions about what data is reasonable and ethical for manufacturers to collect and store. Albury et al. [13] argue that, in relation to the sextech industry, the right for users to have control over what data is collected and to assume safe storage of their data should be considered a sexual right. There are, of course, complex moral and political barriers to achieving such ‘data justice’ in a world where sexual pleasure is rarely valued as a human right. Sundén [39] similarly draws on the controversy over leaked user data from the networked toy company Lovense to theorise alternative ways to think about privacy in digitally networked contexts, one which priorities processes through which data security, consent and safety can be respectfully negotiated in public (or semi-public) spaces, rather than the ultimate regulatory goal being to ensure sexual pleasure is always kept hidden or private.

Smart Sex Toys as Wellness Products?

In the past decade, smart sex toys have increasingly found their way into an expanding market for sexual wellness products, in part due to the industry seeking to reach a mainstream audience and the rise of ‘sexual wellness’ markets [49, 50]. The ‘health-tech’ and ‘fem-tech’ industries, characterised by the rise of personal health tracking through smart devices, have concurrently been celebrated for enabling women greater insight and control over their health [51] and critiqued as a tool of neo-liberal governance, promoting forms of ‘self-optimisation’ (‘sexual optimisation’) and ‘healthism’ that place a burden of labour on individuals to enact ‘wellness’ in particular ways [32, 52]. Smart sex toys converge with ‘fem-tech’ at the point where these devices are used to both enable, and to monitor, sexual pleasure. Lupton [32] examines phone-based apps for self-monitoring sexual experiences, showing how they encourage normatively gendered ideas about sexual performance and the quantification of pleasure. The position of the user as both consumer and producer of this intimate data obfuscates the data tracking processes that occur, and potentially alienates users from their own embodied perceptions of pleasure [32]. Indeed, Flore and Pienaar [11] point to how ‘data-driven intimacy’, facilitated through smart sex products, bolsters a healthist discourse about ideal sexuality that ultimately places responsibility for any ‘failure’ of sexual wellness or sexual pleasure in the hands of users.

Other papers, however, show potential health benefits of data tracking via smart sex toys. Varod and Henti [41] found that data on sexual response may assist people who are struggling with erectile dysfunction or other sexual disorders as it provides individuals with insight into their sexual arousal patterns and responses. Further, Zhou et al. [46] found potential for smart sex devices to usefully inform sexual health research through collection of data that does not rely on self-report or the memory/recall of research participants.

Beyond data use, there is a small body of research exploring the potential for smart sex devices to facilitate sexual wellbeing. Marcotte et al. [33] show that smart sex toys may help with treating anxiety and depression by providing ‘self soothing’ and relaxation options. VR pornography with smart sex device capability has also been found to decrease sexual anxiety, with implications for its use in therapeutic practice [24].

Recent work on the development of smart sex toys for people with disabilities also points to how this technology works to mediate human touch and enhance sexual pleasure for people with limited mobility [20, 28]. Gomes and Wu [28] present a prototype of the neurodildo, a sex toy remotely controlled by brainwaves for people who have restricted functionality of their hands, arguing that networked sex toys will create new possibilities for partnered sexual connection for people with disability or restricted mobility. Similarly, Corti et al. [20] present a prototype idea for “Lovewear”, a wearable haptic device designed in collaboration with artists and people with disability to simulate human sexual touch through the device, targeting erogenous zones. These examples show the creative potential of new smart sex products to interact with human bodies in ways that not just simulate human sexual touch, but become part of it – an augmentation of the human body. In both articles, the authors highlight the inherent value of sexual pleasure and connection and the role that technology can play in facilitating this.

Conclusion

It is not surprising that, as smart sex technologies have developed, they have fostered the imagination of writers, researchers and designers about the future of sex. Smart sex toys are the stuff of fantasy. They have potential to augment human bodies to the point where physical sexual interactions – that are embodied and felt – can be enacted at a distance (potentially a vast distance). The very possibility of this evokes discussion about what we consider to be ‘real’ sex and whether our bodies need to be physically present with another person for us to determine that we have had sex with them. Across the body of literature engaged with the early development of smart sex toys, the point is made that these technologies have potential, over time, to redefine how we distinguish between ‘real’ and ‘not real’ sex or between ‘human’ and ‘object’ [10]. Smart sex devices augment what is possible for human bodies (i.e. touch at a distance), but the technology alone is not what determines the shape of networked sexual encounters. Human action, emotion and pleasure is also at play. Smart sex toys allow for humans and machines to interact sexually in new and expansive ways [10].

The extant literature on smart sex toys does not present evidence that these new technologies have engendered a radical, immediate change in human sexual cultures or human/object relations. However, smart sex toys are likely part of a gradual shift in the expectations that humans hold for their bodies and their sex lives that is occurring in relation to biomechanical and biodigital advancement [34]. We have seen this in other areas, including biomedical technologies. For instance, the existence, and widespread popularity, of Viagra, has gradually elevated expectations of what is ‘normal’ when it comes of male (erectile) sexual performance, particularly for older men [53].

Whether or not smart sex toys hold potential for radical disruption to gendered sexual cultures is contested. Some researchers see the sextech industry as a feminist led project that has potential to enhance female pleasure in heterosexual sex and enable creative, new approaches to exploring sexual pleasure [18, 19]. Others see smart sex toys as reinforcing normative sexual scripts that centre penis/vagina intercourse as the ‘ideal’ form of sexual relations and marginalise other experiences or bodies [25]. Importantly, research concerned with the potential for intimate data to be exposed, or for smart sex toys to enable rape by deception, reminds us that the uptake of these technologies happens within cultures defined by gender-based inequality and injustice. Irrespective of their disruptive potential, smart sex toys are a medium through which gendered violence can be enacted [3], just as concerns about exposure of data reflect the sexual stigma and shame that disproportionately burdens women and marginalised or stigmatised populations [13]. For this reason, it is important to highlight repeated calls made within this body of literature for the sextech industry to respond to safety and privacy concerns in the design and development of products, rather than placing responsibility on end-users to manage negative impacts [12, 39, 44]. The multi-disciplinary work included in this review highlights the value of multiple perspectives in informing sextech development, including the voices of a diverse range of potential users, ethicists and humanities researchers.

What the rise of smart sex toys could offer for health or sexual wellness is not clear due to the newness of these technologies and limited existing research. There is some indication that smart sex devices, especially in combination with immersive VR technology, may have potential to help people who struggle with sexual interaction or who have other barriers such as mobility [9]. However, this research is very new and the ways in which users engage with these technologies, and the impact on people’s lives, will need further consideration in future research with end users as the technology becomes more sophisticated and widely available.

Limitations

There are, of course, limitations to this review that should be considered. While we aimed to identify all relevant articles, it is possible that we have overlooked some. This is particularly the case with papers that were aligned with smart sex toys but used different terminology. There is a larger body of work looking at current and future technologies for neuro-sensory augmentation and haptic-technologies to simulate human touch [5] or facilitate sexual sensation and connection for people with limited movement [see 54]. While some aspects of this body of work were included in this review, we included only articles that discussed smart sex products.

Outlook

The current body of literature about smart sex toys reflects a creative moment in which researchers, designers, and sexuality educators are exploring potential for these technologies to relocate the centrality of the physical body in sex [30], shift centres of pleasure on the body [19], recast the gendered dynamics of sexual interactions [35], or expand sexual possibilities, including for people with limited mobility [9]. However, these potential benefits need to be considered alongside possible harms, including the risk of data breaches and sexual shaming, which are located in gender-based inequality and violence. Manufacturers of smart sex toys should be building processes for consent and data security into new products. Future academic work, that is multidisciplinary and connects technology developers and designers with artists and social/cultural researchers, should attend to user experiences to inform both future development and continue to explore the impact of smart sex products on human sexual cultures.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Rheingold H. Virtual reality: exploring the brave new technologies. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster Adult Publishing Group; 1991.

Yukita D et al. Teletongue: a lollipop device for remote oral interaction. In Proceedings of LSR 2016 International Conference on Love and Sex with Robots. 2017;40–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57738-8_4.

Nixon PG. Hell Yes!!!!!: playing away, teledildonics and the future of sex. In: Nixon P, Düsterhöft I, editors. Sex in the Digital Age. London Routledge. 2017; pp 201–11.

Ley M, Rambukkana N. Touching at a distance: digital intimacies, haptic platforms, and the ethics of consent. Sci Eng Ethics. 2021;27:1–17.

Cheok AD, Zhang EY. Electrical machine for remote kissing, and engineering measurement of its remote communication effects, including modified Turing test. J Future Robot Life. 2020;1(1):111–34.

Cheok AD, Zhang EY. Kissenger: Transmitting Kiss Through the Internet. In: Cheok, A.D. and Zhang, E.Y. (eds.) Human–Robot Intimate Relationships. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019; p.77–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-94730-3_4.

Samani HA, Parsani R, Rodriguez LT, Saadatian E, Dissanayake KH, Cheok AD. Kissenger: Design of a Kiss Transmission Device. Proc DIS 2012;48–57.

Giusto D, Pastorino C. Sex in the digital era: how secure are smart sex toys? ESET Research white papers. 2021. Available at: https://www.eset.com/fileadmin/ESET/IL/ESET_Smart-Sex-Toys_WP_PRESS.pdf.

Kuo C. Designing intimate touch technology (unpublished student research). Designing intimate touch technology (unpublished student research). Delft University of Technology, Delft. 2015. https://repository.tudelft.nl/islandora/object/uuid:b5bbac47-23e4-42cd-a212-2ae67ce39950.

Kaisar M. Bluetooth orgasms. MedieKultur: J Media Commun Res. 2021;37(71):143–60.

Flore J, Pienaar K. Data-driven intimacy: emerging technologies in the (re) making of sexual subjects and ‘healthy’sexuality. Health Sociol Rev. 2020;29(3):279–93.

Stardust Z, Albury K, Kennedy J. Public Interest Sex Tech Hackathon: Speculative Futures and Participatory Design. Australian Research Council Centre for Automated Decision-Making and Society, Queensland University of Technology, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology and Swinburne University of Technology. Brisbane, Australia. 2022. Available at: https://apo.org.au/node/318398.

Albury K, Stardust Z, Sundén J. Queer and feminist reflections on sextech. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2023;31(4):2246751.

Döring N. Sex toys. In: Lykins AD, editor. Encyclopedia of Sexuality and Gender. Springer International Publishing: Cham; 2021. p. 1–10.

Döring N. How is the COVID-19 pandemic affecting our sexualities? An overview of the current media narratives and research hypotheses Arch Sex Behav. 2020;49(8):2765–2778. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01790-z.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme Version. 2006;1(1):b92, 10.1.1.178.3100.

Bardzell J, Bardzell S. Pleasure is Your Birthright’: Digitally Enabled Designer Sex Toys as a Case of Third-Wave HCI,” in CHI 2011. Vancouver: ACM. 2011;257–266. https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/1978942.1978979.

Carpenter V, Homewood S, Overgaard M, Wuschitz S. From sex toys to pleasure objects. Proceedings of EVA Copenhagen 2018, 15–17 May, Politics of the Machines – Art and After. 2018. https://doi.org/10.14236/ewic/EVAC18.45.

Corti E, Parati I, Dils C. Lovewear: Haptic clothing that allows intimate exploration for movement-impaired people. Leonardo. 2023;56(2):139–46.

Döring N, Krämer N, Mikhailova V, Brand M, Krüger TH, Vowe G. Sexual interaction in digital contexts and its implications for sexual health: a conceptual analysis. Front Psychol. 2021;12:769732.

Duller N, Rodriguez-Amat JR. Sex machines as mediatized sexualities: Ethical and social implications. In: Eberwein T, Karmasin M, Krotz F, Rath M, editors. Responsibility and resistance: Ethics in mediatized worlds. Wiesbaden: Springer. 2019. pp. 221–239.

Evans L. ‘The embodied empathy revolution…’: pornography and the contemporary state of consumer virtual reality. Porn Studies. 2021;8(1):121–7.

Evans L. Virtual reality pornography: a review of health-related opportunities and challenges. Curr Sex Health Rep. 2023;15(1):26–35.

Faustino MJ. Rebooting an old script by new means: teledildonics—the technological return to the ‘coital imperative.’ Sex Cult. 2018;22(1):243–57.

Gesselman AN, Kaufman EM, Marcotte AS, Reynolds TA, Garcia JR. Engagement with emerging forms of sextech: Demographic correlates from a national sample of adults in the United States. J Sex Res. 2023;60(2):177–89.

Gidaris C. The Problem of Consent with Teledildonics and Adult Webcam Platforms. Surveill Soc. 2024;22(1):6–17.

Gomes L, Wu R. User evaluation of the neurodildo: a mind-controlled sex toy for people with disabilities and an exploration of its applications to sex robots. Robotics. 2018;7(3):46.

Liberati N. Teledildonics and digital intimacy: A phenomenological analysis of sexual relations through new digital devices. Glimpse. 2017;18:103–10.

Liberati N. Teledildonics and new ways of “being in touch”: A phenomenological analysis of the use of haptic devices for intimate relations. Sci Eng Ethics. 2017;23(3):801–23.

Liberati N. Making out with the world and valuing relationships with humans: Mediation theory and the introduction of teledildonics. Paladyn J Behav Rob. 2020;11(1):140–6.

Lupton D. Quantified sex: a critical analysis of sexual and reproductive self-tracking using apps. Cult Health Sex. 2015;17(4):440–53.

Marcotte AS, Kaufman EM, Campbell JT, Reynolds TA, Garcia JR, Gesselman AN. Sextech use as a potential mental health reprieve: the role of anxiety, depression, and loneliness in seeking sex online. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(17):8924.

Martins EE. I’m the operator with my pocket vibrator: Collective intimate relations on Chaturbate. Soc Media+ Soc. 2019;5(4):2056305119879989.

Pym T, James A, Waling A, Power J, Dowsett GW. Synced as a couple: Responsibility, control and connection in accounts of using wireless sex devices during heterosex. Sexualities. 2023;0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/13634607231218832.

Sparrow R, Karas L. Teledildonics and rape by deception. Law Innov Technol. 2020;12(1):175–204.

Stardust Z. Sex tech in an age of surveillance capitalism: Design, data and governance. In: Aggleton P, Cover R, Logie CH, Newman CE, Parker R, editors. Routledge Handbook of Sexuality. Gender: Health and Rights. Abingdon; 2024. p. 448–58.

Steensig A, Westh J. Intimate Sensory Technology in Long Distance Relationships–a Thesis Study in the Sensescape of Teledildonics: Thesis. Aalborg East: Aalborg University; 2016.

Sundén J. Play, secrecy and consent: theorizing privacy breaches and sensitive data in the world of networked sex toys. Sexualities. 2023;26(8):926–40.

Valente J, Wynn MA, Cardenas AA. Stealing, spying, and abusing: Consequences of attacks on internet of things devices. IEEE Secur Priv. 2019;17(5):10–21.

Varod S, Heruti RJ. The sextech industry and innovative devices for treating sexual dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-023-00731-3.

Watson ED, Séguin LJ, Milhausen RR, Murray SH. The impact of a couple’s vibrator on men’s perceptions of their own and their partner’s sexual pleasure and satisfaction. Men Masculinities. 2016;19(4):370–83.

Wilson-Barnao C, Collie N. The droning of intimacy: bodies, data, and sensory devices. Continuum. 2018;32(6):733–44.

Wynn M, Tillotson K, Kao R, Calderon A, Murillo A, Camargo J et al. Sexual intimacy in the age of smart devices: are we practicing safe IoT?. In IoTS&P ‘17: Proceedings of the 2017 Workshop on Internet of Things Security and Privacy, Dallas, TX. 2017;25–30.

Zhang EY, Nishiguchi S, Cheok AD, Morisawa Y, eds. Kissenger–development of a real-time internet kiss communication interface for mobile phones. Love and Sex with Robots: Second International Conference, LSR 2016, London, UK, December pp 19–20. 2017.

Zhou X, Zhao J, Liang X. Cyberphysical Human Sexual Behavior Acquisition System (SeBA): Development and Implementation Study in China. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(4):e12677.

Stardust Z, Albury K. Kennedy J. Sex tech entrepreneurs: Governing intimate data in start-up culture. New Media & Society; 2023. p. 14614448231164408.

Ronen S. Gendered morality in the sex toy market: Entitlements, reversals, and the irony of heterosexuality. Sexualities. 2021;24(4):614–35.

Tembo KD. On the Commodification of Sexual Wellness: Race, Gender, and the Engineering of Consent. In: Shei C, Schnell J, editors. The Routledge Handbook of Language and Mind Engineering: Routledge, London; 2024. p. 121–36.

Patton C, McVey M, Hackett C. Enough of the ‘snake oil’: Applying a business and human rights lens to the sexual and reproductive wellness industry. Bus Hum Rights J. 2022;7(1):12–28.

Levy J, Romo-Avilés N. “A good little tool to get to know yourself a bit better”: a qualitative study on users’ experiences of app-supported menstrual tracking in Europe. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1–11.

McMillan C. Monitoring female fertility through ‘Femtech’: the need for a whole-system Approach to Regulation. Med Law Rev. 2022;30(3):410–33.

Gross G, Blundo R. Viagara: Medical technology constructing aging masculinity. J Sociol Soc Welf. 2005;32:85.

Moscatelli A, Nimbi FM, Ciotti S, Jannini EA. Haptic and somesthetic communication in sexual medicine. Sex Med Rev. 2021;9(2):267–79.

Acknowledgements

The research for this paper was, in part, funded with a grant from the Australian Research Council (DP190102027). We are grateful to Gary W. Dowsett, Jayne Lucke, and Anne-Maree Farrell for their role on this project.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JP and TP conducted the literature search. All authors were involved in discussion of the key themes evident in the literature and interpretation of their meaning and significance. JP drafted the manuscript with input from TP. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Human and Animals and Inform Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Power, J., Pym, T., James, A. et al. Smart Sex Toys: A Narrative Review of Recent Research on Cultural, Health and Safety Considerations. Curr Sex Health Rep (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-024-00392-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-024-00392-3