Abstract

Purpose of the Review

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a chronic, painful joint disease that affects approximately 40% of adults over 70 year. Age is the strongest predictor of OA, while obesity is considered the primary preventable risk factor for OA. Both conditions are associated with abnormal innate immune inflammatory responses that contribute to OA progression and are the focus of this review.

Recent Findings

Recent studies have identified risk factors for OA progression including increased innate immune responses secondary to aging-associated myeloid skewing, obesity-related myeloid activation, and synovial tissue hyperplasia with activated macrophage infiltration. Toll-like receptor (TLR)4-induced catabolic responses also play a significant role in OA.

Summary

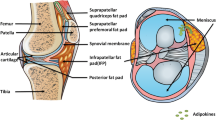

The complex interplay between obesity and aging-associated macrophage activation, pro-inflammatory cytokine production from TLR-driven responses, and adipokines leads to a vicious cycle of synovial hyperplasia, macrophage activation, cartilage catabolism, infrapatellar fat pad fibrosis, and joint destruction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- OA:

-

Osteoarthritis

- DMOADs:

-

Disease-modifying anti-osteoarthritis drugs

- TLR:

-

Toll-like receptor

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- TNF-α:

-

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha

- LPS:

-

Lipopolysaccharide

- IFP:

-

Infrapatellar fat pad

- PGE2:

-

Prostaglandin E2

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- MMPs:

-

Metalloproteinases

- DMM:

-

Destabilized medial meniscus

- HFD:

-

High-fat diet

- CIs:

-

Confidence intervals

- ceMRI:

-

Contrast-enhanced MRI

- US:

-

Ultrasound

- SPECT-CT:

-

Single-photon emission computed tomography

- Nf-ĸB:

-

Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain enhancer of activated B cells

- iNOS:

-

Nitric oxide synthase

- COX-2:

-

Cyclooxygenase-2

- CCL:

-

Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand

- CXCL:

-

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand

- IL-1Ra:

-

Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist

- IP-10:

-

Interferon-gamma-inducible protein

- MCP-1:

-

Monocyte chemotactic protein-1

- DAMPS:

-

Danger-associated molecular patterns

- HMGB1:

-

Hyaluronan and high-mobility group box chromosomal protein

- FFA:

-

Free fatty acids

- SDF1:

-

Stromal-derived-factor-1

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Berenbaum F. Osteoarthritis as an inflammatory disease (osteoarthritis is not osteoarthrosis!). Osteoarthritis and Cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 2013;21(1):16–21.

Sokolove J, Lepus CM. Role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis: latest findings and interpretations. Ther Adv Musculoskelet dis. 2013;5(2):77–94.

Franceschi C, Capri M, Monti D, et al. Inflammaging and anti-inflammaging: a systemic perspective on aging and longevity emerged from studies in humans. Mech Ageing dev. 2007;128(1):92–105.

Florez H, Troen BR. Fat and inflammaging: a dual path to unfitness in elderly people? J am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(3):558–60.

Hotamisligil GS, Shargill NS, Spiegelman BM. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science. 1993;259(5091):87–91.

Visser M. Higher levels of inflammation in obese children. Nutrition. 2001;17(6):480–1.

Visser M, Bouter LM, McQuillan GM, Wener MH, Harris TB. Elevated C-reactive protein levels in overweight and obese adults. Jama. 1999;282(22):2131–5.

Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW Jr. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(12):1796–808.

Robinson WH, Lepus CM, Wang Q, et al. Low-grade inflammation as a key mediator of the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;10:580–592.

Franceschi C. Inflammaging as a major characteristic of old people: can it be prevented or cured? Nutr rev. 2007;65(12 Pt 2):S173–6.

Franceschi C, Bonafe M, Valensin S, et al. Inflamm-aging. An evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;908:244–54.

Gomez CR, Hirano S, Cutro BT, et al. Advanced age exacerbates the pulmonary inflammatory response after lipopolysaccharide exposure. Crit Care med. 2007;35(1):246–51.

Gomez CR, Nomellini V, Baila H, Oshima K, Kovacs EJ. Comparison of the effects of aging and IL-6 on the hepatic inflammatory response in two models of systemic injury: scald injury versus i.p. LPS administration. Shock. 2009;31(2):178–84.

Wu D, Ren Z, Pae M, et al. Aging up-regulates expression of inflammatory mediators in mouse adipose tissue. J Immunol. 2007;179(7):4829–39.

Chuckpaiwong B, Charles HC, Kraus VB, Guilak F, Nunley JA. Age-associated increases in the size of the infrapatellar fat pad in knee osteoarthritis as measured by 3T MRI. J Orthop res. 2010;28(9):1149–54.

Cowan SM, Hart HF, Warden SJ, Crossley KM. Infrapatellar fat pad volume is greater in individuals with patellofemoral joint osteoarthritis and associated with pain. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35(8):1439–42.

Pan F, Han W, Wang X, et al. A longitudinal study of the association between infrapatellar fat pad maximal area and changes in knee symptoms and structure in older adults. Ann Rheum dis. 2015;74(10):1818–24.

Han W, Cai S, Liu Z, et al. Infrapatellar fat pad in the knee: is local fat good or bad for knee osteoarthritis? Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16(4):R145.

Cai J, Xu J, Wang K, et al. Association between infrapatellar fat pad volume and knee structural changes in patients with knee osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(10):1878–84.

Teichtahl AJ, Wulidasari E, Brady SR, et al. A large infrapatellar fat pad protects against knee pain and lateral tibial cartilage volume loss. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:318.

Wang J, Han W, Wang X, et al. Mass effect and signal intensity alteration in the suprapatellar fat pad: associations with knee symptoms and structure. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 2014;22(10):1619–26.

• Eymard F, Pigenet A, Citadelle D, et al. Knee and hip intra-articular adipose tissues (IAATs) compared with autologous subcutaneous adipose tissue: a specific phenotype for a central player in osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(6):1142–1148. This study provides the first evidence that intra-articular fat tissue differs from subcutaneous fat in terms of inflammation, vascularization, and leukocyte infiltration.

Fu Y, Huebner JL, Kraus VB, Griffin TM. Effect of aging on adipose tissue inflammation in the knee joints of F344BN rats. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71(9):1131–1140.

Gross JB, Guillaume C, Gegout-Pottie P, et al. The infrapatellar fat pad induces inflammatory and degradative effects in articular cells but not through leptin or adiponectin. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017;35(1):53–60.

Bastiaansen-Jenniskens YM, Clockaerts S, Feijt C, et al. Infrapatellar fat pad of patients with end-stage osteoarthritis inhibits catabolic mediators in cartilage. Ann Rheum dis. 2012;71(2):288–94.

• Barboza E, Hudson J, Chang WP, et al. Pro-fibrotic infrapatellar fat pad remodeling without M1-macrophage polarization precedes knee osteoarthritis in diet-induced obese mice. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(6):1221–1232. This study reveals that high fat diet in male C57BL/6 mice induces infrapatellar fat pad fibrosis but not M1 macrophage polarization or infiltration.

Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Naimark A, Walker AM, Meenan RF. Obesity and knee osteoarthritis. The Framingham study. Ann Intern med. 1988;109(1):18–24.

Powell A, Teichtahl AJ, Wluka AE, Cicuttini FM. Obesity: a preventable risk factor for large joint osteoarthritis which may act through biomechanical factors. Br J Sports med. 2005;39(1):4–5.

Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Dieppe PA, et al. Osteoarthritis: new insights. Part 1: the disease and its risk factors. Ann Intern med. 2000;133(8):635–46.

Oliveria SA, Felson DT, Cirillo PA, Reed JI, Walker AM. Body weight, body mass index, and incident symptomatic osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Epidemiology. 1999;10(2):161–6.

Murphy L, Schwartz TA, Helmick CG, et al. Lifetime risk of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(9):1207–13.

Felson DT, Zhang Y, Anthony JM, Naimark A, Anderson JJ. Weight loss reduces the risk for symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in women. The Framingham study. Ann Intern med. 1992;116(7):535–9.

Toda Y, Toda T, Takemura S, Wada T, Morimoto T, Ogawa R. Change in body fat, but not body weight or metabolic correlates of obesity, is related to symptomatic relief of obese patients with knee osteoarthritis after a weight control program. J Rheumatol. 1998;25(11):2181–6.

Richter M, Trzeciak T, Owecki M, Pucher A, Kaczmarczyk J. The role of adipocytokines in the pathogenesis of knee joint osteoarthritis. Int Orthop. 2015;39(6):1211–7.

Poonpet T, Honsawek S. Adipokines: biomarkers for osteoarthritis? World J Orthop. 2014;5(3):319–27.

Buckwalter JA, Lotz M, Stoltz J-F. Osteoarthritis, inflammation and degradation: a continuum, vol. 70. Washington, DC: IOS; 2007.

Henrotin YE, Bruckner P, Pujol JP. The role of reactive oxygen species in homeostasis and degradation of cartilage. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2003;11(10):747–55.

You T, Nicklas BJ. Chronic inflammation: role of adipose tissue and modulation by weight loss. Curr Diabetes rev. 2006;2(1):29–37.

• Perez-Perez A, Vilarino-Garcia T, Fernandez-Riejos P, Martin-Gonzalez J, Segura-Egea JJ, Sanchez-Margalet V. Role of leptin as a link between metabolism and the immune system. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2017. Mar 4. pii: S1359–6101(16)30163–0. doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2017.03.001 [Epub ahead of print]. An excellent review on the metabolic and immunomodulatory effects of leptin.

Presle N, Pottie P, Dumond H, et al. Differential distribution of adipokines between serum and synovial fluid in patients with osteoarthritis. Contribution of joint tissues to their articular production. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 2006;14(7):690–5.

Dumond H, Presle N, Terlain B, et al. Evidence for a key role of leptin in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(11):3118–29.

Griffin TM, Huebner JL, Kraus VB, Guilak F. Extreme obesity due to impaired leptin signaling in mice does not cause knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(10):2935–44.

Luo Y, Liu M. Adiponectin: a versatile player of innate immunity. J Mol Cell Biol. 2016;8(2):120–8.

Yusuf E, Ioan-Facsinay A, Bijsterbosch J, et al. Association between leptin, adiponectin and resistin and long-term progression of hand osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum dis. 2011;70(7):1282–4.

Calvet J, Orellana C, Gratacos J, et al. Synovial fluid adipokines are associated with clinical severity in knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study in female patients with joint effusion. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18(1):207.

Staikos C, Ververidis A, Drosos G, Manolopoulos VG, Verettas D-A, Tavridou A. The association of adipokine levels in plasma and synovial fluid with the severity of knee osteoarthritis. Rheumatology. 2013;52(6):1077–83.

de Boer TN, van Spil WE, Huisman AM, et al. Serum adipokines in osteoarthritis; comparison with controls and relationship with local parameters of synovial inflammation and cartilage damage. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 2012;20(8):846–53.

•• Sarmanova A, Hall M, Moses J, Doherty M, Zhang W. Synovial changes detected by ultrasound in people with knee osteoarthritis—a meta-analysis of observational studies. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2016;24(8):1376–83. This meta-analysis includes 24 studies and concludes that ultrasound-detected knee effusions, synovial hypertrophy, and Doppler signals correlate with significantly increased prevalence of OA compared to asymptomatic controls.

Wallace G, Cro S, Dore C, et al. Associations between clinical evidence of inflammation and synovitis in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: a substudy of the VIDEO trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016. Dec 20. doi:10.1002/acr.23162. [Epub ahead of print].

Jaremko JL, Jeffery D, Buller M, et al. Preliminary validation of the knee inflammation MRI scoring system (KIMRISS) for grading bone marrow lesions in osteoarthritis of the knee: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. RMD Open. 2017;3(1):e000355.

•• Damman W, Liu R, Bloem JL, Rosendaal FR, Reijnierse M, Kloppenburg M. Bone marrow lesions and synovitis on MRI associate with radiographic progression after 2 years in hand osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum dis. 2017;76(1):214–7. This study shows that bone lesions of grade 2/3 and synovitis of the distal and proximal interphalangeal joints detected by contrast-enhanced MRI are associated with radiographic progression at 2 years.

Liu R, Damman W, Reijnierse M, Bloem JL, Rosendaal FR, Kloppenburg M. Bone marrow lesions on magnetic resonance imaging in hand osteoarthritis are associated with pain and interact with synovitis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2017. Feb 12. pii S1063–4584(17)30853 [Epub ahead of print].

Mancarella L, Addimanda O, Cavallari C, Meliconi R. Synovial inflammation drives structural damage in hand osteoarthritis: a narrative literature review. Curr Rheumatol Rev. 2016. Dec 9 [Epub ahead of print].

•• Felson DT, Niu J, Neogi T, et al. Synovitis and the risk of knee osteoarthritis: the MOST study. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2016;24(3):458–64. Synovitis grade >3 (0-9) on baseline MRIs (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.2, 2.1, p = 003) increased the risk of incident OA at 84 months.

Sharma L, Hochberg M, Nevitt M, et al. Knee tissue lesions and prediction of incident knee osteoarthritis over 7 years in a cohort of persons at higher risk. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2017. Feb 14. pii. S1063–4584(17)30551–8 [Epub ahead of print].

• Kraus VB, Mc Daniel G, Huebner JL, et al. Direct in vivo evidence of activated macrophages in human osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 2016;24(9):1613–21. This study provides the first direct evidence for infiltration of activated macrophages in knee OA. Increasing numbers of activated macrophages were associated with increases in radiographic knee severity and with pain severity.

Schlaak JF, Pfers I, Meyer Zum Buschenfelde KH, Marker-Hermann E. Different cytokine profiles in the synovial fluid of patients with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and seronegative spondylarthropathies. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1996;14(2):155–62.

Kapoor M, Martel-Pelletier J, Lajeunesse D, Pelletier JP, Fahmi H. Role of proinflammatory cytokines in the pathophysiology of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7(1):33–42.

Fernandes JC, Martel-Pelletier J, Pelletier JP. The role of cytokines in osteoarthritis pathophysiology. Biorheology. 2002;39(1–2):237–46.

Rahmati M, Mobasheri A, Mozafari M. Inflammatory mediators in osteoarthritis: a critical review of the state-of-the-art, current prospects, and future challenges. Bone. 2016;85:81–90.

• Bernardini G, Benigni G, Scrivo R, Valesini G, Santoni A. The multifunctional role of the chemokine system in arthritogenic processes. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2017;19(3):11. Excellent and comprehensive review of chemokines in arthritis.

Kim HA, Cho ML, Choi HY, et al. The catabolic pathway mediated by toll-like receptors in human osteoarthritic chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(7):2152–63.

Schelbergen RF, Blom AB, van den Bosch MH, et al. Alarmins S100A8 and S100A9 elicit a catabolic effect in human osteoarthritic chondrocytes that is dependent on toll-like receptor 4. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(5):1477–87.

Liu-Bryan R, Terkeltaub R. Chondrocyte innate immune myeloid differentiation factor 88-dependent signaling drives procatabolic effects of the endogenous toll-like receptor 2/toll-like receptor 4 ligands low molecular weight hyaluronan and high mobility group box chromosomal protein 1 in mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(7):2004–12.

Gomez R, Villalvilla A, Largo R, Gualillo O, Herrero-Beaumont G. TLR4 signalling in osteoarthritis—finding targets for candidate DMOADs. Nat rev Rheumatol. 2015;11(3):159–70.

Goldring MB. Chondrogenesis, chondrocyte differentiation, and articular cartilage metabolism in health and osteoarthritis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet dis. 2012;4(4):269–85.

Sohn DH, Sokolove J, Sharpe O, et al. Plasma proteins present in osteoarthritic synovial fluid can stimulate cytokine production via toll-like receptor 4. Arthritis res Ther. 2012;14(1):R7.

Kim F, Pham M, Luttrell I, et al. Toll-like receptor-4 mediates vascular inflammation and insulin resistance in diet-induced obesity. Circ res. 2007;100(11):1589–96.

Harte AL, da Silva NF, Creely SJ, et al. Elevated endotoxin levels in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Inflamm (Lond). 2010;7:15.

Barreto G, Sandelin J, Salem A, Nordstrom DC, Waris E. Toll-like receptors and their soluble forms differ in the knee and thumb basal osteoarthritic joints. Acta Orthop. 2017;17:1–8.

Furman BD, Strand J, Hembree WC, Ward BD, Guilak F, Olson SA. Joint degeneration following closed intraarticular fracture in the mouse knee: a model of posttraumatic arthritis. J Orthop res. 2007;25(5):578–92.

Acknowledgements

The authors are supported by VA PECASE Award (MBH), Presbyterian Health Foundation Bridge Award (MBH), NIH (National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases grant R03AR066828 and National Institute on Aging grant R01AG049058) (TMG), and Children’s Hospital Foundation Award (EK).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

E. Kalaitzoglou, T.M. Griffin, and M.B. Humphrey declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any primary human or animal studies.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Osteoarthritis

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kalaitzoglou, E., Griffin, T.M. & Humphrey, M.B. Innate Immune Responses and Osteoarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 19, 45 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-017-0672-6

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-017-0672-6