Abstract

Purpose of Review

We summarized recent findings on insufficient sleep and insomnia, two prominent sleep issues that impact public health. We demonstrate the socio-ecologial impact of sleep health with findings on gender and couples’ relationships as exemplars.

Recent Findings

Robust gender differences in sleep duration and insomnia are due to biological and socio-ecological factors. Gender differences in insufficient sleep vary by country of origin and age whereas gender differences in insomnia reflect minoritized identities (e.g., sexual, gender). Co-sleeping with a partner is associated with longer sleep and more awakenings. Gender differences and couples’ sleep were affected by intersecting social and societal influences, which supports a socio-ecological approach to sleep.

Summary

Recent and seminal contributions to sleep health highlight the importance of observing individual sleep outcomes in a socio-ecological context. Novel methodology, such as global measures of sleep health, can inform efforts to improve sleep and, ultimately, public health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sleep health is a key health indicator across affective, cardiovascular, endocrinal, immune, and neurodegenerative aspects of health [1••, 2]. Several parameters comprise sleep health (e.g., satisfaction, duration, timing). Parameters are independently and collectively associated with physical, mental, and neurobehavioral health outcomes [3, 4••, 5]. Poor sleep health is a public health concern [1••, 6, 7]. However, dimensions of sleep health are modifiable, which makes improving sleep health an excellent mechanism for improving public health. [1••, 7, 8].

Sleep health is influenced by several factors across individual, interpersonal, and social/societal domains [1••, 9••]. Observing sleep health through this socio-ecological framework clarifies associations within and among individual and micro/macro levels of influence. For example, gender differences (individual) in sleep health are influenced by family roles (interpersonal) and policies such as family leave and health care (societal). Much of sleep research focuses on the individual level; however, recent work focused on gender, couples, and community and policy highlights the importance of observing sleep within a socio-ecological framework.

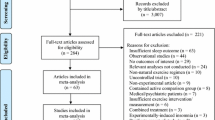

The aim of this article is to review new developments in sleep health research. We limit our review to the adult population and to new developments in insufficient sleep and insomnia as these two domains cut across many components of sleep health and have high public health relevance. We provide a brief overview of prevalence rates followed by recent research on individual differences, with a focus on gender, because gender differences in sleep outcomes begin as early as adolescence [10] and may be influenced by social contexts across the lifespan. We then highlight recent research that demonstrates how individual differences are mitigated by social context. In particular, close social contexts, such as co-sleeping with a partner and relationship functioning, are increasingly important to consider in the context of insufficient sleep and insomnia. As such, our overview on insufficient sleep and insomnia includes emergent and novel findings on the role of romantic relationships in mitigating or exacerbating good sleep health.

Insufficient Sleep Duration

Sleep experts recommend that adults obtain 7–9 h of sleep per night (7–8 for older adults). About 30–35% of adults have insufficient sleep (i.e., less than 7 h; [11, 12]). Prevalence rates of short or insufficient sleep appear to be rising [13]. Insufficient sleep is not itself a diagnosable disorder; however, the high prevalence highlights a critical target for improving the health of the population. Insufficient sleep is associated with poorer self-rated health [14], heightened risk of depression [15], type 2 diabetes [16], cardiovascular disease [17, 18], and early mortality [19,20,21]. Cross-sectional associations are further strengthened by robust evidence that insufficient sleep precedes health outcomes. For example, a meta-analysis of 15 prospective studies revealed that short sleep duration (< 7 h) increased the risk for coronary artery disease morbidity and mortality compared to normal sleep duration (7–9 h; 22]. Importantly, these relationships between insufficient sleep and mental and physical health outcomes do not seem to be due to sex, age, or other factors known to be associated with the aforementioned health outcomes, such as smoking, body mass index, education, exercise, and alcohol use [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Sleep duration is also influenced by multiple individual, social, and societal factors. As highlighted below, the prevalence of insufficient sleep varies across gender, race, and other demographics.

Gender Differences

Race, marital status, number of children in the household, residing region, and level of education predict sleep duration, with Black Americans being at higher risk of short sleep duration than White Americans [23]. Women tend to report needing longer sleep [24], but sex-based disparities in sleep duration may be age-dependent. A recent electrocardiogram (ECG) study on a large Japanese cohort (n = 68,604) found that women get less sleep than men of similar ages and demonstrated that this difference is more substantial after the age of 30 [25].

However, a global study of nearly 70,000 adults who wore smart wristbands found that women may sleep longer than men across the lifespan. This study also found that women experience more nighttime awakenings, particularly from young to middle adulthood, which was moderated by parenting status in women but not in men [26•]. Importantly, this time period is often marked by child-rearing, which is associated with increased psychological and behavioral demands for women, many of which impact sleep [27, 28]. However, parenting status alone did not explain the gender difference in nighttime awakenings, indicating multiple factors of sleep duration. Furthermore, mid-life women may experience hormonal and physiological symptoms associated with menopause that contribute to sleep disturbances, such as nighttime vasomotor symptoms (e.g., night sweats) [29]. It is also important to note that these studies not only suggest different findings regarding sex differences in sleep duration, but they also employed different methods of assessing sleep duration. While ECG characterizes sleep/wake states using on cardiorespiratory signals, smart wristbands determine sleep/wake states based on movement. These measurements therefore reflect different mechanisms that underly sleep. These differential findings emphasize the importance for integrated global assessments of gender-based disparities in insufficient sleep duration.

Gender differences in sleep duration also vary by country of origin. Seminal works have found that women report longer sleep duration in most OECD countries (i.e., Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; an intergovernmental organization that consists of democratic countries with free-market economies). Exclusions to this finding include Japan, India, Mexico, and Estonia [30,31,32,33]. Country of origin impacts gender differences in sleep duration because of differences in traditional gender expectations, such as division of housework or child-rearing [34, 35]. Seminal works on geography-based gender differences facilitate understanding of recent findings on gender differences in sleep duration.

Finally, individual gender differences in sleep duration are linked to differential downstream consequences. Recent findings suggest that women with same-sex partners felt less rested when sleeping less than 7 h than women with different-sex partners who slept the same amount. There were no differences in the relationship between sleep duration and feeling rested between men with different-sex partners and men with same-sex partners. These findings were not due to differences in sleep duration. Rather, not feeling rested was attributable to larger societal factors; women with same-sex partners felt less rested in states with less sexual minority support. [36•] Thus, consideration of gender disparities in a close social context, and broader state-level values and policy, clarifies one potential mechanism for gender differences in sleep outcomes.

Sleep Duration and Couples

As indicated above, expanding beyond the individual level reveals multiple influences on sleep duration. Consideration of couples’ sleep habits is one way the sleep field is contextualizing individual sleep. Simply sharing a bed with a partner contributes to higher levels of sleep fragmentation (arousals after sleep onset; 34), which in turn decreases total sleep duration. This phenomenon is likely more prominent in female partners [38]. On the other hand, people who share a bed with their partner report total sleep time increases when co-sleeping [39, 40]. Similarly, a study of Hispanic/Latino adults found that living with a partner predicted better sleep health in general, including sleeping 7–9 h per night. These associations were strongest among women [41•]. However, individual-level sleep is also affected by the emotional health of the relationship. Co-sleeping may not affect all relationships equally. A seminal review on couples’ sleep indicates that relationship functioning (e.g., marital satisfaction) influences chronobiological (i.e., one’s sleep timing), behavioral, psychological, and physiological processes that underly sleep, such that individuals in higher functioning relationships report better sleep outcomes compared to those in poorer functioning relationships [42]. Thus, the physical presence of a partner and relationship characteristics (e.g., satisfaction, conflict) can impact sleep duration at the individual level.

Identifying the most robust couple-level influences on individual-level sleep involves objective (e.g., polysomnography) and subjective (e.g., daily diaries, questionnaires) sleep assessments in both partners. Until recently, most studies relied on individual, subjective assessments. A recent study of sleep architecture (i.e., sleep stages 1–2, 3–4, and rapid eye movement (REM)), assessed via polysomnography, in young heterosexual couples showed differences in sleep when co-sleeping [43]. Co-sleeping was associated with more REM sleep in bed partners, despite increased movements and awakenings compared to when the individual slept alone. Individuals who had less social support received the most benefits to REM sleep from co-sleeping. Because more REM sleep predicts better subjective sleep quality, the benefits of sleeping with a partner may outweigh potential sleep loss, particularly for those with less support from their network [44].

Assessment of couple-level sleep reveals parallel findings with other couple-level health outcomes. That is, couples tend to have similar (or concordant) health behaviors [45]. Indeed, a recent daily diary study of heterosexual couples showed positive covariation in sleep duration [46]. One partner’s total sleep time corresponded to the other partner’s total sleep time. Also consistent with the broader literature on couples and social control, when a female partner’s sleep was longer or shorter than usual, their male partner’s sleep was also longer or shorter than usual. Changes in the male partner’s sleep duration did not significantly predict the female partner’s sleep.

Taken together, emergent findings on couples’ sleep demonstrate that sleep duration covaries within partners and that individual differences such as gender and social support influence the extent to which couple-level sleep patterns affect an individual’s sleep duration. Dyadic approaches (e.g., actor-partner modeling) in unique socio-ecological contexts highlight additional partner characteristics that impact sleep duration. For example, when examining advanced cancer patients and their spousal caretakers, a spouse’s anxiety predicted their own, and their partner’s sleep duration [47]. Similarly, employment status (i.e., employed vs. unemployed) can affect an individual’s sleep and their partner’s sleep, but there were gender differences in these relationships. A male partner’s employment status predicted longer actigraphy-assessed sleep duration for women, but a female partner’s employment status was associated with increased sleep problems for men [48].

Sleep Duration Summary

Sleep duration is strongly linked to physical and mental health. Individual differences (e.g., sex, race, age) in sleep duration vary depending on the social context, such as country of origin, perceived support from government regulations, relationship status, and relationship functioning. Co-sleeping with a partner is linked to increased sleep duration, but characteristics such as a partner’s anxiety may diminish such benefits. Additionally, social context (e.g., sexual orientation and living in a state with less sexual minority support) may affect the amount of sleep needed to feel rested. Overall, recent research on gender differences further clarifies how age and gender roles impact sleep duration, highlighting the importance of social context when examining gender differences. Studies on couples’ sleep are less common, but emerging research provides further support that an individual’s sleep duration varies depending on co-sleeping status and characteristics of the close partnership.

Insomnia

Insufficient sleep duration can originate due to diminished opportunities for sleep; however, it can also emerge despite sufficient opportunity—a hallmark characteristic of insomnia [49]. Insomnia, which is classified as a disorder, is defined by deficits across multiple parameters: dissatisfaction with sleep quality or quantity, difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep, or early morning awakenings. It is commonly associated with pre-sleep cognitive and somatic arousal at bedtime [50], excessive daytime sleepiness, and impaired daytime functioning [51, 52•]. Insomnia symptoms are considered clinically significant when the sleep disturbance causes significant distress or impairment in important areas of functioning and the difficulty occurs for three nights per week for at least 3 months [53]. Insomnia is a prevalent and costly sleep disorder [54, 55], with 8–10% of the population suffering from chronic insomnia [56, 57]. Additionally, insomnia is associated with heightened risk for adverse mental health outcomes (i.e., depression, anxiety), irrespective of sleep duration.

When insomnia is paired with insufficient/short sleep duration, the health consequences of insomnia are more severe [58]. Compared to individuals with insomnia who report sufficient sleep duration, individuals with insomnia who report short sleep duration are at higher risk of hypertension [59, 60], diabetes [61], and mortality [62]. More specifically, a multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis found that women with insomnia were at an 18% increased risk for subclinical atherosclerotic disease compared to men with insomnia [63•]. Thus, like insufficient sleep duration, insomnia is increasingly understood as a systemic health problem [2] that affects cardiometabolic, immune, and neurodegenerative aspects of health [64].

Gender Differences

Across the lifespan, women report higher rates of insomnia symptoms compared to men [65]: during adolescence, female individuals experience a 3.6 × increase in insomnia versus a 2.1 × increase in male individuals [66]. In the general adult population, women have 1.58 higher odds of receiving a diagnosis of insomnia [67], and gender remains a significant predictor of insomnia in older adults [68].

Advances in neuroscience inform our understanding of how sex differences in the brain contribute to the high prevalence of insomnia among women. Fluctuation of the female sex hormone, estradiol, is associated with poor sleep quality during the midluteal phase of the menstrual cycle and may contribute to increased vulnerability to sleep problems in women of child-bearing age [69]. Similar sex hormone fluctuations in the brain structures related to circadian regulation may contribute to increased vulnerability to insomnia during pregnancy, postpartum, [70] and menopause [68]. Furthermore, recent studies identified sex differences in neuroendocrinal, circadian, and emotional regulation processes associated with restless REM sleep [71], which may contribute to the gender disparity of insomnia in women.

Neurobiological factors alone cannot explain the gender disparity in insomnia [72]. For example, perpetuating factors of insomnia differ by gender: men are more likely to hold false beliefs about the origin and management of insomnia, cope with poor health behaviors (e.g., smoking), and nap during the day; women reported higher pre-sleep arousal, higher perception of severity, more emotional dysregulation, and more use of sleep hygiene strategies [52•, 66, 67]). Furthermore, increased parity (i.e., number of children) has been associated with decreased insomnia in Chinese older adult women [73], but with increased insomnia in middle-aged women in the USA [74], indicating a familial-level influence on sleep health.

The gender disparity in insomnia may be amplified in populations with intersectional identities, exemplifying, again, the influence of socio-ecological factors of sleep health [75]. For example, female active US military service members report higher rates of insomnia than male counterparts [76], and female combat veterans utilize more sleep aids than men [77]. In Black, middle-aged women in the USA, higher levels of perceived racism were associated with increased odds of clinically significant insomnia [78]. Indeed, sexual and gender minority populations are two times more likely to be diagnosed with insomnia than their cisgender counterparts [79]—although there are gaps in this literature [80]. These findings speak to the importance of investigating sleep health across intersecting socio-ecological domains (i.e., societal and social levels factors) and the importance of assessing intersectional identity across those domains in the context of health outcomes [81].

The global COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted existing socio-economic, gender, and ethno-racial inequities in sleep health [82, 83]). Prevalence of reported insomnia symptoms during the pandemic ranges from 25 to 37%, with particularly high rates of insomnia symptoms among female health care workers [84, 85]. Furthermore, gender differences of insomnia among front-line health care workers were accounted for by family responsibilities and work conditions [86•].

The COVID-19 pandemic has also highlighted moderating effects across gender that contradict the established relationship between insomnia and gender: a longitudinal study of the Italian population during lockdown conditions found that women reported higher distress and insomnia symptoms early during the lockdown, but demonstrated resilience at seven weeks, whereas men’s scores declined over time [87]. Likewise, a meta-analysis of sleep problems in COVID-19 patients in affected countries found that male sex moderated the relationship between COVID-19 and insomnia [88]. Outside the context of a pandemic, a similar moderating effect has been found in insomnia associated with tinnitus [89], indicating that gender plays a role in the comorbidity of insomnia with medical conditions.

Insomnia and Couples

Studies on insomnia within a couples’ context are sparse; however, limited findings suggest that the effects of insomnia go beyond the sleep of the insomnia patient. For example, within romantic dyads, an insomnia patient’s partner is at risk for disrupted sleep, ostensibly due to their partner’s insomnia. Although insomnia patients are sensitive sleepers, patients cause 25% more partner awakenings than they experience from their partner [90••]. These findings highlight another way in which the social context (having a partner with insomnia) can affect individual sleep health.

Emerging research on insomnia treatment suggests that considering the social context can also inform treatment choices. A study of pregnant women experiencing insomnia found high concordance of preferred treatment between partners, with partner preference significantly predicting women’s choices. Majority of women and partners indicated that they would prefer cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia over pharmacotherapy [91]. These findings support the large literature that suggests concordance in partners’ health behaviors and demonstrates the importance in incorporating partner input into the treatment plan [45]. Results from an ongoing randomized trial will demonstrate how integrating partners into treatment influences patient and partner outcomes [92].

Consistent with trends in the field of sleep medicine, improving sleep health involves focus on improving multiple sleep parameters. This is true for insomnia and sleep apnea [93,94,95]. Although beyond the scope of the current study, work on sleep apnea (a condition characterized by repeated stopping and starting of breathing during sleep) is briefly highlighted because it is relevant for gender, couples, and presents with comorbid insomnia [96, 97]. Including partners in apnea treatment is beneficial [98,99,100] and increasingly common [101]. At least one clinical trial is already examining whether CPAP usage improves a partner’s sleep health, including symptoms of insomnia [101].

Insomnia Summary

Heterogenous presentations of insomnia with differing health consequences demonstrate the importance of identifying multiple factors contributing to the development and perpetuation of insomnia and promotion of sleep health. While there is evidence from the neuroscience paradigm of gender differences in the brain that may contribute to the gender disparity, there is also evidence that factors across the socio-ecological model of health affect insomnia, such as the intersection of work environment and family responsibilities in female health care workers and comorbid conditions in male patients. Novel research in couples demonstrates that insomnia is disruptive to the sleep of both patient and partner. Emerging literature suggests that partners should be incorporated into the treatment of insomnia, reflecting seminal works that have demonstrated concordance in partners’ sleep habits.

Summary

This review of new developments in sleep health demonstrate robust gender differences in sleep duration and insomnia [23, 25, 65, 67]. Importantly, individual, interpersonal, and social determinants of sleep health emphasize the importance of investigating these gender differences using a socio-ecological framework [1••, 9••]. For example, while much of the past literature has indicated that women obtain more sleep than men [26•], new findings suggest that the opposite may be true in countries where women typically take on more housework or child-rearing responsibilities [34, 35]. Similarly, insomnia is most commonly diagnosed in women [65, 67], and this disparity is augmented by marginalized identities [76,77,78,79,80]. Age also provides important context for gender differences in sleep duration and insomnia, with the transition to adolescence [66], child-rearing years [27, 28], and menopause [68] representing vulnerable periods for women due to biological (e.g., hormonal, neurological) and socioecological (e.g., interpersonal problems, division of labor) factors.

Co-sleeping with a romantic partner may benefit some aspects of sleep [37•, 38,39,40, 43] while interfering with others. Couples are particularly vulnerable to experiencing interruptions to their sleep if at least one partner has a sleep disorder [90••]. Thus, the relative benefits of having a co-partner should be considered in the context of sleep disorders. Nevertheless, because of recent work on couples’ sleep, ongoing clinical trials [92, 101] are incorporating partners into their treatment paradigm, not only to improve patient sleep but also to improve partner sleep.

Limitations and Future Directions

This review focused on two sleep domains, sleep duration and insomnia, that have high public relevance and specific, behaviorally modifiable targets. Sleep quality was not discussed, but it also has high public health relevance. Indeed, much of public health research focuses on this parameter because it can be assessed with a single question and has high predictive utility [102]. Sleep quality is associated with insomnia, insufficient sleep, and other sleep disorders [54, 102, 103]. Future research that will benefit from large-scale, population studies will want to consider this generalizable assessment. In contrast, areas that need greater specificity for identifying targets will want to consider more nuanced assessments (e.g., sleep duration, diagnostic interviews). For example, couples research will benefit from both large-scale assessments of couples’ sleep and controlled studies that can parse out minute-to-minute changes based on dyadic patterns.

Findings on disparities in the amount of sleep needed to feel rested highlight the importance of incorporating multidimensional assessments of sleep [24, 36•], because factors other than duration (e.g., sleep timing and efficiency) can affect feeling rested upon awakening. The RU SATED questionnaire is a recent and innovative six-item measure of global sleep health [3]. Such global measures, and assessments of sleep health, align with proposed paradigm shifts in the field that align with overall well-being rather than focusing on individual deficits (e.g., insufficient sleep, poor sleep quality) [1••, 3]. In clinical settings, RU SATED can promote sleep health discussions with patients, as demonstrated by a recent pilot sleep health promotion study that provided tailored sleep health recommendations using RU SATED as a framework [104]. Moreover, conceptualizations of sleep health include individual, social, and environmental demands that may impact sleep [3]. Thus, using global measures of sleep health to assess sleep outcomes can bridge the gap between our understanding of sleep at an individual level and sleep in the larger socio-ecological context.

Emerging research on gender-based disparities in sleep duration and insomnia consistently highlights social and societal influences (e.g., social roles and norms, societal support). Increased identification and attention to broader societal contextual factors will clarify how intersecting socio-ecological identities may confer risk for poor sleep health [1••]. In particular, it is important for future research to address disparities in insomnia diagnoses among sexual and gender minority populations, considering the finding that they are twice as likely to be diagnosed with insomnia as their cisgender counterparts [79]. Similarly, socio-demographic and racial disparities increase the risk for poor sleep health, particularly in rural communities [105,106,107], but socio-economic status and ethno-racial diversity are rarely accounted for in sleep research [107]. Furthermore, large-scale studies could provide a more nuanced understanding of sleep across the lifespan by including parity (number of children) in analyses of young and middle adulthood, which may impact sleep and related health outcomes differently across gender and culture [73, 108,109,110,111,112].

To that end, while research has highlighted important dyadic processes that underlie domains of sleep health, much of this literature reflects cis-gendered, white, heterosexual couples [42]. It is important to understand dyadic processes of sleep in couples of all genders, particularly in light of very recent findings that women with same-sex partners feel less rested after getting less than 7 h of sleep compared to women with different-sex partners [36•]. Similarly, more research is needed to understand how these processes replicate in other ethnic groups. Notably, African Americans have increased risk for poorer sleep quality and insufficient sleep and the related poor health outcomes [113,114,115], such as obesity [116], type 2 diabetes [117], and higher levels of inflammation and preterm birth [118]. Learning more about dyadic sleep processes in other ethnic groups will help inform treatment options for those at higher risk of poor sleep outcomes.

Moreover, continuing to use dyadic approaches to sleep will inform specific ways in which the close environment influences sleep. Recent work on covariation (e.g., sleep duration covaries in couples; 42) and sleep concordance (e.g., synchrony in sleep/wake times in couples; 90) are two such examples that integrate established relationship theory and sleep health behaviors at the couple level [119]. Given intersectional influences on sleep at the individual level, it will be important to consider couples’ sleep in the context of other societal influences. For example, low SES is linked to shorter sleep at the couple level [48]. Improving sleep at the public health level will entail modifications across family, organizational, and policy domains [1••].

Conclusion

Recent developments in inadequate sleep and insomnia using a socio-ecological framework were reviewed. Findings affirm the importance of the social context when examining individual sleep. In particular, gender disparities in sleep duration are influenced by age and gender role expectations. Individual-level factors, such as anxiety, and larger socio-ecological factors, such as socio-economic status, influence sleep at the couple level. Advances in sleep equity will likely need to consider the multiple and intersectional influences on sleep. As such, future research will benefit from clarifying associations within and among individual, social, and societal domains.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

•• Hale L, Troxel W, Buysse DJ. Sleep health: an opportunity for public health to address health equity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2020;41:81. This article outlines individual, social, and contextual determinants of sleep health using a socioecological framework.

Yun S, Jo S. Understanding insomnia as systemic disease. Yeungnam Univ J Med. 2021;38:267–74.

Buysse DJ. Sleep health: can we define it? Does it matter? Sleep. 2014;37:9–17.

•• Appleton SL, Melaku YA, Reynolds AC, Gill TK, de Batlle J, Adams RJ. Multidimensional sleep health is associated with mental well-being in Australian adults. J Sleep Res. 2022;31: e13477. This community-based study demonstrates that global assessments of sleep health predict mental health, such that individuals with better sleep health report better mental health outcomes.

Dalmases M, Benítez I, Sapiña-Beltran E, et al. Impact of sleep health on self-perceived health status. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1–7.

Barnes CM, Drake CL. Prioritizing sleep health: public health policy recommendations. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10:733–7.

Espie CA. The ‘5 principles’ of good sleep health. J Sleep Res. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13502.

Mead MP, Irish LA. Application of health behaviour theory to sleep health improvement. J Sleep Res. 2020;29:e12950.

•• Grandner MA. Social-ecological model of sleep health. In: Sleep heal. Elsevier; 2019. p. 45–53. This chapter defines the socioecological model of sleep health.

Krishnan V, Collop NA. Gender differences in sleep disorders. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2006;12:383–9.

Krueger PM, Friedman EM. Sleep duration in the United States: a cross-sectional population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:1052–63.

Luckhaupt SE, Tak SW, Calvert GM. The prevalence of short sleep duration by industry and occupation in the National Health Interview Survey. Sleep. 2010;33:149–59.

Knutson KL, Van Cauter E, Rathouz PJ, DeLeire T, Lauderdale DS. Trends in the prevalence of short sleepers in the USA: 1975–2006. Sleep. 2010;33:37–45.

Nakata A. Investigating the associations between work hours, sleep status, and self-reported health among full-time employees. Int J Public Health. 2011;57:403–11.

Lippman S, Gardener H, Rundek T, Seixas A, Elkind MSV, Sacco RL, Wright CB, Ramos AR. Short sleep is associated with more depressive symptoms in a multi-ethnic cohort of older adults. Sleep Med. 2017;40:58–62.

Cappuccio FP, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Quantity and quality of sleep and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:414–20.

Cappuccio FP, Cooper D, D’elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep duration predicts cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1484–92.

Knutson KL. Sleep duration and cardiometabolic risk: a review of the epidemiologic evidence. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;24:731–43.

Cappuccio FP, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep. 2010;33:585–92.

Grandner MA, Hale L, Moore M, Patel NP. Mortality associated with short sleep duration: the evidence, the possible mechanisms, and the future. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14:191–203.

Kripke DF, Garfinkel L, Wingard DL, Klauber MR, Marler MR. Mortality associated with sleep duration and insomnia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:131–6.

Yang X, Chen H, Li S, Pan L, Jia C. Association of sleep duration with the morbidity and mortality of coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Hear Lung Circ. 2015;24:1180–90.

Khubchandani J, Price JH. Short sleep duration in working American adults, 2010–2018. J Community Health. 2020;45:219–27.

Tonetti L, Fabbri M, Natale V. Sex difference in sleep-time preference and sleep need: A cross-sectional survey among Italian pre-adolescents, adolescents, and adults. Chronobiol Int. 2008;25:745–59.

Li L, Nakamura T, Hayano J, Yamamoto Y. Age and gender differences in objective sleep properties using large-scale body acceleration data in a Japanese population. Sci Reports. 2021;111(11):1–11.

• Jonasdottir SS, Minor K, Lehmann S. Gender differences in nighttime sleep patterns and variability across the adult lifespan: a global-scale wearables study. Sleep. 2021;44:1–16. This global study of behaviorally assessed sleep duration suggests that men sleep longer than women, but women experience more nighttime awakenings, particularly around early-mid adulthood.

Mallampalli MP, Carter CL. Exploring sex and gender differences in sleep health: A society for women’s health research report. J Womens Health. 2014;23(7):553–62. https://home.liebertpub.com/jwh. Accessed 20 Jul 2022.

Pengo MF, Won CH, Bourjeily G. Sleep in women across the life span. Chest. 2018;154:196–206.

Thurston RC, Santoro N, Matthews KA. Are vasomotor symptoms associated with sleep characteristics among symptomatic midlife women? Comparisons of self-report and objective measures. Menopause. 2012;19:742.

Ohayon MM. Interactions between sleep normative data and sociocultural characteristics in the elderly. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:479–86.

Ishigooka J, Suzuki M, Isawa S, Muraoka H, Murasaki M, Okawa M. Epidemiological study on sleep habits and insomnia of new outpatients visiting general hospitals in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1999;53:515–22.

Kuula L, Gradisar M, Martinmäki K, Richardson C, Bonnar D, Bartel K, Lang C, Leinonen L, Pesonen AK. Using big data to explore worldwide trends in objective sleep in the transition to adulthood. Sleep Med. 2019;62:69–76.

Reyner A, Horne JA. Gender- and age-related differences in sleep determined by home-recorded sleep logs and actimetry from 400 adults. Sleep. 1995;18:127–34.

Tsuya NO, Bumpass LL, Choe MK, Rindfuss RR. Employment and household tasks of Japanese couples, 1994–2009. Demogr Res. 2012;27:705–18.

Baxter J, Hewitt B, Haynes M. Life course transitions and housework: marriage, parenthood, and time on housework. J Marriage Fam. 2008;70:259–72.

• Martin-Storey A, Prickett KC, Crosnoe R. Disparities in sleep duration and restedness among same- and different-sex couples: findings from the American Time Use Survey. Sleep. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsy090. This study highlights sexuality-based disparities in feeling rested.

• Andre CJ, Lovallo V, Spencer RMC. The effects of bed sharing on sleep: From partners to pets. Sleep Heal. 2021;7:314–23. This review reports that bed-sharing with a romantic partner is often associated with increased subjective sleep quality and sleep duration, though gender differences might exist.

Dittami J, Keckeis M, Machatschke I, Katina S, Zeitlhofer J, Kloesch G. Sex differences in the reactions to sleeping in pairs versus sleeping alone in humans. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2007;5:271–6.

Pankhurst FP, Horne JA. The influence of bed partners on movement during sleep. Sleep. 1994;17:308–15.

Spiegelhalder K, Regen W, Siemon F, Kyle SD, Baglioni C, Feige B, Nissen C, Riemann D. Your place or mine? Does the sleep location matter in young couples? Behav Sleep Med. 2015;15:87–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2015.1083024.

• Kim Y, Ramos AR, Carver CS, et al. Marital status and gender associated with sleep health among Hispanics/Latinos in the US: results from HCHS/SOL and Sueño ancillary studies. Behav Sleep Med. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2021.1953499/SUPPL_FILE/HBSM_A_1953499_SM7790.DOCX. This study of Hispanic/Latino adults demonstrates that being married or living with a partner predicts better sleep health, particularly among women.

Troxel WM, Robles TF, Hall M, Buysse DJ. Marital quality and the marital bed: examining the covariation between relationship quality and sleep. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11:389–404.

Drews HJ, Wallot S, Brysch P, Berger-Johannsen H, Weinhold SL, Mitkidis P, Baier PC, Lechinger J, Roepstorff A, Göder R. Bed-sharing in couples is associated with increased and stabilized REM sleep and sleep-stage synchronization. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:583.

Della Monica C, Johnsen S, Atzori G, Groeger JA, Dijk DJ. Rapid eye movement sleep, sleep continuity and slow wave sleep as predictors of cognition, mood, and subjective sleep quality in healthy men and women, aged 20–84 years. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:255.

Meyler D, Stimpson JP, Peek MK. Health concordance within couples: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:2297–310.

Lee S, Martire LM, Damaske SA, Mogle JA, Zhaoyang R, Almeida DM, Buxton OM. Covariation in couples’ nightly sleep and gender differences. Sleep Heal. 2018;4:201–8.

Otto AK, Gonzalez BD, Heyman RE, Vadaparampil ST, Ellington L, Reblin M. Dyadic effects of distress on sleep duration in advanced cancer patients and spouse caregivers. Psychooncology. 2019;28:2358–64.

Saini EK, Keiley MK, Fuller-Rowell TE, Duke AM, El-Sheikh M. Socioeconomic status and sleep among couples. Behav Sleep Med. 2020;19:159–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2020.1721501.

Drake CL, Roehrs T, Roth T. Insomnia causes, consequences, and therapeutics: an overview. Depress Anxiety. 2003;18:163–76.

Puzino K, Amatrudo G, Sullivan A, Vgontzas AN, Fernandez-Mendoza J. Clinical significance and cut-off scores for the pre-sleep arousal scale in chronic insomnia disorder: a replication in a clinical sample. Behav Sleep Med. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2019.1669604.

Kolla BP, He JP, Mansukhani MP, Frye MA, Merikangas K. Excessive sleepiness and associated symptoms in the U.S. adult population: prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity. Sleep Heal. 2020;6:79–87.

• Sidani S, Guruge S, Fox M, Collins L. Gender differences in perpetuating factors, experience and management of chronic insomnia. J Gend Stud. 2019;28:402–13. This study identifies individual and social-level perpetuating factors that may contribute to the gender disparity in insomnia.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of Dsm-5 TM. Am Psychiatr Assoc. 2013: 992.

Morin CM, Benca R. Chronic insomnia. Lancet. 2012;379:1129–41.

Léger D, Bayon V. Societal costs of insomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14:379–89.

Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN, Lin HM, Vela-Bueno A, Kales A. Insomnia in Central Pennsylvania. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:589–92.

Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6:97–111.

Fernandez-Mendoza J, Vgontzas AN. Insomnia and its impact on physical and mental health. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15:1–8.

Vgontzas AN, Liao D, Bixler EO, Chrousos GP, Vela-Bueno A. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration is associated with a high risk for hypertension. Sleep. 2009;32:491–7.

Fernandez-Mendoza J, Vgontzas AN, Liao D, Shaffer ML, Vela-Bueno A, Basta M, Bixler EO. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration and incident hypertension: the Penn State cohort. Hypertension. 2012;60:929–35.

Vgontzas AN, Liao D, Pejovic S, Calhoun S, Karataraki M, Bixler EO. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration is associated with type 2 diabetes: a population-based study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1980–5.

Vgontzas AN, Liao D, Pejovic S, Calhoun S, Karataraki M, Basta M, Fernández-Mendoza J, Bixler EO. Insomnia with short sleep duration and mortality: the Penn State cohort. Sleep. 2010;33:1159–64.

• Bertisch SM, Reid M, Lutsey PL, Kaufman JD, McClelland R, Patel SR, Redline S. Gender differences in the association of insomnia symptoms and coronary artery calcification in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Sleep. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1093/SLEEP/ZSAB116. This paper finds a significant gender difference in risk for subclinical atherosclerotic disease associated with insomnia which illustrates the importance of considering insomnia as a systemic health problem.

Riemann D, Nissen C, Palagini L, Otte A, Perlis ML, Spiegelhalder K. The neurobiology, investigation, and treatment of chronic insomnia. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:547–58.

Sivertsen B, Pallesen S, Friborg O, Nilsen KB, Bakke ØK, Goll JB, Hopstock LA. Sleep patterns and insomnia in a large population-based study of middle-aged and older adults: the Tromsø study 2015–2016. J Sleep Res. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/JSR.13095.

Zhang J, Chan NY, Lam SP, et al. Emergence of sex differences in insomnia symptoms in adolescents: a large-scale school-based study. Sleep. 2016;39:1563–70.

Zeng LN, Zong QQ, Yang Y, Zhang L, Xiang YF, Ng CH, Chen LG, Xiang YT. Gender difference in the prevalence of insomnia: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:1162.

Nguyen V, George T, Brewster GS. Insomnia in older adults. Curr Geriatr Reports. 2019;84(8):271–90.

Meers J, Stout-Aguilar J, Nowakowski S. Sex differences in sleep health. Sleep Heal. 2019: 21–29

Swanson LM, Kalmbach DA, Raglan GB, O’Brien LM. Perinatal insomnia and mental health: a review of recent literature. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22:1–9.

Van Someren EJW. Brain mechanisms of insomnia: new perspectives on causes and consequences. Physiol Rev. 2021;101:995–1046.

Rani R, Arokiasamy P, Selvamani Y, Sikarwar A. Gender differences in self-reported sleep problems among older adults in six middle-income countries: a cross-sectional study. J Women Aging. 2021;34(5):605–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952841.2021.1965425.

Wang H, Chen M, Xin T, Tang K. Number of children and the prevalence of later-life major depression and insomnia in women and men: findings from a cross-sectional study of 0.5 million Chinese adults. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12888-020-02681-2.

Orchard ER, Ward PGD, Sforazzini F, Storey E, Egan GF, Jamadar SD. Relationship between parenthood and cortical thickness in late adulthood. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0236031.

Fischer AR, Green SRM, Gunn HE. Social-ecological considerations for the sleep health of rural mothers. J Behav Med. 2021;44:507–18.

Polyné NC, Miller KE, Brownlow J, Gehrman PR. Insomnia: sex differences and age of onset in active duty Army soldiers. Sleep Heal. 2021;7:504.

Rosen RC, Cikesh B, Fang S, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder severity and insomnia-related sleep disturbances: longitudinal associations in a large, gender-balanced cohort of combat-exposed veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2019;32:936–45.

Bethea TN, Zhou ES, Schernhammer ES, Castro-Webb N, Cozier YC, Rosenberg L. Perceived racial discrimination and risk of insomnia among middle-aged and elderly Black women. Sleep. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/SLEEP/ZSZ208.

Hershner SD, Chervin RD. Causes and consequences of sleepiness among college students. Nat Sci Sleep. 2014;6:73.

Butler ES, McGlinchey E, Juster RP. Sexual and gender minority sleep: a narrative review and suggestions for future research. J Sleep Res. 2020;29:e12928.

López N, Gadsden V. Health inequities, social determinants, and intersectionality health disparities, inequity, and social determinants. 2016.

Jackson CL, Johnson DA. Sleep disparities in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic highlight the urgent need to address social determinants of health like the virus of racism. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020;16:1401–2.

Goldmann E, Hagen D, El KE, Owens M, Misra S, Thrul J. An examination of racial and ethnic disparities in mental health during the Covid-19 pandemic in the U.S. South J Affect Disord. 2021;295:471–8.

Alimoradi Z, Gozal D, Tsang HWH, Lin CY, Broström A, Ohayon MM, Pakpour AH. Gender-specific estimates of sleep problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sleep Res. 2022;31:e13432.

Zhou Y, Wang W, Sun Y, et al. The prevalence and risk factors of psychological disturbances of frontline medical staff in china under the COVID-19 epidemic: workload should be concerned. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:510–4.

• Tsou M-T. Gender differences in insomnia and role of work characteristics and family responsibilities among healthcare workers in Taiwanese tertiary hospitals. Front Psychiatry. 2022:883. This paper highlights the increased risk of insomnia among health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic and the mediating effects of work conditions and family responsibilities as social-ecological determinants of sleep health.

Salfi F, Lauriola M, Amicucci G, Corigliano D, Viselli L, Tempesta D, Ferrara M. Gender-related time course of sleep disturbances and psychological symptoms during the COVID-19 lockdown: a longitudinal study on the Italian population. Neurobiol Stress. 2020;13:100259.

Jahrami H, BaHammam AS, Bragazzi NL, Saif Z, Faris M, Vitiello MV. Sleep problems during the COVID-19 pandemic by population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17:299–313.

Richter K, Zimni M, Tomova I, et al. Insomnia associated with tinnitus and gender differences. Int J Environ Res Public Heal. 2021;18:3209.

•• Walters EM, Phillips AJK, Mellor A, Hamill K, Jenkins MM, Norton PJ, Baucom DH, Drummond SPA. Sleep and wake are shared and transmitted between individuals with insomnia and their bed-sharing partners. Sleep. 2020;43:1–12. This dyadic study of insomnia patients and their partners finds that both patients and partners are more susceptible to night time wakenings than are couples in which neither partner has insomnia.

Sedov I, Madsen JW, Goodman SH, Tomfohr-Madsen LM. Couples’ treatment preferences for insomnia experienced during pregnancy. Fam Syst Heal. 2019;37:46–55.

Mellor A, Hamill K, Jenkins MM, Baucom DH, Norton PJ, Drummond SPA. Partner-assisted cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia versus cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia: a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20:1–12.

Passarella S, Duong M-T. Diagnosis and treatment of insomnia. Am J Heal Pharm. 2008;65:927–34.

Bootzin RR, Epstein DR. Understanding and treating insomnia. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091516.

Chang HP, Chen YF, Du JK. Obstructive sleep apnea treatment in adults. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2020;36:7–12.

Benetó A, Gomez-Siurana E, Rubio-Sanchez P. Comorbidity between sleep apnea and insomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 2009;13:287–93.

Ong JC, Crisostomo MI. The more the merrier? Working towards multidisciplinary management of obstructive sleep apnea and comorbid insomnia. J Clin Psychol. 2013;69:1066–77.

Luyster FS. Impact of obstructive sleep apnea and its treatments on partners: a literature review. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13:467–77.

Luyster FS, Aloia MS, Buysse DJ, Dunbar-Jacob J, Martire LM, Sereika SM, Strollo PJ. A couples-oriented intervention for positive airway pressure therapy adherence: a pilot study of obstructive sleep apnea patients and their partners. Behav Sleep Med. 2019;17:561–72.

Luyster FS, Dunbar-Jacob J, Aloia MS, Martire LM, Buysse DJ, Strollo PJ. Patient and partner experiences with obstructive sleep apnea and CPAP treatment: a qualitative analysis. Behav Sleep Med. 2016;14:67–84.

Baron KG, Gilles A, Sundar KM, Baucom BRW, Duff K, Troxel W. Rationale and study protocol for We-PAP: a randomized pilot/feasibility trial of a couples-based intervention to promote PAP adherence and sleep health compared to an educational control. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2022;81(8):1–10.

Krystal AD, Edinger JD. Measuring sleep quality. Sleep Med. 2008;9:S10–7.

Benca RM. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic insomnia: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:332–43.

Levenson JC, Miller E, Hafer BL, Reidell MF, Buysse DJ, Franzen PL. Pilot study of a sleep health promotion program for college students. Sleep Heal. 2016;2:167–74.

Doering JJ, Szabo A, Goyal D, Babler E. Sleep quality and quantity in low-income postpartum women. MCN Am J Matern Nurs. 2017;42:166–72.

Mersky JP, Lee CTP, Gilbert RM, Goyal D. Prevalence and correlates of maternal and infant sleep problems in a low-income US sample. Matern Child Health J. 2020;24:196–203.

Grandner MA, Williams NJ, Knutson KL, Roberts D, Jean-Louis G. Sleep disparity, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic position. Sleep Med. 2016;18:7–18.

Fontein-Kuipers Y, Ausems M, Budé L, Van Limbeek E, De Vries R, Nieuwenhuijze M. Factors influencing maternal distress among Dutch women with a healthy pregnancy. Women Birth. 2015;28:e36–43.

Kang AW, Pearlstein TB, Sharkey KM. Changes in quality of life and sleep across the perinatal period in women with mood disorders. Qual Life Res. 2020;29:1767–74.

Orchard ER, Ward PGD, Chopra S, Storey E, Egan GF, Jamadar SD. Neuroprotective effects of motherhood on brain function in late life: a resting-state fMRI study. Cereb Cortex. 2021;31:1270–83.

Yang Y, Li W, Ma T-J, Zhang L, Hall BJ, Ungvari GS, Xiang Y-T. Prevalence of poor sleep quality in perinatal and postnatal women: a comprehensive meta-analysis of observational studies. Front Psychiatry. 2020: 161.

Young DR, Sidell MA, Grandner MA, Koebnick C, Troxel W. Dietary behaviors and poor sleep quality among young adult women: watch that sugary caffeine!. Sleep Heal. 2020;6:214–9.

Mezick EJ, Matthews KA, Hall M, Strollo PJ, Buysse DJ, Kamarck TW, Owens JF, Reis SE. Influence of race and socioeconomic status on sleep: Pittsburgh SleepSCORE project. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:410–6.

Patel NP, Grandner MA, Xie D, Branas CC, Gooneratne N. “Sleep disparity” in the population: poor sleep quality is strongly associated with poverty and ethnicity. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:1–11.

Williams NJ, Grandner MA, Wallace DM, Cuffee Y, Airhihenbuwa C, Okuyemi K, Ogedegbe G, Jean-Louis G. Social and behavioral predictors of insufficient sleep among African Americans and Caucasians. Sleep Med. 2016;18:103–7.

Bidulescu A, Din-Dzietham R, Coverson DL, Chen Z, Meng YX, Buxbaum SG, Gibbons GH, Welch VL. Interaction of sleep quality and psychosocial stress on obesity in African Americans: the Cardiovascular Health Epidemiology Study (CHES). BMC Public Health. 2010;10:581.

Knutson KL, Ryden AM, Mander BA, Van Cauter E. Role of sleep duration and quality in the risk and severity of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1768–74.

Blair LM, Porter K, Leblebicioglu B, Christian LM. Poor sleep quality and associated inflammation predict preterm birth: heightened risk among African Americans. Sleep. 2015;38:1259–67.

Gunn HE, Buysse DJ, Hasler BP, Begley A, Troxel WM. Sleep concordance in couples is associated with relationship characteristics. Sleep. 2015;38:933–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Sex and Gender Issues in Behavioral Health

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Decker, A.N., Fischer, A.R. & Gunn, H.E. Socio-Ecological Context of Sleep: Gender Differences and Couples’ Relationships as Exemplars. Curr Psychiatry Rep 24, 831–840 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-022-01393-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-022-01393-6